Abstract

Objective

Administering medication to hospitalised infants and children is a complex process at high risk of error. Failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) is a proactive tool used to analyse risks, identify failures before they happen and prioritise remedial measures. To examine the hazards associated with the process of drug delivery to children, we performed a proactive risk-assessment analysis.

Design and setting

Five multidisciplinary teams, representing different divisions of the paediatric department at Padua University Hospital, were trained to analyse the drug-delivery process, to identify possible causes of failures and their potential effects, to calculate a risk priority number (RPN) for each failure and plan changes in practices.

Primary outcome

To identify higher-priority potential failure modes as defined by RPNs and planning changes in clinical practice to reduce the risk of patients harm and improve safety in the process of medication use in children.

Results

In all, 37 higher-priority potential failure modes and 71 associated causes and effects were identified. The highest RPNs related (>48) mainly to errors in calculating drug doses and concentrations. Many of these failure modes were found in all the five units, suggesting the presence of common targets for improvement, particularly in enhancing the safety of prescription and preparation of endovenous drugs. The introductions of new activities in the revised process of administering drugs allowed reducing the high-risk failure modes of 60%.

Conclusions

FMEA is an effective proactive risk-assessment tool useful to aid multidisciplinary groups in understanding a process care and identifying errors that may occur, prioritising remedial interventions and possibly enhancing the safety of drug delivery in children.

Keywords: Qualitative Research, Pediatrics, Drugs Administration

Article summary.

Article focus

Medication errors are the most common mistakes made in the hospital setting.

In paediatric populations, their incidence is higher than in adults and their effects potentially more harmful.

To examine the hazards associated with drugs delivery in children, a proactive risk assessment was performed.

Failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) can identify and prioritise risk of patients harm in a complex process and allow to point out opportunity for improving medication safety.

Key messages

Medication safety is possibly enhanced by reducing the likelihood of failing and number of opportunities for error.

FMEA provides a useful method, even in a pediatrics setting, for describing the riskiness of complex processes and guiding prioritisation of improvement efforts.

Strengths and limitations of this study

FMEA is an analytic method for identifying potential failure modes and their causes before they happen, to grade their potential impact on the final outcome of a process and to guide the prioritisation of improvement changes.

It potentially ensures a relevant and sustainable reduction in the risk of medication errors, promoting process changes and patient safety and improving the cooperation and synergies between healthcare operators.

Its relevance to clinical practice, therefore, strongly relies on the experience and style of the facilitator and composition of the team.

FMEA also entails a lot of time, effort and resources and should be completed in identifying the high risks by different sources of information besides the experience and knowledge of team components.

Introduction

Administering drugs is a multistep procedure at high risk of failure in any age group. Patients’ characteristics, types of drug and routes of administration (intravenously as a bolus or by continuous infusion) coincide with different risk profiles and potential failures.1–2

Newborns and children are particularly challenging patient groups when it comes to ensuring the safe use of medicines. Errors in drug administration occur three times more frequently in the paediatric population than in adults and, within this paediatric population, they affect inpatients more often than outpatients.3 The need to calculate drug doses to suit a patient's gestational age, weight or surface area, to use special dilutions and to manipulate the drugs supplied are some of the probable reasons why the process of prescribing and administering drugs to children is at higher risk of ‘failure’ than in the case of adult patients. It has already been documented that errors in drug prescription and administration are the most common types of mistake made in neonatal and paediatric units, with a prevalence of up to 11% and up to 17%, respectively.4

Action is therefore urgently needed to reduce these risks. Unlike what happens in the USA and some European countries, where prescriptions for medication have to be reviewed by a pharmacist or a qualified and licensed independent practitioner, no such rigid, mandatory recommendations have been clearly formulated in Italy or widely implemented by the Ministry of Health, leaving institutions to find their own solution to the problem of medical prescription errors.5 Unquestionably, it is still relatively common for nurses to be involved in preparing and administering drugs in healthcare institutions like ours. This makes it particularly important to take action to reduce the risks related to these procedures.

Failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) is a method used in industry to assess complex processes according to a standardised approach with a view to identifying the elements that carry a risk of causing harm and, consequently, prioritising remedial measures. It is based on the concept that a risk is related not only to the likelihood of a failure occurring, but also to the severity of the failure's consequences and the feasibility of detecting and intercepting a failure before it occurs. The FMEA approach also enables each of the elements comprising a process under investigation to be attributed a cumulative numerical value, the risk priority number (RPN), which can be used to prioritise the action to be taken because it is a numerical rating of the severity, probability and detectability of each failure mode.6 A programme called ‘Paracadute’ (Project for reducing the risk of errors in critical drug delivery), based on FMEA, was adopted at five units of the paediatric department at the University of Padua (Italy) to assess the impact of process changes on the occurrence and likelihood of detection of failure modes relating to drug administration.

The aim of the project was to understand the failure modes associated with medication use in hospitalised children through a proactive risk analysis (FMEA); the multidisciplinary teams identified, analysed and prioritised failure modes by calculating RPNs and introduced corrective actions as an opportunity to improve patient safety.

This is one of the few published experiences of the use of FMEA in the process of delivering healthcare for children.

Methods

Setting and study timetable

The project was conducted at the paediatric department at the University Hospital in Padua, Italy, a tertiary care paediatric centre with 213 beds; it receives 9000 inpatients and 4200 day-hospital admissions a year, and provides care in almost all subspecialties of medical and surgical paediatric care. It is also an academic institution providing undergraduate training in paediatrics for medical students, running a 3-year undergraduate course for paediatric nurses, hosting a large paediatric residency programme and advanced professional masters courses.

Each inpatient area has its own therapy order form, where physicians write their prescriptions and nurses record the actual administration of the prescribed therapy. All prescriptions are, still, calculated manually by physicians and handwritten on the therapy order form. Drugs and intravenous fluid solutions are prepared by registered nurses in each area and on each work shift who are also responsible for administering them to patients (the department has no centralised pharmacy to prepare prescriptions, apart from parenteral nutrition). Finally, the actual administration of medicines is recorded by the nurse (who signs in a dedicated box), who also indicates the time of administration on the same therapy order form as was used by the prescribing physicians. The nursing staff are also responsible for the drug inventory within the unit. Restocking the ward inventory is done via pre-established list and is supplied by the central pharmacy 1 day a week. Although with different levels of responsibility, and always under supervision, trainee nurses and paediatric residents are also involved in delivering therapies.

The scheme to review the complex process of ordering and administering drugs to children was decided by the Paediatric Department Board and developed by a multidisciplinary working group. It was considered as ‘on-the-job training’. An external facilitator with training on the FMEA methodology guided all the activities and finally verified that all changes introduced were effectively in place. Five multidisciplinary teams took part in the project, representing the paediatric and neonatal intensive care units (PICU and NICU), the paediatric haematology–oncology service (Onco-haematology), the general paediatric ward (General Ped) and the emergency care unit (Acute Care). This project was part of an ongoing quality improvement programme, so Institutional Ethics Committee approval was not required. The scheme got underway in June 2010 and was completed by December 2010; the subsequent 6 months were used to monitor the process. All the members of the different teams initially spent four full days learning about the FMEA methodology and planning the activity guided by a consultant with extensive experience in proactive risk assessment. The first meeting included an overview of FMEA and example of the process scheme. Following sections included guided failure mode analyses, rating, prioritisation of risk and planning activities to reduce errors in the process of drugs delivery. The time spent by the member of each team to complete the process was estimated at about 100 days.

Composition of the team and analysis of the drug-delivery process

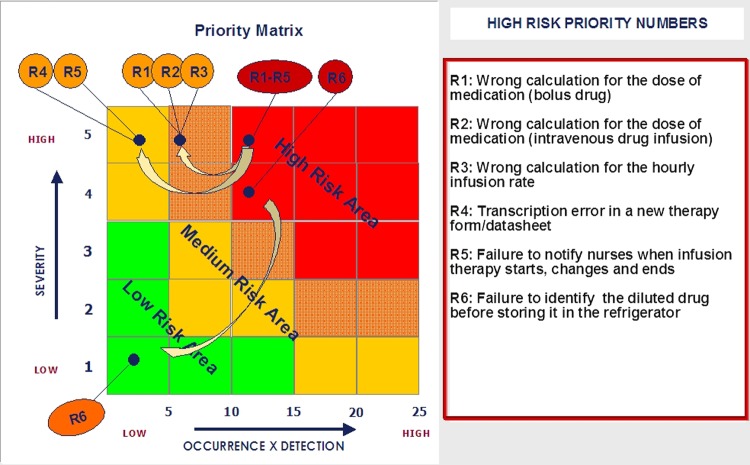

Each team consisted of eight members between the frontline staff who were familiar with the process, including doctors, residents, nurses, and patients’ safety experts, risk management experts and/or a quality improvement specialist. A pharmacist, a representative of service for health professions and an administrative officer were involved when specific identified risks where analysed. As FMEA is performed by mapping the steps in a complex process and then identifying failure modes for each steps, their responsibilities were: (1) to identify and describe the steps involved in the process of prescribing, preparing and administering drugs at their respective units (producing flow diagrams); (2) to highlight possible sources of errors at each step; (3) to clarify the reason why a failure might occur in completing each step and (4) to quantify the severity of the effects of such potential failures. Each team was then asked to independently estimate (score) the likelihood of a specific error occurring, its severity and the chances of the error being detected and intercepted before it could occur, calculating the specific RPN. This permitted the prioritisation of the multiple failure modes, identifying those at greater risk of harm. Each team identified from this analysis the higher risk failure modes as those with the highest severity and frequency scores and lowest likelihood of detection, plotted in the red or orange area of the priority matrix (figure 1), and developed corrective actions assigning them an appropriate priority.

A value in the range of 1–5 was attributed to each step in the drug-delivery process to quantify the potential occurrence of a failure (O); the severity of its potential negative impact on the overall process (S); and the chances of the failure being detected and intercepted before it occurs (D), according to the Joint Commission (JCAHO) classification.6 All the numerical scores were directly proportional to the estimated frequency of the failure, the severity of its impact and the difficulty of intercepting it. Values of 5 thus reflected a near-certain likelihood of failure, the effects of which would be fatal, and there was practically no chance of the failure being detected before it caused harm. The agreement on the final score to attribute to each critical step in the complex process of ordering and administering drugs was reached by asking each member of the team to quantify their personal estimation of the related risk according to previously defined, precise and strict criteria, followed by a shared discussion in the case of overt discordance (table 1).

Table 1.

Rating scales used to assign values to the occurrence (O), severity (S), and detection (D) scores in the failure mode and effect analysis of the drug administration process

| Occurrence (O)| |

Severity (S) |

Detection (D) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Failure mode probability | Score | Description of injury | Score | Likelihood of detection |

| 1 | Remote: failure unlikely to occur (happening in 1 in 10000 episodes observed) | 1 | No injury or patient monitoring alone | 1 | Very high: detected 9/10 times |

| 2 | Low: relatively rare failure (happening in 1 in 1000 episodes observed) | 2 | Temporary injury needing additional intervention or treatment | 2 | High: detected 7/10 times |

| 3 | Moderate: occasional failure (happening in 200 episodes observed) | 3 | Temporary injury with longer hospital stay or increased level of care | 3 | Medium: detected 5/10 times |

| 4 | High: recurrent failure (happening in 1 in 100 episodes observed) | 4 | Permanent effects on body functions | 4 | Low: detected 2/10 times |

| 5 | Very high: common failure (happening in 1 in 20 episodes observed) | 5 | Death or permanent loss of major body functions | 5 | Remote: detected 0/10 times |

The risk priority number (RPN) is calculated by multiplying the O, S and D scores.

The numerical value obtained by multiplying these three factors is the RPN (O×S×D), which was used to grade the relevance of each step, in terms of its overall influence on the process. The RPN therefore enabled the elements most likely to contribute to serious drug administration failures to be pinpointed. The maximum RPN was 125. The RPN was also used to establish the priority of remedial measures. All data were stored in an electronic FMEA database.

The hazard analysis was completed by plotting the RPNs of higher risk failure modes in a priority matrix (figure 1), which is a graph divided into four coloured areas reflecting different levels of priority for action: Area 1 (red) urgent action required; area 2 (orange) prompt action required; area 3 (yellow) scheduled action required; area 4 (green) monitoring required.

Figure 1.

Priority matrix, plotting severity against probability (the product of O×D) before and after applying failure mode and effect analysis.

The priority matrix gave each team graphical evidence of which steps, in the complex process of administering drugs, more urgently needed corrective action to reduce the risk of failures.

After implemented any corrective actions in relation to the higher risk of failure identified, their efficacy was evaluated through tests conducted in the wards and supervised by the consultant according to international standards; these statistically significant test results formed a dataset that was collected with a view to understanding whether the action taken to reduce the risk of errors was effective. Implementing these new activities consented to estimate new occurrence, severity and detection scores for the process after implementing the recommended action and calculate the resulting RPN.7 The modified activities were then monitored for several months.

Results

The five teams developed detailed process map for own process of medication use, identifying failure modes for each step. As process step may be vulnerable to multiple failure modes, the calculation of RPNs permitted to identify the failure modes that pose the greatest risk of harm. Table 2 displays the number of process steps and the high-risk failure modes that teams identified in multiple FMEAs with the RPNs count before and after improvement plans were realised. The number of process steps varies between units with different level of intensity care.

Table 2.

Number of process steps and failure modes identified in paediatric medication use multiple failure mode and effect analyses (FMEAs)

| Paediatric units and process phases | Process steps | Total failure modes | High-risk failure modes before FMEA | RPNs1 | High-risk failure modes after FMEA | RPNs2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° (%) | N° (%) | N° (%) | N° (%) | |||

| NICU | ||||||

| Supplying | 25 (29.4) | 47 (23.0) | 0 | |||

| Prescribing | 18 (21.2) | 44 (21.6) | 5 (62.5) | 320 | 2 (25) | 144 |

| Preparation | 22 (25.9) | 41 (20.1) | 3 (37.5) | 208 | 2 (25) | 56 |

| Administering | 15 (17.6) | 44 (21.6) | 0 | |||

| Monitoring | 5 (5.9) | 28 (13.7) | 0 | |||

| Total | 85 | 204 | 8 | 496 | 4 (50) | 200 |

| PICU | ||||||

| Supplying | 20 (26.3) | 37 (22.7) | 0 | |||

| Prescribing | 22 (28.9) | 49 (30.1) | 7 (87.5) | 420 | 4 | 140 |

| Preparation | 15 (19.7) | 26 (16.0) | 1 (14.39 | 48 | 0 | 1 |

| Administering | 13 (17.1) | 32 (19.6) | 0 | |||

| Monitoring | 6 (7.9) | 19 (11.7) | 0 | |||

| Total | 76 | 163 | 8 | 468 | 4 (50) | 151 |

| Acute care | ||||||

| Supplying | 27 (29.7) | 37 (22.7) | 0 | |||

| Prescribing | 30 (33.0) | 49 (30.1) | 6 (66.7) | 270 | 0 | 120 |

| Preparation | 15 (16.5) | 26 (16.0) | 2 (22.2) | 93 | 1 | 48 |

| Administering | 13 (14.3) | 32 (19.6) | 0 | |||

| Monitoring | 6 (6.6) | 19 (11.7) | 1 (11.1) | 45 | 0 | 20 |

| Total | 91 | 163 | 9 | 408 | 1 | 188 |

| Onco-haematology | ||||||

| Supplying | 9 (18.8) | 14 (15.5) | 0 | |||

| Prescribing | 12 (25.0) | 23 (25.5) | 6 (100) | 288 | 2 | 124 |

| Preparation | 17 (35.4) | 27 (30.0) | 0 | |||

| Administering | 12 (25.0) | 18 (20) | 0 | |||

| Monitoring | 3 (6.3) | 8 (8.8) | 0 | |||

| Total | 53 | 90 | 6 | 288 | 2 | 124 |

| General Ped | ||||||

| Supplying | 14 (27.5) | 25 (30.4) | 4 (66.7) | 177 | 1 | 66 |

| Prescribing | 9 (17.6) | 14 (17.0) | 1 (16.7) | 48 | 1 | 24 |

| Preparation | 19 (37.3) | 27 (32.9) | ||||

| Administering | 6 (11.8) | 11 (13.4) | 1 (16.7) | 48 | 1 | 24 |

| Monitoring | 3 (5.9) | 5 (6.0) | ||||

| Total | 51 | 82 | 6 | 273 | 3 | 114 |

RPNs1: original process-RPNs2 modified process.

General Ped, general paediatric ward; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit; RPN, risk priority number.

Failure modes

A total of 37 high-risk failures were identified, plotted in areas 1 (=red) and 2 (=orange) of the priority matrix, with 71 associated causes and effects (table 3).

Table 3.

High-risk failure-modes identified across multiple medication use failure mode and effect analysis

| High-risk failure modes | Process phases | NICU | PICU | Acute care | Onco-haematology | General Ped | N° High-Risk Failure Modes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error in using the Kanban system for re-order drugs | Supplying | ▪ | 1 | ||||

| Failure to check pharmacy supplies (to cross-check drugs ordered against drugs delivered and to correlate the drug package with the patient) | Supplying | ▪ | 3 | ||||

| Error in calculating the dosage of medication (Failure to measure patient's weight and height, failure to correctly prescribe bolus and continuous infusion drugs, ‘high-risk’ intravenous drugs, dilutions, infusion rate, frequency of administration) | Prescription | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 8 |

| Failure to check dose and frequency of administration | Prescription | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 4 | |

| Erroneous prescription of therapy on the order form (writing error and transcription error on a new therapy form, oral prescription over the phone during the night) | Prescription | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 3 | ||

| Incomplete reassessment of the daily clinical status and lack of written notes and/or spoken information on changes in clinical situation | Prescription | ▪ | 2 | ||||

| Failure to notify to the nurse a new medication order (either for bolus or and infusion, for changes and end of infusion) | Prescription | ▪ | ▪ | 4 | |||

| Failure to check chemotherapy components | Prescription | ▪ | 1 | ||||

| Unavailability of drugs at the time of patient's transfer owing to lack of medication reconciliation, and urgent need for drugs from the pharmacy | Prescription | ▪ | 1 | ||||

| Misinterpretation of prescription by the nurse owing to illegible handwriting or shortcuts | Prescription | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | 3 | ||

| Failure to consult handbook to check proper dilution, concentration, compatibility, rate of administration, photosensitivity and method of administration | Preparation | ▪ | 2 | ||||

| Erroneous calculation of the prescribed dose of medication (incorrect choice of proportions to obtain the right dose in ml, or of the proportions needed to reach the maximum concentration of the drug) | Preparation | ▪ | ▪ | 1 | |||

| Failure to identify type of drug in syringe during infusion and before storing it in the refrigerator | Preparation | ▪ | ▪ | 2 | |||

| Failure to explain to parents how to monitor the drug's administration | Administering | ▪ | 2 | ||||

| Inadequate monitoring of potential adverse effects | Monitoring | ▪ | 1 | ||||

| Total high-risk failure modes | 8 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 37 |

General Ped, general paediatric ward; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit.

▪, Error was found in the unit selected

None of the steps in the drug administration process were free of potential failure modes, but the prescription and preparation of the drugs emerged as the most vulnerable steps (with RPNs over 48). The most critical element in the prescribing of drugs was the calculation of the doses required, especially for infusion drugs (RPN 60). This high-risk failure mode was found in all the paediatric units, and was believed to be related to doctors and nurses not having reference material available with all the pertinent information on the methods for preparing and administering the drugs, and the proportions and formulas for adapting the drugs’ dosage to a given patient.

Also, all the teams listed other causes of high-risk failures, relating to defect in checking dose and mode of administration drug, erroneous prescription of therapy on the order form and misinterpretation by the nurse, possibly due to the lack of a computer-based technology. Four units treated also as high-risk related to different levels of expertise between doctors and nurses regarding how drugs should be prepared and administered. Only in the general paediatric unit were found high-risk failures relating to the unsafe supply and storage and to the administration phase; failures in the monitoring phase were found only in the acute care unit.

Risk-reduction strategies

Each unit independently developed plans for new corrective actions focused only on the higher risk failure modes identified, and a representative set of the corrective actions is summarised in table 4. Some of the remediation strategies were common to all five units as for the prescription phase.

Table 4.

Selected new activities to address high-risk failure modes affecting the five paediatric drug-delivery processes

| Process phase | New activities of improvement plans | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Supplying | Change the collection point for Kanban card* | General Ped |

| Supplying | Check consistency and sign delivery note. Preprinted label to identified patient with barcode. New form for re-ordering galenic drugs | General Ped |

| Prescription | Quiet place for preparing prescriptions without distraction. Single formulary. Prescription of active ingredient, in mg. Tables for standard doses and dilutions. Healthcare worker involved to get daily weight of patients | NICU, PICU, PED.Acute Care, Onco-haematology |

| Prescription | Doctors doublecheck and double-sign | NICU, PICU, PED.Acute Care, Onco-haematology, General Ped |

| Prescription | Clearly understandable written prescription. Preventive written prescription necessary or written prescription by doctor on duty | PICU, PED. Acute Care, Onco-haematology |

| Prescription | Daily discussion of clinical situation and ongoing therapy between resident and attending physicians. Daily notes by attending physician | NICU |

| Prescription | Yellow Post-it on therapy folder. Nurse signs | NICU, PICU |

| Prescription | Green label for chemotherapy. Nurse doublechecks and doublesigns for preparation; and nurse signs for drug administration | Onco-haematology |

| Prescription | List of medication available prior to patient's transfer. (medication reconciliation) | Onco-haematology |

| Preparation | Write clearly and comprehensibly. Nurse doublechecks and doublesigns. Easy-to-read therapy form. Pre-printed label with barcode | PED. Acute Care, General Ped, Onco-haematology |

| Preparation | Pre-printed label briefly reports the essential notes for correct dilution, compatibility, rate of administration and the sign of the nurse who prepared the medication | NICU, PED. Acute Care |

| Preparation | Facsimile of the proportions required on hand in the room | NICU |

| Preparation | All diluted drugs are discarded once used | NICU, PICU |

| Administering | Written instructions for parents involved in drug administration | General Ped |

| Monitoring | Check vital signs and site of infusion for certain drugs | PED. Acute Care |

*The Kanban card is a message that alerts to the depletion of product stocks and triggers their replenishment.

General Ped, general paediatric ward; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit.

After the implementation of these corrective actions, none of the steps in the revised drug administration process had an RPN>32. The reduction in the RPNs for the higher risks was around 60% at almost all units, and 23 of 37 higher risk failure modes identified with FMEA were now plotted in the low-risk area (yellow and green area of the priority matrix).

At the end of the FMEA process, a plenary session was held where each team reported on the results achieved in terms of corrective action and changes introduced in clinical practice. Clinical audits conducted by the team leader 3 and 6 months after completing the FMEA process confirmed that the main clinical changes and innovations introduced were still firmly in place.

Discussion

We performed FMEAs in five paediatric units at a large paediatric department to understand how the potential vulnerabilities associate with the process of medication use to hospitalise children. We found that processes of drugs administration varied between the paediatric units and were vulnerable to many failure modes; however, the majority of vulnerabilities were common to all paediatric units. High-risk failure modes identified spanned the medication-use process and represent potential target for improvement. In our experience, FMEA proved an effective method for analysing the complex process of prescribing and administering drugs to children. It soon enabled a collaborative team effort to generate a comprehensive overview of the different steps encompassing the process, a careful assessment and grading (in terms of the risk of each failure mode) of the steps at risk, and to proactively promote corrective actions to prevent adverse drug events from occurring.

A major advantage of FMEA over other quality improvement schemes is the unique information gathered that makes it easy to identify the priorities of any actions required for improvement, lowering the riskiness of the medication-use process. It enabled changes to be made to daily practice that were promptly and willingly accepted by all the personnel in the different teams, mostly owing to the team's initial approach to the problem. At our institution, the FMEA approach was chosen as a preliminary method for conducting a risk analysis on drug delivery activities, because it afforded the opportunity for a more comprehensive analysis of the process than other tools that are still being implemented, such as a common cause analysis on medication errors identified by means of voluntary incident reporting, and ‘trigger tool’ analysis followed by the use of the ‘model of improvement’.8

The efficacy of FMEA has been criticised in the literature for low accuracy, and until its validity is further explored,9 we acknowledge that, with a view of improving drug safety, it is also important to report near misses as well as actual medication errors because these quality improvement methods enable all, even potential, erroneous situations to be analysed and lessons to be learned from pooled experiences so that improvements can be further refined.10 Such methods are also being implemented at our institution.

This report is one of the few published so far on the use of FMEA in paediatric practice, although the method has been recommended by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organisations11. Apkon et al12 reported using FMEA to improve the safety of intravenous drug infusions in children. Another study identified the priorities for medication safety in the neonatal intensive care unit using the FMEA framework.13 The objective was to increase staff awareness of medication safety issues and to reduce errors in drug-dose calculations, timing and route of administration, and infusion pump settings.

In the complex process of prescribing and administering drugs on the part of all five teams considered, the single step at highest risk of error was, as expected, the calculation of the dose of drug. Most of the errors in this activity related to the use of the wrong equations rather than to arithmetical errors.14 The corrective actions adopted in our conventional, handwritten prescription setting: implementing a doublechecking practice; using the same reference booklets; adopting a single drug prescription form (the therapy order form) to avoid multiple transcriptions of prescriptions; implementing the practice of nurses’ doublechecking, particularly when calculating doses and concentrations; administering only properly labelled medication and disposing of leftover drugs are well-known interventions to reduce the risk related to drug-delivery process.15 16 It was demonstrated that all these changes were still in place in the follow-up analysis performed together with the FMEA supervisor, some months later.

Although the goal of our FMEA project was to identify vulnerabilities in the paediatric medication process, this initiative also helped our organisation to endorse further initiatives to support safe-prescribing and safe-administering of medications, as the development of an electronic-order entry system for paediatric drug delivery. Taking a more modern perspective, the introduction of computerised calculators would naturally represent the ideal solution for many of the critical steps that we identified.17 Thus, further research is needed to evaluate the impact of these systems on healthcare delivery.18

This study has some limitations. As a single-institution study, the findings reflect the care delivery model at one paediatric department and, although many features are common to other healthcare organisations, others reflect local arrangements. For these reasons, the results might not be completely generalised to other paediatric organisations. FMEA permit to identified higher risk of failure modes through a meticulous, time-intensive and resource-intensive methodology and its successful completion is highly dependent on the team member's aptitude and on facility's and team member's commitment to introduce corrective measures in clinical practice. For these reasons, it is important to create a multidisciplinary team of front-line people who know perfectly the process guided by an experienced facilitator, which can improve the consistency of an FMEA programme and also minimise the number of hours it takes to complete an FMEA.

Conclusions

In today's healthcare world, patient-safety issues are a major concern, particularly in the paediatric population. With a view to reduce the risk of medication errors and to improve patient safety, the data presented here entitle us to say that tools such as FMEA enable a prospective analysis of the process of drug delivery to review potential failure modes and their associated causes and to assess which risks have the greatest concern, stimulating the most urgent improvement effort in clinical practice to prevent errors before they occur. After 1 year, we were able to demonstrate a reduction in the potential for errors being made and to identify opportunities to improve medication safety in children.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study; data acquisition, analysis and interpretation and drafting of the article or its critical revision for important intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This project was part of an ongoing quality improvement programme, so Institutional Ethics Committee approval was not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting. Pediatrics 2003;112:431–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaushal R. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA 2001;285:2114–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferranti J, Horvat M, Cozart H, et al. Reevaluating the safety profile in pediatrics: a comparison of computerized adverse drug event surveillance and voluntary reporting in the pediatric environment. Pediatrics 2008;121:1201–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otero P, Leyton A, Mariani G, et al. Medication errors in pediatric inpatients: prevalence and results of a prevention program. Pediatrics 2008;22:737–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Italian Ministry of Health Recommendation n° 7 for the prevention of death, coma and serious injury derived from errors in pharmacological therapy. 2008. http//www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pagineAree_1637_listaFile_itemName_6_file.pdf (accessed August 2012).

- 6.Joint Commission Resources. Joint Commission International Failure Mode and Effects Analysis in Health Care: proactive risk reduction. 3rd edn. 2010

- 7.International Organization for Standardization ISO 19.011. Guidelines for quality and/or environmental management systems auditing. February 2012 and Internal Audit Association, International Standards for professional practice of internal auditing-mak-up version for the standards changes, 2010

- 8.Rozich JD, Haraden CR, Resar RK. Adverse drug event trigger tool: a practical methodology for measuring medication related harm. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:194–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shebl NA, Franklin BD, Barber N. Failure mode and effects analysis outputs: are they valid? BMC Health Ser Res 2012;12:150–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guffey P, Szolnoki J, Caldwell J, et al. Design and implementation of a near-miss reporting system at a large academic pediatric anesthesia department. Pediatr Anesth 2011;21:810–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations An introduction to FMEA. Using failure mode and effects analysis to meet JCAHO's proactive assessment requirement. Failure mode and effect analysis . Health Devices 2002;31:223–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apkon M, Leonard J, Probst L, et al. Design of a safer approach to intravenous drug infusions: failure mode effects analysis. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:265–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunac DL, Reith DM. Identification of priorities for medication safety in neonatal intensive care. Drug Saf 2005;28:251–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lesar TS. Errors in the use of medication dosage equations. Acta Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998;152:340–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (1999 June) Recommendations to enhance accuracy of administration of medications. 2009. http://www.nccmerp.org/council/council1999–06-29.html (accessed August 2012).

- 16.Easty A, Moser J, Trip K, et al. Checking it twice: Devloping and implementing an effective method for independent-double checking of high-risk clinical procedures. 2008. htpp//www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/English/research/cpsiResearchCompetitions/2005/Pages/Easty.aspx (accessed August 2012).

- 17.Van Rosse F, Maat B, Rademaker CMA, et al. The effect of computerized physician order entry on medication prescription errors and clinical outcome in pediatric and intensive care: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2009;123:1184–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han YY, Carcillo JA, Venkataraman ST, et al. Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system. Pediatrics 2005;116:1506–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.