Abstract

Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome (PMDS) is a rare syndrome and sometimes the cause of a common problem in paediatric and surgical practice, namely undescended testes. PMDS is a recessive disease in which there is a defect in anti-Mullerian hormone secretion or receptor activity resulting in persistence of Mullerian structures such as a uterus or fallopian tubes with otherwise normal virilisation. Here the authors present a case of a 1½-year-old boy who was referred to their hospital because of unilateral cryptorchidism. During laparoscopic surgery, two gonads were present joined together by a uterus-like structure. Additional investigations showed a normal male karyotype and biopsies of the gonads revealed infantile testis parenchyma making the diagnosis PMDS likely.

Background

Unilateral cryptorchidism is a frequently seen condition in paediatric and surgical practice; in most cases without any underlying pathology.1 Only rarely the underlying disorder is persistent Mullerian duct syndrome (PMDS).2 It is however important to recognise and determine the definite diagnosis of PMDS, which may decrease future medical and social problems for the patient.

Case presentation

A 1½-year-old boy was referred to our hospital with unilateral left-sided cryptorchidism. He was born at term after an uncomplicated pregnancy and no perinatal complications occurred. Physical examination postpartum revealed a non-palpable testis on the left side with normal male genitalia. At that time an ultrasound demonstrated that both testes were localised in the scrotum. During follow-up the left testis remained variable palpable and impalpable. Other than the unilateral cryptorchidism, the boy was healthy and had a normal development. Family and social history revealed no remarkable insights. Physical examination at presentation revealed an impalpable gonad on the left side with otherwise normal masculine external genitalia and normal penile length.

Investigations

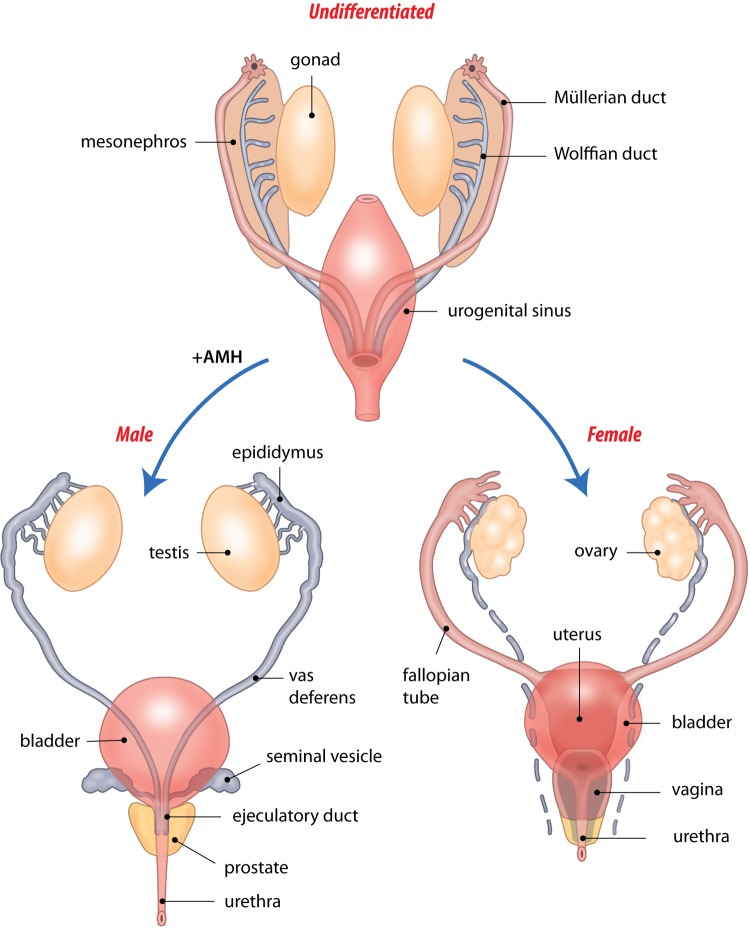

An ultrasound showed a normal descended and size testis on the right side; on the left, no testis could be visualised in the scrotum or inguinal region. Thus, a diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. During this procedure we found that there were two gonads present, joined together by a uterus-like structure (figure 1A, B, video 1). Blood was obtained as well as biopsies from the left gonad.

Figure 1.

(A, B) During laparoscopy the gonads where found to be joined together by a uterus-like structure (middle of the picture, one of the gonads is shown at the right side).

A video was made during surgery showing both of the gonads present and bound together by a uterus-like structure.

Treatment

Four months after diagnostic laparoscopy a laparotomy was performed. The right testis was found in the scrotum. In the right inguinal region, the left gonad was found as well as a uterus both herniated through an open processes vaginalis. Biopsies from the left gonad were obtained. Orchidopexy left was performed together with removing the top part of the uterus.

Outcome and follow-up

The obtained blood revealed a normal male karyotype (46XY) in all examined cells. Gonadal biopsies showed infantile testis parenchyma with no signs of ovarian differentiation, making the diagnoses PMDS likely. The AMH level was 313 ng/ml (age specific normal level 80–100 ng/ml) suggesting a defect in the AMH receptor.3 Screening for mutations on chromosome 12 and 19 was initialised with results pending. Due to the presence of normal external male genitalia and the results of the laboratory studies, no further discussion was initiated on gender assignment.

Discussion

Male sexual differentiation is a complex process including determination of the genetic sex, development of the gonads, and differentiation of the internal and external genital structures. Development of the gonads starts early after gestation. At approximately the 7th week of fetal life both Wolffian and Mullerian ducts are present, derived from the mesonephros. During the third month after gestation either the Wolffian or Mullerian duct becomes fully formed, while the other structure degenerates. In males, testosterone produced by the fetal testes causes the Wolffian duct to complete its development, which leads to the formation of the epididymis, seminiferous tubules and vas deference.

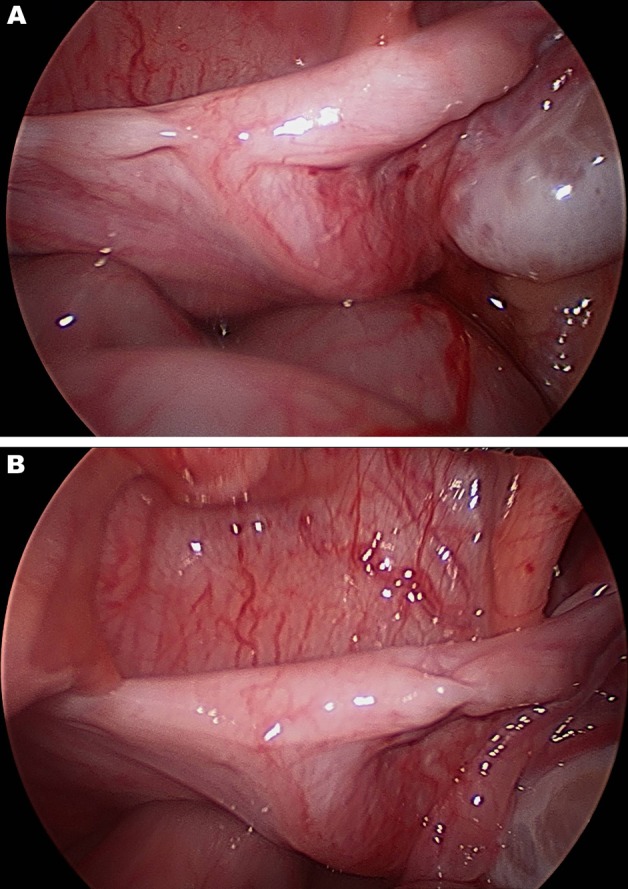

Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) secreted by the fetal Sertoli cells causes degeneration of the Mullerian ducts (figure 2).4–6 In cases of PMDS there is a defect in either AMH secretion or in the AMH receptor, which leads to a failure of normal regression of the Mullerian structures resulting in normal masculine virilisation with the presence of Mullerian derivates like a uterus or fallopian tubes.4 7

Figure 2.

During normal male sexual differentiation Mullerian structures regress under the influence of AMH. In patients with PMDS failure of normal regression of the Mullerian structures results in normal masculine virilisation with the presence of Mullerian derivates (picture by R. Slagter).

PMDS is transmitted in an autosomal recessive pattern. One research group performed large molecular studies among 82 families, which revealed a mutation in the AMH gene (located on chromosome 19) in 38 of the cases. In 33 families a defect in the AMH receptor gene (located on chromosome 12) was found and in the remaining 11 families the origin of PMDS could not be identified.7 8

Typically, patients present themselves during childhood either with bilateral cryptorchidism, unilateral cryptorchidism and inguinal hernia, or with transverse testicular ectopia in which one testis has descended dragging the Mullerian structures and sometimes the other testis with it. More commonly, PMDS is an accidental finding during evaluation of unexplained infertility or during abdominal surgery.9–16

Debate remains regarding the treatment of PMDS. Although there are just a few papers in literature reporting malignant transformation of remnant Mullerian structures, scrotal location allows follow-up of the testes by palpation.17 18 On the other hand, surgery imposes a risk for infertility and gonadal dysfunction. When surgery is chosen the literature, while limited, suggests it is best to perform laparoscopy as early as possible because of the beneficial effects on growth of undescended testes and the more accessible structures at younger age.19 20

The prognosis regarding fertility remains uncertain despite optimal treatment.

Learning points.

-

▶

Although rare, PMDS can be the cause of unilateral cryptorchidism.

-

▶

The endocrine mechanisms in PMDS can help us understand the normal sexual differentiation and development of the external genitalia.

-

▶

Debate remains regarding the treatment of PMDS but when surgery is performed it is important to do it as early as possible making the operation easier and potentially increasing the chances of fertility.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Barthold JS, González R. The epidemiology of congenital cryptorchidism, testicular ascent and orchiopexy. J Urol 2003;170:2396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Josso N, Belville C, di Clemente N, et al. AMH and AMH receptor defects in persistent müllerian duct syndrome. Hum Reprod Update 2005;11:351–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee MM, Misra M, Donahoe PK, et al. MIS/AMH in the assessment of cryptorchidism and intersex conditions. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2003;211:91–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.di Clemente N, Belville C. Anti-Müllerian hormone receptor defect. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;20:599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niewoehner CB. Endocrine Pathophysiology. Raleigh, N.C.: Hayes Barton Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kliegman R, Nelson WE. Nelson Textbook Of Pediatrics. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belville C, Van Vlijmen H, Ehrenfels C, et al. Mutations of the anti-mullerian hormone gene in patients with persistent mullerian duct syndrome: biosynthesis, secretion, and processing of the abnormal proteins and analysis using a three-dimensional model. Mol Endocrinol 2004;18:708–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belville C, Maréchal JD, Pennetier S, et al. Natural mutations of the anti-mullerian hormone type II receptor found in persistent mullerian duct syndrome affect ligand binding, signal transduction and cellular transport. Hum Mol Genet 2009;18:3002–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandli DW, Akbal C, Eugsster E, et al. Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome with bilateral abdominal testis: surgical approach and review of the literature. J Pediatr Urol 2005;1:423–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naouar S, Maazoun K, Sahnoun L, et al. Transverse testicular ectopia: a three-case report and review of the literature. Urology 2008;71:1070–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wuerstle M, Lesser T, Hurwitz R, et al. Persistent mullerian duct syndrome and transverse testicular ectopia: embryology, presentation, and management. J Pediatr Surg 2007;42:2116–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhapa E, Castagnetti M, Alaggio R, et al. Testicular fusion in a patient with transverse testicular ectopia and persistent mullerian duct syndrome. Urology 2010;76:62–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu TJ. The character of variant persistent müllerian-duct structures. Pediatr Surg Int 2002;18:455–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcus KA, Halbertsma FJ, Picard JY, et al. A visual pitfall: persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (PMDS). Acta Paediatr 2008;97:129–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaul A, Srivastava KN, Rehman SM, et al. Persistent müllerian duct syndrome with transverse testicular ectopia presenting as an incarcerated inguinal hernia. Hernia 2011;15:701–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demir O, Kizer O, Sen V, et al. Persistent mullerian duct syndrome in adult men diagnosed using laparoscopy. Urology 2011;78:566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinmura Y, Yokoi T, Tsutsui Y. A case of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the müllerian duct in persistent müllerian duct syndrome: the first reported case. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1231–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero FR, Fucs M, Castro MG, et al. Adenocarcinoma of persistent müllerian duct remnants: case report and differential diagnosis. Urology 2005;66:194–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandersteen DR, Chaumeton AK, Ireland K, et al. Surgical management of persistent müllerian duct syndrome. Urology 1997;49:941–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kollin C, Hesser U, Ritzén EM, et al. Testicular growth from birth to two years of age, and the effect of orchidopexy at age nine months: a randomized, controlled study. Acta Paediatr 2006;95:318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A video was made during surgery showing both of the gonads present and bound together by a uterus-like structure.