Abstract

We tested if small conductance, Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels (SKCa) precondition hearts against ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury by improving mitochondrial (m) bioenergetics, if O2–derived free radicals are required to initiate protection via SKCa channels, and, importantly, if SKCa channels are present in cardiac cell inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM). NADH and FAD, superoxide (O2•−), and m[Ca2+] were measured in guinea pig isolated hearts by fluorescence spectrophotometry. SKCa and IKCa channel opener DCEBIO (DCEB) was given for 10 min ending 20 min before IR. Either TBAP, a dismutator of O2•−, NS8593, an antagonist of SKCa isoforms, or other KCa and KATP channel antagonists, was given before DCEB and before ischemia. DCEB treatment resulted in a 2-fold increase in LV pressure on reperfusion and a 2.5 fold decrease in infarct size vs. non-treated hearts associated with reduced O2•− and m[Ca2+], and more normalized NADH and FAD during IR. Only NS8593 and TBAP antagonized protection by DCEB. Localization of SKCa channels to mitochondria and IMM was evidenced by a) identification of purified mSKCa protein by Western blotting, immuno-histochemical staining, confocal microscopy, and immuno-gold electron microscopy, b) 2-D gel electrophoresis and mass spectroscopy of IMM protein, c) [Ca2+]–dependence of mSKCa channels in planar lipid bilayers, and d) matrix K+ influx induced by DCEB and blocked by SKCa antagonist UCL1684. This study shows that 1) SKCa channels are located and functional in IMM, 2) mSKCa channel opening by DCEB leads to protection that is O2•− dependent, and 3) protection by DCEB is evident beginning during ischemia.

Keywords: cardiac mitochondria, inner mitochondrial membrane, cell signaling, ischemia reperfusion injury, oxidant stress, small conductance Ca2+ -sensitive K+ channel

1. Introduction

Depressed mitochondrial (m) bioenergetics, excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and mCa2+ loading are major factors underlying ischemia and reperfusion (IR) injury [1]. Prophylactic measures targeted in part to mitochondria that reduce cardiac IR injury [2, 3] include ischemic preconditioning (IPC, i.e., brief pulses of ischemia and reperfusion before longer ischemia) and pharmacologic pre-conditioning (PPC), i.e., cardiac protection elicited some time after the drug is washed out. PPC is theoretically a better approach because it does not require the heart to first undergo brief ischemia. We reported previously that activation of a large (big) conductance Ca2+ –sensitive K+ channel (mBKCa), which may be located in the cardiac myocyte inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), can induce PPC [4]. The BKCa channel has not been found in the cardiac myocyte plasma membrane, but we have shown that a BKCa channel opener, NS1619, has biphasic effects on mitochondrial respiration, membrane potential (ΔΨm), and superoxide radical (O2•−) production in isolated mitochondria [5, 6]. This suggested that opening of other mitochondrial K+ channels could also elicit PPC.

There are other KCa channels of intermediate or small conductances identified in non-cardiac cells [7–10] that are membrane bound, calmodulin (CaM) –dependent and gated by Ca2+ and other factors. These channels have smaller unit conductances of 3–30 (small, SKCa) and 20–90 (intermediate IKCa) pS [11]. The opening of SKCa channels is initiated by Ca2+ binding to calmodulin at the C terminus of the channel [12, 13]. Of the known isoforms of SKCa channels that have been identified in endothelial cells, one is KCa2.3, which was found to exert a potent, tonic hyperpolarization that reduced vascular smooth muscle tone [14]. Moreover, there is evidence for the KCa2.2 isoform in rat and human hearts using Western blot analysis and reverse transcription -polymerase chain reaction [15]. Clones of the channel from atria and ventricles showed much greater expression in atria compared to ventricles, and electrophysiological recordings exhibited much greater atrial than ventricular sensitivity to AP repolarization by apamin, a selective SKCa antagonist [15, 16].

We postulated that activation of SKCa channels induces a preconditioning effect similar to that elicited by a BKCa (KCa1.1, maxi-K) opener, and that this effect is mediated via channels located in the IMM, i.e., they promote K+ entry into the mitochondrial matrix. We tested if the KCa3.1 (IKCa1) [7, 9, 17] and KCa2.2 and KCa2.3 (SKCa) [18–21] opener DCEBIO (DCEB), given transiently before ischemia, elicits PPC in a manner similar to that of the mBKCa channel opener NS1619 [4]. We specifically examined the role of DCEB in attenuating the deleterious effects of IR injury on mitochondrial bioenergetics by near continuous measurement of m[Ca2+], NADH and FAD, and O2•− in isolated perfused hearts. We infused NS8593 to antagonize SKCa channel opening [22, 23], and several other K+ channel blockers to rule out effects of DCEB on other putative mK+ channels, i.e., IKCa (KCa3.1) BKCa, and KATP channels. Because protective effects of putative KATP [24] and BKCa [4] channel openers can be abolished by ROS scavengers, we similarly bracketed DCEB with a matrix targeted dismutator of O2•− to assess the role of SKCa channel opening on O2•− production, presumably by mitochondrial respiratory complexes. We used several approaches to furnish solid evidence for the presence and functionality of SKCa channel proteins in the IMM of guinea pig isolated cardiac mitochondria, and in isolated IMM.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Isolated heart model

The investigation conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication 85-23, revised 1996). Guinea pig hearts were isolated and prepared as described in detail [4, 25–31] with care to minimize IPC. These were pre-oxygenation, maintained respiration after anesthesia with ketamine (50 mg/kg), and immediate aortic perfusion with cold perfusate. Hearts were instrumented with a saline filled balloon and transducer to measure left ventricular pressure (LVP) and an aortic flow probe to measure coronary flow (CF). Heart rate and rhythm were measured via atrial and ventricular electrodes. Hearts were perfused at constant pressure with modified Krebs-Ringer’s solution at 37°C. Heart rate (HR) and rhythm, myocardial function (isovolumetric LVP), coronary flow and venous pO2 were measured continuously. %O2 extraction, myocardial O2 consumption (MVO2) and cardiac efficiency (HR•LVP/MVO2) were calculated. At 120 min reperfusion, hearts not isolated for mitochondria were stained with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) and infarct size was determined as a percentage of ventricular heart weight [4, 26, 30].

2.2. Cardiac fluorescence measurements

Either m[Ca2+], NADH and FAD, or ROS (principally O2•−) was measured near continuously or intermittently in the heart using one of four excitation (λex) and emission (λem) fluorescence spectra described below. NADH and FAD were measured in the same heart; m[Ca2+] and ROS were measured in different subsets of hearts. A trifurcated fiberoptic probe (3.8 mm2 per bundle) was placed against the LV to excite and to record light signals at specific λ’s using spectrophotofluorometers (SLM Amico-Bowman and Photon Technology International). The incident polychromic light was filtered at 350 or 490 nm and recorded at 390/450 or 540 nm, respectively, to measure NADH [25, 28, 30, 32, 33] and FAD [30, 32] tissue autofluorescence. Alternatively, hearts assigned to measure Ca2+, were loaded with 6 µM indo 1 AM for 30 min followed by washout of residual dye for 20 min. Ca2+ transients were recorded at the same wavelengths as for NADH. Then hearts were perfused with MnCl2 to quench cytosolic Ca2+ to reveal non-cytosolic [Ca2+], mostly [mCa2+] [25, 29, 33]. In other hearts, as reported earlier [4, 26, 27, 31, 33, 34], dihydroethidium (10 µM, DHE), which is used to measure intracellular superoxide (O2•−) level, was loaded for 30 min and washed out of residual dye for 20 min. The LV wall was excited with light λex 540 nm; λem 590 nm) to measure a fluorescence signal that is primarily a marker of the free radical O2•−.[31, 35] DHE enters cells and is oxidized by O2•− where it is converted to the labile cation, 2-hydroxyethidium (2-HE+), which causes a red-shift in the EM light spectrum [36, 37].

Myocardial fluorescence intensity was recorded in arbitrary fluorescence units (afu) during 35 discrete sampling periods throughout each experiment at a sampling rate of 100 points/s (100 Hz, pulse width 1 µs) during a 12 s triggered period for O2•− and for a 2.5 s triggered period for NADH and FAD, and m[Ca2+]. For each fluorescence study, no drug alone had any effect on background autofluorescence. Signals were digitized and recorded at 200 Hz (Power LAB/16sp, Chart and Scope version 3.6.3. AD Instruments) on G5 Macintosh computers for later analysis using specifically designed programs with MATLAB (MathWorks) and Microsoft Excel software. All variables were averaged over the 2.5 or 12 s sampling period.

2.3. Protocol

Hearts were infused with 3 µM DCEBIO (DCEB) for 10 min ending 20 min before the onset of 30 min global ischemia. DCEB is derived from the benzimidazolone class of compounds, which are known to stimulate chloride secretion in epithelial cells [7, 8, 38]. DCEB non-selectively opens KCa2.2 and 2.3 channels [7, 18–21]. In most hearts DCEB was bracketed either with 40 µM PAX (paxilline), a blocker of BKCa channels [39], 20 µM TBAP, a chemical dismutator of O2•− that can enter the matrix, 200 µM GLIB (glibenclamide), a KATP channel blocker, or 100 nM TRAM (TRAM-34), an established blocker of IKCa conductance channels [9]. TRAM was selected because DCEB also opens IKCa channels [7, 9, 17, 21]. PAX, TBAP, GLIB, or TRAM was given 5 min before, during DCEB perfusion, and for 5 min after stopping DCEB. In a separate study DCEB was bracketed with 10 µM NS8593, a specific antagonist of SKCa channels [22, 23] to compare with a no drug IR control. Drug exposure was discontinued 15 min before the onset of global ischemia. lasted 120 min. NS8593 caused a transient fall in systolic (and developed) LVP and an increase in coronary flow. Additional studies (not displayed) showed that each of these drugs, except for NS8593, given alone (without DCEB) for 20 min before ischemia elicited no appreciable effects and had no different effect on IR injury than the drug-free controls.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

A total of 155 isolated heart experiments were divided into 7 groups, a drug-free control, and DCEB alone or plus NS8593, PAX, TBAP, GLIB or TRAM. Functional data were recorded from 12–15 hearts per group. Infarct size was measured in a blinded manner in 8 hearts per group. NADH and FAD were measured in approximately 6–8 hearts per group, O2•− in 5–7 hearts per group, and m[Ca2+] in 6–8 hearts per group. Because functional studies showed trends that PAX, GLIB, or TRAM did not block protective effects of DCEB, only four groups were compared in NADH and FAD experiments and three groups were compared in O2•− and m[Ca2+] experiments. All data were expressed as means ± standard error of means. Appropriate comparisons were made among groups that differed by a variable at a given condition or time, and within a group over time compared to the initial control data. Statistical differences were measured across groups at specific time points (20, 50, 85, 145, and 200 min). Differences among variables were determined by two-way multiple ANOVA for repeated measures (Statview® and CLR anova® software programs for Macintosh®); if F tests were significant, appropriate post-hoc tests (e.g., Student-Newman-Keul’s, SNK) were used to compare means. The incidence of ventricular fibrillation (VF) vs. sinus rhythm per group, and the number of VF’s per heart per group, were determined by Fisher’s Exact Test. In mitochondria K+ flux experiments drug treatments were compared to control using the same statistical tests. Mean values were considered significant at P values (two-tailed) <0.05.

2.5. Isolation of cardiac mitochondria and inner mitochondrial membranes (IMMs)

Mitochondria were freshly isolated from 25 guinea pig hearts by differential centrifugation as described previously [5, 6, 34, 40, 41]. To test mitochondrial viability and function in each preparation, the respiratory control index (RCI, state 3/state 4) was determined under both pyruvate (P, 10 mM), and succinate (S, 10 mM) + rotenone (R, 4 µM) conditions. State 3 respiration was determined after adding 250 µM ADP. Intact mitochondrial preparations were discarded if the RCI was less than 3 with succinate + R or less than 9 with pyruvate.

To isolate fraction-enriched IMMs, isolated mitochondria were shocked osmotically by incubating in 10 mM phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) for 20 min, and then in 20% sucrose for another 15 min. The IMMs were sonicated for 30 s, 3 times, and then centrifuged at 8,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant containing sub-mitochondrial particles was fractionated using a continuous sucrose gradient (30% to 60%) and centrifuged at 80,000 g overnight in a SW28 rotor. The IMMs (enriched in the heavy fractions) were suspended with the isolation medium without EGTA and centrifuged at 184,000 g for 30 min. The final pellet enriched IMMs were suspended in isolation medium without EGTA and BSA and stored at −80°C in small aliquots until use.

2.6. Enhancement of calmodulin-binding proteins from IMM

Calmodulin binds to SKCa channels so the calmodulin binding proteins obtained from the IMMs were concentrated to enhance the sensitivity of detection of mSKCa channels by Western blotting and by mass spectrometry. For calmodulin column chromatography (calmodulin-sepharose beads) the IMMs (5 mg protein) were solubilized for 2 h at 4°C in washing buffer, 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 200 µM CaCl2, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and 0.5% CHAPS with protease inhibitors. After centrifugation at 50,000 g for 30 min, the supernatant was applied to a calmodulin-sepharose column (10 by 1.5 cm) pre-equilibrated with the solubilization buffer containing 0.1% CHAPS. The column was washed rapidly with 500 mL of washing buffer as above. The proteins were eluted from the column by 2 mM EGTA in the elution buffer (200 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS) after washing. The fractions collected were concentrated and the proteins were separated by 2-D gel electrophoresis as follows.

2.7. Purification of SKCa channel proteins from IMM by isoelectric focusing

After isolating the IMM protein fraction (2.5, 2.6) the first dimension of isoelectric focusing (IEF) during 2-D gel electrophoresis was done in native gel buffer on an Immobilon Drystrips (Amersham) with pH 4~7 gradient. The antibody was targeted to KCa2.3 (aka, hSK3, KCN3, Osenses Pty, Ltd.). The second dimension was done in a 10% Criterion® tris-SDS gel (Bio-Rad). Two identical gels were run at the same time, with one used for transfer to nitrocellulose membrane for Western blot analysis, and the other for silver staining for visualization.

2.8. IMM protein identification using electrospray LC/MS

IMM proteins (from 2.5, 2.6) were digested with trypsin and subjected to pH focusing into 10 fractions over pH 3–10 and each fraction was directly analyzed using a NP LC/ESI mass spectrometer (Finnigan™ LTQ™ Ion Trap MS, Thermo Electron Corporation) to generate specific mass spectra typical for a given protein. The instrument utilizes stepped normalized collision energy (SNCE) to improve fragmentation efficiency over a wide mass range. This increases the capacity of a linear trap and the accuracy and sensitivity of peptide detection in the fmol range. A mass database (NCBI Entrez Pubmed protein) was searched for matching proteins and consequently the SKCa channel protein of interest was tentatively identified in IMM.

2.9. Purification of intact mitochondria by Percoll gradient fractionation

To further verify localization of SKCa channel protein in an intact mitochondria preparation, the Percoll gradient technique [42, 43], with slight modifications, was used to purify intact mitochondria and immuno-histochemical staining was utilized to identify SKCa channel protein. In brief, mitochondria isolated as previously described [5, 6, 34, 40, 41] were layered over 30% Percoll (in buffer A containing 450 mM mannitol, 50 mM HEPES, 2 mM EDTA, pH adjusted to 7.4 followed by addition of 50 mg BSA), and centrifuged at 95,000 g for 30 min. The lower dense band observed at the bottom of the tube, enriched in mitochondria, was collected using a long tip glass pipette. Collected mitochondria (~4 ml) were resuspended in the same buffer used to dilute Percoll, and centrifuged again at 6300 g. The resulting pellet was suspended in the same buffer without BSA (buffer B) and re-centrifuged at 6300 g. The mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in a small volume (~0.3 ml) of buffer B and stored until further use.

2.10. Identification and localization of SKCa channel protein in purified mitochondria

Immuno-histochemical staining with an anti-SKCa antibody and confocal microscopy were used, in part, to verify that SKCa channel protein resides in mitochondria. Briefly, mitochondria, isolated and purified as described above (2.9), were fixed onto poly-lysine coated coverslips. Mitochondrial structures were then fixed using paraformaldehyde and membranes were permeabilized using Triton X-100 and non-specific binding sites blocked by goat serum albumin. Coverslips were then incubated in solution containing anti-KCa2.2 (anti-SK2, ETQMENYDKHVTYNAERS, Alomone Labs (1:1000 in 5% milk)) and anti-ANT (adenine nucleotide translocase, Invitrogen) antibodies for 30 min followed by three washes in 0.1 M PBS. Coverslips were then incubated in appropriate secondary antibodies (Alexa Flour 455 and 546 respectively, Invitrogen (1:3000 in 2% milk)) for another 30 min and were then transferred onto microscope slides and visualized using a Leica confocal microscope (TCS SP5). Alternatively, mitochondria were utilized for immuno-gold labeling to localize SKCa channel protein in individual mitochondria.

2.11. Localization of SKCa channel protein by immuno-gold labeling and electron microscopy

Immuno-electron microscopy (IEM) was used to localize SKCa protein in purified cardiac mitochondria similar to the technique used by Douglas et al. [44] to localize BKCa channel protein in mitochondria. The final mitochondrial pellet, prepared as described above (2.9), was resuspended in 500 µL isolation buffer before centrifugation at 16,000 g for 20 min. The supernatant was discarded and an EM fixative containing 0.1% glutaraldehyde + 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M NaH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.4) was added. After 1h fixation at room temperature the pellet was gently detached from the tube with a 25G needle and processed following the protocols of Berryman and Rodewald [45] and Burleigh et al. [45]. Pellets were washed 3 × 20 min in 0.1M NaH2PO4 buffer containing 3.5% sucrose and 0.5 mM CaCl2, then rinsed in 0.1 M glycine in NaH2PO4 buffer for 1 h on ice before returning to NaH2PO4 buffer. The pellets were cut into 1 mm cubes and then washed 4 × 15 min in 0.1M tris maleate buffer + 3.5% sucrose, pH 6.5, at 4°C followed by post fixation in 2% Uanyl acetate (w/v) in tris buffer, pH 6, for 2 h at 4°C; specimens were then given a final rinse 2 × 5 min in Tris maleate buffer, pH 6.5. The specimens were then processed by the progressive lowering-of-temperature method into Lowicryl K4M resin and the resin was polymerized by UV irradiation. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were cut onto Formvar/carbon coated grids. Immuno-labeling was performed by floating grids on droplets of 0.1 M NaH2PO4 buffer containing 5% BSA (PB-BSA), then incubating with rabbit polyclonal anti-KCa2.2 (anti-SK2, Alomone Labs) diluted 1:50 for 90 min, or with the positive control mitochondrial marker, cytochrome c oxidase (anti-COX1: Complex IV, subunit 1) mouse monoclonal antibody diluted 1:500. Non-immune rabbit polyclonal serum was used as the negative control. This step was followed by 3 × 5 min washes in PB-BSA. The sections were then incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG, or goat anti-mouse IgG, conjugated to 10 nM colloidal gold [46] for 90 min at room temp, rinsed in distilled water, and then stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate. Sections were examined in a JEOL JEM2100 TEM at 80 kV.

2.12. Purification/identification of SKCa channel protein by isoelectric focusing (IEF) and Western blotting

Total mitochondrial protein, once isolated and purified as above (2.9), was partitioned by IEF and the resulting fractions analyzed for mSKCa protein. Mitochondria (1 mg) were suspended in 3 mL electrophoresis buffer (0.1% w/v CHAPS, 0.1% w/v dodecyl maltoside, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mg dithiothreitol) and IEF was performed using the Micro-Rotofor system (BioRad, CA) for 4 h at 400 mA constant current. The fractions thus obtained were collected and analyzed for SKCa protein by Western blot using the anti-KCa2.2 (anti-SK2) antibody. Briefly, equal volumes of the 10 fractions obtained by IEF were suspended in Laemmli buffer and resolved using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) [47], as originally described by Laemmli [48], and transferred onto poly vinilidine difluoride membranes using Transblot System (Bio-Rad) in 50 mM tricine and 7.5 mM imidazole transfer buffer. Membranes were blocked with 10% non fat dry milk in tris buffered saline-TBSt (25 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl and 0.1% Tween 20) by incubating for 1 h followed by incubation in the anti-KCa2.2 antibody (anti-SK2) solution overnight at 4°C. After three washes with TBSt the membrane was incubated with an appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 3 h. After five washes with TBSt the membrane was incubated in enhanced chemiluminescence detection solution (ECL-Plus, GE-Amersham) and exposed to X-ray film for autoradiography. The protein fraction containing the largest amount of SKCa was used for single channel recordings.

2.13. Enriching and incorporating mSKCa channel protein into lipid bilayers

Channel activity of the purified and enriched mSKCa protein was monitored by incorporating it into a planar lipid bilayer, as previously described [49]. Briefly, phospholipids were prepared by mixing phosphatidyl-ethanolamine, phosphatidyl-serine, phosphatidyl-choline, and cardiolipin (Avanti Polar Lipids) in a ratio of 5:4:1:0.3 (v/v). The phospholipids were dried under N2 and re-suspended in n-decane to a final concentration of 25 mg/mL. The cis/trans chambers contained symmetrical solutions of 10 mM HEPES, 200 mM KCl and 100 µM CaCl2 at pH 7.4. The cis chamber was held at virtual ground and the trans chamber was held at the command voltages. SKCa protein was added into the cis chamber. The effect of the SKCa blocker apamin, 100 nM, on channel activity was tested by adding it to the cis chamber in the presence of 100 µM CaCl2. To test for Ca2+ dependence of the SKCa channel, [Ca2+] was serially increased (1, 50 and 100 µM) in the cis chamber. Currents were sampled at 5 kHz and low pass filtered at 1 kHz using a voltage clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B, Molecular Devices) connected to a digitizer (DigiData 1440, Molecular Devices), and recorded in 1 min segments. The pClamp software (version 10, Molecular Devices) was used for data acquisition and analysis. Additional analyses were conducted using Origin 7.0 (OriginLab).

2.15. Matrix K+ measured in isolated mitochondria

Cardiac isolated mitochondria (0.5 mg protein/mL) were suspended in respiration buffer containing 130 mM KCl, 5 mM K2HPO4, 20 mM MOPS, 2.5 mM EGTA, 1 µM Na4P2O7, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.15 adjusted with KOH. Buffer [Ca2+] was less than 100 nM as assessed by the fluorescence dye indo 1. Matrix K+ was monitored during state 4 respiration (200 µM ATP) with substrate Na-pyruvate (10 mM) in a cuvette-based spectrophotometer (QM-8, Photon Technology International, PTI) with light (λex 340 and 380 nm; λex 500 nm) in the presence of the fluorescence dye PBFI (1 µM per mg/mL protein, Invitrogen) [50]. PBFI, in the acetylated methyl-ester (AM) form, was added to the mitochondrial preparation and incubated at 25°C for 20 min. After entering the matrix PBFI is retained in the matrix after it is cleaved from the methyl-ester. During the last pellet wash the extra-matrix residual dye was washed out. Most experiments were conducted in the presence of 500 µM quinine to block the mitochondrial K+/H+ exchanger (mKHE) and extrusion of the K+ [50]. In some experiments 0.25 nM valinomycin, a K+ ionophore, was given to verify an increase in matrix K+ influx, and to be used as a reference for the change of K+ influx by DECB ± its antagonist UCL1684.

3. Results

3.1. DCEB protects isolated heart against IR injury

Spontaneous heart rate averaged 242±13 beats/min before ischemia for all groups; this was not statistically different at 120 min reperfusion for all groups (data not displayed). If ventricular fibrillation (VF) occurred, it was only once within the first 5 min of reperfusion in any heart; all were converted to sinus rhythm with intracoronary lidocaine. After 5 min reperfusion all hearts remained in sinus rhythm, some with occasional pre-ventricular excitations. In data not displayed the incidence of VF on reperfusion was CONTROL 100%, DCEB+TBAP 100%, DCEB 76%, DCEB+TRAM 72%, DCEB+PAX 77%, DCEB+GLIB 77% (all nonsignificant vs. control group).

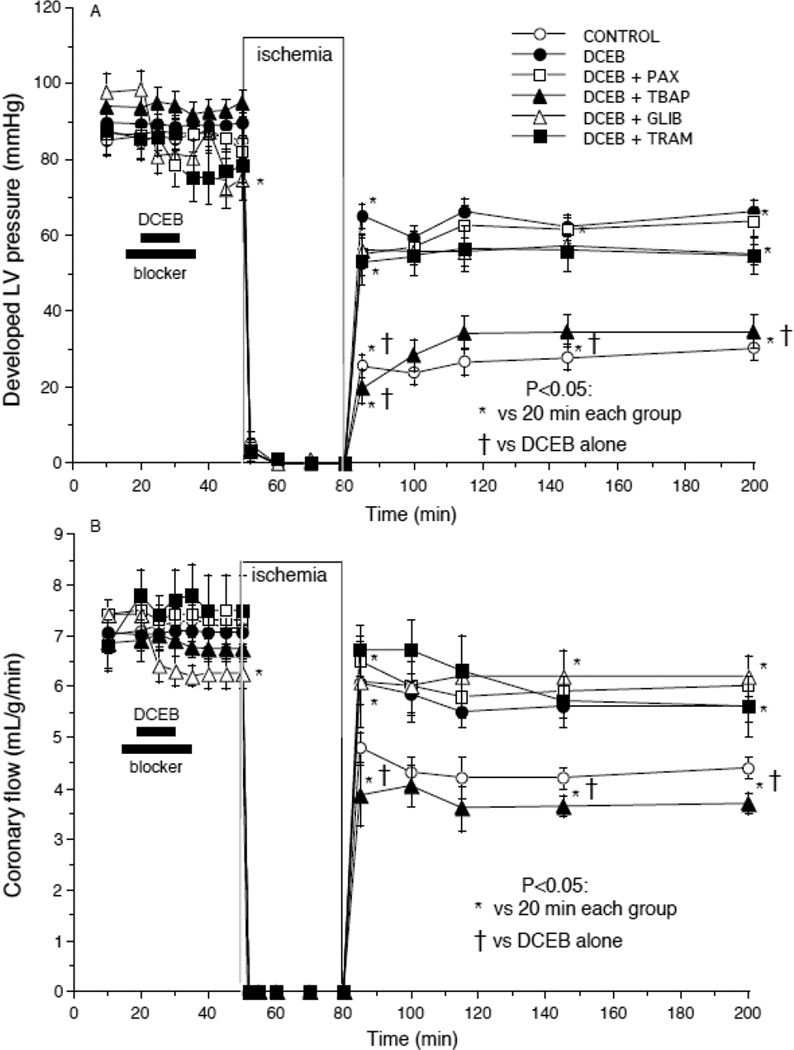

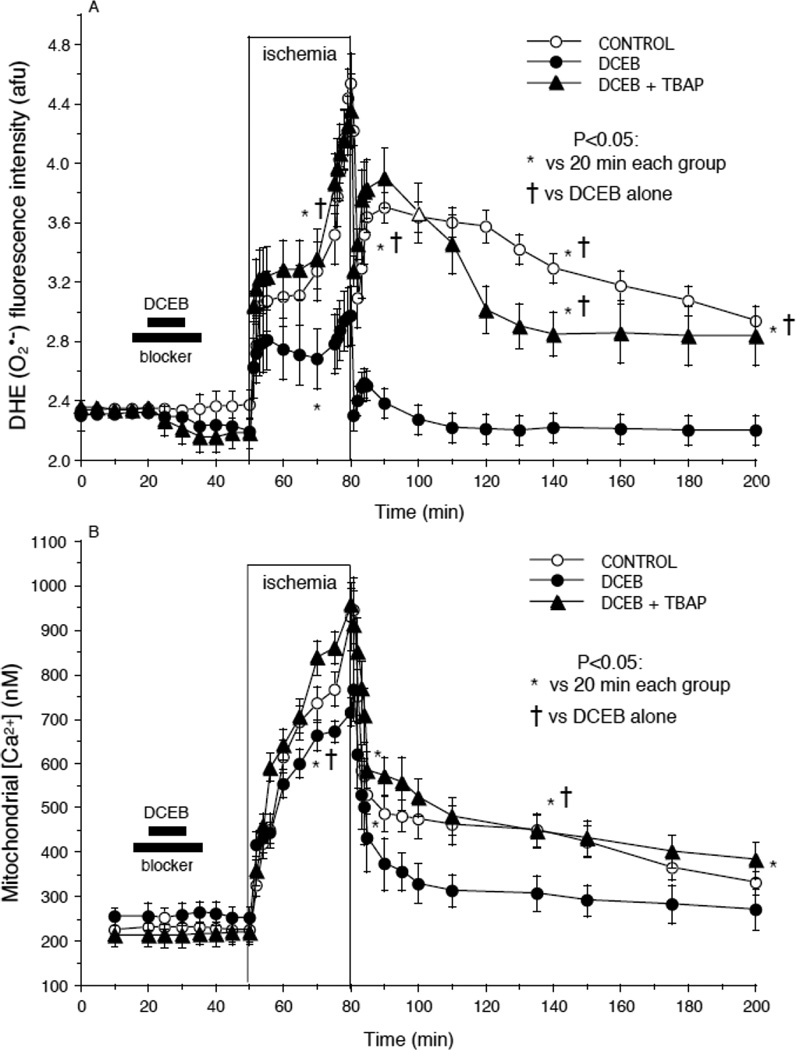

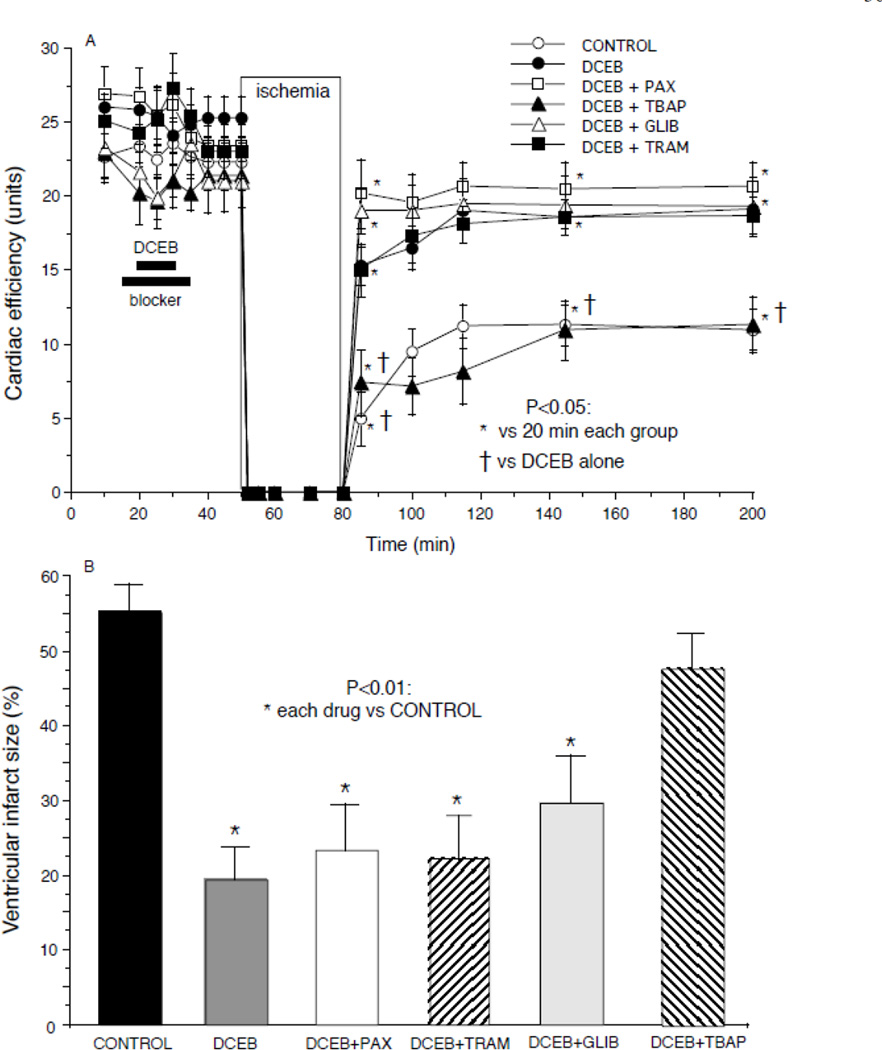

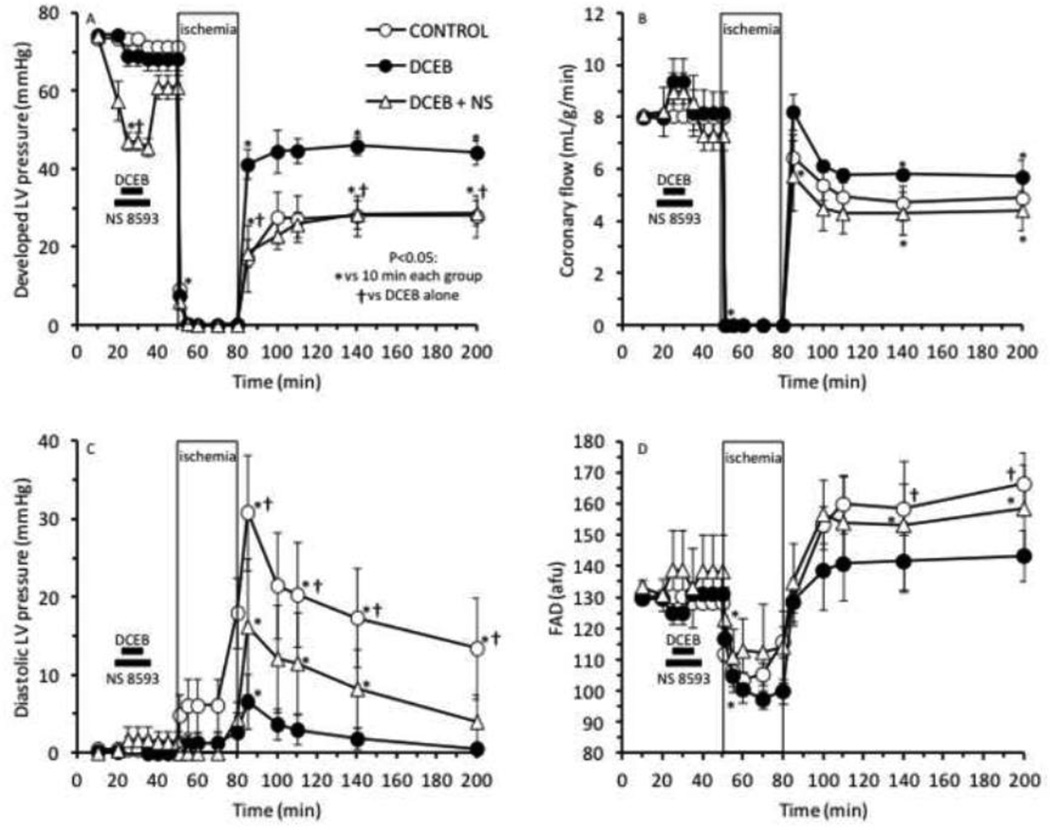

Figs. 1–4 show the marked degree of dysfunction or damage in the untreated control group during and after global ischemia and the beneficial effects of PPC elicited by DCEB treatment before ischemia. Developed LVP (Fig. 1A) and coronary flow (Fig. 1B) were reduced in each group after ischemia compared to before ischemia, but these changes were much larger in the CONTROL and DCEB+TBAP groups than in the other groups. Similarly, cardiac efficiency (Fig. 2A) was lower and infarct size (Fig. 2B) was largest in the CONTROL and DCEB+TBAP groups than in all other groups. The drug treatments before ischemia had no effects by themselves on any of the functional variables. These figures indicate that these variables were markedly improved on reperfusion after treatment with DCEB and that these improvements were reversed by TBAP, but not by PAX, TRAM, or GLIB.

Fig. 1.

Improved (A) developed (systolic-diastolic) LV pressure and (B) coronary flow after preconditioning with 3 µM DCEB. Note that TBAP (synthetic superoxide dismutase mimetic) reversed the protective effects of DCEB whereas antagonists of big (PAX, paxilline) and intermediate (TRAM) conductance KCa channels did not.

Fig. 4.

Reduced (A) O2•− (DHE fluorescence) and (B) mitochondrial [Ca2+] (indo 1 fluorescence) after preconditioning with DCEB. Note the increases in these signals during ischemia and the slow decline during reperfusion. DCEB attenuated the increase in these signals during ischemia and reperfusion and this was reversed by TBAP.

Fig. 2.

A: Improved cardiac efficiency (developed LV pressure (mmHg)•heart rate (beats/min))/MVO2 (µL O2•g−1•min−1) after preconditioning with DCEB. Note that TBAP reversed the protective effects of DCEB whereas antagonists of big (PAX) and intermediate (TRAM) conductance KCa channels did not. B: Marked decrease in infarct size after preconditioning with DCEB. Note that TBAP reversed the anti-infarction effect of DCEB whereas antagonists of big (PAX) and intermediate (TRAM) conductance KCa channels and KATP channels (glibenclamide, GLIB) did not.

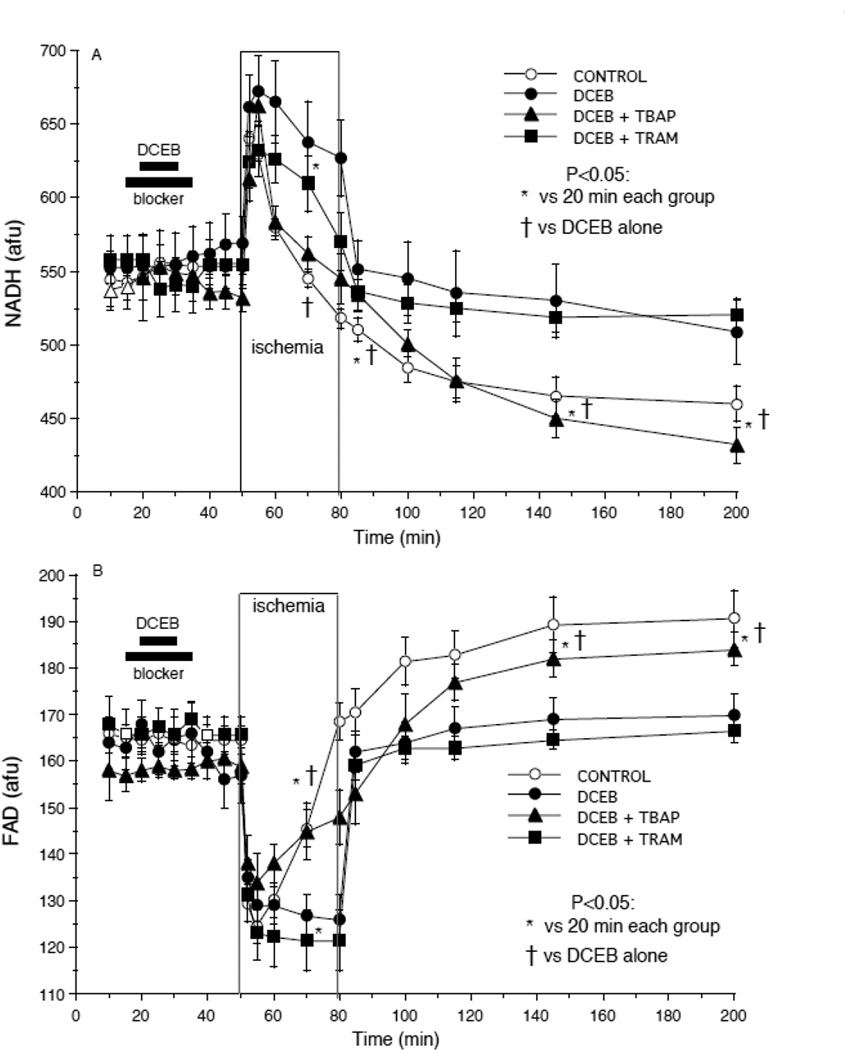

There was no detectable change in NADH and FAD autofluorescence in any group by drugs given and terminated before ischemia (Fig 3A,B). NADH (Fig. 3A) remained higher at the end of ischemia and fell less during reperfusion after treatment with DCEB; this was reversed by TBAP but not by TRAM. FAD remained lower at the end of ischemia and rose less during reperfusion after treatment with DCEB (Fig 3B); this was reversed by TBAP, but not by TRAM. In other experiments there were no detectable change in NADH or FAD on reperfusion after DCEB+PAX or +GLIB treatment vs. DCEB alone.

Fig. 3.

Improved redox state (A: NADH and B: FAD autofluorescence) after preconditioning with DCEB. Note the inverse changes in NADH and FAD during ischemia and reperfusion and the more normalized responses in the DCEB group. TBAP reversed the protective effects DCEB whereas paxilline (PAX), an antagonist of big conductance BKCa channels did not.

DHE fluorescence (O2•− formation) (Fig. 4A) and indo 1 fluorescence (m[Ca2+]) (Fig. 4B) rose markedly in each group during the course of ischemia. TBAP caused a small, but insignificant, decrease in DHE fluorescence before ischemia. TBAP reversed the effect of DCEB to reduce O2•− and m[Ca2+] on reperfusion. Other experiments (not shown) did not demonstrate detectable changes in ROS formation or m[Ca2+] on reperfusion after DCEB+PAX, +GLIB or +TRAM treatments vs. DCEB alone.

In companion experiments (Fig. 5A–D) the protective effects of DCEB were abolished or antagonized by the SKCa channel antagonist NS8593, thus demonstrating that DCEB protected via activation of SKCa channels. DCEB–induced maintenance of developed LVP was completely blocked, while the maintenance of coronary flow and the reduction of diastolic LVP and FAD oxidation by DCEB were all markedly reversed by NS8593. NS8593 alone significantly depressed developed LVP when given before ischemia and tended (non significantly) to slightly increase coronary flow, possibly indirectly due to reduced ventricular compression; thus the small increase in flow (Fig. 5B) noted in the presence of DCEB is due to NS8593 rather than DCEB. Generally, cardiac depression before ischemia is cardioprotective, but giving NS8593 with DCEB before ischemia, resulted in a worsening of contractile function on reperfusion.

Fig. 5.

Improved (A) developed LV pressure and coronary flow (B), and decreased diastolic LV pressure (C) and FAD oxidation (D), after preconditioning with DCEB. Note that 10 µM NS8593 (a specific SKCa antagonist) abrogated these protective effects of DCEB.

These studies demonstrated that DCEB had protective effects against cardiac IR injury mediated by the SKCa channel, and that cardiac mitochondria appeared to be involved in mediating this protection. Studies were then undertaken to isolate and identify the target of DCEB, the SKCa protein, in cardiac isolated mitochondria and in IMM, and to verify the functionality of the protein in an artificial lipid bilayer.

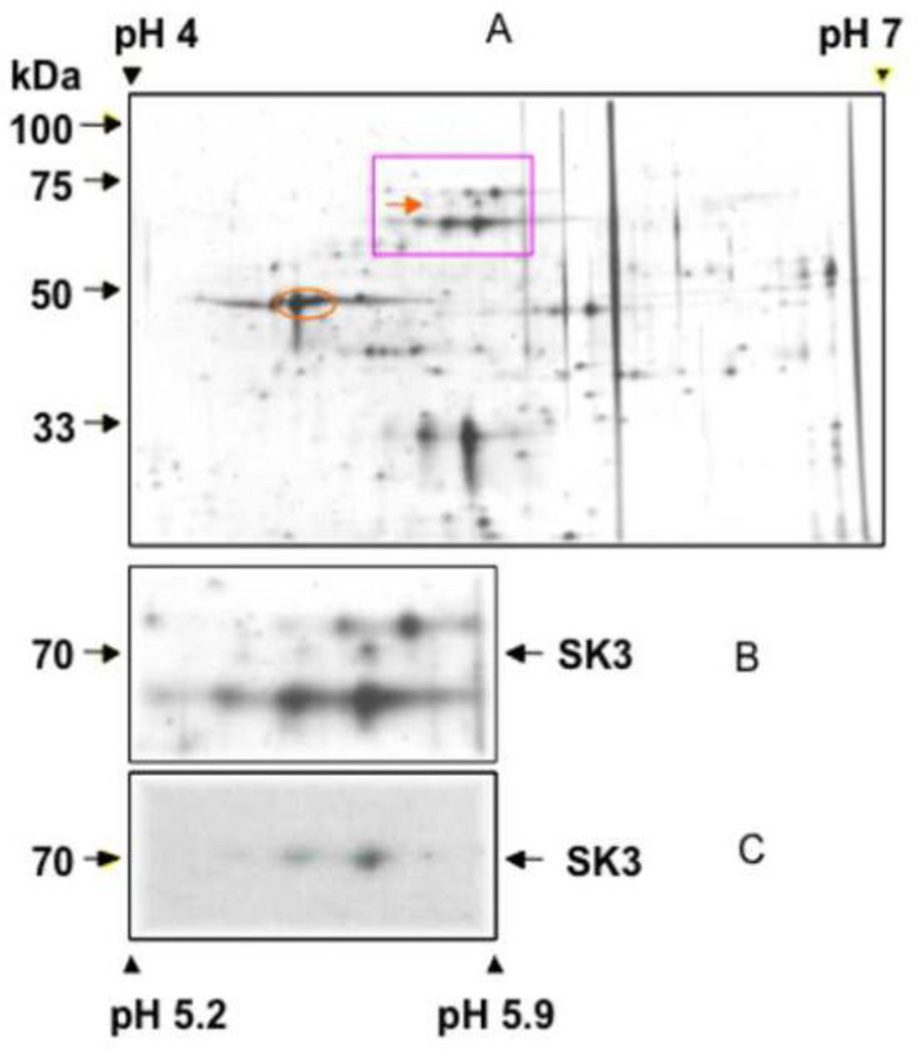

3.2. Isoelectric focusing and peptide sequences identify SKCa in isolated IMM

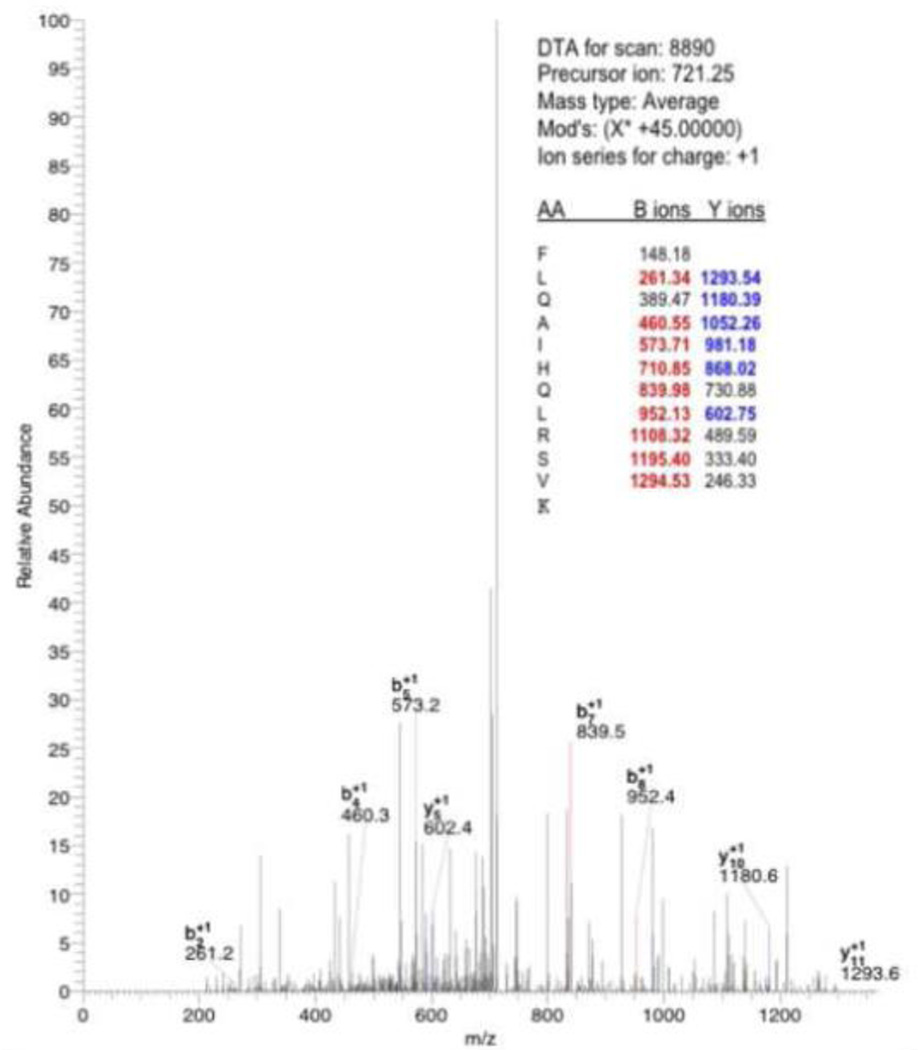

IMM protein, enhanced for calmodulin-binding residues, was separated by 2-D electrophoresis after silver staining. Three peptide spots of approximately 70 kD at pH 5.2–5.5 were detected as SKCa using the anti KCa2.3 (anti-hSK3) (Fig. 6, panels a–c). Complementing this finding, a KCa2.3 protein was identified by ESI-mass spectrometry from five matching peptides with an amino acid coverage of 10.73% (Table). There was no evidence for peptides matching Na+/K+ ATPase or Ca2+ ATPase suggesting the absence of sarcolemmal and t-tubular membranes in the mitochondrial fraction. The mass spectrum of one of these peptide sequences is shown (Fig. 7). These results demonstrated that SKCa channels were present in the IMM.

Fig. 6.

Identity of small-conductance KCa channels in IMM from guinea pig heart. Top panel: Silver staining of calmodulin affinity column-purified protein fractions after 2-D gel fractionation. The square indicates the area of interest, which was magnified and is shown in the middle panel. The arrows indicate position of KCa2.3 proteins. Bottom panel: Western blot with an antibody targeting SKCa (anti-hSK3) channel detection at 3 spots at 70 kDa (arrow) between pH 5.2 and 5.5. Negative control was done by pre-incubating KCa2.3 antibodies with blocking peptide (not shown).

Table.

Protein coverage matched to an SKCa subunit 6 isoform by NP LC/SI mass spectrometry.

| Reference: gi|21361129|ref|NP_002240small conductance calcium-activated potassium protein 6. Database: C:\Xcalibur\database\human_ref.fasta Number of Amino Acids: 736 Average MW: 82026.4 pI:10.07. (matched peptide sequences). Aka: SKCa3, KCNN3 | |||||||

| Note the matching of peptide sequences covering subunit 6 and calmodulin binding domain. | |||||||

| MDTSGHFHDS | GVGDLDEDPK | CPCPSSGDEQ | QQQQQQQQQQ | QPPPPAPPAA | |||

| PQQPLGPSLQ | PQPPQLQQQQ | QQQQQQQQQQ | QQQQQPPHPL | SQLAQLQSQP | |||

| VHPGLLHSSP | TAFRAPPSSN | STAILHPSSR | QGSQLNLNDH | LLGHSPSSTA | |||

| TSGPGGGSRH | RQASPLVHRR | DSNPFTEIAM | SSCKYSGGVM | KPLSRLSASR | |||

| RNLIEAETEG | QPLQLFSPSN | PPEIVISSRE | DNHAHQTLLH | HPNATHNHQH | |||

| AGTTASSTTF | PKANKRKNQN | IGYKLGHRRA | LFEKRKRLSD | YALIFGMFGI | |||

| VVMVIETELS | WGLYSKDSMF | SLALKCLISL | STIILLGLII | AYHTREVQLF | code: | ||

| VIDNGADDWR | IAMTYERILY | ISLEMLVCAI | HPIPGEYKFF | WTARLAFSYT | BOLD = peptides identified | ||

| PSRAEADVDI | ILSIPMFLRL | YLIARVMLLH | SKLFTDASSR | SIGALNKINF | blue = transmembrane region 1 | ||

| NTRFVMKTLM | TICPGTVLLV | FSISLWIIAA | WTVRVCERYH | DQQDVTSNFL | green = selectivity pore | ||

| GAMWLISITF | LSIGYGDMVP | HTYCGKGVCL | LTGIMGAGCT | ALVVAVVARK | grey = transmembrane region 6 | ||

| LELTKAEKHV | HNFMMDTQLT | KRIKNAAANV | LRETWLIYKH | TKLLKKIDHA | yellow = calmodulin binding domain | ||

| KVRKHQRKFL | QAIHQLRSVK | MEQRKLSDQA | NTLVDLSKMQ | NVMYDLITEL | (CaMD) | ||

| NDRSEDLEKQ | IGSLESKLEH | LTASFNSLPL | LIADTLRQQQ | QQLLSAIIEA | |||

| RGVSVAVGTT | HTPISDSPIG | VSSTSFPTPY | TSSSSC | ||||

| Protein Coverage: | MH+ | % Mass | AA | % AA | |||

| RALFEKR | 920.09 | 1.12 | 279 – 285 | 0.95 | |||

| GVCLLTGIMGAGCTALVVAVVARKLELTK | 2888.59 | 3.52 | 527 – 555 | 3.94 | |||

| HVHNFMMDTQLTKR | 1759.05 | 2.14 | 559 – 572 | 1.90 | |||

| IKNAAANVLRETWLIYK | 2004.36 | 2.44 | 573 – 589 | 2.31 | |||

| FLQAIHQLRSVK | 1440.72 | 1.76 | 609 – 620 | 1.63 | |||

| Totals: | 8936.73 | 10.89 | 79 | 10.73 | |||

Letters in bold represent those peptides identified based on their MS/MS profiles. The list below the sequence represents all peptides identified by mass spectrometry. The gray-filled sections of the bar above the sequence represent the position of the identified peptides in the sequence. Also shown is the molecular weight and pI of the protein. There are 4 peptides covering 10.89% of the total amino acids of this protein segment. Note that the mass spectral analysis showed a 70% amino acid coverage in the calmodulin binding domain (CaMBD), a peptide sequence just before (N terminus) the a pore forming subunit 1, and the entire sequence of subunit 6.

Fig. 7.

Identification of one peptide, FLQAIHQLRSVK (in CaMBD), from data obtained using nano-LC/MS. The b-ions and y-ions are fragment masses of the above peptide upon its collision fragmentation. Peptides were identified by searching the rodent subset of Uniprot databases. This protein was identified based on the 5 matching peptide sequences shown in the Table.

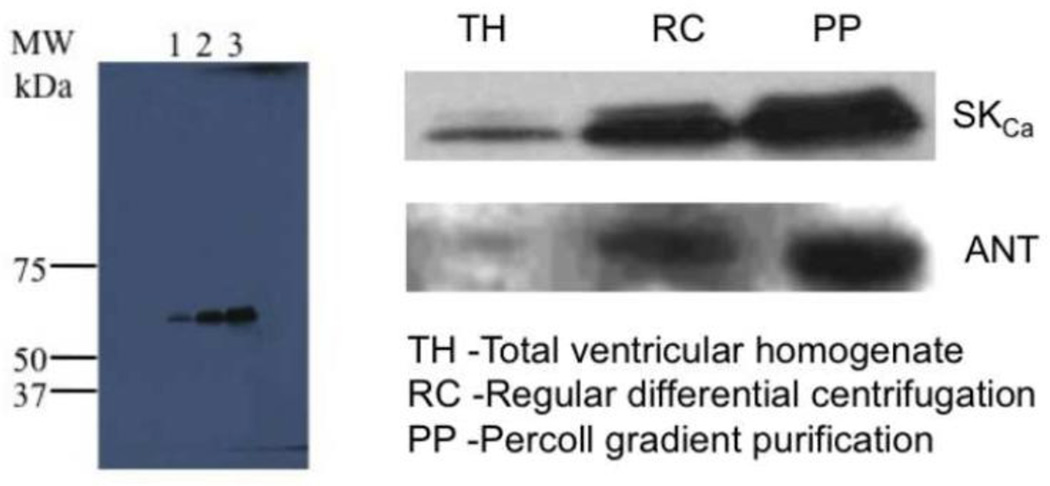

3.3. Western blots of serially purified mitochondria demonstrate SKCa channel protein

Mitochondria exhibited increasing band densities for both SKCa and ANT protein (Fig. 8) when enriched by Percoll gradient serial purification. This furnished compelling Western blot evidence that SKCa channel protein increases in abundance with ANT, which is present only in the IMM.

Fig. 8.

Western blots of serially purified mitochondria showed increasing amounts of SKCa protein. Equal amounts of protein were loaded in the gel. Total homogenate (lane 1, TH) showed least band intensity, followed by mitochondria isolated by differential centrifugation (lane 2 RC); mitochondrial purified further by Percoll gradient purification (lane 3, PP) had the highest band intensity. Protein bands of SKCa are approximately 68 KDa. Purity of mitochondria was followed by assaying the increased amount of ANT, along with SKCa, protein in their respective purification fractions.

3.4. Immunochemistry and confocal microscopy identify SKCa channel protein in mitochondria

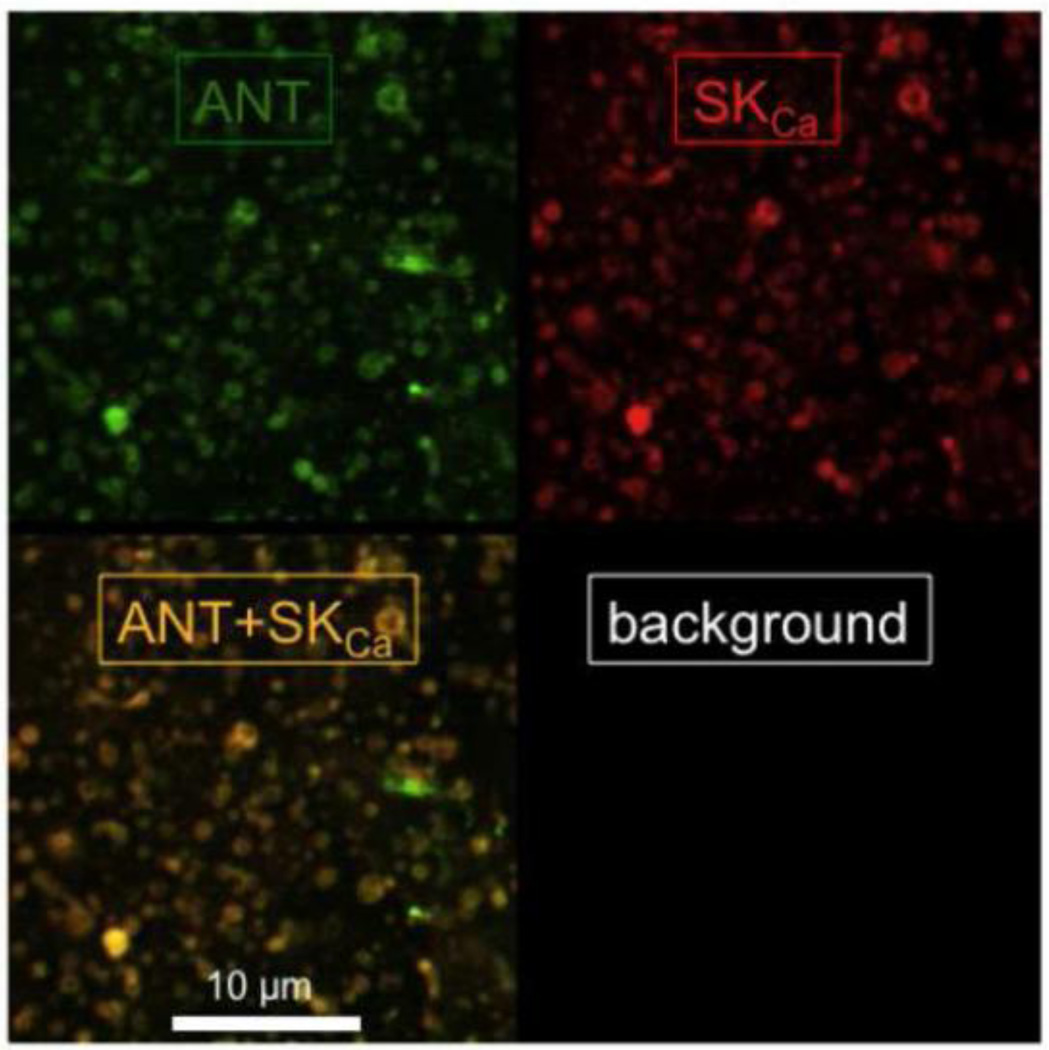

Confocal microscopy was used to localize SKCa protein to intact mitochondria. Cardiac mitochondria were visualized as stained by an antibody against ANT (green), and SKCa channel protein was visualized using the anti-KCa2.2 (anti-SK2) antibody (red) (Fig. 9). Overlay of the two images (yellow) shows co-localization of SKCa and ANT proteins in cardiac mitochondria. Since ANT localizes only to the IMM, this suggested that SKCa channel protein also localizes to the IMM.

Fig. 9.

SKCa protein identified in isolated mitochondria and visualized by confocal microscopy. Overlay of the two images (anti-ANT, green and anti-SKCa, red) demonstrates co-localization (yellow) of the SKCa protein in mitochondria.

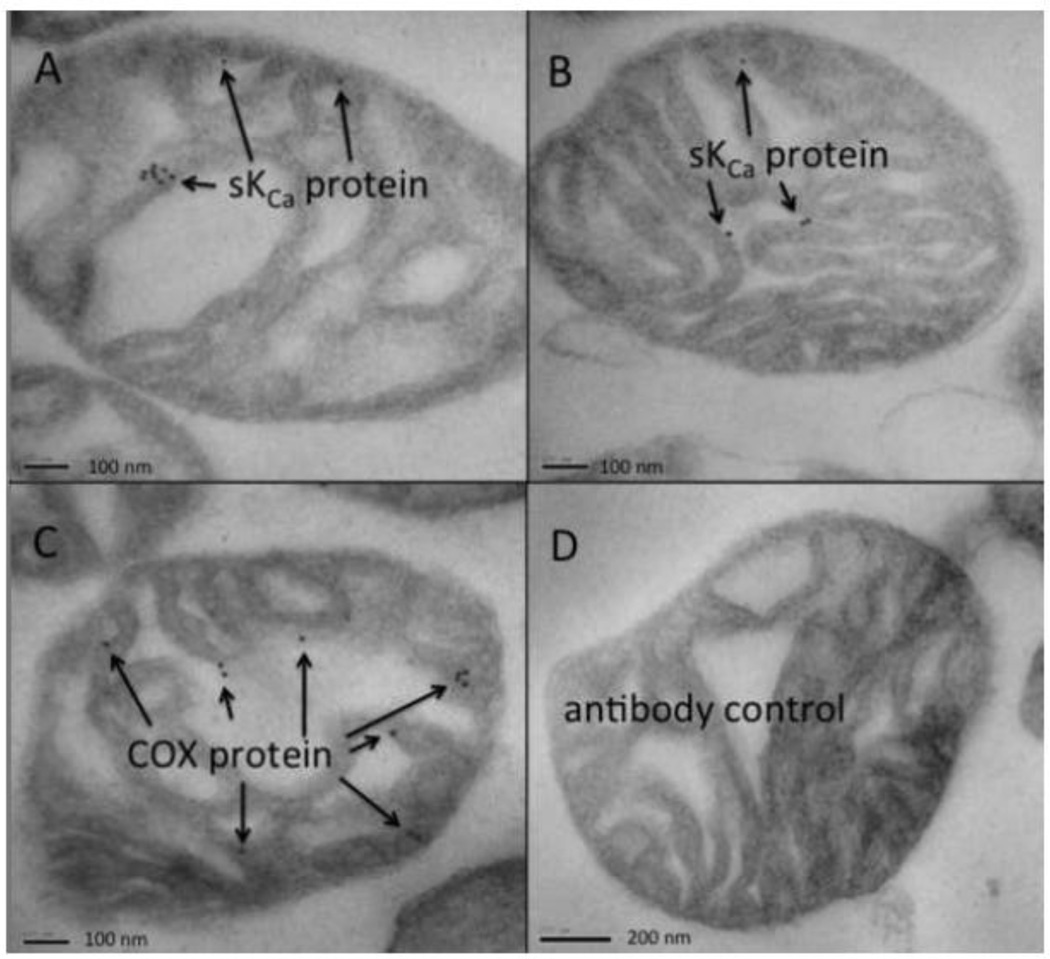

3.5. Immuno-gold labeling and EM show localization of SKCa channels in mitochondrial matrix

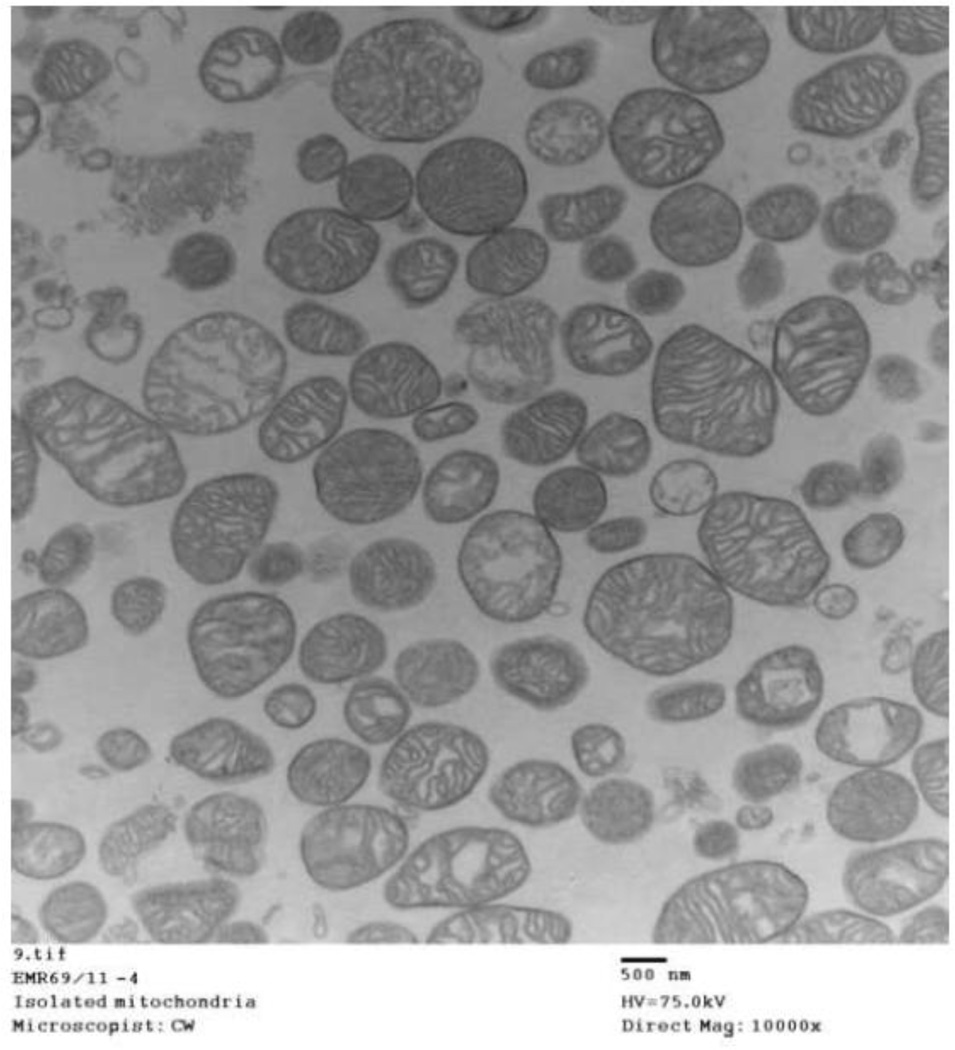

To further confirm the presence and localization of the SKCa channels on the IMM, mitochondria were visualized at high resolution using IEM. A large field EM view shows largely normal appearing cardiac mitochondria with intact outer membranes and cristae (Fig. 10). Enhanced resolution of immuno-gold labeled mitochondria show gold particles attributed to SKCa channels (Fig. 11A, B) or cytochrome c oxidase (COX) (Fig. 11C) within the matrix; in detailed examination of electron micrographs approximately 50% contained at least 2 gold particles. Negative controls (Fig. 11D) (non-immune rabbit polyclonal serum showed no gold particles in any field. Figs. 8, 9, and 11 confirm that SKCa channels are located in mitochondria and most likely in the IMM.

Fig. 10.

Electron micrograph of isolated mitochondria. Larger field view of untreated mitochondria shows largely intact structural characteristics after isolation from guinea pig hearts.

Fig. 11.

Immuno-electron microscopy of isolated cardiac mitochondria. A, B: SKCa protein as visualized in two mitochondria; 50% of all viewed mitochondria exhibited gold labeling. Gold labeling was obtained by immuno-gold secondary antibody conjugated to primary rabbit polyclonal anti-KCa2.2 (anti-SK2). C: Positive control was anti-cytochrome c oxidase (COX1) conjugated to goat anti-rabbit or mouse conjugated to colloidal gold; each mitochondrion in a large field view exhibited at least two gold particles. D: Negative control was only secondary polyclonal rabbit antibody conjugated to gold; there was no gold labeling of any mitochondria in any views.

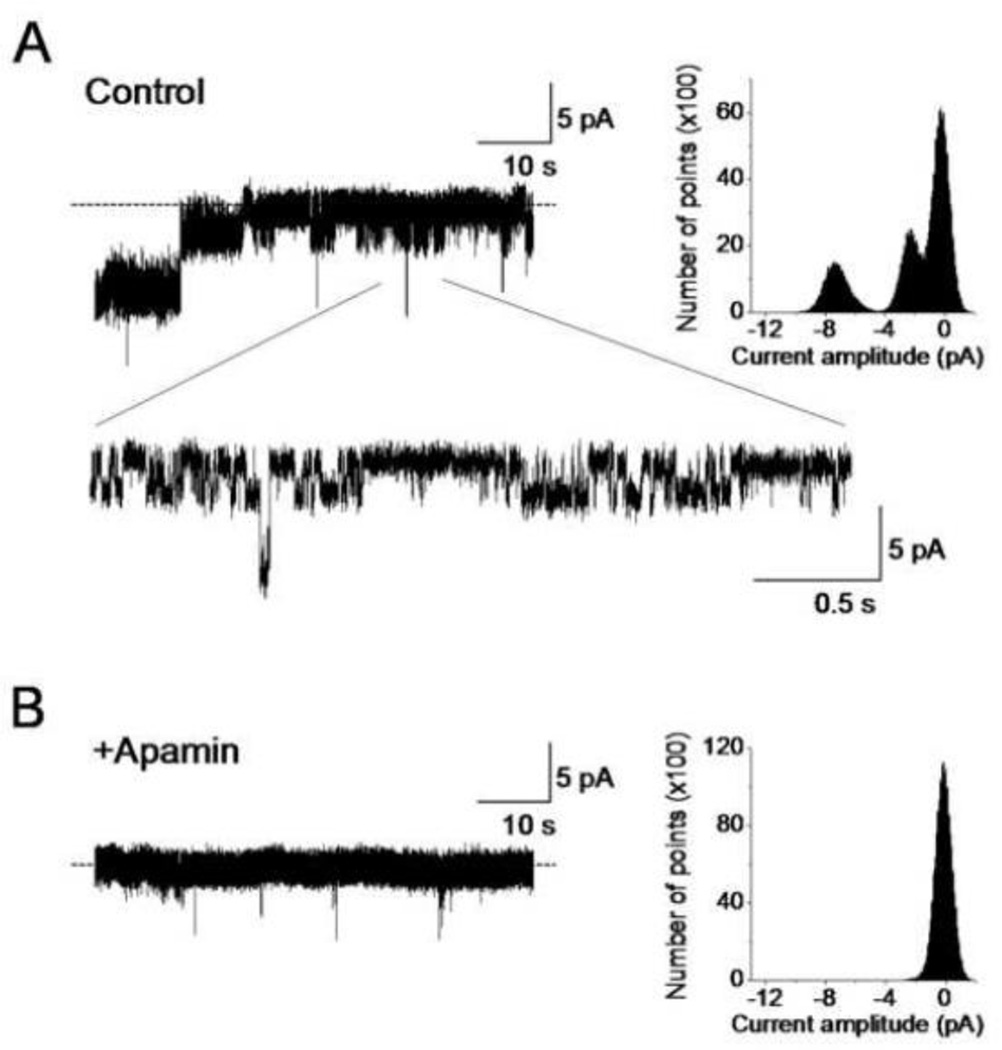

3.6. Mitochondrial SKCa protein forms a functional channel

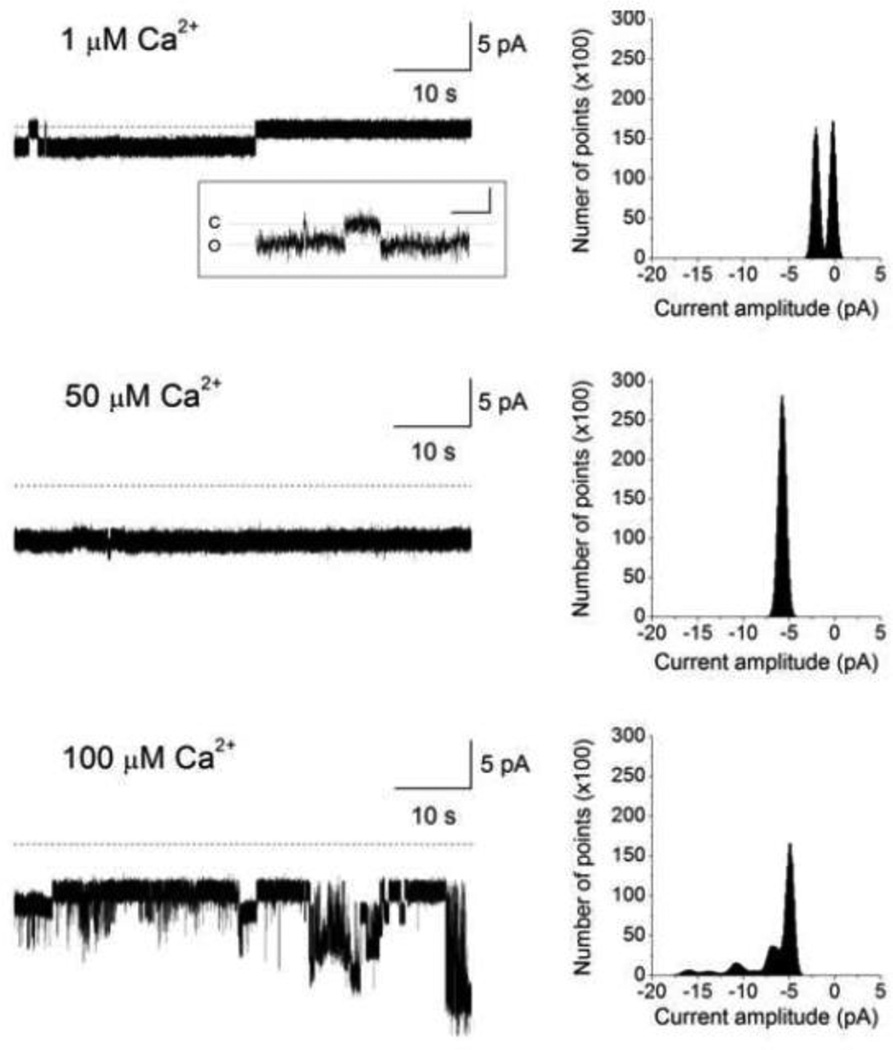

To test if purified mitochondrial SKCa protein forms a functional channel, SKCa protein, isolated as noted above (2.9), was incorporated into a planar lipid bilayer for electrophysiological measurements. In the lipid bilayer, the SKCa protein exhibited robust activity in the presence of 100 µM [Ca2+] (Fig. 12A). Two conducting states with chord conductances of 230 and 730 pS were observed when recorded in an ionic condition of equimolar 200 mM KCl. Adding apamin blocked channel activity (Fig. 12B) indicating that the functional channel formed by the mSKCa protein was inhibited by this SKCa channel blocker. The mSKCa channel protein incorporated into the planar lipid bilayer also displayed Ca2+–dependent activity (Fig. 13). The mSKCa channel exhibited increasing activity as [Ca2+] was serially increased from 1 to 100 µM. As shown, channel open probability (Po) increased from Po=0.5 at 1 µM [Ca2+] to Po=1.0 at 50 and 100 µM Ca2+. A notable observation was also the [Ca2+] dependent increase in the number of conducting states. At 1 µM Ca2+ the predominant conductance was 180 pS; however, at 50 and 100 µM Ca2+ multiple, larger conductances were revealed. Thus, as [Ca2+] was increased the mSKCa channel exhibited greater conducting states while at lower [Ca2+], low conductance states dominated. This observation is further supported by the existence of a smaller conductance channel of 70 pS which was detected, albeit infrequently, at 1 µM Ca2+ (Fig. 13, inset).

Fig. 12.

mSKCa channel protein activity. Purified mitochondrial SKCa protein was incorporated into a planar lipid bilayer and channel activity was recorded at a membrane potential of −10 mV in the presence of 100 µM CaCl2. Dotted lines denote zero current levels and downward deflections denote channel openings. A: Two primary conductance states with chord conductances of 230 and 720 pS were observed under control conditions. The current recording is also depicted in an expanded time scale. Corresponding all-points amplitude histogram is also shown. B: Channel activity was blocked by adding100 nM apamin.

Fig. 13.

mSKCa channel sensitivity to [Ca2+]. Channel activity of purified mitochondrial SKCa protein, incorporated into the planar lipid bilayer, was recorded at a membrane potential of −10 mV. [Ca2+] was incrementally increased; dotted lines denote zero current levels and downward deflections denote channel openings. The corresponding all-points amplitude histogram is also shown. The predominant conductance was 180 pS when channel activity was recorded in 1 µM [Ca2+]. However, we have also observed, infrequently, a smaller conducting state of 70 pS at 1 µM [Ca2+]. A sample tracing is depicted in the inset in which the calibration for the x- and y-axis is 200 ms and 1 pA, respectively; C and O denote the closed and open states, respectively.

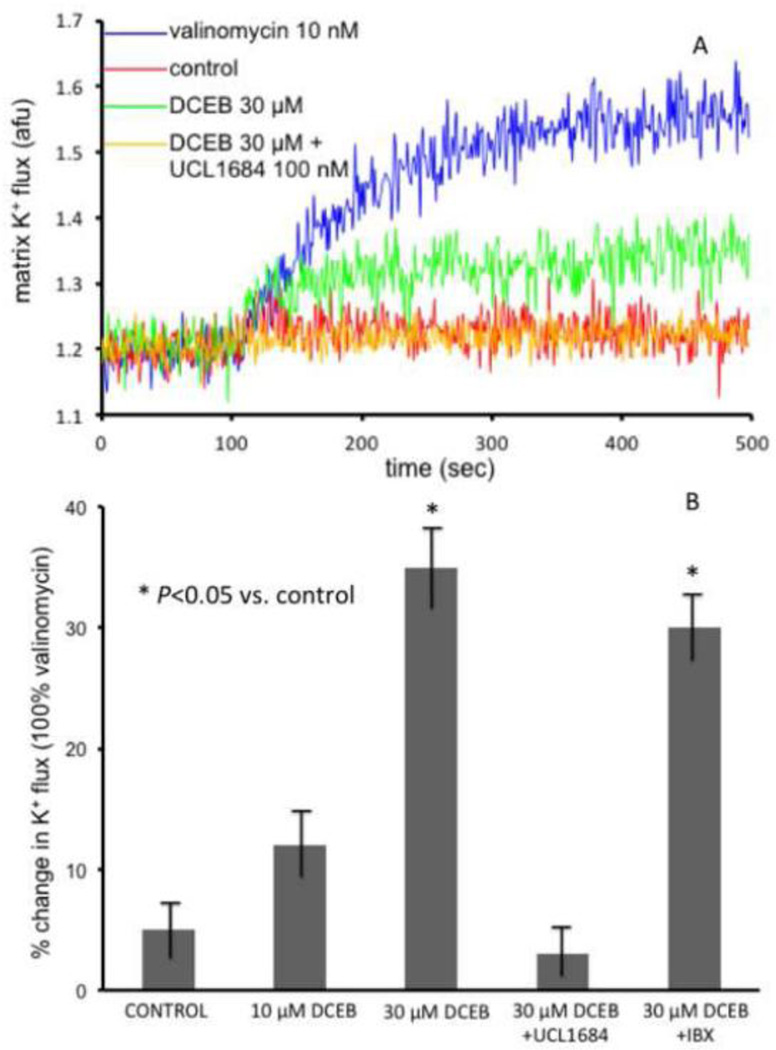

3.7. DCEB–induced increased matrix [K+] is blocked by UCL1684

The consequence of opening of SKCa channels to changes in mitochondrial matrix [K+] was also determined. In isolated mitochondria the SKCa channel opener DCEB increased matrix [K+] in the presence of quinine to inhibit KHE and thus counter K+ extrusion (Fig. 14A, B). The observed influx of K+ into the matrix was confirmed by similar K+ influx induced by the K+ ionophore valinomycin. The effect of DCEB was blocked by UCL1684 (a SKCa blocker) but not by iberotoxin (IBX) (a blocker of BKCa but not SKCa channels) (Fig. 14B). The increase in matrix K+ uptake induced by DCEB and blocked by UCL1684 (Fig. 14), and the Ca2+ induced increases in K+ current and inhibition by apamin in lipid bilayers (Figs. 12, 13) functionally linked DCEB’s cardiac effects to SKCa channels presence and activity in cardiac mitochondria.

Fig. 14.

A: Sample time tracing showing effect of 30 µM DCEB in the presence of 500 µM quinine (KHE inhibitor) to increase matrix K+ (PBFI fluorescence) in mitochondria isolated from a guinea pig heart. No change was observed in the absence of quinine. The DCEB-induced increase in K+ flux was completely blocked by 100 nM UCL1684. Note larger but similar effect of 1 nM valinomycin, a K+ ionophore, to DCEB B: Summary effects (n = 10 mitochondrial preparations) of DCEB, expressed as a % of valinomycin effect, on increasing matrix K+ in the presence of quinine. This increase in K+ was blocked by SKCa channel blocker UCL1684 but not by 200 nM iberiotoxin (IBX), a blocker of BKCa channels.

4. Discussion

Our results suggest a novel role for the SKCa channel in cardiac myocyte preconditioning, likely mediated via altered mitochondrial function due to opening of SKCa channels located in myocyte mitochondrial IMM (mSKCa). Our comprehensive experimental approach shows that the well-known SKCa (and IKCa) channel activator DCEB preconditioned hearts and that this was fully reversible by bracketing DCEB with the intra-matrix O2•− dismutator TBAP. Cardioprotective effects of DCEB were attributed specifically to activation of SKCa channels and not to activation of KATP, IKCa, or BKCa channels because NS8593, but not GLIB, TRAM, or PAX blocked its effects. DCEB increased K+ flux in isolated mitochondria and the purified SKCa protein formed a functional channel when incorporated into lipid bilayers. Thus mSKCa channel opening, similar to that of mKATP and mBKCa channel opening, appears to induce PPC by an as yet unclear mechanism related to enhanced matrix K+ entry. Moreover, mitochondrial-derived O2•− is required to initiate PPC by DCEB, because if O2•− is rapidly converted to downstream products the protection by DCEB is lost.

Just as we supported our evidence that the SKCa channel is specifically involved in PPC of isolated hearts, we sought to support specifically that the mSKCa channel was associated with cardioprotection. To provide evidence that DCEB’s has protective effects mediated by mSKCa channels, it was necessary to rigorously identify mSKCa protein in purified mitochondria, and specifically in the IMM. To do so we utilized Western analysis and immuno-histochemistry, confocal microscopy, electron microscopy, and mass spectrometry of purified mitochondrial proteins derived from IMM. Organelle location was accompanied by channel functionality in isolated mitochondria and in lipid bilayers, thus supporting that this channel may play a role in cardiac protection via a mitochondrial mechanism. Overall our study indicates that the SKCa channel, localized in the cardiac cell IMM, mediates the effect of DCEB in preconditioning of the heart via a mitochondrial mechanism related to mK+ flux and O2•− generation.

The dequalinium analogue, UCL1684, is known to block opening of apamin-sensitive SKCa channels in mammalian cell lines [51]. We support involvement of the mitochondrion in DCEB’s PPC effect because TBAP could block the protective functional effects of DCEB as well as block DCEB’s effect to decrease ischemia-induced levels of mCa2+ and of O2•−, presumably generated by complexes along the electron transport system [52]. Also, DCEB directly induced an increase in matrix K+ uptake. Moreover, since DCEB had no significant effects on coronary flow (Fig. 1), automaticity, or contractility, this suggests DCEB had no effect on endothelial/vascular or ventricular cell function. Overall, our results demonstrate the marked cardioprotective effects after preconditioning with DCEB and implicate mSKCa channel opening and generation of O2•−, or its products, as initiators and inhibitors of mitochondrial as well as cardiac myocyte PPC.

The improvement in cardiac function by DCEB was accompanied by reduced formation of O2•−, reduced m[Ca2+], and improved redox state (more normal NADH and FAD levels) during both ischemia and reperfusion. These cardioprotective effects of DCEB were blocked only by either TBAP or NS8593. We suggest that initial formation of O2•− is essential for the triggering mechanism of PPC by mSKCa channel activation. However, a downstream product of O2•−, e.g. H2O2, might actually mediate the protective effects of DCEB. A similar dependence for O2•− has been observed for the mKATP channel opener diazoxide [24], the BKCa channel opener NS1619 [4], and volatile anesthetics [27, 34]. Drug lipophilicity with mitochondrial membrane penetration may be an important common denominator for the activity of drugs such as diazoxide, a putative mKATP channel agonist, and DCEB.

4.1 Distribution and function of Ca2+ -sensitive K+ channels

The cell membranes of vascular smooth muscle, neural, and secretory cells contain large conductance (200–300 pS). i.e. Big Ca2+-sensitive K+ (BKCa, aka maxi-KCa) channels that when opened produce vasodilation, hyperpolarization, and secretion. BKCa channel opening is activated by increased [Ca2+]i and by cell membrane depolarization [53]. Activation of BKCa over a range of [Ca2+] is mediated at several binding sites within the channel [54] so that there is a wide range of [Ca2+] responsiveness (Ka 10–1000 µM) [55]. As K+ exits the cell with BKCa channel opening, this elicits cell membrane repolarization or hyperpolarization, which in turn reduces Ca2+ entry by closing voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Altered redox potential in smooth muscle [56] suggested mitochondrial involvement. Xu et al. [57] first furnished evidence that BKCa channels are located in cardiac mitochondria.

The membrane bound, but non-voltage-gated, KCa channels, i.e., SKCa and IKCa [11], are gated by Ca2+ and other factors. SKCa (a.k.a. KCa2.1–2.3, KCNN1–3 -gene symbol) channels have characteristics that largely differ from the BKCa channels i.e. small unitary conductance (10–30 pS), voltage independence with activation only by Ca2+ at very low Ka (0.3 µM with steep I/V slopes), a sensitivity to apamin, heteromeric assembly of the SKCa pore forming subunits with calmodulin (CaM), N rather than C terminal EF hand domain for Ca2+ binding, and Ca2+ gating near the K+ selectivity filter [58]. SKCa’s are unique in that calmodulin forms an integral part of the channel, forming its Ca2+-sensitive subunits [59]. In the presence of Ca2+, two calmodulin binding domains form a dimer, which allows the channel to open [12].

Antibodies against KCa2.2 and KCa2.3 were both used for immuno-staining and Western blot characterizations in purified mitochondria and in the enriched IMM fraction, respectively. We found that the identified protein was positive to both sets of antibodies. Because the sequence homology of the SKCa family of channels (KCa2.1, KCa2.2, KCa2.3) is highly conserved [60], the commercial antibodies we used might not have been selective enough to definitely identify the molecular identity of the specific mSKCa isoform. But we did confirm that the purified mSKCa protein formed a functional channel by recording channel activity after incorporating the protein into a planar lipid bilayer. The channel was inhibited by apamin, a blocker of plasmalemmal membrane SKCa channels. However, the recorded conductance states were higher than those reported for cell membrane SKCa channels, which are in the range of 10–14 pS [11, 58]. The underlying cause of this discrepancy is unclear. It is possible that mSKCa channels have biophysical attributes that are different from their cell membrane counterparts. In particular, the mSKCa channels exhibited multiple conducting states that appear to be Ca2+–dependent. As the [Ca2+] increased, the channel’s conductance also increased. Thus, at very low [Ca2+], lower conductances may be revealed that are closer to those reported for the plasmalemmal SKCa channel. In support of this, in some recordings we infrequently observed a conductance of 70 pS at 1 µM [Ca2+]. However, the mechanism that underlies this Ca2+–dependent gating of the mSKCa channel has yet to be delineated. Though it is premature to speculate on the structural homology between the mitochondrial and plasmalemmal SKCa channels, based on our MS data and the Ca2+ sensitivity of the mSKCa channel, the Ca2+calmodulin–binding domain and the S6 transmembrane region appear to be conserved. Indeed, the block of channel activity by apamin showed that this mSKCa channel does share a pharmacological property similar to the plasmalemmal SKCa.

However, the planar lipid bilayer experiments appear to indicate that the apamin binding site and the Ca2+ binding site are both localized to the same side of the mSKCa channel. This was an unexpected finding because apamin has been reported to be an external pore blocker that binds to the outer pore region of the plasmalemmal SKCa channel [61], whereas the Ca2+ sensing region was believed to be on the intracellular side, conferred by calmodulin that is constitutively bound to the C-terminus of the channel [12]. Consequently, our findings would imply that the position of the C-terminus in the mSKCa channel differs from that in the plasmalemmal SKCa channel. Therefore, based on the sidedness of the apamin effect and Ca2+ sensitivity, together with our observed biophysical properties, the mSKCa channel may exhibit some functional and structural differences from the plamalemmal SKCa channel. Additional experiments will be needed to confirm this possibility.

Our study represents the first conclusive report that identifies SKCa channels in cardiac myocyte mitochondria. Their presence in the IMM would indicate that they have an important function in fine-tuning regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics, perhaps via volume control, which is largely controlled by K+ flux. In contrast, the voltage and Ca2+-dependent BKCa channels may open only when ΔΨm is high (state 4 respiration) or in response to a large imbalance in m[Ca2+] or cytosolic [Ca2+], much as BKCa channels regulate cell membrane potential in excitable cells.

Three genes encode the SKCa family; all have been cloned, and the amino acid sequences predict subunits similar to those in other K+ channels. Channel specificity resides in the C terminal domains where each SKCa subtype interacts with the ubiquitous Ca2+ sensor CaM. This constitutive binding domain is called CaMBD [62]. Crystal structures show that SKCa+CaMBD contains two EF hand motifs within each of the globular N and C terminal regions separated by a flexible linker [62]. The C terminus is required to establish the link of SKCa and CaM. Substitution of neutral amino acids for aspartate and glutamate only in N terminus EF hand region blocks Ca2+ gating. This binding site is positioned just below the K+ selectivity filter, which suggests that conformational changes near or even in the selectivity filter itself function to gate SKCa channels. The 18 amino acid bee venom toxin apamin is highly selective for SK2 by docking at the pore entrance and between the S3–S4 loops [63].

SKCa channels in neurons lie adjacent to Ca2+ stores and Ca2+ channels. In nerve cells SKCa channels play a role in setting the intrinsic firing frequency, while BKCa channels regulate action potential shape and may contribute to the unique climbing fiber response [15]. The K+ flux mediated by BKCa and SKCa channels in mitochondria may be differentiated by both their sensitivities to Ca2+ and dependence on ΔΨm during states 3 and 4 respiration. Because there are many differences between these channels, the functional effects of opening these channel are expected to differ; e.g., unlike BKCa, SKCa channel opening may “fine tune” matrix K+ influx due to changing Ca2+ levels independent of changes in ΔΨm during the variable rate of oxidative phosphorylation.

4.2. mSKCa channel opening triggers preconditioning via ROS

The presence of both SKCa and BKCa channels in cardiac myocyte IMM indicates a functional importance for these channels during excess mCa2+ loading; moreover their endogenous opening during IPC, or as a pharmacological therapy, may be an important trigger for cardioprotection. It is unclear if these drugs actually open these K+ channels directly to elicit preconditioning, or if they themselves alter mitochondrial bioenergetics (as mild uncouplers of oxidative phosphorylation), which mediates the memory of preconditioning by other downstream effectors. Although the mitochondrial preconditioning effect of DCEB appears to require both mSKCa channel opening and generation of O2•−, these factors are not effectors of PPC as the DCEB and TBAP are washed out before ischemia.

There is ample evidence that O2•− is necessary to trigger PPC by mK+ channel openers but the mechanism of O2•−, and its products or reactants, in mediating PPC is unknown. An increase in redox state (increased NADH, decreased FAD) at a given [O2] can result in increased O2•− generation [64]. O2 derived free radical “bursts” are known to occur during reperfusion when excess O2 is available. Our group [4, 26, 27, 33] and others [35, 65] have shown, moreover, that ROS are also formed in excess during ischemia before reperfusion when tissue O2 tension decreases, the redox state increases and then decreases, and cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) activity is low [66]. The putative mKATP channel opener diazoxide [67] mimicked IPC on reducing infarct size and the ROS scavengers, N-acetylcysteine [68] or N-mercapto-propionyl-glycine [24], blocked the preconditioning effect of diazoxide. It has been suggested that mKATP channel opening can cause a small increase in ROS formation [69], which may trigger cardioprotection through activation of protein kinases. Conversely, ROS have also been proposed to activate the sarcolemmal KATP channel by modulating its ATP binding sites as this effect is blocked by GLIB or by ROS scavengers [70]. Others have proffered that ROS produced during IPC may afford cardioprotection on reperfusion directly, or via a feed forward mechanism for KATP channel-induced ROS production [71, 72].

In the present study evidence that the protective effect of DCEB is mediated by ROS is indicated by reversal of the protection in the presence of TBAP. O2•− or OH•, or even non-radical reactants like H2O2 or ONOO− (formed in the absence or presence of NO•, respectively) may actually produce the preconditioning responses, but O2•− appears necessary to initiate the response. It is also possible that mSKCa, mBKCa, and or mKATP channel activation is altered by ROS as a feed forward controller of mitochondrial function. Enhanced electron transfer before ischemia may minimize respiratory inefficiency, i.e., reduced matrix contraction and improved respiration on reperfusion. mSKCa channel opening, like mKATP channel opening, and indeed opening of any mK+ channel, could induce PPC by mildly enhancing O2•− generation, which stimulates enzymatic pathways that help to protect the cell from IR injury. Interestingly, we observed that O2•− dismutation by TBAP blocked protection by DCEB.

When DCEB was given alone or with any of the inhibitors, it had no direct detectable effect on mechanical function or mitochondrial bioenergetics (redox state, O2•− levels) in isolated hearts. In our related study [4] neither NS1619 nor its antagonist PAX showed any direct effect on measured variables. In the ex vivo, intact heart perfused with adequate substrates and O2, mitochondria are mostly respiring in the non-resting state 3, so small changes in O2•− between states 3 (ample ADP) and 4 (consumed ADP) respiration can not be observed. However, in isolated cardiac mitochondria we reported that low, but not high, concentrations of the BKCa channel opener NS1619 can increase resting state 4 respiration and ROS generation while maintaining IMM potential (ΔΨm) [6].

We propose similarly that DCEB, like NS1619, increases intramatrix K+, which is replaced immediately with H+ via KHE. We suggest that at low concentrations of these openers a transient increase in matrix acidity, i.e., via a proton leak, stimulates respiration but maintains ΔΨm so that a greater amount of O2•− is generated at mitochondrial respiratory complexes due to impaired electron transport. O2•− itself, or a reactant, may in turn stimulate downstream-induced phosphorylation pathways fostering K+ channel opening as necessary when ischemia occurs. The net effect could be preservation of mitochondrial bioenergetics during ischemia as evidenced by better maintenance of the reduced state (high NADH and low FAD) and smaller increases in O2•− generation and less m[Ca2+] overload. This could lead to better preservation of oxidative phosphorylation and ATP turnover leading to better utilization of ATP on initial reperfusion after ischemia.

4.3. Putative mechanism of mitochondrial K+ flux on mitochondrial protection during IR injury

BKCa and SKCa channel openers appear to have a profound ability to induce PPC but the mechanism is unclear. It is possible that brief ischemia as in IPC causes a slight elevation of mCa2+ that induces mSKCa and mBKCa channel opening and, like mKATP channel opening, leads to partial dissipation of ΔΨm and or matrix swelling as a protective mechanism against subsequent IR injury. It is now clear that K+ is required for optimal functioning of oxidative phosphorylation because matrix K+ flux largely regulates matrix volume and can modulate ΔΨm [73–75]. Trans-matrix K+ flux can also modulate ROS production [6]. mSKCa channels, like mBKCa channels [57, 76], may act to modulate matrix volume during times of increased matrix Ca2+ load, such as occurs during IR injury [25, 29]. Xu et al. [57] first suggested that opening mBKCa channels to enhance matrix K+ influx is an important factor in mitigating IR injury in a manner similar to mKATP channels. They proposed [57] that the function of mBKCa channels was to improve the efficiency of mitochondrial energy production.

As with the other two K+ channels reported in mitochondria, KATP and BKCa, once the K+ channel is opened the increase in K+ uptake leads to changes in the matrix as described by Garlid et al. and Beavis et al. [77, 78]. Electrogenic H+ efflux driven by the respiratory chain is balanced by electrophoretic K+ influx. If this were uncompensated, it would cause a very large increase in matrix pH of about 2 pH units. Partial compensation is provided by electroneutral uptake of substrate anions, such as phosphate. The compensation is partial because the concentration of phosphate in the cytosol is much lower than that of K+, and this imbalance leads to matrix alkalinization [79, 80]. Matrix alkalinization now releases the K+/H+ antiporter from inhibition by matrix protons [75], causing K+ efflux to increase in response to increased K+ uptake until a new K+ steady state is achieved. An increase in futile K+ cycling is believed to produce mild uncoupling [78] and regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics and ROS emission.

Although mKCa channels likely play a role in regulating mitochondrial bioenergetics, it is unknown how opening of these channels leads to more normalized NADH/FAD levels, reduces excess ROS, and decreases Ca2+ loading during IR. Just as the existence and function of the mKCa channel in IMM on mitochondrial respiration is unclear, so is the mechanism of K+ influx via mKATP channels in IMM [73, 76, 81–84]. For the KATP channel it was proposed that its opening depolarizes the IMM to cause uncoupling and hasten respiration [76, 81, 85]. Subsequent ischemia would then reduce the driving force for Ca2+ influx through the mCa2+ uniporter; this could attenuate mCa2+ overload [86, 87] so that energized mitochondria on reperfusion would perform more efficiently. Indeed the putative mKATP channel opener diazoxide is reported to reduce the rate of mCa2+ uptake by depolarizing the IMM and decreasing the driving force for mCa2+ entry [76, 81, 85], although this could be due to respiratory inhibition distinct from KATP channel opening [73, 88].

Garlid’s group [73, 88], however, proposed that the physiological role of potential mK+ channels is control of matrix volume rather than dissipation of ΔΨm and uncoupling. They postulated that matrix swelling by K+ uptake is caused by concomitant uptake of Cl− and water by osmosis. But subsequent activation of mKHE may only slightly dissipate the proton gradient (ΔµH) by increasing matrix acidity (proton leak) without significantly altering ΔΨm [74, 88]. In turn, mitochondrial swelling might optimize mitochondrial function because partial uncoupling was seen to improve efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation [89]. More specifically, during hypoxia matrix K+ influx appears to maintain a normal matrix volume, which preserves a narrow intermembrane space and helps to facilitate energy transfer to ATP-utilizing sites, to reduce outer membrane permeability to nucleotides, and to slow ATP hydrolysis [73–75]. The end result of mSKCa channel opening, like mKCa channel opening, may be to improve mitochondrial efficiency, reduce m[Ca2+] and ROS production, and thereby to protect overall mitochondrial function during IR.

4.4. Interrelationship and timing of mCa2+ loading, ΔΨm, redox state, and ROS during cardiac IR injury

Prolonged mitochondrial ischemia is marked by the following: decreasing ΔΨm, an oxidized redox state, excess ROS, matrix contraction, and increasing mCa2+ loading. Ca2+ overload due to leaky IMM could impede normal electron transfer so that greater amounts of ROS are produced during IR. Alternatively, ROS can damage membranes by lipid peroxidation; this can hamper selective permeability to ions and allow cytosolic and mCa2+ uptake as a result of increased reverse mode sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchange (NCE) [90, 91].

Our studies in the intact heart model show an interrelationship between O2•− produced, redox state, and mCa2+ influx during ischemia. Continuously measured NADH and O2•− changed together during ischemia as well as during reperfusion. Ischemia-induced rises in NADH [4, 25, 28, 30, 33], ROS [4, 26, 27, 33], and m[Ca2+] [4, 25, 29, 33] returned closer to normal values on reperfusion after PPC. These effects were reversed by ROS scavengers or by blocking sarcolemmal KATP and/or mKATP channel opening with GLIB or 5-hydroxydecanoate [27, 29]. Preconditioning also led to reduced ROS generation and improved ATP synthesis in isolated mitochondria [92]. These studies suggest that temporary exposure to distinct cardioprotective drugs before ischemia causes ROS-dependent changes in mitochondrial bioenergetics that initiates a preconditioning effect. mKCa is likely to be activated endogenously as matrix Ca2+ rises in response to an increase in Ca2+ load, such as occurs during ischemia; opening these channels pharmacologically before ischemia may lead to added protection.

4.5 Summary and limitations

We have furnished ample evidence for the presence of SKCa channels in purified mitochondria and in IMM from cardiac cells, for the functional effects of the IKCa and SKCa channel opener DCEB on K+ flux in isolated mitochondria, and for the channel conductance of SKCa proteins incorporated into planar lipid bilayers. Moreover, we have demonstrated that SKCa channel opener DCEB initiates cardiac PPC as shown by marked metabolic and functional improvements during reperfusion. These are supported by better preserved reduced redox state (high NADH and low FAD), decreased O2•− production, reduced mCa2+ loading during IR, and reduced infarct size. The protection by DCEB was blocked by dismutation of O2•− with TBAP and by the SKCa antagonist NS8593. It is possible that mSKCa channel opening induces a mild proton leak due to mKHE, which accelerates respiration, but maintains ΔΨm, so that small amounts of generated O2•− triggers a downstream protective pathway.

All of the K+ channel agonists may converge on a pathway that stimulates a small amount of ROS. That TBAP blocks protection by this drug and that mitochondria are a major source of ROS, suggest that DCEB exerts its effects primarily in mitochondria. Only relative changes in NADH and FAD levels and ROS formation can be assessed in our model. We did not test if the mSKCa channel is open during IR injury, although we have preliminary evidence that the BKCa channel is open during reperfusion [93]. It is plausible that some factors that induce preconditioning, like small increases in ROS or m[Ca2+], are the same factors, albeit at much greater levels, that cause IR damage. Thus the individual stages of triggering, activation and end-effect must be well delineated to unravel the complicated mechanism underlying the cardiac protection afforded by preconditioning.

Highlights.

We identify small Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels in guinea pig cardiac mitochondria.

Identity based on Westerns, confocal microscopy, immune-gold EM, and MS.

Function based on K+ flux, Ca2+, apamin, and UCL1684–sensitive conductance.

Channel agonist, DCEBIO protects hearts against IR injury, and antagonist NS8593 blocks protection.

Mechanism of protection in isolated hearts is mediated by the superoxide radical.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anita Tredeau, Clive Wells, and Glen R. Slocum for their valuable contributions to this research study, which was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL089514 to DFS and R01 HL095122 to AKSC and RK Dash), the American Heart Association (0355608Z and 0855940G to DFS), and the Veterans Administration (8204-05P to DFS).

Abbreviations

- IR

ischemia reperfusion

- SKCa

small conductance Ca2+ -sensitive K+ channel

- BKCa

big conductance Ca2+ -sensitive K+ channel

- KATP

ATP -sensitive K+ channel

- DCEB

5,6-dichloro-1-ethyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzimidazol-2-one

- IMM

inner mitochondrial membrane

- TBAP

Mn(III) tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin

- PPC

pharmacological preconditioning

- TRAM

TRAM-34: 1-[(2-chlorophenyl) (diphenyl)methyl]-1H-pyrazole

- GLIB

glibenclamide

- PAX

paxilline

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- IEM

immune-electron microscopy

- MS

mass spectroscopy

- NS8593

N-[(1R)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-naphthalenyl]-1H-benzimidazol-2-amine hydrochloride

- UCL 1684

6,10-diaza-3(1,3)8,(1,4)-dibenzena-1,5(1,4)-diquinolinacy clodecaphane

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose about any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Stowe DF, Camara AK. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in excitable cells: modulators of mitochondrial and cell function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1373–1414. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camara AK, Lesnefsky EJ, Stowe DF. Potential therapeutic benefits of strategies directed to mitochondria. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:279–347. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camara AK, Bienengraeber M, Stowe DF. Mitochondrial approaches to protect against cardiac ischemia and reperfusion injury. Front Physiol. 2011;2:1–34. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stowe DF, Aldakkak M, Camara AK, Riess ML, Heinen A, Varadarajan SG, Jiang MT. Cardiac mitochondrial preconditioning by Big Ca2+-sensitive K+ channel opening requires superoxide radical generation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H434–H440. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00763.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinen A, Aldakkak M, Stowe DF, Rhodes SS, Riess ML, Varadarajan SG, Camara AK. Reverse electron flow-induced ROS production is attenuated by activation of mitochondrial Ca2+ -sensitive K+ channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1400–H1407. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00198.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinen A, Camara AK, Aldakkak M, Rhodes SS, Riess ML, Stowe DF. Mitochondrial Ca2+-induced K+ influx increases respiration and enhances ROS production while maintaining membrane potential. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C148–C156. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00215.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh S, Syme CA, Singh AK, Devor DC, Bridges RJ. Benzimidazolone activators of chloride secretion: potential therapeutics for cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:600–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Syme CA, Gerlach AC, Singh AK, Devor DC. Pharmacological activation of cloned intermediate- and small- conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C570–C581. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wulff H, Miller MJ, Haensel W, Grissmer S, Cahalan MD, Chandy KG. Design of a potent and selective inhibitor of the intermediate -conductance Ca2+ -activated K+ channel, IKCa1: A potential immunosupressant. PNAS. 2000;97:8151–8156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stocker M. Ca2+-activated K+ channels: molecular determinants and function of the SK family. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:758–770. doi: 10.1038/nrn1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hille B. Ion channels in excitable membranes. Third ed. Sunderland: Sinauer Asociates, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schumacher MA, Rivard AF, Bachinger HP, Adelman JP. Structure of the gating domain of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel complexed with Ca2+/calmodulin. Nature. 2001;410:1120–1124. doi: 10.1038/35074145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruening-Wright A, Schumacher MA, Adelman JP, Maylie J. Localization of the activation gate for small conductance Ca2+- activated K+ channels. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6499–6506. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06499.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor MS, Bonev AD, Gross TP, Eckman DM, Brayden JE, Bond CT, Adelman JP, Nelson MT. Altered expression of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK3) channels modulates arterial tone and blood pressure. Circ Res. 2003;93:124–131. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000081980.63146.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y, Tuteja D, Zhang Z, Xu D, Zhang Y, Rodriguez J, Nie L, Tuxson HR, Young JN, Glatter KA, Vazquez AE, Yamoah EN, Chiamvimonvat N. Molecular identification and functional roles of a Ca2+ -activated K+ channel in human and mouse hearts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49085–49094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weatherall KL, Seutin V, Liegeois JF, Marrion NV. Crucial role of a shared extracellular loop in apamin sensitivity and maintenance of pore shape of small-conductance calcium-activated potassium (SK) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18494–18499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110724108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheng JZ, Ella S, Davis MJ, Hill MA, Braun AP. Openers of SKCa and IKCa channels enhance agonist-evoked endothelial nitric oxide synthesis and arteriolar vasodilation. FASEB J. 2009;23:1138–1145. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-120451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strobaek D, Teuber L, Jorgensen TD, Ahring PK, Kjaer K, Hansen RS, Olesen SP, Christophersen P, Skaaning-Jensen B. Activation of human IK and SK Ca2+ -activated K+ channels by NS309 (6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2,3-dione 3-oxime) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1665:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedarzani P, McCutcheon JE, Rogge G, Jensen BS, Christophersen P, Hougaard C, Strobaek D, Stocker M. Specific enhancement of SK channel activity selectively potentiates the afterhyperpolarizing current I(AHP) and modulates the firing properties of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41404–41411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wulff H, Kolski-Andreaco A, Sankaranarayanan A, Sabatier JM, Shakkottai V. Modulators of small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels and their therapeutic indications. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1437–1457. doi: 10.2174/092986707780831186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedarzani P, Stocker M. Molecular and cellular basis of small--and intermediate-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channel function in the brain. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3196–3217. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8216-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkins DP, Strobaek D, Hougaard C, Jensen ML, Hummel R, Sorensen US, Christophersen P, Wulff H. Negative gating modulation by (R)-N-(benzimidazol-2-yl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-naphthylamine (NS8593) depends on residues in the inner pore vestibule: pharmacological evidence of deep-pore gating of KCa2 channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:899–909. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.069807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diness JG, Sorensen US, Nissen JD, Al-Shahib B, Jespersen T, Grunnet M, Hansen RS. Inhibition of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels terminates and protects against atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:380–390. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.957407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pain T, Yang XM, Critz SD, Yue Y, Nakano A, Liu GS, Heusch G, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Opening of mitochondrial KATP channels triggers the preconditioned state by generating free radicals. Circulation Research. 2000;87:460–466. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.6.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varadarajan SG, An JZ, Novalija E, Smart SC, Stowe DF. Changes in [Na+]i, compartmental [Ca2+], and NADH with dysfunction after global ischemia in intact hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H280–H293. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.1.H280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kevin L, Camara AKS, Riess MR, Novalija E, Stowe DF. Ischemic preconditioning alters real-time measure of O2 radicals in intact hearts with ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H566–H574. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00711.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kevin L, Novalija E, Riess MR, Camara AKS, Rhodes SS, Stowe DF. Sevoflurane exposure generates superoxide but leads to decreased superoxide during ischemia and reperfusion in isolated hearts. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:945–959. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000052515.25465.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riess ML, Camara AKS, Chen Q, Novalija E, Rhodes SS, Stowe DF. Altered NADH and improved function by anesthetic and ischemic preconditioning in guinea pig intact hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H53–H60. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01057.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riess ML, Camara AK, Novalija E, Chen Q, Rhodes SS, Stowe DF. Anesthetic preconditioning attenuates mitochondrial Ca2+ overload during ischemia in guinea pig intact hearts: reversal by 5- hydroxydecanoic. Acid, Anesth Analg. 2002;95:1540–1546. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200212000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.An JZ, Camara AK, Rhodes SS, Riess ML, Stowe DF. Warm ischemic preconditioning improves mitochondrial redox balance during and after mild hypothermic ischemia in guinea pig isolated hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2620–H2627. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01124.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camara AK, Riess ML, Kevin LG, Novalija E, Stowe DF. Hypothermia augments reactive oxygen species detected in the guinea pig isolated perfused heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1289–H1299. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00811.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.An JZ, Camara AK, Riess ML, Rhodes SS, Varadarajan SG, Stowe DF. Improved mitochondrial bioenergetics by anesthetic preconditioning during and after 2 hours of 27*C ischemia in isolated hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;46:280–287. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000175238.18702.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riess ML, Camara AK, Kevin LG, An J, Stowe DF. Reduced reactive O2 species formation and preserved mitochondrial NADH and [Ca2+] levels during short-term 17 °C ischemia in intact hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:580–590. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]