Abstract

Objectives

Gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) is a rare disease that is often diagnosed incidentally in its early stages. Simple cholecystectomy is considered the standard treatment for stage I GBC. This study was conducted in a large cohort of patients with stage I GBC to test the hypothesis that the extent of surgery affects survival.

Methods

The National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database was queried to identify patients in whom microscopically confirmed, localized (stage I) GBC was diagnosed between 1988 and 2008. Surgical treatment was categorized as cholecystectomy alone, cholecystectomy with lymph node dissection (C + LN) or radical cholecystectomy (RC). Age, gender, race, ethnicity, T1 sub-stage [T1a, T1b, T1NOS (T1 not otherwise specified)], radiation treatment, extent of surgery, cause of death and survival were assessed by log-rank and Cox's regression analyses.

Results

Of 2788 patients with localized GBC, 1115 (40.0%) had pathologically confirmed T1a, T1b or T1NOS cancer. At a median follow-up of 22 months, 288 (25.8%) had died of GBC. Five-year survival rates associated with cholecystectomy, C + LN and RC were 50%, 70% and 79%, respectively (P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that surgical treatment and younger age were predictive of improved disease-specific survival (P < 0.001), whereas radiation therapy portended worse survival (P = 0.013).

Conclusions

In the largest series of patients with stage I GBC to be reported, survival was significantly impacted by the extent of surgery (LN dissection and RC). Cholecystectomy alone is inadequate in stage I GBC and its use as standard treatment should be reconsidered.

Introduction

An estimated 9810 new cases of gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) were diagnosed in the USA in 2011, resulting in 3200 deaths.1 Outcomes in patients with regional GBC improve after the resection of liver segments IVb and V and the dissection of periportal lymph nodes (LNs).2–6 This approach has been recommended for patients with tumour extending into the liver (tumour stage T2 or higher).2–5 By contrast, GBC confined to the lamina propria (T1a) or to the muscularis propria (T1b) has historically been treated with cholecystectomy alone and very small studies have reported good results.7,8 Most patients with localized GBC are diagnosed incidentally after routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy.2,9,10 Despite evidence for the adverse prognostic impact of LN metastases, the need for further surgery in these patients remains controversial.5,11–15

Current staging of GBC follows the standard tumour–node–metastasis (TNM) system (Table 1) and reflects progressively worse survival with increasing stage.16 This study reports the largest population-based analysis of outcomes of stage I GBC patients in the USA by demographic, treatment and survival characteristics. This study was conducted to test the hypothesis that patients in whom surgical treatment included LN dissection or radical cholecystectomy (RC) would survive longer than patients treated with cholecystectomy alone.

Table 1.

American Joint Committee on Cancer staging for gallbladder cancer16

| Stage | TNM | Depth | Regional lymph node status | Distant metastases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | In situ | None | None |

| Ia | T1aN0M0 | <Lamina propria | None | None |

| Ib | T1bN0M0 | <Muscular layer | None | None |

| II | T2N0M0 | <Perimuscular tissue; no extension beyond serosa or into liver | None | None |

| IIIa | T3N0M0 | >Serosa and/or directly invades the liver and/or other adjacent organ or structure | None | None |

| IIIb | T1-3N1M0 | Any | Positive nodes along cystic duct bile, common bile duct, hepatic artery and/or portal vein | None |

| IVa | T4N0M0 | Invades main portal vein, hepatic artery or >2 extrahepatic organs/structures | None | None |

| T2N1M0 | < Perimuscular tissue; no extension beyond serosa or into liver | Positive nodes along cystic duct bile, common bile duct, hepatic artery and/or portal vein | None | |

| IVb | T1-3N2M0 | Any | Positive nodes: peri-aortic, pericaval, superior mesenteric artery and/or coeliac artery lymph nodes | None |

| T1-3N1-2 M1 | Any | Any | Yes | |

TNM, tumour–node–metastasis; Tis, tumour in situ.

Materials and methods

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry is a government-run database that collects population-based data from 14 regional and three supplemental cancer registries, which together represent approximately 26% of the population in the USA.17 Data held in the SEER registry contain no identifiers and are publicly available for studies of cancer-based epidemiology and health policy, and thus are exempt from institutional review board approval requirements. The NCI's SEER*Stat software was used to identify patients in whom microscopically confirmed, invasive, localized, node-negative GBC was diagnosed between 1988 and 2008.18 A 98% case ascertainment is mandated with annual quality assurance studies.17 Only patients with stage I [T1a, T1b, T1NOS (not otherwise specified)] GBC were included. Patients were excluded if they had in situ or T2 or worse disease as determined by the extent of disease codes. Patients were also excluded if surgical treatment included locally ablative treatment, biopsy only or surgery not otherwise specified. Age, sex, race, ethnicity, T1 sub-stage, tumour grade, tumour histology, radiation treatment, extent of surgery, cause of death, survival in months and vital status were assessed. Chemotherapy data are not included in the SEER database.

Surgical treatment in the SEER database is categorized as comprising: simple cholecystectomy with no LNs recovered per extent of disease coding; cholecystectomy with any LN recovery reported in the extent of disease coding (C + LN); RC including any type of liver resection with extensive LN dissection, and surgery not otherwise specified (other). Data on staged resections are not available in the SEER database. Patients were assigned to one of three outcome categories: dead from GBC; dead from other causes, and alive at the end of the study.

Statistics

Summary statistics and Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). P-values for survival curves were determined by the log-rank test. Cox's proportional hazard regression analysis was performed incorporating variables with P < 0.1 on the log-rank test and the final model was built utilizing a stepwise selection method.

Results

Of 2788 patients with localized GBC, 300 (10.8%) and 536 (19.2%) had microscopically confirmed T1a or T1b disease, respectively, and 279 (10.0%) had T1NOS disease (Table 2). Female and White patients were more commonly represented. Thus, of these 1115 localized tumours, 300 (26.9%) represented T1a, 536 (48.1%) represented T1b and the remaining 279 (25.0%) represented T1NOS disease. Tumour size in those patients in whom it was reported was evenly distributed; however, tumour size was not reported in 942 (84.5%) patients. Of the 1115 patients with stage I GBC, 892 (80.0%) patients underwent cholecystectomy, only 168 (15.1%) underwent C + LN and 55 (4.9%) underwent RC. Only 97 (8.7%) patients received adjuvant radiation therapy.

Table 2.

Demographic and survival data for patients with stage I gallbladder carcinoma

| Variable | Patients, n (%) | 5-year survival | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSS, % | OS, % | ||

| Age, years | |||

| <50 | 85 (7.6) | 80% | 68% |

| 50–59 | 141 (12.6) | 63% | 55% |

| 60–69 | 214 (19.2) | 56% | 49% |

| 70–79 | 329 (29.5) | 53% | 37% |

| ≥80 | 346 (31.1) | 42% | 20% |

| P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 846 (75.9) | 54% | 39% |

| Male | 269 (24.1) | 55% | 37% |

| P = 0.725 | P = 0.560 | ||

| Race | |||

| White | 881 (79.0) | 53% | 38% |

| African-American | 90 (8.1) | 50% | 29% |

| Asian/Other | 144 (12.9) | 64% | 47% |

| P = 0.093 | P = 0.017 | ||

| Tumour stage I sub-stage | |||

| T1NOS | 279 (25.0) | 34% | 22% |

| T1a | 300 (26.9) | 70% | 54% |

| T1b | 536 (48.1) | 56% | 39% |

| P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Tumour size, cm | |||

| Unknown | 942 (84.5) | 52% | 37% |

| <1.0 | 44 (4.0) | 87% | 72% |

| 1.1–2.0 | 30 (2.7) | 51% | 37% |

| 2.1–3.0 | 36 (3.2) | 80% | 58% |

| 3.1–4.0 | 27 (2.4) | 46% | 40% |

| >4.0 | 36 (3.2) | 67% | 55% |

| P = 0.394 | P = 0.553 | ||

| Tumour grade | |||

| Well differentiated | 264 (23.7) | 68% | 49% |

| Moderately differentiated | 409 (36.7) | 56% | 40% |

| Poorly differentiated | 197 (17.7) | 26% | 15% |

| Undifferentiated | 19 (1.7) | 21% | 21% |

| Unknown | 226 (20.3) | 62% | 46% |

| P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Tumour histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 881 (79.0) | 51% | 36% |

| Neuroendocrine | 21 (1.9) | 95% | 81% |

| Papillary | 141 (12.6) | 76% | 46% |

| Other | 72 (6.5) | 30% | 25% |

| P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Surgery type | |||

| Cholecystectomy | 892 (80.0) | 50% | 35% |

| C + LN | 168 (15.1) | 70% | 53% |

| RC | 55 (4.9) | 79% | 48% |

| P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Lymph nodes examined, n | |||

| Unknown | 23 (2.1) | 62% | 50% |

| 0 | 855 (76.7) | 51% | 35% |

| 1–4 | 213 (19.1) | 65% | 49% |

| >5 | 24 (2.2) | 63% | 56% |

| P = 0.001 | P < 0.001 | ||

| Radiation therapy | |||

| No | 1004 (90.4) | 56% | 39% |

| Yes | 97 (8.4) | 33% | 28% |

| Unknown | 14 (1.2) | 48% | 48% |

| P < 0.005 | P < 0.087 | ||

DSS, disease-specific survival; OS, overall survival; T1NOS, tumour stage I not otherwise specified; C + LN, cholecystectomy plus lymph node dissection; RC, radical cholecystectomy.

Of the 1115 patients with stage I GBC, 421 (37.7%) were alive at the end of the study. The 694 deaths (62.2%) included 288 (41.5%) from GBC, 127 (18.3%) from other types of cancer, 133 (19.2%) from heart or vascular disease, eight (1.2%) from neurological disease, 21 (3.0%) from infection, 26 (3.7%) from lung disease, 11 (1.6%) from accident or suicide, 35 (5.0%) from other causes, and 45 (6.5%) from unknown causes. Median follow-up was 22 months (range: 7–244 months).

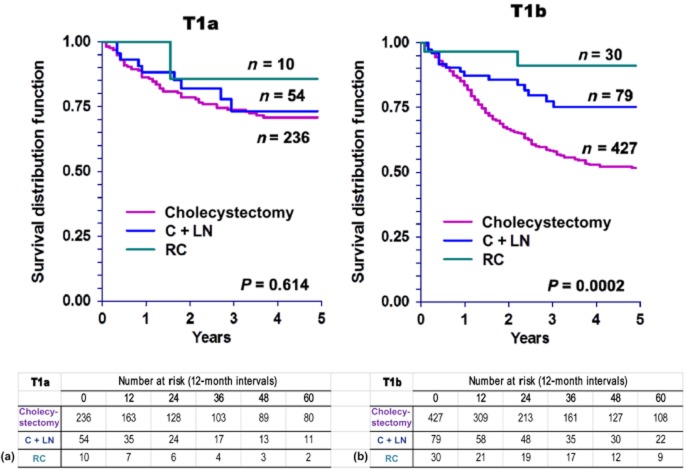

The type of surgery selected varied slightly by tumour stage, although the differences did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1). Patients with T1a and T1b disease were equally likely to undergo cholecystectomy alone [n = 236 (78.7%) vs. n = 42 (79.7%); P = 0.731], C + LN [n = 54 (18.0%) vs. n = 79 (14.7%); P = 0.258] or RC [n = 10 (3.3%) vs. n = 30 (5.6%); P = 0.055].

Figure 1.

Types of surgery performed in tumour stage I (T1) gallbladder carcinoma. Green bars, radical cholecystectomy; blue bars, cholecystectomy plus lymph node resection; purple bars, cholecystectomy only; T1NOS, T1 not otherwise specified

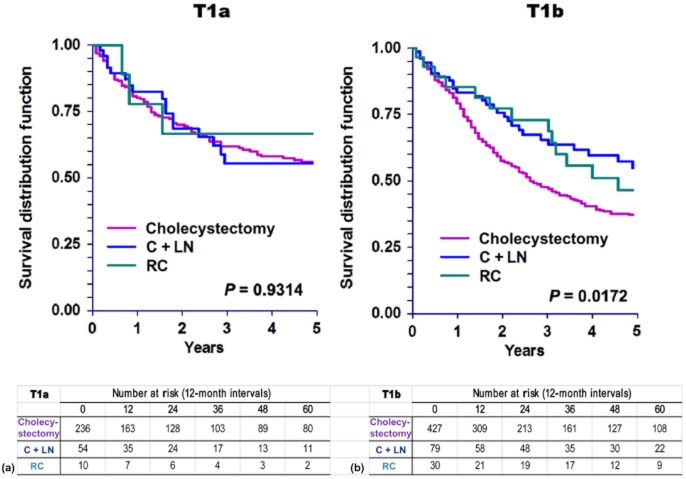

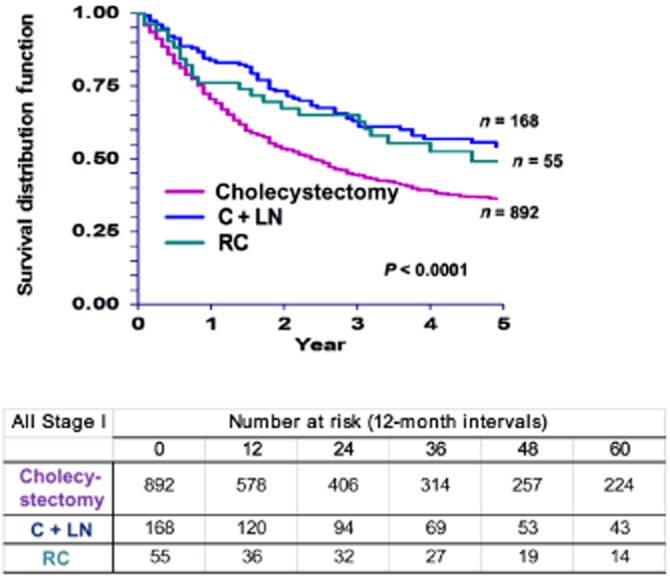

Based on univariate analysis, sex, race and tumour size had no significant effect on 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) in patients with T1 GBC (Table 2). Younger age (P < 0.001), T1a disease (P < 0.001) and examination of one or more LNs (P = 0.001) were associated with better DSS. Race was not a contributing factor (P = 0.934). Rates of DSS were also significantly higher after C + LN (70%) or RC (79%) than after cholecystectomy alone (50%) (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Disease-specific survival was shorter in patients who received radiation therapy.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for disease-specific survival in patients with tumour stage I (T1) gallbladder carcinoma by type of surgery (P < 0.0001). C + LN, cholecystectomy plus lymph node resection; RC, radical cholecystectomy

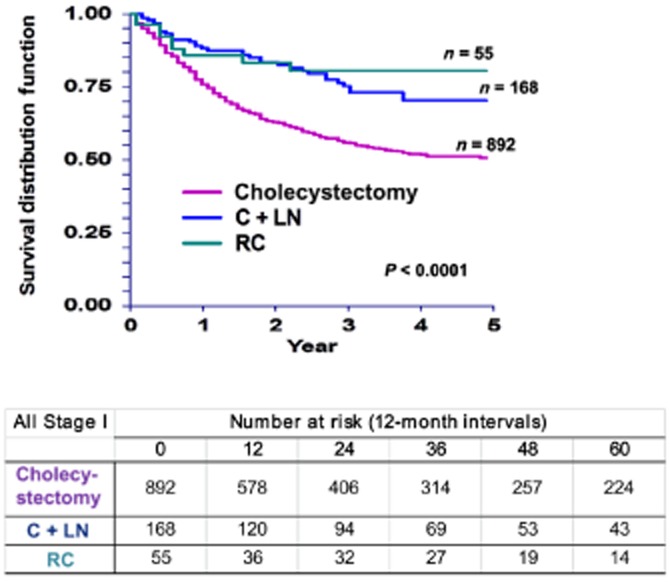

Five-year overall survival (OS) was not significantly affected by sex, tumour size or radiation therapy (Table 2). As might be expected, younger patients had significantly better survival than older patients (P < 0.001). Asians and Pacific Islanders with GBC achieved better survival than African-American and White patients (47% vs. 29%, respectively; P = 0.017). Similar to DSS, OS in patients with T1a disease was superior to that in those with T1b disease (54% and 39%, respectively; P < 0.001). Overall survival was significantly affected by the extent of surgery (Fig. 3). Patients who underwent C + LN or RC achieved better survival (53% and 48%, respectively) than patients treated with cholecystectomy alone (35%) (P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival in patients with tumour stage I (T1) gallbladder carcinoma by type of surgery (P < 0.0001). C + LN, cholecystectomy plus lymph node resection; RC, radical cholecystectomy

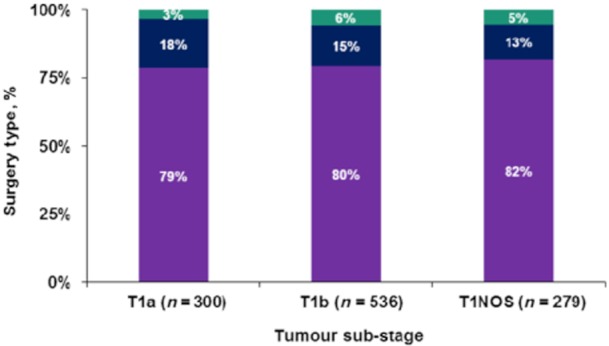

Further investigation regarding the role of surgical therapy based on T1 sub-stage revealed no DSS advantage in T1a patients who underwent more extensive surgery (C + LN or RC) compared with patients treated with cholecystectomy alone (Fig. 4a). However, T1b patients did benefit from more extensive surgery (Fig. 4b). These findings correlate with OS patterns in T1a and T1b patients (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves for disease-specific survival in patients with (a) tumour stage Ia (T1a) (P = 0.614) and (b) tumour stage Ib (T1b) (P = 0.0002) gallbladder carcinoma, by type of surgery. C + LN, cholecystectomy plus lymph node resection; RC, radical cholecystectomy

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival in patients with (a) tumour stage Ia (T1a) (P = 0.9314) and (b) tumour stage Ib (T1b) (P = 0.0172) gallbladder carcinoma. C + LN, cholecystectomy plus lymph node resection; RC, radical cholecystectomy

A multivariate Cox proportional hazard survival model was built using a stepwise selection method incorporating age, race, tumour sub-stage, tumour grade, tumour histology, radiation therapy and surgery type. Independent predictors for DSS were age, T1 sub-stage, tumour grade, tumour histology, radiation and surgery type. Independent predictors for OS were age, T1 sub-stage, tumour grade, tumour histology, race and surgery type. Table 3 gives the results of a Cox proportional hazard regression model in the entire stage I GBC cohort based on 5-year DSS and OS. Patients who underwent C + LN and RC had a significant DSS benefit over patients who underwent cholecystectomy alone [hazard ratio (HR) 0.501, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.353–0.710 (P = 0.001) and HR 0.410, 95% CI 0.218–0.814 (P = 0.006), respectively].

Table 3.

Adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression model for 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with stage I gallbladder carcinoma

| Variable: reference | Variables: comparison | 5-year disease-specific survival | 5-year overall survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age: <50 years | 50–59 years | 1.628 (0.889–2.981) | 0.114 | 1.260 (0.771–2.059) | 0.357 |

| 60–69 years | 1.922 (1.084–3.408) | 0.025 | 1.501 (0.947–2.379) | 0.084 | |

| 70–79 years | 1.923 (1.102–3.355) | 0.021 | 1.951 (1.256–3.031) | 0.003 | |

| >80 years | 2.608 (1.496–4.548) | 0.001 | 3.023 (1.949–4.687) | <0.001 | |

| Race: White | Black | N/A | N/A | 1.629 (1.236–2.148) | <0.005 |

| Other | N/A | N/A | 0.888 (0.688–1.144) | 0.357 | |

| Unknown | N/A | N/A | 0.000 (0.000–0.000) | 0.956 | |

| T1 sub-stage: T1a | T1b | 1.311 (0.989–1.739) | 0.060 | 1.240 (0.994–1.547) | 0.057 |

| T1NOS | 2.470 (1.845–3.307) | <0.001 | 1.931 (1.524–2.448) | <0.001 | |

| Surgery type: cholecystectomy alone | C + LN | 0.501 (0.353–0.710) | 0.001 | 0.638 (0.488–0.834) | 0.001 |

| RC | 0.410 (0.218–0.771) | 0.006 | 0.742 (0.490–1.122) | 0.157 | |

| Grade: well differentiated | Moderate | 1.483 (1.104–1.991) | 0.009 | 1.239 (0.985–1.558) | 0.067 |

| Poor | 2.696 (1.977–3.675) | <0.001 | 2.107 (1.642–2.704) | <0.001 | |

| Undifferentiated | 3.430 (1.885–6.242) | <0.001 | 2.233 (1.259–3.963) | 0.006 | |

| Unknown | 1.193 (0.843–1.688) | 0.318 | 1.048 (0.798–1.375) | 0.737 | |

| Histology: adenocarcinoma | Neuroendocrine | 0.129 (0.018–0.933) | 0.043 | 0.316 (0.116–0.865) | 0.025 |

| Papillary | 0.505 (0.338–0.756) | <0.009 | 0.594 (0.440–0.803) | <0.001 | |

| Other | 1.997 (1.431–2.789) | <0.001 | 1.734 (1.279–2.350) | <0.004 | |

HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; N/A, not available; T1NOS, tumour stage I not otherwise specified; C + LN, cholecystectomy plus lymph node dissection; RC, radical cholecystectomy.

Discussion

The standard of care in the surgical treatment of GBC remains controversial. Current recommended therapy for early GBC includes cholecystectomy for T1a tumours, and cholecystectomy with liver resection and periportal, gastrohepatic and retroduodenal LN dissection for T1b tumours.19 In this population-based cohort, 46.0% of patients with stage I GBC treated with cholecystectomy eventually died of GBC. By contrast, the risk for death from GBC appeared to significantly decrease when the operative procedure included the resection of any LNs and liver resection. Although this study found that most patients with T1b GBC received cholecystectomy alone, their survival differed significantly from that of patients with T1a or T1NOS disease. This may reflect the understaging of nodal disease in the absence of nodal sampling.

Nodal status is the most powerful predictor of outcomes in patients with stage I GBC.12,20,21 These data indicated improved survival when cholecystectomy was accompanied by LN resection (C + LN or RC). Although the results of Cox regression analysis demonstrated the prognostic importance of age in patients with stage I GBC, the improved survival associated with the examination of any LNs suggests a staging issue. This may be attributed to a stage migration phenomenon in which the better detection of disease results in more accurate staging.

Ogura et al.5 studied a multi-hospital cohort of 1686 Japanese patients who underwent radical resections for GBC. Of 201 patients with mucosal involvement only (T1a), 2.5% had LN metastases; of 165 patients in whom disease involved the muscularis propria (T1b), 15.6% had metastases in local LNs. Had these patients undergone cholecystectomy alone, their disease would have been staged strictly on the basis of the primary tumour. This highlights the distinction between primary tumour (T) stage, which is based on the depth (not size) of the initial lesion, and cancer stage, which incorporates nodal and metastatic components.

In order to adequately assess LN status, the guidelines of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) require the removal and pathologic examination of at least three regional LNs, which can include cystic, pericholedochal, retroportal, periduodenal, peripancreatic, coeliac and superior mesenteric nodes.16 Given that a majority of stage I GBC patients receive only cholecystectomy (77.0% in this cohort), this suggests that the majority of patients with stage I GBC may have been inadequately staged.

Shirai et al.22 used intra-lymphatic injection of indigo carmine to map the drainage pattern of gallbladder lymphatics in 21 patients with biliary tract cancer. The blue dye traced a path around the bile ducts, through the cystic LN, into the pericholedochal LNs and then into the retroportal and peripancreatic LNs. Others have examined the frequency of GBC nodal metastases by nodal basin. These studies indicate that the cystic and pericholedochal LNs are the most common sites of initial tumour spread.3,11,12

At the time of diagnosis, advanced GBC is likely to have spread to locoregional sites. As a result, chemotherapy is indicated, particularly when a negative margin (R0) resection is not achievable.23–27 However, the data are limited in advanced GBC and even more scant in stage I GBC. The role of adjuvant radiation in GBC also remains unclear.28 In this study, radiation therapy had a negative impact on survival. However, radiation therapy was applied in a limited number of patients and as all radiation was given postoperatively, radiation therapy may have been reserved for use in patients with a higher risk for recurrence.

No prospective trial has examined the impact of nodal surgery on outcomes in patients with stage I GBC. Most of the studies published during the last 21 years have been small, single-institution series with relatively short follow-up (Table 4). Given the infrequency of GBC and the rarity of its diagnosis in its earliest stages, the small numbers of patients in these studies is not surprising. Several studies have reported 5-year survival rates of 100%, but most of these included only two to 40 patients at selected institutions.3,4,9,11,29,30 To the authors' knowledge, the present study represents the largest population-based investigation of outcomes in patients with stage I GBC.

Table 4.

Clinical studies of patients with stage I gallbladder carcinoma published in the last 21 years

| Authors, year | Patients, n | Overall survival | Comment/treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median, months | 5 years, % | 10 years, % | |||

| Wibbenmeyer et al., 199531 | 2 | 16a | |||

| Yamaguchi et al., 199632 | 2 | Not mentioned | 100% at 2 years | ||

| Mingoli et al., 199733 | 2 | 6.5 | |||

| Kraas et al., 20029 | 2 | 100%a | |||

| Arnaud et al., 199529 | 4 | 100% | |||

| Shimada et al., 19973 | 4 | 100% | RC | ||

| Donohue et al., 19904 | 6 | 100% | Cholecystectomy, RC | ||

| Sarli et al., 200034 | 6 | 24a | Cholecystectomy | ||

| Gall et al., 199135 | 7 | 100 | 57% | ||

| North et al., 199836 | 7 | 24 | |||

| Whalen et al., 200137 | 11 | 19.5 | |||

| Kang et al., 200738 | 11 | Not mentioned | Cholecystectomy | ||

| Tsukada et al., 199711 | 15 | 76 | 91% | RC | |

| Sun et al., 200530 | 15 | 100% | Cholecystectomy | ||

| Cho et al., 201014 | 18 | Not mentioned | Cholecystectomy | ||

| de Aretxabala et al., 199739 | 24 | 87.50% | Cholecystectomy, RC | ||

| Suzuki et al., 20008 | 25 | 96% | Cholecystectomy | ||

| Wakai et al., 20017 | 25 | 90–95 | 87% | T1b/cholecsytectomy, RC | |

| Chan et al., 200640 | 33 | 87% | Cholecystectomy | ||

| Shirai et al., 199210 | 40 | 100% | Cholecystectomy, RC | ||

| Goetze & Paolucci, 201015 | 118 | 56 | 49–71% | Cholecystectomy, RC | |

| Ogura et al., 19915 | 366 | 78% | RC | ||

| Downing et al., 201112 | 683 | 33–93 | Cholecystectomy, C + LN, RC | ||

Approximate.

C + LN, cholecystectomy plus lymph node dissection; RC, radical cholecystectomy.

Although the use of the population-based SEER dataset minimized the risk for selection bias associated with smaller studies, the enormous size of the SEER database inevitably limits its detail on specific surgical and oncologic management. In addition, the SEER database was not designed to include data on comorbidities, which may be problematic in studies of elderly populations. Finally, in this study, 44.2% of patients were found to have died from unknown causes.

Because staging based strictly on the primary tumour may be inadequate in some patients with GBC, the present authors recommend that a combination of cholecystectomy and periportal or more extensive LN dissection be used when the patient's medical condition permits nodal staging of GBC. More accurate assessment of nodal status should improve the assessment of prognosis and thereby guide the selection of patients for clinical trials and for more rigorous follow-up.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the California Oncology Research Institute, the Joyce E. and Ben B. Eisenberg Foundation, the Rod Fasone Memorial Cancer Fund, the William Randolph Hearst Foundation and the Davidow Charitable Fund.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fong Y, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder cancer: comparison of patients presenting initially for definitive operation with those presenting after prior non-curative intervention. Ann Surg. 2000;232:557–569. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimada H, Endo I, Togo S, Nakano A, Izumi T, Nakagawara G. The role of lymph node dissection in the treatment of gallbladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79:892–899. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970301)79:5<892::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donohue JH, Nagorney DM, Grant CS, Tsushima K, Ilstrup DM, Adson MA. Carcinoma of the gallbladder. Does radical resection improve outcome? Arch Surg. 1990;125:237–241. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410140115019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogura Y, Mizumoto R, Isaji S, Kusuda T, Matsuda S, Tabata M. Radical operations for carcinoma of the gallbladder: present status in Japan. World J Surg. 1991;15:337–343. doi: 10.1007/BF01658725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muratore A, Polastri R, Capussotti L. Radical surgery for gallbladder cancer: current options. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:438–443. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakai T, Shirai Y, Yokoyama N, Nagakura S, Watanabe H, Hatakeyama K. Early gallbladder carcinoma does not warrant radical resection. Br J Surg. 2001;88:675–678. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki K, Kimura T, Ogawa H. Longterm prognosis of gallbladder cancer diagnosed after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:712–716. doi: 10.1007/s004640000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraas E, Frauenschuh D, Farke S. Intraoperative suspicion of gallbladder carcinoma in laparoscopic surgery: what to do? Dig Surg. 2002;19:489–493. doi: 10.1159/000067602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shirai Y, Yoshida K, Tsukada K, Muto T. Inapparent carcinoma of the gallbladder. An appraisal of a radical second operation after simple cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1992;215:326–331. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199204000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsukada K, Kurosaki I, Uchida K, Shirai Y, Oohashi Y, Yokoyama N, et al. Lymph node spread from carcinoma of the gallbladder. Cancer. 1997;80:661–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downing SR, Cadogan KA, Ortega G, Oyetunji TA, Siram SM, Chang DC, et al. Early-stage gallbladder cancer in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database: effect of extended surgical resection. Arch Surg. 2011;146:734–738. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fetzner UK, Holscher AH, Stippel DL. Regional lymphadenectomy strongly recommended in T1b gallbladder cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4347–4348. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i38.4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho JY, Han HS, Yoon YS, Ahn KS, Kim YH, Lee KH. Laparoscopic approach for suspected early-stage gallbladder carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2010;145:128–133. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goetze TO, Paolucci V. Adequate extent in radical re-resection of incidental gallbladder carcinoma: analysis of the German Registry. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2156–2164. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0914-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edge SS, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th edn. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2010. Gallbladder. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. 2010. Available at http://www.seer.cancer.gov (last accessed April 2012)

- 18.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance Research Program, SEER*Stat software. Version 7.0.5. 2010. Available at http://www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat (last accessed April 2012)

- 19.Miller G, Jarnagin WR. Gallbladder carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.07.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartlett DL, Fong Y, Fortner JG, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Longterm results after resection for gallbladder cancer. Implications for staging and management. Ann Surg. 1996;224:639–646. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199611000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayo SC, Shore AD, Nathan H, Edil B, Wolfgang CL, Hirose K, et al. National trends in the management and survival of surgically managed gallbladder adenocarcinoma over 15 years: a population-based analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1578–1591. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirai Y, Yoshida K, Tsukada K, Ohtani T, Muto T. Identification of the regional lymphatic system of the gallbladder by vital staining. Br J Surg. 1992;79:659–662. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eckel F, Schmid RM. Emerging drugs for biliary cancer. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2007;12:571–589. doi: 10.1517/14728214.12.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dutta U. Gallbladder cancer: can newer insights improve the outcome? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:642–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.07048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckel F, Brunner T, Jelic S. Biliary cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl. 5):65–69. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;362:1273–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hezel AF, Zhu AX. Systemic therapy for biliary tract cancers. Oncologist. 2008;13:415–423. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mojica P, Smith D, Ellenhorn J. Adjuvant radiation therapy is associated with improved survival for gallbladder carcinoma with regional metastatic disease. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:8–13. doi: 10.1002/jso.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnaud JP, Casa C, Georgeac C, Serra-Maudet V, Jacob JP, Ronceray J, et al. Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder – review of 143 cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:811–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun CD, Zhang BY, Wu LQ, Lee WJ. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for treatment of unexpected early-stage gallbladder cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:253–257. doi: 10.1002/jso.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wibbenmeyer LA, Wade TP, Chen RC, Meyer RC, Turgeon RP, Andrus CH. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy can disseminate in situ carcinoma of the gallbladder. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:504–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamaguchi K, Chijiiwa K, Ichimiya H, Sada M, Kawakami K, Nishikata F, et al. Gallbladder carcinoma in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 1996;131:981–984. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430210079015. discussion 985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mingoli A, Civitelli S, Sgarzini G, Ciccarone F, Corzani F, Puggioni A, et al. Influence of acute cholecystitis on surgical strategy and outcome of inapparent carcinoma of the gallbladder: a report on two cases. Anticancer Res. 1997;17(2B):1235–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarli L, Contini S, Sansebastiano G, Gobbi S, Costi R, Roncoroni L. Does laparoscopic cholecystectomy worsen the prognosis of unsuspected gallbladder cancer? Arch Surg. 2000;135:1340–1344. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.11.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gall FP, Kockerling F, Scheele J, Schneider C, Hohenberger W. Radical operations for carcinoma of the gallbladder: present status in Germany. World J Surg. 1991;15:328–336. doi: 10.1007/BF01658724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.North JH, Jr, Pack MS, Hong C, Rivera DE. Prognostic factors for adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder: an analysis of 162 cases. Am Surg. 1998;64:437–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whalen GF, Bird I, Tanski W, Russell JC, Clive J. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy does not demonstrably decrease survival of patients with serendipitously treated gallbladder cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:189–195. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang CM, Choi GH, Park SH, Kim KS, Choi JS, Lee WJ, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy only could be an appropriate treatment for selected clinical R0 gallbladder carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1582–1587. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Aretxabala XA, Roa IS, Burgos LA, Araya JC, Villaseca MA, Silva JA. Curative resection in potentially resectable tumours of the gallbladder. Eur J Surg. 1997;163:419–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan KM, Yeh TS, Jan YY, Chen MF. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for early gallbladder carcinoma: longterm outcome in comparison with conventional open cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1867–1871. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]