Abstract

Currently, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of acute stroke is recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, which must be administered within 6 hours after stroke onset. The pan-selective σ-receptor agonist N,N′-di-o-tolyl-guanidine (o-DTG) has been shown to reduce infarct volume in rats after middle cerebral artery occlusion, even when administered 24 hours after stroke. DTG derivatives were synthesized to develop novel compounds with greater potency than o-DTG. Fluorometric Ca2+ imaging was used in cultured cortical neurons to screen compounds for their capacity to reduce ischemia- and acidosis-evoked cytosolic Ca2+ overload, which has been linked to stroke-induced neurodegeneration. In both assays, migration of the methyl moiety produced no significant differences, but removal of the group increased potency of the compound for inhibiting acidosis-induced [Ca2+]i elevations. Chloro and bromo substitution of the methyl moiety in the meta and para positions increased potency by ≤160%, but fluoro substitutions had no effect. The most potent DTG derivative tested was N,N′-di-p-bromo-phenyl-guanidine (p-BrDPhG), which had an IC50 of 2.2 µM in the ischemia assay, compared with 74.7 μM for o-DTG. Microglial migration assays also showed that p-BrDPhG is more potent than o-DTG in this marker for microglial activation, which is also linked to neuronal injury after stroke. Radioligand binding studies showed that p-BrDPhG is a pan-selective σ ligand. Experiments using the σ-1 receptor-selective antagonist 1-[2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]-4-methylpiperazine dihydrochloride (BD-1063) demonstrated that p-BrDPhG blocks Ca2+ overload via σ-1 receptor activation. The study identified four compounds that may be more effective than o-DTG for the treatment of ischemic stroke at delayed time points.

Introduction

Stroke is the third leading cause of death and the major cause of long-term disability in the United States (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009). The only treatment currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for acute stroke is recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA), a thrombolytic agent used to restore blood-flow interrupted by a blood clot (Weintraub, 2006). However, response to rtPA therapy is time sensitive, and the drug must be administered within 6 hours after infarct (Weintraub, 2006). In addition to temporal limitations, the use of rtPA is precluded by various factors, such as uncontrolled hypertension or patient use of anticoagulants, both of which can increase the risk of intracranial hemorrhaging caused by rtPA (Derex and Nighoghossian, 2008). The lack in treatment options after ischemic stroke has driven the search for new stroke therapies.

Treatments that provide neuroprotection have also been explored in an effort to mitigate neuronal injury after ischemic stroke. The main area of research has been inhibition of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) and (±)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors. Although some in vitro studies were promising, the in vivo results were less assuring. For example, Selfotel, a synthetic NMDA antagonist, showed significant improvements in an animal model of transient focal ischemia (Loscher et al., 1998). However, Selfotel needed to be administered 1 hour before the ischemic insult for best results and showed no benefit if treatment was started >60 minutes after stroke (Madden et al., 1993). Furthermore, clinical trials were terminated early because of adverse effects (Muir, 2006).

One of the reasons for the failure of neuroprotective drugs that target a single ion channel is that ischemic stroke is a complex syndrome. For example, after an ischemic insult, neurons switch from oxidative metabolism to anaerobic glycolysis, leading to the build-up of lactate within the cells and a reduction in tissue pH (Munoz Maniega et al., 2008). This decrease in tissue pH, along with synaptic proton release triggered in neurons by ischemia, activates the acid-sensing ion channel 1a (ASIC1a) (Xiong et al., 2004; Mari et al., 2010). These channels contribute directly and indirectly to [Ca2+]i dysregulation in neurons during ischemia (Herrera et al., 2008) and are responsible for significant NMDA channel-independent brain injury after a stroke (Xiong et al., 2004). In addition, activated microglia migrate to the site of insult and are part of the immune/inflammatory response that significantly contributes to stroke injury (Faustino et al., 2011).

Sigma-1 (σ-1) receptors have been shown to be widely expressed in mammalian brain tissue (Cobos et al., 2008) and perform a number of functions, including regulation of plasma membrane ion channels and expression of antiapoptotic transcription factors (Zhang and Cuevas, 2002 Zhang and Cuevas, 2005; Zhang et al., 2009; Meunier and Hayashi, 2010). Activation of σ receptors was shown to regulate multiple Ca2+ influx pathways known to be functionally upregulated during stroke, including ASIC1a (Katnik et al., 2006; Mari et al., 2010). In light of these findings and other reports in the literature, there has been much interest in exploring σ receptors as neuroprotective mediators during an ischemic stroke. One of the most exciting discoveries relating to σ receptors in stroke therapeutics is the potential of these receptors as viable targets for stroke therapy at delayed time points. Our group showed that activation of σ receptors using o-DTG reduced neuronal injury in an animal model of ischemic stroke even when the drug was administered 24 hours after stroke (Ajmo et al., 2006).

o-DTG is a pan-selective agonist of σ receptors, binding to both σ-1 and σ-2 receptors at nanomolar concentrations, interacting with the σ-1 receptor via an amine moiety on the guanidine core (Glennon, 2005). From this parent molecule, novel compounds were designed and synthesized with the objective of developing σ ligands that inhibit increases in [Ca2+]i with higher potency during in vitro experiments. Experiments were conducted to compare the capacity of DTG analogs to affect three important contributors to the demise of brain cells after ischemic stroke: intracellular Ca2+ dysregulation produced in neurons by (1) acidosis and (2) ischemia and (3) activation and migration of microglial cells. Although previous studies using guanidine substitutions were made in an attempt to characterize the structure-affinity relationships (Reddy et al., 1994; Schetz et al., 2007), our focus was to identify the effects that steric hindrance, electrostatic interactions, or increased lipid permeability had on the structure-activity relationship in mitigating increases in [Ca2+]i. p-BrDPhG showed the greatest block in inhibiting increase in [Ca2+]i evoked via ischemia or acidosis and in mitigating activation and migration of microglial cells.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Cortical Neurons.

All experiments were performed on cultured cortical neurons from mixed sex embryonic day 18 (E18) Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN). Methods used here were identical to those previously reported for the isolation and culturing of these cells (Katnik et al., 2006). Cortical neurons were used for 10–21 days in culture, which permits synaptic contact formation and yields the most robust responses to ischemia and acidosis. Animals were cared for in accordance with the regulations and guidelines set forth by the University of South Florida’s College of Medicine Institution on Animal Care and Use Committee.

Calcium Imaging.

Intracellular Ca2+ concentration was measured in isolated cortical neurons with use of ratiometric fluorometry as previously described (Katnik et al., 2006). Cells plated on poly-l-lysine–coated coverslips were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour in B27-supplemented neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) containing 3 µg/ml of the acetoxymethylester form of fura-2 (fura-2 AM) in 0.3% DMSO. Before beginning the experiments, the coverslips were rinsed with physiologic saline solution (PSS). For experiments in which cells were exposed to in vitro ischemia, the control PSS (PSS-1) consisted of 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 7.8 mM glucose, 2.5 mM CaCl2, and 1.2 mM MgCl2 (pH to 7.2 with NaOH). The control PSS (PSS-2) for acidosis experiments contained 140 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES, 20 mM glucose, 1.3 mM CaCl2, and 1.0 mM MgCl2 (pH to 7.4 with NaOH).

PSS was used as the control solution in all experiments. Solutions were delivered onto the cells via a rapid application system identical to that described previously (Cuevas and Berg, 1998). In vitro ischemia was achieved using glucose-free PSS-1 containing 4 mM sodium azide (NaN3) (Katnik et al., 2006), and acidosis was evoked via application of PSS-2 with a pH of 6.0 (Herrera et al., 2008). Cells were only exposed to three or fewer episodes of ischemia or acidosis separated by 10 minutes wash to prevent rundown of cellular responses. For both ischemia and acidosis experiments, control recordings were made before application of σ ligands. In experiments using the σ-1 inhibitor, BD-1063, a second control recording was made in the presence of the inhibitor before application of p-BrDPhG. All test compounds were applied in PSS for 10 minutes before ischemia or acidosis onset and throughout the ischemic or acidic insult.

In Vitro Competition Binding Assays.

Rat liver P2 membrane (∼350 µg protein) was used for all σ binding assays. Membrane homogenates were incubated for 120 minutes in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, with radioligand and various concentrations of test ligand in a total volume of 500 µl, at 25⁰C, in 96-well Unifilter GF/B filter plates (Perkin Elmer 50-905-1601; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA). σ-1 Receptors were labeled with 5 nM [3H](+)-pentazocine, and σ-2 receptors were labeled with 3 nM [3H]o-DTG in the presence of 300 nM (+)-pentazocine to block σ-1 receptors. Ten concentrations of each test ligand (0.001–10,000 nM) were run in triplicate. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 50 µM haloperidol, with filters presoaked in polyethyleneimine for 45 minutes. After incubation and subsequent equilibrium, the samples were harvested and washed three times, and the bound radioactivity was counted. Data from the competition binding studies were analyzed using Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) and nonlinear regression to determine the concentration of test ligand that inhibits 50% of the specific binding of the radioligand (IC50 value). Ki values were calculated using the Cheng-Prusoff equation.

Microglial Migration.

The migration assays were performed using a 48-well microchemotaxis chamber (Neuro Probe, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) as described previously (Cuevas et al., 2011b). The bottom wells of the chamber were filled with DMEM containing the chemoattractant, ATP (100 µM), and 0.1% DMSO. In the upper chamber, 1 × 106 freshly isolated microglia were applied in DMEM. The test compounds, p-BrDPhG (30 μM) and o-DTG (30 μM), were applied both with the ATP and the microglia in the appropriate wells. These chambers were separated by a polycarbonate membrane containing 8-μm pores at a density of 1 × 103 pores/mm2. Each well has an exposed filter area of 8 mm2. Before experiments, the membrane was coated with fibronectin at 10 μg/ml in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature. The microglia were permitted to migrate for 2 hours in a CO2 incubator (5% CO2) at 37°C. The membrane was then removed, and nonmigrating microglia adhering to the top of the membrane were scraped off. The membrane was then incubated in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature, washed two times in ice-cold PBS, and washed once in distilled water. The membrane was then cut to separate the wells and placed on microscope slides, bottom of the membrane facing up. After the membrane dried, Vectashield Hardset mounting media containing 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was applied to the membrane, and a coverslip was affixed to the slide. Cells were illuminated at 359 nm and visualized at 461 nm with use of a Zeiss Axioskop 2 outfitted with a 20× objective. DAPI-positive cells were identified and counted using ImageJ in four random fields per well, and the average for the fields used as the value for the well. For each experiment, a minimum of three wells were used, and the results of at least three experiments were averaged.

Drugs and Chemicals.

The following drugs were used in this investigation: o-DTG and BD-1063 (Tocris Biosciences, Ellisville, MO), adenosine 5′-triphosphate disodium salt hydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (Invitrogen). The DTG analogs (Fig. 1) were synthesized in our laboratory via copper-catalyzed cross-coupling guanidinylation as we have previously reported (Cortes-Salva et al., 2010). The structures of the DTG analogs synthesized were subjected to verification via 13C NMR, 1H NMR, and mass spectrometry. Vehicles for drugs used were either DMSO or ethanol.

Fig. 1.

Structures of the guanidine analogs. Methyl (CH3), fluoro (F), chloro (Cl), and bromo (Br) are denoted by side group R. Absences of side group R denote the phenyl group.

Data Analysis.

Fluorescence intensities were recorded from cortical neurons in the same manner as previously described (Katnik et al., 2006; Herrera et al., 2008). Data were analyzed using Sigma Plot/Sigma Stat 11(Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). Data points represent peak means ± S.E.M. Paired and unpaired Student’s t tests were used to determine significant differences within and between groups, respectively. Results were considered to be statistically significant if P < 0.05. One- and two-way analysis of variance were used for determining significant differences for multiple group comparisons, as appropriate, followed by post hoc analysis using either a Tukey’s or Dunn’s test. Mean relative inhibitions were calculated using the following equation:

|

where C is the control response, X is the response in the presence of the test compound, and DTG represents the response in the presence of 100 µM o-DTG. The Langmuir-Hill equation was used to analyze concentration-response data.

Results

Experiments were conducted to determine the effects of o-DTG and derivatives on elevations in [Ca2+]i induced in cultured cortical neurons by ischemia. Figure 2A shows representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from four neurons during ischemia in the absence (control) and presence of the indicated drugs (all at 100 µM). Similar inhibitions were observed for all of the compounds shown. Identical experiments showed that, although removal of the methyl moiety resulted in a compound (DPhG) that was more potent than m-DTG and p-DTG, none of these compounds was statistically more potent than o-DTG in this assay (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Shifting the location of the methyl moiety produces o-DTG analogs that inhibit ischemic-induced increases in [Ca2+]i similar to the parent compound. (A) representative traces of intracellular calcium as a function of time recorded from four neurons during chemical ischemia in the absence (control) and presence of the indicated compounds. (B) mean change in peak relative inhibition of [Ca2+]i (±S.E.M.) obtained in response to ischemia for the indicated compounds all at 100 µM. Experiments preformed are identical to those in (A) (n > 47). Dagger indicates that the block by DPhG is significant greater than that produced by m-DTG and p-DTG (P < 0.05 for both).

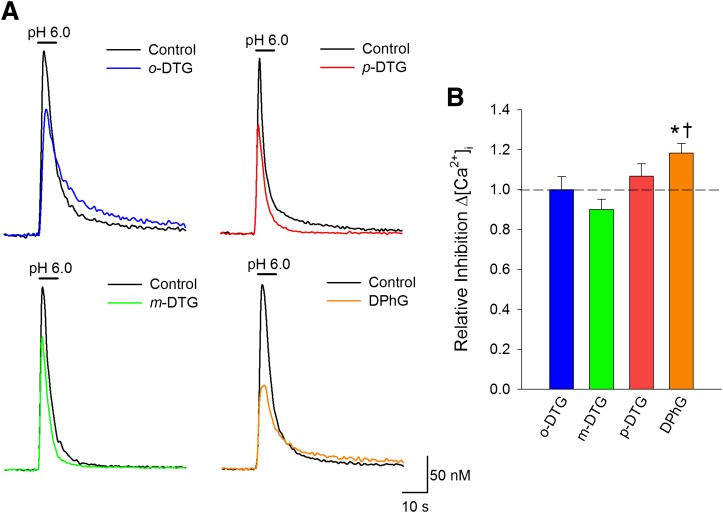

Recent studies have shown that activation of σ receptors inhibit acidosis-evoked [Ca2+]i overload (Herrera et al., 2008; Cuevas et al., 2011a). Experiments were conducted to determine whether migration or removal of the methyl moiety would alter the ability of the o-DTG derivatives to inhibit acid-evoked elevations in [Ca2+]i. Figure 3A shows representative traces of [Ca2+]i recorded from four neurons during acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of the indicated DTG analogs. Data show that all of these compounds inhibit the acid-induced elevations in [Ca2+]i. Although m- and p-DTG showed similar potency relative to o-DTG, DPhG, which lacks the methyl moiety, produced a block statistically greater than the parent compound (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B)

Fig. 3.

Removal, but not migration, of the methyl moiety increases capacity of o-DTG analogs to inhibit acidosis-evoked elevations in [Ca2+]i. (A) representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from four neurons during acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of the indicated drug. (B) bar graph of mean change in peak relative inhibition of acidosis-evoked [Ca2+]i (±S.E.M.) for the indicated compounds, all at 100 µM; experiments are identical to A. For each condition, n > 50. *Significant difference between o-DTG and DPhG (P < 0.05). †Significance between DPhG and m-DTG (P < 0.05).

Fluoro substitution of piperidine compounds has been shown to increase the lipophilicity of the molecules (de Candia et al., 2009), and several piperidine derivatives have long been used as σ receptor ligands (Nakazawa et al., 1998; Schetz et al., 2007). Further experiments were conducted to evaluate whether methyl-to-fluoro substitution of o-DTG would result in increased drug potency. Representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from three neurons are shown in Fig. 4A. Cells were exposed to ischemia in the absence (control) and presence of fluoro-substituted guanidine analogs in the ortho, meta, and para positions. Inhibitions of [Ca2+]i elevations were noted for all compounds. Identical experiments revealed that, although these compounds produced statistically significant inhibitions of ischemia evoked increases in [Ca2+]i, none of the compounds were more potent than o-DTG (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, only p-FDPhG produced inhibition that was greater than that observed for the compound with the methyl moiety at the same site (i.e., p-DTG). Figure 4C shows representative traces of [Ca2+]i recorded from three neurons evoked by acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of the specified fluoro-substituted analogs (all at 100 µM). In experiments identical to those previously shown, the fluoro-substituted guanidine analogs did not produce greater inhibitions relative to o-DTG or when compared with the compounds with a methyl moiety at the same site (i.e., m-DTG and p-DTG; Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Fluoro substitution does not affect o-DTG analog inhibition of ischemia- or acidosis-evoked increases in [Ca2+]i. (A) representative traces [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from three neurons during chemical ischemia in the absence (control) and presence of the indicated drug. (B) mean change in peak relative inhibition of [Ca2+]i (±S.E.M.) evoked by ischemia for the indicated compounds at 100 µM; measurements of experiments are identical to those in (A) (n > 58). Daggers indicate significance between o- and p-FDPhG from m-FDPhG (P < 0.05.). Pound symbol represents significant difference from relative inhibition produced by the methyl moiety in the equivalent position (P < 0.05). For comparison, block by the methyl compound is indicated by the line and arrow. (C) representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from three neurons during acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of the indicated drugs. (D) bar graph of mean change in peak relative inhibition of [Ca2+]i (±S.E.M.) obtained in response to acidosis for the indicated compounds at 100 µM (n > 67). There was no statistically significant difference between o-DTG and the analogs.

Halogen substitution is often used for enhancing permeability of a drug. It has been shown that replacing a single hydrogen residue with a chloro moiety in compounds with comparable size to DTG increased the hydrophobicity of a compound (Gerebtzoff et al., 2004). Experiments were performed to assess how methyl-to-chloro substitution of DTG in the ortho, meta, and para positions altered the ability of the compounds to affect [Ca2+]i increases evoked by ischemia and acidosis. Figures 5A shows representative traces of [Ca2+]i recorded from three neurons during episodes of ischemia in the absence (control) and presence of the chloro -substituted compounds. Inhibition of ischemia-evoked elevations in [Ca2+]i was observed for all compounds. However, only the chloro moiety substituted at either the meta or the para position increased the potency of the drug (Fig. 5B). Both m- and p-ClDPhG yielded statistically significant increases in inhibition P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively, of ischemia-induced elevations in [Ca2+]i relative to o-DTG. These compounds were also more potent than the compounds with a methyl moiety at the equivalent position (Fig. 5B). Figure 5C shows representative traces of [Ca2+]i obtained from three neurons in response to acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of the indicated drugs. The pattern of inhibition of acidosis-evoked elevations in [Ca2+]i produced by the chloro-substituted compounds was similar to that observed in the ischemia experiments. Although the block produced by o-ClDPhG did not show a significant difference when compared with o-DTG at the same concentration, both m-ClDPhG and p-ClDPhG produced a statistically significant (P < 0.001) increase in the degree of block of acidosis-elicited [Ca2+]i overload that was more than 2-fold greater than that of o-DTG, and greater than that of the equivalent methyl substitutions (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Chloro substitution at the meta and para positions increase inhibition of intracellular calcium elevations. (A) representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from three neurons during ischemia in the absence (control) and presence of the drugs shown. (B) bar graph of mean change in peak relative inhibition of [Ca2+]i (±S.E.M.) induced by ischemia for the drugs indicated at 100 µM (n > 55). (C) representative traces of [Ca2+]i from three neurons recorded as a function of time induced by acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of the drugs shown. (D) bar graph of mean change in peak relative inhibition of [Ca2+]i (± S.E.M.) evoked via acidosis for the drugs indicated at 100 µM (n > 59). For both B and D, asterisks indicate that the block by m-ClDPhG and p-ClDPhG is significantly greater than that produced by o-DTG (P < 0.001for both), daggers indicate statistical difference from o-ClDPhG (P < 0.001), and pound symbols represent significant differences from relative inhibition produced by the methyl moiety in the equivalent position (P < 0.001 for all). Lines and arrows in B and D mark the block by the methyl compound at each site and are shown for comparison.

Experiments were also performed to determine whether the substitution of a bromo moiety could likewise affect the potency of the compounds. Figure 6A shows representative traces of [Ca2+]i recorded from three neurons responding to ischemia in the absence (control) and presence of o-, m-, or p-BrDPhG, with all compounds producing some degree of block. The attenuation of ischemia-evoked elevations in [Ca2+]i resulting when the ortho substituted compound (o-BrDPhG) was applied was similar to that seen with o-DTG. However, both m-BrDPhG and p-BrDPhG blocked the [Ca2+]i overload to a greater degree, with the inhibition produced by each compound being statistically greater than o-DTG (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6B). The bromo-substituted compounds also inhibited acidosis-evoked [Ca2+]i increase. Representative traces of [Ca2+]i recorded from three neurons and demonstrating such inhibition by all of these compounds are shown in Fig. 6C. As with the ischemia assay, the m-BrDPhG and p-BrDPhG compounds were significantly more potent than o-DTG at inhibiting acidosis-induced [Ca2+]i increases (P < 0.001), but o-BrDPhG was comparable in effectiveness to o-DTG (Fig. 6D). In both the ischemia and acidosis experiments, the m- and p-BrDPhG were more potent than the equivalent methyl substitutions (Fig. 6, B and D).

Fig. 6.

Substitution of the methyl moiety with bromide at the meta and para positions enhances [Ca2+]i inhibition. (A) representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from three neurons induced via chemical ischemia in the absence (control) and presence of the indicated bromo derivatives at 100 µM. (B) mean relative inhibition of ischemia-induced change in peak [Ca2+]i (±S.E.M.) evoked by bromo derivatives at 100 µM for each drug (n > 55). (C) representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from three neurons during acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of the drugs shown. (D) bar graph of mean relative inhibition of change in peak [Ca2+]i (±S.E.M.) induced via acidosis for the drugs indicated (all at 100 µM, n > 53). For both B and D, asterisks indicate statistical differences from o-DTG (P < 0.001), daggers indicate significant difference from o-BrDPhG (P < 0.001), and pound symbols represents significant differences from the methyl moiety in that position (P < 0.001). For comparison, block by the methyl compounds in the equivalent site is indicated by the lines and arrows in B and D.

The guanidine analog that exhibited the most pronounced inhibition of [Ca2+]i overload in both assays was p-BrDPhG. Thus, further experiments were performed to precisely measure the concentration-response relationship for p-BrDPhG inhibition of [Ca2+]i overload produced by ischemia. Representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from two neurons in response to ischemia in the absence (control) and presence of 10 µM and 100 µM o-DTG and p-BrDPhG are shown in Fig. 7, A and B, respectively. Inhibitions of the [Ca2+]i elevations by both of these compounds showed a concentration dependence. Plots of the mean relative change in [Ca2+]i as a function of drug concentration for both o-DTG and p-BrDPhG are shown in Fig. 7C. The data were best fit by single-site Langmuir-Hill equations and indicate a 34-fold greater potency for p-BrDPhG in inhibiting ischemia-evoked increases in [Ca2+]i relative to o-DTG.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of ischemia-evoked increases in [Ca2+]i by p-BrDPhG is concentration dependent. Representative traces of [Ca2+]i recorded as a function of time from a single neuron during chemical ischemia in the absence (control) and presence of 10 and 100 µM o-DTG (A) or in the absence (control) and presence of 10 and 100 µM p-BrDPhG (B). (C) concentration-response relationship for mean change in peak [Ca2+]i (±S.E.M.) measured during chemical ischemia in the presence of o-DTG (open circle) and p-BrDPhG (closed circle). Drugs were normalized to their respective controls (ischemia in absence of drug for each cell). Lines were best fit to the data using single-site Langmuir-Hill equations with IC50 values and Hill coefficients of 74.7 µM and 0.58 (o-DTG) and 2.2 µM and 0.63 (p-BrDPhG), respectively. For each data point, n > 65.

Similar experiments were performed to determine the concentration-response relationship for p-BrDPhG inhibition of elevations in [Ca2+]i caused by acidosis. Figure 8A shows representative traces of [Ca2+]i recorded as a function of time from a single neuron during acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of 10 and 100 µM p-BrDPhG. Increasing the p-BrDPhG concentration resulted in further depression of acidosis-induced [Ca2+]i overload. Figure 8B shows a plot of the mean change in peak [Ca2+]i as a function of p-BrDPhG concentration obtained from multiple experiments. These results show an eight-fold greater potency of p-BrDPhG in inhibiting increases in [Ca2+]i induced via acidosis, compared with o-DTG. The efficacy of p-BrDPhG was similar to that of o-DTG in both the ischemia and the acidosis assay.

Fig. 8.

p-BrDPhG inhibits acidosis-evoked increases in [Ca2+]i in a concentration-dependent manner. (A) representative traces of [Ca2+]i recorded as a function of time from a single neuron during acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of p-BrDPhG at the indicated concentrations. (B) concentration-response relationship for mean change in peak [Ca2+]i (±S.E.M.) recorded during acidosis in the absence and presence of p-BrDPhG. Responses obtained in the presence of p-BrDPhG were normalized to control (absence of drug) for each cell (n > 72). Black line represents best fit to the data p-BrDPhG using a Langmuir-Hill equation with an IC50 value of 13.5 µM and a Hill coefficient of 1.2. Presented for comparison was the best fit to the data obtained for o-DTG inhibition of acid-evoked elevations in [Ca2+]i (red line, IC50 = 109.3 µM; Hill coefficient 0.9) (Herrera et al., 2008).

To determine whether the o-DTG derivative p-BrDPhG retains the σ receptor binding properties of the parent compound, a binding assay was performed using o-DTG for comparison. Results of the binding study are presented in Table 1 and show that p-BrDPhG binds both σ-1 and σ-2 receptors. However, the affinity for both receptors was decreased, with the affinity for σ-2 decreasing to a greater extent. The Ki for p-BrDPhG was statistically less than that for o-DTG at both σ-1 and σ-2 receptors, and the affinity of p-BrDPhG for σ-2 receptors was significantly lower than that for σ-1 receptors (for all, P < 0.001) (Table 1). Although the binding study suggests that p-BrDPhG can act via σ receptors to inhibit [Ca2+]i dysregulation, functional experiments were performed using the σ-1 receptor antagonist, BD-1063, to confirm this possibility. Figure 9, A and B, shows representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from two neurons in response to acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of 30 µM p-BrDPhG (Fig. 9A) or p-BrDPhG with 10 nM BD-1063 (Fig. 9B). p-BrDPhG produced a reduction in [Ca2+]i in the absence and presence of BD-1063. However, less block by p-BrDPhG was noted when BD-1063 was included with the guanidine analog. In identical experiments, a reduction in [Ca2+]i was noted for both p-BrDPhG and p-BrDPhG + BD-1063. However, the effects of p-BrDPhG were significantly reduced in the presence of the σ-1 antagonist, and this decrease was statistically significant (P < 0.001) (Fig. 9C). BD-1063 alone had no effect on acidosis-induced [Ca2+]i elevations (Fig. 9C).

TABLE 1.

o-DTG binds to both σ receptor subtypes with greater affinity than p-BrDPhG

Mean Ki values ± S.E.M. determined from binding assays using membrane protein extracts from rat livers. σ-1 receptors were labeled with 5 nM [3H](+)-pentazocine, and σ-2 receptors were labeled with 3 nM [3H]o-DTG in the presence of 300 nM (+)-pentazocine to block σ-1 receptors. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 50 µM haloperidol.

| Variable | Receptor* | Mean Ki | S.E.M. |

|---|---|---|---|

| nM | |||

| o-DTG | σ-1 | 91.02 | 9.7 |

| σ-2 | 60 | 8.76 | |

| p-BrDPhG | σ-1* | 296 | 46.01 |

| σ-2*# | 800.33 | 56.96 |

Significant difference between p-BrDPhG and o-DTG binding at σ-1 (P < 0.001) and σ-2 (P < 0.001) receptors.

Significant difference between p-BrDPhG affinity for σ-1 vs. σ-2 sites.

Fig. 9.

σ-1 Receptor antagonist BD-1063 attenuates p-BrDPhG inhibition of acidosis-evoked increases in [Ca2+]i. (A) representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from a single neuron during acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of 30 µM p-BrDPhG. (B) representative traces of [Ca2+]i as a function of time recorded from a single neuron during acidosis in the absence (control) and presence of 10 nM BD-1063 or 10 nM BD-1063 + 30 µM p-BrDPhG (p-BrDPhG + BD-1063). (C) bar graph of relative mean change in peak [Ca2+]i induced by acidosis. Data were normalized to values obtained for each cell in the absence of σ ligands. Asterisks denote significant differences between DMEM (n = 49) and p-BrDPhG (n = 49) (P < 0.001) and between BD-1063 (n = 53) and p-BrDPhG + BD-1063 (n = 26) (P < 0.001). Dagger indicates a statistical difference between the p-BrDPhG and p-BrDPhG + BD-1063 groups (P < 0.001). There was no statistical difference between DMEM and BD-1063 groups.

Recently, our laboratory showed that activation of σ receptors with pan-selective ligands, such as o-DTG or afobazole, modulates microglial activation and inhibits microglial cell migration in response to chemoattractants, such as ATP (Cuevas et al., 2011b). This effect on microglial cell activation has been postulated to be a mechanism by which σ receptor activation reduces ischemic stroke injury (Cuevas et al., 2011b). For this reason, experiments were performed to determine whether p-BrDPhG is also more potent than o-DTG in preventing microglial cell migration. Figure 10 shows a plot of the mean number of migrating microglial cells as a function of p-BrDPhG concentration obtained from multiple experiments. Data from 30 µM p-BrDPhG were best fit using the Langmuir-Hill equation with an IC50 value of 6.53 µM and a Hill coefficient of 0.75. Data from 30 µM o-DTG were best fit using the Langmuir-Hill equation, which showed an IC50 = 23.33 µM and Hill coefficient of 0.67. These results represent just under a 4-fold greater potency of p-BrDPhG in inhibiting microglial migration induced via 100 µM ATP, compared with o-DTG.

Fig. 10.

p-BrDPhG blocks the migration of microglia elicited by ATP. Concentration-response relationship for p-BrDPhG (closed circles) and o-DTG (open circles) inhibition of ATP-induced (100 µM) migration of microglial cells are indicated. The black line represents the best fit to the o-DTG data using a Langmuir-Hill equation with an IC50 value and Hill coefficient of 23.33 μM and 0.67, respectively. The red line represents the best fit to the p-BrDPhG data using a Langmuir-Hill equation with an IC50 value and Hill coefficient of 6.53 µM and 0.75, respectively. Points represent mean (±S.E.M.) and for all points, n > 9.

Discussion

This study demonstrates three novel findings. First, methyl-to-chloro or methyl-to-bromo substitution of DTG in the meta and para positions results in new compounds with greater potency relative to o-DTG for inhibiting [Ca2+]i overload induced by chemical ischemia or acidosis in neurons. Of the compounds tested, p-BrDPhG is the most potent in these assays. Second, our data show that p-BrDPhG binds σ receptors with a reduced affinity relative to o-DTG but that the inhibition of [Ca2+]i overload continues to be dependent on σ-1 receptor activation. The fact that p-BrDPhG has reduced σ receptor binding but increased potency in the functional assay suggests that increased lipid permeability may account for the enhanced inhibition. Finally, p-BrDPhG is also more potent than o-DTG in preventing microglial migration in response to ATP, indicating that this novel compound can effectively reduce microglial activation at lower concentrations relative to o-DTG.

Our initial experiments involved shifting and removal of the methyl moiety of DTG to ascertain effects on in vitro functional assays used to predict therapeutic potential in ischemic stroke. Our findings with the DTG analogs show that rearrangement of the methyl moiety does not produce a compound that behaves differently from the parent compound in terms of modulating [Ca2+]i increases induced via ischemia and acidosis. Removal of the group entirely (DPhG) produces a significant 18.3 ± 0.05% increase over o-DTG in inhibiting elevations in [Ca2+]i during acidosis. Similarly, DPhG show a 12.2% ± 0.04% greater inhibition than o-DTG in the ischemia assay, but this difference was not statistically significant. Previous studies have reported that the σ receptor binding affinities for o-, m-, and p-DTG are approximately 30, 50, and 530 nM, respectively; whereas the affinity of DPhG for σ receptors is ∼400 nM (Scherz et al., 1990; Reddy et al., 1994). Results from our functional studies, therefore, do not reflect the decrease in affinity observed for the p-DTG or DPhG. Calcium elevations evoked by ischemia and acidosis are in part attributable to activation of NMDA receptors (Katnik et al., 2006; Herrera et al., 2008). However, neither p-DTG nor DPhG shows increased affinity for NMDA receptors, compared with o-DTG (Scherz et al., 1990; Reddy et al., 1994), and thus, actions on that receptor cannot account for the discrepancy between σ receptor binding and functional effects. Because the earlier studies did not examine specifically σ receptor subtype binding affinity, the difference may be attributable to changes in affinity for one receptor subtype versus the other (i.e., σ-2 receptor affinity decreases significantly, but σ-1 receptor affinity remains unchanged).

Although migration and removal of the methyl moiety failed to alter functional properties of the molecule significantly, pronounced enhancement in potency were found with halide substitutions. Data presented here show that substituting a chloro for a methyl moiety in the meta and para positions of DTG produced compounds that had ∼15% higher potency relative to the parent compound (o-DTG) at 100 μM concentration in the ischemia-induced increases in [Ca2+]i assay. The enhancement in potency was even more pronounced in the acidosis-evoked [Ca2+]i dysregulation assay. In this assay, m- and p-ClDPhG (100 μM) produced blocks of > 100% greater than o-DTG. In contrast, substitution of a chloro moiety in the ortho position did not alter the functional effects of the parent compound in either the ischemia or the acidosis assay. Similar observations were made using compounds with bromo substitutions (BrDPhG) of DTG in the meta and para positions, with an ∼22% increase of inhibition during ischemia and an ∼160% increase during acidosis applications over o-DTG, respectively. The most potent compound tested was p-BrDPhG, which had an IC50, indicating 8-fold and 34-fold greater potency over that of o-DTG in the acidosis [Ca2+]i and ischemia [Ca2+]i assays, respectively.

Functional assays indicated that p-BrDPhG was significantly more potent than o-DTG, but a radioligand binding assay showed decreased affinity for both σ receptor subtypes. Our experiments showed that o-DTG binds σ-1 and σ-2 receptors with an affinity in the range of 60–90 nM, which is similar to what was previously reported in the literature (Torrence-Campbell and Bowen, 1996). In contrast, p-BrDPhG was found to bind σ-1 and σ-2 receptors with 296 ± 46 nM and 800 ± 57 nM affinities, respectively, with the σ-2 receptor affinity being significantly lower. These values are similar to a previous report that indicates that p-BrDPhG binds guinea pig brain membrane extracts with an affinity of 540 ± 25 nM (Scherz et al., 1990). That study also demonstrated that p-BrDPhG has lower binding affinity for the NMDA receptor than does the parent compound (o-DTG), and therefore, the increased functional potency cannot be explained by increased action at the NMDA receptor.

Confirmation that p-BrDPhG mitigates [Ca2+]i dysregulation via activation of σ-1 receptors was achieved via the use of the σ-1 receptor antagonist BD-1063. With use of the acidosis [Ca2+]i functional assay, BD-1063 was shown to inhibit the effects of p-BrDPhG by >50% at a concentration of 10 nM, which is consistent with p-BrDPhG acting via σ-1 receptors (Matsumoto et al., 1995; Herrera et al., 2008). To date, only activation of the σ-1 receptor has been shown to affect ischemia- and acidosis-evoked [Ca2+]i dysregulation (Katnik et al., 2006; Herrera et al., 2008), and thus, effects by the σ-2 receptor were not tested in these assays.

The current study shows that p-BrDPhG also inhibits microglial activation, and this DTG analog is 4-fold more potent than the parent compound and a second pan-selective σ agonist, afobazole (Hall et al., 2009; Cuevas et al., 2011b). Unlike ischemia- and acidosis-evoked [Ca2+]i dysregulation, which appears to be exclusively affected by σ-1 receptor activation, both σ-1 and σ-2 receptors can modulate microglial migration (Cuevas et al., 2011b). This observation may explain why p-BrDPhG, which has even lower affinity for σ-2 than σ-1, is only 4-fold more potent than o-DTG in the microglial migration assay but 8- to 34-fold more potent than the parent compound in the [Ca2+]i dysregulation experiments. The observation that p-BrDPhG is more potent than o-DTG in inhibiting microglial activation may have important therapeutic implications. Previous studies have demonstrated that activation of microglia after an ischemic insult results in the release of proinflammatory cytokines by these cells, which promotes neuronal death (Lee et al., 2001).

One mechanism that may explain the discrepancy between decreased binding affinity but increased functional potency of p-BrDPhG may be increased membrane permeability of the compound. It has been shown that chloro and bromo substitution in the para position on phenylalanine increases hydrophobicity and blood-brain barrier permeability of a drug (Gentry et al., 1999). Likewise, halogenation of small molecules has been demonstrated to increase membrane permeation (Gerebtzoff et al., 2004). It has been shown that increasing membrane permeability of a σ ligand by deprotonation increases potency of the compound, which was interpreted to suggest that the binding site for ligands, such as BD-1063, are intracellular (Vilner and Bowen, 2000). Immunolabeling studies have confirmed this hypothesis, showing that σ-1 receptors localize to the endoplasmic reticulum (Dussossoy et al., 1999; Jiang et al., 2006). Moreover, the proposed binding site for drugs, such as o-DTG, are, in part, located in the transmembrane domain of the receptor (Pal et al., 2007). Thus, by increasing membrane permeability, chloro and bromo substitution more than compensate for the decreased binding affinity.

Our data, however, also suggest that factors other than membrane permeability are likely to be involved in the effects of the halogenation and methylation. Electronegativity and conformation of the molecule are also important. For example, fluoro substitution of a distal phenyl group of a piperidine greatly increased the lipophilicity of the compound (de Candia et al., 2009). Despite the likely increased lipid permeability, our findings show that fluoro substitution does not result in increased inhibition of [Ca2+]i dysregulation evoked via ischemia or acidosis relative to o-DTG. One possibility is that, although the fluoro substitution may increase the drugs lipophilicity, the added increase in electronegativity caused by addition of a fluoro moiety may have disrupted binding of the compound to the σ receptors. Although fluorine has an electronegativity of 4.0, that of chlorine and bromine is ∼3.0. Moreover, our data suggest that location of chloro and bromo substitutions on the phenyl ring for enhanced potency were limited to either the meta or para positions. A previous report on structure-activity relationship of DTG analogs suggested that the ortho position was the most tolerant to structural modifications, including addition of electronegative moiety (Scherz et al., 1990). However, that report did not distinguish between σ-1 and σ-2 receptor binding, and thus, the effects of those modifications on the respective receptors remain to be determined.

In conclusion, these findings show that the chloro- and bromo-substituted analogs of DTG have potential applications as antistroke therapeutics, showing a greater potency for inhibiting intracellular calcium dysregulation over o-DTG. In addition, p-BrDPhG blocks microglial migration with greater potency than o-DTG, indicating that this DTG analog will both provide neuroprotection and mitigate the neuroinflammatory response known to contribute to stroke injury. By use of identical in vitro screening methods, our group recently identified another, more potent, DTG analog, N,N′-(naphthal-oyl-1)-guanidine, which produces superior in vivo outcomes in a rat ischemic stroke model (Shahaduzzaman et al., 2012). It is of significant interest to determine whether the noted enhancement in potency of p-BrDPhG in vitro also translates into superior in vivo outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Chris Katnik for comments on a draft of this article.

Abbreviations

- Afobazole

5-ethoxy-2-[2-(morpholino)-ethylthio]benzimidazole

- AM

acetoxymethyl ester

- AMPA

(±)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionicacid

- NaN3

sodium azide

- ASIC

acid-sensing ion channels

- BD-1063

1-[2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]-4-methylpiperazine dihydrochloride

- o-BrDPhG

N,N′-di-o-bromo-phenyl-guanidine

- m-BrDPhG

N,N′-di-m-bromo-phenyl-guanidine

- p-BrDPhG

N,N′-di-p-bromo-phenyl-guanidine

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular calcium concentration

- Δ[Ca2+]i

change in intracellular calcium concentration

- m-CF3DPhG

N,N′-di-m-trifluoromethyl-phenyl-guanidine

- o-ClDPhG

N,N′-di-o-chloro-phenyl-guanidine

- m-ClDPhG

N,N′-di-m-chloro-phenyl-guanidine

- p-ClDPhG

N,N′-di-p-chloro-phenyl-guanidine

- CNS

central nervous system

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DMT

N,N-dimethyltryptamine

- DPhG

N,N′-diphenyl-guanidine

- o-DTG

N,N′-di-o-tolyl-guanidine

- m-DTG

N,N′-di-m-tolyl-guanidine

- p-DTG

N,N′-di-p-tolyl-guanidine

- o-FDPhG

N,N′-di-o-fluoro-phenyl-guanidine

- m-FDPhG

N,N′-di-m-fluoro-phenyl-guanidine

- p-FDPhG

N,N′-di-p-fluoro-phenyl-guanidine

- HVACC

high-voltage–activated calcium channels

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- PSS

physiological saline solution

- Selfotel

(2S,4R)-4-(phosphonomethyl)piperidine-2-carboxylic acid

- tPA

tissue plasminogen activator

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Behensky, Seminerio, Matsumoto, Cuevas.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Cortes-Salva, Antilla.

Conducted experiments: Behensky, Seminerio.

Performed data analysis: Behensky, Seminerio.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Behensky, Seminerio, Matsumoto, Cuevas.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Florida Center of Excellence for Biomolecular Identification and Targeted Therapeutics [J.C., J.A.], the American Heart Association [Grant 11GRNT7990120 to J.C.], the State of Florida King Biomedical Research Program Team Science Program [J.C., J.A.], and the National Institutes of Health [Grants R01 DA013978 to R.M. and T32 GM081741 to M.S.].

References

- Ajmo CT, Jr, Vernon DO, Collier L, Pennypacker KR, Cuevas J. (2006) Sigma receptor activation reduces infarct size at 24 hours after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Curr Neurovasc Res 3:89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos EJ, Entrena JM, Nieto FR, Cendán CM, Del Pozo E. (2008) Pharmacology and therapeutic potential of sigma(1) receptor ligands. Curr Neuropharmacol 6:344–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Salva M, Nguyen BL, Cuevas J, Pennypacker KR, Antilla JC. (2010) Copper-catalyzed guanidinylation of aryl iodides: the formation of N,N’-disubstituted guanidines. Org Lett 12:1316–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas J, Behensky A, Deng W, Katnik C. (2011a) Afobazole modulates neuronal response to ischemia and acidosis via activation of sigma-1 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 339:152–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas J, Berg DK. (1998) Mammalian nicotinic receptors with alpha7 subunits that slowly desensitize and rapidly recover from alpha-bungarotoxin blockade. J Neurosci 18:10335–10344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas J, Rodriguez A, Behensky A, Katnik C. (2011b) Afobazole modulates microglial function via activation of both sigma-1 and sigma-2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 339:161–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Candia M, Liantonio F, Carotti A, De Cristofaro R, Altomare C. (2009) Fluorinated benzyloxyphenyl piperidine-4-carboxamides with dual function against thrombosis: inhibitors of factor Xa and platelet aggregation. J Med Chem 52:1018–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derex L, Nighoghossian N. (2008) Intracerebral haemorrhage after thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke: an update. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79:1093–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussossoy D, Carayon P, Belugou S, et al. (1999) Colocalization of sterol isomerase and sigma(1) receptor at endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope level. Eur J Biochem 263:377–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustino JV, Wang X, Johnson CE, Klibanov A, Derugin N, Wendland MF, Vexler ZS. (2011) Microglial cells contribute to endogenous brain defenses after acute neonatal focal stroke. J Neurosci 31:12992–13001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry CL, Egleton RD, Gillespie T, Abbruscato TJ, Bechowski HB, Hruby VJ, Davis TP. (1999) The effect of halogenation on blood-brain barrier permeability of a novel peptide drug. Peptides 20:1229–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerebtzoff G, Li-Blatter X, Fischer H, Frentzel A, Seelig A. (2004) Halogenation of drugs enhances membrane binding and permeation. ChemBioChem 5:676–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glennon RA. (2005) Pharmacophore identification for sigma-1 (sigma1) receptor binding: application of the “deconstruction-reconstruction-elaboration” approach. Mini Rev Med Chem 5:927–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AA, Herrera Y, Ajmo CT, Jr, Cuevas J, Pennypacker KR. (2009) Sigma receptors suppress multiple aspects of microglial activation. Glia 57:744–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera Y, Katnik C, Rodriguez JD, Hall AA, Willing A, Pennypacker KR, Cuevas J. (2008) sigma-1 receptor modulation of acid-sensing ion channel a (ASIC1a) and ASIC1a-induced Ca2+ influx in rat cortical neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 327:491–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G, Mysona B, Dun Y, Gnana-Prakasam JP, Pabla N, Li W, Dong Z, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. (2006) Expression, subcellular localization, and regulation of sigma receptor in retinal muller cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47:5576–5582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katnik C, Guerrero WR, Pennypacker KR, Herrera Y, Cuevas J. (2006) Sigma-1 receptor activation prevents intracellular calcium dysregulation in cortical neurons during in vitro ischemia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319:1355–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Dallas S, Hong M, Bendayan R. (2001) Drug transporters in the central nervous system: brain barriers and brain parenchyma considerations. Pharmacol Rev 53:569–596 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee (2009) Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 119:e21–e181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W, Wlaź P, Szabo L. (1998) Focal ischemia enhances the adverse effect potential of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists in rats. Neurosci Lett 240:33–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden KP, Clark WM, Zivin JA. (1993) Delayed therapy of experimental ischemia with competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists in rabbits. Stroke 24:1068–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari Y, Katnik C, Cuevas J. (2010) ASIC1a channels are activated by endogenous protons during ischemia and contribute to synergistic potentiation of intracellular Ca(2+) overload during ischemia and acidosis. Cell Calcium 48:70–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto RR, Bowen WD, Tom MA, Vo VN, Truong DD, De Costa BR. (1995) Characterization of two novel sigma receptor ligands: antidystonic effects in rats suggest sigma receptor antagonism. Eur J Pharmacol 280:301–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier J, Hayashi T. (2010) Sigma-1 receptors regulate Bcl-2 expression by reactive oxygen species-dependent transcriptional regulation of nuclear factor kappaB. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 332:388–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir KW. (2006) Glutamate-based therapeutic approaches: clinical trials with NMDA antagonists. Curr Opin Pharmacol 6:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Maniega S, Cvoro V, Chappell FM, Armitage PA, Marshall I, Bastin ME, Wardlaw JM. (2008) Changes in NAA and lactate following ischemic stroke: a serial MR spectroscopic imaging study. Neurology 71:1993–1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa M, Matsuno K, Mita S. (1998) Activation of sigma1 receptor subtype leads to neuroprotection in the rat primary neuronal cultures. Neurochem Int 32:337–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal A, Hajipour AR, Fontanilla D, Ramachandran S, Chu UB, Mavlyutov T, Ruoho AE. (2007) Identification of regions of the sigma-1 receptor ligand binding site using a novel photoprobe. Mol Pharmacol 72:921–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy NL, Hu LY, Cotter RE, et al. (1994) Synthesis and structure-activity studies of N,N’-diarylguanidine derivatives. N-(1-naphthyl)-N’-(3-ethylphenyl)-N’-methylguanidine: a new, selective noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist. J Med Chem 37:260–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz MW, Fialeix M, Fischer JB, Reddy NL, Server AC, Sonders MS, Tester BC, Weber E, Wong ST, Keana JF. (1990) Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of N,N’-di-o-tolylguanidine analogues, high-affinity ligands for the haloperidol-sensitive sigma receptor. J Med Chem 33:2421–2429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schetz JA, Perez E, Liu R, Chen S, Lee I, Simpkins JW. (2007) A prototypical Sigma-1 receptor antagonist protects against brain ischemia. Brain Res 1181:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahaduzzaman M, McAleer J, Grieco J, Golden J, Glover J, Hall J, Cortes-Salva M, Antilla J, Cuevas J, R. PK and Willing AE (2012) Sigma Receptor (σRs) Agonist NAPH Decreased Long-term Infarct Volume and Rescued White Matter After Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion (MCAO). Cell Transplant 21:790 [Google Scholar]

- Torrence-Campbell C, Bowen WD. (1996) Differential solubilization of rat liver sigma 1 and sigma 2 receptors: retention of sigma 2 sites in particulate fractions. Eur J Pharmacol 304:201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilner BJ, Bowen WD. (2000) Modulation of cellular calcium by sigma-2 receptors: release from intracellular stores in human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 292:900–911 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub MI. (2006) Thrombolysis (tissue plasminogen activator) in stroke: a medicolegal quagmire. Stroke 37:1917–1922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong ZG, Zhu XM, Chu XP, et al. (2004) Neuroprotection in ischemia: blocking calcium-permeable acid-sensing ion channels. Cell 118:687–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Katnik C, Cuevas J. (2009) Sigma receptor activation inhibits voltage-gated sodium channels in rat intracardiac ganglion neurons. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 2:1–11 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Cuevas J. (2002) Sigma receptors inhibit high-voltage-activated calcium channels in rat sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons. J Neurophysiol 87:2867–2879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Cuevas J. (2005) sigma Receptor activation blocks potassium channels and depresses neuroexcitability in rat intracardiac neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313:1387–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]