Abstract

Ionizing radiation can induce DNA damage and cell death by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS). The objective of this study was to investigate the radio-protective effect of catalpol (a main bioactive component in the traditional Chinese Rehmannia) on irradiated cells and mice. We found that treating cells with catalpol (25–100 μg/ml) before irradiation could significantly inhibit ionizing radiation (IR)-induced human lymphocyte AHH-1 cells apoptosis and increase cells viability in vitro. At the same time our study also showed that catalpol (25–100 mg/kg) reduced morphological damage of the gastrointestinal tract by 15.6%, 33.3% and 44.4%, respectively compared with the radiation-induced group, decreased plasma malondialdehyde (MDA) intestinal 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) levels and increased plasma endogenous antioxidants and peripheral white blood cells and platelets in vivo. These results suggest that catalpol possesses notable radio-protective activity, which might be related to its effect of reducing ROS.

Keywords: catalpol, radioprotection, apoptosis, reactive oxygen species

INTRODUCTION

Ionizing radiation is any electromagnetic wave or particle capable of producing ions. It can cause immediate chemical alterations in biological tissues that lead to cell damage or death. Radiation therapy is the treatment of choice for a majority of cancer patients. However, radio-protectors are needed to protect normal tissues when ionizing radiation is used to induce irreversible damage in nearby targeted cells. In addition to their importance for cancer treatment patients, radio-protectors are needed to protect other potentially exposed populations, such as workers in the nuclear power industry, space travelers or military personnel facing radiological terrorism from ionizing radiation. Because of their potential importance, researchers have put a great deal of effort into searching for radio-protectors.

Exposure to ionizing radiation (IR) can produce severe health impairments due to injury to and failure of susceptible organs. It has been reported that ionizing radiation generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that produce a marked effect in irradiation-induced cellular damage [1]. Excessive ROS lead to impaired intracellular ionic homeostasis by damaging cellular macromolecules, including DNA, protein and lipoid. Damaged DNA may lead to cell apoptosis or cancerization [2]. High concentrations of ROS can alter the balance of endogenous protective systems and damage mitochondria. Cytochrome c and calcium ions and other apoptosis-related factors may be released from damaged mitochondria into the cytosol following dysfunction of the mitochondrial membrane that regulates cell apoptosis [3, 4]. The gastrointestinal tract is one of the most susceptible organs to radiation [5]. As little as 1 Gy of radiation induces a dramatic increase in apoptosis in mouse small intestinal crypt within 3–6 h of exposure, predominantly in the stem cell region [6]. The hematologic system is also very sensitive to radiation. Exposure to ionizing radiation induces a dose-dependent decline in white blood cells and platelets [7].

Since irradiated cells produce damaging ROS, compounds with ROS scavenging characteristics may help to protect cells against irradiation-induced damage. Many traditional Chinese medicines have antioxidant characteristics, and most of them are non-toxic or have low toxicity at pharmacological doses, compared with most synthetic radio-protectors [8]. It is believed that screening and evaluating those herbal/plant products for developing effective radio-protectors has enormous potential.

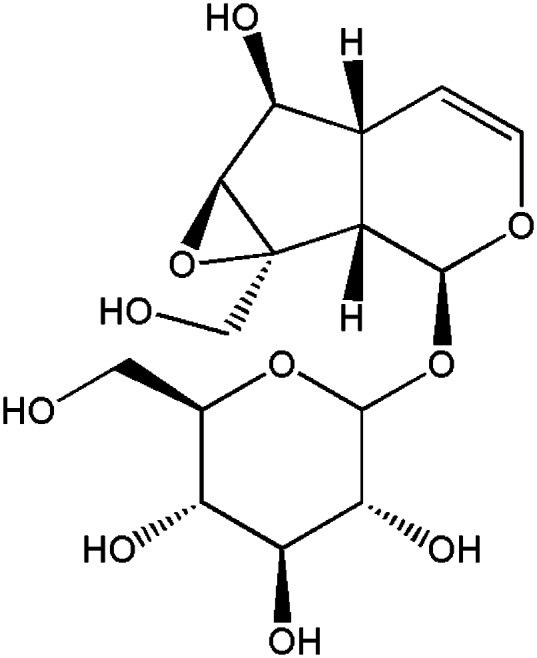

Catalpol (Fig. 1), an iridoid glucoside, is the principal bioactive component in the roots of Rehmannia glutinosa, a plant that is widely cultivated for its putative medicinal properties. Catalpol has been reported as an antioxidant, anti-apoptotic and immunoregulator and is the key constituent of Sisheng decoction, a blood-building medicine used in China for thousands of years that more recently has shown radio-protective effects in mice [9, 10]. This study focused on evaluating the protective effect of catalpol on irradiation-induced cell and mice which might be involved in ROS mechanisms.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of catalpol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Catalpol (purity >99%) was purchased from the Chinese National Institute for Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products (Beijing, China). Cell viability was determined by water-soluble tetrazolium (WST) assay using a cell counting kit (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). An annexin V-FITC-PI double-stained apoptosis detection kit was purchased from Biosea biotechnology Inc (Beijing, China). A DNA extractor kit was from Wako Chemical Inc (Osaka, Japan). Anti-8-OHdG antibody was purchased from Japan Institute for the Control of Aging (Fukuroi, Japan). Others chemicals were of domestic analytical reagent grade.

Cell culture and treatment

Human lymphocyte AHH-1 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, CA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified chamber. For radio-protective studies, cells were treated with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with or without catalpol, then the treated cells were immediately irradiated with γ-rays. After irradiation, the cells were used in the following experiments.

Irradiation

60Co-gamma rays in the irradiation centre (Faculty of Naval Medicine, Second Military Medical University, China) were used for irradiation purposes. Mice and cells (with or without catalpol pre-treatment) were exposed to different doses of radiation, depending upon the requirement of the present study. The dose rate of 60Co-gamma rays was 1 Gy/min.

Cell viability analyses

Human lymphocyte AHH-1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and pre-treated with or without catalpol, the treated cells were then immediately irradiated. After 4 Gy irradiation the cells were further cultured for 48 h [11]. Cell viability was determined by WST assay using a cell counting kit.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage assay was carried out using a LDH cytotoxicity detection kit (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech. Co. Ltd, China) according to the protocol in the user's manual. AHH-1cells were pre-treated with different doses of catalpol. Immediately, the cells were exposed to γ radiation and then transported to a 37°C water bucket. After a 4-h time period we analyzed the content of LDH in the cell suspension.

Apoptosis

Cells were suspended in 200 μl ice-cold binding buffer, and 10 µl fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled Annexin V and 5 μl propidium iodide (PI) were added. The cell suspension was gently mixed and incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature. Apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry (FCM, FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson Company). In the study Annexin V positive and PI negative cells were defined as apoptotic cells. Both Annexin V-FITC and PI negative cells were considered as viable cells, while both Annexin V-FITC and PI positive cells were considered as late apoptotic or already dead cells.

Mice and treatment

All the protocols were approved by the Second Military Medical University, China in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US NIH (publication No. 96-01). Male BALB/c mice weighing 21–23 g were used in the experiments. The animals were housed in individual cages in a temperature-controlled room with a 12-h light/dark cycle and food and water were provided ad libitum. For experiments, mice were treated intraperitoneally (IP) with or without different dose of catalpol 20 min before radiation. Mice were irradiated in a holder designed to immobilize unanesthetized mice such that the abdomens were presented to the beam.

Morphological observation

Mice were treated IP with or without catalpol 20 min before irradiation. Twelve hours after 8 Gy irradiation [12], mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under isoflurane anesthesia. A 5-cm segment of small intestine which was removed at 5 cm proximal to the terminal ileum was fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde-saline. Three 1-cm segments of intestinal specimen were embedded in paraffin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Morphological damages were assessed using the Chiu histological injury scoring system of intestinal villi (0 = normal mucosa, 1 = slight, 2 = moderate, 3 = massive subepithelial detachments, 4 = denuded villi, 5 = ulceration) [13]. Two independent and blinded researchers performed the histological scoring.

Biochemical assays

Arterial blood samples (0.6 ml) of mice were collected 12 h after irradiation. These samples were immediately centrifuged at 2500 rpm and 4°C for 10 min. The plasma was taken for biochemical estimations (SOD, GSH and MDA). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was assayed using the method of Kakkar et al. [14] based on the inhibition of the formation of the NADHPMS-NBT complex. The GSH concentration was measured using the method of Ellman [15]. This method was based on the development of a yellow color when 5′,5′-dithiobis 2-nitrobenzoic acid was added to compounds containing sulphydryl groups. MDA was assessed spectrophotometrically with the method defined by Ohkawa et al. [16] as MDA reacted with thiobarbituric acid and formed a pink, maximum absorbent complex at 532 nm wavelengths.

For determination of 8-OHdG levels in DNA from the intestine of mice, DNA was extracted from the mice intestinal specimen with a DNA extractor kit according to the method of Nakae et al. [17]. Then the isolated DNA was digested using the method of Valls-Belles et al. [18]. The 8-OHdG levels of these samples were measured as described by Inoue et al. [19]. Briefly, the samples were added to plate wells pre-coated with mouse monoclonal anti-8-OHdG antibody, of which the specificity has been proved by Toyokuni et al. [20]. They were incubated for 45 min at 37°C. After being washed three times, the wells were sequentially treated with Biotinylated rabbit-anti-mouse IgG for 30 min at 37°C and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for 30 min at 37°C. A substrate containing 3,3,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was added and the wells were incubated for 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of sulphuric acid. The absorbance was read at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Hematological examinations

Blood samples of mice were collected from the fossa orbitalis 3 days after irradiation. A Sysmex-820 auto cell counting machine was used to analyze white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM for each experiment. The number of samples is indicated in the description of each experiment. Statistical analysis was performed by using a one way Analysis of Variance. Between groups, variance was determined using the Student–Newman–Keuls post-hoc test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

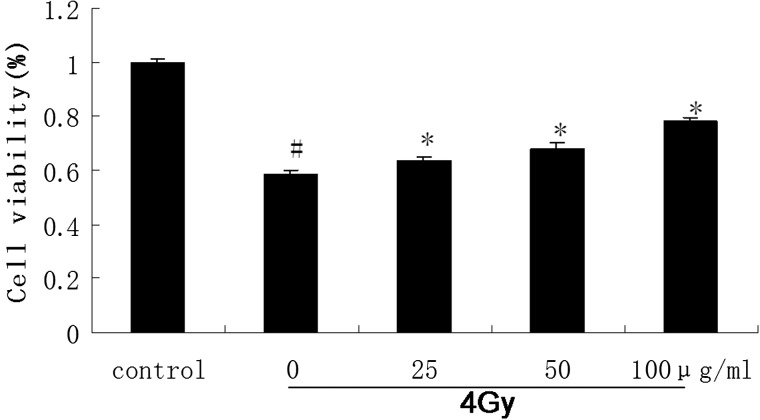

Effect of catalpol on viability in irradiated AHH-1 cells

To study the radio-protective effects of catalpol in cell culture, we examined the viability of irradiated AHH-1 cells. Cells treated with or without different concentrations of catalpol were exposed to 4 Gy of γ-radiation as described in the Methods section. We demonstrated that pre-treatment of AHH-1 cells with 25–100 μg/ml catalpol before irradiation significantly increased cell survival as compared with cells treated with radiation alone (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The AHH-1 cells pretreated with or without various concentrations of catalpol (25–100 μg/ml) were exposed to 4 Gy 60Co γ-ray irradiation.

Cell viabilities were evaluated by WST assay 48 h after irradiation and relative absorbance were compared. The control cell was considered 100% viable (#P < 0.05 compared with the value of control *P < 0.05 compared with the value with 4 Gy irradiation alone).

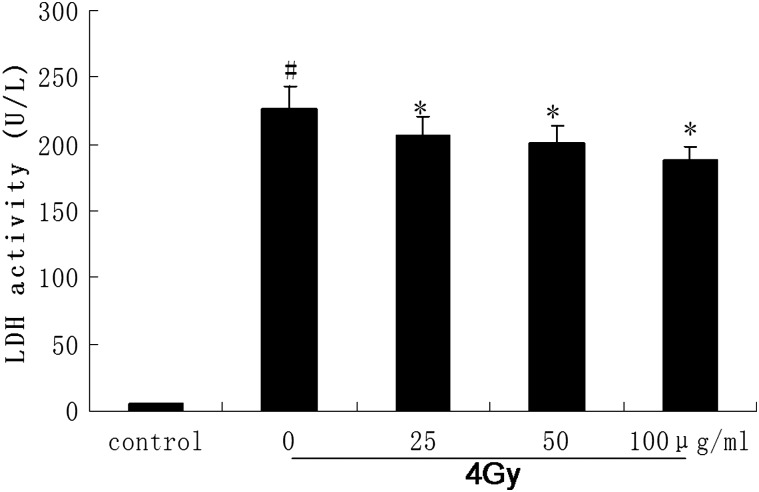

Effect of catalpol on cellular lactatedehydrogenase (LDH) leakage in irradiated cells

Besides the cell viability, we also determined LDH activities to estimate cellular LDH leakage from damaged cells. The result indicated that pre-treatment with different doses of catalpol before irradiation significantly decreased LDH leakage of AHH-1 cells that were exposed to 4 Gy γ-radiation (Fig. 3). This result was consistent with the result obtained by cell viability observation.

Fig. 3.

Changes in the levels of LDH in the AHH-1 cells pretreated with or without various concentrations of catalpol (25–100g/ml) which were exposed to 4 Gy 60Co γ-ray irradiation.

Levels of LDH were evaluated with a LDH kit 48 h after irradiation. The control cell was not exposed to γ-ray irradiation (#P < 0.05 compared with the value of the control; *P < 0.05 compared with the value with 4 Gy irradiation alone).

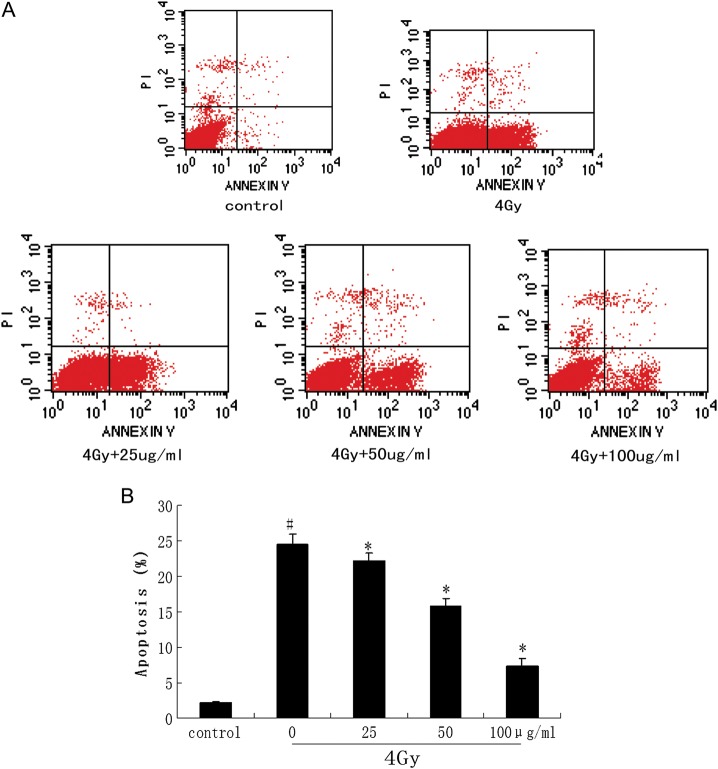

Effect of catalpol on apoptosis in irradiated AHH-1 cells

To determine the radiation-induced apoptosis of irradiated AHH-1 cells, we analyzed treated cells by using Annexin V-FITC and PI staining in flow cytometry assay. It indicated that 4 Gy irradiation caused lower rates of apoptotic cells on catalpol pretreated (25–100 μg/ml) than non-pretreated AHH-1 cells. The detail is showed in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

inhibitory effect of Catalpol on 60Coγ-ray irradiation-induced cell apoptosis.

AHH-1 cells were pretreated with or without different concentrations of (25–100 μg/ml) prior to 4 Gy irradiation. Cells were harvested and apoptosis was confirmed by FCM (staining with both Annexin V-FITC and PI) 6 h later (A). The percentages of apoptotic cells were compared (#P < 0.05 compared with the value of control; *P < 0.05 compared with the value with 4 Gy irradiation alone) (B).

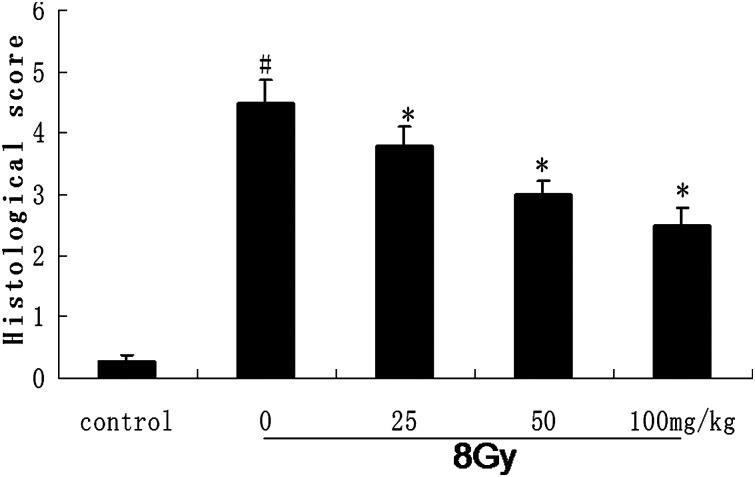

Effect of catalpol on irradiated intestinal injury in vivo

We observed histological IR injuries characterized by shortening of the villi, loss of villous epithelium and prominent mucosal neutrophil infiltration. All of these changes were ameliorated by administration of catalpol. Chiu scoring and microphotographs are shown in Fig. 5. As shown in Fig. 5, catalpol administration significantly reduced the mucosal injury caused by IR.

Fig. 5.

Morphologic observation of the intestinal tissue in normal, γ-irradiated and different doses of catalpol pre-treated mice.

Photomicrographs of the intestinal tissue stained by the hematoxylin and eosin 12 h after radiation. Intestinal mucosal injury evaluated by Chiu scoring system. Grading as follows (0 = normal mucosa, 1 = slight, 2 = moderate, 3 = massive subepithelial detachments, 4 = denuded villi, 5 = ulceration). Data are expressed as means ± SEM for at least triplicate independent experiments (n = 8 per group). #P < 0.05 compared with the value of control; *P < 0.05 compared with the value with 8 Gy irradiation alone.

Changes in the activities of plasma SOD, GSH and MDA

The plasma SOD, GSH and MDA concentrations were measured after 12 h of irradiation (Table 1). Plasma SOD and GSH concentrations at 12 h of irradiation at different doses of catalpol were significantly higher than in the irradiated alone group.In addition, plasma MDA were significantly lower than in the irradiated alone group.

Table 1.

Changes in the activities of plasma SOD, GSH and MDA

| Grouping (n = 8) | SOD (U/mg pro) | GSH (mg/ml) | MDA (nmol/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 11.78 ± 0.99 | 0.68 ± 0.02 | 0.78 ± 0.60 |

| 8 Gy | 7.62 ± 0.67# | 0.36 ± 0.01# | 6.81 ± 0.2# |

| 8 Gy + 25 mg/kg | 8.80 ± 0.90* | 0.40 ± 0.02* | 5.34 ± 0.11* |

| 8 Gy + 50 mg/kg | 8.95 ± 0.56* | 0.50 ± 0.03* | 4.79 ± 0.12* |

| 8 Gy + 100 mg/kg | 10.06 ± 0.61* | 0.61 ± 0.02* | 4.13 ± 0.13* |

The mice pretreated with or without various concentrations of catalpol (25–100 mg/kg) were exposed to 8 Gy 60Co γ-ray irradiation. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 8). #P < 0.05 compared with the value of control; *P < 0.05 compared with the value with 8 Gy irradiation alone.

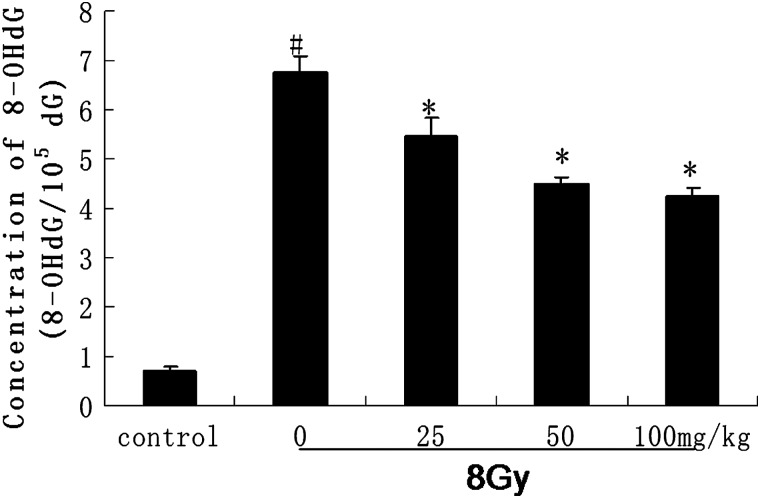

Changes in the levels of intestinal 8-OHdG

The intestinal 8-OHdG concentrations were measured after12 h of irradiation (Fig. 6). Intestinal 8-OHdG concentrations at 12 h of irradiation in different dosage groups were significantly lower than of theirradiated alone group.

Fig. 6.

Oxidative DNA damage was assessed by 8-OHdG immunoreactivity.

Intestinal 8-OHdG concentrations in normal, γ-irradiated and catalpol pre-treated groups 12 h after irradiation are shown. Relative to the irradiation alone group, catalpol significantly decreased the concentration of 8-OHdG. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 8), #P < 0.05 compared with the value of control; *P < 0.05 compared with the value with 8 Gy irradiation alone.

Changes in hematology

Peripheral white blood cells and platelets were decreased 3 days after 8 Gy radiation. While, the peripheral red blood cells had no change. The concentrations of peripheral white blood cells and platelets in different catalpol dosage groups were significantly higher than in the irradiated alone group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in peripheral blood cells and platelets

| Grouping (n = 8) | White blood cells (×1010/l) | Red blood cells (×1012/l) | Platelets (×1010/l) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10.32 ± 2.03 | 8.01 ± 0.76 | 793.62 ± 206.31 |

| 8 Gy | 2.02 ± 0.63# | 7.95 ± 0.51 | 178.53 ± 185.42# |

| 8 Gy + 25 mg/kg | 3.54 ± 0.77* | 7.67 ± 1.04 | 405.31 ± 143.38* |

| 8 Gy + 50 mg/kg | 4.62 ± 0.71* | 7.92 ± 1.10 | 498.54 ± 135.91* |

| 8 Gy + 100 mg/kg | 6.12 ± 1.32* | 8.12 ± 0.98 | 778.38 ± 223.04* |

The mice pretreated with or without various concentrations of catalpol (25–100 mg/kg) were exposed to 8 Gy 60Co γ-ray irradiation. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 8). #P < 0.05 compared with the value of control; *P < 0.05 compared with the value with 8 Gy irradiation alone.

DISCUSSION

The major finding of the present study is that pre-incubation of AHH-1 cells with catalpol markedly reduces the decrease in viability and apoptosis associated with exposure to 4 Gy radiation as determined by WST, LDH assay and flow cytometric analysis. At the same time our study also showed that catalpol can protect gastrointestinal endothelia from radiation-induced injury, decrease plasma MDA intestinal 8-OHdG levels and increase plasma endogenous antioxidants and peripheral white blood cells and platelets in vivo. These results suggested that catalpol possesses notable radio-protective activity, which might be related to its effect of reducing ROS.

Catalpol, an iridoid glucoside found in the root of R. glutinosa Libosch, has been shown to exhibit various biological and pharmacological activities, including anti-tumor [21], anti-inflammation [22], anti-oxidation [23–25] and anti-apoptosis activities [26, 27]. Exposure of ionizing radiation can lead to increased generation of ROS, including hydroxyl radicals (OH), superoxide anions (O2−), singlet oxygen (1O2) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which are major determinants of cellular damage including apoptosis and necrosis. Since most of the ionizing radiation-induced damage is caused by ROS, we speculate that the radio-protective effect of catalpol may result from its ROS scavenging effect.

Endogenous antioxidants are a group of substances that significantly inhibit or delay oxidative processes while being oxidized themselves [28]. Antioxidant enzymes are important in providing protection from radiation exposure [29]. Also, glutathione (GSH) participates non-enzymatically in protection against radiation damage [30]. Therefore, a reduction in the activity of these substances can result in a number of deleterious effects. Membrane lipids are the major targets of ROS and the free radical chain reaction [31]. The increase in the levels of lipid peroxidation products such as malondialdehyde and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances are the indices of lipid damage [1]. Also DNA is one of the major targets of ROS and 8-OHdG is formed from deoxyguanosine in DNA by hydroxyl free radicals [32]. In our study, we observed a significant decrease in the levels of enzymatic antioxidant (SOD), non-enzymatic antioxidant (GSH) and an increase in the levels of plasma MDA and intestinal 8-OHdG of irradiated mice. However, pre-treatment of catalpol prior to radiation exposure increased the antioxidant status at both enzymatic and non-enzymatic levels and decreased the levels of MDA and 8-OHdG. We may conclude that the protection in the antioxidant status during catalpol pre-treatment has further decreased the attack of free radicals, prevented DNA damage and decreased lipid peroxidation, thereby decreasing the deleterious effects of radiation.

Some radio-protectors, such as thiol compounds, have relatively high toxicity [33], while cytokines and immunomodulators should be used with low radiation doses or in combination with radical scavengers and antioxidants [34]. The sulphydryl compound amifostine, named WR-2721, which is the only radio-protectant registered for use in humans, has shown good radio-protective effects [35]. However, it has many side-effects limiting its clinical use such as hypertension, nausea, vomiting and others [36]. Natural antioxidants, such as flavonoids and others, have fewer toxic side-effects but also a high degree of protection. Therefore, catalpol could be used as a radiation protector in clinical radiotherapy, but also as a mitigator in the sense of its use in workers in the nuclear power industry, space travelers or military personnel facing radiological terrorism from ionizing radiation.

In conclusion, the effect of reducing ROS plays an important role in the radio-protective effects of catalpol. However, the exact mechanism and signaling pathway involved in the protection role of catalpol in ionizing radiation injury need to be studied in the future.

FUNDING

This study was supported by a grant from the National Science department of China (2008ZXJ09001-018) and Science department of Shanghai (05DZ19716).

REFERENCES

- 1.Dubner D, Gisone P, Jaitovich I, et al. Free radicals production and estimation of oxidative stress related to gamma irradiation. Biol Race Elem Res. 1995;47:265–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02790126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cadet J, Bellon S, Douki T, et al. Radiation-induced DNA damage: formation, measurement, and biochemical features. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2004;23:33–43. doi: 10.1615/jenvpathtoxoncol.v23.i1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogawa Y, Kobayashi T, Nishioka A, et al. Radiation-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation prior to oxidative DNA damage in human peripheral T cells. Int J Mol Med. 2003;11:149–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olive P-L. The role of DNA single and double strand breaks in cell killing by ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 1998;150:42–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramachandran A, Madesh M, Balasubramanian K-A. Apoptosis in the intestinal epithelium: its relevance in normal and pathophysiological conditions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:109–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potten C-S. Extreme sensitivity of some intestinal crypt cells to X and gamma irradiation. Nature. 1977;269:518–21. doi: 10.1038/269518a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dainiak N. Hematologic consequences of exposure to ionizing radiation. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:513–28. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss J-F, Landauer M-R. Protection against ionizing radiation by antioxidant nutrients and phytochemicals. Toxicology. 2003;189:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen X-Y, Wang L, Tian Y-P. Protective effect of Sisheng Decoction on radiation-induced injury of mice. Acad J PLA post Med School. 2010;9:921–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang S-F, Chen Z, Li B, et al. Effects of Sisheng Decoction on spontaneous activity and serum concentration of malondialdehyde in mice with yin deficiency syndrome. J Chin Integra Med. 2008;10:1029–33. doi: 10.3736/jcim20081008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chun R-L, Zhou Z, Zhu D, et al. Protective effect of paeoniflorin on irradiation-induced cell damage involved in modulation of reactive oxygen species and the mitogen-activated protein kinases. 2007;39:426–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.09.011. IJBCB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sang G-K, Seon Y-N, Choon W-K. In vivo radioprotective effects of oltipraz in γ-irradiated mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:1585–90. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00669-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu C-J, McArdle A-H, Brown R, et al. Intestinal mucosal lesion in low-flow states. I. A morphological, hemodynamic, and metabolic reappraisal. Arch Surg. 1970;101:478–83. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1970.01340280030009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakkar P, Das B, Viswanathan P-N. A modified spectrophoto-metric assay of superoxide dismutase (SOD) Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1984;21:130–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellman G-L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95:351–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakae D, Kobayashi Y, Akai H, et al. Involvement of 8-hydrox-yguanine formation in the initiation of rat liver carcinogenesis by low dose levels of N-nitrosodiethylamine. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1281–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Victoria V-B, Torres M-C, Boix L, et al. α-Tocopherol, MDA-HNE and 8-OHdG levels in liver and heart mitochondria of adriamycin-treated rats fed with alcohol-free beer. Toxicology. 2008;249:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue T, Hayashi M, Takayanagi K, et al. Oxidative DNA damage is induced by chronic cigarette smoking, but repaired by abstention. J Health Sci. 2003;51:169–172. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyokuni S, Tanaka T, Hattori Y, et al. Quantitative immunohistochemical determination of 8-hydroxy-2′deoxyguanosine by a monoclonal antibody N45.1: Its application to ferric nitrilotriacetate-induced renal carcinogenesis model. Lab Invest. 1997;76:365–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pungitore C-R, León L-G, García C, et al. Novel antiproliferative analogs of the Taq DNA polymerase inhibitor catalpol. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:1332–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim H-M, An C-S, Jung K-Y, et al. Rehmannia glutinosa inhibits tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 secretion from mouse astrocytes. Pharmacol Res. 1999;40:171–6. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bi J, Jiang B, Liu J-H, et al. Protective effects of catalpol against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in astrocytes primary cultures. Neurosci Lett. 2008;442:224–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao Y-R, Jiang L, Duan Y-L, et al. Efficacy of catalpol as protectant against oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction on rotenone-induced toxicity in mice brain. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;23:314–18. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X-L, Zhang A, Jiang B, et al. Further pharmacological evidence of the neuroprotective effect of catalpol from Rehmannia glutinosa. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:484–90. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang B, Liu J-H, Bao Y-M, et al. Catalpol inhibits apoptosis in hydrogen peroxide-induced PC12 cells by preventing cytochrome c release and inactivating of caspase cascade. Toxicon. 2004;43:53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li D-Q, Bao Y-M, Li Y, et al. Catalpol modulates the expressions of Bcl-2 and Bax and attenuates apoptosis in gerbils after ischemic injury. Brain Res. 2006;1115:179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalpana K-B, Devipriya N, Srinivasan M. Investigation of the radioprotective efficacy of hesperidin against gamma radiation induced cellular damage in cultured human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 2009;676:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Nahas S-M, Mattar R-E, Mohamed A-A. Radioprotective effect of vitamins C and E. Mutat Res. 1993;301:143–7. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(93)90037-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimomura Kojima S, Matsumori S. Effect of pre-irradiation with low dose γ-rays on chemically induced hepatotoxicity and glutathione depletion. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:1583–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandey B-N, Mishra K-P. Fluorescence and ESR studies on membrane oxidative damage by γ-radiation. Appl Magn Reson. 2000;18:483–92. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasai H. Analysis of a form of oxidative DNA damage, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, as a marker of cellular oxidative stress during carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1997;387:147–63. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(97)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hosseinimehr S-J. Trends in the development of radioprotective agents. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:794–805. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herodin F, Drouet M. Cytokine-based treatment of accidentally irradiated victims and new approaches. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:1071–108. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gosselin T-K, Mautner B. Amifostine as a radioprotectant. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6:175–6. doi: 10.1188/02.CJON.175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genvresse I, Lange C, Schanz J, et al. Tolerability of the cytoprotective agent amifostine in elderly patients receiving chemotherapy: a comparative study. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;12:345–9. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]