Abstract

Background: Chronic persistent low back and lower extremity pain secondary to central spinal stenosis is common and disabling. Lumbar surgical interventions with decompression or fusion are most commonly performed to manage severe spinal stenosis. However, epidural injections are also frequently performed in managing central spinal stenosis. After failure of epidural steroid injections, the next sequential step is percutaneous adhesiolysis and hypertonic saline neurolysis with a targeted delivery. The literature on the effectiveness of percutaneous adhesiolysis in managing central spinal stenosis after failure of epidural injections has not been widely studied.

Study Design: A prospective evaluation.

Setting: An interventional pain management practice, a specialty referral center, a private practice setting in the United States.

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of percutaneous epidural adhesiolysis in patients with chronic low back and lower extremity pain with lumbar central spinal stenosis.

Methods: Seventy patients were recruited. The initial phase of the study was randomized, double-blind with a comparison of percutaneous adhesiolysis with caudal epidural injections. The 25 patients from the adhesiolysis group continued with follow-up, along with 45 additional patients, leading to a total of 70 patients. All patients received percutaneous adhesiolysis and appropriate placement of the Racz catheter, followed by an injection of 5 mL of 2% preservative-free lidocaine with subsequent monitoring in the recovery room. In the recovery room, each patient also received 6 mL of 10% hypertonic sodium chloride solution, and 6 mg of non-particulate betamethasone, followed by an injection of 1 mL of sodium chloride solution and removal of the catheter.

Outcomes Assessment: Multiple outcome measures were utilized including the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), the Oswestry Disability Index 2.0 (ODI), employment status, and opioid intake with assessment at 3, 6, and 12, 18 and 24 months post treatment. The primary outcome measure was 50% or more improvement in pain scores and ODI scores.

Results: Overall, a primary outcome or significant pain relief and functional status improvement of 50% or more was seen in 71% of patients at the end of 2 years. The overall number of procedures over a period of 2 years were 5.7 ± 2.73.

Limitations: The lack of a control group and a prospective design.

Conclusions: Significant relief and functional status improvement as seen in 71% of the 70 patients with percutaneous adhesiolysis utilizing local anesthetic steroids and hypertonic sodium chloride solution may be an effective management strategy in patients with chronic function limiting low back and lower extremity pain with central spinal stenosis after failure of conservatie management and fluoroscopically directed epidural injections.

Keywords: Central spinal stenosis, percutaneous adhesiolysis, steroids, local anesthetics, hypertonic sodium chloride solution

Introduction

Central spinal stenosis is the narrowing of the spinal canal with encroachment on the neural structures by surrounding bone and soft tissues prevalent in 27.2% of the population 1,2. Spinal stenosis may, however, be asymptomatic in many cases despite radiological diagnosis 3,4. Symptoms of central spinal stenosis may be related to a neurovascular mechanism such as reduced arterial flow in cauda equina, venous congestion, and increased epidural pressure 5-13, nerve root excitation by local inflammation, or direct compression in the central canal 5,10. Consequently, spinal stenosis is a multifactorial disorder and clinical presentation can be variable with or without neurogenic claudication manifested by pain in the buttocks or legs when walking, which disappears with sitting or lumbar flexion 5,11,12. There is no gold standard or valid diagnostic test for concluding that spinal stenosis is the cause of pain in a given patient 13. In fact, a systematic literature review 14 of the quantitative radiologic criteria for the diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis of 25 studies reporting on radiological signs of lumbar spinal stenosis and 4 systematic reviews related to the evaluation of different treatments showed 10 different parameters identified to quantify lumbar spinal stenosis. Spinal stenosis is the most common reason for lumbar spine surgery in persons older than 65 years in the United States 15-23. The failure of conservative management leads to decompressive surgery with or without fusion. A systematic review comparing surgery versus conservative treatment for symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis 5 concluded that in patients with symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis, the implantation of a specific type of device or decompressive surgery, with or without fusion, is more effective than continued conservative treatment when the latter has failed for 3 to 6 months. However, in this systematic review, epidural steroids and adhesiolysis were not properly assessed.

In another systematic review describing non-operative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis in patients with neurogenic claudication 17, the authors concluded that there was very low quality evidence from a single trial that epidural steroid injections improve pain, function, and quality of life for up to 2 weeks when compared with home exercise or inpatient physical therapy. There were no adhesiolysis studies included. Consequently, they concluded that moderate- and high-grade evidence for non-operative treatment was lacking and thus prohibiting recommendations to guide clinical practice. Once again, the authors did not utilize the available studies in evidence synthesis, leading to unfounded conclusions. The improper evaluation of available literature in managing spinal stenosis with epidural injections was also illustrated in a protocol for lumbar epidural steroid injections for spinal stenosis 12. However, recent systematic reviews performed showed fair evidence for managing central lumbar spinal stenosis with caudal, interlaminar, and transforaminal epidural injections and percutaneous adhesiolysis 24-27. Furthermore, there have been multiple publications showing evidence of the effectiveness of epidural injections in managing spinal stenosis 28-31.

Thus, spinal stenosis is commonly managed by various conservative modalities, interventional techniques, and surgical interventions 5,15-45. Since the relief from epidural injections is only modest in patients suffering from spinal stenosis, the next alternative is percutaneous adhesiolysis. A preliminary report of percutaneous adhesiolysis in patients with central lumbar stenosis after failure of fluoroscopically directed caudal epidural injections evaluating 50 patients showed significant improvement in 76% of patients undergoing percutaneous adhesiolysis. However, this study was hampered by a small sample size 32. Caudal epidural steroid injections have been shown to be with significant improvement in approximately 50% of the patients 25,28; however, a preliminary report 29 of lumbar interlaminar epidural injections in central spinal stenosis showed better results with a small sample size. It remains to be seen if these results continue to be maintained with subsequent follow-up with appropriate sample sizes. Percutaneous adhesiolysis is employed to facilitate targeted delivery and has been shown in multiple publications to be effective in post surgery syndrome 27,43-46.

This study is undertaken to evaluate the role of percutaneous adhesiolysis with hypertonic sodium chloride solution in patients with chronic intractable pain secondary to lumbar central spinal stenosis. This study is a continuation of preliminary results of a randomized trial 32 with 25 patients followed prospectively for 2 years, along with additional 45 patients prospectively evaluated for 2 years.

Materials and Methods

The initial part of the study was conducted according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines 47. The study was performed in an interventional pain management practice, a specialty referral center, in the United States, in a private practice setting. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and was registered on the U.S. Clinical Trial Registry with an assigned number of NCT00370994. This study was conducted with internal resources of the practice without any external funding either from industry or from elsewhere.

The study was designed to assess 120 patients with 60 patients in each group. The randomized portion was conducted over a period of one year with the publication of preliminary results with 25 patients in each group 32. However, due to the difficulties of recruiting patients into a double-blind randomized trial with a high unblinding or withdrawal rate, 25 patients in the intervention group receiving percutaneous adhesiolysis were unblinded and were subsequently followed for 2 years. In addition, 45 patients were recruited into the prospective observational phase of the study with a total of 70 patients.

Patients

All patients were drawn from a single pain management practice. All patients signed an appropriate informed consent to participate in the study.

Pre-Enrollment Evaluation

The pre-enrollment evaluation included demographic data, medical and surgical history with coexisting disease(s), radiologic investigations, physical examination, pain rating scores using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), work status, opioid intake, and functional status assessment by the Oswestry Disability Index 2.0 (ODI).

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of lumbar central spinal stenosis with radicular pain, patients over the age of 30 years; patients with a history of chronic function-limiting low back pain and lower extremity pain of at least 6 months duration; and patients who were competent to understand the study protocol and provide voluntary, written informed consent and participate in outcome measurements.

Further inclusion criteria included patients who have failed to improve substantially with conservative management including, but not limited to, physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, exercises, drug therapy, and bed rest. All these patients had also failed to respond appropriately to fluoroscopically directed epidural injections.

Exclusion criteria were history of previous surgery, foraminal stenosis, uncontrollable or unstable opioid use, uncontrolled psychiatric disorders, uncontrolled medical illness, either acute or chronic, any conditions that could interfere with the interpretation of the outcome assessments, pregnant or lactating women, and patients with a history or potential for adverse reaction(s) to local anesthetics or steroids.

Description of Interventions

After the identification of filling defects, the Racz catheter was advanced through the RK needle (Epimed International, Farmers Branch, TX, USA) to the area of the filling defect or the site of stenosis as determined by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), or symptomatology. Appropriate adhesiolysis was carried out and the final positioning was achieved in the epidural space and into the lateral and ventral epidural space. After satisfactory positioning, at least 3 to 5 mL of contrast was injected. If there was no subarachnoid, intravascular, or other extra-epidural filling and satisfactory filling was obtained with epidural and targeted nerve root filling, 5 mL of 2% preservative free Xylocaine was injected.

In the recovery room, after 10 to 15 minutes of monitoring, an injection of sodium chloride solution 10% was administered by repeated injections in doses of 3 mL twice, followed by an injection of 6 mg of nonparticulate betamethasone and 1 mL of sodium chloride solution with the removal of the catheter. The patient was ambulated if all parameters were satisfactory. Intravenous access was removed and the patient was discharged home with appropriate instructions. Repeat percutaneous adhesiolysis injections were provided based on the response to the prior injection as evaluated by improvement in physical and functional status, followed by increased levels of pain being reported and deteriorating relief and/or a deterioration in functional status below 50%.

Co-Interventions

Most patients were receiving opioid and non-opioid analgesics as well as adjuvant analgesics. Some were involved in a therapeutic exercise program. All patients continued previously directed exercise programs, as well as their work. Thus, in this study, there was no specific physical therapy, occupational therapy, bracing, or other interventions offered other than the study intervention.

Objectives

The study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of percutaneous adhesiolysis in managing chronic low back and lower extremity pain in patients with lumbar central spinal stenosis by providing effective and long-lasting pain relief over a period of 2 years.

Outcomes

Multiple outcome measures were utilized including the NRS (0-10 scale) pain scale, the ODI on a 0-50 scale, employment status, and opioid intake in terms of morphine equivalents, with assessment at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-treatment. The NRS represented no pain with a 0 and the worst pain imaginable with a 10. The ODI was utilized for functional assessment. The value and validity of the NRS and ODI have been reported 48,49.

The primary outcome measure was at least 50% improvement of NRS and ODI scores.

Based on the dosage frequency and schedule of the drug, the opioid intake was converted to morphine equivalents 50.

Rather than including all of the patients participating in the study as employable, employment and work status were determined based on employability at the time of enrollment. Employment and work status were classified into multiple categories such as employable, housewife with no desire to work outside the home, retired, or over the age 65. Patients who were unemployed due to pain, or employed but on sick leave or laid off but actively pursuing employment opportunities, were considered as employable.

Multiple thresholds for clinically important differences in the evaluation of NRS and ODI have been described 24-27,49,51-53. For this evaluation, a robust measure of significant improvement with 50% pain relief and reduction in disability scores was utilized 28,29,54-63.

Statistical Methods

For testing the differences in proportions, chi-squared statistic was used. Wherever the expected value was less than 5, Fisher's exact test was used; a paired t-test was used to compare the pre- and post treatment. Because the outcome measures of the participants were measured at 6 points in time, repeated measures analysis of variance were performed with the post hoc analysis. A P value of 0.05 was considered as significant.

Intent-to-Treat-Analysis

An intent-to-treat-analysis was performed. Either the last follow-up data or initial data was utilized in the patients who dropped out of the study, and no other data were available.

Results

Participant Flow

A total of 70 patients were included. Of these, 25 patients were from the randomized, controlled percutaneous adhesiolysis trial whereas the remaining 45 patients were recruited in the observational phase. Of the 70 patients, one patient died after 18 months, one patient withdrew from the study, one patient moved away, one patient was discharged due to drug abuse, one patient was lost to follow-up. Furthermore, 8 patients were nonresponsive or moved to medical therapy due to other reasons or lack of their interest in undergoing further treatments with the percutaneous adhesiolysis. Overall, 7 patients had no follow-up after the first or second visit. Consequently, the data was extrapolated with intent-to-treat analysis in 20 patients at various periods.

Ten of the 70 patients received only one or 2 treatments due to failure to respond appropriately.

Recruitment

The recruitment period lasted from January 2006 to June 2010.

Baseline Data

Demographic and clinical characteristics are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical data.

| Number (70) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 43% (30) |

| Female | 57% (40) | |

| Age | Mean ± SD | 57.2 ± 13.7 |

| Height (inches) | Mean ± SD | 66.5 ± 3.9 |

| Weight (lbs) | Mean ± SD | 181.2 ± 48.1 |

| Pain Duration (months) | Mean ± SD | 144.1 ± 136.3 |

| Mode of onset of Pain | Non-traumatic | 77% (54) |

| Traumatic | 23% (16) | |

| Baseline Average Pain Score | Mean ± SD | 8.0 ± 0.83 |

| Baseline Oswestry Disability Index | Mean ± SD | 31.1 ± 4.10 |

| Back Pain Distribution | Bilateral | 85% (59) |

| Left or Right | 15% (11) | |

| Leg Pain Distribution | Bilateral | 50% (35) |

| Left or Right | 50% (35 | |

| Spinal stenosis severity | Mild | 27% (19) |

| Moderate | 36% (25) | |

| Severe | 37% (26) |

Therapeutic Procedural Characteristics

Therapeutic procedural characteristics with average pain relief per procedure are illustrated in Table 2. The average pain relief per procedure was 13.2 ± 12.6 weeks. The average number of procedures was 3 to 4 per year, and 5 to 6 for 2 years. Total relief for 2 years was 71.1 ± 37.4 weeks over a period of 104 weeks. Only 2 patients received long-term relief with one patient with one treatment with 2 years of relief, and another patient with 2 treatments with 2 years of relief.

Table 2.

Therapeutic procedural characteristics with average relief per procedure, and average total relief in weeks over a period of 2 years.

| Number (70) |

|

|---|---|

| At One Year | |

| Average number of procedures per one year | 3.3 ± 1.07 |

| Total number of procedures in one year | 233 |

| Average total relief per one year (weeks) | 40.7 ± 19.62 |

| At Two Years | |

| Average number of procedures per two years | 5.7 ± 2.73 |

| Total number of procedures in two years | 397 |

| Average total relief per two years (weeks) | 71.1 ± 37.4 |

| Average Relief per Procedure | 13.2 ± 12.6 |

Outcomes

Pain Relief

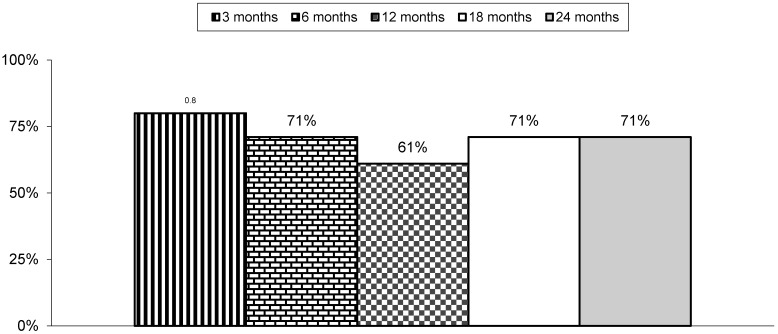

Table 3 and Figure 1 illustrate the proportion of patients with significant pain relief and functional status improvement. The primary outcome measure of 50% improvement with NRS and ODI was seen in 71% of patients at the end of 2 years. There was also a significant difference noted in NRS and ODI scores from baseline to various assessment periods of 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months.

Table 3.

Comparison of Numeric Rating Scale for pain and Oswestry Disability Index score summaries at six time points.

| Time Points | Numeric Pain Rating Score Mean ± SD |

Oswestry Disability Index Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 8.0 ± 0.83 | 31.1 ± 4.10 |

| 3 months | 3.6# ± 1.10 (84%) |

15.3# ± 4.90 (80%) |

| 6 months | 3.8# ± 1.15 (79%) |

15.6# ± 4.62 (71%) |

| 12 months | 4.0# ± 1.27 (69%) |

15.9# ± 5.00 (66%) |

| 18 months | 3.9# ± 1.35 (73%) |

15.5# ± 5.12 (73%) |

| 24 months | 4.2# ± 1.90 (71%) |

15.3# ± 5.36 (73%) |

| Baseline vs follow-up points | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Percentages in parenthesis illustrates proportion with significant pain relief (≥ 50%) from baseline

* indicates significant difference with baseline values (P < 0.05)

Fig 1.

Proportion of patients with significant relief with Numeric Rating Scale and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) of ≥ 50%

Opioid Intake

Opioid intake is described in Table 4. Opioid intake was reduced at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 month follow-up periods compared to baseline.

Table 4.

Opioid intake (morphine equivalence mg).

| Narcotic intake (Morphine Equivalence mg) |

Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | ||

| Baseline | 59 ± 48.4 | |

| 3 months | 41* ± 35.4 | |

| 6 months | 41* ± 35.9 | |

| 12 months | 43* ± 37.4 | |

| 18 months | 42* ± 36.4 | |

| 24 months | 43* ± 37.4 | |

| Baseline vs follow-up points | 0.001 | |

* indicates significant difference with baseline values (p < 0.05)

Characteristics of Weight Monitoring

Characteristics of weight monitoring are described in Table 5. There was no significant change in the overall weight at the end of one year or two years. Twenty-three percent gained weight, 54% lost weight, and 23% remained the same. At the end of 2 years, 27% gained weight, 57% lost weight, and 16% were with no change in their weight.

Table 5.

Characteristics weight monitoring.

| Weight (lbs) | |

|---|---|

| Weight at Beginning | 181.2 ± 48.06 |

| At one year | |

| Weight at one year | 175.7 ± 46.25 |

| Change from baseline | -5.4 ± 13.53 |

| No change | 23% |

| Gained weight | 23% |

| Lost weight | 54% |

| At two years | |

| Weight at two years | 175.7 ± 48.63 |

| Change from baseline | -5.4 ± 17.04 |

| No change | 16% |

| Gained weight | 27% |

| Lost weight | 57% |

Employment Characteristics

There were only 4 patients eligible for employment at baseline. Of these, 2 were employed at baseline. At the end of one year and 2 years, 3 were employed.

Adverse Events

There were no major adverse events reported over a period of 2 years. Subarachnoid puncture was noted on 6 instances with weakness developing in 2 patients with no long-term sequelae or post lumbar puncture headache.

Discussion

This study was a prospective evaluation of the effectiveness of percutaneous adhesiolysis with targeted delivery of injectate in 70 patients suffering from lumbar central stenosis with a 2-year follow-up. The results showed a successful primary outcome measure with a significant reduction of pain and improvement in function in 71% of the patients at the end of 2 years. The results were similar to the previous evaluation of a randomized trial 32 in which 76% of patients in the adhesiolysis group showed over 50% pain relief and functional improvement. The average procedures for 2 years were 5.7 ± 2.73. The average relief over a period of 2 years was 71.1 ± 37.4 weeks over a period of 104 weeks. The results of this observational study illustrate that percutaneous adhesiolysis with targeted delivery of injectate is superior to either caudal or lumbar interlaminar epidural injections in central spinal stenosis, specifically in those who have failed to respond to fluoroscopically directed caudal or lumbar epidural injections 24,25,28,29.

This study may be criticized for the lack of a control group and inclusion of less than 100 patients in an observational study. In conducting this study, however, specifically with the randomized phase, we faced multiple issues with recruitment, continuation in the study without unblinding despite the lack of pain relief and long-term follow-up. Consequently, the consideration of central spinal stenosis after a failure to respond to fluoroscopically directed epidural injections is a difficult management issue. We consider that 70 patients in the observational phase with a 2-year follow-up is appropriate. The number of patients who withdrew or were not available for follow-up at the end of 2 years was less than 30%, which is acceptable based on Cochrane review criteria for randomized trials 64. On the issue of placebo control, the difficulties are insurmountable when utilizing interventional techniques in the United States. These difficulties contributed to our failure to complete the study as expected. Damen et al 65 reviewed the issue of terminating clinical trials due to an insufficient number of subjects. They noted that the research question is unlikely to be answered reliably if the requisite number of subjects is not met, and that the continued participation of the study participants at inadequate levels may expose patients to unnecessary risks and burdens. The results of this study 65 showed that a considerable proportion of studies (41 of 107) were terminated due to failure to recruit a sufficient number of subjects. Furthermore, the authors found that investigator-initiated studies have significantly more problems when recruiting the requisite number of subjects than studies initiated by pharmaceutical companies. This may be due to the remuneration offered in pharmaceutical studies when compared with investigator-initiated studies. Our experience has been to the contrary when recruiting required subjects. Of the 16 studies performed by these investigators, this was the first study for which the required number of patients was not recruited. The major issue has been placebo control groups, for which patients are difficult to recruit. Consequently, active-control groups facilitate easier recruitment and also short-term follow-up will facilitate the recruitment. In addition, Damen et al 65 found that 40% of study results were published with the inclusion of the correct number of subjects, compared with 32% of studies where the requisite number of subjects was not obtained. Nevertheless, protocol violations were reported only twice. Consequently, in this evaluation, all information has been provided so that the study may be assessed appropriately. The study was converted into an observational study as to avoid having to subject patients to enrollment and subsequent withdrawal.

An observational study is defined as an etiologic or effectiveness study 66. Even though in the paradigm of evidence-based medicine (EBM) randomized trials have been considered as the highest quality of evidence, EBM by no means is limited to randomized trials only. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines clinical trials as, “any research study that prospectively assigns human participants or groups of humans to one or more health-related interventions to evaluate the effects on health outcomes 67.” Thus, to improve the effectiveness and safety of patient care, there is a growing emphasis on evidence-based interventional pain management and the incorporation of high quality evidence into clinical practice including observational studies. Furthermore, the majority of studies in interventional pain management are observational and treatments, including surgery, are more likely to be based on observational studies than are those in internal medicine, which are based on randomized controlled trials. The basis for randomized trials arises from the evidence that many surgical and medical interventions recommended that were based on observational studies have later been demonstrated to be ineffective or even harmful 68-72. However, contradictory evidence has been demonstrated for randomized control trials also 49,73. The evidence from observational studies has been shown to be viable in multiple reviews. The poor quality of reporting in observational intervention studies was reported as a potential factor for confounding bias in 98% of studies 74. In a 2005 publication, Hartz et al 75 assessed observational studies of medical treatments and concluded that reporting was often inadequate for use in comparing the study designs or allowing for any other meaningful interpretation of the results. However, the concept that the assignment of subjects randomly to either experimental or control groups is a perfect science also has been questioned. In contrast to Hartz et al's assessment in 2005 75, Benson and Hartz 76 in a 2000 publication comparing observational studies and randomized controlled trials found little evidence that estimates of treatment effects in observational studies reported after 1984, were either consistently larger than or qualitatively different from those obtained in randomized controlled trials. Furthermore, Hartz et al 77, in a 2003 publication assessing observational studies of chemonucleolysis, concluded that the results suggested that a review of several comparable observational studies may help evaluate treatment, identify patient types most likely to benefit from a given treatment, and provide information about study features that can improve the design of subsequent observational studies or even randomized controlled trials. However, they caution that the potential of comparative observational studies has not been realized because of concurrent inadequacies in their design, analysis, and reporting. Concato et al 78 in a 2000 publication evaluating published articles in 5 major medical journals from 1991 to 1995, concluded that the results of well-designed observational studies do not systematically overestimate the magnitude of the effects of treatment as compared with those of randomized controlled trials on the same topic. In fact, Shrier et al 79 in 2007, found that the advantages of including both observational studies and randomized trials in a meta-analysis could outweigh the disadvantages in many situations and that observational studies should not be excluded a priori. In addition, an assessment of the methodological quality of observational studies has been described extensively 24-27,49,80. Thus, observational studies are important in assessing the effectiveness of interventions.

The mechanism of neural blockade has been described to be complex with alternation or interruption of nociceptive input, the reflex mechanism of afferent fibers, self-sustaining activity of the neurons, and the pattern of central neuronal activities 81. Among the multiple drugs utilized in this procedure, corticosteroids have been shown to reduce inflammation by inhibiting the synthesis of a number of pro-inflammatory mediators 82-84. Local anesthetics also have shown to provide short to long-term symptomatic relief based on various mechanisms including suppression of nociceptive discharge, blockade of the sympathetic reflex arch, block of axonal transport of nerve fibers, and anti-inflammatory effects 85-90. In addition, local anesthetics and steroids also provided similar relief when they were injected individually in experimental settings 91,92 and also in multiple clinical settings 26,28,29,32,43,54-63,81. Finally, hypertonic sodium chloride solution has been shown to provide neurolysis and analgesia by various mechanisms 43,46. While the results in this study are shown to improve patients after they have failed conservative modalities including fluoroscopically directed epidural injections, the role of percutaneous adhesiolysis in foraminal stenosis without central spinal stenosis is not known. The results of this evaluation are only limited to central spinal stenosis without surgical interventions. It is interesting to evaluate the role of each component of percutaneous adhesiolysis in reference to adhesiolysis, injection of local anesthetic, injection of steroids, and injection of hypertonic sodium chloride solution.

Overall, the results of this observational study of 70 patients with a long-term follow-up of 2 years show that percutaneous adhesiolysis may be an effective modality in patients failing to respond to fluoroscopically directed epidural injections and also other conservative modalities of treatment.

Conclusion

This observational study showed that 71% of 70 patients met the primary outcome measure with an improvement in physical and functional status of at least 50%. Consequently, the results of this study show that percutaneous adhesiolysis in central spinal stenosis without surgical intervention after failure of conservative modalities including fluoroscopically directed epidural injections may be an effective modality.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Sekar Edem for assistance in the search of the literature, Alvaro F. Gómez, MA for manuscript review, and Tonie M. Hatton and Diane E. Neihoff, transcriptionists, for their assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Haig AJ, Tomkins CC. Diagnosis and management of lumbar spinal stenosis. JAMA. 2010;303:71–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalichman L, Cole R, Kim DH. et al. Spinal stenosis prevalence and association with symptoms: The Framingham Study. Spine J. 2009;9:545–50. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boden SD, McCowin PR, Davis DO, Dina TS, Mark AS, Wiesel S. Abnormal magnetic resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects: A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:403–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovacs FM, Urrútia G, Alarcón JD. Surgery versus conservative treatment for symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:E1335–51. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820c97b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi S, Baba H, Uchida K. et al. Blood circulation of cauda equina and nerve root [in Japanese] Clin Calcium. 2005;15:63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter RW. Spinal stenosis and neurogenic claudication. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:2046–52. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199609010-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, Kagechika K, Takino T, Matsui T, Miyazaki T, Shima I. Changes in epidural pressure during walking in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:2746–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199512150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi K, Miyazaki T, Takino T, Matsui T, Tomita K. Epidural pressure measurements. Relationship between epidural pressure and posture in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:650–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi S, Kokubo Y, Uchida K. et al. Effect of lumbar nerve root compression on primary sensory neurons and their central branches: changes in the nociceptive neuropeptides substance P and somatostatin. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:276–82. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000152377.72468.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall S, Bartleson JD, Onofrio BM, Baker HL Jr, Okazaki H, O'Duffy JD. Lumbar spinal stenosis: clinical features, diagnostic procedures, and results of surgical treatment in 68 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:271–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-2-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedly JL, Bresnahan BW, Comstock B. et al. Study protocol- Lumbar Epidural steroid injections for Spinal Stenosis (LESS): A double-blind randomized controlled trial of epidural steroid injections for lumbar spinal stenosis among older adults. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Graaf I, Prak A, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Thomas S, Peul W, Koes B. Diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis. A systematic review of the accuracy of diagnostic tests. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:1168–76. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000216463.32136.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steurer J, Roner S, Gnannt R, Hodler J; LumbSten Research Collaboration. Quantitative radiologic criteria for the diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis: A systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:175. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deyo RA, Ciol MA, Cherkin DC, Loeser JD, Bigos SJ. Lumbar spinal fusion: A cohort study of complications, reoperations, and resource use in the Medicare population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993;18:1463–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deyo RA, Gray DT, Kreuter W, Mirza S, Martin BI. United States trends in lumbar fusion surgery for degenerative conditions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1441–5. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166503.37969.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ammendolia C, Stuber K, de Bruin LK. et al. Nonoperative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis with neurogenic claudication: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:E609–16. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318240d57d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI, Kreuter W, Goodman DC, Jarvik JG. Trends, major medical complications, and charges associated with surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303:1259–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson AN, Blood E, Hanscom B, Herkowitz H, Cammisa F, Albert T, Boden SD, Hilibrand A, Goldberg H, Berven S, An H; SPORT Investigators. Surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:794–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen E, Tong KB, Laouri M. Surgical treatment patterns among Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine J. 2010;10:588–94. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummins J, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD. et al. Descriptive epidemiology and prior healthcare utilization of patients in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial's (SPORT) three observational cohorts: Disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:806–14. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000207473.09030.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malmivaara A, Slätis P, Heliövaara M, et al; Finnish Lumbar Spinal Research Group. Surgical or nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis? A randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000251014.81875.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tosteson AN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al; SPORT Investigators. Surgical treatment of spinal stenosis with and without degenerative spondylolisthesis: Cost-effectiveness after 2 years. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:845–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-12-200812160-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benyamin RM, Manchikanti L, Parr AT. et al. The effectiveness of lumbar interlaminar epidural injections in managing chronic low back and lower extremity pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15:E363–E404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parr AT, Manchikanti L, Hameed H. et al. Caudal epidural injections in the management of chronic low back pain: A systematic appraisal of the literature. Pain Physician. 2012;15:E159–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manchikanti L, Buenaventura RM, Manchikanti KN. et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic lumbar transforaminal epidural steroid injections in managing lumbar spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15:E199–E245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helm S II, Benyamin RM, Chopra P, Deer TR, Justiz R. Percutaneous adhesiolysis in the management of chronic low back pain in post lumbar surgery syndrome and spinal stenosis: A systematic review. Pain Physician. 2012;15:E435–E462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manchikanti L, Cash RA, McManus CD, Pampati V, Fellows B. Fluoroscopic caudal epidural injections with or without steroids in managing pain of lumbar spinal stenosis: One year results of randomized, double-blind, active-controlled trial. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2012;25:226–34. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3182160068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manchikanti L, Cash KA, McManus CD, Damron KS, Pampati V, Falco FJE. Lumbar interlaminar epidural injections in central spinal stenosis: Preliminary results of a randomized, double-blind, active control trial. Pain Physician. 2012;15:51–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park CH, Lee SH, Jung JY. Dural sac cross-sectional area does not correlate with efficacy of percutaneous adhesiolysis in single level lumbar spinal stenosis. Pain Physician. 2011;14:377–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briggs VG, Li W, Kaplan MS, Eskander MS, Franklin PD. Injection treatment and back pain associated with degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis in older adults. Pain Physician. 2010;13:E347–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manchikanti L, Cash KA, McManus CD, Pampati V, Singh V, Benyamin RM. The preliminary results of a comparative effectiveness evaluation of adhesiolysis and caudal epidural injections in managing chronic low back pain secondary to spinal stenosis: A randomized, equivalence controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2009;12:E341–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Pampati V, Smith HS, Hirsch JA. Analysis of growth of interventional techniques in managing chronic pain in Medicare population: A 10-year evaluation from 1997 to 2006. Pain Physician. 2009;12:9–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staal JB, de Bie R, de Vet HC, Hildebrandt J, Nelemans P. Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD001824. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001824.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou R, Huffman L. Evaluation and Management of Low Back Pain: Evidence Review. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manchikanti L, Datta S, Gupta S. et al. A critical review of the American Pain Society clinical practice guidelines for interventional techniques: Part 2. Therapeutic interventions. Pain Physician. 2010;13:E215–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V. et al. Comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in the management of chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2009;12:699–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Specialty Utilization data files from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/

- 39.Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Singh V, Boswell MV, Smith HS, Hirsch JA. Explosive growth of facet joint interventions in the Medicare population in the United States: A comparative evaluation of 1997, 2002, and 2006 data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:84. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Falco FJE, Hirsch JA. Growth of spinal interventional pain management techniques: Analysis of utilization trends and medicare expenditures 2000 to 2008. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Abbott ZI, Nair KV, Allen RR, Akuthota VR. Utilization characteristics of spinal interventions. Spine J. 2012;1:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manchikanti L, Helm II S, Fellows B. et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15:ES9–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manchikanti L, Rivera JJ, Pampati V. et al. One day lumbar epidural adhesiolysis and hypertonic saline neurolysis in treatment of chronic low back pain: A randomized, double-blind trial. Pain Physician. 2004;7:177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerdesmeyer L, Lampe R, Veihelmann A. et al. Chronic radiculopathy. Use of minimally invasive percutaneous epidural neurolysis according to Racz. Schmerz. 2005;19:285–295. doi: 10.1007/s00482-004-0371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Veihelmann A, Devens C, Trouillier H, Birkenmaier C, Gerdesmeyer L, Refior HJ. Epidural neuroplasty versus physiotherapy to relieve pain in patients with sciatica: A prospective randomized blinded clinical trial. J Orthop Sci. 2006;11:365–9. doi: 10.1007/s00776-006-1032-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heavner JE, Racz GB, Raj P. Percutaneous epidural neuroplasty: Prospective evaluation of 0.9% NaCl versus 10% NaCl with or without hyaluronidase. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1999;24:202–7. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(99)90128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, et al; CONSORT GROUP (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:663–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fairbank JCT, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry disability index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2940–53. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Smith HS. Evidence-based medicine, systematic reviews, and guidelines in interventional pain management: Part 2: Randomized controlled trials. Pain Physician. 2008;11:717–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pereira J, Lawlor P, Vigano A, Dorgan M, Bruera E. Equianalgesic dose ratios for opioids. A critical review and proposals for long-term dosing. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:672–87. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carragee EJ. The rise and fall of the “minimum clinically important difference”. Spine J. 2010;10:283–4. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carragee EJ, Chen I. Minimum acceptable outcomes after lumbar spinal fusion. Spine J. 2010;10:313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG. Testing minimal clinically important difference: consensus or conundrum? Spine J. 2010;10:321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Cash KA. Protocol for evaluation of the comparative effectiveness of percutaneous adhesiolysis and caudal epidural steroid injections in low back and/or lower extremity pain without post surgery syndrome or spinal stenosis. Pain Physician. 2010;13:E91–E110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Cash KA, Pampati V. Evaluation of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks in managing chronic low back pain: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial with a 2-year follow-up. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:124–35. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Cash KA, Fellows B. Comparative outcomes of a 2-year follow-up of cervical medial branch blocks in management of chronic neck pain: A randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2010;13:437–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Cash KA, Pampati V, Fellows B. Comparative effectiveness of a one-year follow-up of thoracic medial branch blocks in management of chronic thoracic pain: A randomized, double-blind active controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2010;13:535–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Cash KA, Pampati V, Damron KS, Boswell MV. A randomized, controlled, double-blind trial of fluoroscopic caudal epidural injections in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation and radiculitis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:1897–1905. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31823294f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manchikanti L, Cash KA, McManus CD, Pampati V, Smith HS. One year results of a randomized, double-blind, active controlled trial of fluoroscopic caudal epidural injections with or without steroids in managing chronic discogenic low back pain without disc herniation or radiculitis. Pain Physician. 2011;14:25–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Cash KA, Pampati V, Datta S. Management of pain of post lumbar surgery syndrome: One-year results of a randomized, double double-blind, active controlled trial of fluoroscopic caudal epidural injections. Pain Physician. 2010;13:509–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, Cash KA, Pampati V. Evaluation of the effectiveness of lumbar interlaminar epidural injections in managing chronic pain of lumbar disc herniation or radiculitis: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2010;13:343–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Manchikanti L, Cash KA, Pampati V, Wargo BW, Malla Y. The effectiveness of fluoroscopic cervical interlaminar epidural injections in managing chronic cervical disc herniation and radiculitis: Preliminary results of a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2010;13:223–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manchikanti L, Cash KA, McManus CD, Pampati V, Benyamin RM. A preliminary report of a randomized double-blind, active controlled trial of fluoroscopic thoracic interlaminar epidural injections in managing chronic thoracic pain. Pain Physician. 2010;13:E357–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M; Editorial Board, Cochrane Back Review Group. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:1929–41. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1c99f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Damen L, van Agt F, de Boo T, Huysmans F. Terminating clinical trials without sufficient subjects. J Med Ethics. 2012;38:413–6. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Smith HS, Hirsch JA. Evidence-based medicine, systematic reviews, and guidelines in interventional pain management: Part 4: Observational studies. Pain Physician. 2009;12:73–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), 2007. World Health Organization; www.who.int/entity/ictrp/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 68.Antman K, Ayash L, Elias A. et al. A phase II study of high-dose cyclophosphamide, thiotepa, and carboplatin with autologous marrow support in women with measurable advanced breast cancer responding to standard-dose therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:102–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Farquhar C, Marjoribanks J, Basser R, Hetrick S, Lethaby A. High dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow or stem cell transplantation versus conventional chemotherapy for women with metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005. CD003142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Peters WP, Shpall EJ, Jones RB. et al. High-dose combination alkylating agents with bone marrow support as initial treatment for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:1368–1376. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.9.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.The EC/IC Bypass Study Group. Failure of extracranial-intracranial arterial bypass to reduce the risk of ischemic stroke. Results of an international randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1191–1200. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511073131904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weinstein PR, Rodriguez Y, Baena R, Chater NL. Results of extracranial-intracranial arterial bypass for intracranial internal carotid artery stenosis: Review of 105 cases. Neurosurgery. 1984;15:787–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guyatt G, Drummond R. Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence- Based Clinical Practice. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2002. Part 2. The Basics: Using and Teaching the Principles of Evidence-Based Medicine. 2B1. Therapy and validity; pp. 247–308. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Groenwold RH, Van Deursen AM, Hoes AW, Hak E. Poor quality of reporting confounding bias in observational intervention studies: A systematic review. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:746–751. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hartz A, Bentler S, Charlton M. et al. Assessing observational studies of medical treatments. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2005;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Benson K, Hartz AJ. A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1878–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hartz A, Benson K, Glaser J, Bentler S, Bhandari M. Assessing observational studies of spinal fusion and chemonucleolysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:2268–75. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000085093.68773.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1887–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shrier I, Boivin JF, Steele RJ. et al. Should meta-analyses of interventions include observational studies in addition to randomized controlled trials? A critical examination of underlying principles. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1203–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.West S, King V, Carey TS, Systems to Rate the Strength of Scientific Evidence, Evidence Report, Technology Assessment No.47; AHRQ Publication No.02-E016. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2002. www.thecre.com/pdf/ahrq-system-strength.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Manchikanti L. Role of neuraxial steroids in interventional pain management. Pain Physician. 2002;5:182–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Byrod G, Otani K, Brisby H. et al. Methylprednisolone reduces the early vascular permeability increase in spinal nerve roots induced by epidural nucleus pulposus application. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:983–7. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hayashi N, Weinstein JN, Meller ST. et al. The effect of epidural injection of betamethasone or bupivacaine in a rat model of lumbar radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:877–85. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199804150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee HM, Weinstein JN, Meller ST. et al. The role of steroids and their effects on phospholipase A2: an animal model of radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:1191–96. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199806010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pasqualucci A, Varrassi G, Braschi A. et al. Epidural local anesthetic plus corticosteroid for the treatment of cervical brachial radicular pain: single injection versus continuous infusion. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:551–7. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318074c95c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ji RR, Woolf CJ. Neuronal plasticity and signal transduction in nociceptive neurons: Implications for the initiation and maintenance of pathological pain. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:1–10. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pasqualucci A. Experimental and clinical studies about the preemptive analgesia with local anesthetics. Possible reasons of the failure. Minerva Anestesiol. 1998;64:445–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arner S, Lindblom U, Meyerson BA. et al. Prolonged relief of neuralgia after regional anesthetic block. A call for further experimental and systematic clinical studies. Pain. 1990;43:287–97. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90026-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lavoie PA, Khazen T, Filion PR. Mechanisms of the inhibition of fast axonal transport by local anesthetics. Neuropharmacology. 1989;28:175–81. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(89)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cassuto J, Sinclair R, Bonderovic M. Anti-inflammatory properties of local anesthetics and their present and potential clinical implications. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:265–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sato C, Sakai A, Ikeda Y. et al. The prolonged analgesic effect of epidural ropivacaine in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:313–20. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000296460.91012.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tachihara H, Sekiguchi M, Kikuchi S. et al. Do corticosteroids produce additional benefit in nerve root infiltration for lumbar disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:743–7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181696132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]