Summary

Integrin-based focal adhesions (FA) transmit anchorage and traction forces between the cell and the extracellular matrix (ECM). To gain further insight into the physical parameters of the ECM that control FA assembly and force transduction in non-migrating cells, we used fibronectin (FN) nanopatterning within a cell adhesion-resistant background to establish the threshold area of ECM ligand required for stable FA assembly and force transduction. Integrin–FN clustering and adhesive force were strongly modulated by the geometry of the nanoscale adhesive area. Individual nanoisland area, not the number of nanoislands or total adhesive area, controlled integrin–FN clustering and adhesion strength. Importantly, below an area threshold (0.11 µm2), very few integrin–FN clusters and negligible adhesive forces were generated. We then asked whether this adhesive area threshold could be modulated by intracellular pathways known to influence either adhesive force, cytoskeletal tension, or the structural link between the two. Expression of talin- or vinculin-head domains that increase integrin activation or clustering overcame this nanolimit for stable integrin–FN clustering and increased adhesive force. Inhibition of myosin contractility in cells expressing a vinculin mutant that enhances cytoskeleton–integrin coupling also restored integrin–FN clustering below the nanolimit. We conclude that the minimum area of integrin–FN clusters required for stable assembly of nanoscale FA and adhesive force transduction is not a constant; rather it has a dynamic threshold that results from an equilibrium between pathways controlling adhesive force, cytoskeletal tension, and the structural linkage that transmits these forces, allowing the balance to be tipped by factors that regulate these mechanical parameters.

Key words: Cell adhesion, Fibronectin, Vinculin, Talin, Focal adhesion

Introduction

Integrin-mediated adhesion to extracellular matrix (ECM) components such as fibronectin (FN) transmits mechanical forces and ‘outside-in’ biochemical signals regulating tissue formation, maintenance, and repair (Hynes, 2002; Danen and Sonnenberg, 2003; Wozniak and Chen, 2009). Integrin receptors regulate their affinity for ligands by undergoing conformational activation through ‘inside-out’ signaling via binding of the cytoskeletal protein talin to the β-integrin tail (Hynes, 2002; Calderwood and Ginsberg, 2003; Shattil et al., 2010). Following activation and ligand binding, integrins cluster together into nanoscale adhesive structures that function as foci for the generation of strong anchorage and traction forces in stationary and migrating cells (Balaban et al., 2001; Beningo et al., 2001; Galbraith et al., 2002; Tan et al., 2003; Gallant et al., 2005). These focal adhesion (FA) complexes consist of integrins and actins vertically separated by a ∼40 nm core that includes cytoskeletal elements, such as vinculin, talin and α-actinin, and signaling molecules, including FAK, src, and paxillin (Geiger et al., 2001; Zamir and Geiger, 2001; Kanchanawong et al., 2010). Integrin clustering is a crucial step in the adhesive process promoting recruitment of cytoskeletal components, activation of signaling molecules, and enhancing adhesive force (Miyamoto et al., 1995a; Miyamoto et al., 1995b; Maheshwari et al., 2000; Roca-Cusachs et al., 2009; Bunch, 2010; Petrie et al., 2010). These integrin-based FAs serve as mechanosensors converting environmental mechanical cues into biological signals (Geiger et al., 2009).

Two central questions in mechanobiology are: (i) what information is encoded by the physical properties of ECM molecules?, and (ii) how are these physical properties sensed and interpreted by cells as instructions to assemble a force-transmitting adhesion complex (Bershadsky et al., 2006; Vogel and Sheetz, 2006; Gardel et al., 2010; Parsons et al., 2010)? Previous work has shown that both ECM rigidity and ligand spacing influence FA and stress fiber assembly, cell spreading, migration speed, and adhesive forces (Massia and Hubbell, 1991; García et al., 1998a; Maheshwari et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2001; Coussen et al., 2002; Koo et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2003; Arnold et al., 2004; Griffin et al., 2004; Engler et al., 2006; Cavalcanti-Adam et al., 2007; Petrie et al., 2010; Selhuber-Unkel et al., 2010). For instance, different average minimal RGD ligand spacings are required for spreading (440 nm) and FA assembly (140 nm) (Massia and Hubbell, 1991). More recent studies with precisely spaced RGD ligands confirmed that FA assembly, spreading, and migration require close integrin ligand spacing (<90 nm) and showed that cells cannot integrate signals from integrin–ligand complexes spaced more than 58 nm from each other (Arnold et al., 2004; Cavalcanti-Adam et al., 2006). However, the minimal area of integrin–ligand complexes required to assemble an adhesion complex and transmit force remains unknown.

The influence of the size of adhesive complexes on force transmission has also been investigated, but a generalized relationship between FA area and force has not been established. Nascent punctate nanoscale (<0.2 µm2) FAs assemble at the tips of filopodia and the leading edges of lamellipodia (Fig. 1A) in an actin polymerization-dependent but myosin-II-independent process to transmit traction forces (Beningo et al., 2001; Cai et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2008; Stricker et al., 2011). These nascent adhesions either undergo rapid turnover within the lamellipodium or mature into larger, elongated FAs under the influence of myosin-dependent cytoskeletal tension (Chrzanowska-Wodnicka and Burridge, 1996; Riveline et al., 2001; Cai et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2008; Gardel et al., 2008). Mature, large (1.0–10 µm2) FAs (Fig. 1A) anchor cells to the substrate to maintain cell morphology and tensional homeostasis (Balaban et al., 2001; Beningo et al., 2001; Tan et al., 2003). Using deformable substrates and traction force microscopy, a linear relationship between FA area and traction force was reported for large (>1 µm) FAs, indicating a constant traction stress at these adhesive structures (Balaban et al., 2001; Tan et al., 2003). However, other studies have measured widely variable adhesive forces versus FA area for FAs (Beningo et al., 2001; Goffin et al., 2006; Stricker et al., 2011). Recently, Gardel and colleagues elegantly demonstrated a strong correlation between FA size and traction force only during the initial stages of FA maturation and growth, whereas mature adhesions did not exhibit this relationship (Stricker et al., 2011). Moreover, this group found a spatial dependence for traction forces across an entire cell with higher traction forces transmitted by mature FAs near the cell periphery. Together, these studies show that FA function (i.e. force transmission) is not reliably predicted by FA size.

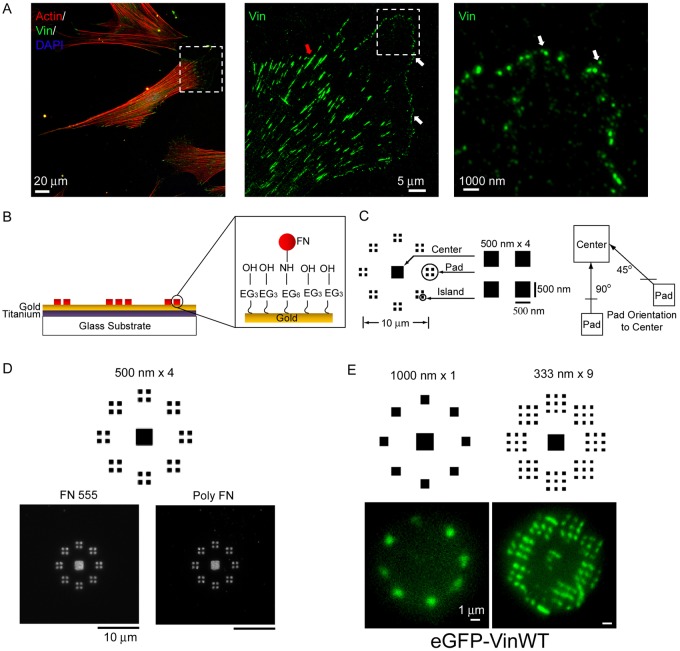

Fig. 1.

Cells adhere to nanopatterned FN and form adhesive structures. (A) Nanoscale nascent adhesions (vinculin) formed at the lamellipodium and leading edge of a fibroblast (mature adhesions: red arrowhead; nascent adhesions: white arrowhead). (B) FN patterns on PDMS stamps are transferred onto the substrates with NHS esters resulting in the transfer and tethering of FN molecules onto the substrate. (C) Adhesive zone of nanoislands (500 nm×4 shown); each zone consists of a center square (2×2 µm) surrounded by eight radially distributed adhesion pads. Each adhesion pad consists of 1, 2, 4 or 9 square nanoislands. Adhesive pads are presented in two orientations (45°, 90°) relative to the center pad. (D) FN nanopatterns retain high spatial fidelity in culture as visualized by direct imaging of Alexa-Fluor-555-labeled FN (FN 555) or indirect immunostaining using a polyclonal antibody against FN (poly FN). (E) Cells expressing GFP–vinculin assemble vinculin-containing FAs on nanopatterns.

To define additional ECM physical parameters that determine adhesive complex function, we examined whether there is a minimal area of integrin–ligand complexes required to assemble an adhesive complex and transmit adhesive force. In the present study, we used novel nanopatterned adhesive arrays of FN nanoislands within a non-adhesive background to address this question. We found that stable assembly of integrin–FN clusters and generation of adhesive force depend on the area of individual adhesive nanoislands and not the number of adhesive contacts (number of nanoislands) or total adhesive area. Importantly, the minimal area of integrin–FN clusters required for FA assembly and force transmission exhibits a threshold that is not constant, but is instead regulated by recruitment of talin and vinculin and the cytoskeleton tension applied to these adhesive clusters. We propose that this dynamic area threshold for stable FA assembly and force transmission results from an equilibrium between pathways controlling adhesive force, cytoskeletal tension, and the structural linkage that transmits these forces. We further suggest that perturbation of this force equilibrium is a local regulatory mechanism for the assembly/disassembly of adhesive structures and the transmission of adhesive forces.

Results

FN nanoislands direct assembly of nanoscale adhesive clusters

To study mechanobiology responses at the scale of individual adhesive structures, we engineered cell adhesion arrays with 250–1000 nm square FN islands using modified subtractive contact printing to covalently immobilize FN into defined nanopatterns on a cell adhesion-resistant background (Coyer et al., 2011) (Fig. 1B; supplementary material Fig. S1A). Several FN nanopattern configurations were prepared to vary the nanoscale geometry in terms of nanoisland size, number, and spacing (supplementary material Fig. S2). We generated 10 µm diameter adhesive zones with a center square (2×2 µm) surrounded by 8 radially distributed adhesion pads containing nanoislands (Fig. 1C). This configuration allowed for manipulation of the adhesive nanoisland geometry independently from cell shape/spreading which was maintained constant for all nanopattern configurations. This is a critical consideration because both anchorage and traction forces are cell shape and position dependent (Gallant et al., 2005; Stricker et al., 2011). Two adhesion pad orientations (90°, 45°) relative to the center square are present in the adhesive zone. Each adhesion pad consists of 1, 2, 4 or 9 square nanoislands. These nanoislands present adhesive areas (0.06–1.0 µm2) corresponding to the size of small, nascent FAs (Beningo et al., 2001; Choi et al., 2008) and are below the size of mature FAs (1–10 µm2) (Goffin et al., 2006; Sniadecki et al., 2006). The edge-to-edge distance between nanoislands is equal to the nanoisland side dimension. Adhesive pattern geometry is designated by the length of the side of the nanoislands and number of nanoislands; for example, 500 nm×4 refers to adhesive pads with 4 nanoislands with sides of 500 nm (Fig. 1C). Printed nanoisland dimensions were confirmed by atomic force microscopy imaging (Coyer et al., 2007; Coyer et al., 2011). Adhesive zones were spaced 100 µm apart from each other in order to support adhesion of a single cell (supplementary material Fig. S1B).

NIH3T3 murine fibroblasts cultured overnight (>16 h) adhered to FN adhesive zones as single cells and remained nearly spherical (supplementary material Fig. S1B). To examine the stability and fidelity of FN nanopatterns in the presence of cells, fibroblasts were cultured overnight in serum-containing medium on patterns printed with human FN labeled with Alexa Fluor 555. Examination by fluorescence microscopy demonstrated that the printed pattern of Alexa-Fluor-555-labeled FN was retained with high-fidelity and uniform intensity (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, immunostaining with a polyclonal antibody that reacts with human, bovine and murine FN showed no changes in nanopattern integrity or intensity (Fig. 1D). No staining for FN outside the nanopatterned islands, including between nanoislands, was detected. Vinculin-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts expressing GFP–vinculin showed patterns of vinculin recruitment to FN nanoislands that corresponded to the size and location of the FN nanopatterns (Fig. 1E). These results demonstrate that the FN nanopatterns retain high fidelity in terms of spatial distribution and density in overnight culture, indicating that cells cannot lay down secreted or serum-derived FN or reorganize the printed FN on the surface.

Assembly of stable integrin–FN clusters exhibits an ECM area threshold

We first examined whether assembly of stable, steady-state integrin–FN clusters on the nanoislands is modulated by the nanoscale geometry of the adhesion interface. Clustering of ligand-bound integrins is an early step in the formation of dot-like nascent adhesions (Wiseman et al., 2004; Gardel et al., 2010). We performed integrin immunostaining using a cross-linking and detergent extraction method that selectively retains integrins bound to FN and removes non-ligated integrins (García et al., 1999; Keselowsky and García, 2005). Cells were cultured on FN nanopatterns overnight (>16 h) to allow the formation of stable integrin–FN clusters. We have previously shown that both integrin–FN complexes and adhesion strength reach stable, steady-state values after 8 hours (Gallant et al., 2005; Michael et al., 2009). Adherent cells were incubated in the cell-impermeable reagent sulfo-DTSSP to cross-link integrins to FN. Following SDS detergent extraction of cellular components, including uncross-linked integrins, immunostaining for α5 integrin was performed. Previous analyses with function-perturbing antibodies demonstrated that adhesion in the NIH3T3 cell model is primarily mediated by α5β1-integrin–FN without significant contributions from other receptors or extracellular ligands (Gallant et al., 2005).

For the present analysis, Alexa-Fluor-555-labeled FN and Alexa-Fluor-488-labeled secondary antibodies were used to simultaneously visualize FN nanoislands (red) and bound integrins (green). After screening different nanopattern configurations, we selected four adhesive zone configurations for detailed analyses of integrin recruitment and localization. Three patterns presented the same adhesive pad area (1.0 µm2) but the pad area was distributed over 1 (1000 nm×1), 4 (500 nm×4) or 9 nanoislands (333 nm×9). Because less is known about the structure/size of nascent adhesions, a pattern (250 nm×4) with smaller adhesive pad area (0.25 µm2) distributed over 4 smaller nanoislands was also examined. Immunostaining revealed that integrin localization was restricted to the nanoislands within the adhesive pads and the center square only, and areas between the adhesive regions were mostly devoid of integrin staining (Fig. 2A). In some instances, integrin staining was present over non-adhesive areas spanning adhesive nanoislands corresponding to ‘cell bridging’ (Lehnert et al., 2004; Zimmermann et al., 2004; Rossier et al., 2010). We do not expect that integrins over the non-adhesive areas contribute significantly to adhesive force since there is no FN underneath them (Fig. 1D) to support anchorage to the substrate. Notably, the distribution and intensity of integrin staining on nanoislands differed significantly among the different geometrical patterns, with higher signal intensity to the peripheral adhesive pads for the larger nanoislands (500 and 1000 nm) and higher integrin localization to the center square for the smaller nanoislands (250 and 333 nm).

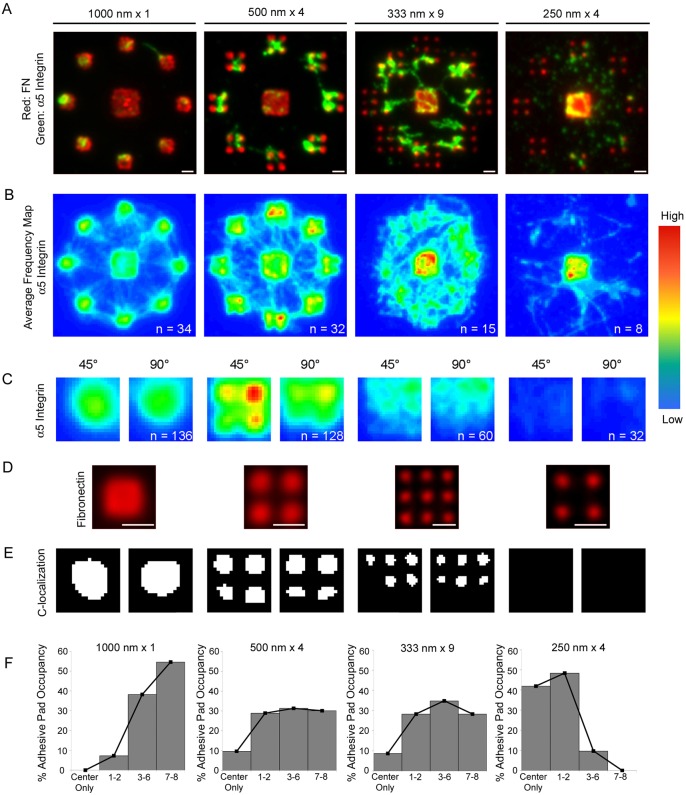

Fig. 2.

Nanoscale adhesive geometry modulates integrin–FN clustering. (A) Integrin recruitment to Alexa-Fluor-555-labeled FN nanopatterns was analyzed using a cross-linking/extraction method that selectively retains FN-bound integrins. Fluorescence microscopy images for integrin binding (green) to FN (red) adhesive clusters with different geometrical configurations. Scale bars: 1 µm. (B) Frequency maps for integrin recruitment to adhesive zones generated by stacking individual images. The pseudo-color range represents the frequency of integrin localization to a spatial location with ‘warmer’ colors reflecting a higher frequency of localized integrin staining. (C) High magnification frequency maps for integrin recruitment to adhesive pads for the 45° and 90° orientations. (D) FN nanoislands in adhesive pads. Scale bars: 1 μm. (E) Binary images of the area corresponding to colocalization of integrin recruitment and FN nanoislands for the 45° and 90° pad orientation; images are oriented such that the edge closer to the center pad is at the top. (F) Frequency histograms of pad occupancy. Statistical analyses of frequency distributions revealed the following differences (P<0.05): 1000 nm×1>500 nm×4 = 333 nm×9>250 nm×4.

In order to perform quantitative analyses of integrin recruitment and clustering to FN nanopatterns, individual images were stacked and color coded to generate frequency maps of integrin–FN clustering (Fig. 2B,C). This analysis exploits the controlled spatial arrangement of the FN islands and allows us to extract the dominant spatial localization of integrins across multiple cells. As such, these frequency map images represent a better descriptor of integrin localization for the cell population compared to images of individual cells. This type of analysis has been used to identify spatial patterns of proliferation and cell density in multicellular assemblies and filters out low frequency occurrences, such as noise (Nelson et al., 2005; Nelson et al., 2006). Fig. 2B presents frequency maps for cells adhering to the four adhesive zone configurations, and higher magnification images for the adhesive pads in the 45° and 90° orientations are shown in Fig. 2C. In addition, the frequency maps were overlaid onto images of the FN nanoislands (Fig. 2D) to identify colocalization of integrin and FN within the adhesive pads (Fig. 2E). On 1000 nm×1 patterns, integrins were recruited to the adhesive pads and center square, and integrins uniformly localized to the available single FN nanoisland in the adhesive pads. On 500 nm×4 patterns, integrins were recruited to the center square as well as the nanoislands in the adhesive pads. Although integrins localized to the 4 nanoislands in the adhesive pad, there was higher frequency of localization to the nanoislands that were closer to the center square. This enrichment in integrin recruitment is most evident on the adhesive pad with the 45° orientation. For 333 nm×9 patterns, integrin recruitment was enriched to the center square compared to the adhesive pads, where the frequency maps revealed more diffuse integrin localization. In addition, integrins recruited to adhesive pads colocalized with the FN nanoislands, but only to those that were closer to the center square. On the 250 nm×4 patterns, integrins clustered exclusively on the center square and very little integrin staining was evident on the nanoislands. These results demonstrate that stable integrin–FN clusters exhibit a nanoscale area threshold (333 nm islands corresponding to 0.11 µm2) below which no stable complexes are formed.

It was clear from examining multiple images that the number of adhesive pads occupied by integrins for a given adhesive zone (each zone presents 8 adhesive pads to one cell) was dependent on the adhesive pad geometric configuration. We therefore scored the number of adhesive pads (out of 8) staining positive for integrin–FN clustering and generated histograms for adhesive pad occupancy by integrins (Fig. 2F). For 1000 nm×1 patterns, integrin–FN clusters predominantly occupied three or more adhesive pads with over 50% of cells showing occupancy on all 8 adhesive pads. In contrast, for 250 nm×4 patterns integrins showed low pad occupancy with over 90% of adhesive zones having two or less adhesive pads occupied by integrins. The 500 nm×4 and 333 nm×9 patterns resulted in integrin pad occupancies that were equally distributed from partial to full occupancy. These findings also support our conclusion that stable integrin–FN clusters exhibit a nanoscale area threshold (0.11 µm2), below which no stable complexes are formed.

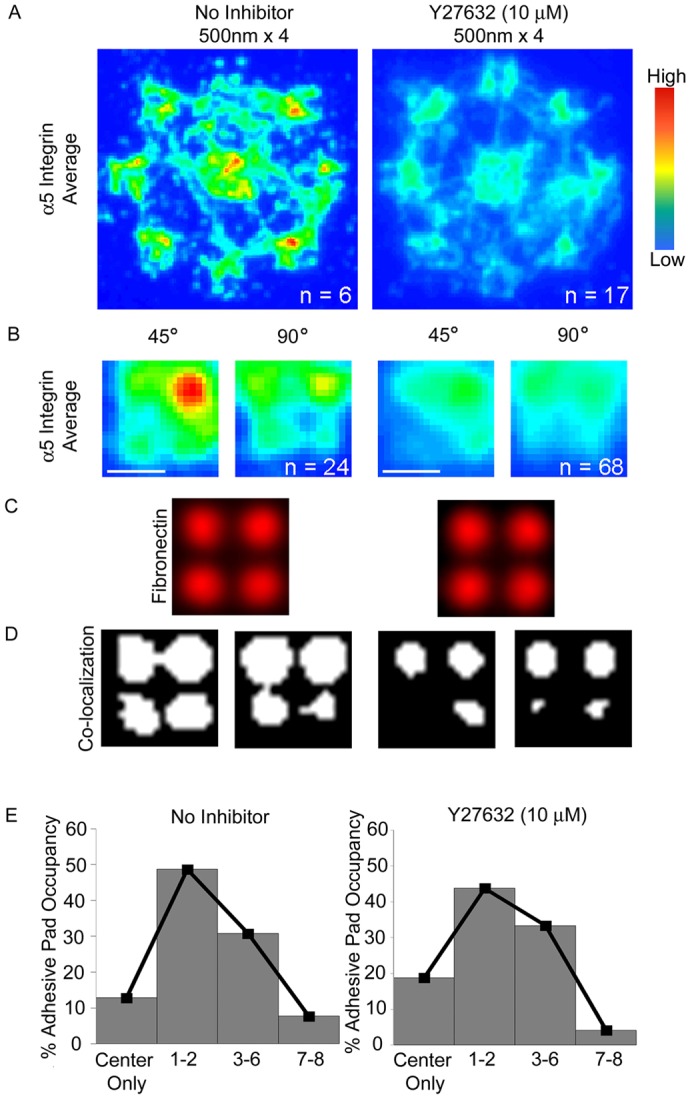

To further characterize these integrin–FN clusters, we examined the contributions of Rho-kinase activity to steady-state integrin–FN cluster formation on nanopatterned substrates. Contractility inhibitors have divergent effects on nascent adhesions compared to mature FAs. Inhibitors of Rho-kinase and actomyosin contractility dissolve mature FAs and reduce corresponding adhesive forces (Burridge and Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, 1996; Amano et al., 1997; Balaban et al., 2001; Tan et al., 2003; Dumbauld et al., 2010). In contrast, inhibition of Rho-kinase upregulates the number of nascent adhesions in the lamellipodium (Alexandrova et al., 2008) whereas the formation rate of nascent adhesions is myosin-II-independent (Choi et al., 2008). We examined whether inhibition of contractility using Y-27632, a specific inhibitor of Rho-kinase that reduces myosin light chain phosphorylation, cell contractility, FA assembly and FA-dependent forces (Dumbauld et al., 2010; Kuo et al., 2011), influences assembly of integrin–FN clusters on nanoislands. Cells were cultured on FN nanopatterns overnight and treated with Y-27632 (10 µM) 30 min prior to analysis. For 500 nm×4 patterns, treatment with Y-27632 reduced the frequency of integrin localization within the nanoislands (Fig. 3A,B). However, treatment with Y-27632 did not eliminate integrin localization to FN nanoislands (Fig. 3D) or alter pad occupancy (Fig. 3E), especially when compared to the unoccupied adhesive pads for the 250 nm×4 islands (Fig. 2E). These results demonstrate that Rho kinase activity reduces, but does not eliminate, steady-state integrin–FN clustering, and does not affect pad occupancy. The partial myosin dependence suggests that these engineered nanoscale, steady state adhesions reflect the properties of initial adhesions that are constrained from subsequent increase in area by the geometric arrangement of the ECM.

Fig. 3.

Effects of Rho-kinase inhibition on integrin–FN clustering on nanoscale patterns. (A) Frequency maps for integrin clustering to 500 nm×4 patterns for control and Y-27632 (10 µM)-treated cells. (B) High magnification frequency maps for integrin recruitment to adhesive pads for the 45° and 90° orientations. Scale bars: 1 µm. (C) FN nanoislands in adhesive pads. (D) Binary images of area corresponding to colocalization of integrin recruitment and FN nanoislands for the 45° and 90° pad orientation; images are oriented such that the edge closer to the center pad is at the top. (E) Histograms of pad occupancy.

Nanoscale adhesive geometry modulates adhesive force

To examine the effects of nanoscale adhesive geometry on adhesive forces, we quantified the force required to detach cells from the adhesive zones after a 16-hour culture time point using a spinning disk device (García et al., 1998b; Gallant et al., 2005). A detachment profile (adhesion fraction f versus shear stress τ) was fit to a sigmoid curve to obtain the shear stress for 50% detachment (τ50), defined here as the cell adhesion strength. Fig. 4A presents typical detachment profiles showing sigmoidal decreases in the fraction of adherent cells as a function of shear stress for two nanopattern configurations. The right-ward shift in the detachment profile for the 1000 nm×1 pattern compared to the center square-only pattern (no adhesive pads) reflects a 2.2-fold increase in adhesive force.

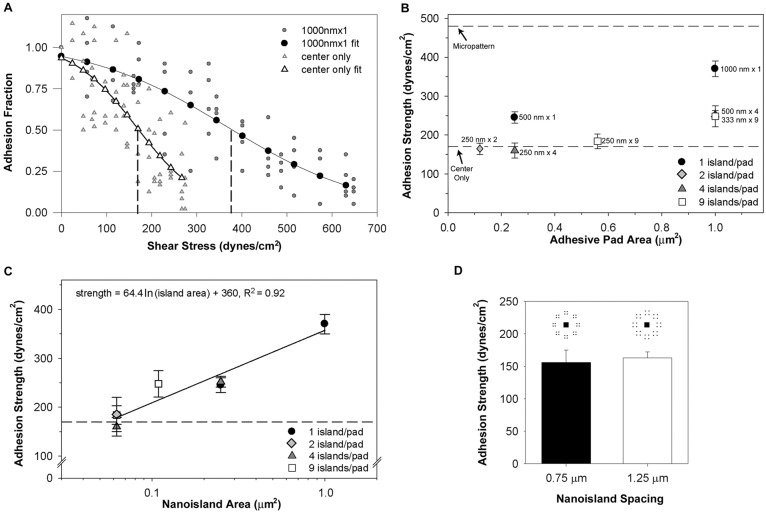

Fig. 4.

Nanoscale adhesive geometry regulates cell adhesion strength. Cell adhesive force to FN nanopatterns was measured using a spinning disk assay. (A) Detachment profiles (adhesive fraction versus shear stress) for cells adhering to 1000 nm×1 and center-only patterns. Experimental points were fitted to a sigmoid curve to calculate the shear stress for 50% detachment, which represents the mean adhesion strength. Vertical dashed lines show the shear stress for 50% detachment for each profile. (B) Adhesion strength as a function of adhesive pad area for different nanoisland configurations. Values are means ± s.e.m. The top and bottom dashed lines correspond to the adhesion strengths for a 10 µm diameter circular area and the center-only pattern, respectively. (C) Adhesion strength as a function of individual nanoisland area (log scale). Values are means ± s.e.m., and logarithmic (natural base) fit is shown (solid line). The dashed line corresponds to the adhesion strength for the center-only pattern. Results for 0.0625 µm2 and 0.250 µm2 comprise 3 (250 nm×2, 250 nm×4, 250 nm×9) and 2 (500 nm×1, 500 nm×4) nanoisland patterns, respectively. (D) Adhesion strength values for 250 nm×4 patterns with different inter-island spacings (0.75 versus 1.25 µm), showing no differences in adhesive force.

Cell adhesion strength was quantified for adhesive zone configurations with different adhesive pad areas, nanoislands sizes, and number of nanoislands. Fig. 4B summarizes results for adhesive force as a function of adhesive pad area and number of nanoislands per adhesive pad. The upper bound (top dashed line) represents the adhesion strength for a 10 µm diameter micropatterned area (adhesive area 78.5 µm2), whereas the lower bound (bottom dashed line) corresponds to the adhesion strength for a pattern with 2×2 µm center square but no adhesive pads or nanoislands (adhesive area 4.0 µm2). For most nanopattern configurations, adhesion strength values were higher than the lower bound, indicating that FN nanoislands significantly contribute to adhesive force. A 650% reduction in total available adhesive area (10 µm diameter circle versus 1000 nm×1 pattern) resulted in only a 25% reduction in adhesive force. This result is consistent with our previous work demonstrating that adhesive strength is controlled by small adhesive areas at the periphery of the cell (corresponding to FAs) and that the majority of the available adhesive interface does not contribute significantly to adhesive force (Gallant et al., 2005).

The adhesion strength value for all patterns with nanoisland dimensions below 333 nm was equivalent to the lower bound (no adhesive pads), indicating no appreciable contributions to adhesive force for these nanoislands (Fig. 4B). For example, there are no differences in adhesion strength for 250 nm islands regardless of whether each pad contained 2, 4 or 9 islands, and the adhesion strength for these nanoislands is equivalent to center-only patterns that have no nanoislands. This result is consistent with the integrin recruitment results and shows the functional consequences of the area threshold of integrin–FN clustering to adhesive force. Furthermore, we noticed that the 500 nm×1 and 500 nm×4 patterns, which have same nanoisland dimensions but different number of nanoislands (1 versus 4), and therefore, different adhesive pad areas (0.25 versus 1.0 µm2), produced equivalent adhesion strength values (245±15 versus 252±11 dynes/cm2). This result suggests that individual nanoisland area, independently from the number of nanoislands and pad adhesive area, controls adhesion strength. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 4C, when adhesion strength is plotted as a function of the individual nanoisland area, the data points from different nanopattern configurations collapse into a single curve. Non-linear regression with a logarithmic curve indicated that this functional dependence accounts for over 92% of the variance in the data (P<0.0007). Additionally, no differences in adhesion strength were observed between configurations with the same adhesive pad area (0.25 µm2) and number of islands (4) but with different inter-island spacings (0.75 versus 1.25 µm; Fig. 4D), indicating that the spacing between nanoislands does not contribute appreciably to adhesive force. This analysis demonstrates that, above an area threshold of 0.11 µm2, individual nanoisland area, and not the geometric arrangement of the adhesive area (number of islands, island spacings, total pad area), regulates the adhesive force generated by stable integrin–FN clusters. Below this area threshold, no appreciable adhesive forces are generated, correlating with the lack of stable integrin–FN clusters at steady state.

Talin controls the stable assembly of integrin–FN clusters at nanoscale dimensions

What determines the area threshold for assembly of stable integrin–FN clusters? Extrinsic, cell-independent factors related to ligand presentation/density could dictate integrin clustering. However, the observed area threshold corresponds to a nanoisland area that is considerably (at least 50-fold) larger than the minimal ligand spacing (∼100 nm) required for focal adhesion assembly and spreading (Massia and Hubbell, 1991; Arnold et al., 2004; Cavalcanti-Adam et al., 2007). Alternatively, cell-dependent, intrinsic mechanisms could regulate this ECM area ‘switch’ in the assembly of integrin–FN clusters. We first postulated that the nanoscale area threshold in integrin–FN clustering results from an insufficient number of activated and bound integrins required to establish a stable nascent integrin cluster. Therefore, we hypothesized that increased integrin activation would overcome this ‘nanolimit’ for stable integrin recruitment.

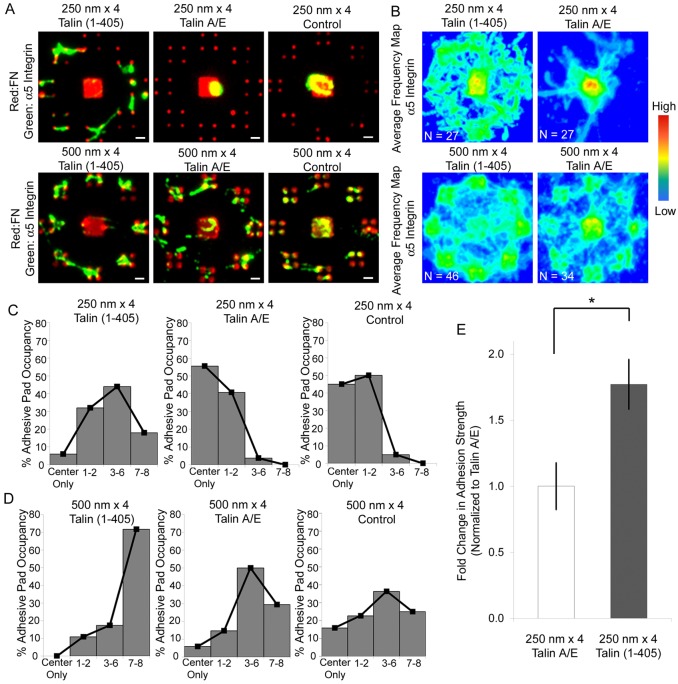

Talin is an elongated (∼60 nm) flexible anti-parallel dimer that interacts with several proteins in FAs (Critchley, 2009). Notably, the FERM domain in the globular N-terminus of talin [talin1(1–405)] binds to an NP(I/L)Y motif in the cytoplasmic tail of integrin-β subunits to activate the integrin (Calderwood et al., 1999; Tadokoro et al., 2003; Bouaouina et al., 2008; Goult et al., 2010). To determine whether integrin activation can overcome the ‘nanolimit’ of integrin–FN clustering on 250 nm islands, cells were transfected with plasmids encoding GFP–talin1(1–405) or GFP–talin1(1–405)A/E with an integrin binding-defective mutation (Bouaouina et al., 2008). Expression of talin1(1–405) significantly enhanced integrin clustering to the 250 nm islands compared to untransfected control cells, whereas the integrin binding-defective talin mutant had no effects on integrin recruitment (Fig. 5A,B). There were no significant differences in integrin recruitment on the larger 500 nm islands between talin head domain and controls (Fig. 5A,B). Expression of talin head domain also significantly altered the frequency of pad occupancy for the 250 nm×4 patterns. Talin1(1–405)-expressing cells on 250 nm×4 patterns mostly occupied three to six adhesive pads (Fig. 5C). Cells expressing the A/E mutant or control cells showed low pad occupancy on 250 nm×4 islands with over 95% of cells having two or less adhesive pads occupied by integrin clusters. The 500 nm×4 patterns exhibited integrin pad occupancies that were equally distributed from partial to full occupancy, but talin1(1–405) expression increased the full pad occupancy by 45% compared to A/E mutant and control cells (Fig. 5D). Importantly, adhesion strength values for talin1(1–405)-expressing cells on 250 nm×4 patterns were 1.8-fold higher than control talin1(1–405)A/E-expressing cells (Fig. 5E; P<0.05). These results demonstrate that talin-head domain triggers assembly of integrin–FN nanoclusters below the ECM area threshold and significantly increases adhesive force.

Fig. 5.

Talin head expression drives integrin–FN clustering at the nanoscale. Integrin binding analysis for talin-expressing cells. (A) Fluorescence microscopy images for integrin binding (green) to FN (red) adhesive zones. Scale bars: 1 µm. (B) Frequency maps for integrin recruitment on 250 nm×4 and 500 nm×4 patterns generated by stacking individual images. For 250 nm patterns, expression of talin1(1–405) induced recruitment and clustering of integrins compared to control cells. (C,D) Frequency histograms for pad occupancy on (C) 250 nm×4 and (D) 500 nm×4 patterns. (E) Cell adhesive force response to FN nanopatterns with talin head expression. Bar graphs represent fold change in adhesion strength over talin1(1-405)A/E-transfected cells adhering to 250 nm×4 patterns (means ± s.d.; *P<0.05).

Vinculin regulates nanoscale assembly of integrin–FN clusters by balancing adhesive force and cytoskeletal tension

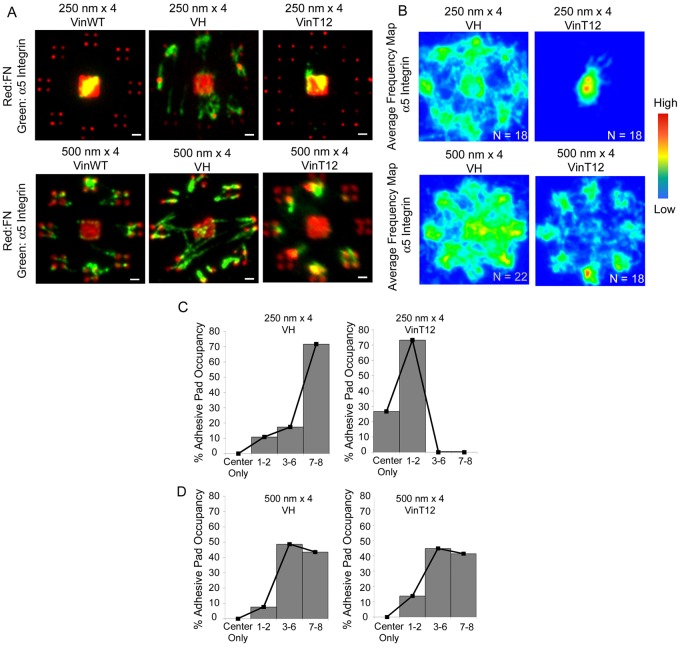

We next examined the role of the FA protein vinculin in the nanoscale organization of integrin–FN clusters. Vinculin contains a talin binding site in its globular head and actin binding sites in the tail domain, and interactions with these partners are regulated by an auto-inhibited conformation arising from strong head–tail binding (Cohen et al., 2006). Importantly, vinculin is a force-carrying component between adhesive sites and the cytoskeleton (Grashoff et al., 2010). The vinculin head domain promotes integrin clustering and increases residence times in mature FAs in spread cells (Cohen et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 2006; Humphries et al., 2007). We examined the effects of the vinculin head domain (VH, 1–851) on the area threshold of integrin–FN clustering using vinculin-null cells expressing VH. In contrast to cells expressing wild-type vinculin, cells expressing VH assembled integrin–FN clusters on the 250 nm nanoislands (Fig. 6A,B). These results show that the vinculin head domain can overcome the nanoscale limit of integrin–FN clustering, presumably via interactions with talin. The finding that cells expressing wild-type vinculin did not assemble stable integrin–FN clusters on the 250 nm nanoislands could be explained by the auto-inhibitory interaction between vinculin head and tail domains. To examine this possibility, we cultured vinculin-null cells expressing the vinculin T12 mutant (VinT12) on the nanopatterned substrates. VinT12 has a mutated head-tail interface that reduces the head-tail affinity 100-fold and thus exposes binding sites for talin and actin (Cohen et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 2006). This mutant also drives integrin clustering and FA assembly (Cohen et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 2006; Humphries et al., 2007). Surprisingly, expression of VinT12 failed to promote assembly of integrin–FN clusters on the 250 nm nanoislands even though robust clusters were assembled on the 500 nm patterns (Fig. 6A,B). Expression of VH also increased pad occupancy (Fig. 6C) on 250 nm islands, whereas VinT12 expression did not enhance pad occupancy. Pad occupancy was similar for VH- and VinT12-expressing cells on 500 nm islands (Fig. 6D). This result supports an alternative explanation in which the nanoscale area threshold for integrin-FN clustering is regulated by cytoskeletal tension.

Fig. 6.

Vinculin domains regulate stable assembly of integrin–FN nanoclusters. (A) Fluorescence microscopy images for integrin binding (green) to FN (red) adhesive zones for wild-type (WT), VH and VinT12-expressing cells on 250 nm×4 (top) and 500 nm×4 patterns (bottom). Scale bars: 1 µm. (B) Frequency maps for integrin recruitment on 250 nm×4 and 500 nm×4 patterns generated by stacking individual images. For 250 nm islands, expression of VH induced clustering of integrins to FN nanoislands, whereas VinT12 did not induce any recruitment. (C,D) Frequency histograms for pad occupancy for VH and VinT12 cells on (C) 250 nm×4 and (D) 500 nm×4 patterns.

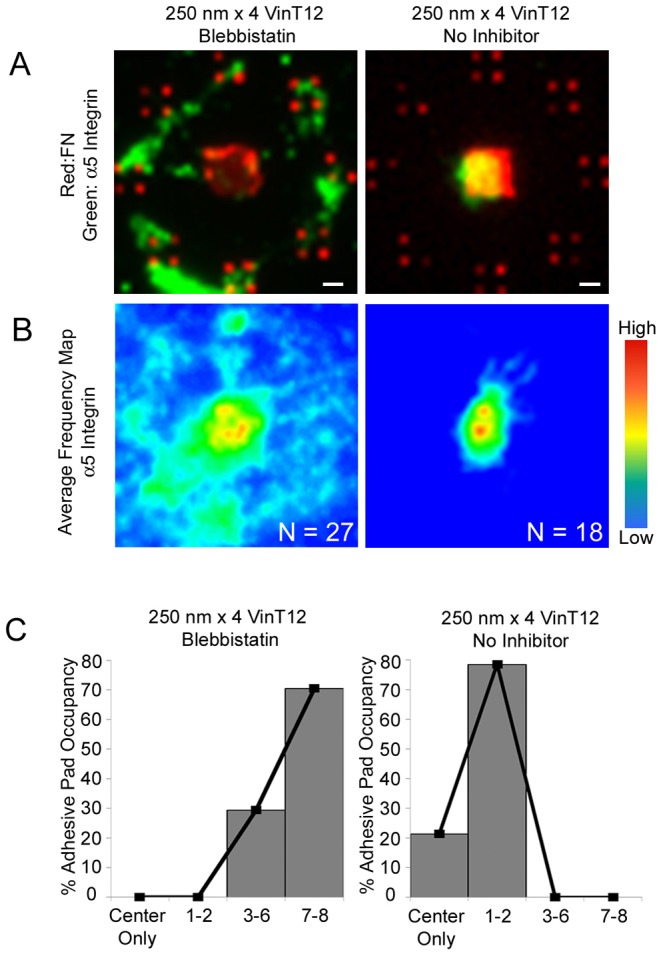

Whereas the head domain of VinT12 interacts with talin in a similar fashion as VH to drive integrin clustering, the tail domain of VinT12 can also interact with actin filaments to transmit cytoskeletal forces to adhesive structures. We therefore hypothesized that the area threshold for assembly of stable integrin–FN clusters at nanoscale adhesions is also regulated by cytoskeletal tension. Below the area threshold, the adhesive force generated by the integrin–FN clusters cannot support the cytoskeletal tensile force and the integrin clusters are disassembled or detached from the adhesive interface because of limited adhesive size of the nanoislands. To test this hypothesis, vinculin-null cells expressing VinT12 cultured overnight on the 250 nm nanoislands were treated with blebbistatin (20 µM) 60 min prior to analysis. Blebbistatin is an inhibitor of non-muscle myosin IIA that blocks actin–myosin contractility (Allingham et al., 2005). Cells expressing VinT12 and treated with blebbistatin displayed integrin–FN clusters on 250 nm islands similar to those in VH-expressing cells (Fig. 7A), whereas untreated VinT12-expressing cells did not exhibit integrin–FN clusters on 250 nm islands. Blebbistatin treatment had no effect on integrin–FN cluster formation on 250 nm nanoislands for cells expressing wild-type vinculin (supplementary material Fig. S3); this result is not surprising given the inability of cells expressing wild-type vinculin to form integrin–FN clusters on the 250 nm islands. Blebbistatin treatment also increased adhesive pad occupancy compared to control VinT12-expressing cells (Fig. 7B). These results demonstrate that a reduction in the cytoskeletal tension applied to integrin–FN nanoclusters in the presence of a vinculin mutant that drives integrin clustering allows for stable assembly of adhesive structures below the ECM area nanolimit. Taken together, these findings support a model where stable FA assembly and ECM–cell adhesive forces are regulated by the force equilibrium between cytoskeletal tension and adhesive forces.

Fig. 7.

Actomyosin contractility controls stabilization of integrin–FN clusters at nanoscale dimensions. (A) Fluorescence microscopy images for integrin binding (green) to FN (red) adhesive zones of VinT12 cells on 250 nm×4 patterns in the presence or absence of blebbistatin (20 µM). Scale bars: 1 µm. (B) Frequency maps for integrin recruitment on 250 nm×4 for VinT12 cells in the presence or absence of blebbistatin (20 µM), generated by stacking individual images. (C) Frequency histograms for pad occupancy of VinT12 cells on 250 nm×4 patterns in the presence or absence of blebbistatin (20 µM).

Discussion

A standing question in mechanobiology is how cells sense geometrical ECM cues and transmit local forces at FAs (Bershadsky et al., 2006; Vogel and Sheetz, 2006; Gardel et al., 2010; Parsons et al., 2010). Several studies have shown that ECM ligand spacing regulates FA and stress fiber assembly, cell spreading and migration, and adhesive forces (Massia and Hubbell, 1991; García et al., 1998a; Maheshwari et al., 2000; Coussen et al., 2002; Koo et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2003; Arnold et al., 2004; Cavalcanti-Adam et al., 2007; Petrie et al., 2010; Selhuber-Unkel et al., 2010). However, whether the geometric organization of the ECM ligand regulates FA assembly and force transmission has not been addressed. Here, we used nanopatterned substrates with defined geometrical arrangements of FN to restrict the formation of adhesive structures to the nanoscale dimensions characteristic of FAs to study how nanogeometry regulates assembly of integrin–FN clusters and the generation of ECM–cell anchorage forces. The smallest nascent adhesion size reported is 0.19 µm2 (Choi et al., 2008), although these authors speculated that the actual size is smaller. Our nanopatterning approach offers the ability to identify even smaller adhesive structures and we showed formation of tiny 0.06 µm2 adhesions (Figs 6, 7). We demonstrated that integrin clustering on FN islands and adhesive force were modulated by nanoscale ECM area; below a threshold of 0.11 µm2, no stable integrin–FN clusters were assembled or adhesive forces generated. Expression of talin head or vinculin head domains that increase integrin activation or clustering overcame this nano-limit. Inhibition of myosin contractility in cells expressing a vinculin molecule that enhances the coupling between the force-generating actin cytoskeleton and integrins also restored integrin–FN clustering below the area threshold. We conclude that the size of the integrin–FN clusters required for stable FA assembly and force generation has an ECM area threshold that is not constant, but is instead regulated by intracellular proteins (talin, vinculin) that influence the force equilibrium between the adhesive force generated by the integrin–FN clusters, which is related to the nanoscale area and number of FN-bound integrins, and the cytoskeletal tension applied to the clusters.

A critical advantage of our patterning strategy is that the overall cell shape is constrained within the 10 µm diameter adhesive zone for all nanopattern configurations. This approach allows decoupling of integrin–FN cluster formation from cell spreading and cells cannot spread (or retract). Importantly, the distance between the adhesive pads containing the nanoislands and the center square is fixed across all nanopattern configurations, ensuring equivalent force loading in all experiments. Although we observed a higher frequency of integrin–FN clusters on nanoislands that were closer to the center square, we do not expect that this reduced distance alters force loading because this distance is significantly smaller than the overall distance between the adhesive pad and the center square. Indeed, our calculations estimate that enrichment of integrin–FN clusters towards the center square altered the resultant adhesive force by less than 1.3%. Finally, while the focus of the present study was to analyze the assembly of stable, steady-state integrin–FN clusters and adhesion strength, in the future, it will be of interest to perform time course analyses of integrin–FN complex assembly and adhesive forces. Unfortunately, this experiment is not presently possible due to technical limitations associated with live cell imaging of nanometer-scale adhesive clusters on the gold-coated substrates.

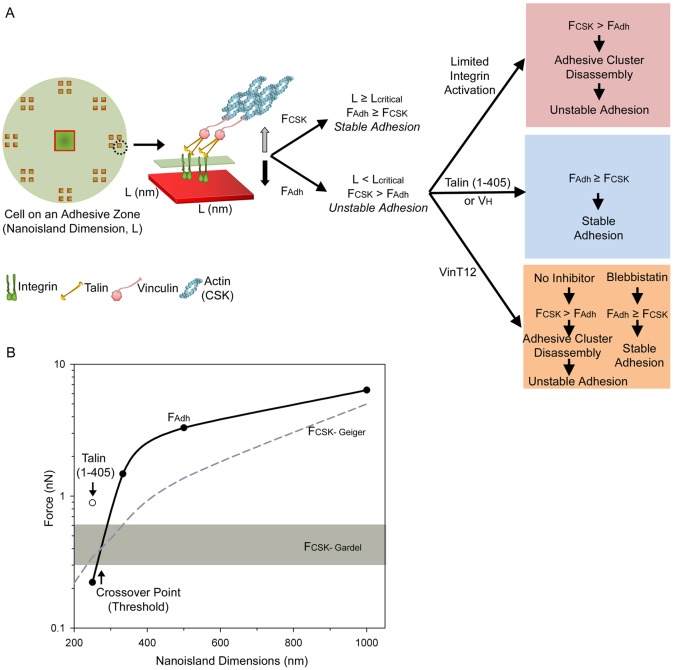

We propose a force equilibrium model for the ECM-area-regulated assembly of stable integrin–FN clusters (Fig. 8). Activated integrins bind to ECM ligands in the adhesive interface and assemble into small adhesive clusters containing talin and vinculin. The actin cytoskeleton applies tensile force to these nascent adhesive clusters via actin-myosin contractility. This cytoskeletal force is balanced by the adhesive force generated by the integrin–FN clusters. Below an area threshold (0.11 µm2), the adhesive force cannot support the cytoskeletal tension and the integrin cluster is unstable and is disassembled or detached from FN. Above this area threshold, the integrin–FN cluster is large enough to generate sufficient force to support the applied tension (Fig. 8A). The ECM area threshold for assembly of stable integrin–FN clusters is therefore regulated by (i) the adhesive force generated by the integrin–FN clusters, which is related to the nanoscale ECM area and number of bound integrins, and (ii) the cytoskeletal tension applied to the clusters. Increases in the adhesive force generated by the integrin–FN clusters via integrin activation or clustering through binding to talin head or vinculin head result in a stable adhesive cluster that can support cytoskeletal tension with smaller adhesive areas (Fig. 8A). Conversely, decreases in the applied cytoskeletal tension via inhibition of myosin contractility result in a reduction in the force driving disassembly of the integrin clusters (Fig. 8A). Fig. 8B provides quantitative relationships that fully support this model. Because the size and position of the adhesive clusters and cell morphology are defined in our experimental system, we can convert the measured values for adhesion strength (Fig. 4) to the cell–ECM adhesive force generated on the nanoislands (FAdh) as a function of nanoisland dimension (solid black line). For the cytoskeletal tension (FCSK), we considered two estimates based on traction forces measured on deformable substrates. Gardel and colleagues recently reported the traction stresses during the initial stages of FA assembly (Stricker et al., 2011); the range for maximum traction forces for these nascent complexes is indicated by the gray box in Fig. 8B. Plotted also is the traction force for larger, mature FAs derived by Geiger and colleagues (Balaban et al., 2001) that increases with FA size (dashed gray line) (Balaban et al., 2001). Several noteworthy observations are evident from Fig. 8B. First, FCSK is larger than FAdh for small nanoislands but there is a cross-over point for which FAdh becomes larger than FCSK. This cross-over point corresponds to the area threshold. For either FCSK model, the area threshold occurs below areas with dimensions below 333 nm (∼280–300 nm) in excellent agreement with our experimental data for integrin–FN cluster assembly (Fig. 2). Remarkably, when the value for adhesion strength for the talin head domain on 250 nm nanoislands is included (open symbol), the resulting FAdh exceeds the FCSK, also in agreement with the result that expression of talin head promotes assembly of stable integrin–FN clusters on the 250 nm nanoislands (Fig. 5). This finding shows that talin-based integrin activation stabilizes integrin–FN clusters and enables these nanoscale structures to transmit large adhesive forces.

Fig. 8.

Force equilibrium model for ECM-area-regulated assembly of integrin–FN clusters. (A) On nanoislands (side dimension L), activated integrins bind to FN and assemble into small adhesive clusters containing talin and vinculin. The stability of these nascent adhesive clusters is dependent on the balance between the force of integrin–FN adhesion (FAdh) and the cytoskeleton-mediated tensile force (FCSK). For nanoislands with dimensions larger than the threshold area (L≧Lcritical), the integrin–FN adhesive force can support the applied cytoskeletal tension and stable integrin–FN clusters assemble on nanoislands. For nanoislands with dimensions smaller than the threshold area (L≤Lcritical), the applied cytoskeletal tension exceeds the integrin–FN adhesive force and no stable integrin–FN complexes are assembled. Recruitment of talin/vinculin and modulation of the applied cytoskeletal tension to the integrin–FN clusters alters the force equilibrium to regulate integrin–FN complex assembly. (B) Plot for FAdh and FCSK as a function of nanoscale area showing area threshold (cross-over point). FAdh (solid black line) was derived from experimental adhesion strength values (filled circles); open circle shows the FAdh for talin1(1–405)-expressing cells. Estimates for FCSK based on the work of Gardel and colleagues (Stricker et al., 2011) are shown as a gray box and those based on the work of Geiger and colleagues (Balaban et al., 2001) are shown as a dashed line (see text).

This force equilibrium model for ECM-area-controlled assembly of integrin–FN clusters provides a simple, local regulatory mechanism for the assembly/disassembly of adhesive structures. During leading edge protrusion in cell migration, small (∼0.19 µm2) nascent adhesions (Choi et al., 2008) assemble and either disassemble or become stable and grow into mature adhesions (Parsons et al., 2010). The mechanism(s) regulating these adhesion dynamics is not clear but two models have been proposed (Parsons et al., 2010). In the first model, nucleation of adhesion clusters is initiated by integrin binding, clustering and recruitment of cytoskeletal proteins (e.g. vinculin, talin), and these nascent structures grow and mature in response to contractile forces. In the second model, FA assembly is coupled to actin polymerization wherein vinculin and FAK bind to Arp2/3 and these complexes then bind ECM-bound integrins to stabilize the nascent adhesion in a myosin-independent fashion. The force equilibrium model is consistent with elements of first model and provides a simple biophysical nanoscale switch to control the nucleation and growth of adhesive structures. The finding that integrin activation via binding of talin head or driving clustering via vinculin head domain overcomes the nanoscale limit for stable integrin–FN cluster assembly supports the explanation that integrin activation and binding drive assembly of nascent adhesive clusters (Cohen et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 2006; Humphries et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2008). The assembly of integrin clusters on 250 nm nanoislands in the presence of blebbistatin is also consistent with previous reports showing that myosin activity is not required for formation of nascent adhesions (Alexandrova et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2008). Our results with the vinculin head domain driving assembly of integrin–FN nanoclusters suggest that Arp2/3 is not directly involved in this process because this vinculin domain lacks that the proline-rich strap (amino acids 851–880) that contains the Arp2/3 binding site (DeMali et al., 2002). Finally, the force-balance model also provides an attractive explanation for mechanosensitive changes in FA assembly. For instance, application of local external forces to adhesive clusters would perturb the local force balance and drive FA growth to increase the net adhesive force. This prediction is consistent with the observation that application of external forces to adhesive plaques results in Rho-dependent directional focal adhesion growth (Riveline et al., 2001). Similarly, changes in substrate stiffness could alter the local force balance to regulate the size of FA structures without significant changes in local cytoskeletal forces, in good agreement with published results (Yeung et al., 2005; Aratyn-Schaus et al., 2011).

In conclusion, we demonstrate that integrin–FN clustering and adhesive force are strongly modulated by the geometry of the nanoscale adhesive area. Stable assembly of integrin–FN clusters and adhesive force depend on the area of individual adhesive nanoislands and not the number of adhesive contacts or total adhesive area. Importantly, the minimal size of integrin–FN clusters required for FA assembly and force transmission exhibits an area threshold that is not constant, but is instead regulated by recruitment of talin and vinculin and the cytoskeleton tension applied to these adhesive clusters. We propose that this dynamic area threshold results from an equilibrium between pathways controlling adhesive force, cytoskeletal tension, and the structural linkage that connects these forces. This force equilibrium acts as a simple, local regulatory mechanism for the assembly/disassembly of nascent adhesive structures and the transmission of adhesive forces.

Materials and Methods

Cells and reagents

NIH3T3 fibroblasts (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cell culture reagents, including human plasma FN and Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), were purchased from Invitrogen. BSA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies against α5 integrin (ab1921, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and human FN (anti-hFN polyclonal antibody, Sigma-Aldrich) were used for immunostaining. Alexa-Fluor-488-conjugated secondary antibodies and Alexa Fluor 555 succinimidyl ester were purchased from Invitrogen. Cross-linker 3,3-dithiobis(sulfosuccinimidylpropionate) (DTSSP) was purchased from Pierce Chemical (Rockford, IL, USA). Poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) elastomer and curing agent (Sylgard 184) were produced by Dow Corning (Midland, MI, USA). ZEP520A was purchased from Zeon Chemicals (Tokyo, Japan). Amyl acetate was produced by Mallinckrodt Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA), and n-methyl pyrrolidinone (NMP, 1165 Remover) was obtained from MicroChem (Newton, MA, USA). Tri(ethylene glycol)-terminated alkanethiol [HS-(CH2)11-(OCH2CH2)3-OH; EG3] and carboxylic acid-terminated alkanethiol [HS-(CH2)11-(OCH2CH2)6-OCH2-COOH; EG6-COOH] were purchased from ProChimia Surfaces (Sopot, Poland). N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), and 2-(N-morpho)-ethanesulfonic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Talin plasmids and expression in cells

NIH3T3 fibroblasts were transfected using an Amaxa Nucleofector II (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). Constructs for GFP–talin1(1–405) and GFP–talin1(1–405)A/E with integrin binding-defective mutation have been described (Bouaouina et al., 2008). Talin1(1–405) included the entire FERM and has been previously shown to activate α5β1 integrin (Bouaouina et al., 2008). For each sample, 2 million cells were resuspended in 100 µl of Nucleofector II Solution R (Lonza) with 2.5 µg of plasmid and transfected using program U-30. Immediately after transfection, cells were transferred to 1.5 ml centrifuge tube containing 500 µl of pre-warmed RPMI 1640 and incubated for 15 min. Cells were then transferred into 100 mm plates containing normal growth medium. 24 h after transfection, cells were enriched using flow cytometry for GFP expression and studies were performed 48 hours after transfection.

Vinculin cell lines

Retroviral plasmids pTJ66-tTA and pXF40 were previously described (Gersbach et al., 2006). eGFP-C1 WT vinculin and eGFP-T12 vinculin plasmids have been described (Chen et al., 2005). One AgeI restriction site was inserted into the multiple cloning site of pXF40, the retroviral expression vector. The oligonucleotides 5′-AGCTTGTCAGCTACCGGTGCTACTGCA-3′ and 5′-AGCTTGCAGTAGCACCGGTAGCTGACA-3′ (AgeI sequences underlined) were annealed together, creating HindIII-compatible overhangs at each end. This product was then ligated into a linearized pXF40 vector which had been digested with HindIII. Finally, the eGFP–vinculin constructs were digested from the pEGFP-C1 with AgeI and SalI and ligated into the SalI and AgeI-digested pXF40 vector. The pXF40-eGFP-vinculin WT, VH and T12 vectors transcribe the eGFP-vinculin gene from the tetracycline-inducible promoter. All vectors were verified by sequencing the ligation points.

Retroviral stocks were produced by transient transfection of helper virus-free øNX amphotropic producer cells with plasmid DNA as previously described (Byers et al., 2002). Vinculin-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Xu et al., 1998), a kind gift from Eileen Adamson (Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute), were plated on tissue culture polystyrene at 2×104 cells/cm2 24 h prior to retroviral transduction. Cells were transduced with 0.2 ml/cm2 of equal parts pTJ66-tTA and pXF40-eGFP-vinculin retroviral supernatant supplemented with 4 µg/ml hexadimethrine bromide and 10% fetal bovine serum, and centrifuged at 1200 g for 30 min in a Beckman GS-6R centrifuge with a swinging bucket rotor. Retroviral supernatant was replaced with growth medium (DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin G sodium, 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate). Five days after transduction, eGFP-expressing cells were FACS sorted, expanded, and either used for experimentation or cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen for later use. Expression of vinculin constructs was verified by western blot and immunofluorescence microscopy (data not shown).

Nanopatterned surfaces

Mixed self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of tri(ethylene glycol)-terminated (EG3) and carboxylic acid-terminated (EG6-COOH) alkanethiols on gold were used to present anchoring groups for covalent immobilization of FN within a non-fouling background as reported earlier and showed in supplementary material Fig. S1 (Coyer et al., 2007; Coyer et al., 2011).

Cell seeding and integrin cross-linking

Alexa-Fluor-555-conjugated FN to was used to visualize patterns of printed protein. In order to leave free primary amines on FN for tethering to mixed self-assembled monolayers, a ratio of 25∶1 w/w of FN to amine-reactive Alexa Fluor 555 succinimidyl ester was used in the reaction. Cells were seeded on FN-patterned substrates at 235 cells/mm2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum and cultured overnight (>16 h) for all experiments.

Bound integrins were visualized using a cross-linking and extraction method (García et al., 1999; Keselowsky and García, 2005). Cells patterned on substrates were incubated in cold DTSSP cross-linker (1.0 mM in PBS) for 30 min to cross-link integrins to their bound ligand. DTSSP was then quenched using 50 mM Tris-buffered saline, followed by extraction of uncross-linked components of the cell with 0.1% SDS supplemented with protease inhibitors (16.7 µg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml aprotinin). After extraction, samples were fixed in cold paraformaldehyde (3.7% in PBS) for 5 min, blocked in blocking buffer (5% goat serum in PBS) for 30 min, and incubated with primary antibody (anti-α5-integrin, 5 µg/ml) diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h at 37°C. Primary antibodies were visualized using Alexa-Fluor-488-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG, 10 µg/ml) diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h at 37°C. Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse E400 fluorescence microscope, Nikon CFI Apo TIRF 60× oil/1.49 NA objective and Image-Pro image acquisition software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA) at fixed exposures and illumination conditions. Frequency map images were produced by stacking and averaging individual images for a given condition using Image Pro software. In order to evaluate pad occupancy, individual images with positive integrin staining for the center area (indicating a cell) were scored for the number of adhesive pads within an adhesive cluster with positive integrin localization and normalized by the total number of patterns counted to generate a cumulative distribution.

For talin studies, 48 h after transfection, cells were seeded onto nanopatterns and cross-linking/extraction was performed 72 h after initial transfection. For vinculin studies, eGFP–vinT12-, eGFP–WT-, or eGFP–VH-expressing cells were seeded overnight on the nanopatterns followed by cross-linking extraction as described earlier. Inhibition experiments were performed on cells cultured overnight on nanopatterns and treated with Y-27632 (10 µM) and (−)-blebbistatin (20 µM) for 30 min and 60 min prior to analysis, respectively.

Adhesive force measurements

Cell adhesion strength was measured using a spinning disk system (García et al., 1998b; Gallant et al., 2005). Patterned coverslips with adherent cells cultured overnight were spun in PBS + 2 mM dextrose for 5 min at a constant speed in a custom-built device. The applied shear stress (τ) is given by the formula τ = 0.8r(ρμω3)1/2, where r is the radial position, ρ and μ are the fluid density and viscosity, respectively, and ω is the spinning speed. After spinning, cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100, stained with ethidium homodimer-1 (Invitrogen), and counted at specific radial positions using a 10× objective lens in a Nikon TE300 microscope equipped with a Ludl motorized stage, Spot-RT camera, and Image Pro analysis system. Sixty-one fields (80–100 cells/field before spinning) were analyzed and cell counts were normalized to the number of cell counts at the center of the disk, where the applied force is zero. The fraction of adherent cells (f) was then fit to a sigmoid curve f = 1/(1+exp[b(τ−τ50)]), where τ50 is the shear stress for 50% detachment and b is the inflection slope. τ50 represents the mean adhesion strength for a population of cells.

Calculation of adhesive forces for force equilibrium model

Adhesion strength data (Fig. 4) was converted to adhesive forces using a simple mechanical equilibrium model for a nearly spherical adherent cell (Gallant et al., 2005; Gallant and García, 2007). Traction forces based on those derived by Geiger were obtained by multiplying the nanopattern area by the stress constant (5.5 nN/µm2) reported by this group (Balaban et al., 2001). Estimates for traction forces based on Gardel were obtained from the range of forces corresponding to the FA growth phase in figure 3 in Stricker et al. (Stricker et al., 2011).

Statistics

Non-linear regression analysis was performed using SigmaPlot (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). Results were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test for pairwise comparisons unless otherwise stated. Statistical comparisons for pad occupancy were completed using Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric tests followed by pair-wise comparisons adjusted by multiplying the P-value by the number of comparisons. All statistical analysis was completed using SYSTAT 11.0 (Systat Software).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Brown, G. Spinner, and N. D. Gallant for their support with the fabrication of templates. We thank K. L. Templeman for preparation of plasmids.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01-GM065918 to A.J.G. and R01-GM41605 to S.W.C.]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.108035/-/DC1

References

- Alexandrova A. Y., Arnold K., Schaub S., Vasiliev J. M., Meister J. J., Bershadsky A. D., Verkhovsky A. B. (2008). Comparative dynamics of retrograde actin flow and focal adhesions: formation of nascent adhesions triggers transition from fast to slow flow. PLoS ONE 3, e3234 10.1371/journal.pone.0003234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allingham J. S., Smith R., Rayment I. (2005). The structural basis of blebbistatin inhibition and specificity for myosin II. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 378–379 10.1038/nsmb908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M., Chihara K., Kimura K., Fukata Y., Nakamura N., Matsuura Y., Kaibuchi K. (1997). Formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions enhanced by Rho-kinase. Science 275, 1308–1311 10.1126/science.275.5304.1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aratyn–Schaus Y., Oakes P. W., Gardel M. L. (2011). Dynamic and structural signatures of lamellar actomyosin force generation. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 1330–1339 10.1091/mbc.E10-11-0891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold M., Cavalcanti–Adam E. A., Glass R., Blümmel J., Eck W., Kantlehner M., Kessler H., Spatz J. P. (2004). Activation of integrin function by nanopatterned adhesive interfaces. ChemPhysChem 5, 383–388 10.1002/cphc.200301014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban N. Q., Schwarz U. S., Riveline D., Goichberg P., Tzur G., Sabanay I., Mahalu D., Safran S., Bershadsky A., Addadi L.et al. (2001). Force and focal adhesion assembly: a close relationship studied using elastic micropatterned substrates. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 466–472 10.1038/35074532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beningo K. A., Dembo M., Kaverina I., Small J. V., Wang Y. L. (2001). Nascent focal adhesions are responsible for the generation of strong propulsive forces in migrating fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 153, 881–888 10.1083/jcb.153.4.881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bershadsky A., Kozlov M., Geiger B. (2006). Adhesion-mediated mechanosensitivity: a time to experiment, and a time to theorize. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 472–481 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaouina M., Lad Y., Calderwood D. A. (2008). The N-terminal domains of talin cooperate with the phosphotyrosine binding-like domain to activate β1 and β3 integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6118–6125 10.1074/jbc.M709527200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunch T. A. (2010). Integrin αIIbβ3 activation in Chinese hamster ovary cells and platelets increases clustering rather than affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 1841–1849 10.1074/jbc.M109.057349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K., Chrzanowska–Wodnicka M. (1996). Focal adhesions, contractility, and signaling. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 463–519 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers B. A., Pavlath G. K., Murphy T. J., Karsenty G., García A. J. (2002). Cell-type-dependent up-regulation of in vitro mineralization after overexpression of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor Runx2/Cbfal. J. Bone Miner. Res. 17, 1931–1944 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.11.1931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Biais N., Giannone G., Tanase M., Jiang G., Hofman J. M., Wiggins C. H., Silberzan P., Buguin A., Ladoux B.et al. (2006). Nonmuscle myosin IIA-dependent force inhibits cell spreading and drives F-actin flow. Biophys. J. 91, 3907–3920 10.1529/biophysj.106.084806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood D. A., Ginsberg M. H. (2003). Talin forges the links between integrins and actin. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 694–697 10.1038/ncb0803-694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood D. A., Zent R., Grant R., Rees D. J., Hynes R. O., Ginsberg M. H. (1999). The Talin head domain binds to integrin β subunit cytoplasmic tails and regulates integrin activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 28071–28074 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti–Adam E. A., Micoulet A., Blümmel J., Auernheimer J., Kessler H., Spatz J. P. (2006). Lateral spacing of integrin ligands influences cell spreading and focal adhesion assembly. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 85, 219–224 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti–Adam E. A., Volberg T., Micoulet A., Kessler H., Geiger B., Spatz J. P. (2007). Cell spreading and focal adhesion dynamics are regulated by spacing of integrin ligands. Biophys. J. 92, 2964–2974 10.1529/biophysj.106.089730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Cohen D. M., Choudhury D. M., Kioka N., Craig S. W. (2005). Spatial distribution and functional significance of activated vinculin in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 169, 459–470 10.1083/jcb.200410100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. K., Vicente–Manzanares M., Zareno J., Whitmore L. A., Mogilner A., Horwitz A. R. (2008). Actin and α-actinin orchestrate the assembly and maturation of nascent adhesions in a myosin II motor-independent manner. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1039–1050 10.1038/ncb1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowska–Wodnicka M., Burridge K. (1996). Rho-stimulated contractility drives the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions. J. Cell Biol. 133, 1403–1415 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D. M., Chen H., Johnson R. P., Choudhury B., Craig S. W. (2005). Two distinct head-tail interfaces cooperate to suppress activation of vinculin by talin. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17109–17117 10.1074/jbc.M414704200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D. M., Kutscher B., Chen H., Murphy D. B., Craig S. W. (2006). A conformational switch in vinculin drives formation and dynamics of a talin-vinculin complex at focal adhesions. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 16006–16015 10.1074/jbc.M600738200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussen F., Choquet D., Sheetz M. P., Erickson H. P. (2002). Trimers of the fibronectin cell adhesion domain localize to actin filament bundles and undergo rearward translocation. J. Cell Sci. 115, 2581–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyer S. R., García A. J., Delamarche E. (2007). Facile preparation of complex protein architectures with sub-100 nm resolution on surfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 46, 6837–6840 10.1002/anie.200700989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyer S. R., Delamarche E., García A. J. (2011). Protein tethering into multiscale geometries by covalent subtractive printing. Adv. Mater. 23, 1550–1553 10.1002/adma.201003744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley D. R. (2009). Biochemical and structural properties of the integrin-associated cytoskeletal protein talin. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 38, 235–254 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danen E. H., Sonnenberg A. (2003). Integrins in regulation of tissue development and function. J. Pathol. 201, 632–641 10.1002/path.1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMali K. A., Barlow C. A., Burridge K. (2002). Recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex to vinculin: coupling membrane protrusion to matrix adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 159, 881–891 10.1083/jcb.200206043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumbauld D. W., Shin H., Gallant N. D., Michael K. E., Radhakrishna H., García A. J. (2010). Contractility modulates cell adhesion strengthening through focal adhesion kinase and assembly of vinculin-containing focal adhesions. J. Cell. Physiol. 223, 746–756 10.1002/jcp.22084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler A. J., Sen S., Sweeney H. L., Discher D. E. (2006). Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 126, 677–689 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith C. G., Yamada K. M., Sheetz M. P. (2002). The relationship between force and focal complex development. J. Cell Biol. 159, 695–705 10.1083/jcb.200204153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant N. D., García A. J. (2007). Model of integrin-mediated cell adhesion strengthening. J. Biomech. 40, 1301–1309 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant N. D., Michael K. E., García A. J. (2005). Cell adhesion strengthening: contributions of adhesive area, integrin binding, and focal adhesion assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4329–4340 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García A. J., Takagi J., Boettiger D. (1998a). Two-stage activation for α5β1 integrin binding to surface-adsorbed fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 34710–34715 10.1074/jbc.273.52.34710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García A. J., Huber F., Boettiger D. (1998b). Force required to break α5β1 integrin-fibronectin bonds in intact adherent cells is sensitive to integrin activation state. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10988–10993 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García A. J., Vega M. D., Boettiger D. (1999). Modulation of cell proliferation and differentiation through substrate-dependent changes in fibronectin conformation. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 785–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardel M. L., Sabass B., Ji L., Danuser G., Schwarz U. S., Waterman C. M. (2008). Traction stress in focal adhesions correlates biphasically with actin retrograde flow speed. J. Cell Biol. 183, 999–1005 10.1083/jcb.200810060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardel M. L., Schneider I. C., Aratyn–Schaus Y., Waterman C. M. (2010). Mechanical integration of actin and adhesion dynamics in cell migration. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26, 315–333 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.011209.122036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B., Bershadsky A., Pankov R., Yamada K. M. (2001). Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix and the cytoskeleton. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 793–805 10.1038/35099066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B., Spatz J. P., Bershadsky A. D. (2009). Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 21–33 10.1038/nrm2593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersbach C. A., Le Doux J. M., Guldberg R. E., García A. J. (2006). Inducible regulation of Runx2-stimulated osteogenesis. Gene Ther. 13, 873–882 10.1038/sj.gt.3302725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffin J. M., Pittet P., Csucs G., Lussi J. W., Meister J. J., Hinz B. (2006). Focal adhesion size controls tension-dependent recruitment of α-smooth muscle actin to stress fibers. J. Cell Biol. 172, 259–268 10.1083/jcb.200506179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goult B. T., Bouaouina M., Elliott P. R., Bate N., Patel B., Gingras A. R., Grossmann J. G., Roberts G. C., Calderwood D. A., Critchley D. R.et al. (2010). Structure of a double ubiquitin-like domain in the talin head: a role in integrin activation. EMBO J. 29, 1069–1080 10.1038/emboj.2010.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grashoff C., Hoffman B. D., Brenner M. D., Zhou R., Parsons M., Yang M. T., McLean M. A., Sligar S. G., Chen C. S., Ha T.et al. (2010). Measuring mechanical tension across vinculin reveals regulation of focal adhesion dynamics. Nature 466, 263–266 10.1038/nature09198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin M. A., Sen S., Sweeney H. L., Discher D. E. (2004). Adhesion-contractile balance in myocyte differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5855–5863 10.1242/jcs.01496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries J. D., Wang P., Streuli C., Geiger B., Humphries M. J., Ballestrem C. (2007). Vinculin controls focal adhesion formation by direct interactions with talin and actin. J. Cell Biol. 179, 1043–1057 10.1083/jcb.200703036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R. O. (2002). Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110, 673–687 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00971-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G., Giannone G., Critchley D. R., Fukumoto E., Sheetz M. P. (2003). Two-piconewton slip bond between fibronectin and the cytoskeleton depends on talin. Nature 424, 334–337 10.1038/nature01805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanchanawong P., Shtengel G., Pasapera A. M., Ramko E. B., Davidson M. W., Hess H. F., Waterman C. M. (2010). Nanoscale architecture of integrin-based cell adhesions. Nature 468, 580–584 10.1038/nature09621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keselowsky B. G., García A. J. (2005). Quantitative methods for analysis of integrin binding and focal adhesion formation on biomaterial surfaces. Biomaterials 26, 413–418 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo L. Y., Irvine D. J., Mayes A. M., Lauffenburger D. A., Griffith L. G. (2002). Co-regulation of cell adhesion by nanoscale RGD organization and mechanical stimulus. J. Cell Sci. 115, 1423–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo J. C., Han X., Hsiao C. T., Yates J. R., 3rd, Waterman C. M. (2011). Analysis of the myosin-II-responsive focal adhesion proteome reveals a role for β-Pix in negative regulation of focal adhesion maturation. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 383–393 10.1038/ncb2216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert D., Wehrle–Haller B., David C., Weiland U., Ballestrem C., Imhof B. A., Bastmeyer M. (2004). Cell behaviour on micropatterned substrata: limits of extracellular matrix geometry for spreading and adhesion. J. Cell Sci. 117, 41–52 10.1242/jcs.00836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari G., Brown G., Lauffenburger D. A., Wells A., Griffith L. G. (2000). Cell adhesion and motility depend on nanoscale RGD clustering. J. Cell Sci. 113, 1677–1686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massia S. P., Hubbell J. A. (1991). An RGD spacing of 440 nm is sufficient for integrin αvβ3-mediated fibroblast spreading and 140 nm for focal contact and stress fiber formation. J. Cell Biol. 114, 1089–1100 10.1083/jcb.114.5.1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael K. E., Dumbauld D. W., Burns K. L., Hanks S. K., García A. J. (2009). Focal adhesion kinase modulates cell adhesion strengthening via integrin activation. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 2508–2519 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S., Akiyama S. K., Yamada K. M. (1995a). Synergistic roles for receptor occupancy and aggregation in integrin transmembrane function. Science 267, 883–885 10.1126/science.7846531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S., Teramoto H., Coso O. A., Gutkind J. S., Burbelo P. D., Akiyama S. K., Yamada K. M. (1995b). Integrin function: molecular hierarchies of cytoskeletal and signaling molecules. J. Cell Biol. 131, 791–805 10.1083/jcb.131.3.791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson C. M., Jean R. P., Tan J. L., Liu W. F., Sniadecki N. J., Spector A. A., Chen C. S. (2005). Emergent patterns of growth controlled by multicellular form and mechanics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11594–11599 10.1073/pnas.0502575102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson C. M., Vanduijn M. M., Inman J. L., Fletcher D. A., Bissell M. J. (2006). Tissue geometry determines sites of mammary branching morphogenesis in organotypic cultures. Science 314, 298–300 10.1126/science.1131000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J. T., Horwitz A. R., Schwartz M. A. (2010). Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 633–643 10.1038/nrm2957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie T. A., Raynor J. E., Dumbauld D. W., Lee T. T., Jagtap S., Templeman K. L., Collard D. M., García A. J. (2010). Multivalent integrin-specific ligands enhance tissue healing and biomaterial integration. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, 45ra60 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riveline D., Zamir E., Balaban N. Q., Schwarz U. S., Ishizaki T., Narumiya S., Kam Z., Geiger B., Bershadsky A. D. (2001). Focal contacts as mechanosensors: externally applied local mechanical force induces growth of focal contacts by an mDia1-dependent and ROCK-independent mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 153, 1175–1186 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca–Cusachs P., Gauthier N. C., Del Rio A., Sheetz M. P. (2009). Clustering of α5β1 integrins determines adhesion strength whereas αvβ3 and talin enable mechanotransduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 16245–16250 10.1073/pnas.0902818106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier O. M., Gauthier N., Biais N., Vonnegut W., Fardin M. A., Avigan P., Heller E. R., Mathur A., Ghassemi S., Koeckert M. S.et al. (2010). Force generated by actomyosin contraction builds bridges between adhesive contacts. EMBO J. 29, 1055–1068 10.1038/emboj.2010.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selhuber–Unkel C., Erdmann T., López–García M., Kessler H., Schwarz U. S., Spatz J. P. (2010). Cell adhesion strength is controlled by intermolecular spacing of adhesion receptors. Biophys. J. 98, 543–551 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattil S. J., Kim C., Ginsberg M. H. (2010). The final steps of integrin activation: the end game. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 288–300 10.1038/nrm2871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniadecki N. J., Desai R. A., Ruiz S. A., Chen C. S. (2006). Nanotechnology for cell-substrate interactions. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 34, 59–74 10.1007/s10439-005-9006-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stricker J., Aratyn–Schaus Y., Oakes P. W., Gardel M. L. (2011). Spatiotemporal constraints on the force-dependent growth of focal adhesions. Biophys. J. 100, 2883–2893 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro S., Shattil S. J., Eto K., Tai V., Liddington R. C., de Pereda J. M., Ginsberg M. H., Calderwood D. A. (2003). Talin binding to integrin β tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science 302, 103–106 10.1126/science.1086652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J. L., Tien J., Pirone D. M., Gray D. S., Bhadriraju K., Chen C. S. (2003). Cells lying on a bed of microneedles: an approach to isolate mechanical force. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1484–1489 10.1073/pnas.0235407100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]