Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this prospective case-control study was to survey the detection rate of respiratory viruses in children with Kawasaki disease (KD) by using multiplex reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and to investigate the clinical implications of the prevalence of respiratory viruses during the acute phase of KD.

Methods

RT-PCR assays were carried out to screen for the presence of respiratory syncytial virus A and B, adenovirus, rhinovirus, parainfluenza viruses 1 to 4, influenza virus A and B, metapneumovirus, bocavirus, coronavirus OC43/229E and NL63, and enterovirus in nasopharyngeal secretions of 55 KD patients and 78 control subjects.

Results

Virus detection rates in KD patients and control subjects were 32.7% and 30.8%, respectively (P=0.811). However, there was no significant association between the presence of any of the 15 viruses and the incidence of KD. Comparisons between the 18 patients with positive RT-PCR results and the other 37 KD patients revealed no significant differences in terms of clinical findings (including the prevalence of incomplete presentation of the disease) and coronary artery diameter.

Conclusion

A positive RT-PCR for currently epidemic respiratory viruses should not be used as an evidence against the diagnosis of KD. These viruses were not associated with the incomplete presentation of KD and coronary artery dilatation.

Keywords: Coronary aneurysm, Mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, Respiratory tract infections, Viruses, Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

Introduction

Respiratory symptoms are frequently observed in children with Kawasaki disease (KD) during the acute phase. The association rate of KD with antecedent respiratory illness has been reported to be 56 to 83%1,2). Laboratory evaluation for detection of respiratory viruses is occasionally performed in febrile children with respiratory symptoms before confirmation of the diagnosis of KD. Recently, molecular diagnostic tests, such as real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), have been more frequently used as a laboratory method, because molecular diagnostic tests for the detection of all epidemic respiratory tract infection-related viruses allow a thorough etiological assessment and better management of children with respiratory tract infection3). However, we propose that identification of respiratory virus during the diagnostic evaluation of febrile children with respiratory symptoms cannot be used as exclusive evidence against the diagnosis of KD. In one study without control subjects, the identification rate of respiratory viruses through multiplex reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR in children with KD was reported to be 22%4).

According to a recent retrospective study, patients with KD who harbor respiratory viruses have a higher frequency of coronary artery dilatation and are more often diagnosed with incomplete presentation of the disease5). If this is correct, identification of respiratory viruses should be considered to be a risk factor in children with KD.

We planned this study to survey the detection rate of respiratory viruses in children with KD through RT-PCR using a prospective case-control study design and to investigate the clinical impact of the existence of respiratory viruses during the acute phase of KD.

Materials and methods

From October 2010 to June 2011, 69 patients in the acute phase of KD were admitted to the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. We collected nasopharyngeal swab samples from 55 of these patients. Parents of the remaining 14 patients refused participation. Among 55 subjects, 48 (87.3%) fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for KD6), and 7 (12.7%) were diagnosed with incomplete KD. Diagnostic criteria of KD were fever, defined as body temperature above than 38℃ persisting ≥5 days, and a presence of ≥4 principal features-changes in extremities, polymorphous exanthema, bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection without exudates, changes in lips and oral cavity, and cervical lymphadenopathy (≥1.5 cm diameter)6). Fever duration of 3 or 4 days was permitted on establishing a diagnosis. An incomplete KD was diagnosed in a case with persisting fever and 2 or 3 principal features but without alternative diagnosis. Refractory cases are those in which fever persisted or recurred after 36 hours of initial infusion of immunoglobulin. We recruited 3 age-matched healthy control subjects from a day nursery and a kindergarten for every 2 children with KD within 1 month of the recruitment of patients. Children who have had a fever with respiratory symptoms within the previous month were excluded from the control group. A presentation of significant symptom usually from the respiratory tract infection-rhinorrhea, cough, or sputum was defined as respiratory symptom. Nine of the children with KD were matched with only one control subject due to failure of recruitment (in 7 cases) and loss of samples during processing (in 2 cases). A final group of 78 control subjects were recruited, and samples of nasopharyngeal swab were collected from them. The patients were subdivided into RT-PCR positive and negative groups. Clinical and echocardiographic data during the acute phase of illness were surveyed by review of the medical records. Coronary artery dilatation was defined according to the recommendation by Japanese Ministry of Health7).

We obtained informed consent from the parents of all 133 subjects, and the Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, approved this study (2010-0467).

Nasopharyngeal swabs were taken by flocked swab and were submitted in Universal Transport Medium (COPAN, Brescia, Italy). Viral RNA was extracted from the swabs with NucliSENS easyMAG (Biomerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). cDNA was synthesized using a Revert Aid First Standard cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas, York, UK), and each cDNA preparation was subjected to three sets of multiplex PCR with an RV15 ACE Detection kit (Seegene, Seoul, Korea). The RV15 ACE Detection kit targets 15 respiratory viruses, including respiratory syncytial viruses A and B, adenovirus, rhinovirus, parainfluenza viruses 1 to 4, influenza viruses A and B, metapneumovirus, bocavirus, corona viruses OC43/229E and NL63, and enterovirus. This set of 15 respiratory viruses corresponds exactly to the set of viruses causing respiratory infections in Korea that is monitored weekly by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention8).

Diameters of coronary arteries were converted to Z scores by using previously published regression equations9). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS ver. 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The median value with interquartile range was used to summarize data. Numerical variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, and Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables.

Results

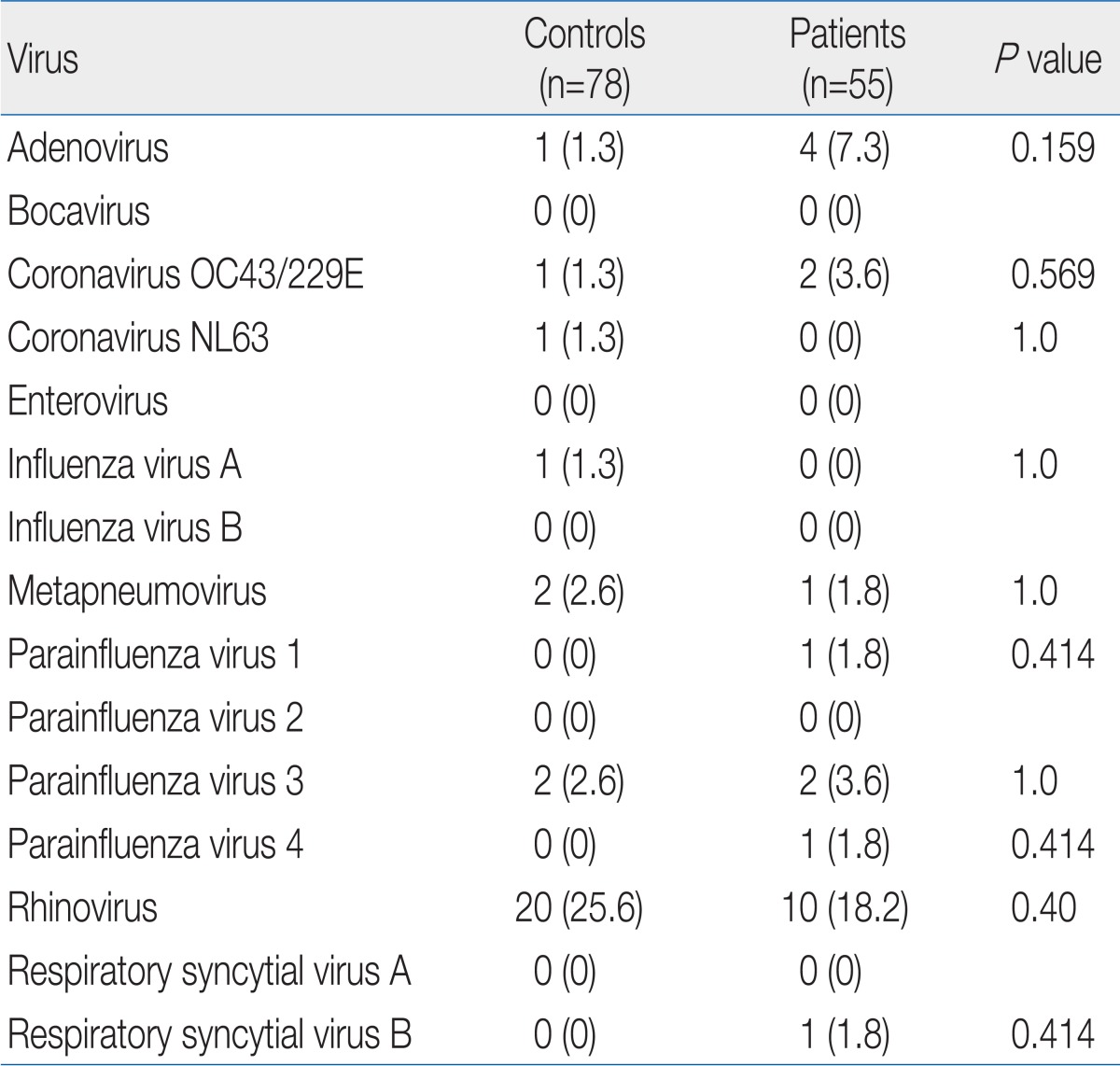

Median age of patients and controls was 2.77 years (range, 1.20 to 4.12 years) and 3.95 years (range, 2.15 to 4.46) respectively. There were 24 females (43.6%) in patient group and 43 (55.1%) in control group. The age was higher in controls than in patients (P=0.028), and the gender distribution was not different between groups (P=0.330). A total of 42 subjects were found to be infected with one or more of 10 different viruses by multiplex RT-PCR (Table 1). The detection rates in KD patients and controls were 32.7% (18/55 patients) and 30.8% (24/78 controls), respectively. More than 2 viruses were detected in 2 controls and 3 patients. Most frequently detected virus was rhinovirus, 10 in patient group and 20 in control group. However, there was no significant difference in the virus detection rate between the two groups (P=0.811), and no virus was significantly associated with KD.

Table 1.

Results of the Multiplex Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

Values are presented as no. of patients with relevant virus (%).

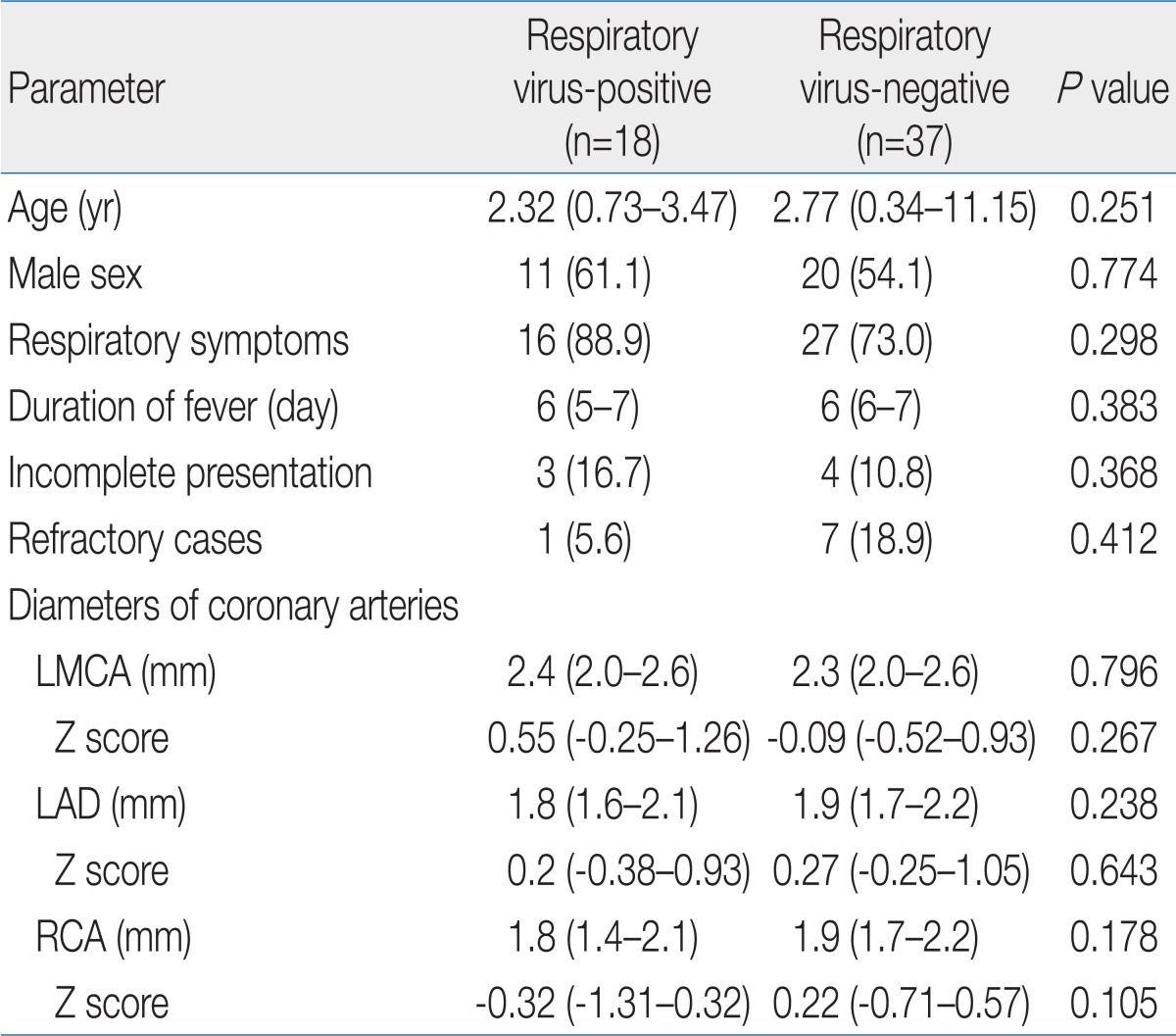

Comparison between the 18 patients with positive RT-PCR and the 37 patients with negative RT-PCR revealed no significant differences with respect to clinical findings (Table 2), including the prevalence of incomplete presentation of disease (P=0.368) and coronary artery diameters (P>0.05 of all coronary arteries). Coronary artery dilatation was detected in 5 patients (1 in RT-PCR positive group, P=1.0). Positive RT-RCR was not related to the existence of respiratory symptoms, because of no difference of the frequency of respiratory symptoms between 2 subgroups.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Two Patient Subgroups

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

LMCA, left main coronary artery; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

Discussion

Since the first report by Kawasaki10) in 1967, the etiology of KD has remained unknown. Rowley et al.11,12) detected an antigen with synthetic immunoglobulin A antibodies in formalin-fixed ciliated bronchial epithelium from patients with acute KD, and they suggested that the cytoplasmic inclusion bodies containing the antigen are consistent with aggregates of viral protein and nucleic acid. This hypothesis that KD may be triggered by a respiratory virus is attractive because respiratory symptoms are frequently observed during the acute phase of KD. However, no virus has been confirmed as a causative microorganism13). The 15 currently epidemic respiratory viruses tested in this study also showed no significant association with KD.

The detection rate for respiratory viruses in KD patients was 32.7%, which was not different from 30.8% in control subjects. It is obvious that identification of a respiratory virus through RT-PCR during the diagnostic evaluation of febrile children with respiratory symptoms cannot be used as exclusive evidence against the diagnosis of KD.

The existence of respiratory symptoms was not related to the result of RT-PCR in patients. We assumed 2 possibilities, first that a new unknown virus triggers a KD and respiratory symptoms, and second that respiratory symptoms in KD are the result of a vasculitis of respiratory tracts.

Jordan-Villegas et al.5) have suggested that patients with KD who harbor respiratory viruses have a higher frequency of coronary artery dilatation and are more often diagnosed with incomplete presentation of the disease. However, our results comparing the subgroups of patients divided on results of RT-PCR are inconsistent with their suggestions. Since our study was prospectively performed, there was less possibility of an association of incomplete disease presentation with more frequent virus tests. We believe that there may be no possibility that viruses without a causative role in KD have an impact on the clinical features.

Our study has limitations of the constitution of control group. The target ratio of patients to controls was 1.5:1, as in a previous study by others for the investigation of viruses in KD patients14). However, we failed to recruit control subjects and process samples on several occasions, with the result that the ratio of patients to controls was slightly less than 1.5:1. Additionally, the age was higher in controls, although we think that it was not so critical. Age range of controls also was in high prevalent age range of KD. The children were at the age before entrance into elementary school.

In conclusion, a positive RT-PCR for currently epidemic respiratory viruses should not be used as an evidence against the diagnosis of KD. These viruses were not associated with the incomplete presentation of KD and coronary artery dilatation.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from the Asan Institute of Life Sciences (subject number: 2010-508).

References

- 1.Bell DM, Brink EW, Nitzkin JL, Hall CB, Wulff H, Berkowitz ID, et al. Kawasaki syndrome: description of two outbreaks in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:1568–1575. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198106253042603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treadwell TA, Maddox RA, Holman RC, Belay ED, Shahriari A, Anderson MS, et al. Investigation of Kawasaki syndrome risk factors in Colorado. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:976–978. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200210000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raymond F, Carbonneau J, Boucher N, Robitaille L, Boisvert S, Wu WK, et al. Comparison of automated microarray detection with real-time PCR assays for detection of respiratory viruses in specimens obtained from children. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:743–750. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01297-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho EY, Eun BW, Kim NH, Lee J, Choi EH, Lee HJ, et al. Association between Kawasaki disease and acute respiratory viral infections. Korean J Pediatr. 2009;52:1241–1248. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan-Villegas A, Chang ML, Ramilo O, Mejias A. Concomitant respiratory viral infections in children with Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:770–772. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181dba70b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, Gewitz MH, Tani LY, Burns JC, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1708–1733. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Japan Kawasaki Disease Research Committee. Report of subcommittee on standardization of diagnostic criteria and reporting of coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. Tokyo: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acute infectious agents laboratory surveillance reports [Internet] Cheongwon: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; c2012. [2012 Feb 1]. Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu JJ, Cho SK, Park YM, Lee R, Chung S, Bae SH. Coronary artery diameter of normal children aged 3 months to 6 years. Korean J Pediatr. 2008;51:629–633. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawasaki T. Acute febrile mucocutaneous syndrome with lymphoid involvement with specific desquamation of the fingers and toes in children. Arerugi. 1967;16:178–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowley AH. Finding the cause of Kawasaki disease: a pediatric infectious diseases research priority. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1635–1637. doi: 10.1086/509514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowley AH, Baker SC, Shulman ST, Fox LM, Takahashi K, Garcia FL, et al. Cytoplasmic inclusion bodies are detected by synthetic antibody in ciliated bronchial epithelium during acute Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1757–1766. doi: 10.1086/497171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowley AH, Baker SC, Shulman ST, Rand KH, Tretiakova MS, Perlman EJ, et al. Ultrastructural, immunofluorescence, and RNA evidence support the hypothesis of a "new" virus associated with Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1021–1030. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehmann C, Klar R, Lindner J, Lindner P, Wolf H, Gerling S. Kawasaki disease lacks association with human coronavirus NL63 and human bocavirus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:553–554. doi: 10.1097/inf.0b013e31819f41b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]