Abstract

It has recently been shown that RNA 3′ end formation plays a more widespread role in controlling gene expression than previously thought. In order to examine the impact of regulated 3′ end formation genome-wide we applied direct RNA sequencing to A. thaliana. Here we show the authentic transcriptome in unprecedented detail and how 3′ end formation impacts genome organization. We reveal extreme heterogeneity in RNA 3′ ends, discover previously unrecognized non-coding RNAs and propose widespread re-annotation of the genome. We explain the origin of most poly(A)+ antisense RNAs and identify cis-elements that control 3′ end formation in different registers. These findings are essential to understand what the genome actually encodes, how it is organized and the impact of regulated 3′ end formation on these processes.

Introduction

Arabidopsis thaliana is an important model system that has played a critical role in discoveries essential to our understanding of plant biology and generically important processes such as RNA interference (RNAi). Although the A. thaliana genome was sequenced more than a decade ago, challenges remain to resolve the RNAs that it encodes and to determine their functional significance. Establishing where transcripts end is essential in genome annotation and for understanding gene function. Alternative cleavage and polyadenylation (APA) defines different 3′ ends within pre-mRNA transcribed from the same gene, and this can affect function by determining coding potential or the inclusion of regulatory sequence elements1,2. This regulation of RNA 3′ end formation is considerably more widespread than previously thought1,2 and RNA binding proteins which enable A. thaliana flowering provide important examples of the biological impact of this control3. Defective 3′ end formation and transcription termination at tandem or convergent gene pairs can result in transcription interference or RNAi4,5, revealing that these processes normally partition the genome and maintain expression of neighboring genes6. Accordingly, such consequences of uncontrolled 3′ end formation also emphasize the critical nature of gene arrangement along a eukaryotic chromosome.

As a prelude to the analysis of regulators of 3′ end formation, we set out to map A. thaliana RNA 3′ ends genome-wide. Previous high-throughput A. thaliana transcriptome studies have depended on the copying of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) with reverse transcriptase7-10. However, the intrinsic template switching11 and DNA-dependent DNA polymerase12 activities of reverse transcriptases, together with oligo(dT)-dependent internal priming13, cause well-established artifacts that can affect the identification of authentic antisense RNAs14,15, splicing events14 and RNA 3′ ends13,16. Different strategies have been developed to address these problems, making strand-specific RNA sequencing an increasingly powerful tool for the analysis of transcriptomes. However, a recent comparison of several such methods showed marked differences, not only in strand specificity, but also in a range of criteria that influence transcriptome interpretation17. Therefore, as an alternative, we used Direct RNA Sequencing (DRS) to identify polyadenylated A. thaliana RNAs18. This approach is direct in the sense that native RNA is used as the sequencing template, but the sequence is read by imaging complementary fluorescent nucleotides incorporated by a polymerase. In this true single molecule sequencing (tSMS) procedure the site of RNA cleavage and polyadenylation is defined with an accuracy of ± 2nt in the absence of errors induced by reverse transcriptase, ligation or amplification18.

Results

Mapping A. thaliana RNA 3′ ends

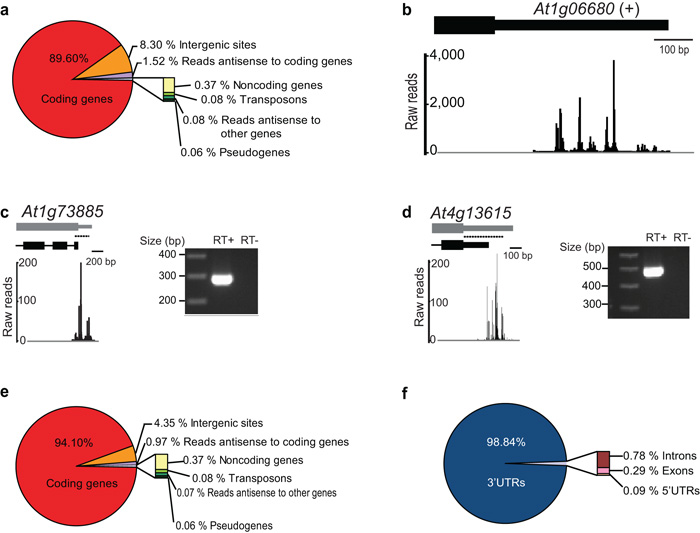

Total RNA purified from A. thaliana seedlings was subjected to DRS and a computational procedure to align reads uniquely to the most recent A. thaliana genome release (TAIR10) was developed. The initial mapping analysis revealed that the vast majority of reads (89.60%) aligned to protein-coding genes which is consistent with the idea that this approach can identify authentic sites of mRNA cleavage and polyadenylation (Fig. 1a). These data define extremely heterogeneous patterns of RNA 3′ end formation (Fig. 1b) that differ markedly from human mRNAs analyzed in the same way (Supplementary Fig. 1a)18.

Figure 1. Genome-Wide Patterns of A. thaliana RNA 3′ End Formation.

(a) Genome-wide distribution of DRS reads before re-annotation. (b) Example of DRS alignment to an annotated 3′UTR showing extreme heterogeneity of cleavage sites. Exons are denoted by rectangles and UTRs by adjoining narrower rectangles. (c, d) comparison of TAIR10 (black) and proposed DRS-dependent (grey) annotations for At1g73885 (a previously undefined 3′UTR) and At4g13615 (an extended 3′UTR). RT-PCR with amplicons denoted by dashed lines shows evidence of contiguous RNAs. (e) Genome-wide distribution of DRS reads after re-annotation. (f) Distribution of DRS reads mapping to protein-coding genes after re-annotation.

Although non-templated base addition between cleavage sites and the poly(A) tail has been reported from analysis of A. thaliana expressed sequence tag (EST) data19, we found no evidence for this phenomenon in our DRS data, suggesting it is an artifact of reverse transcriptase-dependent library construction (Supplementary Table 1).

Initially, 8.30% of reads were mapped to intergenic regions (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 2), but they showed a clear non-random distribution with most aligning within 300 nucleotides downstream of annotated genes (Supplementary Fig. 1b). For some genes that lacked annotated 3′UTRs the reads aligned immediately downstream (Fig. 1c), while for others the aligned reads extended beyond annotated 3′ ends (Fig. 1d). Accordingly, we asked whether these apparently intergenic reads defined authentic, but previously unrecognized, 3′UTRs. Consistent with this idea, we found evidence of contiguous RNAs using RT-PCR (Fig. 1c,d) and 3′RACE (Supplementary Fig. 1c,d) with one primer anchored in annotated sequence and another targeted either to downstream sequence identified by intergenic DRS reads or poly(A) sequence (in 3′RACE). We developed data smoothing and peak-finding algorithms to address systematically the genome-wide annotation of 3′ ends (Supplementary Fig. 2a). This process led us to propose the first 3′ annotation of 165 genes (Supplementary Table 3) and re-annotation (by extension) of 10,215 A. thaliana protein-coding genes, of which 3,427 were extended by 10 or more nucleotides (Supplementary Table 4). Sequencing to greater depth is likely to lead to further re-annotation. A small number of reads initially mapped to 5′UTRs but, following re-annotation of 3′ ends by extension, almost all of these appeared to comprise the 3′ ends of overlapping tandemly arranged genes (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Re-annotating the 3′ ends of A. thaliana genes in these ways accounted for 48% of intergenic reads, so that 94.10% of all reads could be attributed to A. thaliana protein-coding genes (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Table 2). The remaining intergenic reads provide a useful resource for the identification of previously undiscovered genes or poly(A)+ RNAs.

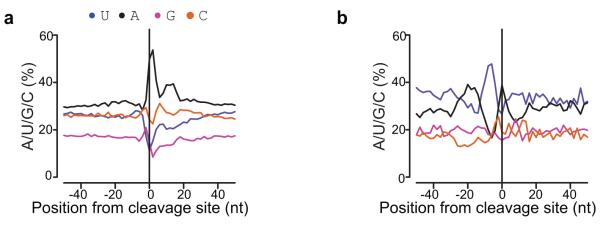

Internal oligo(dT) Priming is Rare or Absent in DRS

Of all reads mapping to protein-coding genes, 98.84% mapped to 3′UTRs (Fig. 1f). These findings contrast with previous massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) data7 and recent oligo(dT)-primed Illumina cDNA sequencing results10 that have been interpreted to show that a large class of A. thaliana mRNAs are cleaved in coding sequence exons10. DRS, which lacks oligo(dT)-dependent reverse transcriptase priming, provided no evidence for this novel class of RNAs, suggesting it is an artifact resulting from internal priming on A-rich sequences. 90.5% of such sites detected by Wu et al.10 were not supported by DRS reads, even though the DRS dataset was larger and expression of exemplar transcripts reported to have coding exon cleavage sites was readily detected (Supplementary Table 5). We analyzed the nucleotide composition around this subset of sites and found no clear sequence bias upstream of the aligned reads, but distinct enrichment of A (and G) residues immediately downstream, a profile consistent with internal priming (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the remaining 9.5% of sites that did have DRS support showed a nucleotide profile (Fig. 2b) similar to that derived for A. thaliana 3′UTRs20 (and see below), suggesting they reflect genuine cleavage sites. Closer inspection of these rare reads (0.04% of all reads) indicates that their classification as coding exons may be erroneous and explained by incomplete annotation in TAIR10: 70% of such reads map to the last coding exon adjacent to 3′UTRs, while others map to alternatively spliced sequences that constitute a coding exon in one isoform, but intronic sequence in another.

Figure 2. Internal Priming is Rare or Absent in DRS.

Nucleotide composition plots around proposed cleavage sites deduced from reads mapping to coding sequence exons reported by Wu at al.10 either without (a) or with (b) DRS confirmation. The 90.5% of sites without DRS support (a) show a nucleotide profile consistent with them being artifacts resulting from internal priming. In contrast, the 9.5% of sites with DRS support show an alternating pattern of A and U-rich sequence characteristic of A. thaliana 3′UTRs.

To address the issue of internal priming in a different way, we investigated whether potential internal priming substrates (consisting of six or more consecutive As) were detected in our dataset. There were 25,590 such sequences in 11,246 expressed genes (having 10 or more DRS reads). Since DRS detects the position of 3′ ends with an accuracy of ± 2nt18, to be conservative, we asked how many such sites were matched with 10 or more DRS reads aligned within a 10 nucleotide window upstream. Only 4% of such sites (1024 A≥6 sequences in 983 genes) were matched with DRS reads using these criteria. Since the vast majority of these (97%) mapped to 3′UTRs (996 A≥6 sequences in 959 genes), they may identify authentic 3′ ends. 20,972 A≥6 sequences were found in either the coding sequence or the 5′UTR of 9730 genes expressed in this dataset and so may more readily be identified as potential internal priming substrates. Of these, only 0.13% (27 A≥6 sequences in 27 genes) had 10 or more DRS reads mapping within 10 nucleotides upstream. Finally, of relevance to this issue, our sequencing was performed on total RNA preparations in which the abundance of RNA species is dominated by nuclear and plastid encoded ribosomal RNAs. However, although mitochondrial 26S rRNA (AtMg00020) contains an A6 region, no reads aligning to this sequence were found.

These data underscore the fact that internal priming confounds oligo(dT)-primed analysis of polyadenylated cleavage sites16. Filtering of such datasets to remove sequences that align upstream of genome-encoded A-rich regions is routinely done10,21 (and indeed was done by Wu et al.10), but as we show here, and others have recently shown16, this is insufficient to exclude all internal priming events and is problematic because it may remove authentic 3′ ends from analysis. We conclude that internal priming is rare or absent in DRS and as a result we did not filter any of our uniquely aligned reads from further analyses.

Cleavage and Polyadenylation Within pre-mRNA Introns is Rare

Sequences aligning to pre-mRNA introns were relatively rare (Fig. 1f) and in many cases, comprised only 1–2 reads. When we restricted analysis to expression levels that could be detected by our peak-finding algorithm, cleavage sites within introns located upstream of 3′UTRs were found in 104 protein-coding genes, including the sites of alternative polyadenylation that effect autoregulation of the flowering regulators FCA and FPA3 (Supplementary Table 6, Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). Cleavage sites within introns located in 3′UTRs were found in 114 protein-coding genes (Supplementary Fig. 3c, Supplementary Table 7), indicating that such introns are more likely to be sites of alternative cleavage and polyadenylation than are all other introns combined. Since the splicing of introns within 3′UTRs can affect 3′UTR length and lead to nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD), alternative polyadenylation/splicing in these pre-mRNAs may be of regulatory significance22.

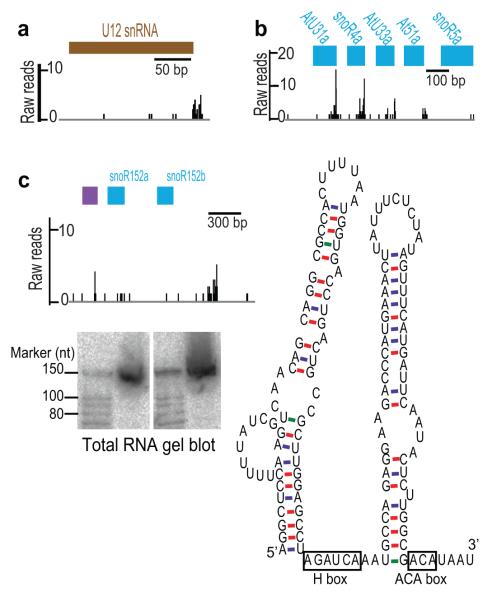

Identification of Poly(A)+ Exosome Target RNAs

Although the vast majority of reads aligned to protein-coding gene 3′UTRs, we also detected reads (0.37% of all reads) that aligned to non-coding RNAs, such as rRNA, snRNAs and snoRNAs (but not tRNAs) transcribed by RNA polymerase I, II or III (see Fig. 3a,b, for examples). As these RNAs are established targets of the exosome it was possible that RNAs oligoadenylated by the Trf4/Trf5-Air1/Air2-Mtr4 polyadenylation (TRAMP) complex for exosome processing23 were being detected in addition to mRNAs polyadenylated by the cleavage and polyadenylation machinery. This was unexpected because the rapid processing/decay mediated by the exosome means that targets are usually only detected in genetic backgrounds defective in exosome function24.

Figure 3. Identification of Un-annotated or Previously Undetected ncRNAs.

(a) Reads mapping to the locus encoding U12 snRNA. (b) Reads mapping to a known snoRNA cluster. (c) SnoSeeker-predicted H/ACA snoRNA (purple) found in the known snoR152a/snoR152b (blue) cluster and validated by RNA gel blot analysis. The secondary structure prediction (ViennaRNA-1.8.4), and the position of box H and ACA sequences consistent with this class of snoRNA are indicated.

A. thaliana snoRNA loci are often organized in polycistronic clusters located in either intergenic regions or the introns of protein-coding genes25. We found reads that often (but not always) aligned to the 3′ end of each annotated snoRNA in a cluster (Fig. 3b), consistent with the idea that they identified 3′ trimming of precursor RNAs. We also observed adjacent reads with no corresponding annotation, raising the possibility that we were detecting un-annotated snoRNAs. The complement of A. thaliana snoRNAs is relatively poorly defined (only 71 are annotated in TAIR10). We developed our own annotation of published A. thaliana snoRNAs, totaling 287 snoRNA genes and found DRS reads that matched almost every one (Supplementary Table 8). We detected reads exclusively associated with the snoRNA moiety of dicistronic tRNA–snoRNAs that are apparently unique to plants (Supplementary Fig. 4a), suggesting that maturation of snoRNA, but not tRNA, from these precursors involves exosome processing. We then ran snoRNA prediction programs to determine whether further DRS reads within clusters might correspond to previously unrecognized snoRNAs and validated expression of a specific example by RNA gel blot analysis (Fig. 3c). Therefore DRS can aid the identification of ncRNAs that have not previously been discovered or annotated within TAIR10.

We used RT-PCR to confirm we were indeed detecting snoRNA processing intermediates: Evidence of contiguous RNAs between the site of DRS reads and upstream snoRNAs, consistent with snoRNA processing intermediates, was obtained using primers targeted to each such sequence (Supplementary Fig. 4a-f). Analysis of the nucleotide profiles adjacent to cleavage sites at snoRNAs revealed a pattern that contrasted markedly with that at cleavage sites found in protein coding genes (Supplementary Fig. 5a,b). These findings are consistent with the cis-elements and processing activities that generate polyadenylated RNAs at A. thaliana snoRNAs and pre-mRNAs being different.

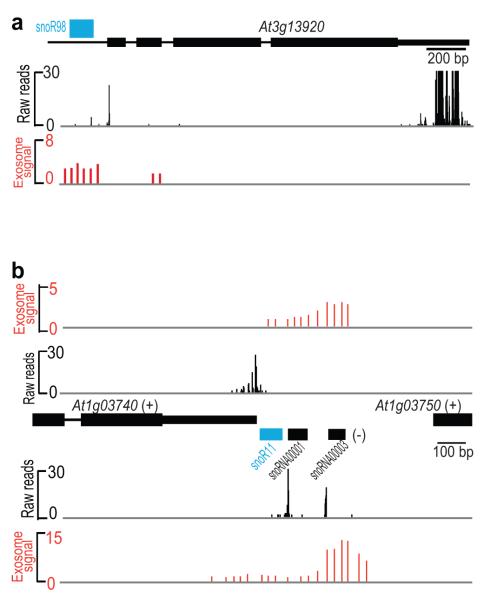

We aligned previous tiling array analysis of A. thaliana exosome subunit knockdown lines24 with our DRS data, incorporating our updated snoRNA annotation. This showed that many open reading frames previously proposed to be regulated by the exosome24 actually corresponded to un-annotated snoRNAs (Fig. 4a), raising the likelihood that snoRNA processing and not protein-coding gene regulation explains exosome activity at these loci. We also found widespread occurrences of DRS reads aligning only to one strand, whereas the exosome data aligned to both. Since DRS does not involve reverse transcription, it unequivocally determines the RNA strand of origin. Thus, an example of a gene (At1g03740) for which the exosome was proposed to affect RNA 3′ end formation24 may actually be explained by processing of snoRNAs coded on the other strand (Fig. 4b). Artifacts resulting from the combined use of reverse transcriptase and tiling arrays may account for these distinguishing observations12,14,15,26,27 and suggests a need to reassess our current understanding of A. thaliana exosome targets. We conclude that DRS can identify polyadenylated decay intermediates for exosome processing, but that these represent a very small proportion of the poly(A)+ RNA of A. thaliana seedlings.

Figure 4. Identification of ncRNAs at Sites Affected by the Exosome.

(a) Comparison of DRS reads (black) with exosome knockdown array data (red) for the At3g13920 open reading frame, suggested to be regulated by the exosome24, which also encodes a known but un-annotated snoRNA (blue). (b) Comparison of DRS reads (black) with exosome knockdown array data (red) showing differences in strand specificity. The previously proposed role of the exosome in controlling 3′ end formation at At1g03740 may now be explained by processing of snoRNAs that are not annotated (blue) or annotated (black) in TAIR10 on the other strand and artifacts resulting from reverse transcriptase and tiling arrays.

Antisense Poly(A)+ RNA from Convergent Gene Pairs

DRS provides quantitative data on the sites of sense and antisense transcription in the absence of errors inherent to reverse transcription18. Previous estimates of A. thaliana antisense expression from different genome-wide tiling array platforms reported polyadenylated antisense RNA at either 7,6008 or 12,0909 A. thaliana genes. In contrast, we detected antisense expression (10 reads or more) at only 3,213 protein-coding genes. This discrepancy may be explained in part because our focus on 3′ ends means we do not identify transcripts from divergent gene pairs that overlap at their 5′ ends. In addition, some antisense RNAs may have been mis-scored because of artifacts arising from the use of reverse-transcriptase and tiling arrays12,14,15,26. Further strand-specific RNA sequencing, not limited to 3′ ends, should resolve this issue.

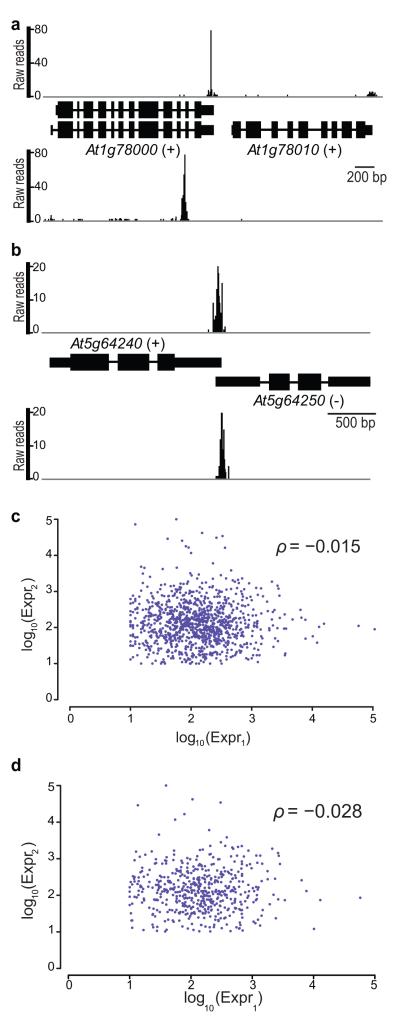

Intergenic reads that mapped antisense to annotated coding genes accounted for 0.97% of all reads (Figs. 1f, 5a). When we also considered reads that aligned to 3′UTRs, we found that 17.5% of all reads mapped to annotated convergent overlapping gene pairs (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Table 9), corresponding to 1,581 pairs of protein-coding genes. Of these, we detected overlapping expression at both genes in 593 pairs. In the vast majority of these pairs (524) overlapping expression was restricted to 3′UTRs, with a median overlap distance of 47 nucleotides. As there is potential for this gene architecture to lead to transcription interference, or RNAi, one might predict mutually exclusive expression of each gene in such pairs. However, when the expression of annotated overlapping gene pairs is compared, the Spearman correlation coefficient of −0.015 shows no support for anti-correlated expression (Fig. 5c). Likewise, when the expression of only the sub-set with overlap deduced from DRS reads mapping to each gene in a pair was considered, the Spearman correlation coefficient was only −0.028 (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5. Most Antisense Expression Derives from Convergent Gene Pairs with Overlapping 3′UTRs.

(a) Example of intergenic DRS reads mapping antisense to a coding gene. The upper panel shows reads mapping to the (+) strand 3′ end of At1g78000 and At1g78010, while the lower panel shows intergenic reads (i.e. reads that don’t align to an annotated genome feature) antisense to At1g78000. (b) Example of reads mapping to 3′UTRs of a convergent overlapping gene pair. (c) Scatterplot of coding gene log10 expression for all convergent gene pairs in TAIR10 with 10 or more reads per gene. The Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ = −0.015) shows no evidence of anti-correlated expression. (d) Scatterplot of coding gene log10 expression for all convergent gene pairs with overlap detected by our peak finding algorithm (524 pairs). The Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ = −0.028) also shows no evidence of anti-correlated expression.

A sub-set of Drosophila melanogaster convergent gene pairs that overlap at their 3′ end are associated with siRNAs that match the site of overlap, but evidence of their regulatory impact is equivocal28. The paradigm for siRNA mediated anti-correlated expression of convergent overlapping gene pairs, or cis-natural antisense transcripts, comes from A. thaliana SRO5 (At5g62520) and P5CDH (At5g62530)29. However, we found the sites of RNA 3′ end formation at each of these genes differ markedly from those annotated in TAIR10 and previously reported29. As a consequence, we found no evidence that these RNAs overlap in the region from which siRNAs were reported to derive (Supplementary Fig. 6a) and we suggest the siRNA-induced 3′ cleavage product of P5CDH identified by Borsani et al.29 is mis-assigned because the probe used would not detect P5CDH, but SRO5 instead (Supplementary Fig. 6a)29. Our findings are also inconsistent with the other key A. thaliana example of siRNA mediated anti-correlated gene expression involving the convergent gene pair AtGB2 (At4g35860) and PPRL (At4g35850)30. In this case, an siRNA was proposed to mediate down regulation of PPRL through its complementarity to the PPRL 3′UTR30. However, our data, consistent with the current TAIR10 annotation, provides no evidence for such an overlap (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Importantly, we extend previous studies on cis-natural antisense transcripts because we provide the first definitive dataset on the site of 3′ end formation, defining overlap without depending on genome annotation, while simultaneously quantifying gene expression levels. From these data, we do not detect a general trend of anti-correlated expression at these gene pairs. This does not rule out the possibility that regulatory effects occur at such loci in specific circumstances, but we suggest that previous reports documenting examples of siRNA-mediated anti-correlated expression in A. thaliana should be carefully re-examined29,30.

Rather than anti-correlated expression, another possibility is that transcription interference or RNAi may dampen expression of both genes in convergently overlapping gene pairs. However, average expression at such gene pairs was actually higher than at other genes: a mean of 599 reads at the 1048 genes in the overlapping gene pairs compared to 468 reads for single genes. This difference was statistically significant, as judged by a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p-value=0.0014; 524 convergent overlapping pairs compared with 12024 other genes where expression was detected by our peak finding algorithm).

Overall, we conclude that polyadenylated antisense RNA expression is a smaller constituent of the A. thaliana transcriptome than was recently proposed and that convergent gene pairs with overlapping 3′UTRs explain most poly(A)+ antisense RNA expression. There is no general trend associating this genome architecture with down-regulated gene expression, but this analysis does not rule out the possibility that such regulation might occur at specific sites in certain conditions.

Dual-Use poly(A) Signals in A. thaliana 3′UTRs

The extreme heterogeneity of RNA 3′ ends raises questions as to how A. thaliana mRNA 3′ ends form: for example, do specific sequences guide processing or is cleavage stochastic? Furthermore, how does 3′ end formation occur in convergent gene pairs with overlapping 3′UTRs? Since our dataset is the deepest and most accurate view of transcript structure available, we asked whether the analysis of these data could bring new insight to these questions. Since DRS provides a quantitative measure of RNA expression, we were able to make the first identification of preferred sites of 3′ end formation by application of our peak-finding algorithm (Supplementary Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 10), classifying the most frequently used cleavage sites in each 3′UTR, the second most frequently used and so on (making the assumption that abundance reflects preference). This analysis shows that 74.90% of protein-coding genes expressed in these conditions have multiple alternative 3′ ends, but that most reads (59%) are associated with a preferred cleavage site.

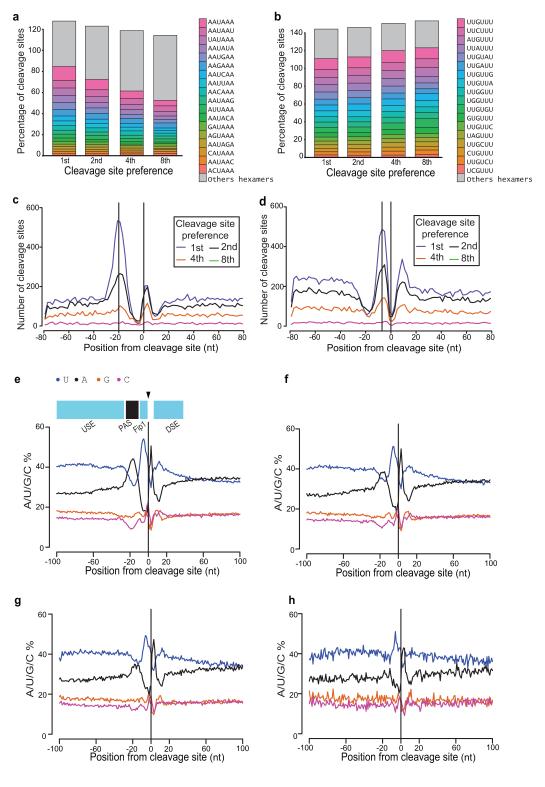

We analyzed the sequence features associated with these cleavage sites in two ways. First, we identified sequence motifs enriched nearby and second, we analyzed the nucleotide preference profiles around cleavage sites. The most common motif associated with preferred sites was AAUAAA (Fig. 6a), with its distribution peaking 19 nucleotides upstream of the cleavage site (Supplementary Fig. 7a) exactly matching the canonical metazoan poly(A) signal in sequence and position2. A U-rich motif UUGUUU (Fig. 6b), located seven nucleotides upstream of the cleavage site (Supplementary Fig. 7b) was also found. Although most prominent, these particular motifs were found upstream of a relatively small fraction of cleavage sites, but related hexamers differing at only a single position (except AAAAAA and UUUUUU) showed similar distribution patterns (Fig. 6c,d). This distribution of motifs was reflected in the nucleotide preference profiles adjacent to preferred cleavage sites (1st) which reveal an alternating pattern of U and A-rich sequences that correspond to U-rich upstream sequence elements (USE), the A-rich poly(A) signal (PAS) peaking at −20, the UUGUUU-like motif at −7 (that might be a binding site for the conserved cleavage and polyadenylation factor Fip116,31), a short A-rich sequence, and U-rich sequence (DSE) downstream of the cleavage site (Fig. 6e-h).

Figure 6. Cis-Element Analysis at Cleavage Sites.

(a,b) Fraction of cleavage sites with AAUAAA-like and UUGUUU-like hexamers found within a 50-nucleotide region upstream: (a) AAUAAA and 17 single point mutation hexamers (AAAAAA excluded); (b) UUGUUU and 17 single point mutation hexamers (UUUUUU excluded). The total sum of all fractions exceeds 100% because some cleavage sites have more than one such hexamer within the upstream region. The cleavage sites are classified by preference of usage: 1st (most preferred, i.e. corresponding to the site with largest amount of DRS reads mapped to it) through to 8th (least preferred) in a given 3′UTR. (c) Distribution of AAUAAA-like motifs relative to preferred cleavage site. (d) Distribution of UUGUUU-like motifs relative to preferred cleavage site. (e-h) Nucleotide composition profiles around cleavage sites ranked by preference of usage: 1st (most preferred) through to 8th (least preferred) indicating that preferred and non-preferred sites in a 3′UTR are associated with different sequences. The proposed designation of alternating U- and A-rich sequences at preferred cleavage sites is shown in (e): USE (upstream sequence element), PAS (poly(A) signal), the U-rich sequencing upstream of the cleavage site has been proposed to be the binding site of FIP116 and while this remains to be clearly established this labeling is useful for distinguishing different U-rich sequences, DSE (downstream sequence element).

AAUAAA-like and UUGUUU-like sequences were not found upstream of all preferred cleavage sites (Fig. 6a,b). Nevertheless, nucleotide profile plots of sequences around preferred sites that lack these motifs still showed the same alternating pattern of U and A-rich sequences (Supplementary Fig. 7c–f), suggesting that they comprise closely related sequences that differ from these motifs at more than one position. In contrast, the distinguishing feature of non-preferred sites was the absence of an AAUAAA-like A-rich peak at −20 (Fig. 6a;e–h). These data indicate that preferred and non-preferred sites in a 3′UTR are associated with different cis-element sequences.

This pattern of alternating U- and A-rich sequences closely resembles the one recently defined for Caenorhabditis elegans, which was proposed to encode poly(A) signals in different registers within the same 3′UTR16. In A. thaliana, this sequence organization may similarly explain heterogeneity in 3′ end formation and the occurrence of convergent gene pairs with overlapping 3′UTRs. For example, we found that the nucleotide profiles around neighboring cleavage sites in the same 3′UTR, which peaked at a distance of 15–20 nucleotides apart (Fig. 7a), showed phasing of the A- and U-rich sequences in a manner consistent with them performing dual functions as distinct elements within overlapping poly(A) signals (Fig. 7b). When we examined convergent overlapping gene pairs, we found that the distance from sense-strand cleavage sites to cleavage sites on antisense RNA strands peaked at −6 to +4 nucleotides and at −15 to −25 nucleotides (Fig. 7c). The phasing in these instances enables, for example, A-rich poly(A) signal sequences on one strand to function as U-rich cis-elements guiding cleavage on the other (Fig. 7d).

Figure 7. Multifunctional Cis-Elements within the Same 3′UTR.

(a) Distance between cleavage sites in the same 3′UTR with peaks in distribution of adjacent sites marked by colored bands. (b) Nucleotide composition plots for adjacent sites located 15–20 nucleotides (left plot) or 35–40 nucleotides (right plot) apart. (c) Distance between cleavage sites in sense and antisense 3′UTRs of convergent gene pairs with peaks in distribution of adjacent sites marked by colored bands. (d) Nucleotide composition plots for adjacent sense and antisense cleavage sites peaking at −25 to −15 nucleotides (left plot) or−6 to +4 nucleotides (right plot).

Therefore, this analysis reveals that although extremely heterogeneous, 3′ end formation is not stochastic, since most preferred sites of A. thaliana mRNA cleavage and polyadenylation are associated with clearly identifiable poly(A) signals and nucleotide profiles that are highly reminiscent of metazoan mRNA 3′UTRs. The multi-purpose functionality of these A- and U-rich sequence elements in A. thaliana 3′UTRs may account for the relative looseness of the consensus sequences derived for them compared to human poly(A) signals. However, this may also provide robustness to 3′ end formation within the same 3′UTR, effective at multiple heterogeneous sites, and facilitate genome compaction by eliminating intergenic sequence.

Discussion

Previously, the RNA 3′ ends of the model organism, A. thaliana, were poorly characterized, but defining the sites of 3′ end formation is essential for genome annotation and to understand the regulation of gene expression. We resolved the heterogeneity in 3′ end formation using quantitative DRS data to analyze cleavage sites separately, based on preference. This led to an understanding of A. thaliana 3′UTRs and 3′ end formation that is consistent with the detailed experimental dissection of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) poly(A) signal carried out by Hohn and co-workers: these analyses identified a U-rich upstream sequence element that enhanced 3′ end formation32 and showed that while each possible point mutation to the AAUAAA hexamer could be tolerated32, deletion of this hexamer abolished 3′ end formation33. At the time, this experimental work could not be generalized to other plant 3′UTRs. This is largely explained by our analysis, which reveals that 3′ end formation within the same 3′UTR is extremely heterogeneous; quantitative differences in cleavage site preference are associated with multifunctional overlapping poly(A) signals of relatively loosely defined sequence; and accurate and efficient 3′ end formation is combinatorial. As a result, the density and complexity of overlapping functional poly(A) signals in each A. thaliana 3′UTR makes the identification of sequences corresponding to those of the CaMV poly(A) signal difficult, if not impossible.

Alternative cleavage and polyadenylation within human 3′UTRs is intimately connected to miRNA-mediated regulation as human miRNA target sites are mostly found in 3′UTRs34-36. In contrast, A. thaliana miRNA target sites are generally found in open reading frames35. This distinction likely relates to differences in the extent of miRNA-target base-pairing and the resulting sensitivity of such duplexes to translocating ribosomes36. We speculate that the heterogeneity of RNA 3′ end formation we detect here may preclude robust miRNA-mediated regulation targeted to A. thaliana 3′UTRs. As a result, an interplay between differences in mRNA 3′ end formation and miRNA targeting may have contributed to the evolution of current target site distinctions.

We discovered that most poly(A)+ antisense RNAs derive from convergent gene pairs with overlap restricted to their 3′UTRs. One might expect such a gene arrangement to be rare because of the potential for either transcription interference or RNAi to compromise gene expression4,5,37. However, nearly one fifth of all our DRS reads derived from such gene pairs and we found no general trend of either anti-correlated or relatively reduced expression at these loci in our dataset. This might be because the seedling RNA we analyzed is derived from multiple cell types where transcription at convergent overlapping gene pairs could be spatially separated. Alternatively, depending on either allele-specific expression, or pulses of transcription, endogenous overlapping gene pairs may not necessarily be subject to transcription interference or RNAi. Expression of similar 3′ convergent gene pairs in the same cell type has been detected in D. melanogaster without resultant RNAi28. Previous analyses of A. thaliana convergent gene pair expression, albeit with less definitive datasets, also found no evidence of their regulation by RNAi38,39. These findings stand in contrast to the paradigm of siRNA-dependent anti-correlated expression defined for the convergent gene pair SRO5/P5CDH29. However, our analysis casts doubt on the robustness of the data presented in that study suggesting that the conclusions should be revisited. Regardless, what is clear is that the convergent overlapping gene pairs identified here share 3′UTRs. Rather than being avoided, this genomic architecture may be favored because it drives genome compaction through the elimination of intergenic sequence. Our analysis indicates that the multi-functionality of U- and A-rich poly(A) signals enables this arrangement by facilitating 3′ end formation in sense and antisense RNAs. Since this is consistent with the recent analysis of C. elegans 3′UTRs16, this influence of 3′ end formation on genome organization may be quite general. It will be interesting to apply DRS to related species with larger or polyploid sequenced genomes to address whether shared 3′UTRs are restricted to compact genomes and select against transposon insertion. Additionally, we found mean expression levels at these overlapping gene pairs to be higher than at other genes. Perhaps, physical interactions between promoter and 3′ end regions (gene loops) juxtapose the promoters of convergent gene pairs with the same terminator creating a nexus that facilitates local recycling of factors essential for transcription2,40.

We show that DRS avoids internal priming problems that confound oligo(dT) primed analyses of polyadenylated cleavage sites. Presumably, the environment of the sequencing flow-cell favors annealing of the 3′ poly(A) tail over intramolecular A-rich sequences. DRS obviates not only problems associated with reverse transcription12,14,15, but also the complex sample preparation and amplification that can affect quantification of RNA-seq data41. DRS has limitations too, since read-lengths are relatively short and indels may affect read alignments. Nevertheless, DRS should be a useful addition not only to the study of regulated 3′ end formation between samples, but other aspects of transcriptome analysis too. Overall, our findings suggest that viewing gene expression by sequencing RNA directly, rather than through the prism of reverse transcriptase-dependent copies, is not only feasible, but can have important consequences for the interpretation of transcriptome-wide data that in this case enabled new and revised insight into what the genome actually encodes, how it is organized and how that affects gene expression.

METHODS

Sample Preparation for DRS

A. thaliana wild-type Columbia-0 (WT) seeds were sown on solid MS10 media, stratified for 2 days at 4°C and grown in a controlled environment room at a constant 24°C under 16 h light/ 8 h dark conditions. Seedlings were harvested 14 days after transfer to 24°C. Total RNA was purified using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). No subsequent poly(A) of the RNA was performed and further procedures in preparation for sequencing were done as described previously42.

Filtering Procedures for DRS Datasets

Unique DRS hits to the TAIR10 A. thaliana genome were identified using the open source Helisphere software (version 1.1.498.63) available at http://open.helicosbio.com. This software is optimized to deal better with DRS reads owing to an error model that is more appropriate to the Helicos technology. Each DRS sequence is read twice (once in each direction) by the sequencer and the consensus is aligned against the reference genome. This additional information (along with allowing for gaps in the reads and/or reference) enables the Helisphere aligner to find reliable matches for a greater number of DRS reads than other currently available programs. The indexDPGenomic aligner was given the following parameters: seed_size=18, num_errors=1, weight=16, min_norm_score=4, strands=both, read_step=4, best_only=1, max_hit_duplication=25, percent_error=0.2. filterAlign program was given the following parameters: min_score=4, min_best_score=4.0, local_ambig=rand, global_ambig=none, best_only=1. All reads aligning with >4 indels were removed (5% of the original data set), as were reads having low complexity (dustmaster from the Blast+ package 2.2.22 with default parameters except for dust level score set to 15.0). This step removed a further 15.7% of reads. Some sites were found to have sub-optimal local alignments of multiple reads, therefore a heuristic iterative algorithm was developed and applied to such regions. We obtained 23,721,197 raw sequencing reads of which 10,387,610 reads aligned to the A. thaliana genome and 10,005,529 aligned uniquely. After this filtering process, 7,881,412 reads were analyzed further. Details of read properties are given in Supplementary Table 11. All images of read alignments were made with the Integrated Genome Browser43.

Computational Analysis of Potential Non-Templated Base Addition

All TAIR10 annotated 3′UTRs (26,890) were collated and a non-overlapping set (22,724) was produced by enlarging same-strand overlapping UTRs to their maximal length. For each of these regions, 3′ ends of all DRS reads that mapped within UTR regions were analyzed. Starting from the 3′ end of each read, each base in turn was determined as being either identical to the genomic reference sequence or different (i.e. non-template). Insertions were also considered non-template positions. Once identity to the reference base was found, analysis for that read was stopped and the non-template base(s) reported. As a comparison, the same analysis was performed for the 5′ end and the 11th base from the 3′ end of each read. The 5′ and 3′ ends of reads are considered in the context of the matching strand in the genome; thus read 5′ and 3′ ends (and read sequences) are reversed for reverse strand matches.

Supplementary Table 1 details the non-template base preferences found for the 3′ end, 5′ end and 11th base positions of reads. 273,239 reads (3.5% of total reads) mapping to 19,044 3′UTR regions were found to contain apparent non-template bases at the 3′ end compared to 698,296 (8.9%) and 338,249 (4.3%) reads for the 11th base position and 5′ end, respectively. Single base changes dominate, accounting for >90% of all the non-template bases at each position within the reads. Adenine cannot be seen as a 3′ end non-template base as it makes up the poly(A) tail and therefore is not sequenced.

Data Smoothing

We replaced the real signal distribution in a given region with an approximate function. We convoluted expression at each site with coordinate p0 if the site had >1.5 raw reads in the region with the Gaussian function G(N,p0,α)=N·exp(-(p-p0)2/2·α2), where N is a normalization factor, ρ is a smoothing factor, and p can change within an interval [p0-pf, p0+ pf]. The normalization factor N was defined to have the same summed expression within the interval as the initial expression at the site. The smoothing factor ρ=2 nts (the technical uncertainty of DRS). The interval width pf was defined from the condition that expression after smoothing at the position p0-pf (p0+ pf) is 1.5 raw reads (in most cases pf is less than this due to rounding). The smoothing algorithm did not change the total number of reads in an experiment, but altered their distribution as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1a. All further analyses utilized the smoothed DRS reads.

Peak-Finding Algorithm

Sites of smoothed DRS read expression were combined into probable cleavage site (CS) peaks within a gene. Peaks were identified by iterating over the most expressed positions, pn, in a gene and combining all immediately adjacent expressed positions into a single peak corresponding to the same total expression until all reads in a gene were included within CS peaks. More specifically, adjacent positions at pn+i or pn-i, were combined until a position with no expression or a position’s expression was higher than the position next nearest to the central peak, pn+i-1 (or pn-i+1) was encountered.

This algorithm found 222,270 CS peaks in 3′UTRs of all coding genes in our smoothed data set. However, a significant proportion of the CS peaks were supported by only a few raw reads. Hence, we focused our analysis on CS peaks with >9 raw reads. 49,916 peaks were found (93.3% of all reads aligning to 3′UTRs).

The CS peaks for each gene were enumerated as 1st, 2nd, …, Nth peaks in order of read counts per peak, highest first. 10,722 coding genes have >1 CS peak. 58.2% of sequenced RNAs, which are aligned in 3′UTRs, were cleaved at the positions of the 1st peaks.

Re-Annotation of Coding Genes

The ends of 3′UTRs were extended under two conditions: 1) if a smoothed peak extended beyond the annotated end by more than one base, or 2) if up to a maximum of 300nt from the annotated end of a peak with >5 raw reads was found; the most downstream base covered by that peak was defined as the new end. These conditions refined the annotation of 10,215 genes and constructed novel 3′UTRs for 165 genes. 54.3% of formerly intergenic reads were re-annotated as within coding genes.

Motif Analysis

Histograms in Fig. 6a and b were built by counting CS with a hexamer at a given distance from CS. We applied a background correction to the counts. In particular, each CS was assigned a background weight, which took into account the probability of finding a given hexamer taking into account the AUCG composition near the CS. The probability was calculated as phex=f(A)n(A)·f(U)n(U)·f(G)n(G)·f(C)n(C), where f(A,U,C,G) are the frequencies of A,U,C,G in a neighbor region and n(A,U,C,G) are the numbers of A,U,C,G in the hexamer. The nucleotide frequencies were estimated within the neighbor region length of 40nts around the hexamer as f(A/U/C/G)=N(A/U/C/G)/40, where N(A/U/C/G) is the number of corresponding nucleotides in the region. The background weight was calculated as the ratio of the probability of having a random hexamer, i.e. (1/4)6=1/4096 of the hexamer probability. Thus, the background weight was region-dependent and changed from one CS to another.

Prediction of snoRNA Genes

Novel snoRNA candidates were identified with the snoSeeker-1.144 snoRNA predictor. Box C/D and H/ACA snoRNAs are identified with two sub-programs CDseeker and ACAseeker, respectively. We applied Ccutoff,min.=19.0 for CDseeker and Ccutoff,min.=20.0 for ACAseeker. All other parameters were set to default values. Input sequences to the snoSeeker algorithms were prepared from 601nt sequences centered on sites of DRS expression (as the longest snoRNA identified was 300nt long and we wished to search both up- and down-stream). A total of 31,842 input sequences were prepared. Then we required the presence of at least 5 DRS reads (for C/D snoRNAs) and 2 reads (for H/ACA snoRNAs) within a quarter of the length of the snoRNA candidate nearest to its 3′ end or 20 nts downstream of the 3′ end. Known snoRNAs were collated from the Plant snoRNAs Database (http://bioinf.scri.ac.uk/cgi-bin/plant_snorna/home) and literature45-47.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis of snoRNAs

RNA was isolated with TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). 10μg of total RNA was analyzed by electrophoresis on 8% acrylamide/8M urea gels. Electrotransfer onto nylon membrane (Hybond-N+) was followed by 2 min UV cross-linking at 200mJ/cm2. Membranes were probed with 10 pmol of DNA oligonucleotide probe end-labeled with [γ-32P] ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Pre-hybridization of the membranes was carried out in 50% formamide, 0.5% SDS, 5×SSPE, 5×Denhardt’s solution and 20μg/ml denatured salmon sperm DNA. Hybridizations were performed in the same solution at 37°C. After hybridization, the membranes were washed in 2×SSC, 0.1% SDS at 37°C 3 times for 5 min.

Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (3′RACE)

3′RACE was performed using the FirstChoice® RLM-RACE Kit Protocol (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction was started with 250ng of poly(A)+ RNA. Multiple PCR products were purified, cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega) and sequenced.

Primers Used in This Study

A list of primers used is given in Supplementary Table 12.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Tom Walsh for computing support, Liz Bayne and Rebecca Lyons for comments on the manuscript, Trivalent Editing and Philip Smith for proof-reading and the BBSRC (BB/H002286/1) (A.S., C.D., C.C., G.J.B., G.G.S.) and Scottish Government (C.H., G.G.S.) for funding.

Footnotes

Accession numbers. Sequencing datasets described in this study have been deposited at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA), accession no: ERP001018.

Author Contributions G.G.S. and G.J.B. conceived and supervised the research. C.H. generated RNA samples. F.O. performed DRS. A.S. and C.C. analyzed the DRS data. C.D. and V.Z. did the molecular analyses of RNA. G.G.S. wrote the paper and all authors read and commented on it.

References

- 1.Di Giammartino DC, Nishida K, Manley JL. Mechanisms and consequences of alternative polyadenylation. Mol. Cell. 2011;43:853–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proudfoot NJ. Ending the message: poly(A) signals then and now. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1770–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.17268411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornyik C, Terzi LC, Simpson GG. The spen family protein FPA controls alternative cleavage and polyadenylation of RNA. Dev. Cell. 2010;18:203–13. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greger IH, Proudfoot NJ. Poly(A) signals control both transcriptional termination and initiation between the tandem GAL10 and GAL7 genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1998;17:4771–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gullerova M, Moazed D, Proudfoot NJ. Autoregulation of convergent RNAi genes in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 2011;25:556–68. doi: 10.1101/gad.618611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuehner JN, Pearson EL, Moore C. Unravelling the means to an end: RNA polymerase II transcription termination. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:283–94. doi: 10.1038/nrm3098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyers BC, et al. Analysis of the transcriptional complexity of Arabidopsis thaliana by massively parallel signature sequencing. Nat. Biotech. 2004;22:1006–11. doi: 10.1038/nbt992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamada K, et al. Empirical analysis of transcriptional activity in the Arabidopsis genome. Science. 2003;302:842–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1088305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stolc V, et al. Identification of transcribed sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana by using high-resolution genome tiling arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4453–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408203102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu X, et al. Genome-wide landscape of polyadenylation in Arabidopsis provides evidence for extensive alternative polyadenylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:12533–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019732108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilboa E, Mitra SW, Goff S, Baltimore D. A detailed model of reverse transcription and tests of crucial aspects. Cell. 1979;18:93–100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90357-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegelman S, et al. DNA-directed DNA polymerase activity in oncogenic RNA viruses. Nature. 1970;227:1029–31. doi: 10.1038/2271029a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nam DK, et al. Oligo(dT) primer generates a high frequency of truncated cDNAs through internal poly(A) priming during reverse transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:6152–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092140899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houseley J, Tollervey D. Apparent non-canonical trans-splicing is generated by reverse transcriptase in vitro. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perocchi F, Xu Z, Clauder-Munster S, Steinmetz LM. Antisense artifacts in transcriptome microarray experiments are resolved by actinomycin D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jan CH, Friedman RC, Ruby JG, Bartel DP. Formation, regulation and evolution of Caenorhabditis elegans 3′UTRs. Nature. 2011;469:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature09616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin JZ, et al. Comprehensive comparative analysis of strand-specific RNA sequencing methods. Nature Methods. 2010;7:709–15. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozsolak F, et al. Comprehensive polyadenylation site maps in yeast and human reveal pervasive alternative polyadenylation. Cell. 2010;143:1018–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin Y, Bian T. Nontemplated nucleotide addition prior to polyadenylation: a comparison of Arabidopsis cDNA and genomic sequences. RNA. 2004;10:1695–7. doi: 10.1261/rna.7610404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loke JC, et al. Compilation of mRNA polyadenylation signals in Arabidopsis revealed a new signal element and potential secondary structures. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1457–68. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangone M, et al. The landscape of C. elegans 3′UTRs. Science. 2010;329:432–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1191244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yepiskoposyan H, Aeschimann F, Nilsson D, Okoniewski M, Muhlemann O. Autoregulation of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway in human cells. RNA. 2011;17:2108–18. doi: 10.1261/rna.030247.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houseley J, Tollervey D. The many pathways of RNA degradation. Cell. 2009;136:763–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chekanova JA, et al. Genome-wide high-resolution mapping of exosome substrates reveals hidden features in the Arabidopsis transcriptome. Cell. 2007;131:1340–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown JW, Echeverria M, Qu LH. Plant snoRNAs: functional evolution and new modes of gene expression. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:42–9. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu JQ, et al. Systematic analysis of transcribed loci in ENCODE regions using RACE sequencing reveals extensive transcription in the human genome. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Bakel H, Nislow C, Blencowe BJ, Hughes TR. Most “dark matter” transcripts are associated with known genes. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamura K, Balla S, Martin R, Liu N, Lai EC. Two distinct mechanisms generate endogenous siRNAs from bidirectional transcription in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:581–90. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borsani O, Zhu J, Verslues PE, Sunkar R, Zhu JK. Endogenous siRNAs derived from a pair of natural cis-antisense transcripts regulate salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2005;123:1279–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katiyar-Agarwal S, et al. A pathogen-inducible endogenous siRNA in plant immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18002–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608258103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufmann I, Martin G, Friedlein A, Langen H, Keller W. Human Fip1 is a subunit of CPSF that binds to U-rich RNA elements and stimulates poly(A) polymerase. EMBO J. 2004;23:616–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothnie HM, Reid J, Hohn T. The contribution of AAUAAA and the upstream element UUUGUA to the efficiency of mRNA 3′-end formation in plants. EMBO J. 1994;13:2200–10. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanfacon H, Brodmann P, Hohn T. A dissection of the cauliflower mosaic virus polyadenylation signal. Genes Dev. 1991;5:141–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayr C, Bartel DP. Widespread shortening of 3′UTRs by alternative cleavage and polyadenylation activates oncogenes in cancer cells. Cell. 2009;138:673–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:99–110. doi: 10.1038/nrg2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prescott EM, Proudfoot NJ. Transcriptional collision between convergent genes in budding yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:8796–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132270899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henz SR, et al. Distinct expression patterns of natural antisense transcripts in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1247–55. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.100396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jen CH, Michalopoulos I, Westhead DR, Meyer P. Natural antisense transcripts with coding capacity in Arabidopsis may have a regulatory role that is not linked to double-stranded RNA degradation. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R51. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-6-r51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mapendano CK, Lykke-Andersen S, Kjems J, Bertrand E, Jensen TH. Crosstalk between mRNA 3′ end processing and transcription initiation. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:410–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang L, et al. Synthetic spike-in standards for RNA-seq experiments. Genome Res. 2011;21:1543–51. doi: 10.1101/gr.121095.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozsolak F, et al. Direct RNA sequencing. Nature. 2009;461:814–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicol JW, Helt GA, Blanchard SG, Jr., Raja A, Loraine AE. The Integrated Genome Browser: free software for distribution and exploration of genome-scale datasets. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2730–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang JH, et al. snoSeeker: an advanced computational package for screening of guide and orphan snoRNA genes in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5112–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen HM, Wu SH. Mining small RNA sequencing data: a new approach to identify small nucleolar RNAs in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e69. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim SH, et al. Plant U13 orthologues and orphan snoRNAs identified by RNomics of RNA from Arabidopsis nucleoli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:3054–67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barbezier N, et al. Processing of a dicistronic tRNA-snoRNA precursor: combined analysis in vitro and in vivo reveals alternate pathways and coupling to assembly of snoRNP. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1598–610. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.137968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.