Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact, retention, and magnitude of effect of a required didactic and experiential palliative care curriculum on third-year medical students' knowledge, confidence, and concerns about end-of-life care, over time and in comparison to benchmark data from a national study of internal medicine residents and faculty.

Design

Prospective study of third-year medical students prior to and immediately after course completion, with a follow-up assessment in the fourth year, and in comparison to benchmark data from a large national study.

Setting

Internal Medicine Clerkship in a public accredited medical school.

Participants

Five hundred ninety-three third-year medical students, from July 2002 to December 2007.

Main outcome measures

Pre- and postinstruction performance on: knowledge, confidence (self-assessed competence), and concerns (attitudes) about end-of-life care measures, validated in a national study of internal medicine residents and faculty. Medical student's reflective written comments were qualitatively assessed.

Intervention

Required 32-hour didactic and experiential curriculum, including home hospice visits and inpatient hospice care, with content drawn from the AMA-sponsored Education for Physicians on End-of-life Care (EPEC) Project.

Results

Analysis of 487 paired t tests shows significant improvements, with 23% improvement in knowledge (F1,486=881, p<0.001), 56% improvement in self-reported competence (F1,486=2,804, p<0.001), and 29% decrease in self-reported concern (F1,486=208, p<0.001). Retesting medical students in the fourth year showed a further 5% increase in confidence (p<0.0002), 13% increase in allaying concerns (p<0.0001), but a 6% drop in knowledge. The curriculum's effect size on M3 students' knowledge (0.56) exceeded that of a national cross-sectional study comparing residents at progressive training levels (0.18) Themes identified in students' reflective comments included perceived relevance, humanism, and effectiveness of methods used to teach and assess palliative care education.

Conclusions

We conclude that required structured didactic and experiential palliative care during the clinical clerkship year of medical student education shows significant and largely sustained effects indicating students are better prepared than a national sample of residents and attending physicians.

Introduction

Education of medical students about end-of-life care, palliative care, and hospice care in most medical school curricula remains inadequate. Attention to this deficiency has accelerated in intensity, reflecting a national focus on improving end-of-life care.1,2 More than 2.5 million Americans will die in 2010. The majority will succumb to chronic progressive illnesses in which the patient and family know the cause of death well in advance.3 At least half those will experience pain, nausea, difficulty breathing, depression, fatigue, and other physical and psychological conditions that vastly diminish quality of life.4,5 The prevalence of these symptoms and situations appears to be similar for patients no matter what the underlying disease.5 Patients and families are unhappy with physicians' abilities to address these issues6 despite evidence that effective strategies exist.7 These factors reflect the critical need to improve education about palliative care for all physicians.

This need has stimulated private and public groups to determine core competencies physicians should possess to provide adequate care for patients and their families.8 These include knowing how to use clinical services in palliative care provided in hospitals and hospice programs. For many physicians, this is an important component of systems-based practice, an accreditation requirement in which “residents must demonstrate that they are aware of and responsive to the larger context and system of health care and can call on system resources effectively to provide optimal care.”9

The Liaison Committee for Medical Education, the accrediting body for all 130 medical schools in the United States and the 17 medical schools in Canada, requires all medical schools to include education in palliative care and end-of-life care.10 The Medical School Objectives Project identified “knowledge of the major ethical dilemmas in medicine, particularly those that arise at the beginning and end of life” and “knowledge about relieving pain and ameliorating the suffering of patients” as outcomes that all medical students should have achieved by graduation.11

Some courses on death and dying have been described.12–20 However, descriptions of instruction in end-of-life or palliative care indicate it consists predominately of didactic courses in death and dying during the preclinical years. The absence of immediate clinical application of the material likely limits educational effectiveness.21–24 In addition, there is evidence that the “hidden curriculum” in the clinical years blunts the effect of these preclinical educational efforts.25

A national study of palliative care in undergraduate medical education found that, although most medical schools offer some formal teaching of the subject, there is considerable evidence that current training is inadequate, most strikingly in the clinical years. The authors concluded that “curricular offerings are not well integrated; the major teaching format is the lecture; formal teaching is predominantly preclinical; clinical experiences are mostly elective; there is little attention to home care, hospice, and nursing home care; role models are few; and students are not encouraged to examine their personal reactions to these clinical experiences.”26

Corroborating these findings, the majority of senior medical students surveyed about the adequacy of their education on end-of-life issues reported that they were unprepared to deal with issues regarding end-of-life care, due to insufficient curricular time devoted to death and dying topics as well as lack of standardization of training and evaluation. Although respondents did report some experience with end-of-life care, only 52% of students report being present during a patient's death in a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) situation and 26% of students have not followed a terminally ill patient for 2 weeks or more.27

The objective of this study was to assess the impact, retention, and magnitude of effect of a required didactic and experiential palliative care curriculum on third-year medical students' knowledge, confidence, and concerns about end-of-life care, over time and in comparison to benchmark data from a national study of internal medicine residents and faculty.

Study Design and Methods

This educational intervention was conducted as a prospective longitudinal study. The hypotheses to be tested were:

Do measures of knowledge, attitudes, and skills improve after a 32-hour required curriculum in palliative care for junior medical students?

What evaluation instrument captures essential outcome information with the least testing burden to students?

What is the pattern of knowledge, attitudes, and skills retention in subsequent years of training using psychometrically equivalent instruments?

Learning objectives for each element of the curriculum are available from the corresponding author.

Curriculum development

The University of California, San Diego School of Medicine (UCSD SOM) requires all students to complete an independent study prior to graduation. The catalyst for our palliative care curriculum reform included the work of a fourth-year medical student, Wendy Evans, whose senior independent study project urged modifying existing, mostly classroom-based education in end-of-life care. The content was drawn from the Education for Physicians on End-of-Life Care (EPEC) curriculum,8 the national curriculum developed in collaboration with the AMA to establish the essential knowledge of palliative care for all U.S. physicians.

Evans persuaded the course director for the Ambulatory Block of the Internal Medicine Clerkship, Dr. Harry Bluestein, to increase curriculum time to 1 day per week for 4 weeks, during which students rotate to San Diego Hospice.

An Education Committee supervises the development and ongoing implementation of the curriculum. It is composed of the 19 full-time physician faculty who are certified by the American Board of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 2 nurse practitioners, 5 nurses, 1 social worker, and 1 chaplain. Although additional nonphysician staff function as faculty in the clinical setting, they are included by representation of their discipline leaders. The course director for the Internal Medicine elective is an ex officio member of this committee for the purposes of approving curriculum for the rotation.

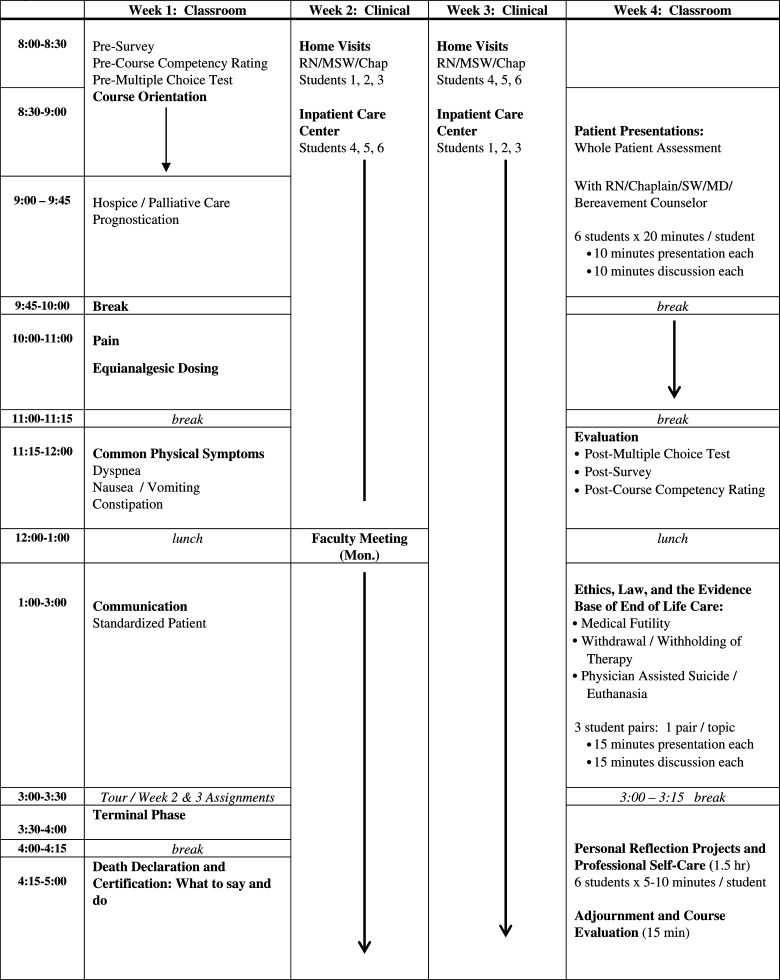

A 1-page schema of the curriculum is shown in Figure 1. A syllabus containing the material approved by the education committee is published in time for the beginning of the academic year, July 1. A faculty guide facilitates consistency between faculty. Syllabus materials are primarily drawn from the Education for Physicians on End-of-life Care (EPEC) project in order to ensure that the core competencies for physicians are transmitted.8 Other materials are drawn from the Residency Training Project in End-of-Life Care.28 In particular, the Fast Facts component of the education provides concise information useful to medical students and residents.29

FIG. 1.

Schema of curriculum. One day each week for 4 weeks during the 4-week ambulatory block of the 12-week internal medicine clerkship.

The syllabus is designed with the specific goal of providing a resource to students that will be useful in subsequent years. Consequently, more material is included than is “covered” in the sessions. The syllabus serves the additional purpose of stimulating self-directed learning.

A faculty guide for the delivery of the curriculum was prepared and given to all faculty. A yearly faculty development half-day seminar helps them with their small group facilitation skills. Physician fellows are given the guide, and then “see” and “do” one with faculty before doing the curriculum with medical students on their own.

The only challenges encountered in developing and implementing faculty development workshops were those of scheduling around other activities—and needed to be planned in advance. All faculty are interested in teaching and wanting to be better teachers

Data collection

To ensure correct identification for comparisons of performance over time and protect confidentiality, packets for each student were prepared that included pre- and posttests on which identification numbers were placed. Our experiences in a pilot study have shown the feasibility of our data collection methods.30

Main Outcome Measures

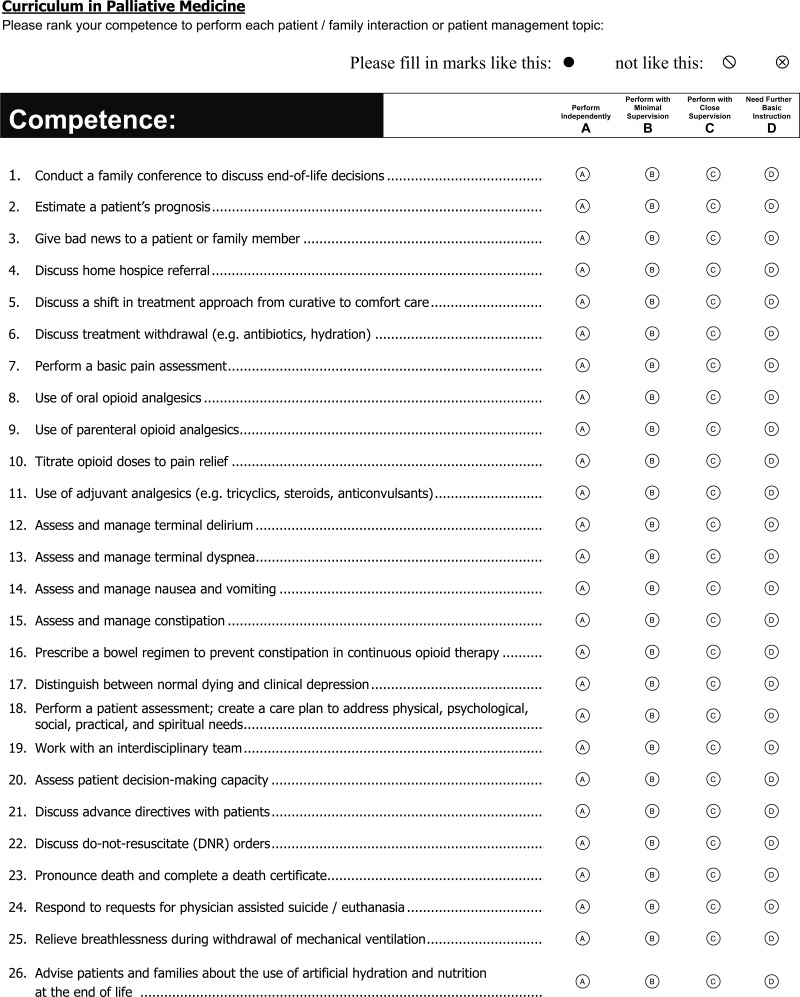

The primary end points for educational outcomes were measured using three validated instruments: (1) a 36-item knowledge test (Knowledge), (2) self-assessment of competency (Skill), and (3) self-assessment of concerns (Attitudes).40 The instruments are included in the Appendix. In addition, students completed written surveys intended to elicit their perspectives of the palliative care education experience. Each of the statements is one of self-efficacy. These reflect the advocacy of Bandura across a career's worth of work.

Analyses

Paired t tests were used to examine changes over time in students' knowledge, confidence, and concerns. We conducted analysis of variance on mean performance on these measures to identify potential differences over student cohorts completing their required palliative care rotations within third year rotations and across academic years. Analysis of students' written reflections used the constant comparison method of transcribed comments to identify themes, i.e., recurring unifying statements portraying the meaning of social phenomena to the participants. In order to reduce the burden of testing, we looked to see if the variation loaded onto a smaller number of questions; this was not the case. Consequently, the instruments as originally developed were used across the study period.

Results

One hundred percent of third-year medical students participated as this was a curriculum-evaluation project, where participation was compulsory. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) found the project to be exempt for this reason.

Knowledge

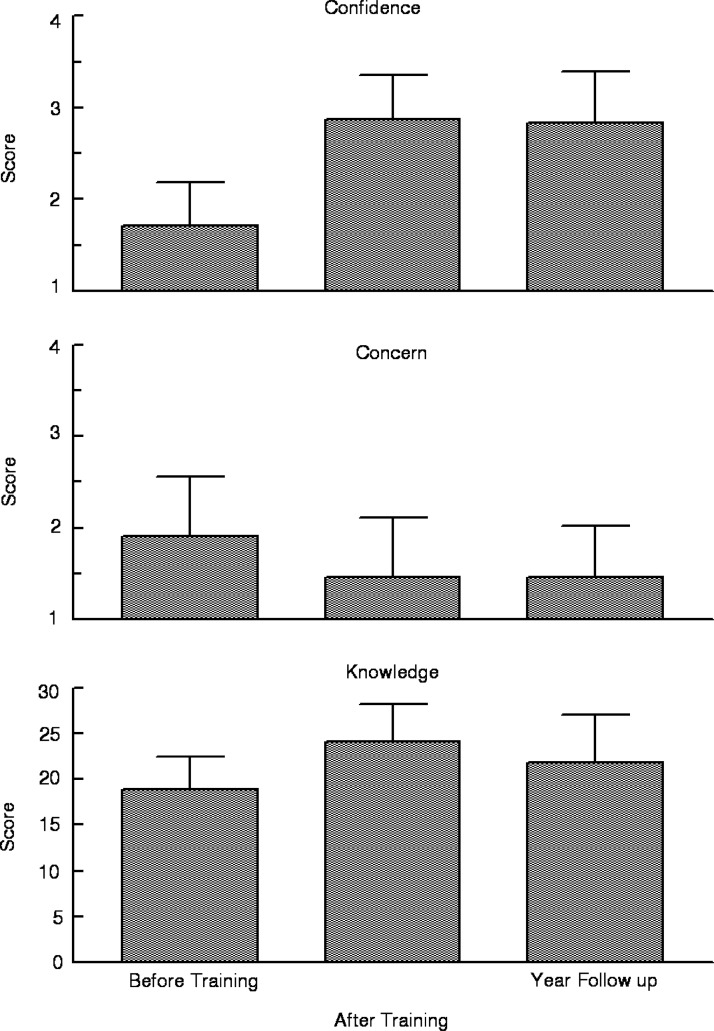

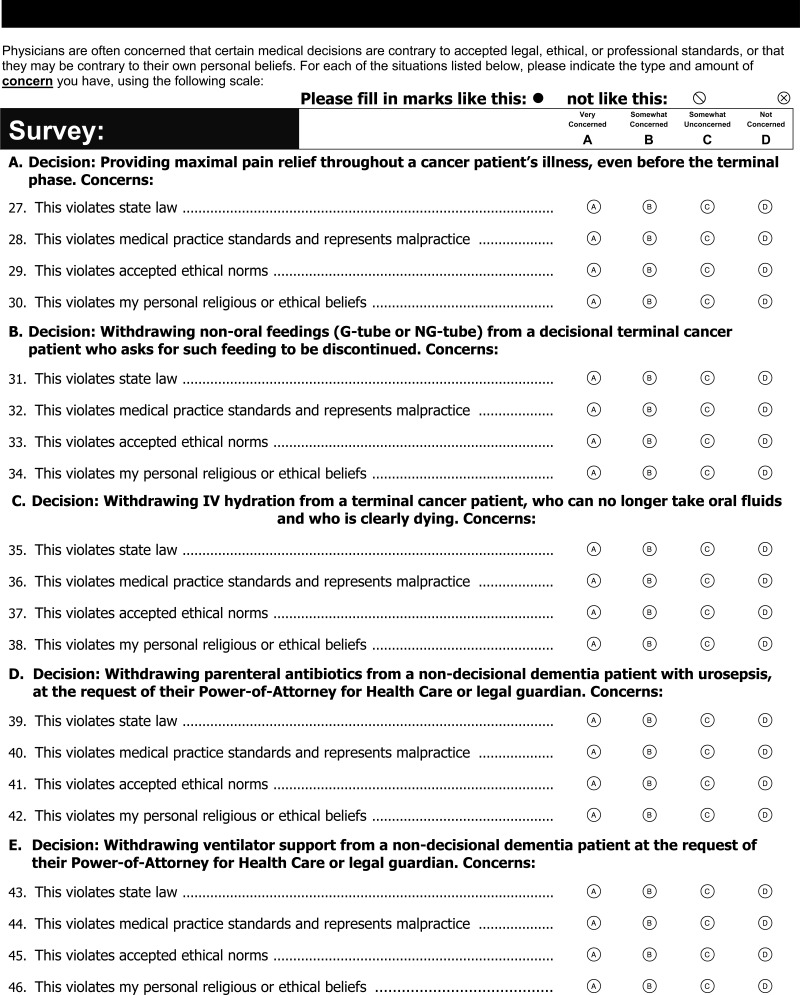

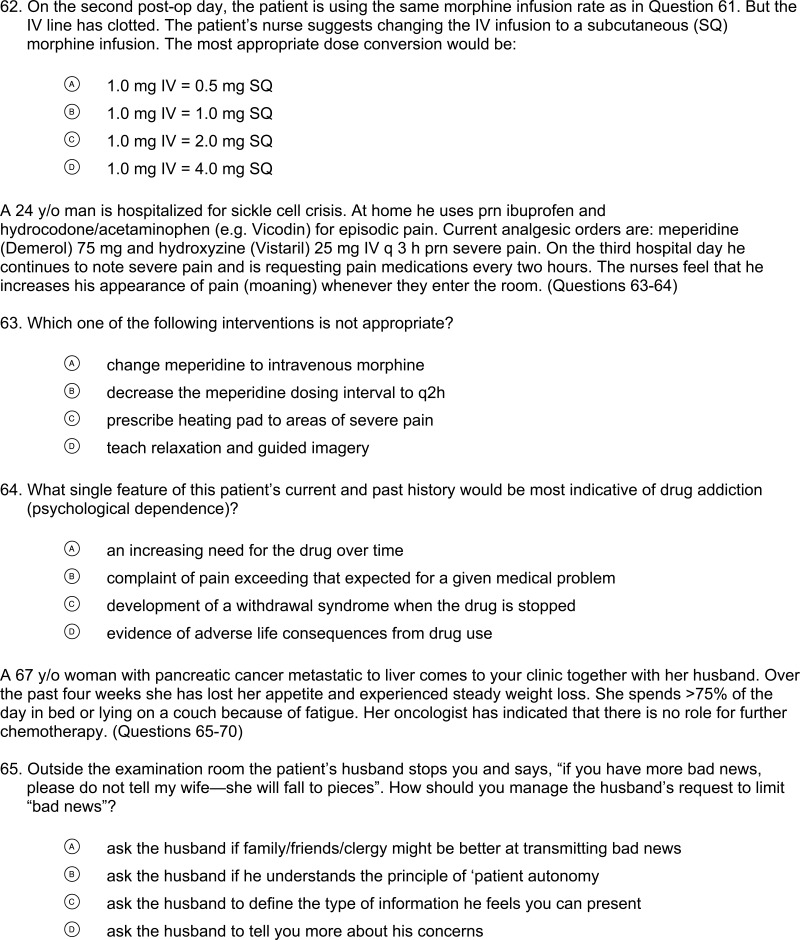

Analysis of 487 paired samples from third-year medical students demonstrated an improvement in knowledge from 52% correct to 67% correct (Fig. 2, lower panel, F1,486=881, p<0.001 paired t test).

FIG. 2.

Pre- and postscores from the third-year medical students and retest scores from fourth-year medical students.

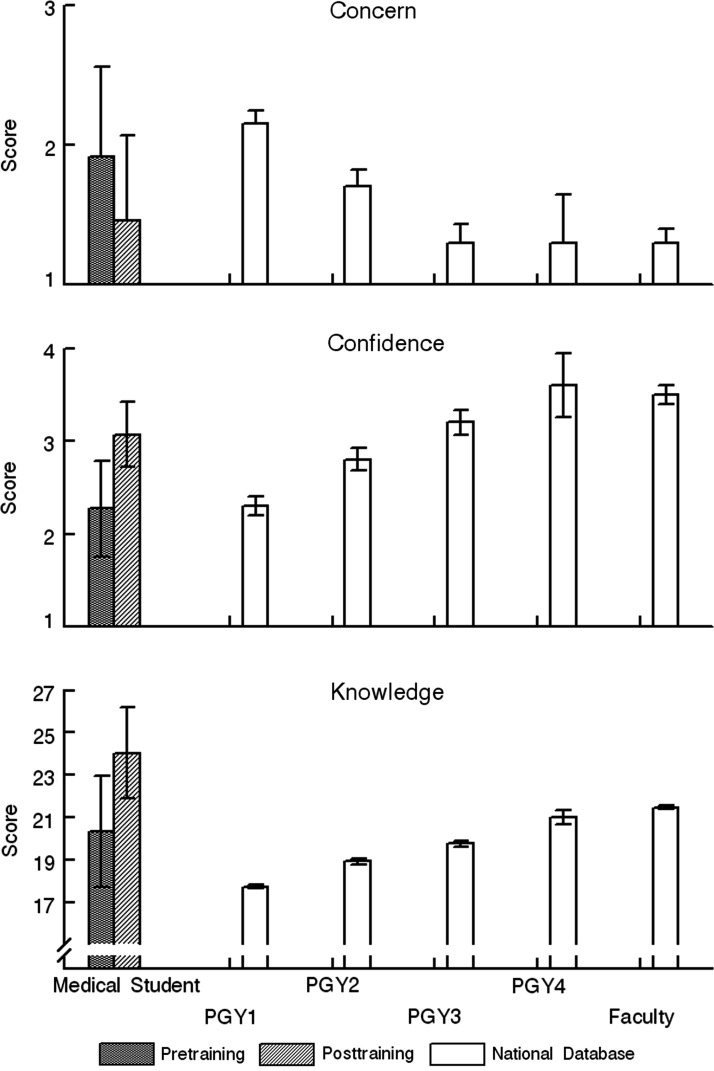

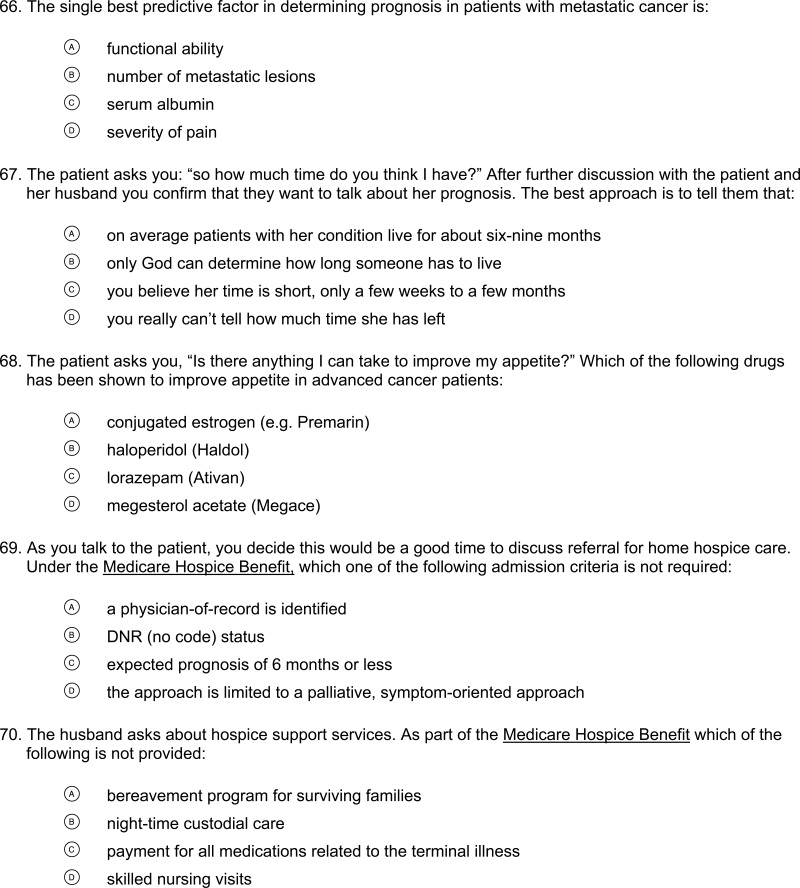

The students' pretest knowledge score is not different (p>0.775) from the 52% correct scored by postgraduate year 1 (intern) physician performance from the national sample of more than 10,000 internal medicine residents in their first, second and third years of training and their internal medicine attending faculty (Fig. 3, lower panel). In contrast, students' posttest knowledge score is higher than the score of 62% for physician faculty from the same national sample (Fig. 3, p<0.001)

FIG. 3.

Pre- and postscores from the third-year medical students shown with scores from a sample of 10,000 postgraduate year (PGY) 1 (intern), PGY-2, PGY-3, PGY4, and faculty from more than 400 internal medicine training programs in the United States.

The curriculum's effect size on M3 students' knowledge (0.56) exceeded the effect size found in the national cross-sectional study comparing the end-of-life care knowledge across progressive training levels (0.18)

We looked for evidence of learning across cohorts as the academic year progressed, and across academic years. The results did not indicate the presence of such differences.

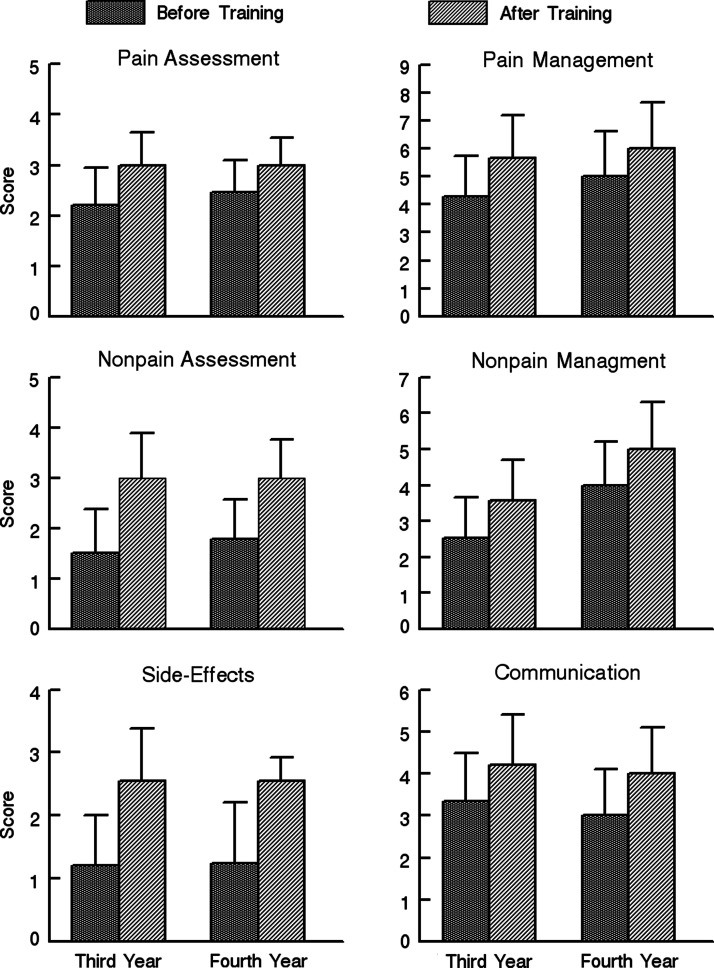

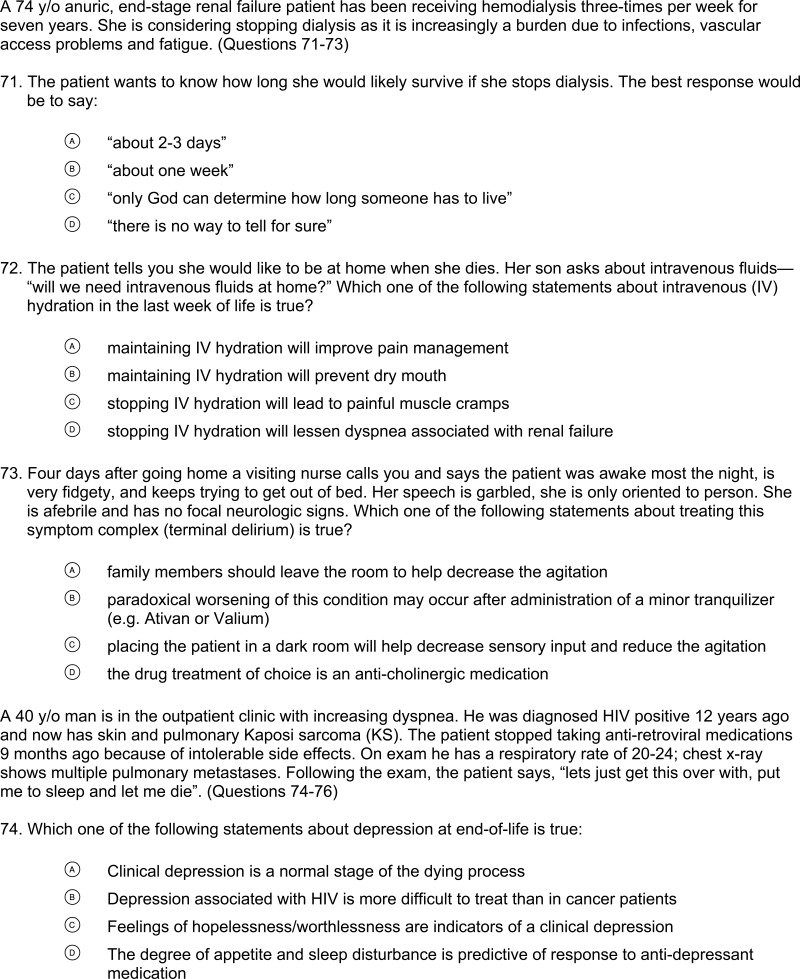

In subset analysis of knowledge, improvements in pain assessment, pain management, non-pain management or communication did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4). Improvements in non-pain assessment and side-effects knowledge did reach statistical significance (Fig. 4, F1,486=7.2, p=0.008; F1,486=4.37, p=0.04, respectively). The five questions with the most improvement were prescribing medication for opioid-induced constipation, dosing for breakthrough pain, custodial care provided by hospice programs at home, need for parenteral hydration for the dying patient, and use of opioids to treat dyspnea. The five biggest changes for “un-learning” in the MS4 group were: DNR requirements for hospice care, treating death rattle, treating terminal delirium, using opioids for dyspnea, and disclosing prognosis.

FIG. 4.

Knowledge subscale analysis for third-year medical students.

Competency

There was a 56% improvement in confidence from a score of 1.7 to 2.9 (Fig. 2, top panel, F1,486=2,804, p<0.001, paired t test) This scale uses a 4-point Likert type scale where 4=competent to perform independently, 3=competent to perform with minimal supervision, 2=competent for perform with close supervision, 1=need further basic instruction. In other words, medical students improve in self-assessed competency from needing close supervision to minimal supervision after completing the palliative medicine curriculum for the identified tasks. When compared with the performance of residents in the national sample, this corresponds to the competency greater than a second-year resident (Fig. 3, top panel, p<0.001).

Concern

Third-year medical students demonstrate a 29% decrease in level of concern from a score of 1.9 to 1.4 (Fig. 2, middle panel, F1,486=208, p<0 .001 paired t test). This scale uses a 4-point Likert type scale where 4=very concerned, 3=somewhat concerned, 2=somewhat unconcerned and 1=not concerned about legal and ethical issues in response to scenarios of maximal pain control, withdrawing antibiotics, withdrawing tube feeding and withdrawing IV hydration from terminally ill patients. This corresponds to an improvement greater than that demonstrated among second year residents (Fig. 3, 1.7, p<0.001) and third year resident and attending physicians (Fig. 3, 1.3, p<0.001)

Retention

Fourth-year medical students who experienced the curriculum show considerable retention of the information after one year. Although there is a decrease in the score on the knowledge examination from 68% to 59% (Fig. 2, p<0.001 paired t test), it does not return to the baseline level of 52%. Their final performance level is still higher than that for the national sample of interns and second year residents. There is no reason to think that students received additional palliative care education in their fourth year based on usual schedules.

Qualitative analysis

At the end of the course, students were asked open-ended questions about the curriculum. Almost all of the comments indicated that the students saw the course as effectively delivered. However, we recognize that the continuing impact of instruction is not dependent solely on the merit (technical adequacy and organization) of instruction. In this study, students' comments enable us to identify other features potentially affecting students' perception of the worth of the experience.

No students challenged the relevance of palliative care training or the grounding of the course in concepts and experiences intended to enhance students' understanding of humanism. Students' comments about the relevance of the course indicate most students perceived this training as relevant to all physicians, while a smaller portion of students considered the course useful for the “exposure” it provides. Others interpreted its relevance in terms of the particular specialty they intended to pursue. Furthermore, their comments indicate that they value instructional experiences promoting their reflection on the essential dignity of patients, as well as themselves. Finally, most students reported the multiple teaching methods and reflective exercises as well delivered. Their reservations focused on increasing the scope of their direct contact and participation in the care of patient and family care issues, while limiting the less interactive lecture components of the course. They also commented on the testing burden of the formal evaluation and the large amount of readings associated with the 4-day course.

Finally, we examined the results of the AAMC graduation questionnaire across the years of the curriculum. UCSD medical students rated their training in the top 1% nationally as compared with other medical schools.

Discussion

We conclude that a 4-day, 32-hour curriculum in end-of-life care leads to significant improvements in knowledge, skills, and attitudes that are sustained. Baseline assessments were stable across rotations and academic years, suggesting that the effects are not due to other changes in the medical school curriculum or in the larger social context. In addition, this also means students do not learn this material elsewhere in the clinical curriculum of the third year or the fourth year.

We chose the self-reported measurement of confidence to perform various skills because it had been used for the large comparative group of 10,000 internal medicine residents and faculty. In that setting, the choice is obvious because of the size of the group. Our need of a comparison group, and the size of our intervention, also favored the use of self-report. In further research, more focused evaluation of skills in a representative subset of students would be feasible.

Some who look at this data might be discouraged by the size of the absolute differences. Therefore, the statistical test of Effect Size is designed for situations like this. The Effect Size varies from 0–-1 where an effect less than 0.3 is small, 0,4–0.6 is moderate, and 0.7 to 1 is large. In the national sample, the effect size for change was 0.18. In contrast, the effect size for this intervention is 0.56—a moderately large effect.

This illustrates several important points about the evaluation instrument. First, the evaluation instruments were designed to cover all significant domains of palliative care—they were not designed to measure the achievement of specific learning objectives from a specific course. Consequently the instruments can be used across a variety of curricula, and an assessment of gain in the broad domain of palliative care can be discerned. For example, in our experience, only highly experienced faculty in the specialty of hospice and palliative medicine score 100%. Fellows studying in hospice and palliative medicine begin at the same level as medical students and rarely get out of the 70%–80% range despite an entire year of training. Therefore, the analogy to the thermometer is apt—a small change on the thermometer (from 37°C to 38.5°C on a 1–100 scale is tiny, but it is highly significant. The same is true for the instruments used in this study.

This curriculum is similar to that reported by the University of Maryland School of Medicine where they tested a required rotation in hospice and palliative medicine in the junior year. This module was received very positively by students and was ultimately made a mandatory part of the curriculum.31 At the University of Rochester,32 the introduction of a major curricular reform curriculum integrating basic science and clinical training over 4 years of medical school, provided an opportunity to develop and implement a fully integrated, comprehensive palliative care curriculum. Dr. David Weissman has developed a comprehensive program of hospice and palliative medicine education at the Medical College of Wisconsin over the past 20 years, which includes a required course for second- and third-year medical students and clinical electives for fourth-year medical students on the palliative medicine consultation service in the University Hospital and with affiliated hospice programs.18

The importance of clinical training in end-of-life care is reflected in the 2006 decision of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) to approve hospice and palliative medicine as a subspecialty. A unique and precedent setting event for ABMS is that 10 members of the ABMS agreed to implement certification in hospice and palliative medicine as a cooperative effort among 10 cosponsoring boards, representing anesthesiology, emergency medicine, family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychiatry and neurology, radiology, and surgery. The scope of the sponsoring Boards speaks strongly to the recognition that end-of-life care is highly valued across medical specialties.33–34

This study drew on several principles of best practices. For students to acquire the necessary attitudes, knowledge and skills of hospice and palliative medicine, such education should be longitudinal, a mixture of didactic and experiential learning opportunities, contain opportunities for self reflection, provide opportunities to practice the skills they are learning, and be interdisciplinary.

We postulated that students learn best when they are exposed to the direct care of patients who are being treated with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes the student needs to develop. When family members of patients who died are asked about quality of end-of-life care, hospice programs perform better than hospitals, nursing homes, and home care (without hospice care).6,35 Thus, we chose to imbed training in end-of-life care in a hospice setting within a required core internal medicine rotation. our results demonstrate that this approach successfully increases core knowledge and skills and decreases the level of concerns of learners who deal with the challenging issues surrounding death. It also demonstrates that a modest amount of instruction in the third year raises students' levels of knowledge to that of U.S. faculty.

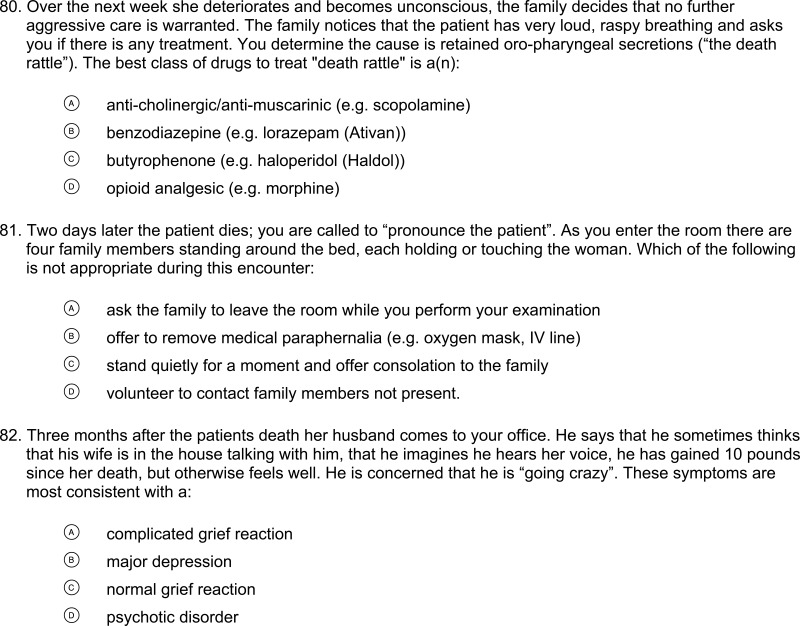

Our approach to educational reform reflects the understanding that curricular change requires “buy-in” from educational leaders as well as provision of resources.28,36–43 When deans and faculty recognize the value of instruction, finding time in the curriculum becomes easier.

Limitations of our study include the inclusion of a single medical school and the lack of random assignment of trainees to the educational intervention. To address such threats to internal validity frequently confronting medical education research, we incorporated design elements to mitigate these limitations.44 In our study, this included the use of benchmark data from a national study of residents and faculty, providing us with an empirical context from which to interpret the effect of our curricular training. In addition, we drew on the results of the Association of American Medical College's Graduation Questionnaire, to place our study's findings in the context of medical students' perceptions of end-of-life care education in other medical schools.

Another potential limitation is reflected in the extent of palliative care resources present in the study institution, for we recognize that the number of full time board-certified subspecialist palliative medicine physicians and subspecialty fellows and a dedicated hospice-based center for education and research are not broadly available in the United States. However, viewed another way, this is a strength. The study results were achieved with more than 40 different physician faculty suggesting that the results are not dependent on a single charismatic physician faculty member. Consequently, this is germane to the many hospice programs that host medical students as part of clinical clerkships.

The development of hospital-based palliative care teams can be seen as an effort to try to bring the skills developed in hospice programs into hospitals where they can be applied more broadly. Efforts to demonstrate patient-centered outcomes of such innovations are underway. As a way to ensure medical students are exposed to appropriate clinical care as part of a hospice and palliative medicine education curriculum, collaboration with a hospice program or palliative care team can be an important element.

Although developed with many physicians, our curriculum does not require hospice-based physicians to teach it. This offers encouraging evidence that the curriculum could be adopted effectively by other schools. Dedicated inpatient consultation services and units are rapidly multiplying in the United States. Clinical medical student training can effectively occur in this environment. These factors suggest that the curriculum and its results are “portable,” i.e., they could be extended to other training settings and populations.

For this curriculum a 50% time coordinator assured the students knew where to come and assembled the course materials for them. The syllabus was printed each year. Since the time of this study, it is now given to them on a “memory stick” The medical school covered the cost of developing the standardized patient for breaking bad news. The 16 hours of physician classroom time is required, which is the most expensive aspect of the course.

Acknowledgment

Supported by NCI R25 CA098389.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Field MJ, editor; Cassel CK, editor. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1997. Report from the Institute of Medicine Committee on Care at the End of Life. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynn J. Schall MW. Milne C. Nolan KM. Kabcenell A. Quality improvements in end of life care. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2000;26:254–267. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(00)26020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foley KM, editor; Gellband H, editor. National Cancer Policy Board of the Institute of Medicine and the National Research Council. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer: Summary, Recommendations. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emanuel LL. Librach SL. Palliative Care: Core Skills and Clinical Competencies. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teno JM. Clarridge BR. Casey V. Welch LC. Wetle T. Shield R. Mor V. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenz KA. Lynn J. Dy SM, et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:147–159. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emanuel LL, editor; von Gunten CF, editor; Ferris FD, editor. The Education for Physicians on End-of-Life Care (EPEC) Curriculum. Princeton, NJ: © The EPEC Project, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.www.acgme.org/outcome/e-learn/introduction/SBP.html. [Feb 28;2010 ]. www.acgme.org/outcome/e-learn/introduction/SBP.html

- 10.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Program Leading to the M.D. Degree. May, 2001.

- 11.The Medical School Objectives Writing Group: Learning objectives for medical student education: Guidelines for medical schools: Report I of the Medical School Objective Project. Acad Med. 1999;74:13–18. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grauel RR. Eger R. Finley RC, et al. Educational Program in Palliative and Hospice Care at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. J Cancer Educ. 1996;11:144–147. doi: 10.1080/08858199609528417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross DD. Keay T. Timmel D, et al. Required training in hospice and palliative care at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. J Cancer Educ. 1999;14:132–136. doi: 10.1080/08858199909528602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross DD. O'Mara A. Pickens N. Keay T, et al. Hospice and palliative care education in medical school: A module on the role of the physician in end-of-life care. J Cancer Educ. 1997;12:152–156. doi: 10.1080/08858199709528478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bishop M. Heaton J. Jaskar D. Collaborative end-of-life curriculum for fourth year medical students. Presented as module W-11 A collaborative end-of-life care curriculum at the 11th annual assembly of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; Snowbird, UT. Jun 23–26, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Policzer JS. Approach to teaching palliative medicine to medical students. Presented as module W-11 A collaborative end-of-life care curriculum at the 11th annual assembly of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; Snowbird, UT. Jun 23–26, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson AR. Savage MH. Travis T. Palliative care education—The first year's experience with a mandatory third-year medical student rotation at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Presented as module W-11 A collaborative end-of-life care curriculum at the 11th annual assembly of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; Snowbird, UT. Jun 23–26, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissman DE. Griffie J. Integration of palliative medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin 1990–1996. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;15:195–207. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(97)00265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burge FL. Latimer EJ. Palliative care in medical education at McMaster University. J Palliat Care. 1989;5:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steen PD. Miller T. Palmer L, et al. An introductory hospice experience for third-year medical students. J Cancer Educ. 1999;14:140–143. doi: 10.1080/08858199909528604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billings JA. Block S. Palliative care in undergraduate medical education. Status report and future directions. JAMA. 1997;278:733–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States General Accounting Office. Suicide Prevention: Efforts to Increase Research and Education in Palliative Care. p. 128. GAO/HEHS-98.

- 23.Barzansky B. Veloski J. Miller R. Jonas H. Palliative care and end-of-life education. Acad Med. 1999;74:S102–S104. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199910000-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Gunten CF. Secondary and tertiary palliative care in US hospitals. JAMA. 2002;287:875–881. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.7.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabow M. Gargani J. Cooke M. Do as I say: Curricular discordance in medical school end-of-life care education. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:759–769. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Billings JA. Block S. Palliative care in undergraduate medical education. Status report and future directions. JAMA. 1997;278:733–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraser HC. Kutner JS. Pfeifer MP. Senior medical students' perceptions of the adequacy of education on end-of-life issues. J Palliat Med. 2001;4:337–343. doi: 10.1089/109662101753123959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullan PB. Weissman DE. Ambuel B. von Gunten CF. End-of-life care education in internal medicine residency programs: An interinstitutional study. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:487–496. doi: 10.1089/109662102760269724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warm E. Fast facts and concepts: An educational tool. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:331–333. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter-Williamson K. von Gunten CF. Garman K. Berbst L. Bluestein HG. Evans W. Improving knowledge in palliative medicine with a required hospice rotation for third-year medical students. Acad Med. 2004;79:777–782. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200408000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross DD. Fraser HC. Kutner JS. Institutionalization of a palliative and end-of-life care educational program in a medical school curriculum. J Palliat Med. 2001;4:512–518. doi: 10.1089/109662101753381683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quill TE. Dannefer E. Markakis K, et al. An integrated biopsychosocial approach to palliative care training of medical students. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:365–380. doi: 10.1089/109662103322144682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Portenoy RK. Lupu DE. Arnold RM. Cordes A. Storey P. Formal ABMS and ACGME recognition of hospice and palliative medicine expected in 2006. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:21–23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.www.abms.org. [Feb 28;2009 ]. www.abms.org

- 35.von Gunten CF. Bedazzled by a home run. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1036–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bland D. Starnaman S. Wersal L. Moorehead-Rosenberg L, et al. Curricular change in medical schools: How to succeed. Acad Med. 2000;75:575–594. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Twaddle ML. Maxwell TL. Cassel JB. Liao S. Coyne PJ. Usher BM. Amin A. Cuny J. Palliative care benchmarks from academic medical centers. J Palliat Med. 2007 Feb;10(1):86–98. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weissman DE. Mullan PB. Ambuel B. von Gunten CF. End-of-life care curriculum reform: Outcomes and impact in a follow-up study of internal medicine residency programs. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:497–506. doi: 10.1089/109662102760269733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weissman DE. Mullan P. Ambuel B. von Gunten CF. Block S. End-of-life graduate education curriculum project: Project Abstracts/Progress Report—year 3. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:579–606. doi: 10.1089/109662101753381700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross RH. Fineberg HV. Medical students' evaluations of curriculum innovations at ten North American medical schools. Acad Med. 1998;73:258–265. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199803000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jablonover RW. Blackman DJ. Bass EB. Morrison G. Goroll AH. Evaluation of a national curriculum reform effort for the Medicine Core Curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:484–491. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.06429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mullan PB. Weissman D. von Gunten C. Ambuel B. Hallenbeck J. Coping with certainty: Perceived competency vs. training and knowledge in end of life care [abstract] J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:40. Supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weissman DE. Ambuel B. Von Gunten CF, et al. Outcomes from a national multispecialty palliative care curriculum development project. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:408–419. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lynch DC. Whitley TW. Willis SE. A rationale for using synthetic designs in medical education research. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2000;5:93–103. doi: 10.1023/A:1009875918096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]