Abstract

This clinical case report shows how important it is for a psychiatrist to have a knowledge of the cultural and religious context of the patient, in order to understand fully his or her complaints. Culture and religion, in fact, are not neutral, but convey symbols, meanings, and myths that should be properly explored to shed light on the patient’s inner world. Patient D was a 19-year-old Muslim Italo-Tunisian girl, who consulted a psychiatrist for anxiety and panic attacks, and reported being possessed by djinns (ie, “evil creatures”, as described in the Qur’an). A culturally informed interview was carried out, together with administration of psychometric scales, including the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised and Psychological Measure of Islamic Religiousness. Based on her scores and the results of this multidimensional assessment, patient D was treated with transcultural psychotherapy and fluoxetine. After a year of follow-up, she reported no further episodes of panic disorder. For proper assessment and treatment, a combined anthropological, sociological, and psychopathological approach was necessary.

Keywords: Islam, Qur’an, djinns, panic attack disorder, ethnopsychiatry

Introduction

“The Prophet said: ‘Cover your utensils and tie your water skins, and close your doors and keep your children close to you at night as the djinn spread out at such time and snatch things away.’” (Sahih al-Bakhari 4.533). Migration is a well known stress-inducing phenomenon,1,2 because it is not just a single event but a highly complex chain of events unraveling throughout different stages (from premigration, displacement, and post-migration to the acculturation phases),3 and thus implying a need for adaptation skills, coping behaviors, resilience, adjustment strategies, self-esteem, and motivation.4 Migration challenges the very concepts of self and identity,5 and migrant psychological profile, personality, and vulnerability,6 as well as social factors (like the existence of social networks, social cohesion, and peer support) are predictors of the health outcome.7 Several empirical studies have shown that immigrants are likely to suffer from psychological problems and psychiatric disorders, such as depression and somatoform diseases, at higher rates than the indigenous.2 For these reasons, migrant mental health is an extremely important topic, especially for ethnopsychiatry and liaison/consultation psychiatry.

While Afro-American, Caribbean, Latinos, and Asian immigrants have been extensively investigated, Muslim migration has only recently attracted attention because of its historical and actual urgency. Muslim migrants are a particular class of immigrants, being a highly heterogeneous and vulnerable population, characterized by peculiar and unique stressor factors linked with their religious and cultural identity.8,9 In recent years, scholars have reported an increase in Muslims seeking mental health services and care after “the 9/11 era”, because of rising discrimination, prejudices, social stigma, and negative attitudes towards them. Little and/or contradictory knowledge of Arabic and Muslim worlds may contribute to the formation of biased opinions, so culturally informed transcultural psychotherapy is advocated as being mandatory.10

Djinn possession in migrants is a topic which so far has been scarcely considered by ethnopsychiatry, despite its interest and importance. Here we describe a clinical case of a Muslim girl reporting possession by djinns and panic attacks. We discuss this case in depth, providing the cultural framework for an appropriate psychological treatment.

Case report

Subject history

A 19-year-old Muslim Italo-Tunisian girl, referred to here as patient D, attended the outpatient facility of our psychiatric service for diagnosis and treatment of anxiety and panic disorder, and came to our attention for reporting a feeling that djinns were invading her body and her mind, and she was afraid of going mad. She also complained of psychosomatic malaise, feeling depressed, and bursting into tears suddenly without any apparent reason.

Even though the onset of the panic attacks had its root in the last year of high school, she accessed us late, after consulting traditional healers (amal or fqih) without success and following the suggestion of her cousins living in Tunisia to use taweez, tamima, shirk, and nashra (amulets and lucky charms).11

Patient D was born in Tunisia and grown up in Italy, was perfectly bilingual (fluently speaking Italian and Arabic, both classical and vernacular), and apparently integrated into the Italian community. Even though born in Tunisia, she had little memory of her early years spent there until the age of 9 years, when she moved to Italy together with her family. Since then she had rarely visited Tunisia.

When asked about her relationship with her family, she described her father as an absent, mostly shy, and marginal figure in her development. She remembered frequent discussions between her father and her mother during her infant years. She identified with her mother, reporting that she wanted to protect her mother from an evil father-husband. Her mother was her ideal role model, but she did not want to repeat her mother’s mistakes, like being too influenced by men, about whom she had ongoing reservations and diffidence. She defined this as a cultural Arabic heritage of which she wanted to be rid.

Earlier that year she decided to move again with her mother to continue studying and working in Tunisia, but she felt upset and disappointed to find the country completely different from her expectations, probably because she had idealized it so much. She said it was not the appealing country she had dreamed of, and women there were living as if in the Middle Ages. She had always refused to wear the veil (hijab). Sometimes she thought that Islam was an unfair religion that could make people become intolerant. When asked if she would define herself as a Muslimah (Muslim girl), she could not reply with certainty. She was aware of her contradictions, because she was fascinated by Islam but at the same time was repelled by it. Islam pervaded her sentences (“Islam is like a flavor, a spice, a color”, she repeated) but not always her actions (sometimes she forgot to pray and afterwards she felt very bad about this). Islam for her was a constantly absent presence.

She was worried for her professional future, suffering from lack of money. For this reason, she was looking for a job in order to help her mother and to support herself while attending university. She felt that there were big challenges ahead and so was sometimes elated and excited and sometimes frustrated. Her mood was highly variable and strongly situation-dependent.

In her last year of high school and during her temporary residence in Tunisia she suffered from panic attacks. She reported seeing djinns, while things around her became abruptly strange and unfamiliar. During her visions and possession by djinns, she avoided dark rooms and haram situations to be less vulnerable to their attacks. When she saw a djinn, she immediately took the Qur’an and read and prayed, worried by the idea that djinns could enter her brain. “Maybe all this happens because Allah is punishing me for not being a real Muslimah”, she wondered. She reported that her mother and grandparents had also suffered from possession by djinns.

Measures and psychometric apparatus

Religiosity is a complex multidimensional aspect of a person’s life, which has a controversial relationship with psychopathology.12,13 Some studies have shown how a certain level of religiosity enables the subject to be more resilient and resistant to outer stressors, while others have observed connections between religiosity and neuroticism, as well as other psychiatric conditions. Either way, it must be underlined that religiosity is an umbrella for an array of beliefs, emotions, and practices that stem from the parents’ backgrounds and influences, producing a unique combination of external (familiar and societal) pressure and internal autonomy, zeal, and commitment. Religion can be a strategy of coping but also a source of distress. It is a very delicate theme to investigate, but is also of crucial importance in the psychological assessment.

There are different psychometric scales for measuring religious attitudes, but the PMIR (Psychological Measure of Islamic Religiousness scale)14 was used here because it is the first and unique psychometric scale for specific measurement of Muslim religiosity. This questionnaire was complemented with the SCL-90-R (Symptoms Check-List 90 Revised).15 This is a 90-item self-report questionnaire developed by Leonard Derogatis in the 1970s for measurement of psychological symptoms and psychological distress. It was designed to be suitable for use with individuals in the community, as well as individuals with either medical or psychiatric conditions. The SCL-90-R uses nine primary symptom dimensions and a summary score termed the Global Severity Index. The SCL-90-R was chosen because of its high internal consistency and also because it has already been proven to be reliable when administered to migrants in association with a questionnaire related to religiosity and other cultural variables.16,17

Results

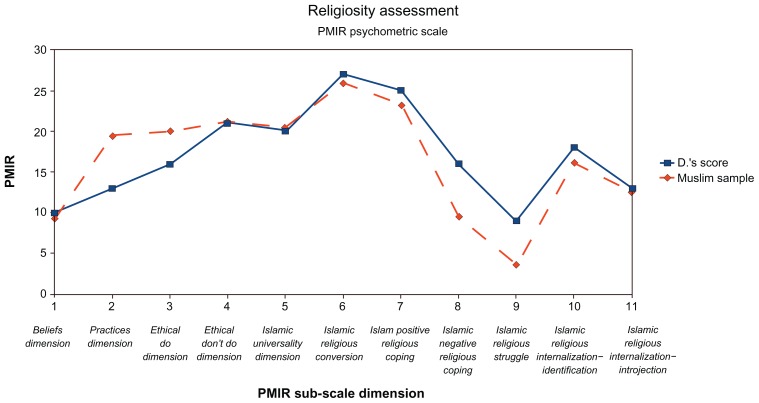

The patient’s PMIR scores are reported in Figure 2 and compared with mean scores obtained in a Muslim sample, and show an altered profile for the following traits: practices dimension, ethical-conduct do dimension, Islamic negative religious coping, and Islamic religious struggle subscales. This finding confirms that patient D used her Islamic religion in a different way from the average Muslim and had a conflicted attitude towards her own faith.

Figure 2.

Scores obtained by patient D for each subscale dimension of the Psychological Measure of Islamic Religiousness compared with mean scores for a Muslim sample.

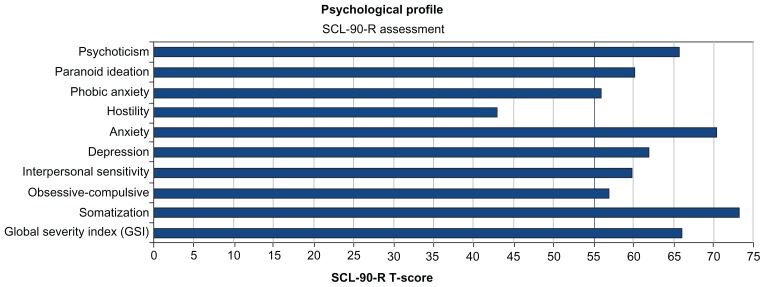

SCL-90-R scores are reported in Figure 1. As can be seen, considering that the normality cutoff value is 55%, all subscales are above this range (apart from the hostility dimension), with anxiety and somatic symptoms as a prominent part of patient D’s clinical presentation. The differential diagnosis was challenging and not trivial, given that patient D also showed symptoms of other disorders, including psychosis, dissociative pathology, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression. However, adoption of a transcultural perspective as well as analysis of the cultural context allowed us to rule them out and to focus on a diagnosis of panic attack disorder.

Figure 1.

The psychological profile of patient D obtained from the Symptom Checklist 90 Revised psychometric scale.

Notes: The vertical blue line indicates the normality cutoff value. All subscale scores are altered apart from the hostility dimension.

In fact, in Muslim countries, madness (majnoun, literally “djinn possession”)18–22 is usually explained using extrinsic models, ie, models in which the cause of the disease is an outer event/element and beyond one’s control. In other words, using the model of the health locus of control, we would say that most Muslims have an external locus of control orientation. One of the models used to explain madness is the djinn model, which we will investigate further in the Discussion section of this paper.

Treatment

Because of the complex multidimensional aspects presenting in this clinical case, treatment was focused on the individual sphere and the sociocultural dimension (Italo-Tunisian culture, djinn possession, religiosity, family relationships, and interactions) based on patient D’s scores of the psychometric scales. Our work required the presence of an ulama (a Muslim read man), who helped patient D with the difficult process of rediscovering her religion and her roots, asking and listening to her doubts, and guiding her in the process of acquiring a more positive attitude towards her faith. We term this process “religious restructuring and reframing”.

Psychological counseling and psychotherapy were complemented by neuropsychopharmacological treatment. Fluoxetine, an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor class, was prescribed according to a standard dosing schedule for panic attacks at a dose of 10 mg/day for a week and later increased up to 20 mg daily. The therapy did not cause any adverse effects, and the patient stated she was willing to continue treatment with the drug because she had noticed a significant improvement and subjective symptom relief. By the end of the fourth week, a decrease in symptoms was observed. Fluoxetine and transcultural counseling helped patient D to recover quite well from her anxiety and panic attacks. After a year of follow-up, she reported no further panic attacks.

Discussion

We consider that cultural frameworks cannot be ignored when arriving at a proper nosological diagnosis and when undertaking appropriate psychological treatment The starting observation is the view that djinns as a cause of madness, as mentioned in the Qur’an, is an erroneous belief, which is surprisingly widespread, even among the scholars. The key point to bear in mind is what a djinn really is, ie, a creature principally mentioned in the 15th chapter of the Holy Book (verses 26 and 27): “And We did certainly create man out of clay from an altered black mud. And the djinn We created before from scorching fire.”

Other chapters of the Qur’an also describe the properties of djinns, which are quoted 33 times and never linked (either directly or indirectly) to mental health or disease, as wrongly reported in the literature and correctly claimed only by Islam and Campbell.23

Another point to emphasize is that the patient reported being able to see the djinns, while the chapter “The Heights” (verse 27) openly denies this possibility: “O children of Adam, let not Satan tempt you as he removed your parents from Paradise, stripping them of their clothing to show them their private parts. Indeed, he sees you, he and his tribe, from where you do not see them. Indeed, We have made the devils allies to those who do not believe.”

This allows us to speak further of “religious camouflage”.24–26 Djinn in this context is not an exegetic entity but a myth, and something emerging from patient D’s past and haunting her. For this reason, in order to see quantitatively how patient D “used” religion, we used an ad hoc psychometric scale interview.

Cultural camouflage and ethnocultural ambiguity can cause a patient’s identity to become caught up in many contradictions. The psychiatrist should be able to capture all the metaphors and the cultural processes, such as those belonging to the trauma agenda and the djinn possession states that exert their influence on a patient’s mental health. This is especially true when we are talking about “in-between” people, in which religions and cultures confound themselves, hybridizing the boundaries and sometimes creating identity problems.27–29

Conclusion

This case study shows how important it is for a psychiatrist to have a knowledge of the religious context and culture of the patient to understand his or her complaints fully. Culture and religion are not neutral, but convey symbols and myths that should be properly explored to shed light on the patient’s inner world.

Many different agendas have to be taken into account when assessing the patient’s mental health, and within the framework of transcultural counseling, from the cultural, religious, emotional, and psychodynamic points of view. These agendas are often interwoven, so a complex multidimensional approach is needed. It is well accepted that religion plays an important role in well-being and mental health, but it is not a static reality. It is indeed complex, multifaceted, and dynamic. The individual summons up an array of narratives and myths and embraces them, making them personal, giving them his or her own meaning. Religious metaphors and (sometimes erroneous) beliefs were widely disseminated in patient D’s narratives and symptom agendas, ie, her conflicted and controversial relationship with religion mixed with her difficult parental relationship. For these reasons, to ensure proper assessment and treatment, a combined anthropological, sociological, and psychopathological approach was necessary.

Acknowledgment

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and/or any accompanying images. Human subject approval was obtained from our psychiatry department.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

- 1.Al-Issa I. Ethnicity, immigration, and psychopathology. In: Al-Issa I, Tousignant M, editors. Ethnicity, Immigration, and Psychopathology. New York, NY: Plenum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhugra D. Migration and mental health. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:243–258. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Froschauer K. East Asian and European entrepreneur immigrants in British Columbia, Canada: post-migration conduct and pre-migration context. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2001;27:225–240. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan D, Dooley B, Benson C. Theoretical perspectives on post-migration adaptation and psychological well-being among refugees: towards a resource-based model. J Refug Stud. 2008;21:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akhtar S. A third individuation: immigration, identity and the psychoanalytic process. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1994;4:1051–1085. doi: 10.1177/000306519504300406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boneva BS, Frieze IH. Toward a concept of a migrant personality. J Soc Issues. 2001;57:477–491. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Searle W, Ward C. The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. Int J Intercult Relat. 1990;14:449–464. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaleby K. Psychotherapy with Arab patients: towards a culturally oriented technique. Arab J Psychiatry. 1992;3:16–27. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caroppo E, Muscelli C, Brogna P, Paci M, Camerino C, Bria P. Relating with migrants: ethnopsychiatry and psychotherapy. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2009;45:331–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aloud N, Rathur A. Factors affecting attitudes toward seeking and using formal mental health and psychological services among Arab Muslim populations. Journal of Muslim Mental Health. 2009;4:79–103. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al Subaie A. Traditional healing experiences in patients attending a university outpatient clinic. Arab J Psychiatry. 1994;5:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witztum E, Grisaru N, Dudowski D. Mental illness and religious change. BMJ. 1990;63:33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1990.tb02854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peteet JR, Lu FG, Narrow WE, editors. American Psychiatric Association. Narrow Religious and Spiritual Issues in Psychiatric Diagnosis: A Research Agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abu Raya H. A psychological measure of Islamic religiousness: evidence for relevance, reliability and validity. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2012;41:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derogatis LR, Savitz KL. The SCL-90-R and the brief symptom inventory (BSI) in primary care. In: Maruish ME, editor. Handbook of Psychological Assessment in Primary Care Settings. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bragazzi NL, Del Puente G. Musical Attitudes and Correlations with Mental Health in a Sample of Musicians, Non-Musicians and Immigrants: A Pilot Study Implications for Music Therapy. Open Access Scientific Reports. 2012;1:366. doi: 10.4172/scientificreports.366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawood AA. Thesis. California State University; 2010. Relationship between Mental Health and Treatment Seeking in an Urban Muslim Community. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Issa I. Mental Illness in the Islamic World. Madison, CT: International Universities Press Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dols MW. Majnun: The Madman in Medieval Islamic Society. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guiley RE, Imbrogno PJ. The Vengeful Djinn: Unveiling the Hidden Agenda of Genies. Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Worldwide; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzder J. Fourteen djinns migrate across the ocean. In: Drozdek B, Wilson JP, editors. Voices of Trauma: Treating Psychological Trauma Across Cultures. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qadri AA. Jinn, magic or mental illness? (In the light of the Holy Qur’an and Hadith) [Accessed November 28, 2012]. Available from: http://www.mentalhealthcenterindia.org/pdf/Jinn%20Jadu%20english.pdf.

- 23.Islam F, Campbell RA. “Satan has afflicted me!” Jinn-possession and mental illness in the Qur’an. J Relig Health. 2012 Jul 12; doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9626-5. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giordano J. Mental health and the melting pot: an introduction. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1994;64:342–345. doi: 10.1037/h0085050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vautier M. Religion, postcolonial side-by-sidedness, and transculture. In: Moss L, editor. Is Canada Postcolonial? Waterloo, ON: W Lauriel UP; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bibeau G. Cultural psychiatry in a creolizing world: questions for a new research agenda. Transcult Psychiatry. 1997;34:9–41. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrett JR, Roediger D. Inbetween peoples: race, nationality and the “new immigrant” working class. J Am Ethn Hist. 1997;16:3–44. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orsi R. The religious boundaries of an inbetween people: Street feste and the problem of the dark-skinned other in Italian Harlem, 1920–1990. Am Q. 1992;44:313–347. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh-Schellhorn M. ASNEL Papers 3. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Rodope; 1994. Transcultural Intertextuality and the White Creole woman. Across the Lines. [Google Scholar]