Abstract

Positive outcomes of antimicrobial stewardship programs in the inpatient setting have been well documented, but the benefits for patients not admitted to the hospital remain less clear. This report describes a retrospective case-control study of patients discharged from the ED with subsequent positive cultures conducted to determine if integrating antimicrobial stewardship responsibilities into practice of the dedicated emergency medicine clinical pharmacist (EPh) decreased times to positive culture follow-up, patient or primary care provider (PCP) notification, and appropriateness of empiric or final antimicrobial therapy for patients discharged from the emergency department (ED). Pre-and post-implementation groups of an EPh-managed antimicrobial stewardship program were compared. Data were collected from medical records and the ED culture database. Continuous data were analyzed using Wilcoxon Rank Sum test and categorical data using Chi-squared analysis.

Positive cultures were identified in 177 patients, 104 and 73 in pre and post-implementation groups, respectively. Median time to culture review in the pre-implementation group was 3 days (range 1–15) and 2 days (range 0–4) in the post-implementation group (p=0.0001). There were positive cultures that required notification in 74 (71.2%) and 36 (49.3%) on pre- and post-implementation groups, respectively. Median time to patient or PCP notification was 3 days (range 1–9) in the pre-implementation group and 2 days(range 0–4) in the Eph managed program (p = 0.01). No difference in appropriate antimicrobial therapy was seen.

INTRODUCTION

Multi-drug resistant pathogens are a growing concern when treating nosocomial and community-associated infections.1 These resistant organisms are associated with increased morbidity, mortality and costs.1 Antimicrobial stewardship programs, are one method that can be used to control the rise in resistance and improve the quality of patient care. In addition, inappropriate empiric antibiotic therapy may lead to readmission to the hospital and complications for the patient, secondary to infection. The incorporation of a clinical pharmacist on an antimicrobial stewardship service is supported by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America in their 2007 antimicrobial stewardship guidelines.1 It is stated that pharmacists play a crucial role in antimicrobial stewardship as they are knowledgeable on the appropriate use of antimicrobials, dosing, and drug interactions.1

One area with a growing pharmacy presence is the emergency department (ED). Recently, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists' (ASHP) issued a draft statement on the role of pharmacists in the ED stating that “pharmacists are integral to the provision of interdisciplinary patient care services. A wide variety of services can be provided by pharmacists in this practice setting, and these include providing essential patient care, managing medication services, patient and health care provider education, contributing to quality improvement initiatives, and participating in research.”2 Research has shown that pharmacists play an important role in the ED, but there is a need for data supporting this in specific patient outcomes as the majority of the literature addresses adverse drug event prevention and cost-containment.3–6

Therefore, a logical expansion of services provided by the EPh is involvement in antimicrobial stewardship activities. However, this has not been extensively studied and consequently limited data are available. A previous report described a pharmacist-managed antimicrobial stewardship program from the ED, however to date; limited data is available on the effect of such a program.7–8 Randolph, et al compared one year of physician-managed cultures (n=2,278) to one year of pharmacist-managed cultures (n=2,361) in the ED setting. This retrospective review revealed that EPh made more antimicrobial regimen modifications and reduced the rate of unplanned admissions in 96 hours of initial culture review, allergic reactions, and compliance.8

In response to provider demand, a similar program in our ED was launched. There are currently limited data that support the clinical impact for this novel role of the EPh. An aspect that has not been previously evaluated is the impact of time to culture review and change in therapy or provider notification. There is data in the inpatient setting that reveal time to appropriate antibiotics does play a role in patient outcomes.9–11 The purpose of this investigation was to compare the times to culture follow-up and patient or provider notification and appropriate antimicrobial therapy before and after an EPh-managed antimicrobial stewardship program.

METHODS

Setting

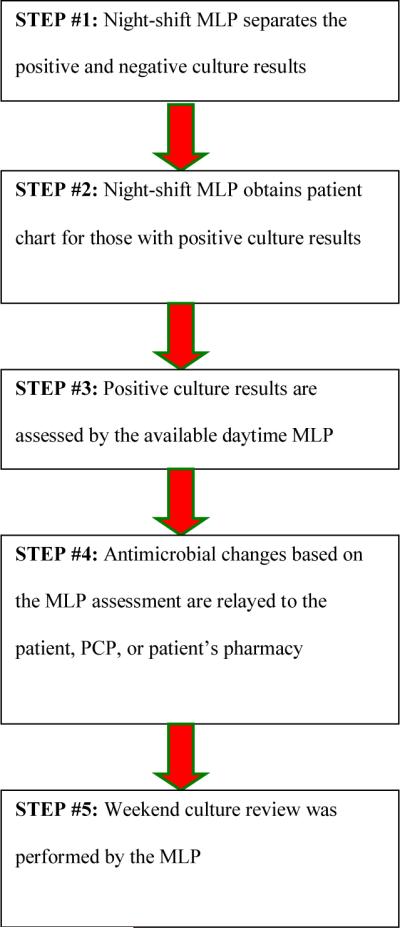

This study was conducted at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC), a university teaching hospital providing emergency services of over 97,000 visits per year. Prior to EPh involvement, the emergency medicine mid-level providers (MLP), nurse practitioners and physician assistants, were responsible during their clinical shifts for antimicrobial culture and susceptibility report follow-up for patients who were previously discharged directly from the ED (Figure 1). Owing to high daily patient volume, routine screening of culture reports often fell to the end of the daily task list and was identified by the MLPs as an area needing improvement. The EPh was requested to assist in this process given their role in ensuring appropriateness of medication therapies in the ED and knowledge of antimicrobial therapy through Pharm.D. curriculum and advanced residency training. An EPh-managed antimicrobial stewardship program in the ED commenced in October 2008.

Figure 1.

Pre-Implementation Culture and Susceptibility Follow-Up Process

Abbreviations: MLP, mid-level providers; EPH, emergency medicine clinical pharmacist; PCP, primary care provider

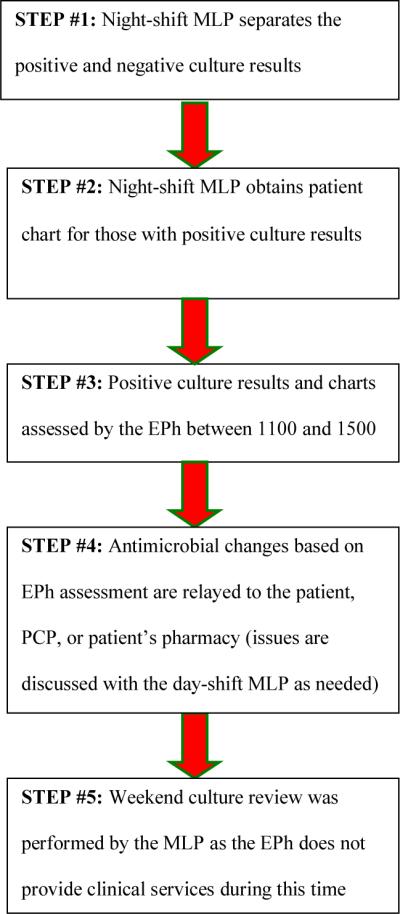

EPh involvement has two key components: education regarding appropriate empiric antimicrobial selection and assistance with follow-up to identify patients where a change in therapy is required. The educational component involved didactic lectures and preparation of clinical resources to be used when the Eph was unavailable. The active surveillance component was incorporated into daily activities of the EPh beginning October 1, 2008 (Figure 2). It is important to note that the steps in the process did not change, but some of the responsibility was transitioned to the Eph. The workflow for the process was based on a daily set of culture reports generated by the microbiology laboratory at 0300. The system relies on overnight staff collating necessary clinical information (pulling the chart etc) for review and follow-up during the day shift. The Eph assumed the responsibility of reviewing these culture results and providing necessary follow-up. This was a dedicated activity that occurred during normal business hours when follow-up contact is more practical. In addition to culture review, the Eph assumed responsibility for all telephone reports (from the microbiology laboratory as well as follow-up calls from patients and providers). It was estimated the additional work load for the Eph was somewhere between 1.5–3 hours daily.

Figure 2.

Post-Implementation Culture and Susceptibility Follow-Up Process

Abbreviations: MLP, mid-level providers; EPH, emergency medicine clinical pharmacist; PCP, primary care provider

Study Population

In order to assess the impact of the EPh-managed antimicrobial stewardship program, a retrospective cohort of all adult patients that were discharged from the ED with subsequent positive culture results between two time periods were evaluated. Pre-implementation was the time period of November 2007 through January 2008 and post-implementation of an EPh-managed program was from November 2008 through January 2009.

Patients were identified, retrospectively, from ED antimicrobial culture and susceptibility follow-up database that was maintained by the MLP and EPh. All patients from the pre- and post-implementation time periods who were > 18 years old and had a reported positive culture after discharge from the ED were included in the analysis. This included subjects who were transferred to another institution or admitted to the 23 hour observational unit. Patients who were admitted to in-patient status were excluded.

Data Collection

Prior to initiation of data collection, approval was obtained from the URMC research subjects review board.. A complete culture database and medical record review was conducted by one abstractor using a standardized abstraction form and code book to gather cultures drawn, culture results including susceptibility data, empiric antimicrobial selection and changes made to therapy following discharge, time to positive culture review, time to patient or PCP notification, and time to appropriate antibiotic therapy based on final culture results. The time to positive culture review was defined as the time from patient presentation to the ED, utilizing documented triage date, to the first time the positive culture was reviewed. The time of review was documented in the culture database as a date without a time. Therefore the results are reported in days.

Antimicrobial therapy was deemed inappropriate by the data abstractor if: (1) the empiric antibiotic prescribed to the patient would not treat the presumed/documented pathogen based on the reported spectrum of activity, (2) empiric recommendation was inconsistent with IDSA or local guidelines for the patient's infectious process, or (3) local data implies that the initial therapy was inappropriate (e.g. institution-specific antibiogram). However, once positive culture results and susceptibilities were final, antimicrobial therapy was assessed based on this information in combination with the clinical indication for therapy and susceptibility results for the identified pathogen, when available. Appropriateness during culture review was determined by the EPh. For those that were more complex, the infectious diseases clinical pharmacy specialist was consulted.

Data Analysis

The primary endpoints of time to positive culture review as well as time to patient or PCP notification were analyzed using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. The secondary endpoindpoings of appropriateness of antimicrobial therapy as empiric and definitive treatment were presented as categorical data and compared using the Chi-square analysis or Fisher's exact test where appropriate.

A target sample size was calculated using PS software Version 3.0 (Power and Sample Size Calculations). At a desired alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.8, a sample size of 200 patients for each study group was calculated to be adequate to detect a ≥ 30% reduction in time to positive culture review.

RESULTS

A total of 212 patients with subsequent positive cultures were identified during the study period, 132 in the pre-implementation group (11/2007–1/2008) and 80 in the post-implementation group (11/2008–1/2009). Twenty-eight patients in the pre-implementation group and seven patients in the post-implementation group were excluded due to subsequent hospital admission, resulting in 104 in the pre-implementation and 73 in the post-implementation groups.

Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between the two groups (Table 1). However, positive urine cultures were more common among those in the pre-implementation group (p=0.05) whereas the post-implementation group had more positive skin and soft tissue cultures (p=0.03).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics

| Pre-Implementation (n = 132) | Post-Implementation (n = 80) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Median age (range), years | 51.5 (18–95) | 48.5 (18–93) | 0.32 |

|

| |||

| Male, no. (%) patients | 67 (50.8) | 31 (38.8) | 0.09 |

|

| |||

| Antimicrobial allergies, no. (%) patients* | 35 (26.5) | 27 (33.8) | - |

|

| |||

| Positive cultures, no. (%) | |||

| Blood | 80 (60.6) | 50 (62.5) | 0.78 |

| Urinary Tract | 71 (53.8) | 32 (40) | 0.05 |

| Skin Soft Tissue | 24 (18.2) | 25 (31.3) | 0.03 |

| Genitourinary | 9 (6.8) | 3 (3.8) | 0.35 |

| Upper Respiratory | 7 (5.3) | 7 (8.8) | 0.33 |

| Sputum | 4 (3) | 1 (1.3) | 0.41 |

| Miscellaneous | 17 (12.9) | 7 (8.8) | 0.36 |

Patients may have had more than one allergy

The median time to positive culture review following collection in the pre-implementation group was 3 days (range 1–15) compared to 2 days (range 0–4) in the post-implementation group (p=0.0001) (Table 2). Not all patients with positive cultures required PCP or patient notification due to appropriate empiric treatment given in the ED. The median time to patient or PCP notification was 3 days (range 1–9) for pre-implementation group compared to 2 days (range 0–4) for the post implementation, p=0.01. There were no statistically significant differences for the secondary outcomes. Empiric antimicrobial therapy was appropriate for 88.9% of the cultures in the pre-implementation group and for 87% of the cultures in the post-implementation group (p=0.75). Final antimicrobial therapy was appropriate for 95.7% of the cultures in the pre-implementation group and for 100% of the cultures in the post-implementation group (p=0.1). Patients were only included in the final antimicrobial therapy assessment if their therapy was not changed (i.e. patient remained on same antibiotic that was started empirically) or if changes to their antimicrobial regimen were known.

Table 2.

Study Results

| Pre-Implementation | Post-Implementation | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Primary Endpoints: | |||

|

| |||

| Time to Positive Culture Review (median days, range) | 3 (1–15) | 2 (0–4) | 0.0001 |

| (n = 104) | (n = 73) | ||

|

| |||

| Time to Patient or PCP Notification (median days, range) |

3 (1–9) | 2 (0–4) | 0.01 |

| (n = 74) | (n = 36) | ||

|

| |||

| Secondary Endpoints: | |||

|

| |||

| Appropriate Empiric Therapy (%) | 64 (88.9) | 40 (87) | 0.75 |

| (n=72) | (n=46) | ||

|

| |||

| Appropriate Final Therapy (%) | 66 (95.7) | 61 (100) | 0.10 |

| (n=69) | (n=61) | ||

Abbreviations: PCP, primary care provider

DISCUSSION

Antimicrobial agents are commonly prescribed to patients who are discharged from the ED. However, there is often limited or inconsistent follow-up of culture results to systematically ensure appropriate therapy. Given the previous success of pharmacy-managed antimicrobial stewardship programs in the inpatient setting, it is logical to consider integration of ED-based stewardship into the practice of the Eph. . This retrospective case-control study with a historical control group was designed to evaluate the impact of the dedicated emergency medicine clinical pharmacist on the time to positive culture review and patient or provider notification for patients discharged from a busy ED at an academic medical center. We found that an EPh-managed program decreased both time to positive culture review and time to patient or PCP notification when indicated. Although our study was not able to specifically evaluate the clinical outcome associated with delays in appropriate antimicrobial therapy, there is evidence in the in-patient setting that these delays are associated with worse clinical outcomes.9–11

During the pre-implementation period, the MLPs prioritized their tasks based on the ED patient census, so when the ED was busy, the review of the positive culture and susceptibility information were often delayed until later in the day or several days later. Since the MLPs did not have control over the ED patient census or the number of positive culture and susceptibility reports, systematic and timely follow-up was inconsistent. The EPh is ideally positioned to maintain the task as a high priority, and has the knowledge and skills necessary to manage the culture results.

There are limitations to our study that need to be considered. During the post-implementation time period, the microbiology culture report was incomplete as certain types of cultures did not print for several days due to technological issues. The EPh collaborated with the microbiology lab and information technology services to remedy this issue, but this had a negative impact on the sample size for the post-implementation group and limited our power to detect a meaningful difference. There was also a difference in the site of the positive cultures in the two patient groups. We intentionally selected the same months for pre- and post-implementation cohorts to account for seasonal variation in infectious processes and believe these differences are due to chance. The time to growth and reporting of both urine and skin and soft tissue infections is generally two days at our institution and there are well developed empiric treatment guidelines for these infections, making them reasonable infections to compare. In addition, no new assays or techniques were implemented by the microbiology lab between the two periods of study that would have altered turnaround time in culture results. We do not feel that this difference in the patient groups impacted the time dependent endpoints.

Another limitation is that the EPh at our institution is available Monday through Friday from 1100 to 1900, so the MLPs are still responsible for culture follow-up on the weekends. This is reflected in the time dependent endpoints in the post-implementation group where the range was reported up to 4 days. Cultures that printed Saturday at 0300 may not have been reviewed until Monday at 1100 if the MLPs were unavailable for review. Lastly, based on the design of the ED antimicrobial stewardship program we currently only capture patients with subsequent positive cultures following discharge from the ED and not all patients that have received treatment with antibiotics. Based on this current model we are unable to address the discontinuation of unnecessary antimicrobial therapy or optimization of therapy for patients who are prescribed broad-spectrum agents that may not be necessary. This is an initiative that we will explore implementing in the future. Finally, we were unable to assess efficacy and adherence to antimicrobial regimens.

CONCLUSION

An EPh-managed antimicrobial stewardship program significantly reduced time to positive culture review and time to patient or PCP notification when indicated. Further study is necessary to determine whether this impacts patient outcomes in the ED setting.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Foundation, Pharmacy Resident Practice-Based Research Grant. Dr. Fairbanks is supported by a Career Development Award from the NIBIB (1K08EB009090).

REFERENCES

- 1.Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. CID. 2007;44:159–177. doi: 10.1086/510393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists ASHP statement on pharmacy services to the emergency department. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008;65:2380–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elenbaas RM, Waeckerle JF, McNabney WK. The clinical pharmacist in emergency medicine. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1977;34:843–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fairbanks RJ, Hays DP, Webster DF, et al. Clinical pharmacy services in an emergency department. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2004;61:934–937. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.9.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly S, Hays D, O'Brien T, et al. Pharmacist participation in trauma resuscitation. The 40th Annual American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Midyear Clinical Meeting 2005; Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Medical Center, Strong Health; abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acquisto NM, Hays DP, Fairbanks RJ, et al. The outcomes of emergency pharmacist participation during acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Emergency Medicine. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.06.011. Avalable online,Sept 2010, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Wymore ES, Casanova TJ, Broekemeier RL, et al. Clinical pharmacist's daily role in the emergency department of a community hospital. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008;65:395–399. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Randolph TC, Parker A, Meyer L, et al. Enhancing antimicrobial therapy through a pharmacist-managed culture review process in an emergency department setting. The 44th Annual American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Midyear Clinical Meeting 2009; Concord, NC: Carolinas Medical Center – Northeast; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood K, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1589–1596. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garey KW. Timing of fluconazole therapy and mortality in patients with candidemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:25–31. doi: 10.1086/504810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaieski DF, Pines JM, Band RA, et al. Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1045–1053. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cc4824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert DN, Moellering RC, Elopoulos GM, et al. The Sanford guide to antimicrobial therapy. 40th edition 2010. [Google Scholar]