Abstract

Fused in sarcoma (FUS) is involved in many processes of RNA metabolism. FUS and another RNA binding protein, TDP-43, are implicated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). It is significant to characterize the RNA recognition motif (RRM) of FUS as its nucleic acid binding properties are unclear. More importantly, abolishing the RNA binding ability of the RRM domain of TDP43 was reported to suppress the neurotoxicity of TDP-43 in Drosophila. The sequence of FUS-RRM varies significantly from canonical RRMs, but the solution structure of FUS-RRM determined by NMR showed a similar overall folding as other RRMs. We found that FUS-RRM directly bound to RNA and DNA and the binding affinity was in the micromolar range as measured by surface plasmon resonance and NMR titration. The nucleic acid binding pocket in FUS-RRM is significantly distorted since several critical aromatic residues are missing. An exceptionally positively charged loop in FUS-RRM, which is not found in other RRMs, is directly involved in the RNA/DNA binding. Substituting the lysine residues in the unique KK loop impaired the nucleic acid binding and altered FUS subcellular localization. The results provide insights into the nucleic acid binding properties of FUS-RRM and its potential relevance to ALS.

Keywords: Fused in sarcoma, RNA recognition motif, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, nucleic acid binding, NMR, surface plasmon resonance

1. Introduction

Human FUS (fused in sarcoma), also known as TLS (translocated to liposarcoma), is a member of the TET protein family that also include EWS (Ewing’s sarcoma) and TAF15 (TATA-box binding protein associated factor 15) [1]. These proteins are predominantly localized in the nucleus and involved in multiple steps of gene expression and RNA processing including RNA polymerase II transcription [1, 2], pre-mRNA splicing [3, 4], RNA polymerase III transcription repression [5], DNA repair [6] and mature mRNA transportation in neurons [7]. They could also act as oncogenes by incorporating their N-terminal regions into the DNA-binding domains of other transcription activation factors [8]. Attention has been drawn to FUS recently since mutations in FUS have been reported to cause the familial form of the fatal neurodegenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [9, 10]. Interestingly, another RNA binding protein TDP-43 (trans-activating response region DNA-binding protein 43), which has similar primary structural domains as FUS, was also implicated in both familial and sporadic ALS [11, 12]. Both FUS and TDP43 are involved in gene expression regulation and RNA processing, suggesting the potential linkage between the RNA/DNA metabolism and neuronal degeneration [13].

FUS was independently identified as hnRNP P2 protein [14] capable of binding to both RNA and single-stranded (ss)/double-stranded (ds) DNA [15–18]. An in vitro RNA-binding study reported that FUS could bind to RNAs with a common “GGUG” motif [19]. FUS was also found to directly interact with a ss human telomeric DNA, although the recognition mode is unclear [20]. The primary sequence of FUS contains an N-terminal QGSY-rich region followed by a glycine-rich region, an RRM (RNA recognition motif) domain, a C2/C2 zinc finger motif flanked by two RG-rich regions and a C-terminal nuclear localization sequence (NLS) [21–24] (Fig. 1A). The region including the RRM domain, the RG-rich and the zinc finger domains was reported to be largely responsible for binding nucleic acids (both RNA and DNA) [17, 19, 21]. It is debatable whether the RRM domain can bind to nucleic acids and what the recognition mechanism is. One study showed that the RRM domain of FUS has the ability to bind to RNA [19] while the other study reported the opposite results [21]. The nucleic acid binding property is critical to the function of FUS and the related proteins. In fact, abolishing the RNA binding of TDP-43 by mutating critical residues in its RRM domain significantly suppressed its neurotoxicity in Drosophila models of TDP-43 mediated ALS [25, 26]. Thus, it is important to better understand the RNA binding properties of FUS in more detail, particularly the RRM domain. To achieve this goal, we therefore set to determine the atomic structure of the RRM domain of FUS.

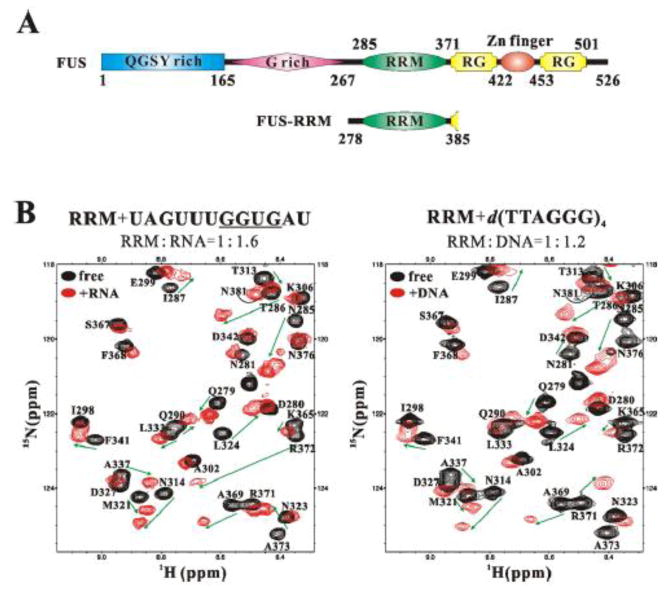

Figure 1. The FUS-RRM domain binds to both RNA and DNA.

(A) Domain organization of the FUS protein and the domain boundaries of the constructs used in this study. FUS contains a QGSY-rich region and a glycine-rich region, a central RRM domain, a C2/C2 zinc finger motif flanked by two RG-rich regions and a C-terminal nuclear localization sequence. (B) An overlay plot of 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the FUS-RRM domain (black, both panels) and that of the domain titrated with RNA UAGUUUGGUGAU (red, left panel) and 24-mer DNA d(TTAGGG)4 (red, right panel), showing significant peak shifts.

The RRM domain is a common RNA-binding domain in eukaryotes, carrying the RNP-featured consensus sequences RNP1 and RNP2 [27]. Most hnRNP proteins contain one or more RRM domains that mediate the direct interaction between the nucleic acid and the proteins to control both RNA processing and gene expression [28]. A canonical RRM domain has a β1-α1-β2-β3-α2-β4 fold with a four-stranded β-sheet and two perpendicular α-helices (Supplementary Fig. S1A). The consensus sequence of RNP1 and RNP2 locate in the two middle strands β3 and β1, respectively. The complex structures of the RRM domains from hnRNP A1 (PDB ID: 1UP1), hnRNP D (PDB ID: 1WTB) and TDP-43 (PDB ID: 3D2W) in complex with DNA revealed that the nucleic acid binding pocket of the domain is largely formed by the central four-stranded sheet and enriched with highly conserved aromatic and positively charged residues (Supplementary Fig. S1). More importantly, the structural-based sequence alignment shows that these essential aromatic residues are largely absent in FUS-RRM (Supplementary Fig. S1B). In particular, the F147 and F149 residues in TDP-43 that were shown to be critical to RNA binding and TDP-43 toxicity [25] are E336 and T338 in FUS, respectively. Such dramatic difference prompted us to characterize the structure and RNA binding properties of FUS-RRM.

Hereby, we report that the FUS-RRM domain can directly bind to both RNA and DNA in vitro. The solution structure of the FUS-RRM domain was determined by NMR spectroscopy. The domain adopts the classical β1-α1-β2-β3-α2-β4 fold but it contains an extra long loop between α1 and β2. This expanded α1/β2 loop (denoted as the “KK” loop) contains several evolutionarily conserved lysine residues and is critical to the nucleic acid binding. Interestingly, the “KK” loop is absent in the two RRM domains of TDP-43 and other RRMs. Our results show that the conventional nucleic acid binding surface formed by the central β1 and β3 sheets is distorted and the canonical ring stacking interaction is largely absent in FUS-RRM interaction with nucleic acids. Instead, the “KK” loop together with other charged residues constitute a positively charged surface area. NMR titration experiments determined that the nucleic acid binding site of the FUS-RRM domain exactly resides at the positively charged surface area. Binding affinity between FUS-RRM and various forms of nucleic acid was measured by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and NMR titration. Mutating the positively charged residues in the “KK” loop caused significantly reduced nucleic acid binding ability of FUS-RRM and altered FUS subcellular localization. Hence, this work unequivocally provides mechanistic insights into the nucleic acid binding features of the FUS-RRM domain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein expression and purification

The DNA fragment encoding the FUS-RRM domain (residues 278–385) was cloned into the pET-22b bacterial expression vector between NdeI and XhoI sites. Point mutations of the FUS-RRM domain (K312A, K315A/K316A, K312A/K315A/K316A) were created using the standard PCR-based mutagenesis method and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Recombinant proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta host cells at 37 °C. The His6-tagged fusion proteins were purified by Ni2+-IDA agarose affinity chromatography. The native FUS-RRM was further purified by two-step purification using the Heparin column (GE Healthcare) and the Superdex75 column (GE Healthcare). Uniformly isotope-labeled FUS-RRM was prepared by growing bacteria in M9 minimal medium using 15NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen source or 15NH4Cl and 13C6-glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc.) as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources, respectively. The NMR samples were concentrated to ~0.1–0.15 mM (for titration experiments) or ~1 mM (for structural determination) in 20 mM Tris-HC1, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.0, 0.02% NaN3 and 0.5 mM DSS. Mutant proteins and NMR samples were prepared using the same protocol described above.

2.2. NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were acquired at 25°C on a Bruker DXR 600 spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe. The sequential backbone resonance assignments were achieved by using standard triple-resonance experiments: HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HNCA [29, 30]. Non-exchangeable side chain resonance assignments were achieved with the help of the following spectra: HBHA(CO)NH, CCH-TOCSY, HCCH-TOCSY, HCCH-COSY [30, 31]. Approximate inter-proton distance restraints were derived from three 3D NOESY spectra (all with 100ms mixing time): 13C-edited NOESY, 15N-edited NOESY and 13C-edited NOESY for the aromatic region. The spectra were processed with the program of NMRPipe [32] and analyzed with Sparky [http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/home/sparky/].

2.3. Structure determination and analysis

Structures were calculated using the program CNS [33, 34]. Hydrogen bonding restraints were generated from the standard secondary structure of the protein based on the NOE patterns and backbone secondary chemical shifts. Backbone dihedral angle restraints (φ and ψ angles) were derived from the secondary structure of the protein and the backbone chemical shift analysis program TALOS[35]. A total of 400 structures were calculated and the final 20 structures with the lowest total energy and least experimental violations were selected to represent the FUS-RRM structure. The atomic coordinate of the FUS-RRM domain has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 2LCW. The protein structure ensemble was displayed and analyzed with the software of MolMol [36] and PyMol (http://www.pymol.org/).

2.4. DNA/RNA, NMR titrations and the dissociation constants

The GGUG-containing RNA UAGUUUGGUGAU (Invitrogen), ss telomeric DNAs d(TTAGGG)4 (24-mer) and d(TTAGGG) (6-mer), and a ds telomeric DNA d(TTAGGG/CCCTAA)4 (ds-DNA) were chemically synthesized and purified with HPLC by Sangon. The solid DNA/RNA samples were dissolved in the NMR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.0) to make stock solutions of concentrations of 3.5–4.5 mM before titrating into the protein samples. The concentrations of the nucleic acid solutions were calculated from the optical absorbance values. For the ds-DNA d(TTAGGG/CCCTAA)4 and the ss 24-mer d(TTAGGG)4, the samples were heated to 95°C for five minutes and cooled gradually in room temperature overnight to form the duplex and quadruplex conformations.

The possible binding interface residues were determined from the Chemical Shift Perturbation (CSP) data calculated by the formula (1),

| (1) |

where ΔH and ΔN are the chemical shift differences between the free and bound form of the proton and nitrogen atoms respectively. The standard deviation of the CSP was calculated according to the formula (2),

| (2) |

where CSPres is the residue-specific CSP, CSPavg is the averaged CSP of all residues and Nres is the number of residues (except those unassigned and proline residues). The residues with CPSs above the averaged CSP were considered to be possible binding interface residues. Residues with CSPs above averaged CSP plus one standard deviation were considered having direct contact with the nucleic acid.

The interaction dissociation constant (Kd) for the fast exchange binding process was estimated for separated residues in those contacting regions described below (in the ‘The nucleic acid binding interface of the FUS-RRM domain’ of the Results section) by curve fitting the one-site-bind model as in formula (3),

| (3) |

where x is the concentration of the DNA/RNA in solution, Bmax is the maximum CSP when ligand concentration is ∞, K is the dissociation constant and y is the CSP.

2.5. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) analysis

The nucleic acid samples used in the SPR analysis had the same sequence as those used in the NMR titration experiments above, but were labeled with a biotin and a AAAAA linker at the 5′-end. All SPR experiments were carried out at 25°C using a BIAcore T100 instrument (GE Healthcare). Streptavidin was immobilized to a CM5 sensor chip by the amine-coupling method. The biotin-labeled DNA/RNA was captured by streptatividin at different channels for 41–104 resonance units (Ru). The binding experiments were carried out in the running buffer (20 mM Tirs, pH 7.5, 50mM NaCl and 0.005% [v/v] Tween 20) at the flow rate of 30 ul/min. Wild type RRM and each mutant prepared at various concentrations in the running buffer were injected over the sensor surface for 60 s and dissociated for 60 s. Curve fitting was done with Biacore T100 evaluation software (GE Healthcare). Since the release at the end of the injection is almost instantaneous, the KD was estimated by the steady state affinity model.

2.6. Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

The CD spectra of the nucleic acids were collected on a JASCO J-720 CD spectrometer in room temperature. For each sample (300ul in a 0.1 cm light-path cell), three scans were accumulated in the wavelength range of 220–340 nm at a scanning rate of 30 nm/min with a 0.5 nm step size. CD data were collected in the unit of millidegrees versus wavelength. All nucleic acid samples and protein samples were dissolved in the NMR buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, 50mM NaCl, pH7.0) and the concentrations were 100 μg/ml for the nucleic acids (except 60 μg/ml for the ss 6-mer) and 0.5 mM for the protein. The raw CD data were subtracted by the buffer or the protein (for the protein/nucleic acids titration measurements). The CD data was also subtracted by the zero-position values that were determined by averaging the 10 data points at wavelength 335–340 nm. These data were then smoothed three times using the 3-point-smoothing method.

2.7. Confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy was used to determine whether the mutations in the “KK” loop of FUS-RRM affected the subcellular localization of FUS. Neuroblastoma 2a (N2a) cells were seeded into 12-well plate with gelatin-coated 18-mm converslips inside. Various GFP-FUS constructs were generated and transfected into N2a cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as previously published [37]. 24 hours after transfection, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized by 0.1% Triton X-100. The nuclei were stained by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The coverslips were mounted and images were acquired using an Olympus confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview, Ver.1.7c).

3. Results

3.1. The FUS-RRM domain binds to both RNA and DNA

RNA binding proteins including FUS and TDP-43 are an emerging group of proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases. Given the significant variations of FUS-RRM from canonical RNP1/RNP2 sequences (Supplementary Fig. S1B) and the controversial nucleic acid-binding capacities, we first purified the FUS-RRM domain (residues 278–385, Fig. 1A) and characterized its nucleic acid binding properties by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and NMR titration. NMR titration experiments of FUS-RRM with four different forms of nucleic acid (RNA, ss 6-mer DNA, ss 24-mer DNA with G-quadroplex secondary structure, and ds DNA) were performed. Significant chemical shift changes were observed upon the addition of nucleic acids, clearly demonstrating the direct interaction between the FUS-RRM domain and both RNA and DNA (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, an independent SPR approach was employed to measure the interaction between FUS and nucleic acids. The binding affinities (dissociation constants) were calculated from both NMR titration and SPR approaches and are shown in Table 1. The results from both experiments support that FUS-RRM indeed bound to various forms of nucleic acids.

Table 1.

Dissociation constants of FUS-RRM binding with various forms of nucleic acids

| RNA | 6-mer | 24-mer | ds-DNA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR determination | 132 μM | 310 μM | 23 μM | 227 μM |

| NMR estimation | 146–260 uM | 171–209 μM | N/A * | 26–43 μM |

Not measured because this is an intermediate exchange process.

3.2. The solution structure of FUS-RRM

To gain more insights into the binding properties of the FUS-RRM domain, we next determined the 3D atomic structure. Preliminary crystalization screening of the FUS-RRM domain did not yield useful crytals, possibly due to several large flexible regions in the domain (Fig. 2). NMR spectroscopy was consequently employed to determine the solution structure of FUS-RRM. The excellent 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the FUS-RRM domain demonstrated the high likelihood of solving the solution structure (Supplementary Fig. S2).

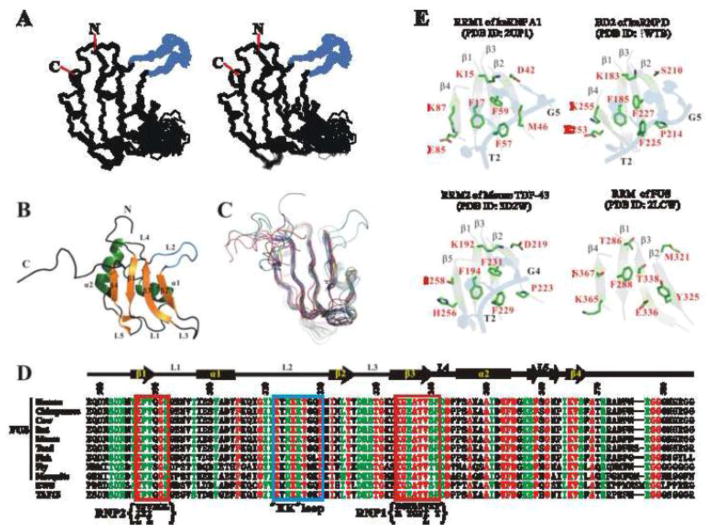

Figure 2. The solution structure of the FUS-RRM domain (PDB ID: 2LCW).

(A) Stereo-view showing the backbones of 20 superimposed NMR-derived structures of the FUS-RRM domain. The flexible N- and C-termini of the protein are removed for clarity. The extra long L2 loop is shown in blue. (B) Ribbon diagram of a representative NMR structure of FUS-RRM. The secondary structures of FUS-RRM are labeled similarly as in the canonical RRM domain. (C) Superimposed plot of the FUS-RRM domain with other RRM domain structures randomly selected from the Protein Data Bank (PDB IDs: 1H2V, 1HD0, 1L3K, 1SJQ, 1UP1, 1WF2, 1X4B, 2DH9, 2DO0, 2HGL, 2X1A, 3BS9, 3HI9 and 2DGV). The FUS-RRM domain contains a long extended L2 loop whereas most of the other RRM domains contain a single residue in the place of this loop. (D) Sequence alignment of the FUS-RRM domain from different species and RRM domains from human EWS and TAF15. The identical residues are colored in red, highly conserved residues are in green and other residues are in black. The residue numbers and the secondary structures of human FUS-RRM are marked on the top. The RNP1 and RNP2 regions are enclosed in the red boxes with the consensus sequence shown at the bottom. The extra long L2 loop (the “KK” loop) is enclosed in a blue box. (E) Ribbon and stick diagrams showing the solvent exposed residues in the central β-sheets of the RRM1 of the hnRNP A1 interacting with DNA (2UP1) and the corresponding residues in BD2 of the hnRNP D (1WTB), RRM1 of mouse TDP-43 (3D2W) and the RRM domain of FUS. The central β-sheets were drawn in grey with 50% transparent to emphasize the surface exposing residues. The side chains of the exposed residues are drawn in explicit atomic model and labeled in red. The DNA fragments are drawn in 50% transparent blue cartoon diagram to show the ring stacking interactions with the aromatic residues in the RRM domains. 3′ and 5′ end of the DNA fragment are labeled in black.

The solution structure of the FUS-RRM domain determined by NMR spectroscopy is shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1 (PDB ID: 2LCW). Except for the N- and C- termini and two loops (residues 312–320 and 327–332) the overall protein structure was well defined (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table S1). The overall protein topology adopts a canonical β1-α1-β2-β3-α2-β4 fold with the defined secondary structures connected by five loops (L1 to L5) (Fig. 2B and 2C). The central β-sheet consists of β1-β4 and rests against a scaffold comprised of two α-helices (α1 and α2). Sequence alignment of the FUS-RRM domains from different species reveals that the residues for the central hydrophobic core packing are highly conserved (Fig. 2D). Compared to other RRM domains, a significant difference is an extra long L2 between α1 and β2 (residues K312 to P320, Fig. 2C). This loop is conserved in FUS sequences from all organisms and within the TET family (Fig. 2D) but absent in other RRMs and the other ALS related protein TDP-43 (Supplementary Fig. S1B). This loop is named as the “KK” loop because of the highly conserved lysine residues. Interestingly, the “KK” loop protrudes from the central structure core and resembles an extended arm from the domain and thus distinctive to other RRM domains (Fig. 2A, 2B and 2C).

We next compared the FUS-RRM with three classic RRMs, the hnRNP D BD2 (1WTB), the hnRNP A1 RRM1 (2UP1), and the RRM2 of mouse TDP-43 (3D2W) (Fig. 2E). Each of the hnRNP RRM domains can accommodate three or four nucleotides of the telomeric sequence d(T1T2A3G4G5G6), the d(T2A3G4) or d(T2A3G4G5) [38, 39]. The TDP-43 RRM2 specifically recognizes the d(T2T3G4) of the 10 mer DNA d(G1T2T3G4A5G6C7G8T9T10) [40]. As observed in most other RRM-nucleic acid interactions, the highly conserved aromatic residues from both the RNP1 and the RNP2 and positively charged residues from the β1 and the β4 in hnRNP A1 RRM1 directly interact with DNA through ring stacking and electrostatic interaction/hydrogen bonding. For instance, most of the solvent exposed residues from the central sheet of hnRNP A1 RRM1 (K15, F17, D42, M46, F57, F59, E85, K87) were directly involved in the interaction with the telomeric DNA [39]. Similarly, the corresponding surface residues in the hnRNP D BD2 are mostly identical (K183, F185, F225, F227, E253 and K255) except for the residues in β2 (D42→S210, M46→P214) that leads to the loss of recognizing the second guanine (G5) [38] (Fig. 2E). It is also evident in Fig. 2E that the nucleic acid binding site of RRM2 of TDP-43 is nearly identical to that of RRM1 of hnRNP A1. In contrast, the corresponding residues in the corresponding binding surface of the FUS-RRM domain are quite different. Two conserved Phe residues in the RNP1 (F57 and F59 in hnRNP A1 RRM1, F225 and F227 in hnRNP D BD2, F147 and F149 in TDP-43 RRM1 and F229 and F231 in TDP-43 RRM2) are replaced by E336 and T338 in FUS-RRM. The positively charged Lys residues in the β1 and the β4 are substituted by T286 and S367 in FUS-RRM (Fig. 2E). Moreover, these non-canonical residues E336, T338, T286 and S367 are highly conserved in FUS from different organisms (Fig. 2D). Therefore, the classical nucleic acid binding surface of the FUS-RRM domain is largely disrupted and the binding feature of FUS-RRM is likely to be different from other canonical RRMs.

3.3. The nucleic acid binding interface of the FUS-RRM domain

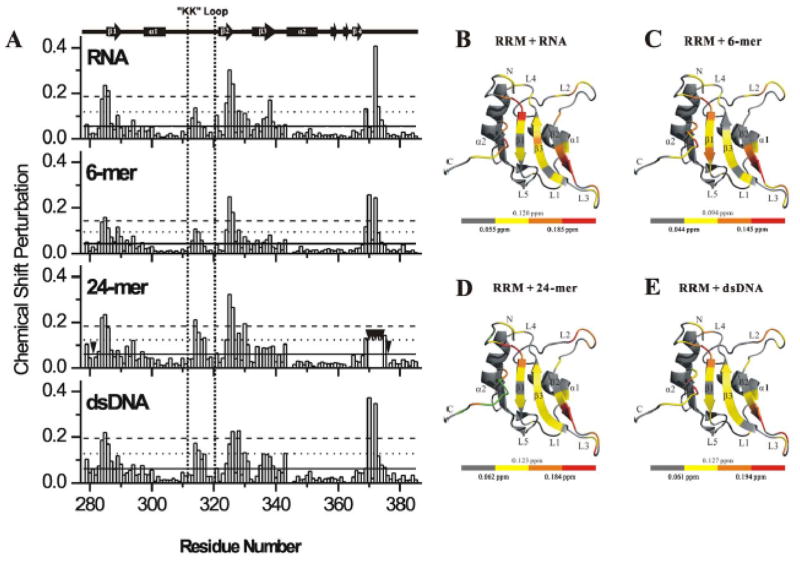

To determine the nucleic acid binding features of FUS-RRM, we performed extensive NMR titration experiments to map the exact nucleic acid binding surface. With addition of the RNA (UAGUUUGGUGAU), a sub-set of peaks undergoes significant chemical shift changes (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Interestingly, a similar sub-set of peak changes were observed upon addition of various DNA molecules (Supplementary Fig. S3B–D). Chemical shift perturbation data analysis showed that roughly five clusters (residues N284-I287, T313-T317, L324-G331, E336-V339 and A369-N376) are involved in the interaction interface between the FUS-RRM domain and the nucleic acids (Fig. 3A). It is noted that E336-V339, which is within in the canonical RNP1 site showed relatively smaller chemical shift changes as compared to the other four clusters. The above residues with significant chemical shift changes are mapped to the 3D structure of the FUS-RRM domain. Surprisingly, the nucleic acid binding surface still resides in the central sheet (Fig. 3B-E) although the critical aromatic residues in the region of RNP1 (residues K334-F341) are missing. This is evident when the DNA and RNA binding residues in FUS-RRM and the BD2 domain of hnRNP D are highlighted side by side in Supplementary Fig. S4. This suggests that the nucleic acid binding to FUS-RRM is likely to adopt similar configuration as in other RRMs but the binding might be weaker or additional structural components would also contribute to the binding due to the substitution of the critical aromatic residues in RNP1. Interestingly, the “KK” loop (L2) endures significant changes upon being titrated with all nucleic acids, especially ds DNA and 24-mer DNA (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S3). This suggests that this positively charged “KK” loop, which is expanded and unique in FUS-RRM (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. S1B), is a key site for the nucleic acid binding. Taken together, although the classical RNP1 site of FUS-RRM lacks the critical hydrophobic residues and is largely disrupted, the unique expanded “KK” loop makes additional contribution to enhance the nucleic acid binding.

Figure 3. Mapping the nucleic acid binding interface of the FUS-RRM domain.

(A) The histogram shows chemical shift perturbation profile of each residue of FUS-RRM upon binding to GGUG containing RNA UAGUUUGGUGAU, 6-mer d(TTAGGG), 24-mer d(TTAGGG)4 and ds-DNA d(TTAGGG/CCCTAA)4. The residues disappeared in titration of 24-mer due to exchange broadening are indicated by inverted black triangles. In each panel, the solid, dotted and dashed horizontal lines correspond to the averaged CSP, one and two standard deviations above the averaged CSP respectively (see the Experimental Procedure section for details). (B–E) Mapping of the chemical shift perturbation (CSP) induced by RNA (B), 6-mer DNA (C), 24-mer DNA (D) and ds-DNA (E) onto the ribbon diagram of the FUS-RRM domain. The scale of the color scheme is shown at the bottom of each panel. The scales indicate averaged CSP, averaged CSP plus one standard deviation and averaged CSP plus two standard deviations, respectively, from left to right. Green colored regions in (D) represent disappeared residues on addition of the 24-mer DNA.

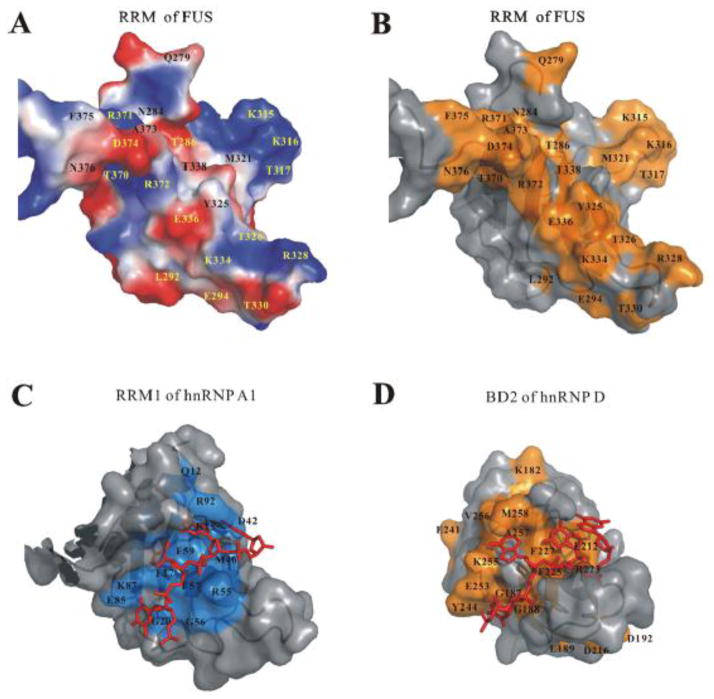

Based on the above structural analysis, we propose that the interactions between FUS-RRM and nucleic acids are largely mediated by charge-charge attractions. The solvent exposed residues on the four-strand β sheet of FUS-RRM are largely polar residues and accompanied with the positively charged surface areas. Figure 4A shows the charged residues on protein surface of FUS-RRM. It is noted that the highly positively charged “KK” loop contributes significantly to the positively charged surface area. Figure 4B shows the residues with significant chemical shift changes on the protein surface of FUS-RRM. Compared to the protein surface residues involved in nucleic acid binding in RRM1 of hnRNP A1 (Fig. 4C) and BD2 of hnRNP D (Fig. 4D), an expanded positively charged surface area is clearly involved in the nucleic acid binding.

Figure 4. FUS-RRM contains an expanded positively charged surface for nucleic acid binding.

(A) Electrostatic surface representation of FUS-RRM shows a prominent positively charged surface area for nucleic acid binding. The positively charged potential is in blue and the negatively charged potential is in red. (B) Protein surface of FUS-RRM with the residues with significant chemical shift changes upon DNA binding colored in orange. The nucleic acid binding pocket aligns with the the positively charged protein surface areas. (C–D) Surface combined with ribbon diagram representations of the hnRNP A1 RRM1/DNA complex (C) and hnRNP D BD2/DNA complex (D). The DNA fragments are drawn in stick representation in red. The protein surface residues involved in DNA binding in hnRNP D are derived from the CSP [58] and also colored in orange while the residues involved in binding in hnRNP A are derived from its X-ray structure [39] and colored in marine. The surface area involved in nucleic acid binding is larger in FUS-RRM (B) compared to (C) and (D).

This binding model is significantly different from the canonical RRM-nucleic acid interaction in which ring stacking between the aromatic residues in RRM and bases in nucleic acids is critical. This is consistent with the earlier sequence analysis that two critical Phe residues in RNP1 of FUS-RRM are missing.

As a control, circular dichroism (CD) was employed to monitor the conformation of the nucleic acids in the absence and presence of FUS-RRM. The ss 6-mer, ds-DNA and ss 24-mer showed distinct CD features consistent with the single-stranded, double-stranded and G-quadruplex structures, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S5A). The ss G-quadruplex 24-mer DNA had a negative band at 263 nm and a positive band at 295 nm while the ds-DNA showed a negative band at 240 nm and a positive band at 266 nm [41, 42]. Upon addition of various concentrations of FUS-RRM, no conformational changes of the nucleic acids were observed. Supplementary Fig. S5B and S5C show the CD spectra of G-quadruplex 24-mer and ds-DNA, respectively.

3.4. The binding affinity between FUS-RRM and nucleic acids

The binding affinity of between FUS-RRM and nucleic acids was determined by SPR as well as estimated by NMR titration. The NMR titration curves are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6 and the SPR response curves are shown in Supplementary Fig. S7. The binding affinities measured from both approaches are compiled in Table 1. The relatively low binding affinity with RNA (Kd ~ 132–260 μM) suggests that FUS-RRM may not bind specific RNA sequences, both of which could be favorable for its function involved in RNA trafficking and pre-mRNA splicing (see details in Discussion).

The chemical shift changes in the NMR titration experiments showed consistent DNA binding surface within FUS-RRM (Fig. 3 and S3). The affinities of different DNA molecules binding to the FUS-RRM varied in the range of ~20–200 μM. The shorter ss telomeric DNA 6-mer had a relatively low affinity similar to that of RNA and the Kd values obtained from both methods were consistent (Table 1). The ds-DNA showed a higher binding affinity (Kd ~ 26–43 μM) in the NMR experiment but a lower affinity (Kd ~ 227 μM) in the SPR analysis. The discrepancy might indicate that multiple binding happened in the process, e.g. several protein molecules bound to one ds-DNA. The 24-mer DNA showed the strongest binding and a medium to slow exchange NMR spectrum (Fig. 3A), thus no Kd was obtained. SPR measured the Kd to be 23 μM, which was consistent with the range of low micromolar suggested by NMR.

As discussed earlier, the multiple positively charged residues on the nucleic acid binding surface and the “KK” loop suggest that the nature of the interaction is electrostatic interaction. Such interaction is consistent with the low-affinity and low-specificity binding with multiple forms of nucleic acids observed here. To further support this conclusion, we determined the salt dependence of the interaction by performing SPR analysis using buffers containing different salt concentrations. The Kd values shown in Table 2 demonstrate a strong salt dependence of the interaction. For instance, the Kd of the 24-mer was 23 μM in the presence of 50 mM NaCl, 214 μM in 100 mM NaCl and 2.5 mM in 200 mM NaCl. The results further support the electrostatic nature of the interaction.

Table 2.

Salt dependence of the dissociation constants determined by SPR

| Salt Concentration | 50 mM | 100 mM | 200 mM |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA | 132 uM | 422 uM | 4.5 mM* |

| 24-mer | 22.9 uM | 214 uM | 2.5 mM* |

| ds-DNA | 227 uM | 2.6 mM* | ND |

The mM dissociation constants in the higher salt concentrations (100 mM and 200 mM) were only estimations because the saturation conditions could not be reached in the analysis.

3.5. The unique “KK” loop is essential for nucleic acid binding

The results so far support an intriguing model of FUS-RRM binding with nucleic acids in which ring stacking makes less contribution than electrostatic interactions from the protein surface residues. This model also suggests that the interaction is characteristic of low affinity and low specificity, explaining that FUS can bind to various forms of nucleic acids, from RNA to DNA, from single-stranded to duplex and G-quadruplex. In particular, the unique “KK” loop in FUS-RRM, which is absent in other RRM domains, helps to construct the positively charged surface and makes critical contribution to the electrostatic interaction with the negatively charged phospho-backbones of nucleic acids. To test this hypothesis, we made point mutations of the positively charged residues of the “KK” loop: K312A, K315A/K316A and K312A/K315A/K316A. SPR experiments showed that the mutation of these lysine residues greatly reduced or abolished the binding, e.g. the Kd of K312A to 24-mer decreased to 103 μM as compared to 22.9 μM of wild-type RRM. The binding of the K315A/K316A and K312A/K315A/K316A to nucleic acids decreased so much that the dissociation constants became un-measurable.

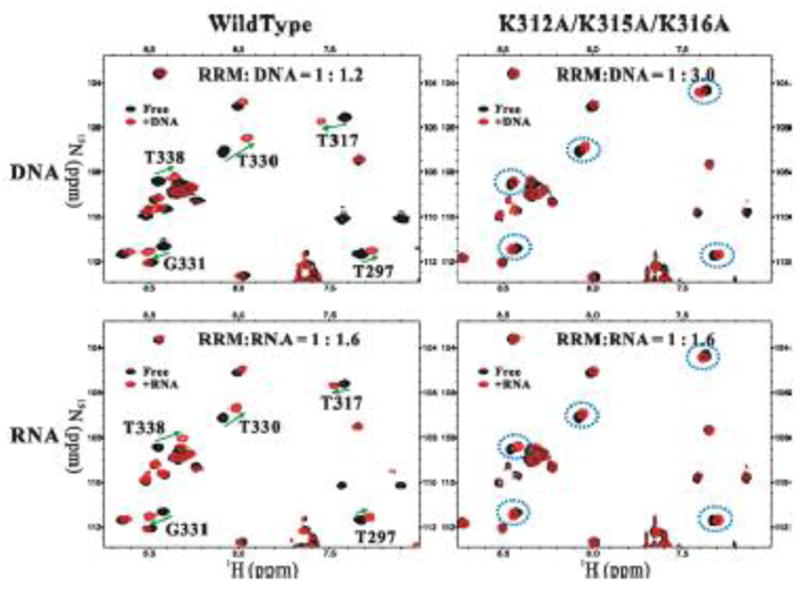

The 1H-15N HSQC spectra of K312A/K315A/K316A mutant in the presence and absence of nucleic acids were compared to those of wild-type FUS-RRM (Fig. 5). The mutation caused limited chemical shift changes in the close neighbors of the mutation sites (Supplementary Fig. S8), indicating that the global folding of FUS-RRM was minimally impacted by the point mutations. The chemical shift changes observed in wild-type FUS-RRM upon titration of 24-mer DNA and RNA are marked with arrows in Fig. 5 (left column). The K312A/K315A/K316A mutant showed very small chemical shift changes upon titration of 24-mer DNA or RNA (Fig. 5 right column). The results support our model that the “KK” loop region plays a critical role in nucleic acid binding.

Figure 5. The “KK” loop is essential for FUS-RRM interaction with nucleic acid.

An overlay plot of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the FUS-RRM domain (black) and that of the domain titrated with nucleic acids (red). The overlaid spectra show the chemical shift changes of the wild-type FUS-RRM (left column) and the K312A/K315A/K316A mutant (right column) when titrated with the 24-mer DNA (upper row) and RNA (lower row). The peaks with significant changes are marked and the changes are highlighted by green arrows in the spectrum of the wild-type FUS-RRM and the corresponding peaks in the mutant spectra are circled with blue dotted line. The ratio of protein to nucleic acid is labeled on the top of each spectrum.

3.6. The subcellular localization of FUS-RRM mutants

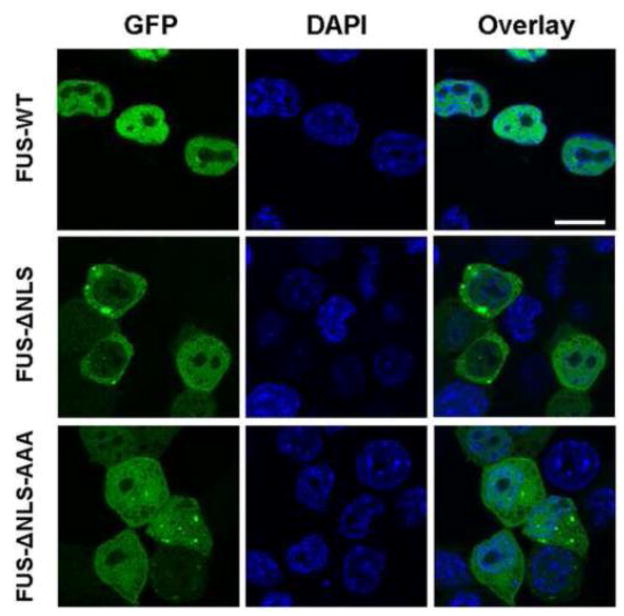

We next tested whether the “KK” loop mutations would change the subcellular localization of FUS. We and others have previously published the C-terminal nuclear localization sequence (NLS) in FUS [37, 43, 44]. The NLS is highly effective and mutations outside the NLS in the context of the full-length FUS always showed a primary localization in the nucleus (data not shown), thus we tested the “KK” loop mutant K312A/K315A/K316A in the context of FUS-ΔNLS. As shown in Figure 6, wild-type full-length FUS was primarily localized in the nucleus whereas FUS-ΔNLS accumulated in the cytoplasm, which is consistent with previous publications. The “KK” loop mutant (FUS-ΔNLS-AAA) reversed the cytoplasmic accumulation and showed even distribution in both nucleus and cytoplasm. The result suggests that the “KK” loop mutation without RNA binding capability can either suppress nuclear export or facilitate nuclear accumulation or both.

Figure 6. The effect of “KK” loop mutation on FUS subcellular localization.

The GFP-tagged wild-type full-length FUS (top), truncated FUS without the C-terminal NLS (FUS-ΔNLS, middle) and the “KK” loop mutant (FUS-ΔNLS-AAA, bottom) were transfected into N2a cells. Representative confocal microscopic images of GFP-FUS and DAPI-stained nucleus are shown. The “KK” loop mutation reversed the cytoplasmic accumulation of FUS-ΔNLS and showed even distribution in both nucleus and cytoplasm. The scale bar is 10 μm.

4. Discussion

This study reconciles the controversy of nucleic acid binding ability of the RRM domain of FUS and clearly demonstrates that FUS-RRM can bind both DNA and RNA using both SPR and NMR techniques (Table 1; Fig. 1, 3, S3, S6 and S7). Our structural characterization has also shown two prominent features of FUS-RRM that are different from the canonical RRM domains: (i) an expanded protein surface area for nucleic acid binding and (ii) a unique, extra-long, positively charged “KK” loop that is essential for nucleic acid binding. This study reveals an intriguing mechanism by which FUS-RRM binds to nucleic acids.

The canonical RRM domains employ conserved aromatic residues in the RNP1 and RNP2 motifs to bind ssDNA or RNA primarily through ring-stacking interactions between the aromatic residues and bases. However, many such aromatic residues are substituted by polar residues in FUS-RRM (Fig. 2D), thus ring-stacking is not the primary interaction mechanism for the FUS-RRM interaction with nucleic acids. This also explains that FUS-RRM binds to ssDNA and RNA with low sequence specificity and low affinity (Table 1). Instead, an extended “KK” loop between α1 and β2 is unique in FUS (Fig. 2C). The positively charged “KK” loop plays a critical role in nucleic acid binding (Fig. 5) and contributes to the regulation of FUS subcellular localization (Fig. 6). NMR titration experiments also identified several auxiliary components that are involved in nucleic acid binding, including the N-terminal region (Q279, N284, N285, T286), the loop L3 connecting β2 and β3 (L324, Y325, T326, D328, E330, T331) and the C-terminal flexible part (the region between T369 and N376) (Fig. 3). These residues together form an expanded protein surface where nucleic acids bind to FUS-RRM likely through electrostatic interaction (Fig. 4).

Tremendous interest has been focused on understanding the role of FUS in ALS in recent years. It is particularly interesting that FUS and TDP-43 are both RNA binding proteins and that both are implicated in sporadic and familial ALS [11, 12]. It is particularly important to characterize the RNA binding properties of the RRM domain because elimination of the RNA binding of TDP-43 by mutating critical residues in the RRM domain significantly suppressed its neurotoxicity in Drosophila models of TDP-43 mediated ALS [25, 26]. Comparison of the structure of FUS-RRM determined in this study to the RRM2 domain in TDP-43 [40] reveals significant differences. TDP-43 has two RRM domains and both resemble the canonical RRMs. The phenyalanine residues critical to ring stacking interaction are conserved in TDP-43 RRM domains. There is no positively charged “KK” loop in TDP-43 RRM domains. These significant differences between the RRM domains of FUS and TDP-43 revealed in this study suggest that the pathological etiology of FUS- and TDP43-mediated ALS may not be exactly identical. The results from this study also help provide significant insights to guide future studies. For instance, the lysine mutations in the “KK” loop can be used to examine the significance of RNA binding in FUS neurotoxicity. These studies are currently under investigation in our laboratories using the Drosophila models that we recently published [45].

Our SPR and NMR analysis consistently found the binding affinity between FUS-RRM and RNA to be in the range of 132 to 260 μM (Table 1). In contrast, both RRM domains of TDP-43 preferred to bind to RNA with more UG repeats with a Kd in the range of nM and low μM [40]. Several hundred RNAs have been reported to bind to TDP-43 [46]. Moreover, the ALS-related TDP-43 mutations could cause splicing alterations in several hundred message RNAs [46, 47]. Most recently, thousands of RNAs were reported as FUS binding targets in HEK293 cell line [48] as well as in mouse and human brain [49]. It is still unknown how many splicing events are mediated by FUS or what splicing changes are caused by the ALS-related mutations in FUS. Based on the low binding affinity measured in this study and the anticipated low sequence specificity of the FUS-RRM interaction with RNA, it is not surprising that FUS could bind to a large number of RNAs. In support of FUS/DNA binding observed in this study, a recent study demonstrated that FUS can bind to the promoter elements of many genes [50]. It remains to be determined whether the RRM motif is the major site of nucleic acid binding in live cells. There is a zinc-finger domain located C-terminal of the RRM motif and it is possible that the zinc-finger domain may bind nucleic acids with higher affinity and specificity. In addition, the RRM motif may also be involved in protein-protein interaction since its interaction with nucleic acids is rather weak. The two possibilities will be addressed in future studies.

A recent study screened 213 human RRM-containing proteins and found a cohort of RNA-binding proteins that can cause protein aggregation and toxicity when overexpressed in yeast [51]. The study identified another TET family member TAF-15 as a potential ALS gene since point mutations in TAF-15 were found in several ALS patients but not in healthy controls. The study further suggested that the third member of the TET family EWS may also harbor mutations in ALS patients [51]. Other studies showed that TAF-15 and EWS may be involved in ALS as well [52, 53]. Our structural analysis and sequence alignment suggest that the RRM domains of FUS, TAF-15 and EWS share the same features: lack of hydrophobic residues for conventional ring-stacking interaction and existence of an expanded “KK” loop (Fig. 2D). These features are distinct from the canonical RRM domains including the two RRM domains in TDP-43. In order to determine the role of these proteins’ RNA binding properties in ALS disease, it is critical to characterize the RRM domain structure and to understand the RNA binding mechanism first. From this perspective, the findings of this study provide significant insights into these proteins with similar features in their RRM domains.

Since the cytoplasmic accumulation of FUS, TAF-15 and TDP43 is a hallmark of the disease, it is conceivable that the RRM domain could contribute to the pathology of the ALS by influencing the subcellular localization of these RNA-binding proteins. An additional possibility is that the RNA binding property may directly contribute to the physiological function of FUS, TAF-15 and TDP-43 as well as their dysfunction in disease pathology. Interestingly, the “KK” loop in FUS-RRM is critical to both RNA binding (Fig. 5) and subcellular localization (Fig. 6) in our studies. It is noted that the ALS related mutations identified so far are clustered in the C-terminal nuclear localization sequence (NLS) of FUS. Nuclear targeting by NLS and RNA binding by RRM are the two distinct but related properties of FUS. It is conceivable that the RNA binding could potentially influence the subcellular localization (as evidenced in Figure 6) and function of FUS and vice versa. It has been reported that the RRM motif and RNA binding mediate the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of RNA binding proteins [54–56]. For instance, a specific RRM motif in TIA [54] and La protein [55] is critical to the nuclear export of the protein. Mutations within the relevant RRM motif caused accumulation of the protein inside the nucleus, similar to our observation. However, it is noted that other RRM motifs may affect the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling differently and cause the redistribution of the protein in cytoplasm [54–56]. Thus, the specific effect of RNA binding on protein subcellular localization needs to be characterized individually. The significance of the RRM domain-mediated subcellular localization in ALS disease is currently under investigation.

FUS is a multi-domain protein that binds to nucleic acids and play a role in diverse processes in gene expression and RNA metabolism [57]. This study reveals a distinct nucleic acid binding mechanism in the RRM domain of FUS. The structural features underline the relatively low binding affinity to nucleic acids with relatively low sequence specificity, which helps understanding its diverse functions. Thousands of RNAs were recently reported as FUS binding targets [48]. In addition, a recent study demonstrated that FUS can bind to the promoter elements of many genes [50]. It is interesting that they found FUS preferentially bind to single strand DNA complementary to potential G-quadruplex sequences. The detailed mechanism of FUS binding to the reported sequences from the genome-wide studies remains to be further investigated. In summary, the insights obtained from our studies of FUS binding to various forms of nucleic acids can help design future studies to better define the role of FUS in ALS.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The structure of the RNA Recognition Motif of FUS is determined.

A unique positively charged “KK” loop is critical to nucleic acid binding.

Substituting the lysine residues in the “KK” loop impaired the nucleic acid binding.

RNA binding deficient mutation altered FUS subcellular localization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Major Basic Research Program of China (2011CB910503), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31070657 and 31021062), and the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KSCX2-YW-R-154 and KSCX2-EW-J-3) to W. F. and W. G.; the National Institutes of Health grant R01NS077284 and the ALS Association grant 6SE340 to H. Z. The NMR spectrometer used in this work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences Protein Science Core Facility Center in the Institute of Biophysics. We thank Dr. Jozsef Gal for critical reading of the manuscript, Dr. Craig Vander Kooi for valuable discussion. We thank Dr. Yingang Feng for help with the 3D NMR data collecting and Yuanyuan Chen for the SPR technical support.

Abbreviations

- FUS

fused in sarcoma

- RRM

RNA Recognition Motif

- NLS

nuclear localization sequence

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- CSP

Chemical shift perturbation

- RNP

ribonucleoprotein

- hnRNP

heteronuclear ribonucleoprotein

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bertolotti A, Lutz Y, Heard DJ, Chambon P, Tora L. hTAF(II)68, a novel RNA/ssDNA-binding protein with homology to the pro-oncoproteins TLS/FUS and EWS is associated with both TFIID and RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 1996;15:5022–5031. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertolotti A, Melot T, Acker J, Vigneron M, Delattre O, Tora L. EWS, but not EWS-FLI-1, is associated with both TFIID and RNA polymerase II: interactions between two members of the TET family, EWS and hTAFII68, and subunits of TFIID and RNA polymerase II complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1489–1497. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou Z, Licklider LJ, Gygi SP, Reed R. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome. Nature. 2002;419:182–185. doi: 10.1038/nature01031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rappsilber J, Ryder U, Lamond AI, Mann M. Large-scale proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome. Genome Res. 2002;12:1231–1245. doi: 10.1101/gr.473902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan AY, Manley JL. TLS inhibits RNA polymerase III transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 30:186–196. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00884-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guipaud O, Guillonneau F, Labas V, Praseuth D, Rossier J, Lopez B, Bertrand P. An in vitro enzymatic assay coupled to proteomics analysis reveals a new DNA processing activity for Ewing sarcoma and TAF(II)68 proteins. Proteomics. 2006;6:5962–5972. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanai Y, Dohmae N, Hirokawa N. Kinesin transports RNA: isolation and characterization of an RNA-transporting granule. Neuron. 2004;43:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law WJ, Cann KL, Hicks GG. TLS, EWS and TAF15: a model for transcriptional integration of gene expression. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2006;5:8–14. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/ell015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vance C, Rogelj B, Hortobagyi T, De Vos KJ, Nishimura AL, Sreedharan J, Hu X, Smith B, Ruddy D, Wright P, Ganesalingam J, Williams KL, Tripathi V, Al-Saraj S, Al-Chalabi A, Leigh PN, Blair IP, Nicholson G, de Belleroche J, Gallo JM, Miller CC, Shaw CE. Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6. Science. 2009;323:1208–1211. doi: 10.1126/science.1165942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwiatkowski TJ, Jr, Bosco DA, Leclerc AL, Tamrazian E, Vanderburg CR, Russ C, Davis A, Gilchrist J, Kasarskis EJ, Munsat T, Valdmanis P, Rouleau GA, Hosler BA, Cortelli P, de Jong PJ, Yoshinaga Y, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Yan J, Ticozzi N, Siddique T, McKenna-Yasek D, Sapp PC, Horvitz HR, Landers JE, Brown RH., Jr Mutations in the FUS/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2009;323:1205–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.1166066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagier-Tourenne C, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. TDP-43 and FUS/TLS: emerging roles in RNA processing and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 19:R46–64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dormann D, Haass C. TDP-43 and FUS: a nuclear affair. Trends Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.05.002. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagier-Tourenne C, Cleveland DW. Rethinking ALS: the FUS about TDP-43. Cell. 2009;136:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calvio C, Neubauer G, Mann M, Lamond AI. Identification of hnRNP P2 as TLS/FUS using electrospray mass spectrometry. RNA. 1995;1:724–733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zinszner H, Sok J, Immanuel D, Yin Y, Ron D. TLS (FUS) binds RNA in vivo and engages in nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 15):1741–1750. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.15.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perrotti D, Bonatti S, Trotta R, Martinez R, Skorski T, Salomoni P, Grassilli E, Lozzo RV, Cooper DR, Calabretta B. TLS/FUS, a pro-oncogene involved in multiple chromosomal translocations, is a novel regulator of BCR/ABL-mediated leukemogenesis. EMBO J. 1998;17:4442–4455. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baechtold H, Kuroda M, Sok J, Ron D, Lopez BS, Akhmedov AT. Human 75-kDa DNA-pairing protein is identical to the pro-oncoprotein TLS/FUS and is able to promote D-loop formation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34337–34342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Arai S, Song X, Reichart D, Du K, Pascual G, Tempst P, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK, Kurokawa R. Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription. Nature. 2008;454:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature06992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lerga A, Hallier M, Delva L, Orvain C, Gallais I, Marie J, Moreau-Gachelin F. Identification of an RNA binding specificity for the potential splicing factor TLS. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6807–6816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahama K, Arai S, Kurokawa R, Oyoshi T. Identification of DNA binding specificity for TLS. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 2009:247–248. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrp124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iko Y, Kodama TS, Kasai N, Oyama T, Morita EH, Muto T, Okumura M, Fujii R, Takumi T, Tate S, Morikawa K. Domain architectures and characterization of an RNA-binding protein, TLS. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44834–44840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morohoshi F, Ootsuka Y, Arai K, Ichikawa H, Mitani S, Munakata N, Ohki M. Genomic structure of the human RBP56/hTAFII68 and FUS/TLS genes. Gene. 1998;221:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prasad DD, Ouchida M, Lee L, Rao VN, Reddy ES. TLS/FUS fusion domain of TLS/FUS-erg chimeric protein resulting from the t(16;21) chromosomal translocation in human myeloid leukemia functions as a transcriptional activation domain. Oncogene. 1994;9:3717–3729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crozat A, Aman P, Mandahl N, Ron D. Fusion of CHOP to a novel RNA-binding protein in human myxoid liposarcoma. Nature. 1993;363:640–644. doi: 10.1038/363640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voigt A, Herholz D, Fiesel FC, Kaur K, Müller D, Karsten P, Weber SS, Kahle PJ, Marquardt T, Schulz JB. TDP-43-Mediated Neuron Loss In Vivo Requires RNA-Binding Activity. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freibaum B, Smith R, Alami N, Taylor PJ. Characterizing the Role of TDP-43 in ALS. Proceedings of the 21st International Symposium on ALS/MND; 2010. p. C6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clery A, Blatter M, Allain FH. RNA recognition motifs: boring? Not quite. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dreyfuss G, Swanson MS, Pinol-Roma S. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles and the pathway of mRNA formation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1988;13:86–91. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(88)90046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikura M, Kay LE, Bax A. A novel approach for sequential assignment of 1H, 13C, and 15N spectra of proteins: heteronuclear triple-resonance three-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. Application to calmodulin. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4659–4667. doi: 10.1021/bi00471a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bax A, Ikura M, Kay LE, Barbato G, Spera S. Multidimensional triple resonance NMR spectroscopy of isotopically uniformly enriched proteins: a powerful new strategy for structure determination. Ciba Found Symp. 1991;161:108–119. doi: 10.1002/9780470514146.ch8. discussion 119–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bax A, Ikura M. An efficient 3D NMR technique for correlating the proton and 15N backbone amide resonances with the alpha-carbon of the preceding residue in uniformly 15N/13C enriched proteins. J Biomol NMR. 1991;1:99–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01874573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR system. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:51–55. 29–32. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gal J, Zhang J, Kwinter DM, Zhai J, Jia H, Jia J, Zhu H. Nuclear localization sequence of FUS and induction of stress granules by ALS mutants. Neurobiol Aging. 32:2323, e2327–2340. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Enokizono Y, Konishi Y, Nagata K, Ouhashi K, Uesugi S, Ishikawa F, Katahira M. Structure of hnRNP D complexed with single-stranded telomere DNA and unfolding of the quadruplex by heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18862–18870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411822200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding J, Hayashi MK, Zhang Y, Manche L, Krainer AR, Xu RM. Crystal structure of the two-RRM domain of hnRNP A1 (UP1) complexed with single-stranded telomeric DNA. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1102–1115. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.9.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuo PH, Doudeva LG, Wang YT, Shen CK, Yuan HS. Structural insights into TDP-43 in nucleic-acid binding and domain interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1799–1808. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li W, Wu P, Ohmichi T, Sugimoto N. Characterization and thermodynamic properties of quadruplex/duplex competition. FEBS Lett. 2002;526:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balagurumoorthy P, Brahmachari SK, Mohanty D, Bansal M, Sasisekharan V. Hairpin and parallel quartet structures for telomeric sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4061–4067. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.15.4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bosco DA, Lemay N, Ko HK, Zhou H, Burke C, Kwiatkowski TJ, Jr, Sapp P, McKenna-Yasek D, Brown RH, Jr, Hayward LJ. Mutant FUS proteins that cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis incorporate into stress granules. Hum Mol Genet. 19:4160–4175. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dormann D, Rodde R, Edbauer D, Bentmann E, Fischer I, Hruscha A, Than ME, Mackenzie IR, Capell A, Schmid B, Neumann M, Haass C. ALS-associated fused in sarcoma (FUS) mutations disrupt Transportin-mediated nuclear import. EMBO J. 2010;29:2841–2857. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xia R, Liu Y, Yang L, Gal J, Zhu H, Jia J. Motor neuron apoptosis and neuromuscular junction perturbation are prominent features in a Drosophila model of Fus-mediated ALS. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2012;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tollervey JR, Curk T, Rogelj B, Briese M, Cereda M, Kayikci M, Konig J, Hortobagyi T, Nishimura AL, Zupunski V, Patani R, Chandran S, Rot G, Zupan B, Shaw CE, Ule J. Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nat Neurosci. 14:452–458. doi: 10.1038/nn.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, Huelga SC, Moran J, Liang TY, Ling SC, Sun E, Wancewicz E, Mazur C, Kordasiewicz H, Sedaghat Y, Donohue JP, Shiue L, Bennett CF, Yeo GW, Cleveland DW. Long pre-mRNA depletion and RNA missplicing contribute to neuronal vulnerability from loss of TDP-43. Nat Neurosci. 14:459–468. doi: 10.1038/nn.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoell JI, Larsson E, Runge S, Nusbaum JD, Duggimpudi S, Farazi TA, Hafner M, Borkhardt A, Sander C, Tuschl T. RNA targets of wild-type and mutant FET family proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1428–1431. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lagier-Tourenne C, Polymenidou M, Hutt KR, Vu AQ, Baughn M, Huelga SC, Clutario KM, Ling SC, Liang TY, Mazur C, Wancewicz E, Kim AS, Watt A, Freier S, Hicks GG, Donohue JP, Shiue L, Bennett CF, Ravits J, Cleveland DW, Yeo GW. Divergent roles of ALS-linked proteins FUS/TLS and TDP-43 intersect in processing long pre-mRNAs. Nature neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nn.3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan AY, Riley TR, Coady T, Bussemaker HJ, Manley JL. TLS/FUS (translocated in liposarcoma/fused in sarcoma) regulates target gene transcription via single-stranded DNA response elements. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:6030–6035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203028109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Couthouis J, Hart MP, Shorter J, Dejesus-Hernandez M, Erion R, Oristano R, Liu AX, Ramos D, Jethava N, Hosangadi D, Epstein J, Chiang A, Diaz Z, Nakaya T, Ibrahim F, Kim HJ, Solski JA, Williams KL, Mojsilovic-Petrovic J, Ingre C, Boylan K, Graff-Radford NR, Dickson DW, Clay-Falcone D, Elman L, McCluskey L, Greene R, Kalb RG, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Ludolph A, Robberecht W, Andersen PM, Nicholson GA, Blair IP, King OD, Bonini NM, Van Deerlin V, Rademakers R, Mourelatos Z, Gitler AD. Feature Article: A yeast functional screen predicts new candidate ALS disease genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109434108. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neumann M, Bentmann E, Dormann D, Jawaid A, DeJesus-Hernandez M, Ansorge O, Roeber S, Kretzschmar HA, Munoz DG, Kusaka H, Yokota O, Ang LC, Bilbao J, Rademakers R, Haass C, Mackenzie IR. FET proteins TAF15 and EWS are selective markers that distinguish FTLD with FUS pathology from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with FUS mutations. Brain. 134:2595–2609. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ticozzi N, Vance C, Leclerc AL, Keagle P, Glass JD, McKenna-Yasek D, Sapp PC, Silani V, Bosco DA, Shaw CE, Brown RH, Jr, Landers JE. Mutational analysis reveals the FUS homolog TAF15 as a candidate gene for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 156B:285–290. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang T, Delestienne N, Huez G, Kruys V, Gueydan C. Identification of the sequence determinants mediating the nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of TIAR and TIA-1 RNA-binding proteins. Journal of cell science. 2005;118:5453–5463. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bayfield MA, Kaiser TE, Intine RV, Maraia RJ. Conservation of a masked nuclear export activity of La proteins and its effects on tRNA maturation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:3303–3312. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00026-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cassola A, Frasch AC. An RNA Recognition Motif Mediates the Nucleocytoplasmic Transport of a Trypanosome RNA-binding Protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:35015–35028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.031633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tan AY, Manley JL. The TET family of proteins: functions and roles in disease. J Mol Cell Biol. 2009;1:82–92. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katahira M, Miyanoiri Y, Enokizono Y, Matsuda G, Nagata T, Ishikawa F, Uesugi S. Structure of the C-terminal RNA-binding domain of hnRNP D0 (AUF1), its interactions with RNA and DNA, and change in backbone dynamics upon complex formation with DNA. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:973–988. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.