Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the clinical effectiveness of soft tissue injury management by emergency nurse practitioners (ENPs) and extended scope physiotherapists (ESPs) compared to the routine care provided by doctors in a UK emergency department (ED).

Design

Randomised, pragmatic trial of equivalence.

Setting

One adult ED in England.

Participants

372 patients were randomised; 126 to the ESP group, 123 to the ENP group and 123 to the doctor group. Participants were adults (older than 16 years) presenting to the ED with a peripheral soft tissue injury eligible for management by any of the three professional groups. Patients were excluded if they had any of the following: injury greater than 72 hours old; systemic disease; dislocated joints; recent surgery; unable to give informed consent (eg, dementia), open wounds; major deformities; opiate analgesia required; concurrent chest/rib injury; neurovascular deficits and associated fracture.

Interventions

Patients were randomised to treatment by ESPs, ENPs or routine care provided by doctors (of all grades).

Main outcome measures

Upper-limb and lower-limb functional scores, quality of life, physical well-being, preference-based health measures and the number of days off work.

Results

The clinical outcomes of soft tissue injury treated by ESPs and ENPs in the ED were equivalent to routine care provided by doctors.

Conclusions

As all groups were clinically equivalent it is other factors such as cost, workforce sustainability, service provision and skill mix that become important. This result validates the role of the ENP, which is becoming established as an integral part of minor injuries care, and demonstrates that the ESP should be considered as part of the clinical skill mix without detriment to outcomes.

ISRCTN-ISRCTN trials register number

70891354.

Keywords: Accident & Emergency Medicine, Sports Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

This study reports a randomised, pragmatic trial of equivalence comparing nurse practitioners and extended scope physiotherapists to the routine care provided by doctors managing minor injuries in the emergency department.

Key messages

The study demonstrated that all clinical outcomes were equivalent to routine care, with the exception of functional recovery at 2 weeks where some uncertainty persists.

As all groups were clinically equivalent it is other factors such as cost, workforce sustainability, service provision and skill mix that become important.

This study validates the role of the nurse practitioner, which is becoming increasingly established as an integral component of minor injuries care, and also demonstrates that extended scope physiotherapists may be considered for inclusion in the skill mix managing this patient group.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The follow-up period was focused on the first 8 weeks after injury and there may still be important longer-term issues that have been overlooked.

The research was undertaken at a single centre and therefore unlikely to be representative of all UK emergency department patients; further multicentre work is required.

Since the number of practitioners was small, particularly in the ESP group, it is not clear to what extent the findings can be generalised to all ENPs and ESPs working in the ED, and confirmation of these findings in additional settings would be valuable.

Introduction

Nurses and allied health professionals (AHPs) are increasingly adopting new roles within the National Health Services (NHS) in the four nations of the UK, adapting previous skills and utilising proactive education programmes to expand their scope of practice.1 The framework for this expansion has been set out in several government papers.2–5 The proliferation of these new roles and the speed of change have made evaluation difficult,6 but it remains essential to establish who has the competencies needed to achieve high-quality outcomes in a cost-effective manner.3 7

Emergency departments (EDs) are currently a main provider of treatment for minor injuries, and annual attendances are expected to increase.8 Emergency nurse practitioners (ENPs) are senior nurses with additional training to autonomously assess, diagnose and treat patients with selected urgent conditions, particularly minor illness and injury. ENPs are being increasingly employed in minor injuries care, and are considered as an important part of future service delivery.8 9 Recently extended scope physiotherapists (ESPs) have also been developed to undertake similar extended roles, including minor injuries care, but this opportunity has not been widely adopted or evaluated.10 11

The UK College of Emergency Medicine estimates that 25% of all patients attending EDs could be managed by ENPs. It also recognises the need to utilise extensions in roles due to the increased patient demand and reduced availability of doctors that has followed recent changes in out-of-hours care provision, junior doctor training programmes (particularly reduced working hours) and national throughput standards. The use of nurses and AHPs in extended roles will therefore make a significant contribution to future minor injuries care.2 4 5 12–14

A recent literature review concluded that there is very little clinical and cost effectiveness research into the role of ENPs and ESPs within minor injuries care.15 There is already evidence demonstrating the safety and appropriateness of care by ENPs and to a lesser degree ESPs in EDs11 15–38 but few studies have investigated clinical outcomes.25 27 39 No research studies were found evaluating the clinical outcomes of minor injuries management provided by ENPs and ESPs in comparison with the routine care provided by doctors.

There is a clear need to obtain robust data on the clinical and cost effectiveness of new professional roles,40 thereby facilitating evidence-based commissioning and skill mix development. When evaluating the effectiveness of new professional groups it is important to ascertain if they are at least equivalent to existing care. For this reason, trial of equivalence methodology was employed. The research aimed to establish the clinical and cost effectiveness of three different healthcare professionals who independently manage minor injuries within UK EDs. This account describes the clinical effectiveness data: cost effectiveness is considered in a companion paper.

Method

This was a randomised, pragmatic trial of equivalence carried out in the inner city ED of University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust. The aim was to evaluate and compare the clinical outcomes of the treatment of soft tissue injury by three groups of emergency care professionals; ENPs, ESPs and doctors. The primary hypothesis was: the clinical outcome of adult patients presenting to the ED with a soft tissue injury is not the same between different healthcare practitioners. The primary alternative hypothesis was: the clinical outcome of adult patients presenting to the ED with a soft tissue injury is the same regardless of which healthcare practitioner treats them.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Trial participants were adults (older than 16 years) presenting to the ED with a peripheral soft tissue injury who were eligible for management by all the three professional groups. Soft tissue injury was defined as a traumatic peripheral musculoskeletal injury less than 72 h old with no associated bone fracture, ongoing prior injury or systemic disease/disorder. Patients were excluded if they had any of the following: dislocated joints; recent surgery; unable to give informed consent (eg, dementia), open wounds; major deformities; opiate analgesia required; concurrent chest/rib injury; neurovascular deficits and associated fracture. The exact number of people with sport and general soft tissue injuries attending EDs is not known, but it is estimated to account for 10–15% of all attendances.37 As approximately 16 million patients attend UK EDs on an annual basis8 this represents almost 2.5 million patients.

Recruitment and randomisation

Patients were recruited consecutively during fixed time periods in the participating ED. Recruitment took place between October 2006 and December 2007 on Mondays, Tuesdays and occasionally Thursdays between 08:30 and 17:00. These days were chosen because they were the only times when the ESP service was running in the ED. Shortly after arrival in the ED patients were provided with a written information sheet and invited to participate. Those agreeing were assessed by a researcher who obtained written consent and baseline data. Patients were then randomised using independently prepared and consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes. Block randomisation was used, with a block size of 12, allocating patients 1:1:1 into the three treatment arms: doctor (of any grade), ENP or ESP. Randomisation, patient recruitment and baseline assessments were completed away from the treatment area and did not influence the day-to-day running of the ED.

Intervention

The allocated healthcare professional assessed and treated the patient according to their usual practice in the ED setting. All professionals were independently managing patients from arrival through to discharge. This is consistent with the ENP role in the NHS but the ESP role is currently developing in this capacity. The efficacy of the reference treatment in this trial (doctors of all grades managing acute soft tissue injuries) has not previously been established. Once the consultation had concluded the treating practitioner completed a brief exit questionnaire to collect treatment and process measures. The researcher was blinded to the treatment allocation and had no role in any intervention. No attempt was made to blind either the patient or treating healthcare professional thus capturing any influences this interaction may have in the real-life clinical setting. There were no changes to the clinical processes or environment during the trial.

Follow-up

Participants were contacted 14 days after their ED attendance and interviewed by telephone. If no contact was possible at day 14 then the researcher attempted to contact the patient on subsequent days. If no contact was made within 5 days no further attempts were made. Participants were re-interviewed by telephone after a further 6 weeks had elapsed (8 weeks after their original ED attendance).

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was functional recovery. This was assessed using the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand score (DASH) for upper-extremity injuries,41–46 and the Lower Extremity Functional Score (LEFS) for lower-extremity injuries.47–49 These tools were used to calculate the percentage return to normal function. Secondary outcome measures were quality of life assessed using the Short Form-12v2 (SF-12v2),48 50–56 and preference-based health utility scores using the Short Form-6D (SF-6D).57 58 All these outcome measures have known minimum important clinical differences (MID) to enable equivalence to be assessed.47 48 56 58–60 The MIDs have been included in tables 2 and 3. The number of days for which the patient was unable to work was also recorded, along with self-reported recovery. Additional secondary outcomes were the time spent with each healthcare practitioner, the frequency with which various treatments and drugs were used and subsequent contact with other healthcare providers.

Table 2.

Results for primary outcome of functional recovery (intention-to-treat analysis)

| Outcome-functional recovery | Doctors 95% CIs | ESPs 95% CIs | ENPs 95% CIs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage improvement in function at 2 weeks (MID=9) | 38.3 to 58.5 (47.9) (n=80) | 35.5 to 46.6 (42.9) (n=70) | 36.0 to 47.8 (46.25) (n=73) |

| Percentage improvement in function at 8 weeks (MID=9) | 45 to 80 (63.3) (n=68) | 52.5 to 65.0 (59.2) (n=72) | 55.0 to 66.3 (60) (n=73) |

ENP, emergency nurse practitioner; ESP, extended scope physiotherapists, MID, minimum important clinical differences.

Table 3.

Results for the secondary outcomes of the SF-12, SF-6 and number of days unable to work (intention to treat analysis)

| Outcome measure | Doctors 95% CIs | ESPs 95% CIs | ENPs 95% CIs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical component of SF-12 at 2 weeks (MID=5) | 1.9 to 16.4 (9.1) (n=80) | 6.9 to 12.3 (9.4) (n=70) | 6.9 to 12.3 (9.6) (n=73) |

| Physical component of SF-12 at 8 weeks (MID=5) | −3.8 to 10.1 (3.2) (n=68) | 0.2 to 4.6 (2.4) (n=72) | 1.6 to 6.5 (4.1) (n=73) |

| SF-6D percentage recovery to preinjury levels at 8 weeks (MID=5) | 86.2 to 105.8 (92.2) (n=68) | 93.2 to 100 (94.3) (n=72) | 87.8 to 99.5 (92.2) (n=73) |

| Number of days off work at 8 weeks (MID=5) | 0.0 to 6.0 (n=68) | 0.75 to 2.0 (n=72) | 1.0 to 2.5 (n=73) |

ENP, emergency nurse practitioner; ESP, extended scope physiotherapists; MID, minimum important clinical differences; SF-6D, Short Form-6D.

Statistical methods

In accordance with recommended practice for trials of equivalence the sample size was calculated using equivalence margins rather than probability levels.61 62 The equivalence margins were calculated using the smallest minimum clinical important difference from all the outcome measures which was a difference of five.47 48 56 58–60 The trial used 90% power and the sample size required in each group was 70. Allowing for a dropout rate of 30%, and to ensure that the minimum sample size was comfortably achieved, a target of 300 patients was established (100 to be treated by each professional group). Baseline characteristics were summarised by the randomisation group, with summary measures presented as mean and SD for continuous normally distributed variables, medians and IQRs for non-normally distributed variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Analysis of variance was used to analyse the primary outcome where the sample distributions were normally distributed, with a non-parametric bootstrapping technique where non-normally distributed. For the secondary outcomes, descriptive statistics were reported and Pearson's and χ2 test used were appropriate. All statistical tests were two-sided with CIs presented as appropriate. Data were analysed using SSPS V.15 and STATA V.9 software. The main analysis was an intention-to-treat analysis and a perprotocol analysis was also undertaken.61–70 A multiple imputation technique was used to manage the missing data with IBM SSPS 19 software and eight separate imputations were performed.

Results

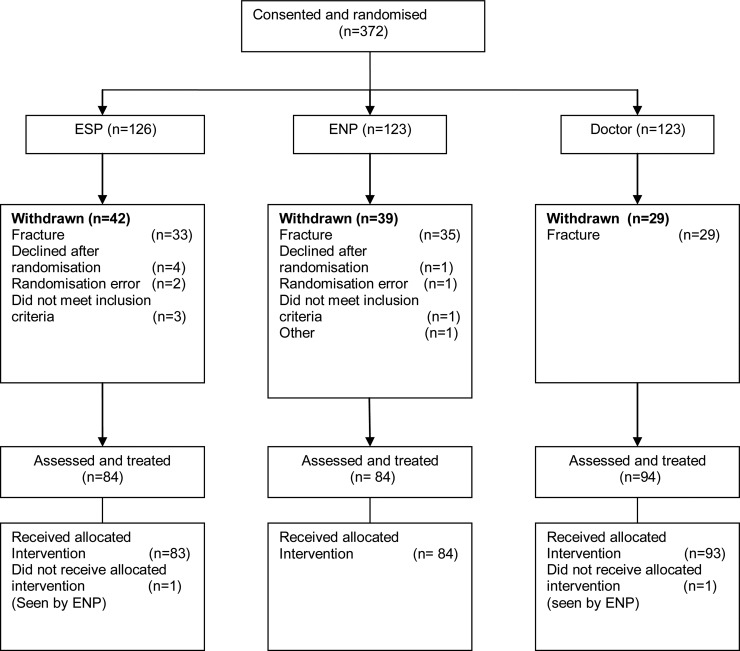

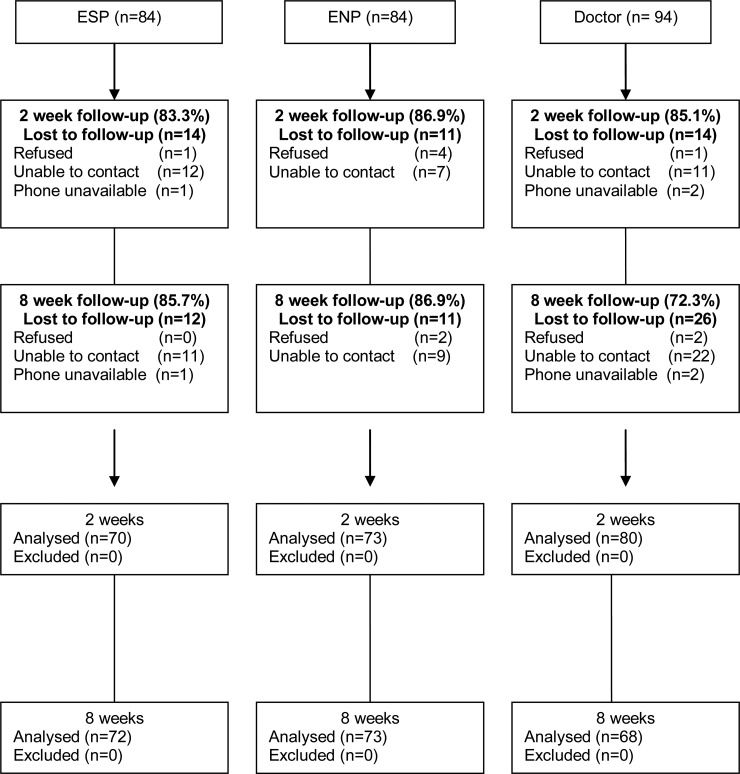

In total, 372 patients provided consent and were randomised into the trial. The number of patients who were approached but declined to participate in the trial is unknown. A CONSORT diagram is provided in figure 1, and the baseline characteristics of the recruited patients are summarised in table 1. There were no significant differences in patient characteristics between the three treatment groups in relation to injury, age, occupation and initial pain levels. However, the number of each type of injury was too small to allow statistical analysis of between-group differences. The distribution of injury type in patients was similar between the professional groups with the exception of knee, ankle and finger injuries. There were more ankle injuries in the doctor group (n=42) compared to the ESP (n=22) and ENP groups (n=23) and the ESP group had more knee and finger injuries. Patient follow-up rates are shown in figure 2: at 8 weeks these exceeded 85%, except for the doctor group where 72.3% follow-up was achieved.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing trial flow: (A) The number of patients approached, but who declined to participate is not known. (B) Patient follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all recruited patients

| Professional group | Statistical difference between groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristic | Doctor % (N) | ESP % (N) | ENP % (N) | |

| Injury type | p=0.10 | |||

| Lower limb | 71.0 (65) | 55.4 (46) | 61.4 (51) | |

| Upper limb | 29.0 (27) | 44.6 (37) | 38.6 (32) | |

| Gender | p=0.11 | |||

| Male | 61.3 (57) | 60.2 (50) | 47.0 (39) | |

| Female | 38.7 (36) | 39.8 (=33) | 53.0 (44) | |

| Age (years) | p=0.76 | |||

| 17–24 | 28.4 (25) | 30.0 (24) | 41.0 (32) | |

| 25–34 | 39.8 (35) | 35.0 (28) | 21.8 (17) | |

| 35–44 | 18.2 (16) | 18.8 (15) | 23.1 (18) | |

| 45–54 | 6.8 (6) | 6.3 (5) | 5.1 (4) | |

| 55–64 | 3.4 (3) | 5.0 (4) | 5.1 (4) | |

| 65–74 | 1.1 (1) | 1.3 (1) | 1.3 (1) | |

| 75–84 | 2.3 (2) | 3.6 (3) | 2.6 (2) | |

| Occupation | p=2.71 | |||

| Professional | 19.7 (13) | 19.7 (14) | 14.3 (10) | |

| Managerial | 28.8 (19) | 12.7 (9) | 22.9 (16) | |

| Manual | 30.3 (20) | 38.0 (27) | 41.4 (29) | |

| Not working | 21.2 (14) | 29.6 (21) | 21.4 (15) | |

| Doctors score (95% CIs) | ESP score (95% CI) | ENP score (95% CI) | Statistical difference between groups | |

| Base line pain visual analogue scale (VAS) score | 6.42 (5.68 to 7.15) | 6.67 (5.93 to 7.40) | 6.03 (5.28 to 6.77) | p=0.469 |

ENP, emergency nurse practitioner; ESP, extended scope physiotherapists.

Figure 2.

Results of the equivalence trial for the percentage improvement in function at 8 weeks.

Primary outcome

Results for the primary outcome of functional recovery are shown in figure 2 and table 2. ENPs and ESPs had equivalent outcomes to routine care provided by doctors of all grades at 8 weeks postinjury. This was consistent in a sensitivity analysis comparing ENPs and ESPs to both junior and senior grade doctors. At 2 weeks postinjury the findings are less clear cut as neither the ENP nor the ESP group outcomes are superior to routine care by doctors, but the results indicate compatibility with clinical equivalence or a worse outcome in functional recovery at this stage. No difference in the primary or secondary results was found during the multiple imputations or perprotocol analysis.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life, health utility scores and number of days unable to work are shown in table 3. ENPs and ESPs were equivalent to routine care provided by doctors in all measures. There were no significant differences in the rates of self-reported recovery at 2 and 8 weeks: almost half of all patients reported that they had completely recovered at 8 weeks, and almost 90% were completely or a lot better.

Doctors spent 25 min or less with all patients. In total 51.7% of patients seen by a doctor had their consultation completed in 0–10 min, with a further 33.3% in 10–15 min. Patients seen by an ENP had similar time profiles, except that some had 25–60 min of healthcare practitioner contact. The ESP group was different, with very few contacts being less than 10 min: most (81.9%) were between 10 and 25 min.

Medication was administered to 23.5% of all participants. There was a statistically significant difference between the treatment groups (Pearson's χ2 p<0.001), with the ESP group administering medication to 3.6% of patients compared to 23.2% for ENPs and 42.2% for doctors. There were small variations in the administration of various treatments, but the numbers in each group were small, precluding further statistical analysis.

Overall 13.2% of participants attended an appointment with their general practitioner (GP) in the first 2 weeks following injury, and 19.1% within 8 weeks. The majority of these visits (40%) were to obtain work certification relating to the injury (sick note/fit note). In the ENP group 26.4% of patients sought further GP care compared to 17.4% in the ESP group and 13.2% in the doctor group.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

This research has for the first time reported a randomised, pragmatic trial of equivalence comparing doctors, ENPs and ESPs managing minor injuries in the ED. We have demonstrated that all clinical outcomes were equivalent to routine care, with the exception of functional recovery at 2 weeks where some uncertainty persists. A substantial number of patients attended their GP for further medical attention and work certification after leaving the ED, particularly those who had seen an ENP; however, the cause of this variation is unclear.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study provides valuable clinical effectiveness data comparing different professional groups, which can be used as the basis for decisions relating to workforce and service organisation. Follow-up rates can be poor in ED-based research,11 15 36 and although we endeavoured to achieve rates in excess of 90% this was not realised, particularly in the doctor group. The cause of the lower follow-up in the doctor group is unclear and may be due to chance variation. It is possible that patients treated by doctors were more or less recovered or satisfied with their care, and therefore less likely to participate in follow-up. The number of patients who were approached but declined to enter the trial is unknown as it proved impossible to accurately collect this information in the pressured clinical environment of the study setting.

We were able to capture detail of the first 8 weeks following injury, but have no data on longer-term recovery. It is encouraging that by 8 weeks 86.6% of patients were ‘a lot better’ or ‘completely better’, but there may still be important longer-term issues that we have overlooked. The research was undertaken at a single centre and therefore unlikely to be representative of all UK ED patients; further multicentre work is required. Since the number of practitioners was small, particularly in the ESP group, it is not clear to what extent the findings can be generalised to all ENPs and ESPs working in the ED, and confirmation of these findings in additional settings would be valuable. We confined the research to acute peripheral musculoskeletal soft tissue injury, and are therefore unable to comment on the effectiveness of ENPs and ESPs when managing other conditions, including fractures. Finally, the primary outcome measures have been validated, but not in the population recruited to this study. The DASH and LEFS were chosen because they provided the best ‘fit’ at the time, but future research is needed to develop outcome measures in this area.

Comparison to other studies

There is only one comparable study: a non inferiority trial comparing ESPs to routine care provided by ENPs and doctors together.11 15 36 This study recruited a slightly broader patient population (including fractures and spinal injuries) and concluded that there was weak evidence that the ESP group may be inferior to routine care in the time taken to return to normal activities (p=0.071). The ESP was equivalent or superior to routine care in patient satisfaction and there were no significant differences in return to work, pain or health scores at 6 months postinjury, although the ESP did obtain a worse health assessment questionnaire response at 3 months postinjury (p=0.048). It is not clear why the results of this study are different to ours, but it is most likely to be related to the patient population and outcome measures, as well as potential variation in the clinicians involved.

Study implications

This study validates the role of the ENP, which is becoming increasingly established as an integral component of minor injuries care, and also demonstrates that the ESP could be considered for inclusion in the usual skill mix managing this patient group. It also provides important information regarding the current routine provision of care by doctors, demonstrating that this professional group continues to represent the ‘gold standard’. As all groups were found to be clinically equivalent it is other factors such as cost, workforce sustainability, service provision and skill mix that become important. This research has not set out to establish the optimum still mix required, but will assist in strategic decision-making.

Future research

While the clinical effectiveness of the different healthcare professionals has been examined and compared, the factors that influence our results remain unclear. It is difficult to identify which components of the complex interaction between professionals and patients are responsible for any particular effect. It is possible that different professionals are obtaining equivalent outcomes for different reasons, or even that all three healthcare professionals are equally ineffective with equivalence attributable solely to the effects of natural soft tissue healing; however, the use of an untreated control group would not be ethically acceptable. It would be valuable to repeat this research in other settings and with broader inclusion criteria, and to explore why the frequency of subsequent GP consultation varies between practitioners despite the fact that clinical outcomes are the same. Finally, cost effectiveness is an important consideration, and is described in a companion paper.

Conclusion

Over the past decade the transformation of emergency care and the development of new roles within the NHS have been profound. This research indicates that both nurses and physiotherapists with extended skills can successfully manage patients with uncomplicated soft tissue injury, achieving clinical outcomes that are equivalent to routine care by a doctor.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Carey McClellan (CM) initiated the project with input to design and development from Fiona Cramp (FC), Jane Powell (JP) and Jonathan Benger (JB). CM collected the data and undertook initial analysis with supervision and additional input from FC, JP and JB. CM drafted the manuscript which was then revised and approved by FC, JP and JB. CM acts as guarantor.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) CM, FC, JP and JB have support from The University of the West of England for the submitted work; (2) CM, FC,JP and JB have no relationships with The University of the West of England that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and (4) CM, FC,JP and JB have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Funding: The research was funded under a PhD bursary from The University of the West of England. Funded by The University of the West of England.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained by: (1) The Salisbury and South Wiltshire Ethics Committee, obtained on the 4th May 2006 (ref: 06/Q2008/10); (2) The Faculty of Health and Social Care Ethics Committee at the University of the West of England, obtained on the 10th of July 2006 (ref: HSC/06/07/57).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.8jf11.

References

- 1.Leaman AM. See and treat: a management driven method of achieving targets or a tool for better patient care? One size does not fit all. Emerg Med J 2003;20:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The NHS plan-A plan for investment A plan for reform. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/Publications PolicyAndGuidance/DH_4002960 (accessed 20 Feb 2008).

- 3.Department Of Health Freedom to practise: dispelling the myths. London: Department of Health, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department Of Health Transforming emergency care in England—a report by professor sir George Alberti. England, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health The Chief Health Professions Officer's Ten Roles for Allield Health Professionals. 2004

- 6.Lattimer V, Burgess A, Jamieson K, et al. A review of urgent care literature published between 2001–2006. University of Southampton, Southampton, UK: School of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine, Health and Life Sciences, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alberti KGMM. Emergency care 10 years on: reforming emergency care. London: Department of Health, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8.The College of Emergency Medicine The Way Ahead 2008–2012. Statagy and guidance for Emergency Medicine in the UK and the Republic of Ireland. London, UK: The College of Emergency Medicine, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.The College of Emergency Medicine Way ahead. London: The College of Emergency Medicine, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paw RC. Emergency department staffing in England and Wales, April 2007. Emerg Med J 2008;25:420–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClellan CM, Greenwood R, Benger JR. Extended scope physiotherapists in the emergency department: what do patients think? Emerg Med J 2006;25:384–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health Reforming emergency care. 2001

- 13.Department Of Health Direction of travel: a discussion document. London: Department Of Health, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. 2008

- 15.McClellan CM, Cramp F, Powell J, et al. Extended scope physiotherapists in the emergency department: a literature review. Phys Therapy Rev 2010;15:106–11 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarvis M. Satisfaction guaranteed? Emerg Nurse 2007;14:34–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGee LA, Kaplan L. Factors influencing the decision to use nurse practitioners in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2007;33:441–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thrasher C, Purc-Stephenson RJ. Integrating nurse practitioners into Canadian emergency departments: a qualitative study of barriers and recommendations. CJEM 2007;9:275–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moser MS, Abu-Laban RB, Van Beek CA. Attitude of emergency department patients with minor problems to being treated by a nurse practitioner. Can J Emerg Med 2004;6:246–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter AJE, Chochinov AH. A systematic review of the impact of nurse practitioners on cost, quality of care, satisfaction and wait times in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med 2007;9:286–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barr M. Patient satisfaction with a new nurse practitioner service. Accid Emerg Nurs (serial online) 2000;8:144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allerston J, Justham D. Nurse practitioners and the Ottawa Ankle Rules: comparisons with medical staff in requesting X-rays for ankle injured patients. Accid Emerg Nurs 2000;8:110–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Considine J, Martin R, Smit D, et al. Defining the scope of practice of the emergency nurse practitioner role in a metropolitan emergency department. Int J Nurs Pract 2006;12:205–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Considine J, Martin R, Smit D, et al. Emergency nurse practitioner care and emergency department patient flow: case-control study. Emerg Med Australas 2006;18:385–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper MA, Lindsay GM, Kinn S, et al. Evaluating Emergency Nurse Practitioner services: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2002;40:721–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tachakra S, Deboo P. Comparing performance of ENPs and SHOs. (Research comparing emergency nurse practitioners and senior house officers. 12 refs). Emerg Nurse 2001;9:36–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakr M, Angus J, Perrin J. Care of minor injuries by emergency nurse practitioners or junior doctors: a randomised controlled trial (Research in Sheffield. 10 refs). Lancet 1999;354:1321–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang E, Daly J, Hawkins A, et al. An evaluation of the nurse practitioner role in a major rural emergency department. J Adv Nurs 1999;30:260–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meek S, Kendall K, Porter J. Can accident and emergency nurse practitioners interpret radiographs? A multicentre study (Research. 5 refs). J Accid Emerg Med 1998;15:105–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meek SJ, Ruffles G, Anderson J, et al. Nurse practitioners in major accident and emergency departments: a national survey. J Accid Emerg Med 1995;12:177–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann CJ, Grant I, Guly H, et al. Use of the Ottawa ankle rules by nurse practitioners. J Accid Emerg Med 1998;15:315–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Overton-Brown P, Anthony D. Towards a partnership in care: nurses’ and doctors’ interpretation of extremity trauma radiology. J Adv Nurs 1998;27:890–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhee KJ, Dermyer AL. Patient satisfaction with a nurse practitioner in a university emergency service. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:130–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powers MJ, Jalowiec A, Reichelt PA. Nurse practitioner and physician care compared for nonurgent emergency room patients. Nurse Pract 1984;42:44–5 passim; Feb;9(2):39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ball ST, Walton K, Hawes S. Do emergency department physiotherapy practitioner's, emergency nurse practitioners and doctors investigate, treat and refer patients with closed musculoskeletal injuries differently? Emerg Med J 2007;24:185–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson B, Shepstone L, Poland F, et al. Randomised controlled trial and cost consequences study comparing initial physiotherapy assessment and management with routine practice for selected patients in an accident and emergency department of an acute hospital. Emerg Med J 2005;22:87–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McClellan CM, Greenwood R, Benger JR. A study into the impact of an extended scope physiotherapist on: waiting times, patient satisfaction and long-term outcomes from soft tissue ankle injuries in an emergency department. Bristol, UK: University Hospitals Bristol Foundation NHS trusts. Report, 2005

- 38.Anaf S, Sheppard LA. Physiotherapy as a clinical service in emergency departments: a narrative review. Physiotherapy 2007;93:243–52 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardstone B, Shepstone L, Poland F. Randomised controlled trial and cost consequences study comparing initial physiotherapy assessment and management with routine practice for selected patients in an accident and emergency department of an acute hospital. Emerg Med J 2005;22:87–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Department of Health Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS. London: Department Of health, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AH, et al. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther 2001;14:128–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.SooHoo NF, McDonald AP, Seiler JG, III, et al. Evaluation of the construct validity of the DASH questionnaire by correlation to the SF-36. J Hand Surg 2002;27:537–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McClure PML. Meaures of adult shoulder function. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:S50–8 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bot SD, Terwee CB, van der Windt DA, et al. Clinimetric evaluation of shoulder disability questionnaires: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:335–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jester A, Harth A, Germann G. Measuring levels of upper-extremity disability in employed adults using the DASH questionnaire. J Hand Surg 2005;30:1074.e1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jester A, Harth A, Wind G, et al. Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire: Determining functional activity profiles in patients with upper extremity disorders. J Hand Surg 2005;30:23–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, et al. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network. Phys Ther 1999;79:371–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alcock GK, Stratford PW. Validation of the lower extremity functional scale on athletic subjects with ankle sprains. Physiother Can 2002;54:233–40 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watson CJ, Propps M, Ratner J, et al. Reliability and responsiveness of the lower extremity functional scale and the anterior knee pain scale in patients with anterior knee pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2005;35:136–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perkins JJ, Sanson-Fisher RW. An examination of self- and telephone-administered modes of administration for the Australian SF-36. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:969–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ware JEJ. SF-36 health survey update. Spine 2000;25:3130–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ware JE, Kosinski M. Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: a response. Qual Life Res 2001; discussion 415–20;10:405–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, et al. New England Medical Center Hospital. Health Assessment Lab. How to score V.2 of the SF-12 health survey (with a supplement documenting V.1). Lincoln, R.I.; Boston, MA: QualityMetric Inc., Health Assessment Lab, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kirkley A, Griffin S. Development of disease-specific quality of life measurement tools. Arthroscopy 2003;19:1121–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beaton DE, Schemitsch E. Measures of health-related quality of life and physical function. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;90–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ware JE. User's manual for the SF-36v2 health survey. London: Quality Metric, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care 2004;42:851–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walters SJ, Brazier JE. Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res 2005;14:1523–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gummesson C, Atroshi I, Ekdah C. The disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) questionnaire: longditudinal construct and self related health change after surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003;4:4–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmitt JS, Di Fabio R. Reliable change and minimum important difference (MID) proportions facilitated group responsiveness comparisons using individual threshold criteria. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:1008–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones B, Jarvis P, Lewis JA, et al. Trials to assess equivalence: The importance of rigorous methods. Br Med J 1996;313:36–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Le Henanff A, Giravdeau B, Baron G, et al. Quality of reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials. JAMA 2006;295:1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hauck WW, Anderson S. Some issues in the design and analysis of equivalence trials. Drug Infom J 1999;33:109–118 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Irving KH, Toshihiko M. Design issues in noninferiority/equivalence trials. Drug Infom J 1999;33:1205–18 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seigle jP. Equivalence and noninferiority trails. Am Heart J 2000;139:166–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carneiro av. Ensaios de Equivalencia entre Medicamentos:Aspectos Metodologicos. Rev Port Cardiol 2003;22:1125–3914655314 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gomberg-Maitland M, Frison L, Halperin JL. Active-control clinical trials to establish equivalence or noninferiority: methodological and statistical concepts linked to quality. Am Heart J 2003;146:398–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wojdyla D. Cluster randomisation trials and trials of equivalence. Presented at UNDP/UNFPA/WHO World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research training in Human Reproduction. The World Health Organization, 2005

- 69.Gotzsche PC. Lessons from and cautions about noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials. JAMA 2006;295:1172–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Piaggio G. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 2006;295:1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.