Case Reports

Patient #1

A 22-year-old African American male presented with abdominal pain and coffee ground vomitus after allegedly swallowing a pocketknife. The patient had been feeling depressed and had run out of his medications (duloxetine hydrochloride [Cymbalta][Lilly] and haloperidol) prior to the foreign body ingestion. His psychiatric history included major depression, borderline personality disorder, and bipolar disorder.

The patient underwent an upper endoscopy for removal of the object (Figures 1–3). The endoscope was inserted, and the pocketknife was found in the stomach. A snare was placed around the pocketknife and then closed. The pocketknife and endoscope were then carefully withdrawn together. There was no obvious trauma from the procedure.

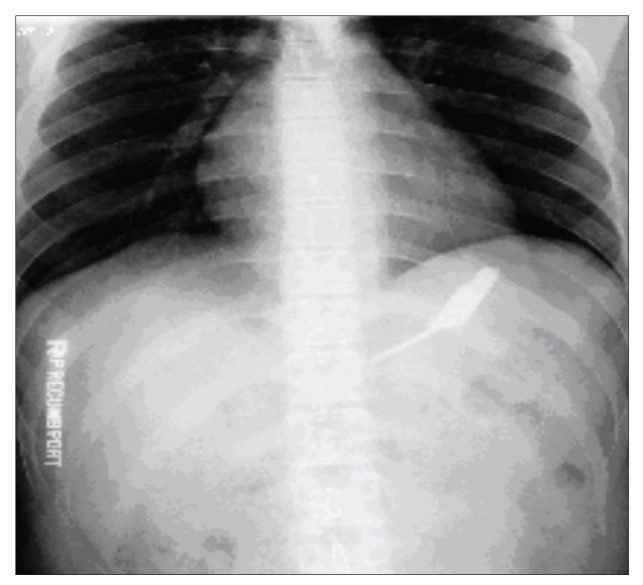

Figure 1.

An abdominal radiograph showing a pocketknife in the patient's stomach.

Figure 3.

The retrieved pocketknife.

The patient had had a similar presentation 3 weeks earlier when he had ingested 3 screws and 1 blade. At that time, he underwent an upper endoscopy for removal of the objects, which were lodged in his stomach. Since 2007, the patient has undergone 9 upper endoscopies and 2 colono-scopies at our institution as well as many more procedures at other hospitals. The patient has swallowed forks, bolts, screws, blades, steak knife blades, and pocketknives. He has also undergone multiple laparotomies for the management of foreign body ingestion since 13 years of age.

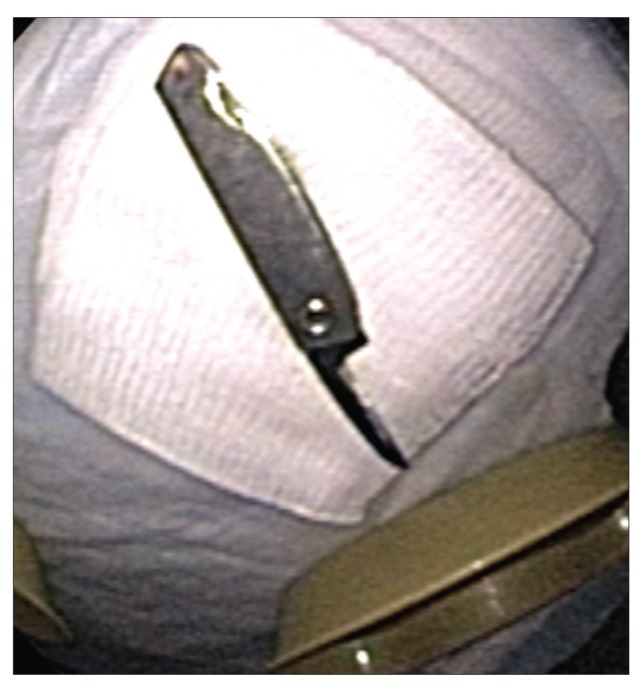

Figure 2.

Endoscopic view of the pocketknife being retrieved with a snare.

Patient #2

A 25-year-old African American female presented after swallowing a ballpoint pen (Figures 4 and 5). An upper endoscopy showed a ballpoint pen in the distal esophagus, with the pointed end lodged proximally at 35 cm from the incisors. The pen was grasped with forceps and removed with the assistance of an overtube. The patient had multiple psychiatric disorders, including borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, bulimia nervosa, post-traumatic stress disorder, and pica.

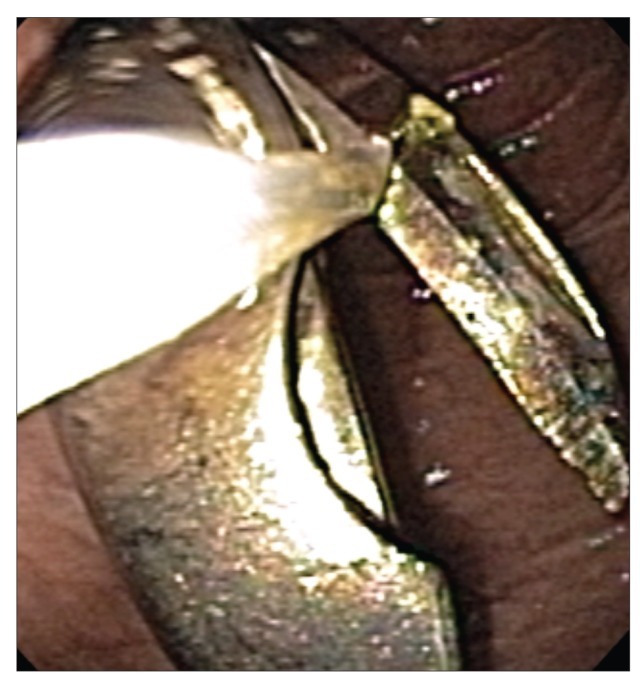

Figure 4.

Endoscopic view of the ballpoint pen found in the patient's distal esophagus.

Figure 5.

The retrieved ballpoint pen.

The patient has had numerous episodes of compulsive foreign body ingestion since 5 years of age. Since 2004, she has undergone 64 upper endoscopies and 4 colonoscopies at our institution and many more procedures at other hospitals. She has also undergone multiple laparotomies for the management of foreign body ingestion.

Discussion

Intentional foreign body ingestion is challenging to treat for emergency room physicians, gastroenterologists, and psychiatrists. The time since ingestion and type of ingested object are often unclear on presentation, making it difficult for endoscopists to determine the optimal timing of upper endoscopy and the type of anesthesia necessary for the procedure. Gitlin and colleagues divided the behavior of these patients into 4 distinct diagnostic subgroups: malingering, psychosis, pica, and personality disorder.1 Both of our patients had diagnoses of borderline personality disorder in addition to an Axis I disorder, such as major depressive disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder.

Self-injurious behavior is fairly common in patients with severe personality disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and some psychotic disorders.2 These patients often have histories of childhood deprivation, physical abuse, and/or sexual abuse.3 In patients with personality disorders, intentional ingestion is a form of self-injury. These behaviors are usually nonsuicidal and are considered to be parasuicidal in intent (ie, the ingestion is not done with the intention to die but due to a number of other psychological processes).1 Self-injury can be an expression of rage toward oneself and/or caregivers, punishment for oneself and/or others, or a way to force others to provide care. Unlike other self-injurious behaviors, ingestion involves an element of secretiveness and control, as the ingestion is not overt to the naked eye. It is interesting to note the countertransference anger that the medical staff often experiences toward such patients, reflecting their sense of powerlessness and their feeling of being controlled by the patient. The patient may feel empowered by being able to frustrate and challenge his or her doctors and may therefore be motivated to indulge in additional ingestions.

In a study of intentional swallowing of foreign bodies conducted at Rhode Island Hospital, Huang and associates found that 33 patients were responsible for 305 cases of intentional ingestion over an 8-year period (2001—2009).4 Ten percent of these patients were in prisons, 32% were in private homes, and 58% were in institutions; 79% of all patients were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder. A variety of foreign bodies were retrieved, with the most common items being pens, batteries, knives, razor blades, metal objects, pencils, toothbrushes, spoons, and coins. The most common accessories used to extract the foreign bodies were snares (58%), rat-tooth grasping forceps (14.4%), retrieval nets (11.5%), overtubes (10.8%), and rubber hoods (4.6%). The estimated total cost to the hospital for treating these 33 patients was over $2 million.

A study by Palta and coworkers at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles reviewed 262 cases of foreign body ingestion and found that 92% of cases were intentional, 85% of cases involved psychiatric patients, and 84% of cases occurred in patients with a history of prior ingestions.5 The time from ingestion to presentation was more than 48 hours in 168 cases (64%). The overall success rate of endoscopic extraction was 90% (165/183 cases).

Flexible endoscopy is the first choice for management of this clinical emergency due to its efficacy, low morbidity, and low cost compared to surgical treatment. Management is influenced by the patient’s age and clinical condition; the size, shape, and type of the ingested object; the anatomic location of the lodged object; and the technical abilities of the endoscopist. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends urgent endoscopic intervention when a sharp object or disk battery is lodged in the esophagus; in addition, urgent endoscopy is recommended to prevent aspiration when an ingested foreign object or food bolus impaction creates a high-grade obstruction and the patient is unable to manage his or her secretions.6 For other objects in the esophagus, as well as long (>5 cm) or sharp objects in the stomach, endoscopic intervention can be delayed for 24 hours. Sharp, pointed, and long objects in the esophagus and stomach require endoscopic retrieval due to the increased risk of complications. Blunt objects that have passed into the stomach can be managed safely without endoscopy. Most objects pass through the gut within 4—6 days, although some objects may take as long as 4 weeks. While waiting for spontaneous passage of a foreign body, patients are usually instructed to continue a regular diet and to observe their stools for the ingested object. Although deaths caused by foreign body ingestion have been reported on rare occasions, mortality rates have been extremely low.7

There have been many case reports of intentional foreign body ingestion, but, unfortunately, very limited research has been conducted on appropriate treatment for foreign body ingestion in patients with borderline personality disorders. Various treatment modalities are used to treat patients with personality disorders who engage in general self-harming behaviors. Studies have shown that dialectical behavioral therapy decreases self-injury, hopelessness, and depressive features in this population.8 Supportive therapy and other cognitive behavioral therapy approaches have also been shown to be helpful.9,10 Pharmacologic interventions with agents used to treat alcohol and drug addiction (such as naltrexone and clonidine) have led to decreases in both the impulsive drive to self-harm and the frequency of self-injury, according to several studies.11,12 However, there do not appear to be any studies that have specifically examined treatment for recurrent foreign body ingestion.

Conclusion

Due to the need for potentially long hospital stays and repeat endoscopic and surgical interventions, patients with foreign body ingestion frequently utilize a large proportion of already scarce medical resources at institutions that often serve a low socioeconomic population. More prospective studies are needed to help develop better techniques for management and treatment of this unique group of patients, so that physicians can provide more efficient and effective treatment that will result in both better patient outcomes and reduced costs.

Footnotes

The authors would like to acknowledge the consent and cooperation of the patients discussed in this paper.

References

- 1.Gitlin DF, Caplan JP, Rogers MP, Avni-Barron O, Braun I, Barsky AJ. Foreign body ingestion in patients with personality disorders. chosomatics. 2007;48:162–166. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerson J, Stanley B. Suicidal and self-injurious behavior in personality disorder: controversies and treatment directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4:30–38. doi: 10.1007/s11920-002-0009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santa Mina EE, Gallop RM. Childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult self-harm and suicidal behavior: a literature review. Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43:793–800. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang BL, Rich HG, Simundson SE, Dhingana MK, Harrington C, Moss SF. Intentional swallowing of foreign bodies is a recurrent and costly problem that rarely causes endoscopy complications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:941–946. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palta R, Sahota A, Bemarki A, Salama P, Simpson N, Laine L. Foreign body ingestion: characteristics and outcomes in a lower socioeconomic population with predominantly intentional ingestion. GastrointestEndosc. 2009;69:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.072. (3 pt 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guideline for the management of ingested foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:802–806. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett DR, Baird CJ, Chan KM, et al. Zinc toxicity following massive coin ingestion. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1997;18:148–153. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199706000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koerner K, Linehan MM. Research on dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2000;23:151–167. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aviram RB, Hellerstein DJ, Gerson J, Stanley B. Adapting supportive psychotherapy for individuals with borderline personality disorder who self-injure or attempt suicide. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10:145–155. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown GK, Newman CF, Charlesworth SE, Crits-Christoph P, Beck AT. An open clinical trial of cognitive therapy for borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2004;18:257–271. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.3.257.35450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth AS, Ostroff RB, Hoffman RE. Naltrexone as a treatment for repetitive self-injurious behavior: an open-label trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Philipsen A, Richter H, Schmahl C, et al. Clonidine in acute aversive inner tension and self-injurious behavior in female patients with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1414–1419. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]