Abstract

Palliative care programs are rapidly evolving in acute care facilities. Increased and earlier access has been advocated for patients with life-threatening illnesses. Existing programs would need major growth to accommodate the increased utilization. The objective of this review is to provide an update on the current structures, processes, and outcomes of the Supportive and Palliative Care Program at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (UTMDACC), and to use the update as a platform to discuss the challenges and opportunities in integrating palliative and supportive services in a tertiary care cancer center. Our interprofessional program consists of a mobile consultation team, an acute palliative care unit, and an outpatient supportive care clinic. We will discuss various metrics including symptom outcomes, quality of end-of-life care, program growth, and financial issues. Despite the growing evidence to support early palliative care involvement, referral to palliative care remains heterogeneous and delayed. To address this issue, we will discuss various conceptual models and practical recommendations to optimize palliative care access.

Introduction

Palliative care is a rapidly evolving discipline serving patients with life-threatening illnesses and addressing their physical, psychological, social, spiritual, communication, decision making, and end-of-life care needs. Modern hospice and palliative care started in the United Kingdom in the late 1960s.1 Initially, programs were inpatient hospices or community based. One of the limitations of the initial hospice movement was the very late referral and the fact that patients in the highest level of distress died in acute care facilities instead of hospices.2,3

During the 1980s, palliative care developed in Canada within academic acute care hospitals and cancer centers.4 Initially, these programs consisted of mobile teams and later acute palliative care units. During the 1990s, it became clear that outpatient programs were needed to access patients early in the trajectory of illness.5,6

The current structure of the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (UTMDACC) Supportive Care and Palliative Care Program is based on developmental work that took place in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.7 It is one of the most comprehensive supportive care programs among U.S. cancer centers,8 and is now regarded as a successful model for integration between palliative care and oncology.6 The objective of this review is to provide an update on the current structures, processes, and outcomes of our palliative and supportive care team, and to use it as a platform to discuss the challenges and opportunities in integrating palliative and supportive services in a tertiary care cancer center.

Structures of the UTMDACC Palliative Care Program

The Supportive and Palliative Care Program consists of three main structures, including an inpatient mobile consultation team, an acute palliative care unit, and an outpatient supportive care clinic.

1. The Mobile Team

There are currently three mobile teams, each including a physician, a midlevel provider, and/or a fellow, operating every day and seeing patients in all inpatient areas at UTMDACC including the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and the Emergency Center. The mobile teams have access to one counselor who is consulted according to severity of distress.

2. The Acute Palliative Care Unit

This 12-bed unit is staffed by a board certified palliative care physician, three to five nurses, a midlevel provider (advanced nurse practitioner or physician assistant), a palliative care or medical oncology fellow, a chaplain, a counselor, a social worker and a pharmacist. All the members of the interdisciplinary care team have received intensive palliative care training and orientation, and they communicate with each other closely throughout the day.

3. The Supportive Care Center

This outpatient clinic has a reception area and nine rooms, and is staffed by two palliative care physicians, four supportive care trained nurses, and a social worker. It operates from 8 am to 5 pm 5 days a week to ensure uninterrupted access to supportive care services.

Processes of the UTMDACC Palliative Care Program

1. The Mobile Team

Upon receipt of an online or pager referral, a dispatcher assigns new consults to each of the three mobile teams. The vast majority of patients are seen on the same day of the referral. Each morning the three mobile teams meet to discuss the existing cases, the staffing resources, and the overall plan for the day. Patients whose symptoms are controlled effectively or who are dying without major distress will be seen daily by the supportive care team while under the primary oncology service. In cases in which patient distress is severe or persistent, the mobile team discusses with the primary oncologist the possibility of transfer to the Acute Palliative Care Unit.

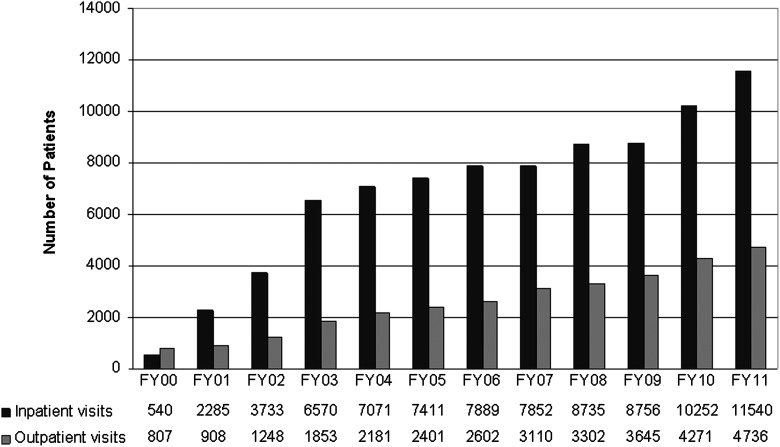

The mobile team service conducted 11,540 patient visits in 2011 (Fig. 1), including 2177 inpatient consultations.

FIG. 1.

Number of palliative care referrals between 2000 and 2011. Both inpatient and outpatient palliative care programs show steady growth.

2. The Acute Palliative Care Unit

Approximately 80% of the patients admitted to the Acute Palliative Care Unit are referred by the mobile team. The remaining 20% are patients who are primarily followed by Supportive Care and directly admitted from the outpatient clinic and Emergency Center. The main criterion for admission is the presence of severe physical and/or psychosocial distress. In addition to symptom management, the Acute Palliative Care Unit plays a critical role in caregiver support, transition of care, care of the dying, and discharge planning.

All patients admitted to the Acute Palliative Care Unit undergo daily assessment of physical and emotional distress by an interdisciplinary team coordinated by a palliative medicine physician using validated instruments, including the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS),9 the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS),10 and the CAGE questionnaire.11 For most patients, a family conference usually takes place within 48 to 72 hours of admission for the purpose of discussing further care and providing support for the family. These family conferences are regularly attended by the social worker, the chaplain, and the physician on staff in addition to the patient-designated family members. Other members of the interdisciplinary team, such as midlevel providers and nurses, often attend this meeting as well. There is also a weekly team meeting at the unit for the purpose of discussing all admitted patients as well as logistic issues. In addition to symptom management, our program also plays a critical role facilitating transition to end-of-life care, liaising with hospices, and educating patients and families about the role of hospice services.

The average number of admissions is 500 per year. The median length of stay is 7 days and approximately 70% of the patients are discharged alive.12 The median survival from admission to death is 21 days. This unit was established following the structure of the palliative care unit in Edmonton, and it has in turn been a template for multiple other institutions in the United States and around the world.

3. Supportive Care Center

Patients are referred to this center by their oncologists and other physicians at UTMDACC. Once patients arrive at the center, they are taken directly to a room by a patient service coordinator after vitals have been obtained. During all consultations and follow-up visits, the patients undergo comprehensive assessment by a trained supportive care nurse of physical and emotional distress as well as delirium, risk for chemical coping, family structure, and function. The information is then discussed by the nurse and the palliative medicine specialist who will visit with the patient. After the assessment by the palliative medicine specialist, it sometimes is necessary to ask the social worker to see the patient. Because the average census is approximately 25 patients per day and there is only one social worker, a process for prioritizing the approximately five patients who will undergo counseling takes place at that point.

Our Supportive Care Center has several unique features addressing the care needs for frail outpatients with advanced cancer. First, emphasis is made on physician coverage to ensure that patients have access to supportive care on the same day as the regular oncology visit in an effort to minimize patient transportation needs and distress. Second, patients in severe distress are encouraged to drop by the center where they will be seen without an appointment. Patients in distress in other centers can generally be seen on the same day at the center after a physician-to-physician referral. Third, patients in severe distress are registered within the “phone care nurse” program that consists of phone calls made by the nursing staff at the center a number of days after the visit. Patients are provided with the center phone number as well as an after-hours on-call number. Fourth, patients may undergo split visits in which the physician or social worker will meet with members of the family separately from the patient in an effort to discuss emotional issues or end-of-life care.

The center conducted 713 consultations and 4023 follow-up visits in 2011 (Fig. 1). Nineteen percent of the encounters were same-day consults or drop-in patients.

4. Interactions with primary teams and other specialties

The supportive care team works in close collaboration with the primary medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology teams, as well as with a number of consulting specialties both in the inpatient and outpatient setting such as interventional radiology, cardiology, respirology, infectious diseases, dermatology, and psychiatry.

Outcomes of the UTMDACC Palliative Care Program

1. Program growth and physician activity

Since the inception of our program, the number of referrals has increased above the growth of our institution as a whole and also of the Division of Cancer Medicine (i.e., medical oncology) (Fig. 1).13 The majority of activity continues to be inpatient.

The vast majority of the referrals are from clinical faculty within the different departments of the Division of Cancer Medicine. This is mostly due to the fact that medical oncologists are more often the primary team providing continuity of care for patients with advanced cancer. There has been a larger growth of the outpatient component between FY’08 and FY’10 that was not able to continue its growth for FY’11 because of saturation of staffing and clinic space.

The growth of our program may be related to multiple reasons, including a name change from “palliative care” to “supportive care,”14 the perception among oncologists that a supportive care referral can reduce the burden of high demand patients on the oncology clinic,15 and the effectiveness of our program to manage symptoms.16

2. Physical and psychosocial distress

Both the outpatient center and the inpatient services are capable of rapidly improving physical and emotional distress.17,18 In a recent study, we found a significant reduction of pain, fatigue, nausea, drowsiness, dyspnea, anorexia, sleep depression, and anxiety among 406 outpatients at their follow-up visit.18

3. Quality of care at the end of life

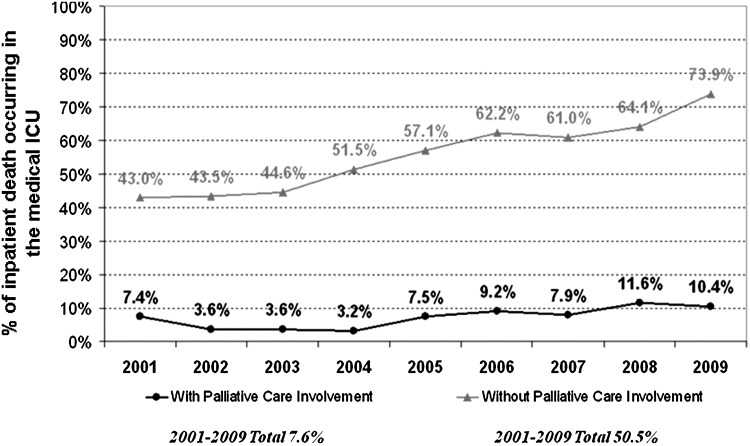

A number of quality of end-of-life care indicators have been developed.19,20 Figure 2 shows that the number of deaths in the medical ICU at UTMDACC has significantly increased over the years among patients who have never been seen by palliative care, constituting approximately 50% to 60% of all in-hospital deaths. In contrast, the proportion of medical ICU deaths has been consistently around 10% for patients who have been seen by our palliative care team, suggesting that palliative care referral is associated with less aggressive end-of-life care. The inception of our inpatient palliative care programs did not have any negative impact on overall inpatient mortality for UTMDACC.16

FIG. 2.

Proportion of inpatient death occurring in medical Intensive Care Units (ICU) between 2001 and 2009. A high proportion of patients without a palliative care consultation died in the ICU, and this continues to increase. In contrast, the percentage of medical ICU death stayed consistently low among patients with a palliative care consultation.

4. Perception of “palliative care” by oncologists and midlevel providers

Oncologists and midlevel providers are the gatekeepers for palliative care referral. To better understand their perception regarding palliative care, we conducted an anonymous survey of a random sample of 100 medical oncologists and 100 midlevel providers in our institution.15 The response rate was 70%. Both medical oncologists and midlevel providers regarded palliative care service as useful for addressing most physical and emotional issues.

We also found that >90% of the respondents answered that they would be equally likely to refer a patient to a service called “supportive care” or “palliative care” if the patient was not receiving any more active cancer treatment or was in transition to end-of-life. In contrast, they prefer “supportive care” over “palliative care” when the referral involves patients with earlier stages of the disease trajectory. A follow-up study comparing the number and timing of palliative care referral before and after the name change from “palliative care” to “supportive care” found a 46% increase in inpatient referral, and that patients were referred 1.6 months earlier in the outpatient clinic.14

5. Timing of palliative care referral

Despite the generally positive perception among oncology practitioners, late referral to palliative care remains a significant barrier for optimal patient care.21–23 Our recent data show that patients with advanced solid tumors were referred a median of 48 days before death, and those with hematologic malignancies were referred a median of 14 days before death. In contrast, the median time from advanced cancer diagnosis to death is 200 days, suggesting a significant delay in referral.

The median duration from referral to death for our program was 21 days for inpatient palliative care and 90 days for outpatient palliative care.14,24 Thus, the outpatient clinic remains the key tool for outpatient referral. The problem with late referral is that it does not allow for appropriate stabilization of physical, emotional distress, and advance care planning and this makes effective discharge to the community more complex.25

6. Financial aspects

The personnel cost associated with a robust palliative care program can be offset in two ways: (1) reimbursement for delivery of services, and (2) cost avoidance measures. We recently reported that patients admitted to our palliative care unit at MDACC had high rates of reimbursement.16 We also reported a lower cost of care compared with patients admitted under other services, which is likely related to a decrease in expensive modalities of care such as ICU admissions.16 Indeed, access to palliative care has the potential for major savings, primarily through cost avoidance by minimizing aggressive end-of-life care. An economic analysis conducted before and after the inception of the Edmonton Palliative Care Program in Canada showed that the implementation of supportive and palliative care resulted in significant decreases in inpatient costs.26

Barriers of integration

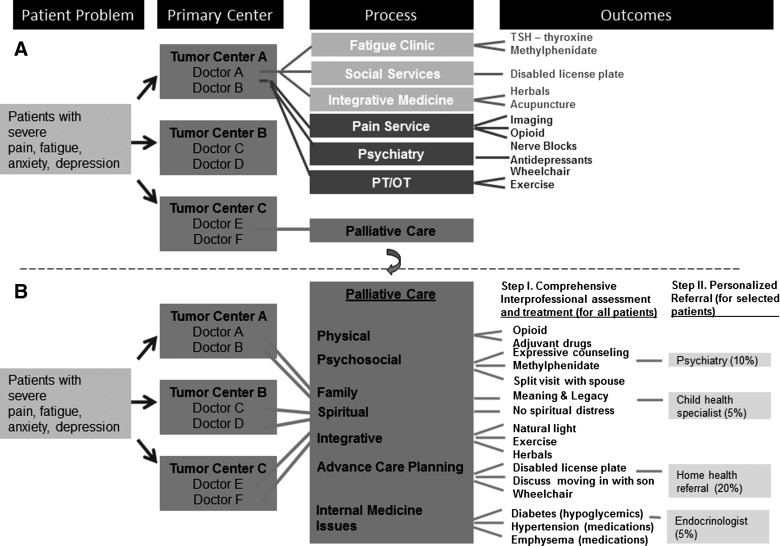

There are currently three major barriers to the integrated oncology care. First, the palliative care infrastructure is highly variable among cancer centers in the United States.8 Even among established programs such as ours, more resources are needed to support program growth. Second, referral to palliative care is heterogenous, and it is highly dependant on the individual clinician.27–29 As shown in Figure 3A, a patient with symptom concerns may be referred to one of many supportive care services depending on which symptom is detected and the clinician's preference. This can be confusing at best, and may result in fragmented and delayed care, duplication of services, and increased cost of care. Third, the timing of referral is often delayed for a vast majority of palliative care services in U.S. cancer centers.8

FIG. 3.

Patterns and process of referral for supportive care services. (A) Cancer patients presenting with severe symptoms may be referred to different supportive care services depending on which symptom is detected and the referral practice for each oncologist. This ranges from no referral at all (doctors C, D, and E), to involvement of selected services (doctors A and B) to palliative care referral (doctor F). (B) In this model of comprehensive cancer care, all patients with severe distress are referred to palliative care, and receive comprehensive assessment for their symptoms, communication and decision making needs, with the appropriate management provided by physicians, nurses, and counselors. Those with specific needs are then further referred to other services. This model ensures that supportive palliative care is delivered in a comprehensive, personalized and streamlined fashion.

To address these issues, we first need to ensure that adequate resources are in place for palliative care. The referral process could be improved significantly by building a clear conceptual framework for “palliative care,” developing an approach to discussing palliative care with patients and professionals, integrating palliative care into the oncology practice, and developing specific guidelines for referral. The Center to Advance Palliative Care also provides a list of resources for building a palliative care program and a set of metrics for program development.30

Conceptual models

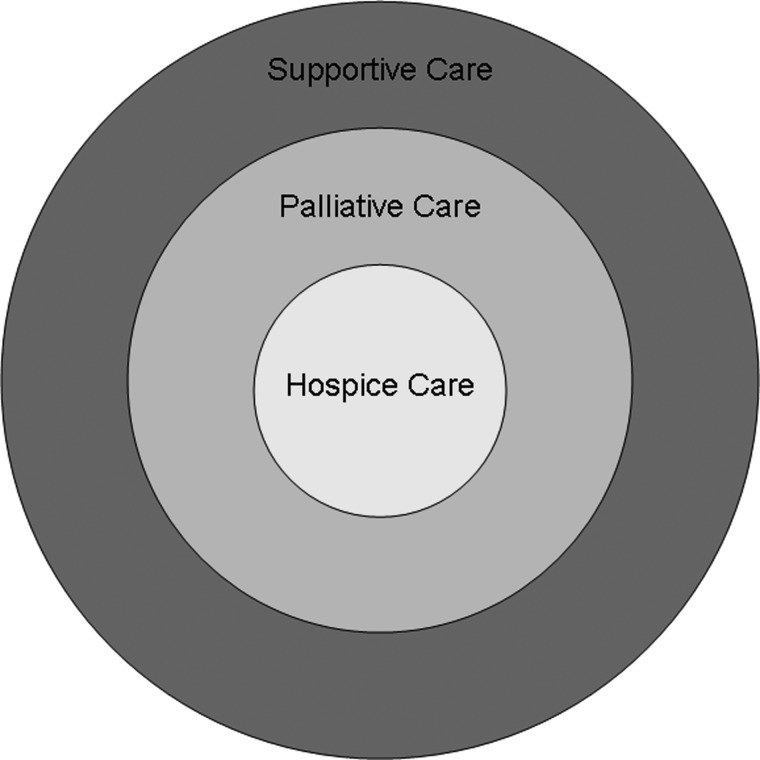

1. Conceptual Model #1: Defining supportive, palliative, and hospice care

The current definitions for supportive care and palliative care overlap significantly in the literature. The main definitions for both areas have been provided by the World Health Organization, the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology.31 Our team has been directly involved in all these organizations.

We recently conducted a systematic review of the peer-review literature to examine studies attempting to define these terms.32 A conceptual diagram is shown in Fig. 4. Under this model, “hospice care” is part of “palliative care,” which in turn is under the umbrella of “supportive care.” “Palliative care” predominantly addresses the care needs for patients with advanced cancer in both acute care facilities and the community, whereas “supportive care” provides an even broader range of services for patients throughout various stages of the disease, including diagnosis, active treatment, end-of-life, and survivorship. By changing the name of our program from “palliative care” to “supportive care,” we enlarged the referral base and extended our services to patients earlier in the disease trajectory.14 Of note, the practice of palliative care is by definition interprofessional in nature. In contrast, palliative medicine represents one discipline within this team.

FIG. 4.

Conceptual framework for “Supportive Care,” “Palliative Care,” and “Hospice Care.” “Hospice Care” is part of “Palliative Care,” which in turn is under the umbrella of “Supportive Care.” “Palliative Care” predominantly addresses the care needs for patients with advanced cancer in both acute care facilities and the community, whereas “Supportive Care” provides an even broader range of services for patients throughout various stages of the disease, including diagnosis, active treatment, end-of-life, and survivorship.32

2. Conceptual Model #2: Approach to introducing “palliative care.”

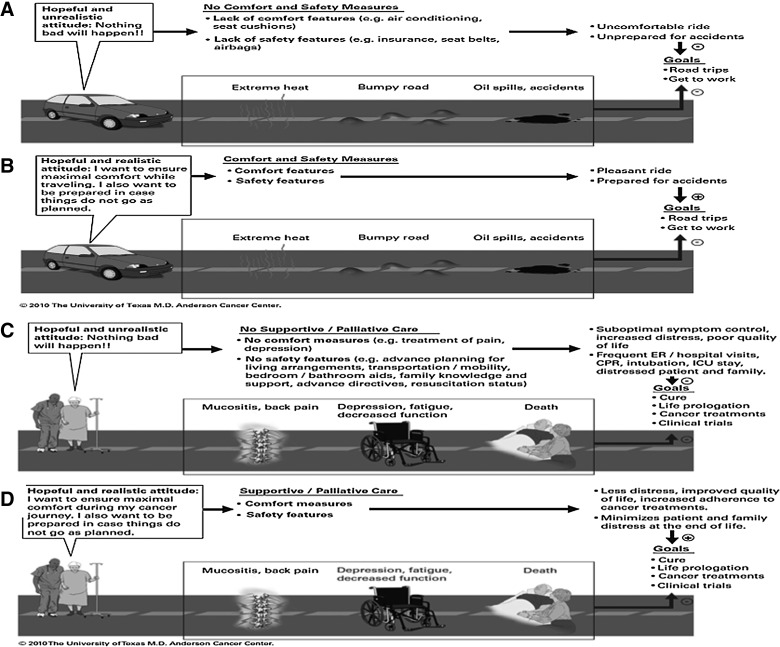

To address referring physicians' concerns that palliative care involvement denotes hopelessness, we have developed the model of Goals of Car(e).33 We often use this model to discuss the role of palliative care, advance care planning, and goals of care with our patients and oncology colleagues. Oncologists are in charge of coordinating care planning with patients and their families. In the vast majority of cases, patients' goals are to be cured or to stabilize the disease. This is quite understandable even if it may not be the final outcome. At the same time, it is important to help patients and families realize the concurrent goals of maximizing comfort along the cancer journey and being prepared for the challenges ahead. The use of a car analogy may help patients and their families understand the reasons for a referral to supportive/palliative care (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Conceptual model for Goals of Car(e). A car is used here as an analogy for establishing goals of care. (A) A hopeful unrealistic driver believes that there will be no troubles ahead in her journey. This is in contrasts to (B) a hopeful realistic driver who understands the importance of comfort measures and the need to prepare for the trip ahead. (C) A hopeful unrealistic patient who focuses on cancer treatments without attention to her symptoms and advance care needs may experience unnecessary distress. (D) In contrast, a hopeful and realistic patient who receives concurrent oncologic and supportive/palliative care would be better prepared for the symptoms and care needs ahead. Abbreviations: CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ER, emergency room; ICU, intensive care unit. Reprinted with permission from MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Figure 5A and 5B show two different goals for the use of a car. Although the primary goal is to travel between places, a person who does not take basic precautions such as buying insurance, wearing a seat belt, and protecting against extreme weather or rough roads will be exposed to unnecessary risks and discomfort (Fig. 5A). Because there are real possibilities of negative effects on the primary goal, the adoption of measures for comfort and safety do not denote a defeatist or hopeless attitude by the driver. Rather, they can reinforce enjoyment by improving the quality of the driving experience and providing peace of mind (Fig. 5B).

By the same token, the absence of any plans to manage physical and psychosocial distress and to prepare for the possibility of progressive disease should be considered unreasonable denial rather than hopefulness (Fig. 5C). Figure 5D shows the role of supportive and palliative care in maximizing physical and emotional care, supporting patients through cancer therapies, enhancing their adherence to treatments, facilitating transitions of care, and preparing patients and their families for the challenges ahead.

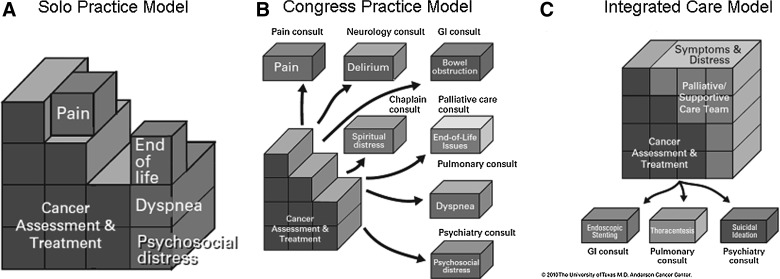

3. Conceptual Model #3: Integrating palliative care into oncology practice

There are three models for how oncologists can deliver supportive/palliative care to their patients: the Solo Practice Model, the Congress Practice Model, and the Integrated Care Model.33 Figure 6A (Solo Practice Model) shows the attempt by oncologists to provide all aspects of cancer management as well as supportive/palliative care. Regrettably, the vast majority of oncologists do not receive adequate undergraduate and postgraduate training in supportive/palliative care. Furthermore, systematic symptom screening is rarely done, resulting in under-diagnosis and under-treatment of many symptoms. Even with the skills and assessment tools, few oncologists have the time to address patients' physical and psychological concerns comprehensively. Oncologists encounter ever-increasing complexity in diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of malignancies, and the demand for oncology services is forecasted to increase overtime.34

FIG. 6.

The cancer care package. (A) In the Solo Practice Model, the oncologist provides both cancer assessment and treatment, and addresses a variety of supportive care issues such as pain and dyspnea. However, the lack of time and expertise means that these issues may not be managed adequately. (B) In the Congress Practice Model, the oncologist refers the patient to various specialities for all the supportive care issues. This could result in fragmented and expensive care. (C) In the Integrated Care Model, the oncologist routinely refers patients to palliative care for their supportive care needs. This helps to ensure patients receive comprehensive and integrated care, and it streamlines the provision of care. Reprinted with permission from MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Figure 6B (Congress Practice Model) shows the attempt by oncologists to provide supportive care by referring patients to multiple different specialists or disciplines. One of the problems associated with this type of practice is that patients suffering from multiple, severe physical and emotional symptoms and who are already under financial distress are referred to multiple clinics with different appointments where they undergo treatments that are potentially counter effective to other interventions.

Figure 6C (Integrated Care Model) shows our current model in which there is active collaboration between the oncologist and the supportive/palliative care team. This allows patients to obtain rapid resolution of multiple physical and emotional issues and a more personalized use of consultants. This model has been used by our center in both the inpatient and outpatient operations. The main limitation has been limited penetration of this model among referring colleagues.

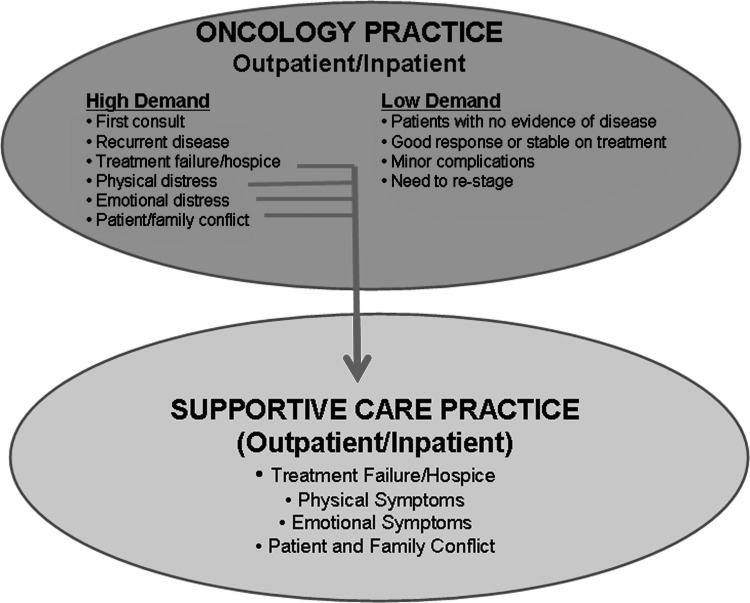

4. Conceptual Model #4: Criteria for palliative care referral

Given that oncologists are usually the main sources of referral, a better understanding of the nature of patients seen at oncology clinics can be helpful. A typical day consists of a mix of low- and high-demand visits (Fig. 7). Low-demand visits require little time for each encounter, and generally can be conducted well with few concerns. Patients with mild symptoms and who are well managed by their oncologists under the Solo Practice Model (Fig. 6A) may not require a referral to palliative care. In contrast, high-demand visits often require more time and resources to conduct an in-depth history, physical, and investigation and to discuss treatment options related to cancer and/or symptoms. Patients in distress and/or having transition of care needs are particularly in need of palliative care referral, where they have access to interdisciplinary assessment and management under an Integrated Care Model (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 7.

Criteria for palliative care referral. A typical oncology practice consists of high-demand patients and low-demand patients. High-demand patients with physical or emotional distress, refractory disease, or need for transition of care would benefit from routine referral to supportive care for further management.

Our model is consistent with the classification of palliative care services proposed by von Gunten,35 in which low-demand patients would benefit from primary palliative care delivered by their oncologists, and patients with more severe distress would require secondary and tertiary palliative care provided by a specialist interdisciplinary teams.

5. Conceptual Model #5: Comprehensive and personalized palliative care

Figure 3B operationalizes the Integrated Care Model proposed in Figure 6C. Under this model, all referred patients first undergo universal systematic assessments for physical, psychological, and spiritual concerns, and also for communication and decision making needs by an interprofessional team. Based on these assessments, a comprehensive management plan is delivered, including patient education, family support, and various pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions tailored to the individual's needs. Comorbidities also are addressed in a majority of cases. Patients in severe distress or who have specialized needs are referred to other services (e.g., pulmonary medicine for thoracentesis, pain service for nerve blocks, endocrinology for diabetic management). This approach ensures that patients receive a high standard of supportive care addressing the multiple and often intertwined symptom concerns, minimizes duplication of services by appropriately triaging, and optimizes personalized patient care interventions.

An alternative to this approach would be to have internal medicine or primary care, instead of palliative care, address all the supportive care issues. Although co-existing medical illness would be well managed, the symptom management, psychosocial support, and goals of care aspects might not be adequately addressed. In contrast, the palliative care team is well equipped to manage both the symptom concerns and co-existing illnesses, making it an ideal choice for partnering with oncology to deliver comprehensive cancer care.

Summary

We discussed barriers to successful integration of palliative care within the continuum of cancer care. We have also identified solutions that allowed our program to improve palliative care access within our institution. The conceptual models discussed, coupled with the growing evidence base and increasing recognition of the importance of palliative care, will hopefully help programs at earlier stages of development to flourish over time.

Author Disclosure Statement

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants RO1NR010162-01A1, RO1CA122292-01, and RO1CA124481-01 (Dr. Bruera). This study is also supported by an institutional startup grant 8075582 (Dr. Hui) and an MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management analysis, and interpretation of the data and preparation review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Clark D. von Gunten C. The development of palliative medicine in the UK and Ireland. In: Bruera E, editor; Higginson IJ, editor; Ripamonti R, editor; Textbook of Palliative Medicine. London: Hodder Arnold; 2006. pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukui S. Fujita J. Tsujimura M. Sumikawa Y. Hayashi Y. Fukui N. Late referrals to home palliative care service affecting death at home in advanced cancer patients in Japan: A nationwide survey. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2113–2120. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teno JM. Shu JE. Casarett D. Spence C. Rhodes R. Connor S. Timing of referral to hospice and quality of care: Length of stay and bereaved family members' perceptions of the timing of hospice referral. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDonald N. von Gunten C. The development of palliative care in Canada. In: Bruera E, editor; Higginson IJ, editor; Ripamonti R, editor; Textbook of Palliative Medicine. London: Hodder Arnold; 2006. pp. 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meier DE. Beresford L. Outpatient clinics are a new frontier for palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:823–828. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferris FD. Bruera E. Cherny N. Cummings C. Currow D. Dudgeon D, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruera E. Neumann CM. Gagnon B. Brenneis C. Kneisler P. Selmser P, et al. Edmonton Regional Palliative Care Program: Impact on patterns of terminal cancer care. CMAJ. 1999;161:290–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hui D. Elsayem A. De la Cruz M. Berger A. Zhukovsky DS. Palla S, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruera E. Kuehn N. Miller MJ. Selmser P. Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breitbart W. Rosenfeld B. Roth A. Smith MJ. Cohen K. Passik S. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:128–137. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui D. Elsayem A. Palla S. De La Cruz M. Li Z. Yennurajalingam S, et al. Discharge outcomes and survival of patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:49–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dev R. Miles M. Del Fabbro E. Vala A. Hui D. Bruera E. Growth of an academic palliative medicine program at a comprehensive cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.015. (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalal S. Palla S. Hui D. Nguyen L. Chacko R. Li Z, et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2011;16:105–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fadul N. Elsayem A. Palmer JL. Del Fabbro E. Swint K. Li Z, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: What's in a name?: A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 2009;115:2013–2021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsayem A. Swint K. Fisch MJ. Palmer JL. Reddy S. Walker P, et al. Palliative care inpatient service in a comprehensive cancer center: Clinical and financial outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2008–2014. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yennurajalingam S. Zhang T. Bruera E. The impact of the palliative care mobile team on symptom assessment and medication profiles in patients admitted to a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:471–475. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yennurajalingam S. Urbauer DL. Casper KL. Reyes-Gibby CC. Chacko R. Poulter V, et al. Impact of a palliative care consultation team on cancer-related symptoms in advanced cancer patients referred to an outpatient supportive care clinic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010 Aug 4; doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.03.017. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Earle CC. Park ER. Lai B. Weeks JC. Ayanian JZ. Block S. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1133–1138. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNiff KK. Neuss MN. Jacobson JO. Eisenberg PD. Kadlubek P. Simone JV. Measuring supportive care in medical oncology practice: Lessons learned from the quality oncology practice initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3832–3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrell BR. Late referrals to palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2588–2589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morita T. Akechi T. Ikenaga M. Kizawa Y. Kohara H. Mukaiyama T, et al. Late referrals to specialized palliative care service in Japan. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2637–2644. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morita T. Miyashita M. Tsuneto S. Sato K. Shima Y. Late referrals to palliative care units in Japan: Nationwide follow-up survey and effects of palliative care team involvement after the Cancer Control Act. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hui D. Parsons H. Nguyen L. Palla SL. Yennurajalingam S. Kurzrock R, et al. Timing of palliative care referral and symptom burden in phase 1 cancer patients: A retrospective cohort study. Cancer. 2010;116:4402–4409. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braiteh F. El Osta B. Palmer JL. Reddy SK. Bruera E. Characteristics, findings, and outcomes of palliative care inpatient consultations at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:948–955. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruera E. Neumann CM. Gagnon B. Brenneis C. Quan H. Hanson J. The impact of a regional palliative care program on the cost of palliative care delivery. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:181–186. doi: 10.1089/10966210050085241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beccaro M. Costantini M. Merlo DF. Group IS. Inequity in the provision of and access to palliative care for cancer patients. Results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer (ISDOC) BMC Public Health. 2007;7:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burge FI. Lawson BJ. Johnston GM. Grunfeld E. A population-based study of age inequalities in access to palliative care among cancer patients. Med Care. 2008;46:1203–1211. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d931d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Currow DC. Abernethy AP. Fazekas BS. Specialist palliative care needs of whole populations: A feasibility study using a novel approach. Palliat Med. 2004;18:239–247. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm873oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Center to Advance Palliative Care. www.capc.org/ [May 29;2012 ]. www.capc.org/

- 31.Hui D. Mori M. Parsons H. Li ZJ. Damani S. Evans A, et al. The lack of standard definitions in the supportive and palliative oncology literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hui D. De La Cruz M. Mari M. Parsons HA. Kwon JH. Torres I. Kim SH. Dev R. Hutchins R. Liem C. Kang DH. Bruera E. Concepts, definitions for “palliative care,” “supportive care,” “best supportive care,”, “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, textbooks. Supp Care Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1564-y. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruera E. Hui D. Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: Establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4013–4017. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erikson C. Salsberg E. Forte G. Bruinooge S. Goldstein M. Future supply and demand for oncologists: Challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Gunten CF. Secondary and tertiary palliative care in US hospitals. JAMA. 2002;287:875–881. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.7.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]