Abstract

The ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KATP) in mouse colonic smooth muscle cell is a complex containing a pore-forming subunit (Kir6.1) and a sulfonylurea receptor subunit (SUR2B). These channels contribute to the cellular excitability of smooth muscle cells and hence regulate the motility patterns in the colon. Whole-cell voltage-clamp techniques were used to study the alterations in KATP channels in smooth muscle cells in experimental colitis. Colonic inflammation was induced in BALB/C mice after intracolonic administration of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid. KATP currents were measured at a holding potential of −60 mV in high K+ external solution. The concentration response to levcromakalim (LEVC), a KATP channel opener, was significantly shifted to the left in the inflamed smooth-muscle cells. Both the potency and maximal currents induced by LEVC were enhanced in inflammation. The EC50 values in control were 6259 nM (n = 10) and 422 nM (n = 8) in inflamed colon, and the maximal currents were 9.9 ± 0.71 pA/pF (60 μM) in control and 39.7 ± 8.8 pA/pF (3 μM) after inflammation. As was seen with LEVC, the potency and efficacy of sodium hydrogen sulfide (NaHS) (10–1000 μM) on KATP currents were significantly greater in inflamed colon compared with controls. In control cells, pretreatment with 100 µM NaHS shifted the EC50 for LEV-induced currents from 2838 (n = 6) to 154 (n = 8) nM. Sulfhydration of sulfonylurea receptor 2B (SUR2B) was induced by NaHS and colonic inflammation. These data suggest that sulfhydration of SUR2B induces allosteric modulation of KATP currents in colonic inflammation.

Introduction

There is growing evidence that hydrogen sulfide (H2S), similar to nitric oxide and carbon monoxide, is a cell-signaling molecule with an important role in basic physiology as well as pathophysiology of organ systems. A protective role of H2S has been implicated in the gastrointestinal tract during inflammatory bowel disease. Although genetic, nutritional, and environmental factors are assumed to be involved in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease that is characterized by tissue inflammation and degeneration (Podolsky, 1999; Pezzone and Wald, 2002), altered motility is a common symptom of colonic inflammation leading to bloody diarrhea or constipation (Snape and Kao, 1988; Reddy et al., 1991; Collins, 1996; Myers et al., 1997). Significant remodeling of ion channel activity of smooth-muscle cells accounts, in part, for altered motility in colonic inflammation (Akbarali et al., 2010). Several earlier studies reported decreased activity of the voltage-gated Ca+2 channels (L-type, Cav1.2b) of colonic smooth muscle cell during inflammation due to decreased expression and/or modification of the channel protein (Liu et al., 2001; Akbarali et al., 2010; Ross et al., 2010). We have also previously shown that colonic inflammation results in enhanced activity of ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP) of the colonic smooth muscle cell in an experimental model of colitis (Jin et al., 2004). The underlying mechanism of this alteration is not clearly understood, but these channels appear to be potential targets of H2S.

KATP channel is a hetero-octamer consisting of two main subunits: a pore-forming Kir6.× (Kir6.1 and Kir6.2) and a sulfonylurea receptor (SUR1, SUR2A, and SUR2B). A functional channel is formed upon association of both these subunits (Babenko et al., 1998). The combination of the various subunits is tissue-dependent, with Kir6.1 and SUR2B being the predominant complex of the KATP channel in colonic smooth muscle (Jin et al., 2004). These channels are weakly inwardly rectifying, regulate the contractility of the smooth muscle cell, and contribute to the motility patterns in the colon (Koh et al., 1998).

Recent studies have shown that the KATP channel is one of the major targets of H2S (Mustafa et al., 2009; Zhong et al., 2010; Mustafa et al., 2011). H2S is produced by three main enzymes—cystathionine-β-synthase, cystathionine-γ-lyase, and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase—in enteric neurons, smooth muscle cells, and other cell types. It is also known to be produced by enteric bacteria. Although there still remains significant controversy as to the pro- or anti-inflammatory properties of H2S (Whiteman and Winyard, 2011), several H2S-releasing drugs have been developed, with promising results in the preclinical studies (Linden et al., 2010; Wallace et al., 2012). In an experimental model of colitis, Wallace et al. (2009) demonstrated an increased capacity of the colon tissue to synthesize H2S and provide a protective role due to modulation of the KATP channels. However, the mechanism and the interaction between H2S and the KATP channels in the setting of colonic inflammation are not known.

In the present study, we sought to determine the basis by which KATP channel is modulated by H2S in colonic smooth muscle during inflammation. Our studies show that the potency and efficacy of the KATP channel opener, levcromakalim (LEVC), and H2S are enhanced during colonic inflammation. The data also indicate that H2S allosterically modulates the KATP channel through sulfhydration of the SUR2B subunit, resulting in enhanced activation of the channel and providing a basis for altered motility in inflammatory conditions.

Materials and Methods

Trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS), glibenclamide, and trypsin (from bovine pancreas) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). LEVC was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN). H2S was purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). Collagenase was purchased from Worthington (Lakewood, NJ). Bovine serum albumin was purchased from American Bioanalytical (Natick, MA). Sodium chloride (NaCl), magnesium chloride (MgCl2), calcium chloride (CaCl2), glucose, ATP disodium salt, HEPES, EGTA, and tetraethylammonium chloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse Kir6.1 cDNA was purchased from Open Biosystems (Lafayette, CO).

Animals

Adult male BALB/C mice that weighed 25–30 g were housed in animal care quarters under a 12-hour/12-hour light/dark cycle with food and water. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use committee at Virginia Commonwealth University. All studies were performed under the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as promulgated by the US National Institutes of Health.

Methods

Induction of Inflammation.

Inflammation was induced in the colon of the BALB/C mice through intracolonic administration of TNBS (0.1 ml). TNBS solution was prepared by mixing equal proportions of 5% w/v picrylsulfonic acid with 50% ethanol. Weights of the mice were monitored on a daily basis, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) assay was performed on the colon tissue at different time points after the administration of TNBS to determine the severity of inflammation.

MPO Assay.

Colon samples were collected from control and inflamed mice. Cell lysate was prepared from these samples and centrifuged. Supernatant collected from centrifuged sample was used for the assay. Chlorination activity assay was performed to determine the MPO activity of the sample. The assay was performed as directed by the protocol provided along with the MPO assay kit.

Cell Isolation.

Smooth muscle cells were isolated from the colon of male BALB/C mice (25–30 g) as described previously (Jin et al., 2004). Mice were euthanized and the colon was isolated. The colon was then cut open across the mesenteric border and the mucosa was scrapped off to isolate the muscle layer. This whole process was carried out in a low–calcium Tyrode’s solution. The muscle layer was then cut into small pieces and transferred into Tyrode’s solution (containing 1.5 mg of collagenase, 1 mg of trypsin, and 5 mg of bovine serum albumin in 5 ml) for 10–12 minutes at 37°C. Then the tissue was subjected to gradual trituration with a flame-polished glass bore. The partially digested tissue was then transferred into the enzyme-free solution, subjected to further trituration, and monitored under a microscope to check for the dispersed cells. The dispersed cells were stored in ice and could be used for 6 hours. All the electrophysiological recordings were done at room temperature (22–25°C).

Electrical Recordings.

Standard whole-cell configuration was used for all recordings. The patch-clamp amplifier used was EPC 10 (HEKA, Bellmore, NY). The micropipettes were prepared on a Flaming-Brown horizontal puller (P-87; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and fire polished. Resistance of the pipettes used was 5–10 MΩ. In a gap-free protocol, the cell was held at a voltage of −60 mV and currents were measured continuously for 15 minutes; in the I-V protocol, the cell was held at a voltage of –60 mV and the currents were elicited by depolarization from –120 to 0 mV in 10-mV steps.

Solutions.

Solutions used for recordings in the whole-cell configuration are listed in Table 1. The low-calcium Tyrode’s solution was equilibrated with 95% O2,5% CO2. The pH of all bathing solutions was adjusted to 7.4 by using 3N KOH. The KATP currents were recorded in a high K+ (140 K+ external) external bath solution that specifically isolated and amplified the KATP currents.

TABLE 1.

Solutions used for cell isolation and electrophysiological recordings

| Low Ca+2 Tyrode | Whole-Cell Recording |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal | 5 K+ External | 140 K+ External | |

| mM | |||

| 137 NaCl | 100 K+ aspartate | 135 NaCl | 140 KCl |

| 2.7 KCl | 30 KCl | 5.4 KCl | 10 HEPES |

| 0.008 CaCl2 | 5 HEPES | 0.33 NaH2PO4 | 1 MgCl2 |

| 0.88 MgCl2 | 1 MgCl2 | 5 HEPES | 0.1 CaCl2 |

| 0.36 NaH2PO4 | 10 EGTA | 1 MgCl2 | 1 TEA |

| 12 NaHCO3 | 0.1 ATP Na2 | 2 CaCl2 | |

| 5.5 glucose | 5.5 glucose | ||

TEA, tetraethylammonium chloride.

Biotin-Switch Assay.

The assay was carried out as described previously (Mustafa et al., 2009) with modification. In brief, mouse colon tissues or cells treated with or without 1 mM NaHS were homogenized in HEN buffer (250 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH, 7.7], 1 mM EDTA, 2.5% SDS, and 0.1 mM neocuproine) supplemented with 100 μM deferoxamine. Protein samples (250 μg) were added to blocking buffer (HEN buffer adjusted to 2.5% SDS and 20 mM methylmethane thiosulfonate) at 50°C for 20 minutes with frequent vortexing. After acetone precipitation, the proteins were resuspended in HENS buffer (adjusted to 1% SDS). A total of 4 mM biotin-HPDP (N-[6-(Biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)-propionamide) in dimethyl formamide was added to the suspension. After 3-hour incubation at 37°C, biotinylated proteins were precipitated by streptavidin-agarose beads, which were then washed with HENS buffer. The biotinylated proteins were eluted by SDS-PAGE sample buffer and subjected to Western blot analysis. For quantitation of protein sulfhydration, samples were run on blots alongside total lysates (“load”). Anti–goat-SUR2B and anti–goat-Kir6.1 were used at 1:200 to approximately 1:1000 dilution (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Data Analysis.

SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA) was used for the analysis of the data and to plot the graphs. EC50 values were calculated using a four-parameter logistic nonlinear regression model in SigmaPlot. Significance levels were determined using unpaired t tests. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant finding. All data are expressed and mean ± SEM.

Results

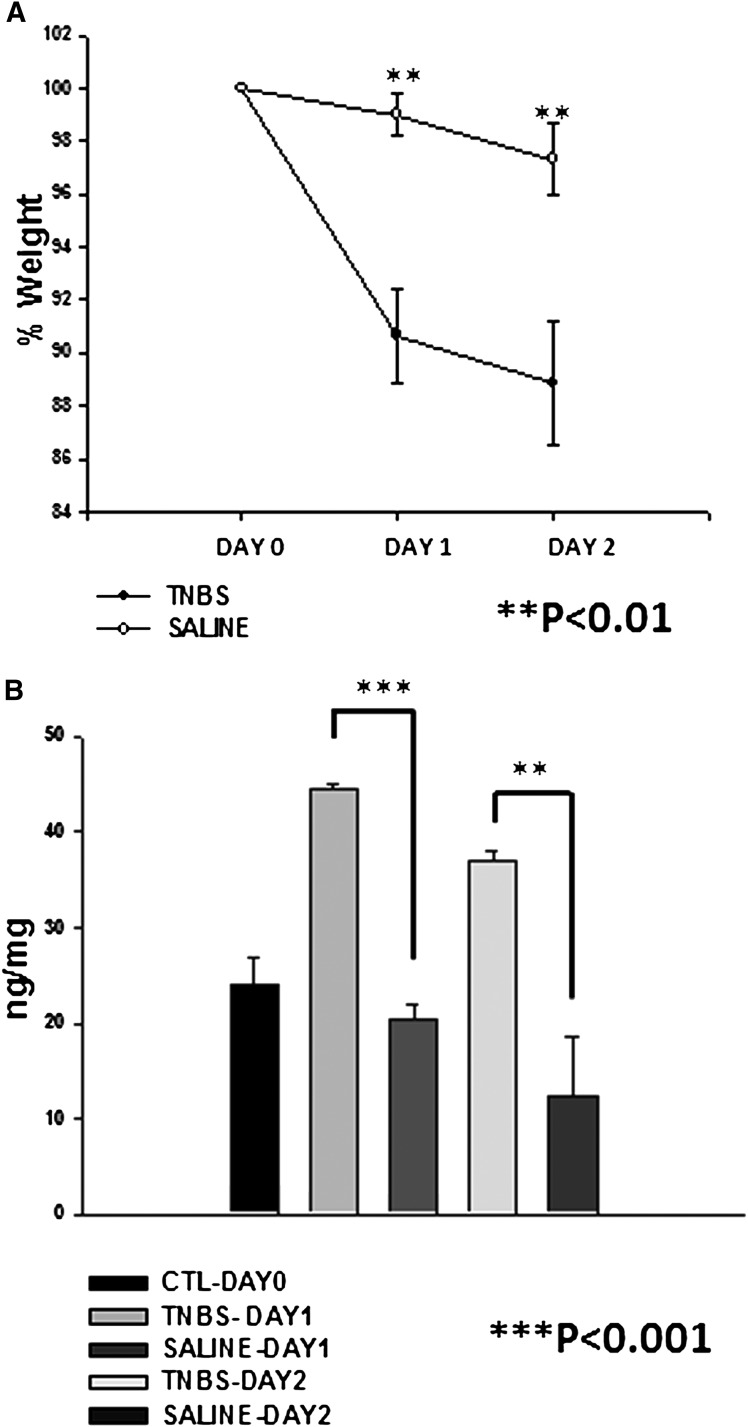

Mice treated with TNBS displayed a significant weight loss on day 1 and 2 after the treatment. MPO assay performed with the colon tissues also displayed a significant increase in MPO activity on day 1 and 2 after treatment with TNBS. This increase in MPO activity also showed significant differences compared with mice treated with control vehicle (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Disease activity index. (A) percentage decrease in the weight of animals after treatment with TNBS (n = 13) and saline (n = 5). (B) MPO activity in mice in control and after treatment with TNBS (n = 4) and saline (n = 5).

Enhancement of the KATP Channel Opener Induced Currents in Inflammation.

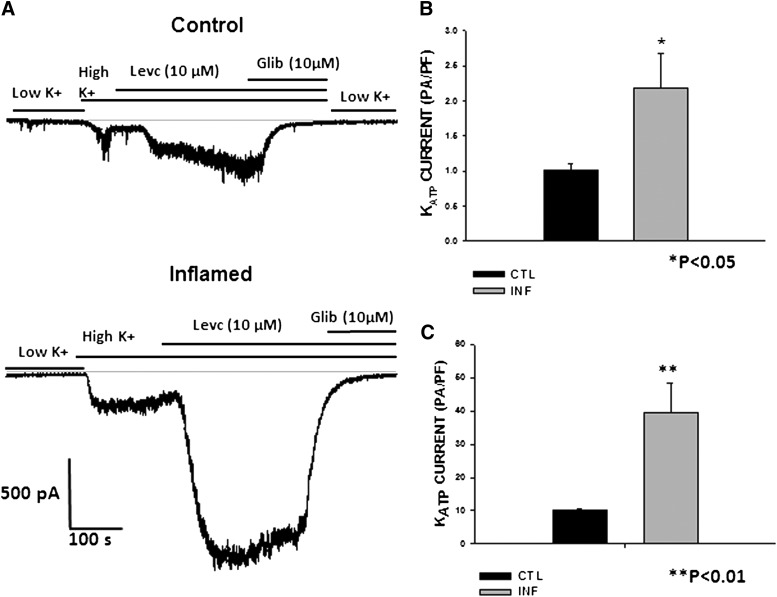

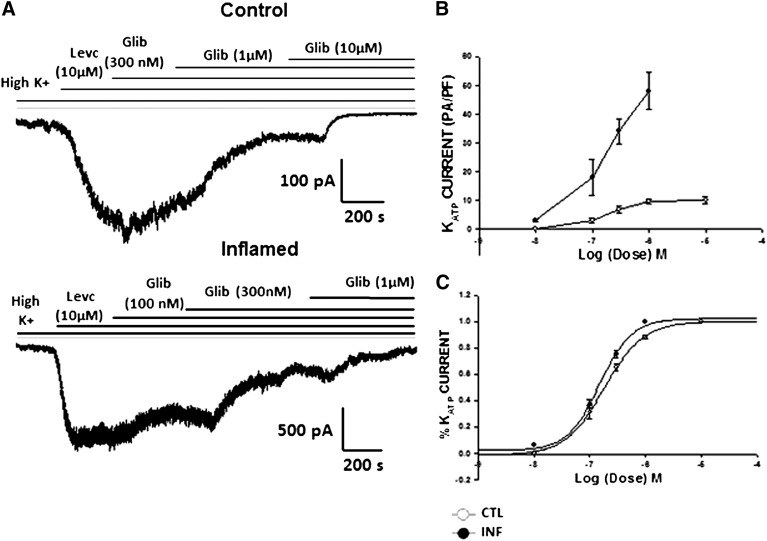

To study the alterations in KATP channel activity in inflammation, currents were recorded from freshly dispersed smooth muscle cells of distal colon using the whole cell configuration of the voltage clamp technique. To identify the KATP channel currents, cells were bathed in a high K+ (140 mM) external bath solution, held at a holding potential of −60 mV and dialyzed with low ATP (0.1 mM) in the pipette solution as previously described (Jin et al. 2004). Perfusion from a low- (5.4 mM) to high-K+ solution resulted in inward currents. The basal currents recorded in the high-K+ solution were 0.9 ± 0.12 pA/pF (n = 14) in controls and 2.17 ± 0.4 pA/pF (n = 10) in colonic smooth muscle cells from TNBS-treated mice, henceforth referred to as inflamed cells. The average capacitance was 58.93 ± 2.05 pF (n = 39) in control and 45.40 ± 2.28 pF (n = 20) in inflamed cells (P < 0.001). Although the average cell size was significantly decreased in inflamed cells, the average current amplitude normalized to cell capacitance was significantly enhanced. The high K+-induced currents were abolished by glibenclamide, suggestive of increased basal activity of KATP in inflamed cells. The KATP channel opener, LEVC, further enhanced inward currents at −60 mV. The channel opener- induced currents measured after subtraction of baseline currents in high K+ showed a remarkable increase from 9.9 ± 0.71 pA/pF in control cells to 39.7 ± 8.8 pA/pF in cells from inflamed colon, demonstrating an enhancement of almost sevenfold in inflammation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

LEVC-induced currents in control and inflamed cells. (A) raw traces showing the inward current induced by the channel opener LEVC in a whole-cell recording of gap-free protocol at −60 mV in the control and inflamed cells. (B) normalized amplitude of basal KATP currents in control and inflamed cells (control, 0.9 ± 0.12 pA/pF [n = 14]); inflamed, 5.5 ± 1.4 pA/pF [n = 12]). (C) normalized amplitude of LEVC (10 µM)-induced currents in control and inflamed cells (control, 9.9 ± 0.71 pA/pF [n = 12]; inflamed, 39.6 ± 8.8 pA/pF [n = 10]). Glib, glibenclamide. CTL, control; INF, inflamed.

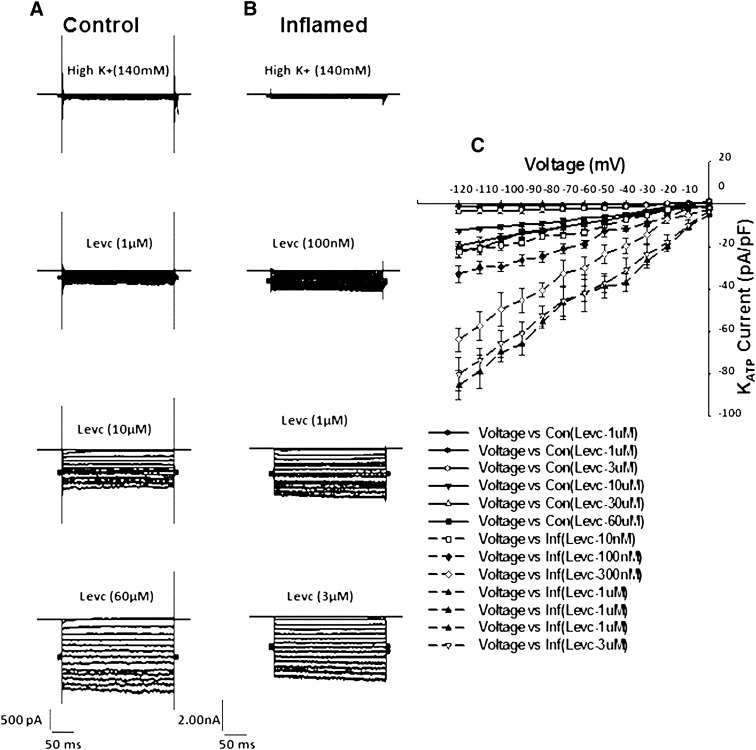

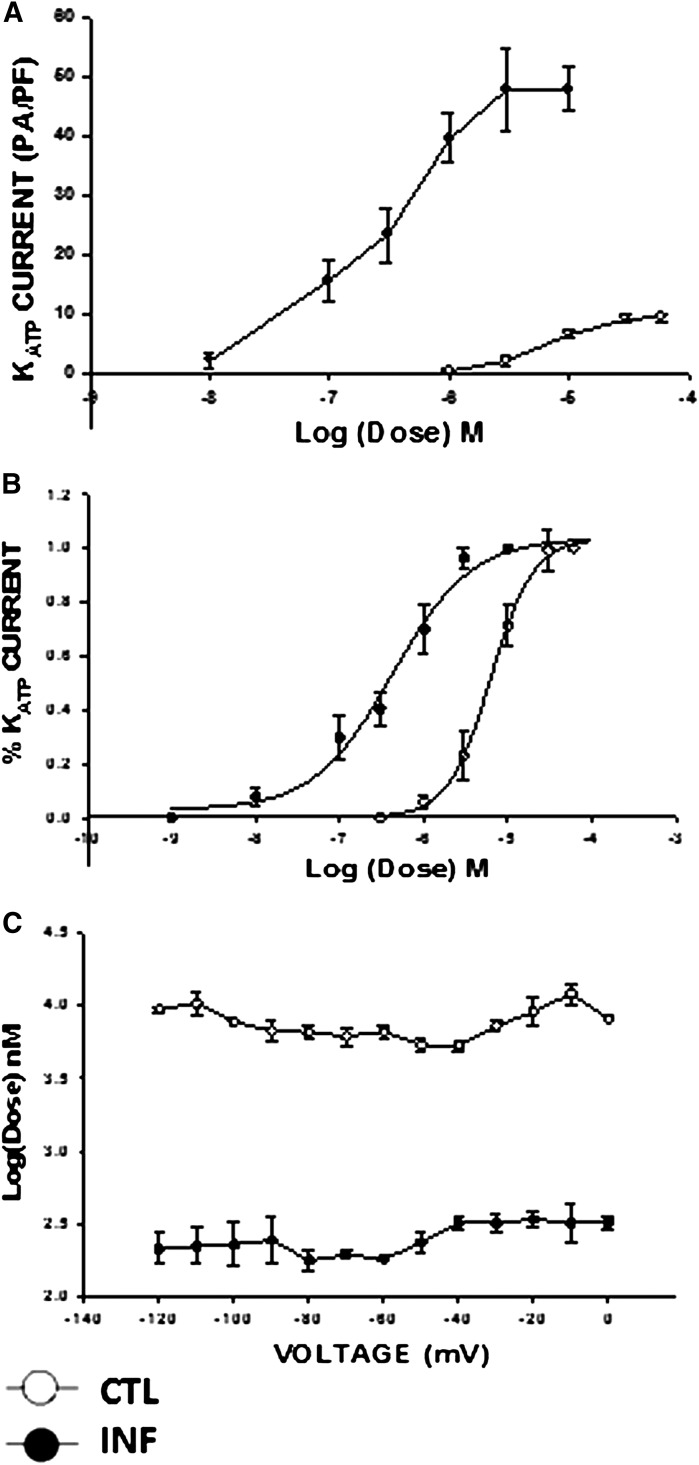

Test depolarizations from −120 to 0 mV in 10-mV increments (holding potential, −60 mV) resulted in time-independent and weakly voltage-dependent currents. Figure 3 shows current-voltage relationships for LEVC-induced currents in control and inflamed cells in the presence of various concentrations of LEVC. Compared with control cells, inflamed cells induced significantly larger currents at each potential and were more sensitive to the channel opener. A concentration-response curve for LEVC-induced currents was plotted at each voltage. Figure 4 shows the concentration response at −60 mV for control (open circles) and inflamed (closed circles). There was both a leftward shift in the concentration response and an enhancement of the maximal current in inflamed cells. The significant shift in potency was evident when current amplitudes at each concentration were plotted as a fraction of the maxima (Fig. 3B). The EC50 values calculated for LEVC shifted from 6259 nM (95% confidence limits [CL], 4909–7625 nM) (n = 10) in control cells to 422 nM (95% CL, 273–522 nM) (n = 8) in cells from the inflamed colon showing a 10-fold difference. This finding suggested that inflammation results in an increase in affinity and efficacy for the KATP channel opener. To further examine whether there was a voltage dependency to the affinity for LEVC, the EC50 values were plotted for each potential. The EC50 values were not different at any of the different potentials, with inflamed cells being more sensitive to LEVC (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Voltage and dose dependence of LEV-induced currents. Currents were recorded in a series of step voltages applied from −120 to 0 mV in 10-mV increments from a holding potential of −60 mV in high K+ solution. (A and B) current traces in high K+ and in different concentrations of LEVC in control and inflamed cells. Note the difference in scale bars. (C) current-voltage relationship with different concentrations of LEVC in control and inflamed cells. Con, control; Inf, inflamed.

Fig. 4.

Concentration-response relation of LEVC. (A) the normalized amplitude of current induced at each dose of LEVC measured at a holding voltage of −60 mV in the smooth muscle cells from control and inflamed colon. (B) the percentage of current induced at each dose of LEVC as a function of the maximum current induced at a holding voltage of −60 mV in the smooth muscle cells of the control and inflamed colon cells. The affinity and efficacy of the channel opener are enhanced in colonic inflammation. The EC50 values calculated for the drug shifted from 6259 nM (95% CL 4909–7625 nM) (n = 10) in controls to 422.1 nM (95% CL 273–522 nM) (n = 8) in cells from the inflamed colon. (C) voltage dependence of calculated EC50 values in control and inflamed cells. CTL, control; INF, inflamed.

Effect of KATP Channel Blocker in Inflammation.

We next tested whether the KATP channel blocker glibenclamide demonstrated any difference in the potency toward inhibition of LEVC-induced currents during inflammation. A cumulative concentration response for glibenclamide-induced inhibition of the KATP currents was conducted in the presence of 10 μM LEVC (Fig. 5). Although there were significantly larger LEVC-induced currents in inflamed cells, the concentration-response relationship showed no difference in the potency of glibenclamide to inhibit KATP currents in control or inflamed cells. The IC50 values were 183 nM (95% CL 154–217 nM) (n = 6) in control and144 nM (95% CL 128–162 nM) (n = 5) in the cells from inflamed colon (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of glibenclamide (Glib) on KATP channels in inflammation. (A) raw traces showing the inhibition of the LEVC-induced currents by different concentrations of glibenclamide in a whole-cell recording through the gap-free protocol at −60 mV in control and inflamed cells. (B) concentration-response curve plotted with the normalized currents inhibited by different concentrations of glibenclamide. (C) concentration-response curve plotted with the percentage of current inhibited at different concentrations of glibenclamide as a function of maximum current inhibited. IC50 values shifted from 183 nM (95% CL 154–217nM) (n = 6) in controls to 144 nM (95% CL 128–162 nM) (n = 5) in the cells from inflamed colon. CTL, control; INF, inflamed.

Effect of H2S on KATP Channels of Colonic Smooth Muscle Cell

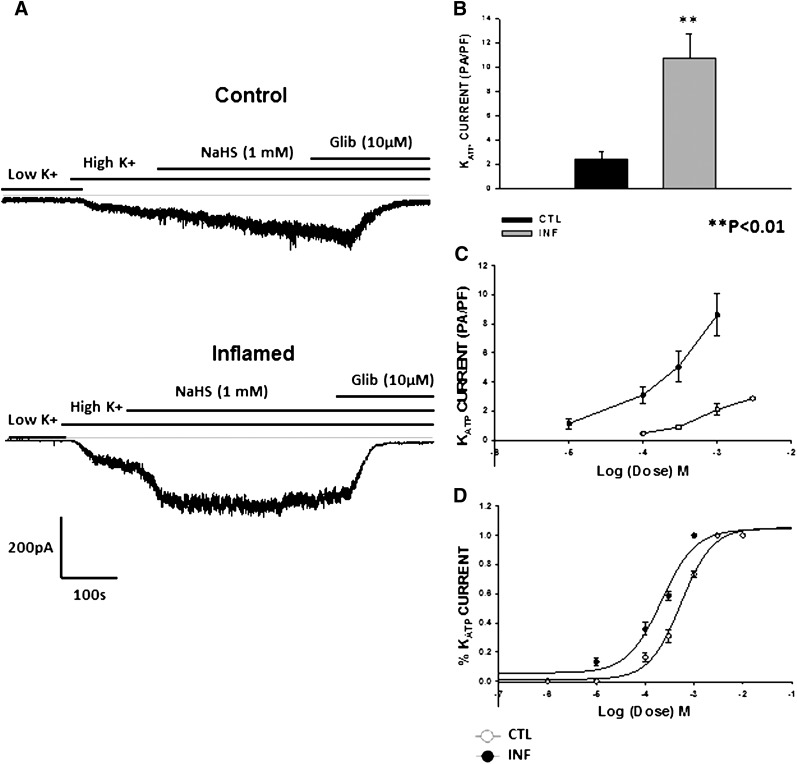

We next examined the effect of H2S, an endogenous signaling molecule whose levels have been shown to be increased in colonic inflammation (Wallace et al., 2009). Exogenous NaHS (1 mM) when added to the external bath solution induced inward currents at −60 mV in a gap-free protocol. The currents were abolished by glibenclamide (10 μM). Similar to the effects of LEVC, the inward currents activated by 1 mM NaHS were significantly larger in inflamed cells (8.6 ± 1.4 pA/pF; n = 6) than control cells (2.47 ± 0.1; n = 7)

We also tested the concentration dependence of NaHS in control and inflamed cells. There was a significant shift in the concentration-response curve to the left in inflamed cells with an increase in the maximal currents. When plotted as the fraction of maximal currents, the EC50 values shifted from 461 µM (95% CL 376–564 µM) (n = 7) in control cells to 199 µM (95% CL 140–283 µM) (n = 6) in inflamed cells (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Effect of H2S on KATP channels of colonic smooth muscle cell. (A) raw traces showing the NaHS (H2S donor)-induced currents in a whole cell recording at −60 mV voltage through a gap-free protocol in control and inflamed cells. (B) normalized amplitude of inward currents induced by NaHS in control and inflamed cells (control, 2.4 ± 0.5 pA/pF [n = 6]; inflamed, 10.7 ± 1.9 pA/pF [n = 7]) (C) concentration-response curve plotted using the amplitudes of currents induced with different concentrations of NaHS in control and inflamed cells. (D) the percentage of current induced at each dose of NaHS as a function of the maximum current induced at a holding voltage of −60 mV in the smooth muscle cells of the control and inflamed colon cells. The affinity and efficacy of the channel opener are enhanced in colonic inflammation. The EC50 values calculated for NaHS shifted from 461 µM (95% CL 376–564 µM) (n = 7) in controls to 199 µM (95% CL 140–283 µM) (n = 6) in cells from the inflamed colon. CTL, control; Glib, glibenclamide; INF, inflamed.

Effect of H2S on KATP Opener Induced Currents.

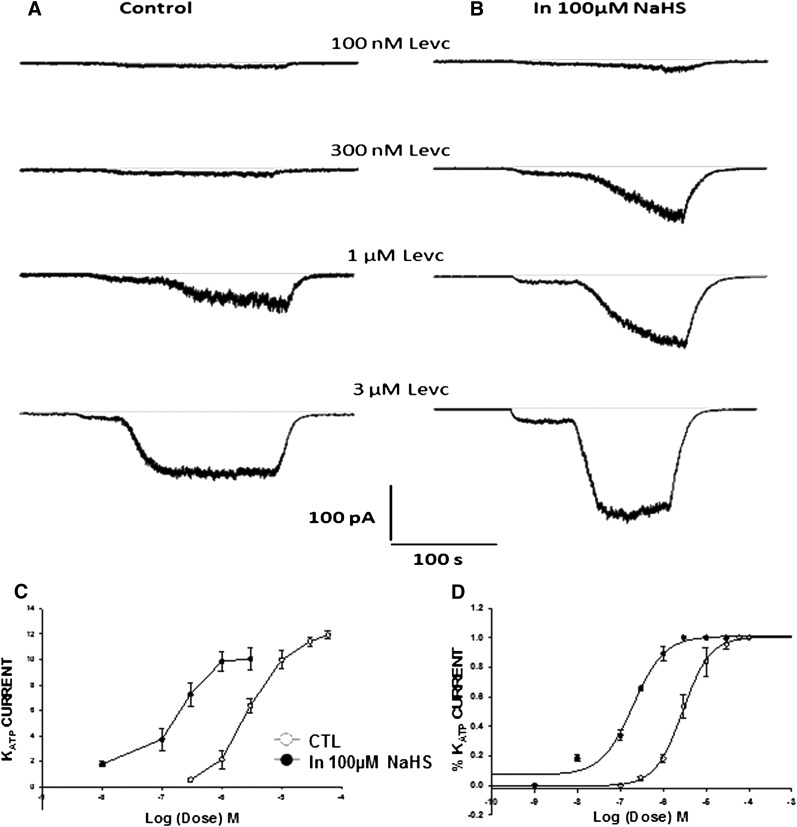

To examine whether NaHS acts as an allosteric modulator of LEVC-induced KATP currents, a low dose of H2S (100 µM) was bath applied before LEVC concentration response was conducted. In the presence of 100 μM, the currents activated were 0.47 ± 0.04 pA/pF. In the presence of this concentration of H2S, the channel opener showed an increased affinity toward the channel and induced currents at lower doses. The curve plotted shifted to the left and the EC50 values calculated shifted from 2838 nM (95% CL 954–4625 nM) (n = 6) to 154.9 nM (95% CL 94–251 nM) (n = 8) in the presence of 100 µM NaHS, demonstrating an increase in affinity of the drug similar to what was seen in the case of inflammation. At this concentration of NaHS, there was no increase in the maximal amplitude of current induced by LEVC (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effect of H2S on LEVC-induced currents. (A) current traces in the presence of different concentrations of LEVC in control. (B) current traces in the presence of different concentrations of LEVC in the presence of 100 µM NaHS. (C) the amplitude of current induced at each dose of LEVC measured at a holding voltage of −60 mV in the smooth muscle cell under control conditions and in the presence of 100 µM NaHS (n = 8). (D) the percentage of current induced at each dose of LEVC as a function of the maximum current induced at a holding voltage of −60 mV in the smooth muscle cell under control conditions and in the presence of 100 µM NaHS. In the presence of NaHS, the affinity of LEVC is enhanced. The EC50 values showed a leftward shift (control, 2838 nM [95% CL 1254–3625 nM]; inflamed, 100 µM NaHS:154.9 nM [95% CL 94–251 nM]). CTL, control; IN, inflamed.

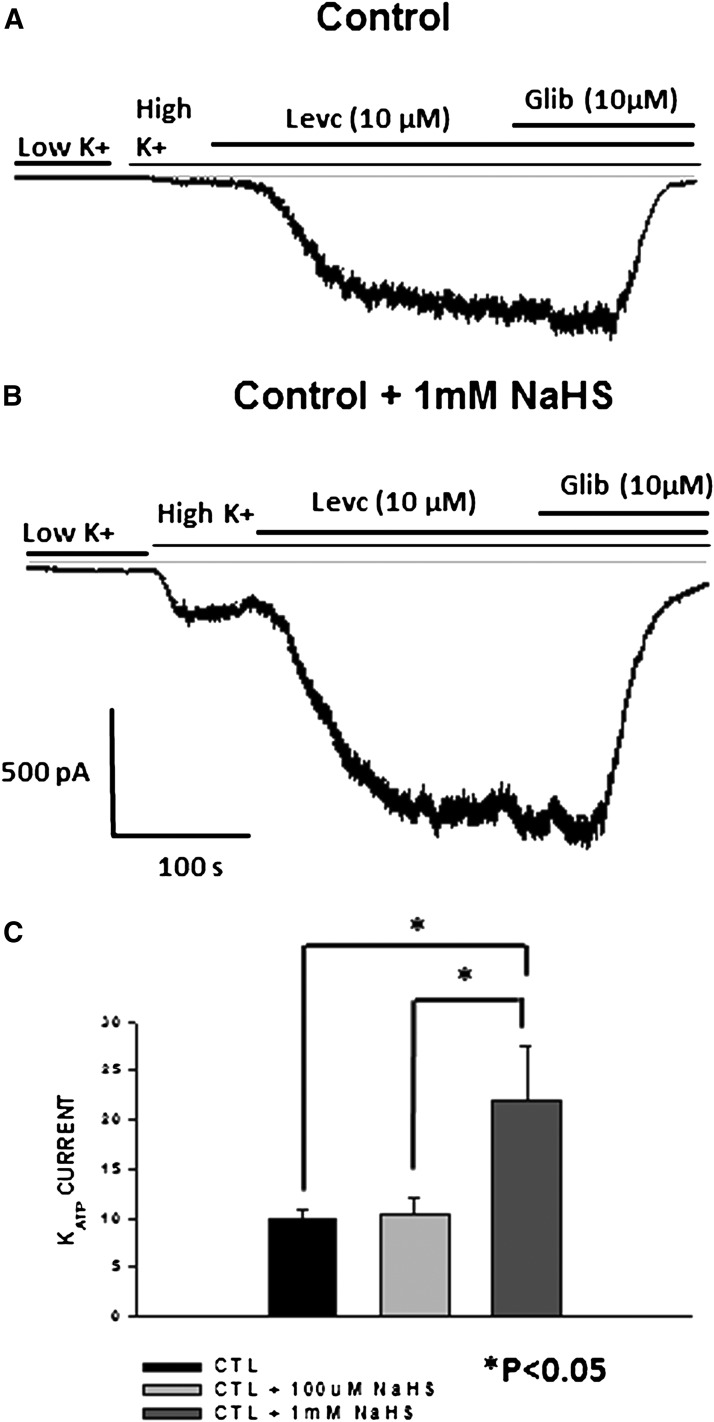

This study was repeated in the presence of a higher concentration of NaHS (1 mM) in which a maximal concentration of the channel opener (10 µM) was used to induce KATP currents. The maximal amplitude of the inward currents induced by the opener increased from 10.5 ± 1.6 pA/pF (n = 6) in the presence of 100 µM H2S to 22 ± 5.4 pA/pF (n = 4) in the presence of 1 mM of H2S, demonstrating an increase in the efficacy of the drug in the presence of higher concentration of H2S (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

(A) current trace showing the response to LEVC in controls. (B) current trace showing the response to LEVC in the presence of 1 mM NaHS. (C) amplitude of current induced by 10 µM LEVC in the control cells and in the presence of different doses of NaHS (H2S donor). Amplitude of LEVC-induced currents is enhanced in the presence of high NaHS demonstrating an increase in efficacy of LEVC (control, 9.9 ± 0.71 pA/pF [n = 12]; control plus 100 µM NaHS, 10.5 ± 1.6 pA/pF [n = 8]; control plus 1 mM NaHS, 22 ± 5.4 pA/pF [n = 5]). CTL, control; Glib, glibenclamide.

Effect of N-Ethylmaleimide on Opener and NaHS-Induced Current.

To examine the involvement of cysteine residues in the action of H2S, effect of N-ethylmaleimide (NEM, an alkylating agent of free cysteine residues) was tested on NaHS- and LEVC- induced currents. In the presence of 2 mM NEM, the responses produced by NaHS and LEVC were significantly decreased, indicating a strong involvement of cysteine residues on their action (Fig. 9). NaHS-induced currents decreased from 2.47 ± 0.56 pA/pF in control to 0.0397 ± 0.001 (n = 4) in the presence of NEM. LEVC-induced currents were reduced from 9.9 ± 0.71 in control to 0.45 ± 0.3 in the presence of NEM (n = 4).

Fig. 9.

(A) current traces showing the response to LEVC in controls and in the presence of 2 mM NEM. (B) current traces showing the response to 1 mM NaHS in controls and in the presence of 2 mM NEM. (C) bar graph showing the quantified differences in the amplitude of drug-induced currents blocked by NEM. Glib, glibenclamide.

H2S Sulfhydrates SUR2B but Not Kir6.1 Subunit of KATP Channel.

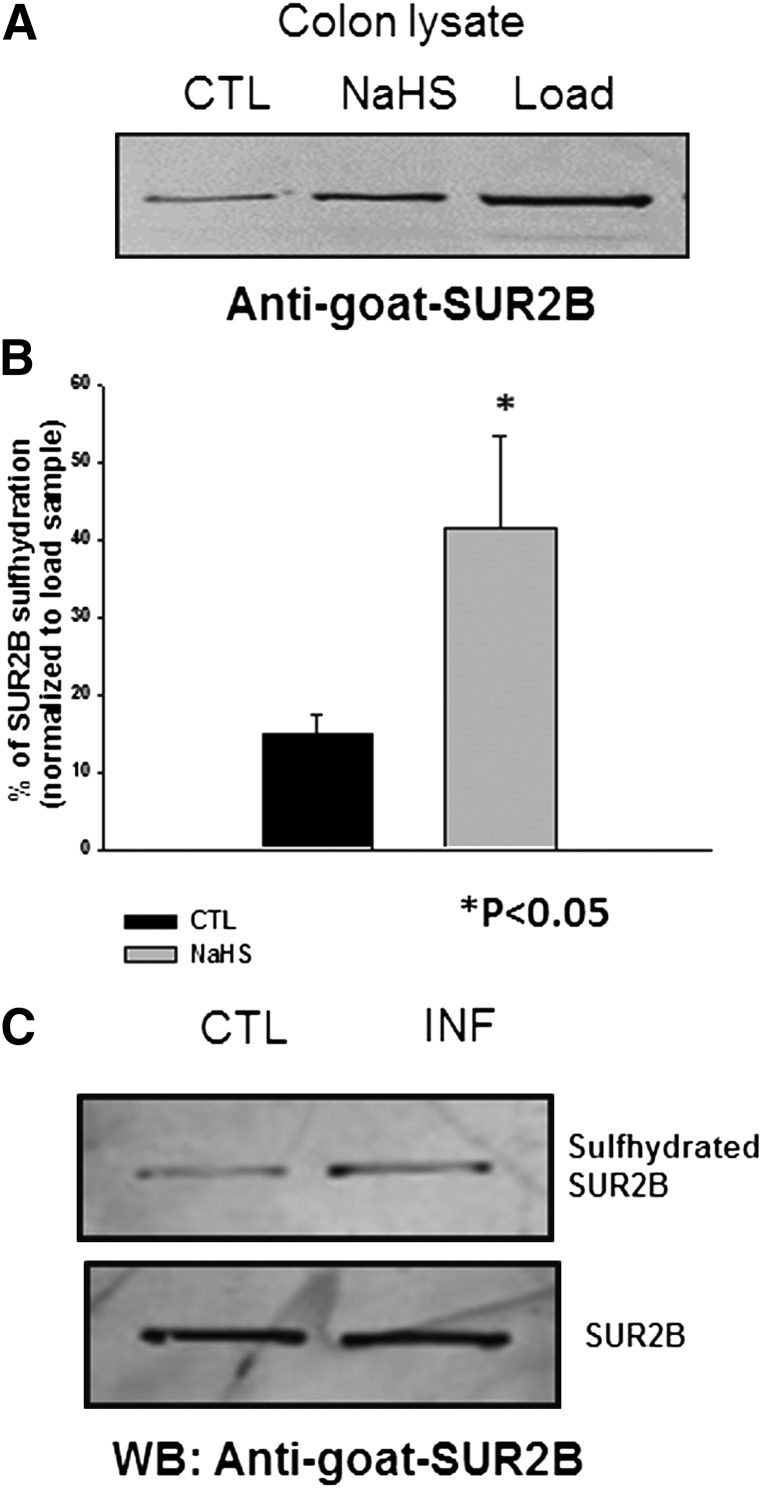

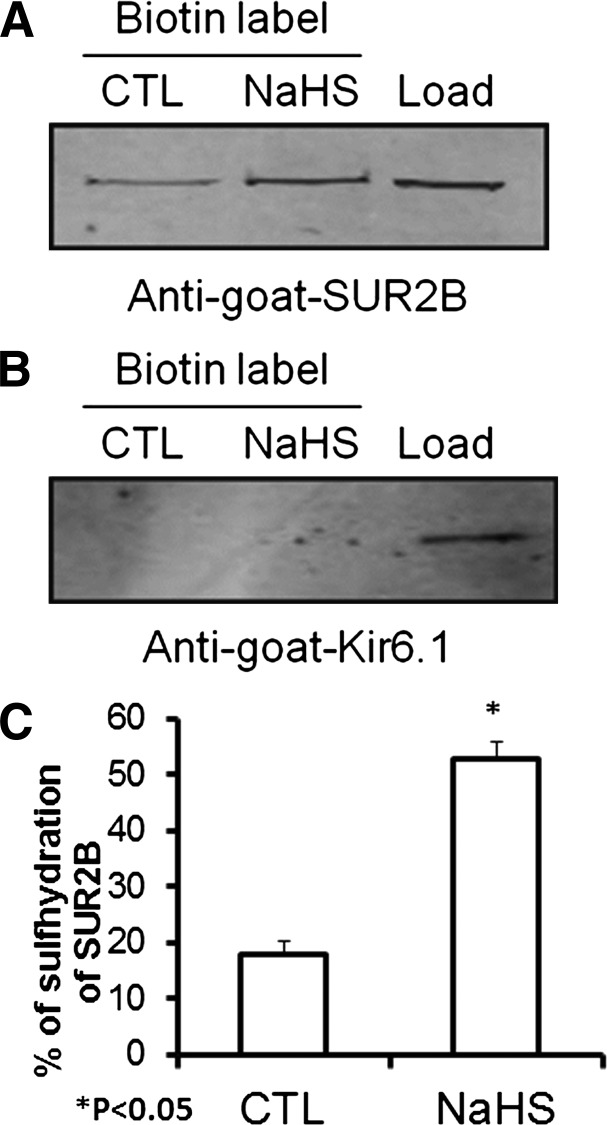

Because sulfhydration is known as a primary mechanism through which H2S signals, we examined the sulfhydration levels in KATP channels of colonic smooth muscle cell after treatment with 1 mM NaHS using a Biotin Switch Assay. There was some basal sulfhydration of the SUR2B subunit of the KATP channel that was enhanced upon treatment with 1 mM NaHS (Fig. 10, A and B). The enhanced sulfhydration of SUR2B was also seen in inflamed colon without any treatment with NaHS (Fig. 10C). In Chinese hamster ovary cells heterologously expressing Kir6.1 and SUR2B, sulfhydration was evident for SUR2B but not the Kir6.1 subunit (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10.

(A) Western blot showing the difference in the sulfhydration levels in the controls and after treatment with 1 mM of NaHS in mouse colon tissue. (B) quantified data demonstrating the difference in the amount of sulfhydration of the SUR2B subunit of the KATP channel in control and after treatment with 1 mM NaHS in mouse colon tissue. (C) Western blot showing the difference in the sulfhydration levels in the control and in inflamed mouse colon tissue. CTL, control; INF, inflamed; WB, Western blot.

Fig. 11.

(A) Western blot showing the difference in the sulfhydration levels in the controls and after treatment with 1 mM of NaHS in SUR2B but not Kir6.2 subunit–transfected KATP channel. (B) quantified data demonstrating the difference in the amount of sulfhydration of the SUR2B subunit of the KATP channel in controls and after treatment with 1 mM NaHS in transfected KATP channel (data normalized to the load value). CTL, control.

Discussion

The importance of H2S as a gaseous signaling molecule has been recognized in various physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions (Mustafa et al., 2009). In colonic inflammation, the protective role of H2S has been, in part, attributed to modulation of the ATP-sensitive potassium channels (Wallace et al., 2009). In the present study, we have found that 1) the potency and efficacy of the KATP channel opener, LEVC, is enhanced during colonic inflammation; 2) similarly, H2S-induced activation of the channel is also enhanced in inflamed cells; 3) H2S modifies the activation of LEVC via an allosteric effect; and 4) H2S S-sulfhydrates the SUR2B subunit but not Kir6.1.

Previously, Jin et al. (2004) demonstrated, in a mouse colitis model, an increase in both the amplitude of whole cell KATP currents and in the bursting activity of single channel currents in colonic smooth muscle in the presence of LEVC. We compared the concentration-response relationship for LEVC in inflamed cells and identified that in addition to increase in maximal currents (efficacy), the potency for LEVC is significantly shifted after inflammation. Of note, the potency of glibenclamide-induced inhibition of the KATP channel complex was not altered with inflammation, although the potential binding sites for the channel opener and blocker are on the same subunit (i.e., the sulfonylurea receptor) (Mikhailov et al., 2001; Moreau et al., 2005). Similarly, the potency of H2S toward activation of the KATP channel is also enhanced after inflammation. Although the activation of KATP channel by hydrogen sulfide has been demonstrated in several studies (Cheng et al., 2004; Spiller et al., 2010; Zhong et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011;), the specific subunit that is affected is not entirely clear. In addition to its effects on KATP channels, H2S also modulates other ion channels, notably L- and T-type calcium channels, as well as Na+ channels. L-type Ca2+ channels are inhibited, whereas T-type channels are sensitized (Sun et al., 2008; Matsunami et al., 2012). In the human jejenum smooth muscle cells, H2S enhanced Na+ influx through Nav1.5 via a redox-independent mechanism (Strege et al., 2011). S-sulfhydration of cysteine residues by H2S has been established as a posttranslational modification altering protein function. Mustafa et al. (2011) demonstrated sulfhydration of Cys43 of Kir6.1 as the potential site for H2S-induced enhancement of KATP channel activity. On the other hand, Jiang et al. (2010) found that in HEK cells, expression of rvSUR1 subunit was necessary for H2S-induced activation of K+ currents and replacement of extracellular Cys6 and Cys26 abolished channel sensitivity to H2S. We found that in colonic smooth muscle and in heterologously transfected cells, SUR2B was sulfhydrated by exogenous H2S, alluding to the possibility that posttranslational modification of the sulfonylurea receptor during inflammation alters the sensitivity to potassium channel opener. S-sulfhdyration appears to induce an allosteric effect on the activation of KATP channels. This was evident when in the presence of low concentrations of H2S the potency of LEVC is enhanced, an effect that is similar to inflammation. S-sulfhydration of the SUR2B subunit was also enhanced after colonic inflammation. Allosteric modulation of ion channels by endogenous signaling molecules including ATP, H2O2, glycine have been well described (Cui and Fan, 2002; Hogg et al., 2005; Chuang and Lin, 2009). Cui et al. suggested the modulation of KATP channel activity through sulfhydration of the cysteine residue of the Kir6.2 in heterologously expressed KATP channel (Cui and Fan, 2002). These studies demonstrated an allosteric block due to sulfhydration of extracellular cysteine residue. Our findings indicate that sulfhydration of SUR2B during colonic inflammation accounts for the enhanced sensitivity to KATP channel opener S-sulfhydration may result from enhanced H2S production during inflammation both from sources within the lumen (i.e., enteric bacteria) and from endogenous production due to the enhanced activity of cystathionine-β-synthase and cystathionine-γ-lyase. It is noteworthy that breakdown of mucosal barrier in colitis could further exaggerate the exposure of smooth muscle to the levels of H2S. In summary, the present study provides evidence of allosteric modulation through s-sulfhydration as a mechanism by which KATP channel activity is enhanced during colonic inflammation.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Kazuharu Frutani, Osaka University for providing us with mouse SUR2B cDNA.

Abbreviations

- HENS

HEPES-NaOH

- KATP

ATP-sensitive potassium channel

- LEVC

levcromakalim

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- SUR2B

sulfonylurea receptor

- TNBS

trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Gade, Kang, Akbarali.

Conducted experiments: Gade, Kang, Akbarali.

Performed data analysis: Gade, Kang, Akbarali.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Gade, Kang, Akbarali.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant DK046367].

References

- Akbarali HI, G Hawkins E, Ross GR, and Kang M (2010) Ion channel remodeling in gastrointestinal inflammation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 22:1045–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Babenko AP, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. (1998) A view of sur/KIR6.X, KATP channels. Annu Rev Physiol 60:667–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Ndisang JF, Tang G, Cao K, Wang R. (2004) Hydrogen sulfide-induced relaxation of resistance mesenteric artery beds of rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287:H2316–H2323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang HH, Lin S. (2009) Oxidative challenges sensitize the capsaicin receptor by covalent cysteine modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:20097–20102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SM. (1996) The immunomodulation of enteric neuromuscular function: implications for motility and inflammatory disorders. Gastroenterology 111:1683–1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Fan Z. (2002) Mechanism of Kir6.2 channel inhibition by sulfhydryl modification: pore block or allosteric gating? J Physiol 540:731–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg RC, Buisson B, Bertrand D. (2005) Allosteric modulation of ligand-gated ion channels. Biochem Pharmacol 70:1267–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B, Tang G, Cao K, Wu L, Wang R. (2010) Molecular mechanism for H(2)S-induced activation of K(ATP) channels. Antioxid Redox Signal 12:1167–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Malykhina AP, Lupu F, Akbarali HI. (2004) Altered gene expression and increased bursting activity of colonic smooth muscle ATP-sensitive K+ channels in experimental colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287:G274–G285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SD, Bradley KK, Rae MG, Keef KD, Horowitz B, Sanders KM. (1998) Basal activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in murine colonic smooth muscle cell. Biophys J 75:1793–1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang GH, Adebiyi A, Leo MD, McNally EM, Leffler CW, Jaggar JH. (2011) Hydrogen sulfide dilates cerebral arterioles by activating smooth muscle cell plasma membrane KATP channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300:H2088–H2095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden DR, Levitt MD, Farrugia G, Szurszewski JH. (2010) Endogenous production of H2S in the gastrointestinal tract: still in search of a physiologic function. Antioxid Redox Signal 12:1135–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WQ, Chai C, Li XY, Yuan WJ, Wang WZ, Lu Y. (2011) The cardiovascular effects of central hydrogen sulfide are related to K(ATP) channels activation. Physiol Res 60:729–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Rusch NJ, Striessnig J, Sarna SK. (2001) Down-regulation of L-type calcium channels in inflamed circular smooth muscle cells of the canine colon. Gastroenterology 120:480–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunami M, Miki T, Nishiura K, Hayashi Y, Okawa Y, Nishikawa H, Sekiguchi F, Kubo L, Ozaki T, Tsujiuchi T, and Kawabata A (2012) Involvement of the endogenous hydrogen sulfide/Ca(v) 3.2 T-type Ca(2+) channel pathway in cystitis-related bladder pain in mice. Br J Pharmacol 167:917–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mikhailov MV, Mikhailova EA, Ashcroft SJ. (2001) Molecular structure of the glibenclamide binding site of the beta-cell K(ATP) channel. FEBS Lett 499:154–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau C, Prost AL, Dérand R, Vivaudou M. (2005) SUR, ABC proteins targeted by KATP channel openers. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38:951–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Sen N, Kim S, Mu W, Gazi SK, Barrow RK, Yang G, Wang R, Snyder SH. (2009) H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci Signal 2:ra72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa AK, Sikka G, Gazi SK, et al. (2011) Hydrogen sulfide as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor sulfhydrates potassium channels. Circ Res 109:1259–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers BS, Martin JS, Dempsey DT, Parkman HP, Thomas RM, Ryan JP. (1997) Acute experimental colitis decreases colonic circular smooth muscle contractility in rats. Am J Physiol 273:G928–G936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzone MA, Wald A. (2002) Functional bowel disorders in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 31:347–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky DK. (1999) Inflammatory bowel disease 1999: present and future promises. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 15:283–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SN, Bazzocchi G, Chan S, Akashi K, Villanueva-Meyer J, Yanni G, Mena I, Snape WJ., Jr (1991) Colonic motility and transit in health and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 101:1289–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross GR, Kang M, Akbarali HI. (2010) Colonic inflammation alters Src kinase-dependent gating properties of single Ca2+ channels via tyrosine nitration. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298:G976–G984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snape WJ, Jr, Kao HW. (1988) Role of inflammatory mediators in colonic smooth muscle function in ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci 33(3, Suppl)65S–70S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller F, Orrico MI, Nascimento DC, et al. (2010) Hydrogen sulfide improves neutrophil migration and survival in sepsis via K+ATP channel activation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182:360–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strege PR, Bernard CE, Kraichely RE, et al. (2011) Hydrogen sulfide is a partially redox-independent activator of the human jejunum Na+ channel, Nav1.5. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300:G1105–G1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YG, Cao YX, Wang WW, Ma SF, Yao T, Zhu YC. (2008) Hydrogen sulphide is an inhibitor of L-type calcium channels and mechanical contraction in rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res 79:632–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JL, Ferraz JG, Muscara MN. (2012) Hydrogen sulfide: an endogenous mediator of resolution of inflammation and injury. Antioxid Redox Signal 17:58–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JL, Vong L, McKnight W, Dicay M, and Martin GR (2009) Endogenous and exogenous hydrogen sulfide promotes resolution of colitis in rats. Gastroenterology 137:569–578 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Whiteman M and Winyard PG (2011) Hydrogen sulfide and inflammation: the good, the bad, the ugly and the promising. Exp Rev Clin Pharmacol 4:13–32 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhong GZ, Li YB, Liu XL, Guo LS, Chen ML, Yang XC. (2010) Hydrogen sulfide opens the KATP channel on rat atrial and ventricular myocytes. Cardiology 115:120–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]