A patient-reported outcome (PRO) can be defined as “any report of the status of a patient's health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient's response by a clinician or anyone else”.1 The study reported by Deschler et al.2 in this issue of the Journal further confirms that patients themselves can provide important prognostic data for survival. Importantly, their findings echoed the results obtained from the literature on solid tumors regarding the prognostic value of PROs. Arguing against the often widespread belief that PROs might provide only limited information to guide decision-making in the clinical setting, the study by Deschler et al.2 points out that what patients tell us about how they feel provides unique prognostic information

PROs have been found to independently predict duration of survival in several advanced cancer disease sites.3 Nevertheless, there has been little research documenting the association between PROs and survival in patients with hematologic diseases, and Deschler and colleagues2 should be applauded for this initiative. While the reasons underlying the correlation between PROs and survival outcomes are not yet fully understood, it is possible to speculate that, at the very least, PRO data capture the full breadth of the underlying disease severity in a different way to traditional laboratory or clinical examinations.4

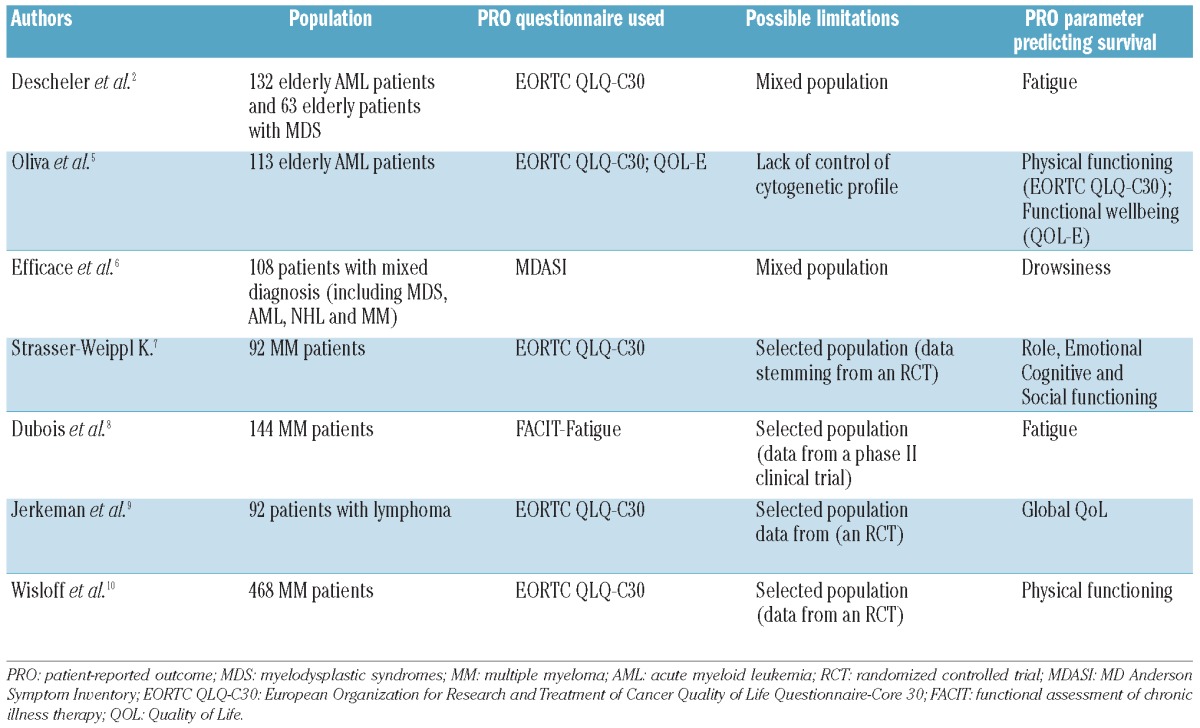

To illustrate these concepts, Table 1 shows a non-systematic summary of findings of studies into prognostic factors in hematologic diseases that have also considered PROs. Despite their heterogeneity, overall these study results challenge the scientific community with a series of questions concerning the potential clinical implications.

Table 1.

Overview of prognostic factor studies and patient-reported outcomes in patients with hematologic diseases.

Using a series of geriatric and Quality of Life (QoL) assessment tools, Deschler et al.2 show that baseline (i.e. pre-treatment) patients' self-reports of fatigue severity, measured with the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire, is an independent predictor of survival in a series of 195 elderly patients. Their cohort was made up of 63 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) with mixed or unknown IPSS risk categories and 132 patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). One of the strengths of this study consists in controlling for key previously known disease-related risk factors for these cancer populations, i.e. cytogenetic and bone marrow blast data. Also, comorbidity was assessed with robust previously validated indices.

How can we translate the findings of the study of Deschler et al.2 into information useful for our clinical practice? Is it possible to envisage that patients' ratings of fatigue severity will routinely be used, along with cytogenetic or bone marrow blast data (or even replacing them) to obtain a more meaningful judgment of the patient's prognostic profile? Is current evidence-based data sufficient to fully support such an approach?

Prognostic factor analyses (PFA) in cancer research have traditionally focused on patient socio-demographic characteristics, and clinical and laboratory data. Only over the last decade, we have seen a growing number of PFAs that also included PROs. The use of PROs in traditional prognostic factor analyses, however, has introduced specific methodological challenges which have frequently hindered a critical appraisal of results.11 For example, while “multicollinearity” is a known challenge in traditional PFA, it becomes even more problematic when PROs are included.12 Multicollinearity occurs when two or more predictor variables are highly correlated (which is often the case for PROs) thus leading to incorrect model selection and, in any case, making it difficult to disentangle the real influence of each single predictor variable.11,12

While there is still no gold standard to address this issue, some statistical techniques have been developed to further test the stability of the final multivariate predictive model and to obtain insight into the real value of a single factor being an independent prognostic variable. In the context of QoL studies, Van Steen et al.12 have extensively illustrated a bootstrap model averaging technique which was later successfully used in several methodologically sound studies of patients with solid tumors.13,14 Also, a crucial aspect that could be considered is the importance of an a priori selection of specific PRO scales to be included in the analyses. PRO instruments typically consist of several scales measuring different aspects of a patient's health status (e.g. functional, social, psychological functions and various symptom domains) that should not necessarily be all entered in the Cox's regression analysis. For example, one of the most frequently used QoL instruments in these studies, the EORTC QLQ-C30, yields 15 different scales. Since too high a number of variables could increase the risk of selecting a factor only by chance, an a priori and thoughtful selection of key PRO scales (relevant for the particular cancer population being studied) should always be recommended.

Another challenge, commonly seen in PFA, is the inadequate statistical control of previously known biomedical prognostic factors and the lack of validation of findings in independent datasets.

Interestingly, two papers recently published in this Journal exemplify this complex scenario and show how challenging it is to draw conclusions from such studies. The Deschler et al. study2 included patients with AML, as did the other study by Oliva et al.,5 and both investigated the prognostic value of PROs at baseline in the same cancer population. Both studies included patients with AML over 60 years of age and used, among other instruments, the same PRO measure (i.e. the EORTC QLQ-C30). However, while Deschler et al.2 found “fatigue” to be an independent predictor of survival, Oliva et al.5 found “physical functioning” to be so (both scales stemming from the EORTC QLQ-C30). In the study of Oliva et al.,5 however, the analysis did not control for a key previously known prognostic factor for AML patients (i.e. cytogenetics) thus significantly limiting the possibility of drawing conclusions about the actual independent prognostic value of PROs. In the study of Deschler et al.,2 the concomitant inclusion of patients with MDS in the analysis might have influenced outcomes. To what extent, therefore, can we trust that using patients' self-reports will help clinicians in a more accurate prognostic assessment of AML patients?

While both studies have provided some new insights into this neglected area of research in hematology, we conclude that much still has to be done to translate current research findings into clinically meaningful information. While we are confident that this important line of research will eventually promote a more accurate prognostic assessment, today it is still difficult to envisage the way patient-reported health status information can be implemented into future routine prognostic evaluation. In any case, these studies do underscore the importance of routine collection of PRO data in patients with AML and MDS. PRO instruments are starting to be incorporated into the standard diagnostic workup in individual patients and the information derived from this will make it easier for us to make accurate prognoses. However, in hematology, this approach is still in its infancy, and the evidence available so far should only be considered in terms of work in progress. Future hypothesis-driven prospective studies conducted in homogenous patient cohorts, careful attention to methodological issues associated with these analyses, and validation of findings in independent datasets will all definitely help move science forward in this area.

Footnotes

Financial and other disclosures provided by the author using the ICMJE (www.icmje.org) Uniform Format for Disclosure of Competing Interests are available with the full text of this paper at www.haematologica.org.

References

- 1.US Food and Drug Administration: Guidance for Industry Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. US: Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration; December, 2009. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deschler B, Ihorst G, Platzbecker U, Germing U, Marz E, de Figuerido M, et al. Parameters detected by geriatric and quality of life assessment in 195 older patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia are highly predictive for outcome. Haematologica. 2012. August 8; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotay CC, Kawamoto CT, Bottomley A, Efficace F. The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1355–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Efficace F, Innominato PF, Bjarnason G, Coens C, Humblet Y, Tumolo S, et al. Validation of patient's self-reported social functioning as an independent prognostic factor for survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: results of an international study by the Chronotherapy Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer.J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(12):2020–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliva EN, Nobile F, Alimena G, Ronco F, Specchia G, Impera S, et al. Quality of life in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: patients may be more accurate than physicians. Haematologica. 2011;96(5):696–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Efficace F, Cartoni C, Niscola P, Tendas A, Meloni E, Scaramucci L, et al. Predicting survival in advanced hematologic malignancies: do patient-reported symptoms matter? Eur J Haematol. 2012;89(5):410–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strasser-Weippl K, Ludwig H. Psychosocial QOL is an independent predictor of overall survival in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol. 2008;81(5):374–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubois D, Dhawan R, van de Velde H, Esseltine D, Gupta S, Viala M, et al. Descriptive and prognostic value of patient-reported outcomes: the bortezomib experience in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):976–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jerkeman M, Kaasa S, Hjermstad M, Kvaløy S, Cavallin-Stahl E. Health-related quality of life and its potential prognostic implications in patients with aggressive lymphoma: a Nordic Lymphoma Group Trial.Med Oncol. 2001;18(1):85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wisløff F, Hjorth M. Health-related quality of life assessed before and during chemotherapy predicts for survival in multiple myeloma. Nordic Myeloma Study Group. Br J Haematol. 1997;97(1):29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauer M, Bottomley A, Coens C, Gotay C. Prognostic factor analysis of health-related quality of life data in cancer: a statistical methodological evaluation. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8(2):179–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Steen K, Curran D, Kramer J, Molenberghs G, Van Vreckem A, Bottomley A, et al. Multicollinearity in prognostic factor analyses using the EORTC QLQ-C30: identification and impact on model selection. Stat Med. 2002;21(24):3865–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bottomley A, Coens C, Efficace F, Gaafar R, Manegold C, Burgers S, et al. Symptoms and patient-reported well-being: do they predict survival in malignant pleural mesothelioma? A prognostic factor analysis of EORTC-NCIC 08983: randomized phase III study of cisplatin with or without raltitrexed in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5770–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Efficace F, Bottomley A, Smit EF, Lianes P, Legrand C, Debruyne C, et al. Is a patient's self-reported health-related quality of life a prognostic factor for survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients? A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of EORTC study 08975. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(11):1698–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]