Neuroticism is a stable personality trait reflecting a tendency to experience negative emotional responses, including symptoms such as irritability, sadness, and anxiety [7], and has been linked with negative physical health outcomes [21, 28]. There is now renewed interest in the relationship of neuroticism to pain, particularly in pediatric populations [13, 17, 24]. Although neuroticism is considered a higher order personality trait (a broad construct describing a general characteristic, which is made up of specific and unique facets, known as lower order factors), some have hypothesized that neuroticism may impact pain responses through its effects on lower-order factors, such as pain-related cognitive and behavioral processes [2, 21]. One of these factors, pain catastrophizing, has been shown to mediate relationships between negative affect (i.e., neuroticism) and somatic complaints and functional disability [36]. These data suggest that pain-specific factors, in addition to higher order personality traits, are both critical to helping understand pain and disability.

In particular, anxiety sensitivity (AS), or the tendency to fear the physical sensations of anxiety, has been established as a predictor of both acute [18, 19, 30, 33–35] and chronic pain [31]. AS has been found to be more predictive of acute pain responses than higher-order traits such as neuroticism in adults [22]. Among children, we previously found strong relationships between AS and acute pain responses [33–35]; although, the relationships among neuroticism, AS, and pain responses have not been tested in children. Furthermore, evidence suggests that AS appears to be a distinct construct from other cognitive, pain-related constructs such as pain catastrophizing or pain anxiety [25], and therefore may help better explain the relationships of negative affect and pain responses beyond those already previously reported [36].

Understanding these relationships may have profound implications for treatment. The treatment of neuroticism has primarily been addressed through psychopharmacological approaches [9, 20], with one study in adults with major depressive disorder finding that levels of neuroticism were significantly lower after a trial of paroxetine, even after controlling for improvements in depression [29], whereas cognitive therapy did not produce changes in neuroticism, when depression levels were controlled. On the other hand, AS has been shown to be responsive to cognitive behavioral interventions [19, 39], and reductions in AS may lead to reductions in pain through cognitive mechanisms, such as pain-related anxiety. Taken together, these findings suggest that lower-order factors may be more amenable to behavioral approaches than higher order factors such as neuroticism. Among children, concerns regarding medication side effects on the developing neurobiological system underscore the need to delineate pathways for effective treatment.

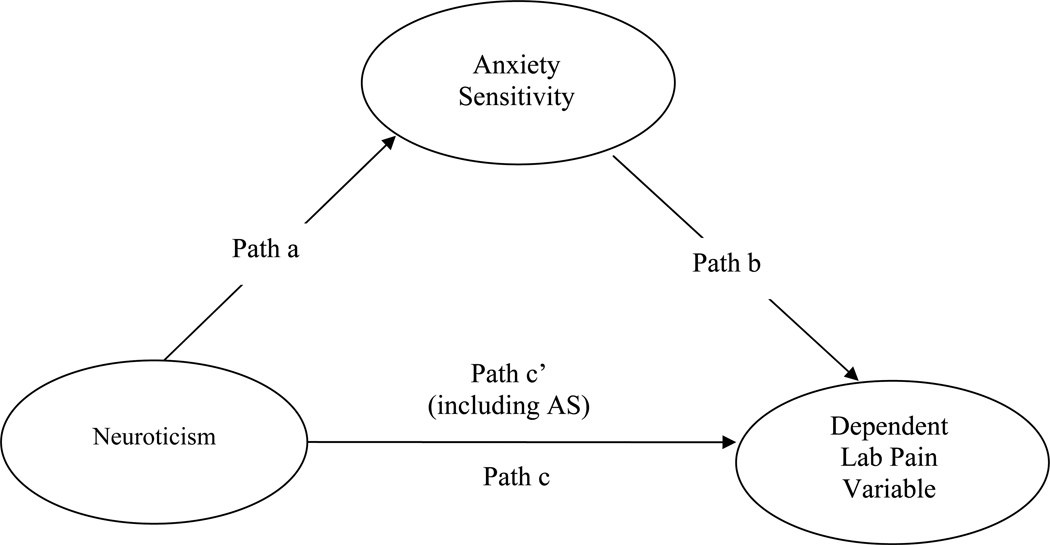

The current study aimed to examine the relationship between neuroticism, AS, and acute pain responses (anticipatory anxiety, pain intensity, and pain bother) to a series of standardized laboratory pain tasks involving cold and pressure pain in a sample of non-clinical children by testing whether AS mediates the neuroticism-pain relationship (see Figure 1). We hypothesized that neuroticism and AS would be correlated with acute pain responses, but AS would at least partly mediate the relationship between neuroticism and pain responses.

Figure 1. Mediational models of neuroticism, anxiety sensitivity, and dependent laboratory pain variables.

Both neuroticism, a higher-order, stable personality trait, and anxiety sensitivity (AS), a lower-order pain-related construct, have been associated with pain, although no research exists examining the relationship of both these constructs to acute pain in children. In the current study, 99 non-clinical children (53 girls) completed self-report measures of neuroticism and anxiety sensitivity prior to undergoing pain tasks involving cold and pressure pain. We hypothesized that both neuroticism and AS would be correlated with acute pain responses, but that AS would at least partly mediate the relationship between neuroticism and pain responses. Results indicated significant correlations between neuroticism, AS, and anticipatory anxiety, pain intensity and pain bother. Mediational models revealed that AS partially mediated relationships between neuroticism and pain intensity/bother, and fully mediated relationships between neuroticism and anticipatory anxiety. These data suggest that, at least in children, neuroticism may be best understood as a vulnerability factor for elevated pain responses, especially when coupled with a fear of bodily sensations.

Both neuroticism and anxiety sensitivity share strong relationships with laboratory pain responses, although anxiety sensitivity at least partly explains the relationship between neuroticism and pain across most tasks.

Method

Participants

The data for the current study were drawn from a larger investigation examining the influences of sex and puberty on acute pain responses in children and adolescents with and without chronic pain. The present study only included children without chronic pain. At least one parent of each participating child also took part in a laboratory session at the same time as their child but the parent data are not reported herein. Participants for the current study were 99 non-clinical children and adolescents (53 female, 53.5%), with a mean age of 13.5 years (SD = 2.8, range = 8–17) (see Table 1). The broad age range was designed to include youth at various stages of puberty from pre-pubescent through adolescence. Demographic statistics, including race/ethnicity, are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information for study participants.

| Characteristic | Total Sample (N = 99) |

|---|---|

| Female, no. (%) | 53 (53.5) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 13.5 (2.8) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic/Non-Latino | 72 (72.7) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 27 (27.3) |

| Race, no. (%)* | |

| White | 51 (51.5) |

| African American | 20 (20.2) |

| Asian | 2 (2.0) |

| Multi-Racial | 23 (23.2) |

Race was unavailable for 3 participants.

One hundred forty-five families were screened for eligibility by telephone, but 5 children (3.4% of those screened) were excluded due to acute or chronic illness, use of medications that could affect study outcomes, or developmental delay. Of the 140 (96.6%) invited to participate, 34 (24.5%) declined participation mainly because of lack of interest or scheduling difficulties. Six participants had incomplete data and were excluded from the analyses described herein. Written informed consent forms were completed by parents, and children provided written assent. The study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board. Each child received $50 cash for their participation.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through posted advertisements, community events, and through referrals from previous participants. Study advertisements were posted on online forums (e.g., Craigslist, local Yahoo groups, etc.) as well as at locations where parents and children would be expected to encounter them (e.g., libraries, pediatricians’ offices, etc.). Study staff also attended various community events (festivals/fairs, farmers’ markets, 5K runs, etc.) to pass out fliers and get contact information for interested families. Also, previous participants were offered the opportunity to refer their friends/neighbors and earn an additional $25 for each referred family that completed the study.

Eligibility was confirmed by telephone. A trained research assistant asked parents whether they or their child met any of the following exclusionary criteria: acute illness or injury that may potentially impact lab performance (e.g., fever, flu symptoms), or that affected sensitivity of the extremities (e.g., Reynaud’s disease, hand injuries); daily use of opioids at the time of study participation; or developmental delay, autism, or significant anatomic impairment that could preclude understanding of study procedures or participation in pain induction procedures. If the family had more than one child that met inclusion criteria, only one child per family was enrolled in the study.

Upon arrival to the laboratory, participants were greeted and escorted to separate rooms; there was no contact between parent and child until after the session was completed. Participants provided informed consent/assent and then completed questionnaires using an online website. Only those questionnaires relevant to the current study are discussed herein. Child participants were interviewed by a research assistant about their recent pain history and for girls, menstrual history.

Child participants were then escorted into the laboratory where their height and weight were recorded, medication use for that day was assessed, and leads for physiological recording were attached. (Physiological data were continuously recorded during the laboratory session but will be presented in a separate report). Participants were shown the 0 (none) to 10 (worst or most possible) Numerical Rating Scale (NRS, described below) and instructed on its use. These endpoints were identical for all NRS-related questions about anticipatory anxiety, pain intensity, and pain bother. Participants were told that they would be using the NRS to indicate how they felt at different times during the study. Practice items for the NRS were administered (described below) to ensure participants understood the scale. Then followed a 5 minute habituation period for recording of baseline physiology during which participants were instructed to sit quietly and to watch a neutral nature video with no sound. Participants were then administered the pain induction tasks in the following order: evoked pressure (EP), cold pressor (CP), and tonic pressure (TP) (described below). (An additional pain task was then administered but will be presented in a separate report). In our previous experimental pain study using similar laboratory pain tasks we counterbalanced the order of tasks but found no order effects [35]. Thus, the tasks were administered in a standardized order across all participants. Each task was separated by an inter-task interval of between 3 – 5 minutes. Prior to the start of each task, participants were given instructions for the task and were given the opportunity to ask questions before beginning the task. After the completion of the final laboratory task, there was another 5-minute period during which participants were instructed to sit quietly for recording of post-baseline physiology. Physiological recording equipment was then removed and subjects were escorted out of the laboratory and paid for their participation.

Laboratory Pain Tasks

Evoked Pressure (EP)

To assess pressure pain sensitivity and threshold, we used a procedure developed by Dr. Richard Gracely [14] in which discrete 5-second pressure stimuli were applied to the fixated thumbnail of the left hand with a 1 × 1 cm hard rubber probe. The rubber probe was attached to a hydraulic piston, which was controlled by a computer-activated pump to provide repeatable pressure-pain stimuli of rectangular waveform. The EP task consisted of two parts. First, a series of stimuli was presented in a predictable, “ascending” manner, beginning at .066 kg/cm2 and increasing in .132 kg/cm2 intervals up to the participant’s report of moderate pain (a 6 NRS rating) or to a maximum of 1.12 kg/cm2 (EP ASC). Then, stimuli were delivered at 15-second intervals in random order, using the multiple random-staircase (EP MRS) pressure-pain sensitivity method [15]. The MRS method is response dependent, i.e., it determines the stimulus intensity needed to elicit a specified response. We used two thresholds: ‘mild pain’ (3/10) and ‘moderate pain’ (6/10 pain scale). Thus, this procedure resulted in two separate measures of pain sensitivity: one just above absolute pain threshold and one at the higher moderate pain level. A major advantage of the MRS technique is that a minimum of stimuli are delivered above the highest threshold and none are delivered more than .5 kg/cm2 above the threshold, since ratings of moderate pain lead to decreased pressure given on the next trial of the particular staircase. The EP MRS procedure was performed once. Low and high staircases were administered simultaneously, measuring mild pressure pain and moderate pressure pain thresholds, respectively. Stimuli are presented in random order between the two staircases. Completion of the procedure yields values for both staircases (i.e., mild and moderate pressure pain thresholds).

Cold Pressor (CP)

A single trial of the CP was administered. Participants placed the right hand in a cold pressor unit comprised of a Techne TE-10D Thermoregulator, B-8 Bath, and RU-200 Dip Cooler (Techne, Burlington, NJ). The unit maintained the water at a temperature of 5 degree Celsius and kept the water circulating to prevent localized warming around the hand. Recent research has shown 5 degrees Celsius to be an appropriate temperature for use with children and adolescents in the age range of the current study [8], and a recent systematic review suggests that using a temperature of less than 10 degrees Celsius in children older than 8 years may reduce the likelihood of a ceiling effect [4]. Participants’ hands were submerged up to approximately 2” above the wrist. Participants were instructed to keep their hand in the cold water for as long as they possibly could but that they could terminate the trial at any time. The task had an uninformed ceiling of 3 minutes. The administration of the cold pressor was in line with the guidelines set forth in previous systematic reviews [4, 37].

Tonic Pressure (TP)

The Ugo Basile Analgesy-Meter 37215 (Ugo Basile Biological Research Apparatus, Comerio, Italy) was used to administer a single trial of focal pressure through a dull lucite point approximately 1.5 mm in diameter to the second dorsal phalanx of the middle finger of the right hand. Participants were instructed to keep their finger under the pressure for as long as they possibly could, but that they could terminate the trial at any time. The task had an uninformed ceiling of 3 minutes.

Measures

Questionnaires

The Junior Eysenck Personality Questionnaire – Neuroticism subscale (JEPQ-N) [11]

The JEPQ was designed to assess the personality traits of psychoticism, extraversion, neuroticism, and social desirability. For the current study, we administered only the neuroticism subscale, which comprises 20 items that are responded to in a yes/no format, with higher scores (more “yes” answers) reflecting higher levels of neuroticism (total score range 0 – 20). The Neuroticism subscale of the JEPQ-N has demonstrated adequate to excellent reliability (rs .55 – .86) [5]. Internal consistency was high in the current sample (α = .82).

Children’s Anxiety Sensitivity Index (CASI) [27]

The CASI is an 18-item scale assessing the specific tendency to interpret anxiety sensations as dangerous. Items are scored on a 3-point scale (none, some, a lot), with total scores calculated by summing all items (total score range 18 – 54). Higher scores reflect greater endorsement of anxiety sensitivity. The CASI has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .87) and adequate test-retest reliability over 2 weeks (range = .62 – .78) [27]. Construct validity is supported by good correlations with measures of trait anxiety (rs = .55 – .69); however, the CASI also accounts for variance in fear that is not attributable to trait anxiety measures [40]. Internal consistency for the CASI in the current sample was adequate (α = .75).

Pain Task Measures

Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)

In order to assess comprehension of the NRS, six baseline items were administered: (1) “How much pain do you feel right now?”; (2) “How painful would it be to walk up 2 steps?”; (3) “How painful would it be to touch a hot stove?”; (4) “What might cause a 5 on this scale?”; (5) “How nervous, afraid, or worried do you feel right now?”; (6) “How nervous, afraid, or worried would you be before taking a test?”. If necessary, instructions for using the NRS and baseline items were repeated until participants fully understood the scale. The NRS (0–10 point scale) has been shown to be a reliable and valid method of assessing self-reported pain intensity in children as young as 8 years old [38].

Anticipatory Anxiety

Ratings of anticipatory anxiety were obtained immediately prior to each task (EP ASC, EP MRS, CP, and TP). Participants rated their responses to the following question: “How nervous, afraid, or worried are you about the upcoming task?” using the 0–10 NRS.

Pain Intensity

Immediately after each task, participants were asked to rate the level of pain experienced during the task using the 0–10 NRS. Participants were asked, “At its worst, how much pain did you feel during the task?”. Only one pain intensity rating was obtained at the end of the entire EP task (i.e., including both the EP ASC and the EP MRS).

Pain Bother

Immediately after the assessment of pain intensity for each task, participants were asked to rate how much the task bothered them using the 0–10 NRS. Participants were asked, “At its worse, how much did the [pain task] bother you?”. Only one pain bother rating was obtained at the end of the entire EP task.

Pain Tolerance

Pain tolerance (for the CP and TP tasks only) was defined as the amount of time, in seconds, elapsed from the onset of the pain stimulus to participants’ withdrawal from the stimulus. Before each task, participants were instructed to continue with the task for as long as they possibly could and that they should end the task (i.e., remove hand from water or signal to researcher to lift the pressure lever) when they could no longer continue the exposure to the stimulus. We found no significant relationships between pain tolerance and any of the study variables (all ps > .05), so these data will not be reported further.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for boys, girls, and the total sample across all study measures are provided in Table 2. There were no significant differences between boys and girls on any measure. Sample means for the CASI were within normative ranges for non-clinical children [27]. For the JEPQ-N, sample means for boys and girls were slightly lower than published norms for British and Canadian non-clinical boys and girls [11, 26].

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for study measures for boys, girls, and total sample.

| Boys (n=46) | Girls (n=53) | Total Sample (n=99) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range |

| JEPQ-N | 7.94 | 4.64 | 0–18 | 8.49 | 4.46 | 0–18 | 8.23 | 4.53 | 0–18 |

| CASI | 28.26 | 4.81 | 19–39 | 29.04 | 5.00 | 18–43 | 28.68 | 4.90 | 18–43 |

| Evoked Pressure (EP) | |||||||||

| anticipatory anxiety (ASC) | 3.11 | 2.43 | 0–10 | 3.79 | 2.79 | 0–10 | 3.47 | 2.639 | 0–10 |

| anticipatory anxiety (MRS) | 3.15 | 2.66 | 0–10 | 3.64 | 2.70 | 0–10 | 3.41 | 2.68 | 0–10 |

| pain intensity | 6.17 | 1.99 | 1–10 | 6.32 | 1.77 | 2–10 | 6.25 | 1.87 | 1–10 |

| pain bother | 4.26 | 2.73 | 0–10 | 4.51 | 2.20 | 0–10 | 4.39 | 2.45 | 0–10 |

| Cold Pressor (CP) | |||||||||

| anticipatory anxiety | 2.35 | 2.19 | 0–8 | 2.60 | 2.10 | 0–8 | 2.48 | 2.14 | 0–8 |

| pain intensity | 6.59 | 2.57 | 1–10 | 5.66 | 2.66 | 0–10 | 6.09 | 2.65 | 0–10 |

| pain bother | 5.61 | 2.80 | 0–10 | 5.75 | 2.95 | 0–10 | 5.69 | 2.87 | 0–10 |

| Tonic Pressure (TP) | |||||||||

| anticipatory anxiety | 3.89 | 2.79 | 0–10 | 3.74 | 2.65 | 0–10 | 3.81 | 2.70 | 0–10 |

| pain intensity | 6.02 | 2.48 | 1–10 | 5.91 | 2.31 | 2–10 | 5.96 | 2.38 | 1–10 |

| pain bother | 5.67 | 2.76 | 0–10 | 5.11 | 2.687 | 0–10 | 5.37 | 2.72 | 0–10 |

Note: JEPQ-N = Junior Eyesenck Personality Questionnaire – Neuroticism subscale; CASI = Children’s Anxiety Sensitivity Index; ASC = ascending series; MRS = multiple random staircase.

Correlation and regression analyses

Child age was significantly inversely correlated with several of the laboratory pain variables (EP MRS, r = −.23, p < .05; EP Pain Bother, r = −.21, p < .05), so this variable was controlled for in all future analyses. Partial correlational analyses controlling for child age were conducted for JEPQ-N scores, CASI scores, and Laboratory Pain variables. As shown in Table 3, both JEPQ-N and CASI scores were significantly correlated with all Laboratory Pain variables (i.e., anticipatory anxiety, pain intensity and pain bother). As expected, the Laboratory Pain variables were also highly intercorrelated, with the exception of EP ASC anticipatory anxiety and EP pain bother, which were not significantly correlated with each other.

Table 3.

Partial correlations among neuroticism, anxiety sensitivity, and lab pain variables.

| (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) JEPQ-N | .41** | .33** | .33** | .31** | .22* | .35** | .33** | .35** | .33** | .36** | .41** |

| (2) CASI | .38** | .37** | .36** | .25* | .27** | .37** | .35** | .43** | .37** | .41** | |

| Evoked Pressure (EP) | |||||||||||

| (3) anticipatory anxiety (ASC) | .75** | .31* | .17 | .62** | .47** | .32** | .74** | .45** | .37** | ||

| (4) anticipatory anxiety (MRS) | .43** | .42** | .65** | .42** | .45** | .65** | .41** | .43** | |||

| (5) pain intensity | .52** | .26** | .28** | .37** | .41** | .39** | .38** | ||||

| (6) pain bother | .26* | .24* | .34** | .22* | .25* | .27** | |||||

| Cold Pressor (CP) | |||||||||||

| (7) anticipatory anxiety | .66** | .42** | .63** | .48** | .48** | ||||||

| (8) pain intensity | .64** | .60** | .57** | .57** | |||||||

| (9) pain bother | .53** | .52** | .65** | ||||||||

| Tonic Pressure (TP) | |||||||||||

| (10) anticipatory anxiety | .67** | .55** | |||||||||

| (11) pain intensity | .78** | ||||||||||

| (12) pain bother |

Note: Correlations are controlling for child age. JEPQ-N = Junior Eyesenck Personality Questionnaire – Neuroticism subscale; CASI = Children’s Anxiety Sensitivity Index; ASC = ascending series; MRS = multiple random staircase.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Mediational model

We followed Baron and Kenny’s [3] steps to test mediational models, with Laboratory Pain variables as the dependent variables (see Figure 1). Using a series of stepwise linear regressions, we first evaluated whether JEPQ-N scores were significant predictors of each of the dependent Laboratory Pain variables (Path c). Significant models emerged for all the dependent variables. Next, we explored whether JEPQ-N scores were significant predictors of CASI scores, and this path was also significant (Path a). Finally, we evaluated whether CASI scores were significant predictors of the dependent Laboratory Pain variables, when JEPQ-N scores were included in the regression (path b), and these models were all significant except for EP pain bother and CP anticipatory anxiety.

To determine full or partial mediation, we compared the direct effect of JEPQ-N scores on Laboratory Pain variables (Path c’) with the total effect (Path c). Path c’ scores that are lower than Path c scores suggest mediation, in that inclusion of CASI scores in the model accounted for at least some, if not all, of the variance in the relationship between JEPQ-N and Laboratory Pain variables. If Path c’ coefficients still remained significant, this would suggest partial mediation, whereas if Path c’ coefficients were no longer significant, this would indicate full mediation. Full mediation by CASI scores was evident for the relationship of JEPQ-N scores and EP anticipatory anxiety (ASC), EP pain intensity, and TP anticipatory anxiety. The analyses suggested partial mediation by CASI scores for the relationships of JEPQ-N scores and EP anticipatory anxiety (MRS), CP pain intensity, CP pain bother, TP pain intensity, and TP pain bother. Significant Sobel tests confirmed each of these mediation models (see Table 4). No mediation effect emerged for the relationship of JEPQ-N scores and EP pain bother or CP anticipatory anxiety.

Table 4.

Unstandardized regression coefficients (B) and standard errors (SE) for Paths a, b, and c’ and Sobel statistics for CASI mediation of the JEPQ-N-Laboratory Pain relationship across three separate pain tasks.

| Task | Dependent Lab Pain Variable |

Path a | Path b | Path c | Path c’ | Sobel | Mediation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | ||||

| Evoked Pressure |

Anticipatory Anxiety (ASC) |

** .45 |

.10 |

** .161 |

.06 |

** .19 |

.06 | -- .12 |

.06 | 2.45* | Full |

| Anticipatory Anxiety (MRS) |

** .45 |

.10 |

* .136 |

.05 |

** .22 |

.06 |

** .16 |

.06 | 2.19* | Partial | |

| Pain Intensity |

** .45 |

.10 |

** .104 |

.04 |

** .13 |

.04 | -- .08 |

.04 | 2.23* | Full | |

| Pain Bother |

** .45 |

.10 | -- .091 |

.05 |

* .12 |

.05 | -- .08 |

.06 | 1.60 | -- | |

| Cold Pressor | Anticipatory Anxiety |

** .45 |

.10 | -- .068 |

.05 |

** .16 |

.05 |

** .13 |

.05 | 1.40 | -- |

| Pain Intensity |

** .45 |

.10 |

** .153 |

.06 |

** .20 |

.06 |

* .13 |

.06 | 2.36* | Partial | |

| Pain Bother |

** .45 |

.10 |

* .143 |

.06 |

** .22 |

.06 |

* .16 |

.07 | 2.10* | Partial | |

| Tonic Pressure |

Anticipatory Anxiety |

** .45 |

.10 |

** .195 |

.06 |

** .19 |

.06 | -- .11 |

.06 | 2.77** | Full |

| Pain Intensity |

** .45 |

.10 |

* .127 |

.05 |

** .18 |

.05 |

* .13 |

.05 | 2.27* | Partial | |

| Pain Bother |

** .45 |

.10 |

** .162 |

.05 |

** .25 |

.06 |

** .17 |

.06 | 2.49* | Partial | |

Note. Analyses were conducted controlling for child age. JEPQ-N = Junior Eyesenck Personality Questionnaire – Neuroticism subscale; CASI = Children’s Anxiety Sensitivity Index; ASC = ascending series; MRS = multiple random staircase.

p < .05,

p < .01,

-- ns/no mediation.

Discussion

We tested a mediational model which posited that neuroticism, AS, and acute pain responses would be highly correlated, with AS at least partially mediating the relationship between neuroticism and pain responses to tasks involving cold and pressure pain in a large sample of non-clinical youth. Our hypothesized model was generally supported: results demonstrated high correlations between AS, neuroticism, and laboratory pain responses for all pain tasks (see Table 3). Furthermore, AS at least partially mediated the neuroticism – laboratory pain relationship for nearly all the laboratory pain variables and these mediational models were confirmed by Sobel tests (see Table 4). However, there was no mediation effect for neuroticism and evoked pressure pain bother or cold pressor anticipatory anxiety.

Previous research has demonstrated a relationship between the higher order personality trait of neuroticism and chronic and laboratory pain in adults and adolescents [1, 2, 13, 24]; extant research has also confirmed a strong relationship between the lower order factor AS and both acute and chronic pain in both adults and children [30, 31, 33–35, 39]. However, the current results are the first, to our knowledge, to delineate the relative contribution of these higher and lower order factors to pain experience in children. The present results are consistent with our prior work linking AS and laboratory pain responses in children and adolescents [33–35], but the current data indicating that neuroticism and laboratory pain are strongly related in a sample of non-clinical youth is relatively novel. One previous study showed neuroticism predicts laboratory pain in response to the cold pressor in adults, although AS showed a stronger relationship with pain responses than neuroticism [22]. Our data extend these previous findings by demonstrating a link between neuroticism and pain responses across a variety of pain tasks involving two different pain modalities (cold and pressure pain) in a young population.

Moreover, testing mediational models allowed us to determine the relative contribution of AS (a lower order construct) to pain responses in relation to neuroticism (a higher order personality trait). We found, for the most part, AS accounts for at least part of the relationship between neuroticism and laboratory pain. Partial mediation was evident for evoked pressure multiple random staircase (MRS) anticipatory anxiety, cold pressor pain intensity and pain bother, and tonic pressure pain intensity and pain bother. Notably, full mediation of the neuroticism-laboratory pain relationship by AS was evident for evoked pressure ascending series (ASC) anticipatory anxiety, evoked pressure pain intensity, and tonic pressure anticipatory anxiety. Although these models have never been directly tested previously, our findings appear consistent with those reported by Lee and colleagues [22], who found that although neuroticism was related to pain ratings, lower-order pain constructs (such as AS, fear of pain, and pain catastrophizing) were more predictive of pain ratings and quality than higher-order traits. Another study in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis found that the neuroticism-chronic pain relationship was mediated by pain catastrophizing (also a lower-order factor), which supports the notion that neuroticism may serve as broad risk factor that, when coupled with cognitive or emotional tendencies to be fearful of pain, may contribute to higher levels of pain [2].

However, we did not find a consistent pattern of mediation across all pain ratings, as AS served as a partial mediator for some relationships, and a full mediator for other relationships. This inconsistent pattern may be due to a number of factors. First, the data may reflect that there is no clear pattern of associations among these variables in that AS and neuroticism are both correlated with pain responses, but another third variable more consistently accounts for these relationships. Another perhaps more intriguing possibility is that there are emerging (although still somewhat unclear) patterns in our data that reflect different relationships between neuroticism, AS, and aspects of acute pain responses. For example, although the data are not entirely consistent, it appears as though there may be a pattern emerging with AS fully mediating the relationship between neuroticism and anticipation of pain (anticipatory anxiety), with AS only partially mediating relationships with neuroticism and the sensory and affective aspects of pain (i.e., pain intensity and pain bother, respectively). This suggests that AS is more strongly related to anticipatory anxiety in relation to pain tasks – a notion which is supported by our previous work demonstrating a strong association between AS and anticipatory anxiety to laboratory pain [33, 35]. Although we did not measure body vigilance specifically, other research has also found a stronger relationship of AS to body vigilance as compared to neuroticism [10]. Thus, at least for anticipation of pain, neuroticism may have explanatory power only to the extent it explains variance in AS.

On the other hand, AS only partially mediated the relationship of neuroticism to pain intensity and pain bother. In this sense, neuroticism is a broad personality trait that contributes more directly to the actual sensory perception of pain as well as to its emotional or affective component [16], with AS also contributing to some degree, and these constructs together may serve to lower the threshold at which someone interprets physical sensations as dangerous [9, 31]. This idea is further supported by evidence that higher neuroticism is associated with activity in brain regions responsible for emotional and cognitive processing of pain (even though these relationships were found only during anticipation of a painful experience, rather than during the pain experience itself [6]). Our data appear to support these notions, and suggest that neuroticism may also serve as a broad vulnerability factor for pain experience in children that, when coupled with specific fears of bodily sensations, may intensify pain responses. While other factors (pain catastrophizing, etc.) may also contribute to this outcome, neuroticism can be viewed as a potentially important risk factor for the development of pain in children.

One caveat to these findings is that we did not find any relationship between pain tolerance and the other study variables (including neuroticism). This null finding may reflect the relationship of neuroticism and AS to pain variables has a stronger association with pain perception (such as anticipatory anxiety, intensity, and bother), rather than pain behavior (i.e., pain tolerance). Another possible explanation is shared method variance (i.e., use of self-report measures). Previous studies have found discordance between pain intensity and pain tolerance in laboratory studies with children [12, 32], suggesting that these response systems are influenced by different factors. In accord, task-based interventions focused on increasing tolerance have led to improvements in children’s ability to endure pain but without affecting the degree of subjective discomfort [12, 32].

Clinically, these findings suggest that if stable personality traits are less amenable to intervention without medication [9, 20] or longer-term treatment [23], it may be useful to focus treatment efforts on modifiable, lower order factors that are receptive to interventions, such as AS. Although children high in neuroticism may be more prone to develop sensitivities to pain, it may be possible to prevent the development of a pain disorder by reducing AS and, therefore, neuroticism’s influence on pain. Results from adult studies have suggested that AS is modifiable, and may address pain pathways through its reduction in pain anxiety [39]. Parents and children may prefer short-term behaviorally-based interventions to address specific factors that may be contributing to pain responses.

Several limitations to the current study should be noted. The sample population of the present study consisted of self-reported healthy children, so it is not clear whether this model would be applicable to populations with chronic physical illnesses or chronic pain. Future research should explore whether our model holds true in a variety of clinical populations. Also, all data were self-report which could introduce bias to the extent that participants were aware of and willing to report symptoms of neuroticism or AS, or were willing to report true levels of pain responses. Additionally, there may be some selection bias for study participation, as a large portion of the invited study sample declined to participate (24.5%), primarily due to lack of interest or time. This potential selection bias in the sample may limit the generalizability of the findings. Finally, although we confirmed a mediational model, this model does not imply causation as this study was cross-sectional in nature.

These data suggest that neuroticism serves as a potential risk factor for elevated pain responses [13], and can likely exacerbate pain responses when coupled with fear of bodily sensations. Although higher-order personality traits such as neuroticism may be difficult to modify without psychopharmacological treatment, our data nonetheless suggest the possibility of developing psychological interventions to address lower-order factors such as AS in children [39]. It is conceivable that reductions in AS may be associated with diminished acute pain responses, especially among children who score highly on neuroticism measures, although this is only speculative given that we did not evaluate the impact of modifying AS in the current study. Also, our data suggest that the assessment of both neuroticism and AS when evaluating children with pain problems may assist in tailoring appropriate interventions.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (5F32MH084424; PI: Laura B. Allen), a grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (5R01DE012754; PI: Lonnie K. Zeltzer), and UCLA Clinical and Translational Research Center CTSI Grant UL1RR033176 (PI: Lonnie K. Zeltzer).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Aaseth K, Grande RB, Leiknes KA, Benth JS, Lundqvist C, Russell MB. Personality traits and psychological distress in persons with chronic tension-type headache. The Akershus study of chronic headache. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124:375–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Affleck G, Tennen H, Urrows S, Higgins P. Neuroticism and the pain-mood relation in rheumatoid arthritis: insights from a prospective daily study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:119–126. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnie KA, Petter M, Boerner KE, Noel M, Chambers CT. Contemporary Use of the Cold Pressor Task in Pediatric Pain Research: A Systematic Review of Methods. J Pain. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.06.005. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caruso JC, Edwards S. Reliability generalization of the Junior Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;31:173–184. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coen SJ, Kano M, Farmer AD, Kumari V, Giampietro V, Brammer M, Williams SC, Aziz Q. Neuroticism influences brain activity during the experience of visceral pain. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:909–917. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.008. e901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Four ways five factors are basic. Pers Individ Dif. 1992;13:653–665. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dufton LM, Konik B, Colletti R, Stanger C, Boyer M, Morrow S, Compas BE. Effects of stress on pain threshold and tolerance in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Pain. 2008;136:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekselius L, Von Knorring L. Changes in personality traits during treatment with sertraline or citalopram. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:444–448. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esteve MR, Camacho L. Anxiety sensitivity, body vigilance and fear of pain. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:715–727. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Scales. London: Hodder and Stoughton; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fanurik D, Zeltzer LK, Roberts MC, Blount RL. The relationship between children's coping styles and psychological interventions for cold pressor pain. Pain. 1993;53:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goubert L, Crombez G, Van Damme S. The role of neuroticism, pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in vigilance to pain: a structural equations approach. Pain. 2004;107:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gracely RH, Grant MA, Giesecke T. Evoked pain measures in fibromyalgia. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:593–609. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6942(03)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gracely RH, Lota L, Walter DJ, Dubner R. A multiple random staircase method of psychophysical pain assessment. Pain. 1988;32:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harkins SW, Price DD, Braith J. Effects of extraversion and neuroticism on experimental pain, clinical pain, and illness behavior. Pain. 1989;36:209–218. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazlett-Stevens H, Craske MG, Mayer EA, Chang L, Naliboff BD. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome among university students: the roles of worry, neuroticism, anxiety sensitivity and visceral anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:501–505. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(03)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones A, Zachariae R. Investigation of the interactive effects of gender and psychological factors on pain response. Br J Health Psychol. 2004;9:405–418. doi: 10.1348/1359107041557101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keough ME, Schmidt NB. Refinement of a Brief Anxiety Sensitivity Reduction Intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0027961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knutson B, Wolkowitz OM, Cole SW, Chan T, Moore EA, Johnson RC, Terpstra J, Turner RA, Reus VI. Selective alteration of personality and social behavior by serotonergic intervention. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:373–379. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009;64:241–256. doi: 10.1037/a0015309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JE, Watson D, Frey Law LA. Lower-order pain-related constructs are more predictive of cold pressor pain ratings than higher-order personality traits. J Pain. 2010;11:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leichsenring F, Leibing E. The effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of personality disorders: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1223–1232. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merlijn VP, Hunfeld JA, van der Wouden JC, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, Koes BW, Passchier J. Psychosocial factors associated with chronic pain in adolescents. Pain. 2003;101:33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mounce C, Keogh E, Eccleston C. A principal components analysis of negative affect-related constructs relevant to pain: evidence for a three component structure. J Pain. 2010;11:710–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saklofske DH, Eysenck SB. A comparison of responses of Canadian and English Children on the Junior Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Canad J Behav Sci. 1983;15:121–130. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverman WK, Fleisig W, Rabian B, Peterson RA. Child Anxiety Sensitivity Index. J Clin Child Psychol. 1991;20:162–168. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith TW, MacKenzie J. Personality and risk of physical illness. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:435–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam J, Shelton R, Schalet B. Personality change during depression treatment: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1322–1330. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsao JC, Allen LB, Evans S, Lu Q, Myers CD, Zeltzer LK. Anxiety sensitivity and catastrophizing: associations with pain and somatization in non-clinical children. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:1085–1094. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsao JC, Evans S, Meldrum M, Zeltzer LK. Sex differences in anxiety sensitivity among children with chronic pain and non-clinical children. J Pain Manag. 2009;2:151–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsao JC, Fanurik D, Zeltzer LK. Long-term effects of a brief distraction intervention on children's laboratory pain reactivity. Behav Modif. 2003;27:217–232. doi: 10.1177/0145445503251583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsao JC, Lu Q, Kim SC, Zeltzer LK. Relationships among anxious symptomatology, anxiety sensitivity and laboratory pain responsivity in children. Cogn Behav Ther. 2006;35:207–215. doi: 10.1080/16506070600898272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsao JC, Lu Q, Myers CD, Kim SC, Turk N, Zeltzer LK. Parent and child anxiety sensitivity: relationship to children's experimental pain responsivity. J Pain. 2006;7:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsao JC, Myers CD, Craske MG, Bursch B, Kim SC, Zeltzer LK. Role of anticipatory anxiety and anxiety sensitivity in children's and adolescents' laboratory pain responses. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29:379–388. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vervoort T, Goubert L, Eccleston C, Bijttebier P, Crombez G. Catastrophic thinking about pain is independently associated with pain severity, disability, and somatic complaints in school children and children with chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:674–683. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Baeyer CL, Piira T, Chambers CT, Trapanotto M, Zeltzer LK. Guidelines for the cold pressor task as an experimental pain stimulus for use with children. J Pain. 2005;6:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.01.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Baeyer CL, Spagrud LJ, McCormick JC, Choo E, Neville K, Connelly MA. Three new datasets supporting use of the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS-11) for children's self-reports of pain intensity. Pain. 2009;143:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watt MC, Stewart SH, Lefaivre MJ, Uman LS. A brief cognitive-behavioral approach to reducing anxiety sensitivity decreases pain-related anxiety. Cogn Behav Ther. 2006;35:248–256. doi: 10.1080/16506070600898553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weems CF, Hammond-Laurence K, Silverman WK, Ginsburg GS. Testing the utility of the anxiety sensitivity construct in children and adolescents referred for anxiety disorders. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998;27:69–77. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2701_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]