Abstract

Objectives

Rock and pop fame is associated with risk taking, substance use and premature mortality. We examine relationships between fame and premature mortality and test how such relationships vary with type of performer (eg, solo or band member) and nationality and whether cause of death is linked with prefame (adverse childhood) experiences.

Design

A retrospective cohort analysis based on biographical data. An actuarial methodology compares postfame mortality to matched general populations. Cox survival and logistic regression techniques examine risk and protective factors for survival and links between adverse childhood experiences and cause of death, respectively.

Setting

North America and Europe.

Participants

1489 rock and pop stars reaching fame between 1956 and 2006.

Outcomes

Stars’ postfame mortality relative to age-, sex- and ethnicity-matched populations (USA and UK); variations in survival with performer type, and in cause of mortality with exposure to adverse childhood experiences.

Results

Rock/pop star mortality increases relative to the general population with time since fame. Increases are greater in North American stars and those with solo careers. Relative mortality begins to recover 25 years after fame in European but not North American stars. Those reaching fame from 1980 onwards have better survival rates. For deceased stars, cause of death was more likely to be substance use or risk-related in those with more adverse childhood experiences.

Conclusions

Relationships between fame and mortality vary with performers’ characteristics. Adverse experiences in early life may leave some predisposed to health-damaging behaviours, with fame and extreme wealth providing greater opportunities to engage in risk-taking. Millions of youths wish to emulate their icons. It is important they recognise that substance use and risk-taking may be rooted in childhood adversity rather than seeing them as symbols of success.

Keywords: Public Health, Epidemiology, Occupational & Industrial Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

Despite often considerable wealth, rock and pop stars suffer higher levels of mortality than demographically matched individuals in the general population.

Previous studies have not considered whether such mortality risks in stars vary with the characteristics of the performer or whether cause of death may be related to experiences predating fame.

We examine whether stars still suffer excess mortality compared to matched general populations, identify which demographic and performer-type characteristics of performers affect survival and measure associations between adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and cause of death.

Key messages

Mortality of rock and pop stars varies with demographics, nationality and other performer characteristics while cause of death is more likely to be risk related in those who have suffered ACEs.

Fame increases opportunities to indulge established risk behaviours such as substance abuse. However, such risk-taking may be rooted in earlier ACEs, the impact of which even unlimited wealth may not fully redress.

Stars are influential figures in the development and dissemination of youth culture. A better understanding of the underlying causes of risk-taking in performers may help deglamorise such behaviour and reduce its appeal to fans and would-be rock and pop stars.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Rock and pop stars represent a unique opportunity to examine a group sometimes with extreme wealth but often from poor or modest backgrounds.

Although stars are typically not accessible through traditional survey techniques considerable information is available on them through biographical publications, news and other media coverage.

The accuracy and completeness of data collated from media and biographical sources cannot be quantified. However, such limitations are unlikely to have generated the patterns identified in this study.

Introduction

Despite their small numbers, the behaviour and health of rock and pop stars receive extensive public exposure1 2 and arguably exert a disproportionate influence on population attitudes and behaviours.3–5 Within the rock and pop music industries, excessive alcohol use, recreational and prescription drug use and other risk-taking behaviours have been described as ubiquitous.6 International media coverage ensures that fans and the wider public are constantly informed of stars’ hedonistic displays and equally captures their consequences when behaviours become problematic and such individuals seek treatment.2 Media coverage of rock and pop stars’ deaths typically suggests elevated risks of mortality at young ages and even a fanciful, but unsubstantiated, peak in deaths at age 27 years (eg, Kurt Cobain, Amy Winehouse and Janis Joplin).7

Cursory examinations of rock and pop star deaths can fail to account for confounding demographics. For instance, the rock and pop star phenomenon is relatively new (largely from the 1950s) with deaths of such stars in older age only now emerging. Deaths that occur in stars’ later years may receive less coverage due to diminished media appeal or lower shock factor (eg, following a long battle with cancer). Moreover, deaths at younger ages routinely occur in developed countries even in the general public (eg, <25 years; 67 044 in the USA8 and 8126 in the UK9 in 2009). These deaths are also disproportionately associated with substance use with, for instance, around one in four deaths in 16-year-olds to 24-year-olds in England attributable to alcohol.10 Despite such confounders, epidemiological analyses of stars reaching fame up to the beginning of this millennium showed they suffer disproportionate mortality even when controlled for age, sex, ethnicity and nationality.11

The past decade has seen unprecedented changes in global communications, increasing media exposure (eg, celebrity magazines and gossip websites) and other coverage (eg, social networking) of celebrities12 as well as the extension and resuscitation of older stars’ careers through band reunions and nostalgia tours (eg, Take That13 and Stone Roses14). Furthermore, substantive numbers of stars and former stars over 60 years of age are only now becoming available for study. Critically however, studies in the general population are establishing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as major factors influencing substance use and health outcomes in later life.15 16 Although some rock and pop stars may seek fame as a mechanism to escape deprived and abusive childhoods17 such factors are rarely considered when examining their premature mortality. Instead, substance use and risk-taking in stars are largely discussed in terms of hedonism, music industry culture, responses to the pressures of fame or even part of the creative process.18

Here, we examine the impact of fame on mortality in North American and European rock and pop stars. We update a previous epidemiological analysis11 to include more recent stars (reaching fame between 2000 and 2006) and incorporate larger numbers of older and experformers. We examine risk and protective factors for mortality in stars. For the first time we also explore the relative contributions of ACEs and other performer characteristics to cause of premature death among rock and pop stars.

Methods

Selecting rock and pop stars

With no internationally agreed definition of what constitutes a rock or pop star we used large, established music polls to identify which individuals to include. An international poll of over 200 000 fans, experts and critics identified the all-time top 1000 albums up to the year 1999.19 This poll was not repeated in subsequent years but an online poll-of-polls now combines >5000 album charts from experts, fans and critics and provides annual rankings of the best albums (http://www.besteveralbums.com). Along with the 1000 albums up to 1999, the top 30 albums each year from 2000 to 2006 were included in this study (total n=1210), with a minimum of 5 years fame considered necessary to calculate survival. Any solo performer or group member with an album in this list was included in the cohort (excluding compilation/soundtrack albums, n=11; table 1). Using and cross-referencing between key websites (eg, Wikipedia, BBC Music, Last FM, All Music and official band websites), biographies, and published anthologies, each individual's date of birth and survival status on 20 February 2012 was identified. Based on music classifications from http://www.allmusic.com, those from the mainstream categories of pop/rock, punk, rap, R&B (rhythm and blues), electronica and new age were included. Individuals from genres typically regarded as not being mainstream in both North America (NA) and Europe (EU) (country, blues, jazz, vocal, celtic, folk, bluegrass and spoken word) were removed. Those for whom date of birth or nationality was unknown were also excluded along with anyone not of European or North American nationality (table 1). Of the final sample (n=1489), 55.9% were from NA and 44.1% from EU. We did not distinguish different levels of fame among stars. However, they were classified as solo or band performers, with an individual considered a solo performer if they had a solo album in the study; regardless of whether this preceded or followed success as a band member (eg, Phil Collins and Genesis; Sting and The Police).

Table 1.

Sample selection: exclusions and inclusions

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Albums | 1210 | 100.0 |

| Excluded | ||

| Compilation albums | 2 | 0.2 |

| Soundtracks | 9 | 0.7 |

| Additional albums by performers already included* | 279 | 22.8 |

| Included | 923 | 76.3 |

| Individuals (from 923 albums) | 1714 | 100.0 |

| Excluded | ||

| Excluded genre† | 81 | 4.7 |

| Not from North America or Europe | 69 | 4.0 |

| Included | 1564 | 91.3 |

| Missing data | ||

| No nationality and date of birth | 25 | 1.6 |

| No nationality | 1 | 0.1 |

| No date of birth | 49 | 3.1 |

| Included | 1489 | 95.2 |

*Where additional albums included new band members such individuals were also included in the final data set.

†Country, blues, jazz, vocal, celtic, folk, bluegrass and spoken word.

Cause of death and ACEs

Date and cause of death were identified for the 137 deceased individuals. Causes of death were dichotomised into ‘substance use or risk-related deaths’ (drug or alcohol-related chronic disorder, overdose or accident and other risk-related causes that may or may not have been related to substance use, ie, suicide and violence) and ‘other’. For those who had died, ACEs were identified through the same online and published biographical sources. ACEs were taken from the WHO-standardised ACE questionnaire20 and here included suffering as a child: (1) physical abuse; (2) sexual abuse; (3) substantive verbal abuse; living with: (4) a depressed, mentally ill, suicidal or chronically ill person; (5) a substance-abusing household member; (6) a family with an incarcerated household member; (7) a separated family or (8) domestic violence. Data for ACEs in each individual's past were independently collected by two researchers (OS, KAH; concordance 97.5%) and conflicts resolved by MAB and KH.

Measuring point of fame

For an objective measure of age and date of fame, we used the earliest of date of first chart success (n=1012) or date of release of earliest album included in the study (n=477). Chart success was measured as the earliest of when an individual first appeared on an album in the Top 40 UK Official Chart (n=636) or Top 40 US Billboard 200 (n=239). For those without Top 40 albums, a Top 40 single (UK chart n=27; US Billboard Hot 100, n=1) was used and, for remaining performers, the earliest Top 40 album or single in a specialist US chart (Pop, n=87; Black, n=13; Heatseekers, n=9) was used. The earliest year of fame was 1956 for Elvis Presley and the latest was 2006 for 45 individuals including Lupe Fiasco, Regina Spektor and members from bands including Arctic Monkeys and Snow Patrol.

Calculating survival

Survival since becoming famous was calculated for comparison to expected survival based on general populations (matched to stars for sex, nationality, ethnicity, date of fame and age at fame). NA and EU stars were dominated by the USA (94.0%) and the UK (87.4%) nationalities, respectively, and therefore USA and UK national populations were used for comparisons. Analysis utilised the actuarial survival method (ie, age standardised relative survival).11 Individual performers were matched to corresponding annual survival probabilities experienced by average individuals (age, sex and ethnicity matched) in the general population in or near their year of fame. General population survival probabilities were taken from cohort life tables. For EU stars, we used the 2010-based UK historic cohort men and women life tables (1955–2010)21 with population denominators retro-adjusted using the 2001 UK census and subsequent migration studies. For NA, we calculated cohort tables from the USA decennial period life tables by using an offset transposition matrix.22 For years of fame from 1955 to 1964 we applied the 1959–1961 decennial tables, and so on. For the years since 2005, we applied the 2007 USA annual period life tables. Race-specific US tables were calculated separately for white and black men and women (in 1959–1961 decennial tables, `non-white' was used as black was not specified). In total, 14 112 sets of life tables were used to generate reference survival rates: UK men, UK women, US black men, US black women, US white men and US white women. Relative rock and pop star survival was calculated by expressing their survival as a percentage of the average of the corresponding survival probabilities from the matched reference populations. Age-standardised relative survival and 95% CIs were calculated for all periods up to 20 February 2012. As 20 February 2012 was our termination date, we adjusted year of fame to run from 21 to 20 February. Hence, Elvis Presley, whose first album was released in January 1956, was matched to the survival probabilities of the cohort of US white men aged 21 in 1955. Survival probabilities in the UK national life tables have no published CIs and therefore differences are assumed to be significant when matched population survival rates fall outside the 95% CIs for stars.

Cox regression analysis was used to identify relationships between age, sex, nationality, ethnicity, performer type (band or solo), age at fame and survival from point of fame. Other analyses used χ², Mann-Whitney U tests and backwards conditional logistic regression. Analyses were undertaken in Predictive Analytics Software (PASW) V.18. Ethical approval was not required as all data were accessed through publicly available materials.

Results

Between continents samples did not differ significantly in gender; although NA performers were younger (median year of birth; NA, 1965; EU, 1961; Z=2.650, p<0.01), reached fame recently (median year of fame; NA, 1992; EU, 1985; Z=4.288, p<0.001) and were less likely to be white (table 2). For both continents, performers’ genre was most likely to be pop/rock but the NA sample had higher levels of R&B and rap; EU stars featured more in electronica.

Table 2.

Characteristics of rock and pop star sample by geographical region

| Characteristics | Total |

Europe |

North America |

p* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| All | 1489 | 100 | 657 | 100 | 832 | 100 | |

| Male | 1375 | 92.3 | 613 | 93.3 | 762 | 91.6 | 0.216 |

| White | 1321 | 88.7 | 632 | 96.2 | 689 | 82.8 | <0.001 |

| Music genre | |||||||

| Pop/rock | 1350 | 90.7 | 616 | 93.8 | 734 | 88.2 | <0.001 |

| R&B | 42 | 2.8 | 3 | 0.5 | 39 | 4.7 | <0.001 |

| Electronica | 33 | 2.2 | 30 | 4.6 | 3 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| New age | 4 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.024 |

| Punk | 3 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.051 |

| Rap | 57 | 3.8 | 1 | 0.2 | 56 | 6.7 | <0.001 |

| Solo performer | 165 | 11.1 | 51 | 7.8 | 114 | 13.7 | <0.001 |

| Died by 20/02/2012 | 137 | 9.2 | 38 | 5.8 | 99 | 11.9 | <0.001 |

| Likely cause of death (% of dead) | |||||||

| 1 Chronic disorder (drug/alcohol)† | 10 | 7.3 | 1 | 2.6 | 9 | 9.1 | 0.193 |

| 2 Drug/alcohol overdose | 25 | 18.2 | 10 | 26.3 | 15 | 15.2 | 0.130 |

| 3 Accident (drug/alcohol related) | 7 | 5.1 | 4 | 10.5 | 3 | 3.0 | 0.074 |

| 4 Suicide | 4 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.6 | 3 | 3.0 | 0.901 |

| 5 Violence | 7 | 5.1 | 1 | 2.6 | 6 | 6.1 | 0.414 |

| 6 Other accident | 19 | 13.9 | 5 | 13.2 | 14 | 14.1 | 0.881 |

| 7 Cardiovascular disease | 21 | 15.3 | 4 | 10.5 | 17 | 17.2 | 0.334 |

| 8 Cancer | 25 | 18.2 | 8 | 21.1 | 17 | 17.2 | 0.599 |

| 9 Other | 18 | 13.9 | 3 | 10.5 | 15 | 15.2 | 0.483 |

| (1–5) All substance use or risk related | 53 | 38.7 | 17 | 44.7 | 36 | 36.4 | 0.368 |

*p (probability) describes differences between North American and European rock and pop stars. Percentages are compared using χ².

†Chronic drug and alcohol disorders include liver, kidney and gastrointestinal diseases linked with substance use.

Mortality and survival

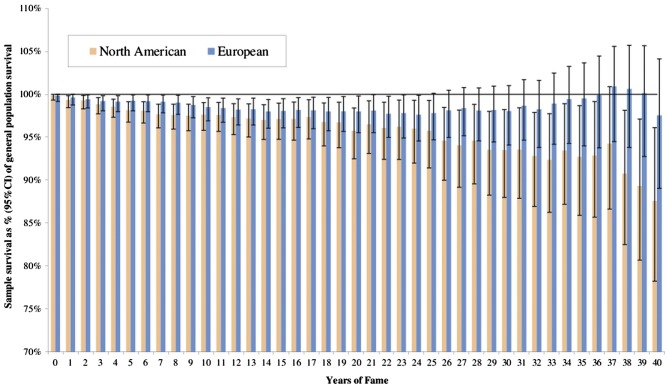

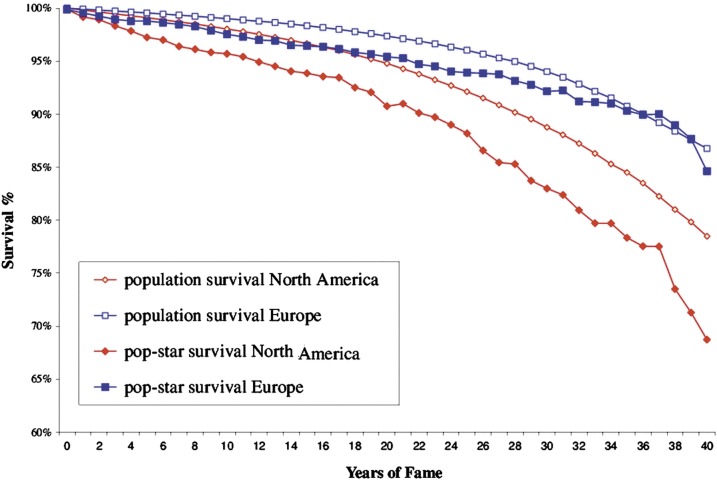

Across the whole sample 9.2% (n=137) of rock and pop stars had died (table 2). Despite being younger and reaching fame recently, more NA stars died. Median ages of death were 45.2 and 39.6 years for NA and EU stars, respectively (Z=0.688, p=0.492). Postfame mortality of stars differed significantly from matched general populations (figures 1 and 2). For NA stars, relative survival consistently decreased from 99.3% of matched population survival 1 year postfame to 87.6% 40 years postfame (R2=0.932; p<0.001). However, this trend was not apparent in EU stars (R2=0.024; p=0.881). Here, relative survival reduced postfame (99.6% of population survival 1 year postfame to 97.6% 24 years postfame) while from 25 years postfame survival recovered; returning to population levels 36 years postfame.

Figure 1.

North American and European rock and pop stars: age-standardised relative survival by years of fame. Footnote—sample survival percentage is calculated by comparison of rock and pop stars to age-matched, sex-matched and ethnicity-matched general populations in North America and Europe for each star from the year they reached fame.

Figure 2.

Comparative survival curves for North American and European rock and pop stars.

Star survival was examined by demographic and performer-related differences within performers. Solo performers were substantively more likely to have died (χ²=20.415, p<0.001) with unadjusted mortality being approximately double that of band-member only stars both for NA (22.8% vs 10.2%) and EU (9.8% vs 5.4%; table 3). Non-white ethnicity was associated with higher mortality while sex and age at fame were not (table 3). Examining survival since fame, while controlling for demographic confounders, identified NA nationality and solo performer status as having significantly higher hazard ratios (HRs) compared with being a member of a European band. Reaching fame from 1980 onwards was independently associated with a higher relative survival (table 3).

Table 3.

Crude mortality in rock and pop stars since point of fame and adjusted HRs using Cox survival analysis

| Characteristics | Crude death |

Adjusted HRs |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | N | Died (%) | χ² | p | HR | 95% CIs |

Wald | p | ||

| Type | Low | High | ||||||||

| Performer type and continent | European Band | 606 | 5.4 | 36.32 | <0.001 | Ref | 32.21 | <0.001 | ||

| European Solo | 51 | 9.8 | 1.12 | 0.44 | 2.88 | 0.06 | 0.812 | |||

| North American Band | 718 | 10.2 | 2.09 | 1.39 | 3.16 | 12.36 | <0.001 | |||

| North American Solo | 114 | 22.8 | 4.24 | 2.53 | 7.09 | 30.26 | <0.001 | |||

| Ethnicity | Not White | 168 | 15.5 | 8.93 | 0.003 | Ref | 0.057 | |||

| White | 1321 | 8.4 | ||||||||

| Sex | Female | 114 | 7.9 | 0.25 | 0.616 | Ref | 0.416 | |||

| Male | 1375 | 9.3 | ||||||||

| Age of fame | Under 25 years | 841 | 10.8 | 3.52 | 0.061 | Ref | 0.318 | |||

| 25 years or more | 648 | 8.0 | ||||||||

| Year of birth | ≤1955 | 529 | 19.7 | 108.95 | <0.001 | Ref | 0.780 | |||

| 1956–1969 | 509 | 4.5 | 0.644 | |||||||

| 1970 or later | 451 | 2.2 | 0.482 | |||||||

| Year reached | Before 1980 | 506 | 20.6 | 118.24 | <0.001 | Ref | ||||

| Fame | 1980 or later | 983 | 3.4 | 0.43 | 0.28 | 0.67 | 14.10 | <0.001 | ||

HR, hazard ratio; Ref, reference category.

ACEs in deceased stars

Almost half (47.2%) of stars who died from substance use or risk-related causes were reported to have had at least one ACE, compared with 25% of those dying through other causes (χ²=7.161, p<0.01). Under a third (30.8%) of deceased stars for whom no ACEs were identified died through substance use or risk-related causes, increasing to 41.9% of those with one ACE and 80% of those with two or more ACEs (χ²trend=11.77, p<0.001). As 46.3% of all ACEs identified were family separations, the analysis was repeated excluding this category but remained significant (χ²trend=7.88, p<0.01). Further, including possible confounders (performer type, continent, ethnicity, gender, age of fame, year of birth and year reached fame) in logistic regression analysis maintained the impact of increasing ACEs on cause of death (Wald=8.95, p<0.005; AOR 2.40; 95%CIs 1.35 to 4.25).

Discussion

Inevitably any study of famous people will have limitations. Our choice of music genres (table 1) aimed to capture only mainstream genres across both continents but some stars of, for instance, folk, country and jazz that were not included have substantial popular followings (eg, Damien Rice). Our definition of fame, while objective, is also likely to omit key individuals not included in the international polls we used despite success in record sales. Other analyses have chosen performers who topped sales charts7 but we used a broader definition as specific population groups can influence album purchases. For those performers included, extensive internet coverage of even somewhat forgotten stars meant that mortality could be relatively easily established. However, the exact cause of death was more difficult to identify. In particular, for some stars deaths from accidents and longer-term conditions may have been due to alcohol and drug use but would not be coded as such unless this was specifically reported in biographical resources.

For the first time we also attempted to extract information from public sources on adverse experiences stars had suffered while children. Two researchers collected such data independently and concordance between them was high. Data collection was limited to those who had died as death often generates greater media coverage and exposure of more sensitive personal details. However, the standard ACE tool does not capture all possible ACEs nor were all possible impacts of ACEs on mortality (eg smoking-related deaths) recorded. Moreover, the extent to which ACEs occur in living pop stars and consequently their relationship with overall risk of mortality is an important research questions for further work. Finally, it is unknown as to whether the impacts of ACEs and fame in other groups (eg, film stars and sports stars) would show similar relationships with mortality to those identified here. Consequently, this work on ACEs should be regarded as representing only an initial attempt to examine the impact of early life experiences in a unique group of individuals. However, while the limitations of this study are important to acknowledge, this methodology may currently be the only way to examine individuals who have moved, in some cases, from relative poverty to extreme affluence and who have followings larger than the population of entire countries.

Consistent with our findings, other recent studies have established the longer-term impact of rock and pop stardom on mortality; with reduced survival compared to the general population continuing well beyond the point of fame.7 However, studies have largely considered performers as a homogeneous group. As well as confirming the disproportionate mortality suffered by stars overall, here we have examined the impacts of nationality and performer type (eg, solo performer) on survival and impacts of ACEs on cause of death. Such findings raise a number of issues regarding the causes of increased mortality in stars that are central to protecting the health of rock and pop stars and addressing the appeal the hedonistic elements of rock and pop may have to their fan bases.

Overall, the differential between performers’ mortality and that of matched individuals in the general population increased with time since fame (figures 1 and 2). However, the difference in NA was substantively greater than that in EU. As previously reported,11 for both NA and EU samples the survival gap between stars and the population widened up to 25 years postfame. At this point, however, survival in EU stars only, begins recovery to general population levels. Reasons for this may include: different experiences of fame (eg, exposure to risk factors such as drugs and protective factors including professional well-being support), longer performing careers including reunion tours, and variations in access to universal health and social care. Critically, much premature mortality is hidden from fans who may be familiar with the acute impacts of alcohol and drugs on star mortality (eg, Amy Winehouse23) yet may not recognise the longer-term impacts on risks of physical (eg, cancer and heart disease) and mental health.24 25 Despite such links being well established even after substance use ceases,26 they are rarely discussed when stars suffer premature mortality in middle age. Moreover, as the mortality gap between stars and the general population increases with years since fame, these longer-term effects may be of greater significance than the acute risks associated with fame (figures 1 and 2). Even where substance use remains a direct contributor to premature death, the glorification of celebrity often eclipses discussion on the darker aspects of stars’ lifestyles.2 27

Our results suggest that some of the risks accredited to the rock and pop star lifestyle may in fact have more mundane roots akin to those leading to substance use and risk taking in wider populations. Recent studies have established strong relationships between ACEs, risk behaviour and poor-health outcomes in later life.15 28 For instance, the US Adverse Childhood Experiences study found that adults with four or more ACEs, compared to those with none, were at 7.4 times greater risk of alcohol addiction, 4.7 times greater risk of illicit drug use and 12.2 times greater risk of attempted suicide.28 Critically, risks of cancer were 1.9 times and heart disease 2.2 times greater as well.28 Adverse childhoods have also been associated with prescribed psychotropic medication use,29 as well as personality disorders in early adulthood,30 which have been linked to seeking fame.31 For rock and pop stars, we identified a relationship between increased ACEs and risk-related causes of death. Pursuing a career as a rock or pop musician may itself be a risky strategy and one attractive to those escaping from abusive, dysfunctional or deprived childhoods. Consequently, an industry with a concentration of individuals having acute and long-term health risks is perhaps not unexpected. However, consideration of childhood experiences brings into question whether even almost limitless resources in adulthood can undo the impacts of adverse childhoods,32 or whether such resource can feed predispositions to risk behaviours. Rock and pop star survival also seems to relate to whether they have pursued successful solo careers (table 3). While this may simply be a proxy for level of fame, with solo performers often attracting more attention than for instance a drummer or keyboard player in a band, it also raises the issue of peer support as a protective factor. Thus, further research should address whether bands provide a mutual support mechanism that offers protective health effects.

Pop stars are among the most common role models for children33 and surveys suggest that growing numbers are aspiring to pop stardom.34 A proliferation of TV talent shows (eg, X factor) and new opportunities created by the internet can make this dream appear more achievable than ever. Moreover, a growing body of research is linking celebrity worship and attachment to deficits in individuals’ lives, such as family breakdown, low emotional support, social isolation and poor mental health.2 35 36 Thus, vulnerable populations may be more likely both to develop strong attachments to rock and pop stars, and to emulate their health-damaging behaviours.2

The impact of recent developments in how rock and pop stars influence the wider population should also not be underestimated. The pop star Lady Gaga alone has over 20 million followers on Twitter37 and the tragic death of Whitney Houston generated over 2.5 million tweets within 2 h.38 While pop stars have had vast fan bases for decades, in recent years this relationship has moved from passive to active with stars now able to interact directly with fans through social media; increasing feelings of connectedness and arguably their influence. While stars may contribute to positive messages about youth behaviour and raise awareness of health causes (eg, domestic violence39) many remain icons for risk taking including drug use and alcohol misuse. For alcohol, glamorous associations with fame can be exploited by both alcohol and music companies through sponsorship and even brand placement in lyrics.40

This study raises some important issues relating to protecting both stars’ and would-be stars’ acute and long-term well-being in an industry that has turned recruitment of the next generation of celebrities into a global business. Fame inevitably increases opportunities to indulge established risk behaviours but recognition that substance abuse and other risk taking, even by music icons, may be rooted in ACEs is missing from public perception.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sara Wood and Lindsay Eckley for their assistance in identifying and collating information used in this study. We are grateful to Andrew Goodwin at Open Labs for his insights into social media and to Professor Peter W de Leeuw and Dr Adam Winstock for their reviewers’ comments.

Footnotes

Contributors: MAB designed the study, directed the analyses and wrote the manuscript. KH edited the manuscript and managed data collection and analysis. OS undertook data collection, literature reviews and edited the manuscript. TH completed the collection and analysis of actuarial data. KAH undertook data collection and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: All information used in this study is already publicly available.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data sets used in this study are available from the corresponding author (M.A.Bellis@ljmu.ac.uk) to those wishing to undertake collaborative work on health aspects of rock and pop fame.

References

- 1.Rothman EF, Nagaswaran A, Johnson RM, et al. U.S. tabloid magazine coverage of a celebrity dating abuse incident: Rihanna and Chris Brown. J Health Commun Published Online First 4 April 2012;17:733–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rojek C. Fame attack: the inflation of celebrity and its consequences. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boden S. Dedicated followers of fashion? The influence of popular culture on children's social identities. Media, Culture Society 2006;28:289–98 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niederkrotenthaler T, Fu KW, Yip PS, et al. Changes in suicide rates following media reports on celebrity suicide: a meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:1037–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman S, McLeod K, Wakefield M, et al. Impact of news of celebrity illness on breast cancer screening: Kylie Minogue's breast cancer diagnosis . Med J Aust 2005;183:247–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro H. Waiting for the man: the story of drugs and popular music. London: Helter Skelter Publishing, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolkewitz M, Allignol A, Graves N, et al. Is 27 really a dangerous age for famous musicians? Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2011;343:d7799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, et al. Deaths: preliminary data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2011;59:1–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office for National Statistics Death registrations by single year of age, United Kingdom. 2010. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77–240172. (accessed Jul 2012)

- 10.Jones L, Bellis MA, Dedman D, et al. Alcohol-attributable fractions for England: alcohol-attributable mortality and hospital admissions. Liverpool: Centre for Public Health, Liverpool John Moores University, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellis MA, Hennell T, Lushey C, et al. Elvis to Eminem: quantifying the price of fame through early mortality of European and North American rock and pop stars. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:896–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNamara K. The paparazzi industry and new media: the evolving production and consumption of celebrity news and gossip websites. Int J Cultural Stud 2011;14:515–30 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roach M. Take that: now and then. London: Harper Collins Publishers, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robb J. The Stone Roses: the reunion edition. London: Random House Group Ltd, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;256:174–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roustit C, Renahy E, Guernec G, et al. Exposure to interparental violence and psychosocial maladjustment in the adult life course: advocacy for early prevention. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:563–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brim OG. Look at me! The fame motive from childhood to death. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Napier-Bell S. Black vinyl white powder. London: Ebury Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larkin C. All-time top 1000 albums. 3rd edn London: Virgin Publishing, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ). http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/en/. (accessed Jul 2012)

- 21.Demographic Analysis Unit Period and cohort life expectancy tables. Office for National Statistics, 2012

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Life tables. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/life_tables.htm (accessed Jul 2012)

- 23.Shaw RL, Whitehead C, Giles DC. ‘Crack down on the celebrity junkies’: does media coverage of celebrity drug use pose a risk to young people? Health Risk Soc 2010;12:575–89 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet 2009;373:2223–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuepper R, van Os J, Lieb R, et al. Continued cannabis use and risk of incidence and persistence of psychotic symptoms: 10 year follow-up cohort study. BMJ 2011;342:d738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarl J, Gerdtham U-G. Time pattern of reduction in risk of oesophageal cancer following alcohol cessation—a meta-analysis. Addiction 2011;107:1234–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang B. Whitney Houston's death: why the media sidestepped the lurid details. 14 February 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/02/14/idUS307174055220120214. (accessed Jul 2012)

- 28.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anda RF, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and prescribed psychotropic medications in adults. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:389–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brown J, et al. Childhood maltreatment increases risk for personality disorders during early adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiat 1999;56:600–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinsky D, Young M. The mirror effect: how celebrity narcissism is endangering our families—and how to stop them. New York: Harper Collins, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Wood S, et al. National five-year examination of inequalities and trends in emergency hospital admission for violence across England. Injury Prev 2011;17:319–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Read B. Britney, Beyonce, and me—primary school girls’ role models and constructions of the ‘popular’ girl. Gender Educ 2010;23:1–13 [Google Scholar]

- 34.1 October 2009. Children would rather become popstars than teachers or lawyers. The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews/6250626/Children-would-rather-become-popstars-than-teachers-or-lawyers.html (accessed Jul 2012)

- 35.Cheung C, Yue XD. Idol worship as compensation for parental absence. Int J Adolesc Youth 2012;17:35–46 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maltby J, Day L, McCutcheon LE, et al. Personality and coping: a context for examining celebrity worship and mental health. Br J Psychol 2004;95(pt 4):411–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Topping A. Lady Gaga racks up 20 million Twitter followers. The Guardian 6 March 2012. http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2012/mar/06/lady-gag-20-million-twitter-followers (accessed Jul 2012)

- 38.Nakashima R. Whitney Houston estate to gain; questions remain. The Guardian 15 February 2012. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/feedarticle/10094205 (accessed Jul 2012)

- 39.The United States Department of Justice 100 celebrities ‘join the list’ to raise awareness of violence against women. 3 December 2009. http://blogs.justice.gov/main/archives/458 (accessed Jul 2012).

- 40.Primack BA, Nuzzo E, Rice KR, et al. Alcohol brand appearances in US popular music. Addiction 2011;107:557–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.