Abstract

Objective

In 2009, in a European survey, around a quarter of Europeans reported witnessing discrimination or harassment at their workplace. The parity committee from the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) designed a questionnaire survey to investigate forms of discrimination with respect to country, gender and ethnicity among medical professionals in hospitals and universities carrying out activities in the clinical microbiology (CM) and infectious diseases (ID) fields.

Design

The survey consisted of 61 questions divided into five areas (sociodemographic, professional census and environment, leadership and generic) and ran anonymously for nearly 3 months on the ESCMID website.

Subjects

European specialists in CM/ID.

Results

Overall, we included 1274 professionals. The majority of respondents (68%) stated that discrimination is present in medical science. A quarter of them reported personal experience with discrimination, mainly associated with gender and geographic region. Specialists from South-Western Europe experienced events at a much higher rate (37%) than other European regions. The proportion of women among full professor was on average 46% in CM and 26% in ID. Participation in high-level decision-making committees was significantly (>10 percentage points) different by gender and geographic origin. Yearly gross salary among CM/ID professionals was significantly different among European countries and by gender, within the same country. More than one-third of respondents (38%) stated that international societies in CM/ID have an imbalance as for committee member distribution and speakers at international conferences.

Conclusions

A quarter of CM/ID specialists experienced career and research discrimination in European hospitals and universities, mainly related to gender and geographic origin. Implementing proactive policies to tackle discrimination and improve representativeness and balance in career among CM/ID professionals in Europe is urgently needed.

Keywords: Discrimination, Career, European research, Infectious Diseases, Clinical Microbiology

Article summary.

Article focus

To investigate forms of discrimination with respect to country, gender and ethnicity among medical professionals in hospitals and universities carrying out activities in the clinical microbiology (CM) and infectious diseases (ID) fields.

Key messages

Gender differences in career levels for CM/ID specialists, both academic and non-academic, are significant. A quarter of CM/ID specialists experienced career and research discrimination in European hospitals and universities, mainly related to gender and geographic origin. Perception of discrimination on the basis of the geographical region of work is more widespread among Eastern and Southern Eastern European countries.

The burden of family care is disproportionally weighing on the shoulders of women. A huge gap divides men and women who are able to find a satisfactory balance between their work and family commitments.

Implementing proactive policies to tackle discrimination and improve representativeness and balance in career among CM/ID professionals in Europe is urgently needed.

Strengths and limitations of this study

First study performed at the European level specifically addressing the issue of discrimination in research and career among medical specialists.

Survey questionnaire designed to target an extremely varied set of potential respondents, including people of different gender, age, ethnicity, nationality, religion, sexual orientation, disciplinary specialisation, professional role and level.

Introduction

In 2000, the European Union adopted two very far-reaching laws to prohibit discrimination in the workplace based on racial or ethnic origin, religion, disability or sexual orientation.1 In 2009, a survey was conducted to track, at the European level, perceptions and opinions on this field.2 Overall, around a quarter of Europeans reported witnessing discrimination or harassment and 16% of them experiencing it within 1 year of the study. Discrimination on ethnic origin (61%) was perceived to be the most widespread grounds for discrimination, followed by discrimination based on age (58%), disability (53%) and gender (40%).2

Discrimination in the academic area is more difficult to analyse although many of the factors making scientific work settings unfriendly to women and under-represented minority groups are as common as in any other professional environment.3 4 In particular, in medical professional settings, discrimination is harder to address because medical science itself (as science in general) is considered to be objective and an area where personal success is only based on scientific merit.2 The common belief of the blindness of science with respect to any personal feature of scientists is the basis of the subtle, informal and hardly visible nature of its segregating mechanisms, which often goes unrecognised even by those who are negatively affected by them.5 When it comes to scientific professions, such as the medical one, it is also paramount to identify which are the real positions where leadership is expressed. In fact, these professions have undergone deep transformation in the last few decades, with new roles and new professional figures emerging, modification of hierarchies and career paths and changes in the relative values attributed to different skills and capacities.6 7

Over the last few years, many projects have been focused on characterising discrimination at work level in academic settings.6 8–11 Most important factors reported to contribute to the so-called ‘chilly climate’ for women and minority groups in science are the following: exclusion from informal networks and the existence of ‘hidden quotas’ for women's and minority groups’ presence in high-level positions,12 pay gap,6 access to resources for research and early-stage career development13 and evaluation of scientific merit.6 Gender discrimination, in particular, has been the focus of different European researches.6 8–10 14 The ‘She figures 2009’ project, a collaboration between the Scientific Culture and Gender Issues Unit of the Directorate-General for Research of the EU Commission and the Helsinki Group, showed that although the feminisation of the student population is one of the most striking aspects of the evolution of research over the last 30 years,15 in most European countries women's academic career remains markedly characterised by strong vertical segregation. Women represented 44% among university students and 18% among full professors. Even of more interest, of all countries observed, there was none where female wages were equal to men's, despite the almost universal existence of legislation to impose gender wage equality.6

More difficult is to look for an evidence of discrimination related to ethnic origin or belonging to any other under-represented minority in medical academic area. Most observations derive from the US Universities where, in 2008, African-Americans, Hispanics and Native Americans made up more than a third of the US population but only 8.7% of physicians and 15% of enrolment in medical schools.16

In order to verify if, and to what extent, forms of discrimination exist, the Parity Commission of the European Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (ESCMID) organised a pan-European questionnaire survey. This study was designed to explore different forms of discrimination with the main focus on gender, geographic origin and belonging to a minority among clinical microbiology (CM) and infectious diseases (ID) professionals working in European hospitals and universities.

Methods

A literature review was performed in order to define evidence and causes for discrimination in medical science and among CM/ID specialists. After assessing content validity, a pilot study including 10 participants from different European countries evaluated its acceptance and reproducibility, and results led to minor amendments to its format. The final survey (http://www.escmid.org/profession_career/parity_commission/parity_survey/) consisted of 61 questions divided in five areas (socio-demographic, professional census and environment, leadership and generic) and ran anonymously for nearly 3 months (from 17 March 17 to 7 June 2011) on the ESCMID website (see table 1). All ESCMID regular members, attendees of the 21st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID)/27th International Congress of Chemotherapy held in Milan, Italy and national/international ESCMID-affiliated societies’ members were invited to participate.

Table 1.

Questionnaire description

| Area | Number of questions | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic Qs. 1–15 | 15 | Qs. collecting basic information about demographic and sociographic variables. |

| Professional census Qs. 16–23 | 8 | Qs. collecting information about specialty, academic and professional achievement and employment status. |

| Professional environment Qs. 24–35 | 12 | Qs. collecting information on the respondent's experience/opinion about discrimination regarding three features of the professional environment: organisational cultures and behaviours; career support and work-life balance. |

| Leadership Qs. 36–56 | 21 | Qs. collecting information on the respondent's experience/opinion about discrimination regarding the attainment of leadership positions, distinguishing between discrimination affecting research practice, discrimination in the attainment of decision-making positions in research management and discrimination in scientific communication. |

| General Qs. 57–61 | 5 | Qs. collecting last impressions, comments and very general opinions. |

Qs.: questions.

Sample size calculation

Before administering the questionnaire a statistical description of the universe of reference (ie, European CM/ID specialists) according to geographic region and gender was accomplished based on information provided by the ESCMID. Since the type of sampling was of a non-probabilistic nature, it was not possible to exactly determine the statistical representativeness of the sample. However, sample size to attain a confidence level of 95% and a precision of ±5% was calculated as for a random sampling.17 A minimum of 400 respondents were set up to fulfil confidence level and precision. Using the simple random sampling we also calculated that with a sample overcoming 1000 units, with a confidence level of 95%, the precision of the esteem could be fixed, by analogy, at ±3%. Poststratification operations were also accomplished and respondents were weighted according to gender and geographical region of work. We consider a significant result only those showing gaps as wide as, at least, 10 percentage points (corresponding to a precision of ±5%).

Analysis of the main sources of discrimination

Determinants of discrimination were grouped into three main areas: professional life (including career issues and working environmental issues), discrimination process and work-life balance. As for the sources of discrimination, results were systematically processed by gender and geographical region. The 40 European countries were classified into five geographical regions: Western Europe (WE), Northern Europe (NE), Eastern Europe (EE), South-WE (SWE) and South-EE (SEE), according to the standard ESCMID criteria (see online supplementary annex 1). To assess salary differences, each respondent was asked to declare his/her gross-income level in Euros compared to six predefined income-classes in the questionnaire: <25 000 EUR; 25 000–44 999 EUR; 45 000–64 999 EUR; 65 000–94 999 EUR; >125 000 EUR.

To simplify presentation of the survey's results, three indexes were built (see table 2): Professional Achievement Index (PAI), Work-Life Balance Index (WLBI) and Gender Discrimination Perception Index (GDPI). To define each index a 3-step procedure was applied: selecting and weighing indicators, assembling the index for each respondent and creating aggregates of respondents based on the index (low/medium/high).

Table 2.

Definition of indexes according to indicators

| Acronym | Index | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| PAI | Professional Achievement Index | Peer-reviewed articles published in career |

| Funding received for research as principal investigator (2008/2010) | ||

| Membership in professional boards and committees | ||

| WLBI | Work-Life Balance Index | Responsibility for household duties |

| Having the number of children desired | ||

| Having/having not to discontinue career opportunities | ||

| Caring for an elderly or an ill parent or relative | ||

| GDPI | Gender Discrimination Perception Index | Reporting gender discrimination events |

| Perception of gender inequality in international societies | ||

| Perception of low representativeness, as for gender, of speakers at international conferences | ||

| Belief that gender impacts on career's opportunities |

Results

Overall, 1566 individuals participated in the survey. Among them, 1274 working in European countries at the time of the study were included in the analysis. Respondents’ distribution by gender, geographical region and age is shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Main epidemiological characteristics of 1274 participants, by gender

| Females N=784 | % | Males N=490 | % | Total | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region* Western Europe | 244 | 31.1 | 195 | 39.8 | 439 | 35.5 |

| Northern Europe | 96 | 12.2 | 61 | 12.4 | 157 | 12.3 |

| Eastern Europe | 127 | 16.2 | 49 | 10.0 | 176 | 13.8 |

| South-Western Europe | 137 | 17.5 | 79 | 16.2 | 216 | 17.0 |

| South-Eastern Europe | 180 | 23.0 | 106 | 21.6 | 286 | 22.4 |

| Year of age <35 | 251 | 32.0 | 102 | 20.8 | 353 | 27.7 |

| 35–49 | 331 | 42.2 | 217 | 44.3 | 548 | 43.0 |

| 50–64 | 189 | 24.1 | 155 | 31.6 | 344 | 27.0 |

| >65 | 13 | 1.7 | 16 | 3.3 | 29 | 2.3 |

| Specialty clinical microbiology | 384 | 48.9 | 216 | 44.1 | 600 | 47.0 |

| Infectious diseases | 263 | 30.9 | 227 | 46.3 | 539 | 42.3 |

*According to the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases classification of European regions (see online supplementary annex 1).

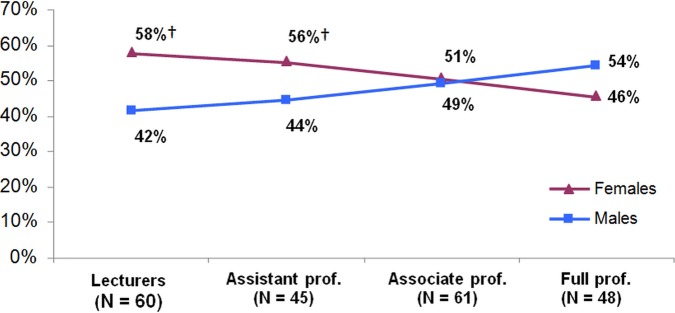

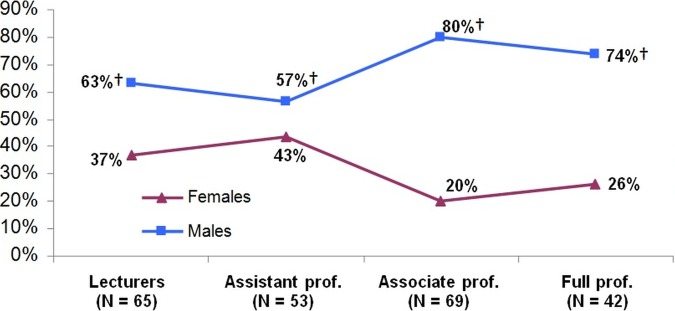

Table 4 illustrates the main professional achievement reached by 1274 respondents. Half of the interviewed individuals (51%) reported to be involved in an academic career. Overall, a clear imbalance in the number of women in the highest level of academic career was detected. Women accounted on average for 36% of full professorship in CM/ID. However, the difference is significantly more evident for ID than CM professionals (26% vs 46%; see figures 1 and 2). Women are even more under-represented in boards and committees with more than 20 percentage points dividing males from females (see table 4). The most striking difference was observed for participation in editorial boards (34% of females vs 66% of men). The presence in high-level decision-making bodies is also strongly influenced by geographic regions. Highest participation in expert panels is observed in professionals from NE (45%) and lowest in those from EE (26%; see online supplementary annex 2).

Table 4.

Main professional achievement of respondents, by gender

| Females | % | Males | % | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional level (N=1008) Head of division | 82 | 37.1 | 139 | 62.9* | 221 |

| Head of ward | 109 | 48.2 | 117 | 51.8 | 226 |

| Consultant | 156 | 44.3 | 196 | 55.7 | 352 |

| University career (N=649) Full professors | 37 | 36.3 | 65 | 63.7* | 102 |

| Associate professors | 48 | 34.8 | 90 | 65.2* | 138 |

| Assistant professors | 59 | 52.7 | 53 | 47.3 | 112 |

| Lecturers | 72 | 47.7 | 79 | 52.3 | 151 |

| Memberships (N=1274) Expert panels | 169 | 35.0 | 314 | 65.0* | 483 |

| Project evaluation committees | 164 | 38.6 | 261 | 61.4* | 425 |

| Program committees | 133 | 37.7 | 220 | 62.3* | 353 |

| Advisory boards | 122 | 34.1 | 236 | 65.9* | 358 |

| Recruitment committees | 106 | 37.9 | 174 | 62.1* | 280 |

| Editorial boards | 100 | 34.0 | 194 | 66.0* | 294 |

| Publications in peer-reviewed journals (N=1188) >200 | 4 | 14.3 | 24 | 85.7* | 28 |

| 101–200 | 25 | 33.3 | 50 | 66.7* | 75 |

| 51–100 | 43 | 36.1 | 76 | 63.9* | 119 |

| 11–50 | 160 | 42.9 | 213 | 57.1 | 373 |

| <=10 | 356 | 60.0* | 237 | 40.0 | 593 |

*Significant results: 10 percentage points difference (corresponding to a precision of ±5%).

Figure 1.

Proportion of 214 clinical microbiology professionals in different academic grades stratified by gender.

†Significant results: 10 percentage points difference (corresponding to a precision of ±5%); prof.: professor.

Figure 2.

Proportion of 229 infectious diseases professionals in different academic grades stratified by gender.

†Significant results: 10 percentage points difference (corresponding to a precision of ±5%); prof.: professor.

The number of publications in peer-reviewed journals, considered as the most traditional measure of scientific authority, shows clear gender differences (see table 4) and less evident regional differences (data not shown). Interestingly, a similar percentage of men and women report their name not being mentioned as first author when they were the ones conceiving the scientific publication and making the greater contribution to it (41% of men vs 37% of women). Age discrimination stands out as the most recurrent explanation given by 22% of respondents.

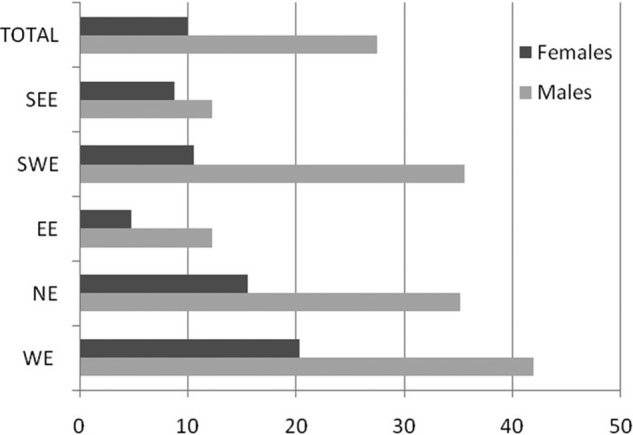

Yearly gross salary among ICM/ID professionals is significantly different among European countries. The highest (>10 percentage points) salary gap is observed among women from EE and SEE. After selecting high-income level only (>95 000 EUR/year), the percentage of inclusions ranges from 5% among professional females from EE to 42% of males in WE (see figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proportion of 235 clinical microbiology/infectious diseases professionals in top income levels (>95 000 euro/year) stratified by gender and geographic region.

The majority of respondents (68%) agreed that discrimination exists in scientific fields such as the medical science (see table 5). Respondents from SWE show the strongest commitment to gender issues while those from WE and NE are in an intermediate position and those from EE and SEE less agree on the presence of discrimination among ID/CM specialists (see table 6). A quarter of respondents (26%) reported witnessing or experiencing discrimination or harassment at their workplace (37% among women and 16% among men). As for regional differences, respondents from SWE countries report discrimination events at a much higher rate (37%) than average (26%), with the largest difference for gender while discrimination on the grounds of religion is more frequently denunciated from SEE countries (8%; see table 5).

Table 5.

Proportion of CM/ID professionals declaring to have experienced or witnessed discrimination, by gender (N=1255)

| Females | %* | Males | %* | Total | %* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existence of discrimination† | 461 | 73.8 | 363 | 57.5 | 824 | 68 |

| At least one report | 230 | 36.8‡ | 101 | 16.1 | 331 | 26.5 |

| 1 Report | 175 | 28.0 | 75 | 12.0 | 250 | 20.1 |

| 2 Reports | 34 | 5.4 | 14 | 2.2 | 48 | 3.8 |

| > 2 Reports | 21 | 3.4 | 12 | 1.9 | 33 | 2.6 |

| Gender | 186 | 29.8‡ | 39 | 6.2 | 225 | 18.0 |

| Ethnicity | 32 | 5.1 | 20 | 3.2 | 52 | 4.2 |

| Nationality | 57 | 9.1 | 43 | 6.9 | 100 | 8.0 |

| Religious background | 27 | 4.3 | 19 | 3.0 | 46 | 3.7 |

| Sexual orientation | 19 | 3.0 | 21 | 3.4 | 40 | 3.2 |

*Percentages refer to the total number of people interviewed (1251).

†The respondent was asked her/his opinion on the presence of discrimination in medical science (yes/no).

‡Significant results: 10 percentage points difference (corresponding to a precision of ±5%).

CM: clinical microbiology; ID: infectious diseases.

Table 6.

Proportion of CM/ID professionals declaring to have experienced or witnessed discrimination, by geographic region

| WE N=578% | NE N=110% | EE N=135% | SWE N=255% | SEE N=173% | Total N=1251% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least one rep. | 27.3 | 14.5† | 17.8 | 37.1† | 21.4 | 26.5 |

| 1 Report | 21.6 | 10.0 | 15.6 | 27.2 | 15.1 | 20.1 |

| 2 Reports | 3.5 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 3.8 |

| >R reports | 2.2 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 2.6 |

| Gender | 17.5 | 12.8 | 12.2 | 29.6* | 10.1 | 18.0 |

| Ethnicity | 4.2 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 6.6 | 4.1 | 4.2 |

| Nationality | 7.8 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 11.2 | 8.1 | 8.0 |

| Religious background | 3.9 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 8.1 | 3.7 |

| Sexual orientation | 3.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 6.2 | 1.9 | 3.2 |

*Significant results: 10 percentage points difference (corresponding to a precision of ±5%); N=number.

CM, clinical microbiology; EE, Eastern Europe; ID, infectious diseases; NE, Northern Europe; SEE, South-EE; SWE, South-WE; WE, Western Europe.

More than one-third (37%) of respondents believe that CM/ID international societies have discrimination problems, mainly related to country misbalance (28%) and gender inequality (15%). More than 20% believe that the most important international CM/ID conferences (ECCMID and Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy) are not balanced mainly for a speaker's geographic region of origin (57%). The majority of respondents (72%) believe that international societies should play a major role in helping universities and hospitals in addressing career-related issues and related discriminatory events (box 1).

Box 1. Definitions of terms used in the article.

Meritocracy: It is a system of government or other administration (such as business administration) wherein appointments and responsibilities are objectively assigned to individuals based upon their ‘merits’, namely intelligence, credentials and education, determined through evaluations or examinations.

Discrimination: The treatment or consideration of, or making a distinction in favour of or against, a person based on the group, class or category to which that person belongs rather than on individual merit. It involves intentional behaviours towards such groups, for instance, formally or informally excluding or restricting members of one group from opportunities that are available to another group.

Inequality: The observable and measurable effects of discriminatory practices and habits, resulting in differential conditions of professionals within scientific and managerial careers.

Minorities: Minorities among healthcare workers were defined as those discriminated in their professional career and/or under-represented in scientific societies because of gender, age, sexual orientation, racial, regional, religious and/or political reasons without consideration of their personal achievements.

The number of children reported might be considered as an indirect hint of the greater difficulty of women in CM/ID fields in reconciling work and family life. More than 20 percentage points divided the number of women and men who have two or more children (35% of women vs 56% of men). Analysis of geographical distribution shows that there are relevant differences among European regions having two or more children: NE 69%, WE 47%, SWE 40%, EE 39% and SE 38%. Considering different age classes, people under 35 years strongly regret having to wait longer than desired for having a child. People in the age class 35–49 years, on the other hand, more often report having less children than desired, or not at all, because of work commitments (36% of women and 19% of men).

As expected, household duties are strongly influenced by gender. Women from SWE largely outnumber men as the ones who take up the greater part (75%) of household duties: 68% of women vs 7% of men. After stratifying for age, while women under age 35 performing 100% of domestic chores are 29% and then the percentage slight decreases over the years, the trend for males is completely different. They perform all domestic duties until they presumably live alone (29% under age 35), then the figure suddenly drops by 20 percentage points and remains very low for all other age classes.

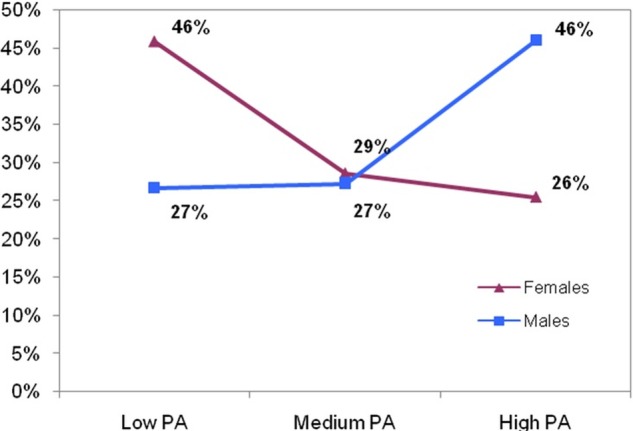

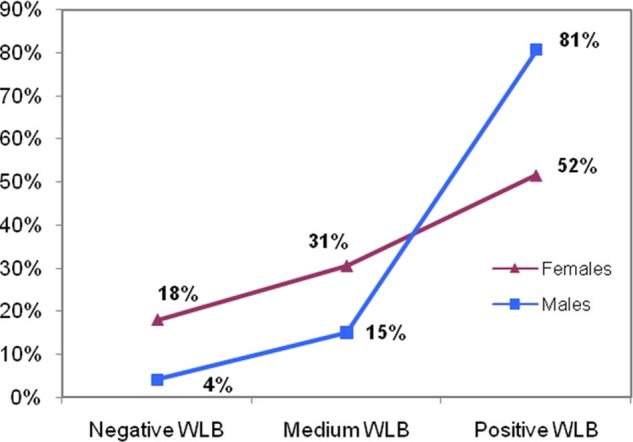

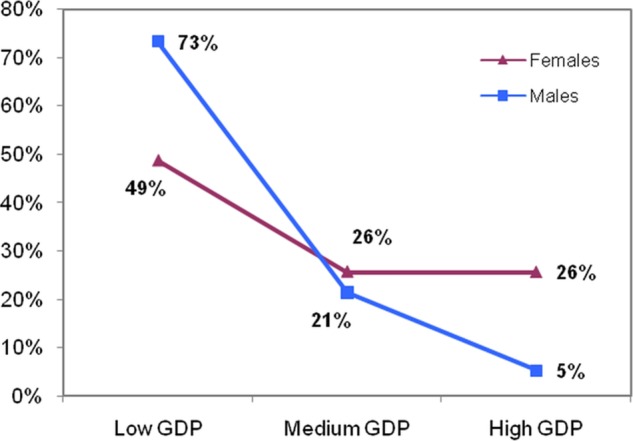

The distribution of indexes summarises the major area of discrimination. The PAI distribution adjusted by age is shown in figure 4. More than 20 points divide high professional achievements according to gender (46% of men vs 26% of women) while regional differences are minimal (data not shown). The WLBI confirms the same distribution (see figure 5) with more than 30 percentage points of difference (81% of men vs 52% of women). Perception of gender discrimination according to the GDPI is presented in figure 6 with a significant difference between females and males (26% vs 5%).

Figure 4.

Professional achievements according to PAI stratified by gender.

PAI: Professional Achievement Index. Each indicator was evaluated on a trichotomous ordinal scale (low/medium/high presence). Each mode was attributed a numerical value between 0 and 1. The results obtained for each individual indicator were then added. To make the results of the different indexes homogeneous, the value scale of each index has been equalised at a 0–10 range. For each index a threshold system has been set up, so to place each individual within a ‘low/medium/high’ trichotomous scale with respect to a given profile (for instance: ‘medium professional achievement’). See table 2 for indicators included in this index.

Figure 5.

Work-life balance according to WLBI stratified by gender.

WLBI: Work-Life Balance Index. Each indicator was evaluated on a trichotomous ordinal scale (low/medium/high presence). Each mode was attributed a numerical value between 0 and 1. The results obtained for each individual indicator were then added. To make the results of the different indexes homogeneous, the value scale of each index has been equalised at a 0–10 range. For each index a threshold system has been set up, so to place each individual within a ‘low/medium/high’ trichotomous scale with respect to a given profile (for instance: ‘positive work-life balance’). See table 2 for indicators included in this index.

Figure 6.

Perception of gender discrimination according to GDPI stratified by gender.

GPDI: Gender Discrimination Perception Index. Each indicator was evaluated on a trichotomous ordinal scale (low/medium/high presence). Each mode was attributed a numerical value between 0 and 1. The results obtained for each individual indicator were then added. To make the results of the different indexes homogeneous, the value scale of each index has been equalised at a 0–10 range. For each index a threshold system has been set up, so to place each individual within a ‘low/medium/high’ trichotomous scale with respect to a given profile (for instance: ‘low perception of gender discrimination’). See table 2 for indicators included in this index.

Discussion

Three main conclusions can be drawn from our survey. First, gender differences in career levels for CM/ID specialists, both academic and non-academical, are significant. If gender differences in achievement are measured through substantial indicators of scientific and professional success, such as scientific publications, research funding and participation in boards and committees, large gaps are still recorded between men and women and are consistent among professionals working in all European regions. Second, more than two-thirds of CM/ID professionals recognise the existence of discriminatory problems at their workplace. The perception of discrimination on the basis of the geographical region of work is more widespread among EE and SEE countries. Third, the burden of family care is disproportionally weighing on the shoulders of women. A huge gap divides men and women who are able to find a satisfactory balance between their work and family commitments. Even though there are important differences in women's situation in the different regions, the gap with men is always much wider in all regions, including NE countries (box 2).

Box 2. Why is discrimination so hard to acknowledge.

Difficult to recognise, since it is subtle, informal and generally embodied in well-established cultural, organisational and behavioural patterns.

Annoying to admit, since it jeopardises one's opinion about the fairness and quality of the environment s/he works in, which may be experienced by some as an aggression to their professional identity.

Somewhat depressing to admit, since it affects the self-esteem, self confidence and hopes of the potential victims of.

Often counterproductive to admit, since it puts the hard-won credibility of women and under-represented groups at risk in the working environment.

Our data clearly show the gap in professorship's distribution between men and women. The data resemble the ‘scissor phenomenon’, a graphical representation of the divergence of men and women as they adopt senior positions in academic research, associate professorships and full professorships over time. Previous studies showed that although the number of women entering the first grade of medical school outnumbered that one of men, they then suddenly, after PhD, are no longer found in positions of relevance in any universities across Europe.6 10 Among CM and ID professionals the difference in different academic grades stratified by gender is significantly more evident for ID than CM professionals (26% vs 46%). Wide differences were also observed according to geographic regions. There are many cultural, economic and organisational reasons behind the wide differences that do emerge for academic career among CM/ID specialists. It is worth noticing that the regions where the gender gap is smaller among full professors (NE, EE and SEE) are those where women outnumber men to a larger extent among CM professionals. In this field women enjoy a relatively less discriminating environment. However, it is important to underline that in many European countries, especially where microbiology is practising mainly as laboratory discipline and not as CM, the career path is less ‘appealing’ than other medical disciplines. This is not, however, the only variable having an impact, since situations are extremely varied. In daily ‘real’ university life we frequently hear that plausible ‘explanation’ from women not being represented at the same level of men at highest academic career is that women are less interested in academic career since this is not feasible with family and in particular with children care. The fact that women publish less than men is usually used as a key supporting argument. However, previous studies documented that productivity is affected by a number of factors which are unrelated to scientific merit.15–21 Regional differences in publishing also suggest the existence of many determinants of scientific productivity. Professionals from WE and SWE are those with the highest rate of publications among CM/ID professionals. Creamer suggested that prolific publishers are disproportionately white males because the career paths, work assignments, research interests and access to resources conducive to frequent publishing are more characteristic of white men than of women and minorities.18 However, family responsibilities probably have less effect on women's publishing activity than work assignments and time. Finally, women's lower publishing rates may be a consequence of a ‘chilly climate’ in some academic departments. Women are more likely than men to be excluded and isolated from the types of professional and social networks that define the life of a department. As our survey shows, women and professionals from EE are less likely than men to receive visiting appointments and participate in high-level decision-making boards, activity that encourages the building of professional networks and contacts outside home institutions. In this sense, productivity appears as a function of one's position in the communication system in a discipline rather than personal scientific merits.

The analysis of gap salary related to gender and geographic regions is more difficult to analyse. A major limitation we encountered is related to the impossibility to adjust our results to national gross domestic product per capita corrected by local life costs. However, the pay gap between women and men is consistent within the same country in all European nations. Therefore, a need to implement proactive policies to tackle gender pay gap at the European level is crucial.

Our data show that the issue of inequality in medical science is strongly perceived by the majority of CM/ID professionals (68%). Differences can be recorded across geographical areas, although there is no region where consensus on the existence of discrimination falls below 66% of respondents, while if we only include those reporting substantial discrimination, we never fall below 50%. Even of more interest a quarter of respondents reported witnessing or experiencing discrimination at their workplace mainly related to gender and nationality. The analysis of the work-life balance also showed significant differences according to gender. However, it is noteworthy that a substantial part of respondents, regardless of the gender, regret having to wait longer than desired for having a child or having less children than desired, or not at all, because of work commitments.

Finally, the use of indexes that, including different questions’ results, was introduced to summarise and simplify main conclusions, further underlines that there is a dramatic difference among CM/ID specialists by gender regarding professional achievement, life satisfaction and perception of discrimination.

Strengths and weakness of study

This is the first study performed at the European level specifically addressing the issue of discrimination in research and career among medical specialists. Previous researchers analysed the issue mainly related to the scientific academic area and never specifically on the medical one. Since the importance of the researchers’ selection and career development in medicine and the consequential impact on European citizens’ health we do believe the definition of such a high level of perceived and actual career discrimination should be carefully evaluated by policymakers. Our study has many limitations. First of all, the ESCMID survey questionnaire was designed to target an extremely varied set of potential respondents, including people of different gender, age, ethnicity, nationality, religion, sexual orientation, disciplinary specialisation, professional role and level. It was obviously impossible, also considering it had to take the shortest time possible to be filled out, to adequately cover all aspects which would have deserved to be analysed if each of those qualities had to be taken in full consideration. It was also impossible to proceed with a reliable stratification according to more variables than gender and the geographic region of current employment.

Further research

Future researches should focus on some of the neglected issues, for instance targeting ethnicity, religion and sexual orientation in more details. To obtain a more accurate understanding of the CM/ID reality as concerns equality issues other methodological approaches and sources of information should be added, such as direct observation, focus groups and qualitative interviews. It is also important to underline the tendency of professionals (both genders) to see scientific societies more involved than their own institutes in coping with parity issues. In particular, respondents seem to particularly value the role of international societies could play, beyond scientific exchange, as professional networks with a major role in dealing with professional issues, including those related to the work environment, work-life balance and career. Specific studies on international medical societies and parity issues should be therefore promoted in order to better understand these dynamics and to identify the real demands professionals express to societies and to institutes when parity issues are at stakes.

Implications for clinicians and policymakers

We believe that the results of our survey will play a major role in stimulating CM and ID specialists, other international societies for different specialisations as well as media to press policymakers to evaluate the fairness of academic career at the national level. However, we are aware that a significant improvement in the current situation at hospital and university level for medical specialists can be reached only through more direct involvement of policymakers at the European level. Informal exclusion (‘hidden quotas’) of new and young scientists just for being women or coming from a discriminated geographic region will definitively limit research and therefore will impact on future health of the Europeans citizens. In many countries, laws to define recruitment in the academic area, ensuring equal opportunities for all scientists, regardless of gender and country of origin, need to be introduced. Our final common goal should be to move from science without meritocracy towards science only based on meritocracy in a very near future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Karin Werner and Judith Zimmerman (ESCMID administrative office) in providing additional data and their support of this work.

Footnotes

Contributors: ET had the idea of the research, contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafted the paper. MC and GC contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. MP, NB, EN and TK contributed to the conception of the study, interpretation of the data and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: ESCMID provided a grant for the statistical assistance.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Data sharing statement: Further summary data are available from the corresponding author at Evelina.Tacconelli@med.uni-tuebingen.de.

References

- 1. Directive 2000/43/EC of 29 June 2000 and Directive 2000/78/EC of 27 November 2000.

- 2. Discrimination in the EU in 2009. Fieldwork May–June 2009. Special Eurobarometer 317. [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Commission 2000 Science Policies in the European Union: Promoting Excellence through Mainstreaming Gender Equality. ETAN Report, Luxembourg [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santamaría A, Merino A, Viñas O, et al. Does medicine still show an unresolved discrimination against women? Experience in two European university hospitals. J Med Ethics 2009;35:104–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller EF. Reflections on gender and science. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Commission 2009, She Figures 2009 Statistics and Indicators on Gender Equality in Science, Brussels [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palomba R. Does gender matter in scientific leadership? In: Brouns M, Addis E, eds. OECD, Women in scientific careers. Unleashing the potential. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2006:121–5 [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Commission 2004. Luxembourg: Gender and Excellence in the Making. [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Commission 2007 Remuneration of Researchers in the Public and Private Sectors. Final report Brussels [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Commission 2008 Gender Equality Report. Framework Programme 6, EC, Brussels [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alcon A, Peña T, Arrizabalaga P. Women physician and health research. Med Clin 2012;138:343–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta N, Kemelgor C, Fuchs S, et al. Triple burden on women in science. A cross-cultural analysis. Curr Sci 2005;89:1382–6 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellemers N, Van Den Heuvel H, De Gilder D, et al. The underrepresentation of women in science. Differential commitment or the queen bee syndrome? Br J Soc Psychol 2004;43:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmer A. 2003. Women in European Universities. Final Report 2000–2003 of the Research and Training Network. http://www.women-eu.de (accessed 11 Jan 2012)

- 15.Aleixandre Benavente R, González-Alcaide G, Alonso-Arroyo A, et al. Valoración de la paridad en la autoría de los artículos publicados en la Revista Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica durante el quinquenio 2001–2005. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2007;25:619–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan LW, Mittman SL. The state of diversity in the health professions a century after Flexner. Acad Med 2010;85:246–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinauer LD, Ondeck KE. Gender and institutional affiliation as determinants of publishing in human communications research. Hum Commun Res 1999;25:548–68 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creamer EG. Assessing Faculty Publication Productivity: Issues of Equity, ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report 26(2), Graduate School of Education and Human Development, George Washington University, 1998

- 19.Long JS. Measures of sex differences in scientific productivity. Soc Forces 1992;71:159–78 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathews AL, Andersen K. A gender gap in publishing?. Political Sci Polit 2001;34:143–7 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider A. Why don't women publish as much as men? Some blame inequity in academe; others say quantity doesn't matter. The Chronicle of Higher Education 1998;11:A14 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.