Abstract

2-Amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4, 5-b]pyridine (PhIP) is a heterocyclic aromatic amine (HAA) that is formed during the cooking of meat, poultry, and fish. PhIP is a rodent carcinogen and thought to contribute to several diet-related cancers in humans. PhIP is present in the hair of human omnivores but not in the hair of vegetarians. We have now identified PhIP in the fur of fourteen out of sixteen healthy dogs consuming different brands of commercial pet food. The levels of PhIP in canine fur varied by over 85-fold and were comparable to the levels of PhIP present in human hair. However, high density fur containing PhIP covers a very high proportion of the body surface area of dogs, whereas high density terminal hair primarily covers the scalp and pubis body surface area of humans. These findings signify that the exposure and bioavailability of PhIP are high in canines. A potential role for PhIP in the etiology of canine cancer should be considered.

Keywords: Heterocyclic aromatic amines, biomonitoring, carcinogens, canine fur

Introduction

2-Amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4, 5-b]pyridine is a heterocyclic aromatic amine (HAA) that is formed by the reaction of creatine and phenylalanine during the high-temperature cooking of meat, poultry, and fish.1 The concentration of PhIP can reach up to 480 parts per billion (ppb) in well-done cooked poultry,2 and PhIP has been estimated to comprise about 70% of the daily mean intake of HAAs in the United States.3 PhIP is a multisite carcinogen in rodents and induces lymphoma, as well as tumors of the colorectum, pancreas, prostate, and female mammary gland.4 A number of epidemiological studies have reported that the frequent consumption of well-done cooked meats containing PhIP and other HAAs increases the risk of developing cancer at some of these target sites in humans.5 Moreover, the National Toxicology Report 11th Edition concluded that PhIP is reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen.6 Therefore, the frequent consumption of well-done cooked meats containing high levels of HAAs is a public health concern.

There is a paucity of data on the formation of heat-processed carcinogens in pet foods. There is one report in the literature on the presence of mutagens and the identification of HAAs in commercial pet foods.7 PhIP was identified as the major HAA formed in pet foods: it occurred at levels ranging from less than 1 ppb up to 70 ppb.7 Because the canine diet is regimented, the exposure to PhIP and its deleterious biological effects in the dog may be considerably greater than in humans, where the diet is wide-ranging with many foods that do not contain PhIP. Moreover, dogs are exposed to PhIP in utero, and the exposure to PhIP continues when the pups are rapidly growing, a time period when the animals may be most susceptible to mutations induced by PhIP, and the exposure to PhIP remains throughout the life time of the animal. It is plausible that PhIP may contribute to the etiology of some types of canine cancers.

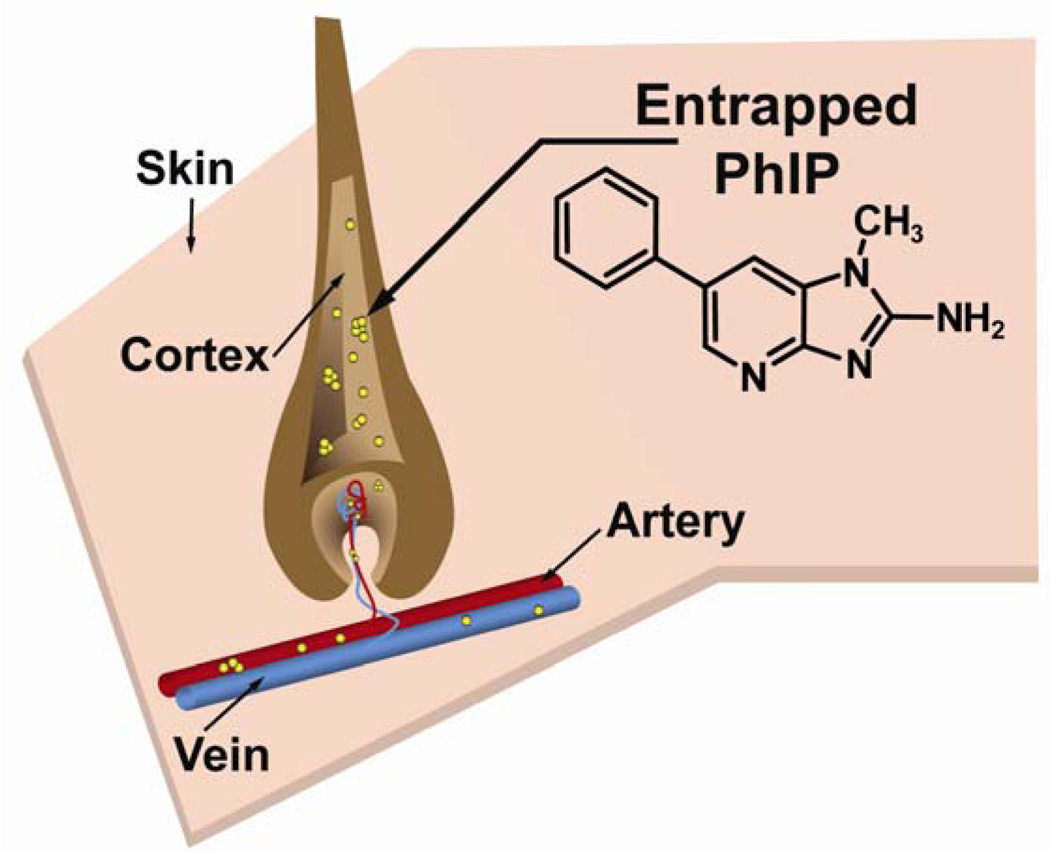

Certain drugs and carcinogens, including PhIP, bind with high affinity to proteins and pigments in the hair follicle and become entrapped within the hair-shaft during hair growth (Figure 1).8–11 The biomonitoring of PhIP in hair is a potentially more accurate estimate of chronic dietary exposure9,11,12 than the inferences obtained from food frequency questionnaires that are often used in molecular epidemiology studies.13 We have previously shown that PhIP is present in hair of omnivores but not in hair of vegetarians.11 In this current study, we have examined for the presence of PhIP in the fur of healthy dogs consuming different brands of commercial pet food.

Figure 1.

The PhIP biomarker in hair /fur.

Experimental Procedures

Caution: PhIP is a carcinogen and should be handled in a well-ventilated fume hood with the appropriate protective clothing.

PhIP and its trideuterated derivative 1-[2H3C]-PhIP (isotopic purity >99%) were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Ontario, Canada). Oasis MCX LP extraction cartridges (30 and 150 mg) were purchased from Waters (Milford, MA), Celite 535 was purchased from EMD Chemicals (Gibbs Town, NJ). All other reagents and solvents were of ACS grade or higher.

Dog Subjects and Fur Specimens

Healthy pet dogs were recruited through the Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, or from one investigator at the Wadsworth Center. The only samples obtained from the dogs were fur brushings or clippings, which were determined to be exempt from IACUC approval. The dog owners were interviewed for the dietary and health history of the animals. The animals chosen for participation in this study were on regimented commercial diets for a minimum of three months and did not consume cooked meats or leftover scraps prepared for human consumption. Fur samples were obtained by brushing or clipping the dogs’ fur on their back and close to their hind quarters. The samples (0.25–2.0 g) were collected into plastic zip-lock bags and stored at 4 °C until processed. White fur samples were also obtained from the mane of the Bernese Mountain Dogs.

Human Hair Collection

Volunteers from Albany, New York, were recruited and asked whether they eat meat on a regular basis (“meat-eaters”; n = 6) or not (“vegetarians”, n = 6). The clippings of hair from volunteers were obtained when the subjects went to their local barbers to get their hair cut. The subjects were nonsmokers and did not use hair dyes. The hair samples (0.25–2.0 g) were collected in plastic zip-lock bags and stored at −20 °C until processed. The samples were rendered anonymous (designated as meat-eater or vegetarian). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Wadsworth Center.

Isolation of PhIP from Canine Fur and Human Hair

The fur or hair samples were minced with electric clippers to lengths of several millimeters. The minced hair samples (50 mg) were placed in Eppendorf tubes and prewashed with 0.1N HCl (1 mL) by vortexing for 30 s, followed by centrifugation and removal of the solvent. This wash procedure was repeated three times. Then, the hair was washed with CH3OH (1 mL) 3 times, using the same procedure. The hair was allowed to dry in a ventilated hood for 30 min to evaporate the residual CH3OH. The hair was mixed with 1N NaOH (0.5 mL) and 100 pg internal standard ([2H3C]-PhIP) and was heated at 80 °C for 1 h (human hair) or 2 h (canine fur). After the digested hair or fur matrix was cooled, the PhIP was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 0.9 mL). The organic extract was then acidified with CH3CO2H (30 µL). A Waters Oasis MCX cartridge (30 mg), which was attached to a vacuum manifold under slight pressure (~5 inches of Hg) to achieve a flow rate of the eluent of approximately 1 mL/min, was prewashed with 5% NH4OH in CH3OH (1 mL) and 2% CH3CO2H in CH3OH (1 mL). The ethyl acetate extracts were then applied to the MCX cartridge. The cartridges were washed with 0.1N HCl in 40% CH3OH (1 mL), followed by CH3OH (1 mL), H2O (1 mL) and 5% NH4OH in 45% H2O / 50% CH3OH (2 mL). PhIP was eluted from the resin with CH3OH containing 5% NH4OH (1.5 mL), and the eluent was concentrated to approximately 0.1 mL, by vacuum centrifugation. Then, the samples were transferred into silylated glass conical vials and evaporated to dryness by vacuum centrifugation. The samples were resuspended in 10% DMSO:90% H2O (40 µL).

Spectrophotometric Characterization of Melanin in Fur or Hair

Fur (1 – 5 mg) was digested in a mixture of the detergent Soluene 350:H2O (9:1 v/v, 1 mL), by heating at 95 °C for 1 h. Upon cooling, the spectra were recorded over the wavelength range of 400 to 800 nm with an Agilent 8453 model UV/VIS spectrophotometer. The absorbance at 500 nm is an estimate of the total amount of melanin (eumelanin and pheomelanins).14 The estimate of total melanin content was based on the absorbance at 500 nm, assuming 100 µg melanin/mL corresponds to an absorbance value of 1.00 at 500 nm.14

UPLC-ESI/MS/MS Analyses

Chromatography was performed with a NanoAcquity UPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) equipped with a Michrom C18 column (0.3 × 150 mm, 3 µm particle size, Michrom Bioresources Inc., Auburn, CA). The A solvent was 0.025% HCO2H in H2O, and the B solvent contained 0.025% HCO2H and 5% H2O in CH3CN. The flow rate was set at 5 µL/min, starting at 95% A increased by a linear gradient to 60% B in 10 min, and then to 99% B at 11 min holding for 1 min. The gradient was reversed to the 95% A over 1 min and a post-run time of 4 min was required for re-equilibration. The manipulation of UPLC system was done by MassLynx software (Waters Corp., Milford, MA). The mass-spectral data were acquired on a Finnigan™ Quantum Ultra Triple Stage Quadrupole MS (TSQ/MS) (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA) and processed with Xcalibur version 2.07 software.

Analyses were conducted in the positive ionization mode and employed an Advance CaptiveSpray source from Michrom Bioresources. The spray voltage was set at 2000 V; the in-source fragmentation was −5 V; and the capillary temperature was 200 °C. There was no sheath or auxiliary gas. The peak widths (in Q1 and Q3) were set at 0.7 Da, and the scan width was 0.002 Da. The following transitions and collision energies were used for the quantification of PhIP and its internal standard: PhIP and [2H3C]-PhIP: 225.1 → 210.1 and 228.1 → 210.1 at 35 eV. The dwell time for each transition was 5 ms. Argon was used as the collision gas and was set at 1.5 mTorr. Product ion spectra were acquired on the protonated molecule [M+H]+, scanning from m/z 100 to 250 at a scan speed of 250 amu/s using 30 eV ramp energy and the same acquisition parameters as above. The quantification of PhIP in fur was done with an external calibration curve. The performance of the analytical method was reported previously.11

Results

Identification of PhIP in Canine Fur

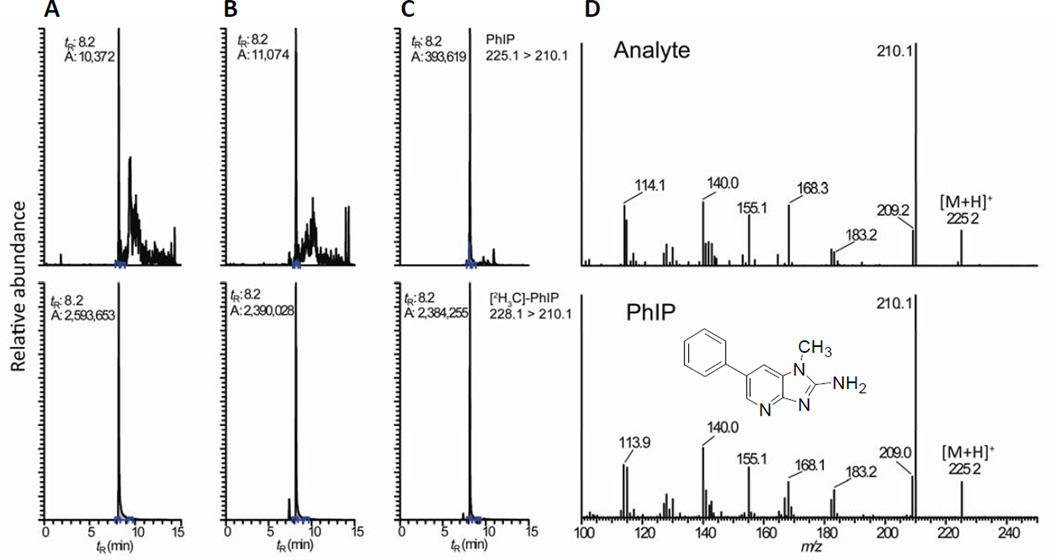

The analysis of PhIP was conducted on fur samples from 16 healthy dogs. The mass chromatograms of PhIP recovered from the fur of dog 3, a mixed-breed dog, and dog 11, a Bernese Mountain Dog, are shown in Figure 2. Both white and black-pigmented fur of the Bernese Mountain Dog were analyzed (Figure 3). The limit of quantification (LOQ) of the assay, defined as the background noise + 10*SD,15 was estimated at 35 pg PhIP per g fur. The level of PhIP in the fur of the mixed-breed was below the LOQ value, whereas PhIP was found at a level of 350 pg/g in the black fur of the Bernese Mountain Dog. The identity of PhIP was confirmed by its full scan product ion spectrum, which was in excellent agreement to the spectrum of the synthetic standard (Figure 2D). However, the content of PhIP was below the LOQ in the white fur of the same dog. PhIP is known to have a high binding affinity for eumelanin, a pigment that is more predominant in black hair than in lighter-colored hair.9,16 The presence of PhIP in black fur and its absence from the white fur of the same animal is consistent with the notion that pigmentation is critical for the binding of this carcinogen to fur.

Figure 2.

Mass chromatograms of PhIP in (A) fur of the mix-breed dog #3, (B) white fur and (C) black fur of the Bernese Mountain Dog #11. The trace amounts of PhIP detected in the mixed breed’s fur and the white fur of the Bernese Mountain Dog are due to the residual unlabeled PhIP present in the isotopically labeled [2H3C]-PhIP internal standard, which was 99% isotopically pure. The symbol tR represents retention time, and the symbol A represents area counts. The product ion spectra of PhIP detected in the black fur and synthetic PhIP, following background subtraction, are presented in panel D.

Figure 3.

The white and black fur of dog #11, Moses, were assayed for PhIP.

Estimates of PhIP in Canine Fur and Human Hair

The levels of PhIP expressed per gram of fur from 16 dogs are reported in Table 1. The levels ranged from less than 35 up to 505 pg/g fur: 14 out of the 16 dogs were positive for PhIP. The levels of PhIP are also reported per mg of melanin, since this pigment has high binding affinity for PhIP.9

Table 1.

Binding of PhIP to Canine Fur

| Dog | Breed | Age (yr) |

Gender | Fur color | PhIP (pg/g fur) |

PhIP (ng/g melanin) |

Melanin (mg/g fur) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bernese Mountain Dog | 8.5 | Male | Black | 266 | 4.6 | 56 |

| 2 | Labrador Retriever | 2 | Male | Black | 184 | 3.1 | 59 |

| 3 | Mix-breeds | 1 | Male | Yellow/brown | < 35 | - | 25 |

| 4 | Mix-breeds | 9 | Male | Black | 241 | 4.0 | 60 |

| 5 | Mix-breeds | 13 | Female | Black | 292 | 6.5 | 43 |

| 6 | Mix-breeds | 6 | Female | Dark gray /white | 208 | 7.4 | 29 |

| 7 | Cavalier King Charles Spaniel | 6 | Female | Red/brown | 35 | 2.1 | 17 |

| 8 | Yorkshire Terrier | 3 | Female | Brown/tan | 440 | 16.8 | 24 |

| 9 | Labrador Retriever | 0.5 | Female | Black | 231 | 5.7 | 38 |

| 10 | Labrador Retriever | 3 | Female | Black | 505 | 10.4 | 48 |

| 11* | Bernese Mountain Dog | 0.5 | Male | Black | 3000 | 30.6 | 98 |

| 11** | Bernese Mountain Dog | 3.5 | Male | White | < 35 | - | 4.5 |

| 11** | Bernese Mountain Dog | 3.5 | Male | Black | 351 | 3.8 | 92 |

| 12 | Bernese Mountain Dog | 1 | Female | Black | 383 | 4.1 | 92 |

| 13 | Gordon Setter | 12 | Male | Black/tan | 126 | 2.2 | 58 |

| 14 | Cavalier King Charles Spaniel | 10 | Male | Yellow/brown | < 35 | - | 11 |

| 15 | Bernese Mountain Dog | 5 | Female | Black | 760 | 4.1 | 96 |

| 16 | Bernese Mountain Dog | 7 | Female | Black | 745 | 4.1 | 94 |

Dog was 6 months of age,

same dog but 3.5 years of age

Duplicate measurements and values were within 10% of each other

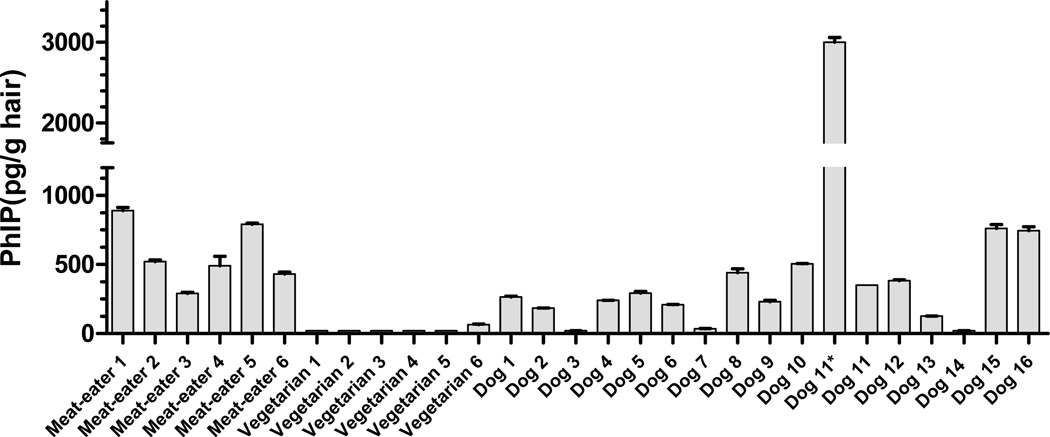

We have compared the levels of PhIP found in dog fur to those levels present in hair of human volunteers on non-restricted diets. The levels of contamination of PhIP in fur and hair are summarized in Figure 4. All of the human omnivores contained PhIP in their hair, whereas only 1 out of the six vegetarians contained PhIP in their hair, and that one subject harbored levels of PhIP just above the LOQ value. Thus, the exposure to PhIP is prevalent both in dogs and human omnivores, and the levels of PhIP present in canine fur and hair of omnivores are comparable. It is worthy to note that dog 11 harbored very high levels of PhIP in his fur at the age of 6 months, and the level of PhIP dropped by 9-fold when he was an adult (aged 4 years). Anectdotally, the changes in PhIP levels in fur could be attributed to a change in the dog’s diet over this time period, or possibly due to a change in the efficiency of the first pass metabolism of PhIP in the liver, where less PhIP is present in plasma and available to bind to fur. The analysis of PhIP in fur from a larger number of canines at different stages of their lifetimes with defined diets is required to identify the factors that influence the binding of PhIP to fur.

Figure 4.

PhIP levels in hair of human omnivores and vegetarians, and fur of 16 canines. Dog 11 was assayed for PhIP at the age of 4 months* and at the age of 4 years. The human data was adapted from reference 11.

Discussion

PhIP is a ubiquitous genotoxicant that is present in many cooked proteinaceous foods.1 The amount of PhIP and other HAAs formed in cooked meats is highly dependent on the type of meat cooked, as well as the method, temperature, and duration of cooking; these variable parameters can lead to differences in the concentration of PhIP by more than 100-fold.1,17,18 In a previous study, 14 pet food samples were analyzed for HAAs and 10 out of the 14 pet foods were found to contain PhIP.7 The levels of PhIP formed ranged from less than 1 ppb up to 70 ppb. Moreover, the heating of a mixture of meat ingredients and grains at higher temperatures used for the extrusion process to create dried dog food or kibbles may produce PhIP, which forms directly by heating phenylalanine with creatine.1 Another carcinogenic HAA, 2-amino-3,8-dimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (MeIQx), was also frequently identified in pet foods, but the concentrations were lower and ranged from 0.2 to 3.3 ng/g.7 Some processed meat flavors and meat extracts contain mutagenic HAAs at elevated levels.19–21 These flavoring agents can be used in pet foods and treats and add to the daily exposure to PhIP and possibly other HAAs. All of the dogs in our study, except for the mixed-breed (dog 3) and the Gordon Setter (dog 13), consumed a protein-based diet containing chicken in kibble form. Well-done cooked chicken is known to contain some of the highest levels of PhIP in cooked meats.1,18 A systematic study of pet food ingredients and the processing conditions may identify the source(s) and permit ways to minimize the occurrence of PhIP in pet foods

The pet foods and treats consumed by our dog subjects were highly varied and the intake of PhIP was likely to have ranged widely. We found that the levels of PhIP present in canine fur varied by over 85-fold, when expressed as PhIP bound per g fur, and dark-pigmented fur sequestered higher levels of PhIP than light colored fur. These amounts of PhIP in fur are comparable to the range in levels of PhIP bound to hair of human omnivores. However, high density fur of variable length contaminated with PhIP covers approximately 90% of the body surface area of dogs, whereas high density terminal hair covers significantly less of the body surface area of humans, encompassing primarily the scalp and pubis. The follicular binding data suggest that the exposure to PhIP is greater in canines on a regimented diet of commercial pet food than the exposure to PhIP in humans on a free-choice diet, although interspecies differences in first pass hepatic metabolism or the intricate vascular system surrounding the hair follicles may influence the level of binding of PhIP to fur or hair.

Dogs are susceptible to the genotoxic effects of aromatic amines, a class of carcinogenic chemicals structurally related to HAAs.22 In fact, the dog was the first successful animal model established for human bladder cancer, where dogs exposed to 2-naphthylamine (2-NA) developed bladder tumors.23 Subsequent studies showed that N-oxidation of 2-NA played a critical role in the initiation of bladder cancer in the same animal model.24 The bioactivation pathway of 2-NA is catalyzed by cytochrome P450, which is the same enzyme that is involved in the conversion of PhIP into a carcinogenic metabolite.22

Much research has been devoted to assessing the health hazards associated with consuming heat-processed carcinogens in the diet and human cancer risk.1,4,5 However, knowledge about the formation of carcinogens produced in heat-processed pet foods is lacking, and epidemiological studies on dietary risk of factors and consumption of heat-processed pet foods in the development of canine cancer are largely unexplored.25–27 There are believed to be multiple causes for cancer in humans and likely for pets as well.28 A lifelong exposure to PhIP, a genotoxicant and rodent carcinogen,4 may be a plausible contributing cause to human and canine cancers.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Animal Cancer Care and Research Program of the University of Minnesota for support, and Dr. Stephen Hecht, Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, MN, for his intellectual contributions to this study.

Funding Source: This research was supported by grant R01 CA122320 (D.G. and R.J.T.).

Footnotes

Notes: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Reference List

- 1.Felton J, Jagerstad M, Knize M, Skog K, Wakabayashi K. Contents in foods, beverages and tobacco. In: Nagao M, Sugimura T, editors. Food Borne Carcinogens Heterocyclic Amines. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2000. pp. 31–71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinha R, Rothman N, Brown E, Salmon C, Knize M, Swanson C, Rossi S, Mark S, Levander O, Felton J. High concentrations of the carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) occur in chicken but are dependent on the cooking method. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4516–4519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keating G, Bogen K. Estimates of heterocyclic amine intake in the US population. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2004;802:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K, Nakagama H, Nagao M. Heterocyclic amines: Mutagens/carcinogens produced during cooking of meat and fish. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:290–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng W, Lee S. Well-done meat intake, heterocyclic amine exposure, and cancer risk. Nutr. Cancer. 2009;61:437–446. doi: 10.1080/01635580802710741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Toxicology Program Report on Carcinogenesis. Eleventh Edition. Research Triangle Park, N.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knize M, Salmon C, Felton J. Mutagenic activity and heterocyclic amine carcinogens in commercial pet foods. Mutat. Res. 2003;539:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(03)00164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakahara Y, Takahashi K, Kikura R. Hair analysis for drugs of abuse. X. Effect of physicochemical properties of drugs on the incorporation rates into hair. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1995;18:1223–1227. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander J, Reistad R, Hegstad S, Frandsen H, Ingebrigtsen K, Paulsen J, Becher G. Biomarkers of exposure to heterocyclic amines: approaches to improve the exposure assessment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002;40:1131–1137. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gratacos-Cubarsi M, Castellari M, Valero A, Garcia-Regueiro JA. Hair analysis for veterinary drug monitoring in livestock production. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2006;834:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bessette E, Yasa I, Dunbar D, Wilkens L, Marchand L, Turesky R. Biomonitoring of carcinogenic heterocyclic aromatic amines in hair: A validation study. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009;22:1454–1463. doi: 10.1021/tx900155f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi M, Hanaoka T, Tsugane S. Validity of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire in the assessment of heterocyclic amine intake using 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) levels in hair. Mutat. Res. 2007;630:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristal A, Peters U, Potter J. Is it time to abandon the food frequency questionnaire? Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2826–2828. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-ED1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozeki H, Ito S, Wakamatsu K, Thody AJ. Spectrophotometric characterization of eumelanin and pheomelanin in hair. Pigment Cell Res. 1996;9:265–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1996.tb00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacDougall D, Amore F, Cox G, Crosby D, Estes F, Freeman D, Gibbs W, Gordon G, Keith L, Lal J, Langner R, McClelland N, Phillips W, Pojasek R, Sievers R. Guidelines for data acquistion and data quality evaluation in environmental chemistry. Anal. Chem. 1980;52:2242–2249. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reistad R, Nyholm S, Huag L, Becher G, Alexander J. 2-Amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) in human hair as biomarker for dietary exposure. Biomarkers. 1999;4:263–271. doi: 10.1080/135475099230796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ni W, McNaughton L, LeMaster D, Sinha R, Turesky R. Quantitation of 13 heterocyclic aromatic amines in cooked beef, pork, and chicken by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization/tandem mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:68–78. doi: 10.1021/jf072461a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skog K, Solyakov A. Heterocyclic amines in poultry products: a literature review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2002;40:1213–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stavric B, Lau B, Matula T, Klassen R, Lewis D, Downie R. Mutagenic heterocyclic aromatic amines (HAAs) in 'processed food flavour' samples. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1997;35:185–197. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(96)00119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solyakov A, Skog K, Jagerstad M. Heterocyclic amines in process flavours, process flavour ingredients, bouillon concentrates and a pan residue. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(98)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aeschbacher H, Turesky R, Wolleb U, Wurzner HP, Tannenbaum SR. Comparison of the mutagenic activity of various brands of food grade beef extracts. Cancer Lett. 1987;38:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(87)90203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turesky R, Le Marchand L. Metabolism and biomarkers of heterocyclic aromatic amines in molecular epidemiology studies: lessons learned from aromatic amines. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011;24:1169–1214. doi: 10.1021/tx200135s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hueper W, Wiley F, Wolfe H. Experimental production of bladder tumors in dogs by administration of beta-naphthylamine. J. Industrial Hygiene. 1938;20:46–84. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radomski J, Brill E. Bladder cancer induction by aromatic amines: role of N-hydroxy metabolites. Science. 1970;167:992–993. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3920.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelsey J, Moore A, Glickman L. Epidemiologic studies of risk factors for cancer in pet dogs. Epidemiol. Rev. 1998;20:204–217. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonnenschein E, Glickman L, Goldschmidt MH, McKee LJ. Body conformation, diet, and risk of breast cancer in pet dogs: a case-control study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1991;133:694–703. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alenza D, Rutteman G, Pena L, Benyen A, Cesta P. Relation between habitual diet and canine mammary tumors in a case-control study. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 1998;12:132–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1998.tb02108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loeb L, Harris C. Advances in chemical carcinogenesis: a historical review and prospective. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6863–6872. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]