Abstract

Deposition of amyloid β (Aβ) containing plaques in the brain is one of the neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease (AD). It has been suggested that modulation of neuronal activity may alter Aβ production in the brain. We postulate that these changes in Aβ production are due to changes in the rate-limiting step of Aβ generation, APP cleavage by γ-secretase. By combining biochemical approaches with Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy, we found that neuronal inhibition decreases endogenous APP and PS1 interactions, which correlates with reduced Aβ production. By contrast, neuronal activation had a two-phase effect: it initially enhanced APP-PS1 interaction leading to increased Aβ production, which followed by a decrease in the APP and PS1 proximity/interaction. Accordingly, treatment of neurons with naturally secreted Aβ isolated from AD brain or with synthetic Aβ resulted in reduced APP and PS1 proximity. Moreover, applying low concentration of Aβ42 to cultured neurons inhibited de novo Aβ synthesis. These data provide evidence that neuronal activity regulates endogenous APP-PS1 interactions, and suggest a model of a product-enzyme negative feedback. Thus, under normal physiological conditions Aβ may impact its own production by modifying γ-secretase cleavage of APP. Disruption of this negative modulation may cause Aβ overproduction leading to neurotoxicity.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Presenilin 1, amyloid β precursor protein, FLIM (Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy), neuronal activity

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurological disorder of the elderly that is associated with synaptic loss and displays amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles as characteristic pathological hallmarks. The main components of amyloid plaques are Aβ peptides of different lengths generated from the amyloid β precursor protein (APP) by β-secretase and PS1/γ-secretase.

Recent study linked regional differences in neuronal activity and cerebral metabolism with amyloid deposition in the brain of transgenic mice (Bero et al., 2011); however, the underlying mechanism remains unclear. It has been suggested that neuronal activity may control APP processing, but reports in the literature how Aβ production is affected provide conflicting results. Studies using slice cultures and cultured cortical neurons show a positive correlation of Aβ secretion with neuronal activity, and suggest that neuronal activation favors cleavage of APP by β-secretase over α-secretase (Hoe et al., 2009; Lesne et al., 2005; Kamenetz et al., 2003). By contrast, other studies report that stimulation of NMDA receptors in primary cultured neurons inhibits Aβ release, induces trafficking of α-secretase ADAM10 to the postsynaptic membrane, and increases α-secretase mediated APP cleavage within the Aβ region (Marcello et al., 2007). The role PS1/γ-secretase plays in activity-controlled Aβ generation, however, remains poorly understood. Moreover, although the role of Aβ in Alzheimer's disease pathology is well established, it remains unclear whether Aβ at low, physiological concentrations may have a function in the brain.

Thus, the goal of the present study is to elucidate how neuronal activity affects endogenous Aβ production, to determine if APP and PS1/γ-secretases interaction is involved, and to evaluate whether Aβ may play a regulatory role in its own production. Using biochemical and morphological methods, we found that neuronal activation increases while neuronal inhibition decreases Aβ production and APP-PS1 proximity in primary neurons. Moreover, we show changes in APP-PS1 interactions over time, and report a novel observation that elevated Aβ generated after initial neuronal activation has a negative feedback effect on APP-PS1 interactions, diminishing further Aβ generation. This suggests that at physiological concentrations Aβ may play a negative autoregulatory role in the normal brain.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and transfection

Rabbit anti-APP C-terminus (APP CT, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to PS1 loop domain (Millipore, Temecula, CA) were used to assess APP-PS1 proximity by FLIM. Aβ specific mAbs 82E1 (IBL, Fujioka, Japan), 6E10 (Covance, Princeton, NJ) and mAb to Actin (AC-40, Sigma-Aldrich) were used for immunoblotting. Rabbit anti-GAD65, anti-GluR2 mAb (both from Millipore, Temecula, CA) and chicken anti-MAP2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) were used to assess GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in culture. Rabbit polyclonal R1282 antibody used for Aβ immunoprecipitation was a gift from Dr. Dennis Selkoe (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston). The capture antibody (BNT77, against Aβ11-28) and the detection antibodies (BA27 for Aβ40 and BC05 for Aβ42) used for Aβ-ELISA were from Takeda (Osaka, Japan). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated or Cy3-conjugated species-specific anti-IgG secondary antibodies used for immuno-detection were from Molecular Probe (Eugene, OR) and Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA), respectively. The carboxyl-terminal GFP-tagged truncated APP construct, APP C99-GFP, was generated as previously described (Kinoshita et al., 2002). Transfection of this plasmid into primary neurons was performed using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Primary neuronal cultures

Mixed cortical and hippocampal primary neurons were generated from embryonic day 15-16 CD1 wild type or Tg2576 mice overexpressing 695 amino acids isoform of human APP containing K670N and M671L Swedish mutations, as previously described (Berezovska et al., 1999; Wu et al., 2010). Briefly, the cells re-suspended in chemically defined Neurobasal Media (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum were plated on poly-D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) coated dishes. Twenty-four hours after the plating, the cell culture media was exchanged to Neurobasal Media containing 2% B27 supplement (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD), and neurons were maintained for 11-14 days in vitro (DIV) prior to treatment with inhibitory or excitatory agents, or with Aβ (see sections below).

Pharmacological treatment

To modulate neuronal activity in 11-14 DIV primary neurons we adopted the protocol described by Kamenetz et al (2003) using 10mM MgCl2 (N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blocker), 1μM Tetrodotoxin (sodium channel blocker), 100μM Picrotoxin (non competitive antagonist for GABAA receptor chloride channel) (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or H2O (vehicle control). The cells were treated for various periods of time (see Results), ranging from 6 to 24 hours. Neuronal viability and potential toxicity due to the treatment was assessed by visual inspection of neuronal morphology, by CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega, Madison, WI), or by monitoring the release of Adenylate Kinase in the culture medium using the ToxiLight Bio Assay kit (Cambrex, Rockland, ME). After 6 to 24 hours of treatment, conditioned media was collected for Aβ-ELISA, and cells were immunostained prior to FLIM experiments.

Aβ treatment

Synthetic Aβ42, Aβ40 and reversed Aβ40-1 peptides (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA) were prepared as 10μM stock solution, stored at -20°C and reconstituted in neuronal culture medium to 1nM concentration immediately prior to neuronal treatment. Low oligomeric Aβ42 was prepared by applying 100μl of 1mg/ml synthetic Aβ42 peptide to size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on Superdex75 10/300 GL column (GE healthcare), and eluting in 10mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) with AKTA purifier 10 (GE healthcare) at a flow rate of 0.5ml/min. The presence of Aβ oligomers in the selected eluted fractions was confirmed by western blotting. Protein concentration was measured by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and 1nM low order oligomeric Aβ42 fraction B2 was used for pulse-chase experiments (Supplementary Fig. 4). Alternatively, neurons were treated with naturally generated Aβ extracted from brains of an AD patient or an age matched control individual. Briefly, cortical gray matter of temporal lobe from AD or non-demented control brain was homogenized in 4 volumes of Tris-buffer saline solution (TBS) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) with 25 strokes on a mechanical Dounce homogenizer and centrifuged at 260,000x g for 20 minutes at 4°C. 75μl of TBS soluble fractions of AD brain or control brain were applied to SEC Superdex75 10/300 GL column in 50mM ammonium acetate (pH 8.5) with AKTA purifier 10, and eluted at a flow rate of 0.5ml/min (Townsend et al., 2006). The presence of Aβ in the eluted fractions was confirmed by western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 4). Aβ-containing fractions (11-17KD) were dialyzed against PBS overnight at 4°C, and mixed with culture medium at a 1:1 ratio to treat primary neurons for 1 hour.

Immunocytochemistry

After pharmacological or Aβ treatment, cells were washed briefly in PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes. After three washing steps with PBS, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X 100 for 20 minutes and incubated in 1.5% normal donkey serum (NDS) blocking solution for 45 minutes. Primary antibodies mAb PS1 loop and rabbit anti-APP CT diluted in 1.5% NDS were applied overnight at 4°C, whereas corresponding Alexa 488- and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies were applied at room temperature for one hour. Before and after antibody application, cells were washed three times in PBS for ten minutes each to minimize nonspecific staining. After immunostaining, cells were covered with glass coverslips using GVA mounting solution (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA) and were used for the FLIM assay to evaluate endogenous PS1 and APP interactions. Alternatively, to distinguish between the PS1 interaction with either full length APP or APP C-terminal fragments, the primary neurons were transfected with C99-GFP (FRET donor) for 24 hours prior to the treatment (see above). Treated cells were fixed and immunostained with mAb PS1 loop followed by Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (FRET acceptor). BACE-CT or ADAM-10 CT antibodies (both from Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) were used to detect β- and α-secretases, respectively. The primary neuronal cultures were immunostained with GAD65 or GluR2 antibodies to determine the percentage of GABAergic or glutamatergic neurons, respectively. MAP2 was used as a neuronal marker (total number of neurons); GFAP and Iba antibodies were used to label astrocytes and microglia, respectively.

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM)

The proximity between fluorophore labeled endogenous PS1 and APP was assessed by previously validated FLIM assay as described (Berezovska et al., 2003; Lleo et al., 2004). Briefly, the baseline lifetime (t1) of the Alexa 488 fluorophore (negative control, FRET absent) was measured in the absence of an acceptor fluorophore. Upon excitation of the donor fluorophore in the presence of Cy3 acceptor fluorophore, some of the donor emission energy is non-radiatively transferred to the acceptor if the donor and acceptor are less than 5-10 nm apart (FRET present). This results in a characteristic shortening of the donor fluorophore lifetime (t2). The degree of donor fluorophore lifetime shortening (FRET efficiency) correlates with the change in proximity between the APP and PS1 molecules: high FRET efficiency indicates close APP and PS1 proximity. The percent FRET efficiency is calculated using the following equation: EFRET=100*(t1-t2)/t1 (Uemura et al., 2010). In case of the C99-GFP transfection, the GFP fluorophore was used as the donor.

A multiphoton microscope (Radiance 2000, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with a femtosecond mode-locked Ti:Sapphire Laser (Mai Tai; Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, CA) 2-photon excitation at 800 nm, a high-speed photomultiplier tube (MCP R3809; Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan), and a time correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) acquisition board (SPC 830; Becker&Hickl, Berlin, Germany) were employed for the lifetime imaging as previously described (Berezovska et al., 2003, 2005; Lleo et al., 2004). SPCImage software (Becker&Hickl, Berlin, Germany) was used to determine the donor fluorophore lifetimes by fitting the data to one (negative control) or two (acceptor present) exponential decay curves.

Western blotting of cell lysates

After 6 or 24 hours of treatment, primary neurons were lysed in 1% CHAPSO lysis buffer (150mM NaCl, 20mM Tris, 1mM EDTA and protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.4). The cell lysates were electrophorized on 4-20% Tris-Glycine polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, CA), incubated with corresponding primary and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, and detected with SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The respective protein bands were quantified using ImageJ software.

Pulse-chase and immunoprecipitation experiment

14 DIV primary neurons from Tg2576 mice were incubated with methionine-free culture medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) for 2 hours at 37°C, followed by pulse-labeling with 100μCi/ml [35S]methionine for 1 hour. Neurons were washed with PBS twice and chased with Neurobasal media containing 2mM Methionine in the presence of 1nM synthetic Aβ42 peptide, 1nM low oligomeric Aβ42 eluted from SEC, or 1nM reversed Aβ40-1 peptide as a control. Medium was collected at 0, 30, 60 and 90 minutes after the pulse. The medium was incubated with a mixture of R1282 and 6E10 antibodies coupled protein A and G sepharose beads (GEHealthcare Life. Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) overnight at 4°C. To compensate for the interference of exogenous Aβ with the efficiency of endogenous Aβ immunoprecipitation, 1nM Aβ42 or Aβ40-1 was added to the medium collected from cells pulse-chased in the presence of Aβ40-1 and Aβ42, respectively. After washing, the SDS-buffer eluted samples were resolved on 10-20% Tris-glycine gel and detected by PhosphoImager.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using StatView for Windows, Version 5.0.1 (SAS Institute, Inc.). For quantitative Western blot or gel autoradiography analysis, the intensities of protein bands from 4 to 8 independent experiments were measured by Image J. Levels of full length APP and PS1 CTF were normalized to the corresponding actin bands, while APP CTFs were normalized to full length APP. [35S] labeled Aβ bands at different time points were normalized to chase time 0 in each treatment condition. The difference between two samples or between two time points was determined using t-test, and was considered significant at p<0.05.

Results

Neuronal inhibition reduces Aβ production and decreases APP-PS1 interactions

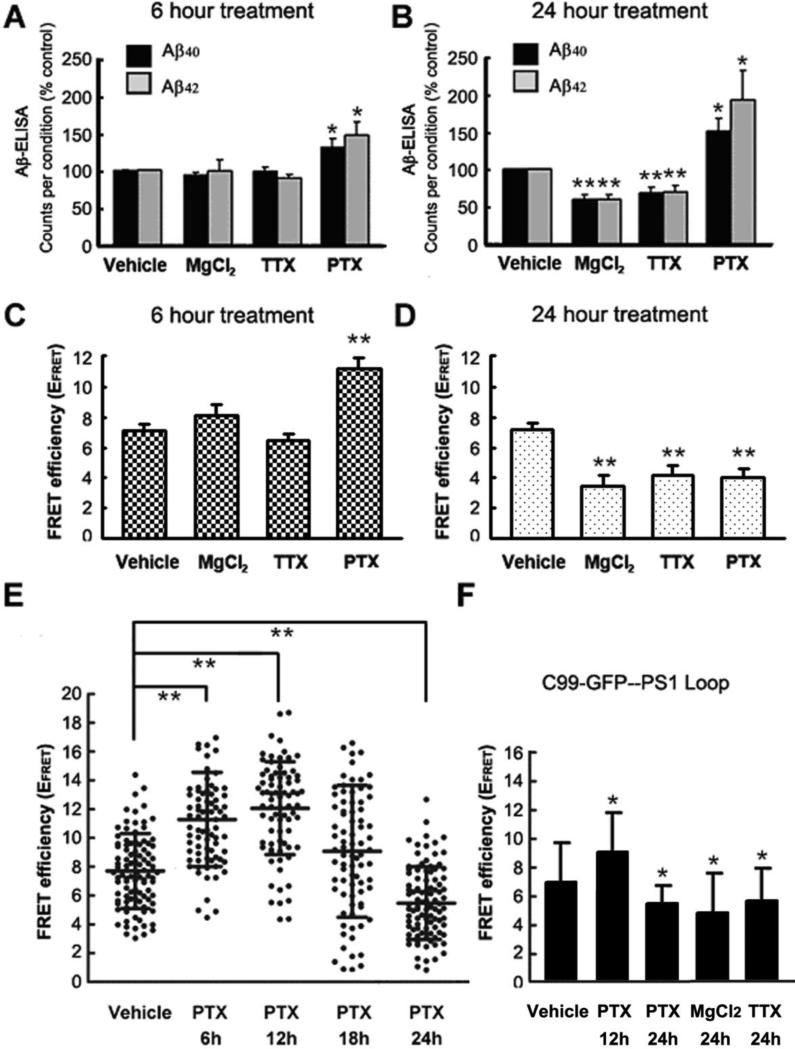

To determine whether inhibition of neuronal activity affect endogenous Aβ secretion, we subjected 11-14DIV primary neurons prepared from wild type mouse embryos to treatment with 10mM MgCl2, 1μM Tetrodotoxin (TTX), or H2O vehicle as a control. As detected by ELISA measurements, the total endogenous mouse Aβ in the conditioned media of vehicle treated neurons was 94.1±3.5 pM for Aβ40 and 17.7±0.5 pM for Aβ42 after 6 hours and 239.1±18.5 pM for Aβ40 and 36.8±2.6 pM for Aβ42 after 24 hours. As shown in Figure 1A and B, we did not detect significant change in Aβ production after 6 hours of neuronal inhibition with MgCl2 or TTX, compared to the vehicle treated control neurons. 24 hours of neuronal inhibition, however, resulted in significantly decreased levels of both Aβ40 and Aβ42, compared to control.

Figure 1.

Modulation of neuronal activity affects endogenous Aβ production and spatial alignment of the APP and PS1 in primary neurons. 11-14 DIV wild type primary neurons were treated with vehicle, 10mM MgCl2, 1μM TTX or 100μM PTX for 6 hours (A) or 24 hours (B), and conditioned media was collected for ELISA measurements. The amount of each Aβ species was normalized to that in conditioned media of vehicle-treated control cells. n=6 independent experiments, each treatment was performed in triplicates for each experiment. FLIM assay was performed to access the APP-PS1 proximity in primary neurons treated with vehicle, MgCl2, TTX or PTX for 6 hours (C) or 24 hours (D). FRET efficiency is presented as mean ± SEM. (E) Scatter plot of FRET efficiencies reflecting PS1 to APP proximity in neurons treated with vehicle or PTX for 6 hours, 12 hours, 18 hours and 24 hours. (F) FRET efficiency in neurons transfected with C99-GFP and treated with vehicle, PTX for 12 or 24 hours, and MgCl2 or TTX for 24 hours. Percent FRET efficiency was calculated using C99-GFP lifetime in the absence and presence of Cy3-PS1 CTF, and is presented as mean ± SD. n=3 independent experiments for C-F FLIM experiments. * p<0.05, **p<0.001 versus vehicle-treated controls, one way ANOVA.

To test whether the observed changes in Aβ production after inhibition of neuronal activity are caused by altered interaction between the APP substrate and PS1/γ-secretase, we employed our previously described FRET-based assay, FLIM (Berezovska et al., 2005; Lleo et al., 2004). Primary neurons treated with MgCl2 or TTX were subsequently immunostained to label an epitope on the PS1 TM6-7 loop with Alexa 488 donor fluorophore, and an epitope on the APP C-terminus with a Cy3 acceptor fluorophore. Thus, measuring Alexa 488 donor fluorophore lifetime in the FLIM assay assessed the proximity of the PS1 loop region, which is near the γ-secretase active site, to the C-terminus of APP. As expected, in the presence of Cy3 acceptor on the APP CT the donor fluorophore lifetime in the vehicle treated cells significantly shortens, compared to that in the no-acceptor negative control, indicating close proximity between the PS1 loop and APP CT. The estimated FRET efficiency (EFRET) in vehicle treated cells was ~7.07 ± 0.47 % (Fig. 1C and D). Six hours of neuronal inhibition with MgCl2 or TTX did not change the EFRET significantly (Fig. 1C). However, after 24 hours of the treatment we observed significant decrease in the EFRET compared to that in the vehicle treated control (Fig. 1D). This indicates that 24 hours of neuronal inhibition significantly decreases proximity, and thus interactions between PS1/γ-secretase and APP substrate. We did not detect statistically significant effect of 24-hour neuronal inhibition (TTX) on APP interactions with BACE or ADAM10 (Supplemental Fig. 1)

Effect of neuronal stimulation on Aβ production and APP-PS1 interactions

Neuronal stimulation with 100μM Picrotoxin (PTX) resulted in considerable accumulation of secreted Aβ in the condition medium after 6 hours (~150pM) and 24 hours (~400pM), as compared to that in neurons treated with H2O vehicle (Fig. 1A and B). Consistent with this finding, the EFRET was significantly higher in the 6 hours PTX treated neurons, compared to that in the vehicle treated cells (Fig. 1C), suggesting increased proximity between the APP and PS1/γ-secretase. Surprisingly, we found that the EFRET was significantly decreased in neurons stimulated with PTX for 24 hours (Fig. 1D), suggesting that at this time APP-PS1 interaction was diminished.

To further investigate the discrepancy between elevated Aβ production and decreased APP-PS1 interaction after 24 hours of neuronal activation, we monitored the proximity between APP and PS1 in more details after 6 hours, 12 hours, 18 hours and 24 hours of treatment. For this FRET efficiency (EFRET) as a measure of APP-PS1 proximity was calculated in each neuron at different time points after PTX or vehicle treatment (Fig. 1E). After 6 hours and 12 hours, we found significantly higher EFRET in PTX treated neurons, compared to that in cells treated with the vehicle. The 18 hours PTX treated neuronal cultures had broad distribution of FRET efficiencies, indicating somewhat heterogeneous APP-PS1 proximity/interactions in these neurons. Whereas after 24 hours, the interaction between APP and PS1 in most of the PTX treated neurons was diminished. There was no significant difference between the EFRET in neurons treated with vehicle for 6 hours, 12 hours, 18 hours and 24 hours (data not shown). Twenty-four hour treatment with PTX also diminished APP interaction with ADAM10; no effect on APP-BACE proximity was observed (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Since the APP CT and PS1 loop proximity FLIM assay does not distinguish between PS1 interaction with the full length APP and APP C-terminal fragments (CTF), we transfected primary neurons with an immediate γ-secretase substrate, GFP-tagged APP C99 CTF. Similar time dependent effect of PTX, MgCl2, and TTX was observed in GFP-C99 transfected primary neurons (Fig. 1F), suggesting that the above treatments mainly affect proximity between the APP CTF (C99) and PS/γ-secretase.

The cultures were characterized with regard to relative amount of excitatory and inhibitory neurons, as well as percentage of glial cells present. Glutamatergic neurons represent the vast majority of neuronal population (90.5±3.2%), and astrocytes and microglia account for 2.8±1.05% and 0.24±0.23%, respectively. Only neurons were selected for the FLIM analysis; presence of both GluR2 (glutamatergic) and GAD65 (GABAergic) neurons may partially contribute to the heterogeneity of the response that we observed in individual neurons (Fig.1E).

The donor fluorescence lifetime could be color-coded and mapped over entire image on a pixel-by-pixel basis showing subcellular location of the APP-PS1 interaction: blue pixels represent longer lifetimes (no FRET) and yellow-to-red pixels show presence of the FRET signal (Supplementary Fig. 2).

To ensure that toxicity due to drug treatment does not affect Aβ and EFRET measurements we performed two complementary toxicity tests. The adenylate kinase levels in the conditioned media, assessed by a non-destructive cytotoxicity assay, and the amount of adenosine-5’-triphosphate present in viable cells, evaluated by CellTiter-Glo luminescent assay (Supplementary Fig. 3), were not significantly different in all drug treatment conditions, indicating that variances in cell viability did not account for the observed change in Aβ production and/or APP-PS1 interactions.

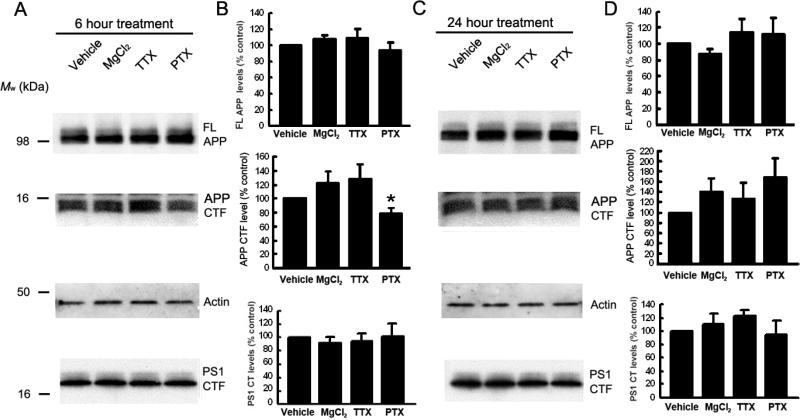

We did not detect significant difference in the level of PS1 CTF or full length APP after up- or down-regulation of neuronal activity for either 6 or 24 hours (Fig. 2). However, we observed a decrease in APP CTFs after 6 hours of neuronal activation with PTX (p<0.05, Fig. 2A and B), consistent with an increased processing of APP CTF by PS1/γ-secretase at this time point (Fig. 1). Thus, observed changes in Aβ production are not likely due to changes in APP or PS1 expression levels, and/or changes in PS1/γ-secretase endo-proteolysis.

Figure. 2.

Effect of modulation of neuronal activity on endogenous APP and PS1 levels in primary neurons. 11-14DIV wild type primary neurons were treated with vehicle, 10mM MgCl2, 1μM TTX or 100μM PTX for 6 hours (A and B) or 24 hours (C and D). Cells were lysed with 1% CHAPSO buffer. APP and PS1 expression levels were analyzed by Western blots using Rabbit anti APP-CT and mAb PS1 loop antibodies, respectively. B, D – The protein expression levels were normalized to that in vehicle-treated control cells (mean ± SEM, summary of 5 independent experiments, * p<0.05, one way ANOVA).

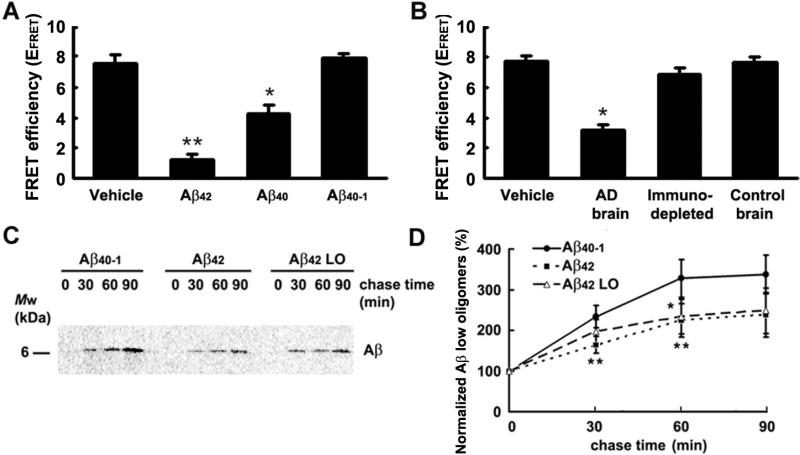

Aβ treatment decreases proximity between the APP and PS1, and reduces de novo Aβ generation

The observation that APP and PS1 are in close proximity after 6-12 hours of neuronal stimulation but move further apart 24 hours later suggests a negative feedback mechanism, in which Aβ accumulated in the media may lead to inhibition of the APP-PS1 interaction. To test this hypothesis, wild type primary neurons were treated with either synthetic or naturally secreted Aβ, and APP-PS1 interaction was analyzed by FLIM. First, 1nM of synthetic Aβ42, Aβ40, or Aβ40-1 (as a control) were added to 12 DIV neurons for 50 minutes. As shown in Fig. 3A, Aβ treatment resulted in significant decrease in the EFRET compared to that in neurons treated with vehicle alone, which indicates an increased distance between the fluorescently labeled PS1-loop and APP-CT. Treatment of the neurons with the reversed Aβ40-1 peptide had no significant effect on the EFRET, suggesting that observed increase in the APP-PS1 proximity is indeed specific to Aβ.

Figure 3.

Effect of Aβ treatment on APP - PS1 interaction and de novo Aβ secretion. (A-B): FLIM assay was performed to access proximity between endogenous APP and PS1 in 11-14 DIV primary neurons prepared from wild type mice. Neurons were treated with 1nM synthetic Aβ42, Aβ40, or Aβ40-1 (A), or with physiologically secreted Aβ isolated from AD patient or age-matched cognitively normal control brain (B). n=3 independent experiments were performed. FRET efficiency is presented as mean ± SEM; * p<0.05, **p<0.001 versus vehicle-treated controls, one way ANOVA. (C-D): Cultured Tg2576 mouse neurons pulse-labeled for 1 hour with 100μCi/ml [35S] methionine were chased for 0, 30, 60 and 90 minutes in the presence of 1nM synthetic Aβ42, low oligomeric synthetic Aβ42 (Aβ42 LO), or Aβ40-1 as a control. After immunoprecipitation with Aβ specific antibodies, the amount of [35S]-labeled Aβ in the medium was detected with a PhosphorImager (C) and quantified by Image J (D). Aβ band density at each time point was normalized to chase time 0 for each condition. Aβ42 or Aβ42 LO treated neurons were compared to Aβ40-1 treated neurons at corresponding chase time point. n=7 independent experiments were performed; mean ± SD; **p<0.001, * p<0.05, one way ANOVA.

To further examine this phenomenon, primary neurons were treated for 1 hour with naturally secreted human Aβ isolated by size exclusion chromatography from a brain of an AD patient or an age-matched cognitively normal control. The concentration of secreted Aβ in the brain fractionation samples used for treatment was ~300pM as measured by ELISA. SEC fractions 17-21 enriched in low order oligomers (Mw ~7-27kDa) but also containing some Aβ monomers were used for the treatment (Supplementary Fig.4A). Similarly to the treatment with synthetic Aβ, we detected significantly lower EFRET in neurons treated with Aβ isolated from AD brain, compared to that in neurons treated with control brain extract or with dialysis buffer as a vehicle (Fig. 3B). To ensure that the observed effect is due to Aβ species present in the AD brain sample, we incubated fractions isolated from the brain with mAb 6E10 (recognizes aa. 1-16 of Aβ) prior to neuronal treatment. As shown in Fig. 3B, the EFRET in neurons treated with the Aβ immune-depleted AD brain fractions was not significantly different from that in the vehicle or control brain fraction treated neurons. Thus, the decrease in the FRET efficiency between fluorophores tagging APP CT and PS1 loop epitopes suggests that Aβ may negatively regulate interaction between the APP and PS1, and thus, APP processing by PS1/γ-secretase.

To validate this hypothesis, and to further test the possibility of a negative feedback effect of Aβ on its own production, we performed pulse-chase experiments. For this, 14 DIV Tg2576 mouse neurons pulse labeled with [35S]-methionine were treated with 1nM Aβ40-1 as a control, 1nM exogenous synthetic Aβ42 containing low and high oligomeric species (LO+HO), or SEC purified low oligomeric Aβ42 (Aβ42 LO), fraction B2 (Supplementary Fig. 4B and 4C). We found that the level of de novo generated and secreted [35S]-labeled Aβ was significantly lower in the medium from Aβ42 treated neurons, compared to that from the Aβ40-1 treated control cells (Fig. 3C and D). The rate of de novo generation of the [35S]-labeled Aβ markedly slowed down after 60 min of the chase period in Aβ40-1 treated neurons, most likely due to diminished availability of the [35S]-labeled APP substrate. 1nM Aβ42 LO fraction had inhibition comparable to that of total Aβ42, which contains both HO+LO forms of Aβ42, indicating that this inhibition was mainly mediated by the low oligomeric Aβ42. (Supplementary Fig. 4B and 4C).

Discussion

Several studies have suggested a dependency of APP cleavage on alterations in neuronal activity (Cirrito et al., 2005; Hoe et al., 2009; Hoey et al., 2009; Kamenetz et al., 2003; Lesne et al., 2005; Marcello et al., 2007; Pierrot et al., 2004). However, they report somewhat controversial findings with neuronal activation either increasing (Cirrito et al., 2005; Hoe et al., 2009; Kamenetz et al., 2003; Lesne et al., 2005; Marcello et al., 2007; Pierrot et al., 2004), not affecting (Wei et al., 2010), or inhibiting (Hoey et al., 2009) Aβ production. Thus, in the current paper we use pharmacological modulation of neuronal activity as described by Kamenetz et al (2003) to assess the effect of neuronal activation or inhibition on Aβ production in wild type primary neurons, and focus on the changes in APP and PS1/γ-secretase interactions at endogenous level. In addition, we determine whether low, physiological concentrations of Aβ may have an effect on APP-PS1/γ-secretase interactions and Aβ generation.

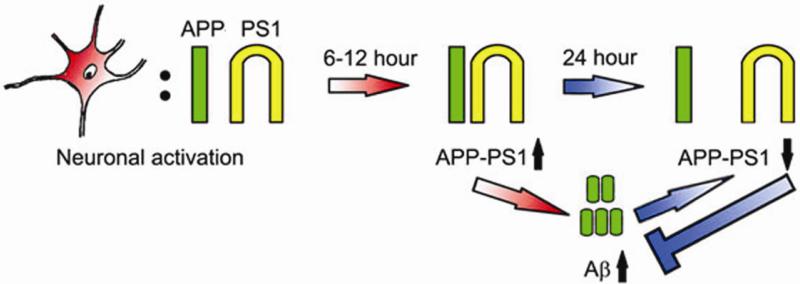

In agreement with the previously reported data obtained in neurons overexpressing APP with the Swedish mutation (Kamenetz et al., 2003), we demonstrate that neuronal activation increased, while inhibition decreased secretion of endogenous Aβ (both Aβ40 and Aβ42). The observed changes in the Aβ level were not due to altered expression of APP or active PS1/γ-secretase, since we did not detect significant differences in the levels of full length APP or PS1-CTF after manipulation of neuronal activity. Similar lack of changes in APP expression following neuronal activation was previously shown in other studies (Hoe et al., 2009; Tampellini et al., 2009). It was previously reported that 24-36 hr modulation of neuronal activity in hippocampal slice neurons expressing APP with Swedish mutation lead to a change in Aβ production supposedly via altered APP processing by β-secretase (Kamenetz et al., 2003). The authors did not detect changes in γ-secretase activity at this time point, as monitored by APP CTF generation. In the current study, by examining endogenous APP-PS1/γ-secretase interactions over time and at the earlier than 24 hour time points we found that neuronal activation had a two phase effect on APP processing by PS1/γ-secretase. Initial (monitored at 6 and 12 hours) neuronal activation increased proximity of the PS1 loop region to the APP C-terminus, as assessed by the FLIM assay in intact cells (Fig.4). This suggests an increase in APP-PS1 interactions leading to elevated Aβ production. Prolonged (up to 24 hour) neuronal activation led to a decrease in the APP-PS1 proximity indicative of decreased APP-PS1 interactions. Interestingly, similar reduction in the proximity between APP and PS1 was also detected after treatment with low, physiological concentrations of Aβ. Thus, we propose that increased, although still within the physiological range Aβ (≥300-400pM, Fig. 1B and Fig. 3B) negatively regulates its own production by interfering with APP-PS1 interactions (Fig. 4). It is not entirely clear in what form Aβ has the “negative” modulating effect. We speculate that low order oligomeric Aβ is sufficient to inhibit APP-PS1 interactions, since LO fraction of AD brain extract and the B2 low oligomeric Aβ42 fraction (Aβ42LO) containing mainly dimers-tetramers, monomers, and may be some octamers had similar “self-inhibiting” effect as non-fractionated synthetic Aβ42 which also contains higher order oligomeric forms (LO+HO).

Figure. 4.

Schema of the physiologically secreted Aβ’ negative feedback effect on APP-PS1 interactions. Neuronal activation for 6 to 12 hours (red “6-12 hour” arrow) increases proximity and thus interaction of the APP (green) and PS1 (yellow; APP-PS1↑). This leads to elevated Aβ production (short green cylinders). However, prolonged neuronal activation (blue “24 hour” arrow) and/or accumulated Aβ at ≥300-400pM concentration (bottom blue arrow) result in diminished APP-PS1 interactions (APP-PS1↓), thus preventing further Aβ generation.

It has recently been reported that synaptic stimulation elevates secreted Aβ while reducing level of the intracellular Aβ, and that increased neprilysin activity may contribute to decreased intracellular Aβ (Tampellini et al., 2009). Our finding that initial neuronal activation leads to increased Aβ production, and that elevated secreted Aβ, as well as exogenous Aβ, “inhibits” APP-PS1 interaction, may provide an additional explanation for the reduced intracellular Aβ. Aβ might “self-regulate” its own level by modulating APP-PS1/γ-secretase interactions in neurons. However, it still remains unclear how Aβ interrupts APP-PS1 interactions. It is possible that physiologically secreted Aβ may directly regulate transient interactions of APP and PS1 on the membrane by binding to either substrate or enzyme. Soluble Aβ, and to a lesser extent Aβ fibrils, have been shown to bind to APP (Lorenzo et al., 2000; Richter et al., 2010). Thus, similarly to other enzymatic reactions (Alberts et al. 2002), proteolytic processing of APP by PS1/γ-secretase may work in a self-limiting way when the final product (Aβ) prevents the availability of the substrate to its enzyme. Alternatively, based on the familial AD PS1 mutation studies, it has been hypothesized that Aβ might act as a site-directed inhibitor of γ-secretase (Shen and Kelleher, 2007).

At present, the physiological function of Aβ peptides in normal neurons is not completely understood. The normal physiological concentration of Aβ in human cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of non-demented subjects (Giedraitis et al., 2007; Seubert et al., 1992; Shoji et al., 2001) or in wild type rodent brains (Kawarabayashi et al., 2001; Puzzo et al., 2008) is in hundreds picomolar range. Numerous studies have shown that elevated Aβ levels lead to Aβ oligomerization and subsequent deposition in the brain, and that Aβ oligomers impair synaptic plasticity, cause synaptic loss and lead to neuronal death and memory abnormalities (Bero et al., 2011; Shankar et al., 2008; Walsh and Selkoe, 2007; Wu et al., 2010). Although it is well accepted that Aβ accumulation in the brain plays a major role in the pathogenesis of AD, it has also been shown that at low, physiological concentrations both Aβ40 and Aβ42 may be beneficial for neuronal survival and function. It has been reported that at low concentrations (10pM-100nM) Aβ may function as a neurotrophic factor for immature differentiating neurons (Yankner et al., 1990), can prevent the toxicity of γ-secretase inhibitor in neuronal cultures (Plant et al., 2003), and protect neurons against NMDA excitotoxic death and trophic deprivation (Giuffrida et al., 2009). The mechanism by which Aβ may exert its neuroprotective effect is not entirely clear. Aβ (Aβ40 in particular) has been proposed to have a protective effect by inhibiting Aβ42 aggregation (Kim et al., 2007), and monomeric Aβ42 has been shown to activate the IGF-1 receptors and PI-3-K cell survival pathway (Giuffrida et al., 2009). Intriguingly, a positive correlation between Aβ42 in picomolar range (both monomeric and low order oligomers) and synaptic activity, enhanced LTP and memory consolidation has been recently reported (Puzzo et al., 2008), suggesting a role of endogenous Aβ in healthy brain.

It appears that Aβ has a complex regulatory role and can implement either neuroprotective or neurotoxic effect depending on its concentration, and/or species formed. It has previously been suggested that Aβ produced in response to neuronal activation may have a normal negative feedback function by controlling neuronal hyperactivity (Kamenetz et al., 2003). We introduce yet another aspect of the proposed negative feedback role of Aβ, and present a possible molecular mechanism by which at low picomolar concentration, Aβ may contribute to its proposed neuroprotective effect in normal neurons. The “negative feedback” effect of Aβ on APP-PS1 interaction observed in our study illustrates an important biological role that Aβ could play under normal physiological conditions, which is to prevent its own synthesis due to neuronal hyperactivation. However, impaired Aβ clearance in the central nervous system of AD patients (Mawuenyega et al., 2010), as well as disruption of this negative feedback loop may lead to local overproduction of Aβ and associated with it neurotoxicity resulting in memory impairments.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Neuronal inhibition decreased endogenous APP and PS1 interactions in vitro.

Neuronal activation displayed a two-phase impact on the APP-PS1 interaction.

Low concentration of exogenous Aβ inhibited de novo Aβ synthesis in cultured neurons.

These data suggest a model of a product-enzyme negative feedback.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AG015379 (B.T.H, O.B), AG026593 (O.B), and fellowship from the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) to CML.

X.L performed FLIM, western blot and pulse chase experiments and analyzed the results; K.U did pulse chase experiment; T.H prepared and characterized Aβ from AD brain. C.M.L and M.A. performed FLIM and toxicity assay. K.U, I.P, D.K and B.T.H participated in discussions and data interpretation; O.B was responsible for the study design and coordinated the studies; X.L and O.B wrote the paper.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

amyloid β

- APP

amyloid β precursor protein

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- BACE1

β-secretase

- DIV

days in vitro

- FLIM

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- NDS

normal donkey serum

- PS1

Presenilin 1

- PTX

Picrotoxin

- TTX

Tetrodotoxin

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular biology of the cell. 4th ed. Garland Publishing; New York: 2002. Proteins. pp. 129–88. [Google Scholar]

- Berezovska O, McLean P, Knowles R, Frosh M, Lu FM, Lux SE, Hyman BT. Notch1 inhibits neurite outgrowth in postmitotic primary neurons. Neuroscience. 1999;93:433–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezovska O, Ramdya P, Skoch J, Wolfe MS, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT. Amyloid precursor protein associates with a nicastrin-dependent docking site on the presenilin 1-gamma-secretase complex in cells demonstrated by fluorescence lifetime imaging. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4560–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04560.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezovska O, Lleo A, Herl LD, Frosch MP, Stern EA, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT. Familial Alzheimer's disease presenilin 1 mutations cause alterations in the conformation of presenilin and interactions with amyloid precursor protein. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3009–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0364-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bero AW, Yan P, Roh JH, Cirrito JR, Stewart FR, Raichle ME, Lee JM, Holtzman DM. Neuronal activity regulates the regional vulnerability to amyloid-beta deposition. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:750–6. doi: 10.1038/nn.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, Yamada KA, Finn MB, Sloviter RS, Bales KR, May PC, Schoepp DD, Paul SM, Mennerick S, Holtzman DM. Synaptic activity regulates interstitial fluid amyloid-beta levels in vivo. Neuron. 2005;48:913–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedraitis V, Sundelof J, Irizarry MC, Garevik N, Hyman BT, Wahlund LO, Ingelsson M, Lannfelt L. The normal equilibrium between CSF and plasma amyloid beta levels is disrupted in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;427:127–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida ML, Caraci F, Pignataro B, Cataldo S, De Bona P, Bruno V, Molinaro G, Pappalardo G, Messina A, Palmigiano A, Garozzo D, Nicoletti F, Rizzarelli E, Copani A. Beta-amyloid monomers are neuroprotective. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10582–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1736-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoe HS, Fu Z, Makarova A, Lee JY, Lu C, Feng L, Pajoohesh-Ganji A, Matsuoka Y, Hyman BT, Ehlers MD, Vicini S, Pak DT, Rebeck GW. The effects of amyloid precursor protein on postsynaptic composition and activity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8495–506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900141200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey SE, Williams RJ, Perkinton MS. Synaptic NMDA receptor activation stimulates alpha-secretase amyloid precursor protein processing and inhibits amyloid-beta production. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4442–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6017-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetz F, Tomita T, Hsieh H, Seabrook G, Borchelt D, Iwatsubo T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron. 2003;37:925–37. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Saido TC, Shoji M, Ashe KH, Younkin SG. Age-dependent changes in brain, CSF, and plasma amyloid (beta) protein in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:372–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00372.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Onstead L, Randle S, Price R, Smithson L, Zwizinski C, Dickson DW, Golde T, McGowan E. Abeta40 inhibits amyloid deposition in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:627–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4849-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita A, Whelan CM, Smith CJ, Berezovska O, Hyman BT. Direct visualization of the gamma secretase-generated carboxyl-terminal domain of the amyloid precursor protein: association with Fe65 and translocation to the nucleus. J Neurochem. 2002;82:839–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Ali C, Gabriel C, Croci N, MacKenzie ET, Glabe CG, Plotkine M, Marchand-Verrecchia C, Vivien D, Buisson A. NMDA receptor activation inhibits alpha-secretase and promotes neuronal amyloid-beta production. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9367–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0849-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lleo A, Berezovska O, Herl L, Raju S, Deng A, Bacskai BJ, Frosch MP, Irizarry M, Hyman BT. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs lower Abeta(42) and change presenilin 1 conformation. Nat Med. 2004;10:1065–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo A, Yuan M, Zhang Z, Paganetti PA, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Staufenbiel M, Mautino J, Vigo FS, Sommer B, Yankner BA. Amyloid beta interacts with the amyloid precursor protein: a potential toxic mechanism in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:460–4. doi: 10.1038/74833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcello E, Gardoni F, Mauceri D, Romorini S, Jeromin A, Epis R, Borroni B, Cattabeni F, Sala C, Padovani A, Di Luca M. Synapse-associated protein-97 mediates alpha-secretase ADAM10 trafficking and promotes its activity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1682–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3439-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, Munsell L, Kasten T, Morris JC, Yarasheski KE, Bateman RJ. Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2010;330:1774. doi: 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrot N, Ghisdal P, Caumont AS, Octave JN. Intraneuronal amyloid-beta1-42 production triggered by sustained increase of cytosolic calcium concentration induces neuronal death. J Neurochem. 2004;88:1140–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant LD, Boyle JP, Smith IF, Peers C, Pearson HA. The production of amyloid beta peptide is a critical requirement for the viability of central neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5531–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05531.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzzo D, Privitera L, Leznik E, Fa M, Staniszewski A, Palmeri A, Arancio O. Picomolar amyloid-beta positively modulates synaptic plasticity and memory in hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14537–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2692-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter L, Munter LM, Ness J, Hildebrand PW, Dasari M, Unterreitmeier S, Bulic B, Beyermann M, Gust R, Reif B, Weggen S, Langosch D, Multhaup G. Amyloid beta 42 peptide (Abeta42)-lowering compounds directly bind to Abeta and interfere with amyloid precursor protein (APP) transmembrane dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14597–602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003026107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Esch F, Lee M, Dovey H, Davis D, Sinha S, Schlossmacher M, Whaley J, Swindlehurst C, et al. Isolation and quantification of soluble Alzheimer's beta-peptide from biological fluids. Nature. 1992;359:325–7. doi: 10.1038/359325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, Selkoe DJ. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–42. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Kelleher RJ., 3rd The presenilin hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: evidence for a loss-of-function pathogenic mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:403–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608332104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji M, Kanai M. Cerebrospinal fluid Abeta40 and Abeta42: Natural course and clinical usefulness. J Alzheimers Dis. 2001;3:313–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tampellini D, Rahman N, Gallo EF, Huang Z, Dumont M, Capetillo-Zarate E, Ma T, Zheng R, Lu B, Nanus DM, Lin MT, Gouras GK. Synaptic activity reduces intraneuronal Abeta, promotes APP transport to synapses, and protects against Abeta-related synaptic alterations. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9704–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2292-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend M, Shankar GM, Mehta T, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Effects of secreted oligomers of amyloid beta-protein on hippocampal synaptic plasticity: a potent role for trimers. J Physiol. 2006;572:477–92. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura K, Farner KC, Hashimoto T, Nasser-Ghodsi N, Wolfe MS, Koo EH, Hyman BT, Berezovska O. Substrate docking to gamma-secretase allows access of gamma-secretase modulators to an allosteric site. Nat Commun. 2010;1:130. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. A beta oligomers - a decade of discovery. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Nguyen LN, Kessels HW, Hagiwara H, Sisodia S, Malinow R. Amyloid beta from axons and dendrites reduces local spine number and plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:190–6. doi: 10.1038/nn.2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HY, Hudry E, Hashimoto T, Kuchibhotla K, Rozkalne A, Fan Z, Spires-Jones T, Xie H, Arbel-Ornath M, Grosskreutz CL, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT. Amyloid beta induces the morphological neurodegenerative triad of spine loss, dendritic simplification, and neuritic dystrophies through calcineurin activation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2636–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4456-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankner BA, Duffy LK, Kirschner DA. Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid beta protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides. Science. 1990;250:279–82. doi: 10.1126/science.2218531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.