Abstract

Purpose

Abdominal intensity-modulated radiation therapy and proton therapy require quantification of target and organ motion to optimize localization and treatment. Although addressed in adults, there is no available literature on this issue in pediatric patients. We assessed physiologic renal motion in pediatric patients.

Methods and Materials

Twenty free-breathing pediatric patients at a median age of 8 years (range, 2-18 years) with intra-abdominal tumors underwent computed tomography (CT) simulation and 4-dimensional CT (4DCT) acquisition (slice thickness, 3 mm). Kidneys and diaphragms were contoured during 8 phases of respiration to estimate center of mass motion. We quantified center of kidney mass mobility vectors in 3 dimensions: anterior-posterior (A-P), medial-lateral (M-L), and superior-inferior (S-I).

Results

Kidney motion decreases linearly with decreasing age and height. The 95% confidence interval for the averaged minima and maxima of renal motion in children younger than 9 years was 5 to 9 mm in the M-L direction, 4 to 11 mm in the A-P direction, and 12 to 25 mm in the S-I dimension for both kidneys. In children older than 9 years, the same confidence interval reveals a widening range of motion that was 5 to 16 mm in the M-L direction, 6 to 17 mm in the A-P direction, and 21 to 52 mm in the S-I direction. Although not statistically significant, renal motion correlated with diaphragm motion in older patients. The correlation between diaphragm motion and BMI was borderline (r = 0.52, p = 0.0816) in younger patients.

Conclusions

Renal motion is age and height dependent. Measuring diaphragmatic motion alone does not reliably quantify pediatric renal motion. Renal motion in young children ranges from 5 to 25 mm in orientation-specific directions. The vectors of motion range from 5 to 52 mm in older children. These preliminary data represent novel analyses of pediatric intra-abdominal organ motion.

Keywords: pediatric, kidney, organ motion, abdominal tumors, 4D computed tomography

INTRODUCTION

The most commonly irradiated solid tumors in the abdomen of children include neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Abdominal irradiation is also used to treat Ewing sarcoma, nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft-tissue sarcoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, aplastic anemia, and acute leukemias under certain conditions. The kidneys are considered one of the primary radiation dose–limiting organ with an estimated risk of complication at 5 years of 5% when either the entire kidney is exposed to 23 Gy or one third of the organ receives 36 Gy1. Considering that many children receiving abdominal irradiation require doses that exceed the lower bound and that a complication risk of 5% is unacceptable in clinical practice, protecting this vital organ in the setting of positional uncertainty may lead to prioritizing renal sparing over target coverage. A recent report from the German Group of Pediatric Radiation Oncology indicates that the risk of renal impairment in current protocols is low; however, these investigators acknowledge that low toxicity in current pediatric trials may reflect the habit of radiation oncologists to respect renal tolerance; the possibility of compromising target coverage was not mentioned2.

Breathing is the primary physiologic process that affects abdominal organ motion and positional uncertainty. Other sources include gastrointestinal filling and peristalsis3, 4, the cardiac cycle5, medication-induced changes in organ dimensions6, vasculopathy7, vascular surgery including renal vessel stenting8, postoperative adhesions causing organ shift, and physiologic deformation of the tumor in response to treatment. Together, these sources define the margins that during the treatment-planning process should be added to organs at risk to minimize treatment-related side effects.

Limited information is available to define the required margins to compensate for physiologic variations in size, shape, and position of organs at risk during radiation therapy (RT) of pediatric abdominal tumors. Understanding organ motion and positional uncertainty in the abdomen during RT is crucial for achieving disease control and limiting long-term late effects. Knowledge of organ motion and position is also necessary to take full advantage of new precise-delivery and conformity methods in radiation oncology that are available to children, including intensity-modulated RT (IMRT), robotics-assisted hypofractionated RT, and proton therapy.

Renal motion and positional uncertainty may create a discrepancy between predicted and delivered treatment plans. To overcome this problem, data should be gathered in the setting of precise and individualized immobilization to model renal motion and its effect on implementing specific treatment protocol guidelines and newer delivery methods9-14. To this end, we used 4-dimensional computed tomography (4DCT) to quantify motion in individual kidneys of pediatric patients undergoing planning for abdominal RT. Our goal was to model renal motion by age and anthropomorphic measures including height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) and to correlate the motion of the diaphragm with that of the kidneys, because management of abdominal organ motion relies on respiratory gating. Because renal motion in adults is driven mainly by respiration15-17, we hypothesized that we would observe a similar finding in children and that the motion of the kidneys parallels that of the diaphragm when corrected for important clinical factors such as the use of anesthesia.

Although adult populations have been studied to quantify the effect of physiologic processes on abdominal organ motion, this report is the first to assess the appropriate margins for abdominal RT in a large cohort of pediatric patients. We expand the body of literature on abdominal RT in adults by quantifying these processes in pediatric patients. We also define intra-abdominal organ motion and supplement ICRU-62–compliant guidelines for this population. The kidneys are one of the primary radiation dose–limiting organs of interest in the abdomen. Reducing the dose to these structures while simultaneously delivering full-target doses to intra-abdominal tumors is crucial to pediatric RT and to the development of highly conformal irradiation methods using photons or protons. Using 4DCT, we quantified the motion track of the center of mass of individual kidneys in pediatric patients grouped based on age, height, weight, BMI, and diaphragmatic motion. Due to sedation requirements, coached breathing was not uniformly possible. Thus, this data set reflects renal motion parameters for uncoached, free-breathing patients throughout the age/developmental spectrum of the pediatric population.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients

We reviewed the 4DCT data of 20 consecutive patients who underwent planning for abdominal RT via 21 imaging studies; one patient required 2 4DCTs. The median age of the group was 8 years (range, 2-18 years) and included 10 boys and 10 girls. Tumor types included neuroblastoma (n=8), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=8), soft-tissue sarcoma (n=2), ganglioneuroblastoma (n=1), and Wilms tumor (n=1). This retrospective study was approved by the St. Jude Institutional Review Board.

4DCT Acquisition

We obtained 4DCT scans using a 24-detector CT simulator (Somatom Sensation Open, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). Images were acquired in the supine position and in spiral mode by using the following parameters: 400 effective mA, 120 kV, 0.5- to 1-s gantry rotation, 0.1 pitch, 1.2-mm collimation, and 3-mm slice thickness. A plastic body phantom of 32-cm diameter and 15-cm length was scanned using the same protocol and demonstrated a volume CT dose index (average absorbed dose per scan) of 33 mGy.

Each respiratory cycle was captured as a series of 8 traces, 4 inspiratory quarters and 4 expiratory quarters, acquired at equally spaced intervals between 0% and 100% during normal, uncoached breathing. Breathing-control methods were not used in any case due to the frequent need for intravenous general anesthesia using propofol; patients requiring anesthesia (n=10) did not require airway management and received only supplemental oxygenation via nasal cannulae. Patients requiring anesthesia were noted for purposes of analysis.

Respiratory trace measurements were obtained with the aid of an external abdominal excursion test. An elastic belt containing a load-sensitive pressure sensor was affixed to the abdominal/low-thoracic wall (Anzai Medical, Tokyo, Japan). The sensor was placed along the midclavicular line, approximately 5 to 10 cm inferior to the xiphoid process.

Data Processing

Absolute vectors of renal motion and diaphragmatic motion were determined for each of the 21 imaging datasets included in this study. Postprocessing of 4DCT images removed irregular traces or computer-generated virtual fiducials automatically set to mark the initiation of irregular patterns within breathing traces. The final amplitude-adjusted projections were exported to a workstation for fusion to the planning CT dataset, which was acquired immediately prior to the 4DCT. Simultaneously, copies of the dataset were submitted for contouring on a separate workstation. Each kidney was contoured individually on each of the 8 acquired traces. The traces were loaded to the Siemens InSpace image viewer and exported to software programmed to quantify renal motion based on whole-kidney contours for each of the 8 phases of respiration. The geometric center of mass was determined and used as the primary calculation reference point for organ motion vectors in the medial-lateral (M-L), anterior-posterior (A-P), and superior-inferior (S-I) coordinate planes.

The above parameters examined the absolute excursion of the center of mass of individual kidneys without reference to a baseline position. To obtain directional vectors in any given planar direction, an arbitrary baseline in 3-dimensional (3D) space at the 0 inspiration trace was established. Maximal positive and negative motion vectors were then established relative to this (0, 0, 0) set point in 3D-space within MATLAB. The observed directional motion was further assigned the appropriate trace through inspiration or expiration in which this maximal motion vector occurred.

Mean vectors in the M-L, A-P, and S-I directions were then associated with a 95% confidence interval and standard error. Images of each kidney were subdivided by the extent of motion from the preselected baseline position to derive these values.

Statistical Analyses

The linear regression model was used to investigate the relationship between dependent and independent variables. Dependent variables included measures of renal motion, while independent variables included age, weight, height, and diaphragmatic motion. The Fisher exact test was used to test the association between two categorical variables. The Pearson correlation was used to measure the correlations among independent variables with a significance level of 0.05 for the two-sided test.

RESULTS

Renal Motion Quantification

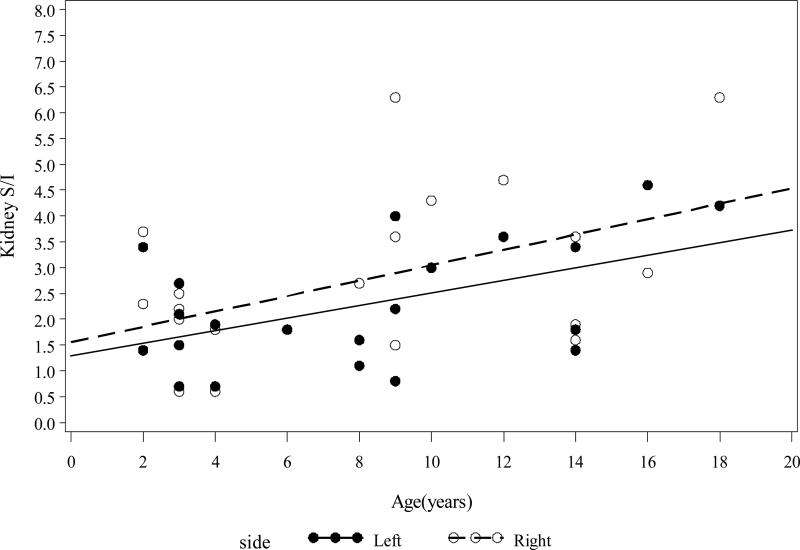

Age and diaphragmatic movement were highly correlated (r = 0.71, p = 0.0002) among the 20 pediatric patients included in our analysis. Renal motion correlated with age in the M-L and S-I directions. The amount of motion increased in the M-L direction by 0.039 ± 0.015 mm (left kidney, p = 0.0209) and 0.046 ± 0.016 mm (right kidney, p = 0.0115) for every yearly increase in the patients’ age. The amount of motion in the S-I direction increased by 0.121 ± 0.047 mm (left kidney, p = 0.0187) and 0.148 ± 0.064 mm (right kidney, p = 0.0323) for every yearly increase in the patients’ age (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Left and right kidney motion S/I by age

Renal motion in the M-L direction correlated with height. For every 1-cm increase in height, the left kidney's movement increased by 0.006 ± 0.002 mm (p = 0.017), and the right kidney moved 0.006 ± 0.003 mm (p = 0.042) (data not shown).

Correlations between renal motion and diaphragmatic motion differed based on which side of the body the kidney was located. Specifically, for every 1-mm increase in diaphragmatic movement, the right kidney moved 0.86 ± 0.22 mm (p = 0.0009) in the M-L direction and 3.36 ± 0.78 mm (p = 0.0004) in the S-I direction. However with a 1-mm increase in diaphragmatic movement, the left kidney moved 1.95 ± 0.66 mm (p = 0.0085) in the S-I direction (Figure 2) only; no significant movement occurred in the M-L dimension.

Figure 2.

Left and right kidney motion S/I by diaphragm motion

Factors Affecting Renal Motion

When the correlation between renal motion and diaphragmatic motion was adjusted for sex, the correlations between the 2 measures persisted; however, we found no significant difference in renal motion on the basis of sex. Similarly, when the model included an interaction between diaphragmatic movement and sex, we found no significant relationship.

Due to age-stratified absolute motion vector differences, the patients were divided into 2 age groups; the younger age group (2-8 years) included 11 children, and the older group (9-18 years) included 9 patients. The use of anesthesia and patient age were highly correlated (p = 0.0075). The younger age group included 11 children who required anesthesia, whereas the older group included only one. One 2-year-old child who required anesthesia also required a second 4DCT; no other subject required repeated imaging to assess interfractional changes in motion. Descriptive statistics for renal and diaphragmatic motion by age are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Renal Motion in Pediatric Patients Grouped by Age

| Pt. Group | n | Variable | Mean | SD | Med | Min | Max | Lower 95%CL* | Upper 95% CL* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young (2-8 y) | 11 | Age (y) | 4.08 | 2.11 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 8.00 | 2.74 | 5.42 |

| Height (cm) | 101.91 | 20.52 | 97.00 | 79.00 | 152.10 | 88.87 | 114.94 | ||

| Movement (mm): | |||||||||

| Diaphragm | 5.08 | 1.88 | 4.50 | 3.00 | 10.00 | 3.89 | 6.28 | ||

| R kidney M-L | 0.69 | 0.23 | 0.70 | 0.40 | 1.20 | 0.54 | 0.85 | ||

| L kidney M-L | 0.67 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 1.40 | 0.47 | 0.87 | ||

| R kidney A-P | 0.70 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 1.70 | 0.44 | 0.96 | ||

| L kidney A-P | 0.92 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 1.40 | 0.72 | 1.12 | ||

| R kidney S-I | 1.91 | 0.93 | 2.00 | 0.60 | 3.70 | 1.28 | 2.54 | ||

| L kidney S-I | 1.72 | 0.81 | 1.60 | 0.70 | 3.40 | 1.17 | 2.26 | ||

| Old (9-18 y) | 9 | Age (y) | 12.33 | 3.35 | 12.00 | 9.00 | 18.00 | 9.76 | 14.91 |

| Height (cm) | 151.20 | 14.11 | 149.00 | 132.10 | 175.50 | 140.36 | 162.04 | ||

| Movement (mm): | |||||||||

| Diaphragm | 9.56 | 3.57 | 8.00 | 7.00 | 17.00 | 6.81 | 12.30 | ||

| R kidney M-L | 1.14 | 0.52 | 1.10 | 0.60 | 2.20 | 0.74 | 1.55 | ||

| L kidney M-L | 0.86 | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 2.10 | 0.49 | 1.22 | ||

| R kidney A-P | 1.36 | 0.44 | 1.40 | 0.90 | 2.30 | 1.02 | 1.69 | ||

| L kidney A-P | 0.94 | 0.43 | 0.90 | 0.40 | 1.70 | 0.62 | 1.27 | ||

| R kidney S-I | 3.90 | 1.71 | 3.60 | 1.50 | 6.30 | 2.59 | 5.21 | ||

| L kidney S-I | 3.07 | 1.24 | 3.40 | 0.80 | 4.60 | 2.11 | 4.02 |

Lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence interval are shown.

Abbreviations: A-P, anterior-posterior; CL, confidence limit; L, left; M-L, medial-lateral; Max, maximum; Med, median; Min, minimum; R, right; SD, standard deviation; S-I, superior-inferior

The largest motion vector was observed in the S-I direction in both age groups. Younger patients had a median S-I vector of 2.0 mm (range, 0.6-3.7 mm) for the right kidney and 1.6 mm (range, 0.7-3.4 mm) for the left kidney. The corresponding values for older patients were 3.6 mm (range, 1.5-6.3 mm) for the right kidney and 3.4 mm (range, 0.8-4.6 mm) for the left kidney.

Considering motion in the cardinal x-, y-, z-planes, there was no significant correlation between renal motion and age. In younger patients, there was a borderline significant correlation between young age and the M-L motion of the left kidney (R2 = 0.31).

In the older patients, renal and diaphragmatic motion were correlated; M-L (R2 = 0.47) and S-I (R2 = 0.34) motion of the right kidney correlated with diaphragmatic motion. There was no statistically significant correlation between any of the clinical variables (age, height, weight, BMI) and diaphragmatic motion, except for borderline significance in the correlation between diaphragmatic motion and BMI (r = 0.52, p = 0.0816) in younger patients.

DISCUSSION

Pediatric renal tissue at risk of radiation injury exhibits certain characteristics of physiologic motion that appear to be a function of multivariate phenomena, including physiologic organ motion and deformation. The most salient factors evaluated suggest a relationship between renal motion and age, patient height and diaphragmatic motion, with no strong correlation between organ motion and weight or BMI. Some aspects of this data mirror the adult data, demonstrating the largest vectors of motion in the S-I and M-L directions with small median vectors identified in the A-P dimension. Figure 3 demonstrates a 10 year old girl imaged in the coronal mid-renal plane with high risk Stage 4 retroperitoneal neuroblastoma following induction therapy. The superior motion vector is 4.3 mm through one complete respiratory cycle.

Figure 3.

Coronal mid-plane right kidney imaged at the extremes of the respiratory cycle in a 10 year old girl with stage 4 retroperitoneal high risk neuroblastoma post-induction therapy. (A) Demonstrates 100% inspiration. (B) Demonstrates 25% expiration.

A frequent complication of estimating organ motion is selection of a reference point. The resolution of axial 4DCT limits renal edge detection and measurement; thus, center-of-mass measurements were performed instead. This technique allows assessment of centroid motion but proves difficult to generate strict directional values for motion estimates of the kidneys and associated tumor volumes. Prospective studies with sagittal or coronal MRI would be more appropriate to assess the edges of deformable organs. As age increased, the magnitude of the vectors in the M-L and S-I directions increased correspondingly with a greater relative increase detected in the S-I dimension. Although the age cutoff in this analysis was used to divide the cohort into more homogeneous groups, the linear relationship of increasing organ motion with age suggests that the expected maximum range of absolute organ motion should be attained within a few years of completing pubertal development. Despite the small cohorts, significant relationships between age, and therefore height, were clearly demonstrable.

The utility of respiratory gating appears to be an inverse function of age and abdominal dimensions of the patient. Even the youngest subjects demonstrated a similar phenomenon, with cyclical motion and renal compression displaying a proportional relationship to distance from the diaphragm. However, due to the low absolute magnitude of renal motion, the role of respiratory gating in younger children is limited. Furthermore, no class solutions for estimation of planning organs’ at-risk volume (PRV) and internal target volume (ITV) margins appear likely; this is related to the variability of organ motion among patients independent of age and has not been verified by large-scale interfraction-motion analyses within the same patient. Individualized 4DCT or other organ motion assessment appears unavoidable based on this dataset, particularly as no data exist that confirm the reproducibility of pediatric renal organ motion through serial examinations.

Absolute renal motion vectors appear to be proportionally related to patient age and, by extension, to longitudinal development of each subject's abdomen. Although outliers did exist in both groups of children, the median extent of motion in any direction remained relatively small for the younger cohort. Although the ultimate goal of this analysis is to provide a near-class solution for renal PRVs we conclude based on the size of this sample population that either we had insufficient power to detect a consistent correlation between renal motion and age, height, weight, BMI, use of sedation or diaphragmatic displacement, or there is a fundamental lack of consistency in renal motion in this free-breathing population of pediatric patients aged 2 to 18 years.

Children with neuroblastoma comprise one of the largest pediatric populations at significant risk of locoregional treatment failure within close proximity to the kidneys. Current high-risk neuroblastoma protocols mandate an escalation of radiation dose to 36 Gy in the setting of macroscopic residual disease; thus, the need for a more comprehensive understanding of pediatric intra-abdominal intra- and inter-fraction motion is essential.

Our cohort consisted of children representing a wide spectrum of physical development with various diagnoses including Hodgkin lymphoma, intra-abdominal sarcomas, Wilms tumor, and neuroblastoma. Timing of surgical intervention in this broad cohort varied predominantly by age; when compounded by small sample size, assessment of surgical effect upon renal motion prior to irradiation was not fruitful. Postsurgical adhesions limiting renal motion in young children were evaluated, but imaging failed to confirm their presence. Furthermore, none of these patients had tumor with noted fixation to the peritoneal sidewall; questionable cases were reviewed based on imaging and operative reports. In this cohort, no discernible differences in renal mobility could be ascribed to postoperative or tumor-related organ fixation.

This study represents a crucial step toward designing ICRU-62 compliant guidelines for the pediatric abdomen. To provide data that addresses the void in quantitative data for abdominal organ motion in young children, we have initiated a prospective therapeutic study of IMRT in pediatric patients with high-risk abdominal neuroblastoma. Although maintaining excellent local tumor control is the primary objective, protecting long-term function of abdominal organs is also essential. Thus, estimating the movement of the kidneys, other abdominal organs, and the target volume during IMRT constitutes a key objective of that study.

Axial 4DCT and sagittal/coronal 4DMRI are necessary to examine the center-of-mass motion and renal-edge motion throughout the complete cycle of respiration. These imaging approaches will yield individualized data that are essential for sparing renal function, which is consistent with the recent RT-dose escalation requirements for macroscopic residual neuroblastoma in current national protocols; knowledge of physiologic motion is of even greater importance for intra-abdominal proton therapy guidelines.

As a consequence of MRI; renal scintigraphy; and biochemical, cytokine, and renal neurohormonal assays of pediatric patients who have undergone abdominal IMRT, we will be able to complete a detailed assessment of the functional and morphologic impact of IMRT-induced renal toxicity when coregistered to dosimetric maps. These data will be used to help define radiation-induced changes that occur during the poorly understood latency period in which renal function measures remain normal, but other poorly documented yet detectible changes may occur over a period of several years. These biochemical analyses may provide insight into improved clinical management of radiation-induced renal injury.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results show that pediatric renal motion during the respiratory cycle is governed by age, height, and diaphragmatic motion. Renal motion is asymmetric (i.e., the right kidney tends to move more than the left), and although predictable with 95% confidence intervals, this motion is most likely to require individualized assessment due to variability. Because the use of anesthesia was highly correlated with age, its contribution to smaller motion vectors should not be overlooked. Considering children younger than 9 years, an orientation-specific margin of 5 to 25 mm added to the contoured kidney volume would account for renal motion in all cases. For older children, an orientation-specific margin of 5 to 52 mm would account for renal motion in all cases. These data provide novel preliminary information that will serve as the basis for establishing international guidelines for delivering highly conformal RT within the abdomen of pediatric patients.

Acknowledgments

For editing assistance, we thank Angela McArthur, PhD, ELS. This work was supported in part by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Notification

None of the authors of this manuscript have any actual or potential conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dawson LA, Kavanagh BD, Paulino AC, et al. Radiation-Associated Kidney Injury. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2010;76:S108–S115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolling T, Willich N, Ernst I. Late effects of abdominal irradiation in children: a review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore JE, Jr., Ku DN. Pulsatile velocity measurements in a model of the human abdominal aorta under simulated exercise and postprandial conditions. J Biomech Eng. 1994;116:107–111. doi: 10.1115/1.2895692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taremi M, Ringash J, Dawson LA. Upper abdominal malignancies: intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Front Radiat Ther Oncol. 2007;40:272–288. doi: 10.1159/000106041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murtz P, Pauleit D, Traber F, et al. [Pulse triggering for improved diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the abdomen]. Rofo. 2000;172:587–590. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-4667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumgartner C, Bollerhey M, Henke J, et al. Effects of propofol on ultrasonic indicators of haemodynamic function in rabbits. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2008;35:100–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2007.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faries PL, Agarwal G, Lookstein R, et al. Use of cine magnetic resonance angiography in quantifying aneurysm pulsatility associated with endoleak. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:652–656. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00944-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muhs BE, Teutelink A, Prokop M, et al. Endovascular aneurysm repair alters renal artery movement: a preliminary evaluation using dynamic CTA. J Endovasc Ther. 2006;13:476–480. doi: 10.1583/05-1794MR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad NR, Huq MS, Corn BW. Respiration-induced motion of the kidneys in whole abdominal radiotherapy: implications for treatment planning and late toxicity. Radiother Oncol. 1997;42:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(96)01859-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balter JM, Ten Haken RK, Lawrence TS, et al. Uncertainties in CT-based radiation therapy treatment planning associated with patient breathing. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 1996;36:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mutaf YD, Brinkmann DH. Optimization of internal margin to account for dosimetric effects of respiratory motion. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1561–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rietzel E, Liu AK, Doppke KP, et al. Design of 4D treatment planning target volumes. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2006;66:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz LH, Richaud J, Buffat L, et al. Kidney mobility during respiration. Radiother Oncol. 1994;32:84–86. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(94)90452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Sörnsen de Koste J, Senan S, Kleynen CE, et al. Renal mobility during uncoached quiet respiration: An analysis of 4DCT scans. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2006;64:799–803. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bussels B, Goethals L, Feron M, et al. Respiration-induced movement of the upper abdominal organs: a pitfall for the three-dimensional conformal radiation treatment of pancreatic cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2003;68:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(03)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H, Wu A, Brandner ED, et al. Dosimetric evaluations of the interplay effect in respiratory-gated intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Med Phys. 2009;36:893–903. doi: 10.1118/1.3070542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stroom JC, Heijmen BJM. Limitations of the planning organ at risk volume (PRV) concept. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2006;66:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]