Abstract

Recent data suggest that there may be distinct processing streams emanating from auditory cortical layer 5 and layer 6 that influence the auditory midbrain. To determine whether these projections have different physiological properties, we injected rhodamine-tagged latex tracer beads into the inferior colliculus of >30 day old mice to label these corticofugal cells. Whole-cell recordings were performed on 62 labeled cells to determine their basic electrophysiological properties and cells were filled with biocytin to determine their morphological characteristics. Layer 5 auditory corticocollicular cells have prominent Ihmediated sag and rebound currents, have relatively sluggish time constants, and can generate calcium-dependent rhythmic bursts. In contrast, layer 6 auditory corticocollicular cells are non-bursting, do not demonstrate sag or rebound currents and have short time constants. Quantitative analysis of morphology showed that layer 6 cells are smaller, have a horizontal orientation, and have very long dendrites (> 500 µm) that branch profusely both near the soma distally near the pia. Layer 5 corticocollicular cells are large pyramidal cells with a long apical dendrite with most branching near the pial surface. The marked differences in physiological properties and dendritic arborization between neurons in layer 5 and layer 6 make it likely that each type plays a distinct role in controlling auditory information processing in the midbrain.

Introduction

The brain is regularly presented with complicated and overlapping streams of acoustic information. Under normal conditions, most organisms can filter and extract specific signals out of this input stream. Many have speculated that descending, or top-down, projections may play an important role in controlling the flow of information from the auditory periphery to more central structures (Davis and Johnsrude 2007). In the auditory system, much work has been done to characterize the ascending pathways. However, there has been comparatively little work to characterize the descending projections, which emanate from virtually every level of the auditory system, and at least in the case of the corticothalamic system, numerically overwhelm the ascending projections. Since these projections send information from central structures to the periphery, they are well-suited to provide high-level cues to modulate the flow of ascending information.

One set of descending projections that has recently garnered much attention is the massive projection from the auditory cortex (AC) to the inferior colliculus (IC). The IC is a major center of convergence of ascending streams from the auditory brainstem and receives extensive descending input from the AC (Malmierca and Ryugo 2011). Therefore, corticocollicular neurons have the potential to play a key role in shaping auditory information processing. Recent work has shown that corticocollicular neurons are important for a range of critical functions of IC neurons, such as tuning for frequency, amplitude and duration (Jen, Sun et al. 2001; Suga and Ma 2003; Yan, Zhang et al. 2005) as well as mediating plastic changes in response to peripheral ear occlusion (Bajo, Nodal et al. 2010). The synaptic effects of cortical stimulation on IC neurons have not yet been fully characterized, but appear to consist of a range of effects, including pure excitation, pure inhibition and a mixture of both (Mitani, Shimokouchi et al. 1983; Jen, Sun et al. 2001). These data suggest that corticocollicular neurons may be critical for normal hearing, and can have multiple effects on their targets in the IC. Indeed, the large numbers of corticocollicular projection neurons and diversity of effects of AC manipulations on the IC suggests that there may be heterogeneity within this projection system.

Recent data using sensitive retrograde tracers demonstrate there are at least two distinct origins of the corticocollicular pathway – a large pathway from layer 5, and a pathway from a spatially separate band in lower layer 6 (Schofield 2009). This layer 6 projection has been observed across multiple species (Games and Winer 1988; Künzle 1995; Doucet, Molavi et al. 2003; Bajo and Moore 2005; Coomes, Schofield et al. 2005). It is not currently known if these two layers differentially influence the IC. However, based on other cortical descending systems, such as the corticothalamic system, differences in the laminar origin of neurons that project to the IC are likely to be important for their influence on ascending information. For example, layer 5 and layer 6 neurons projecting to the thalamus have different intrinsic physiological and morphological properties, receive different local inputs, project to different parts of the thalamus and likely have different influences on the thalamus (Llano and Sherman 2008; Llano and Sherman 2009; Theyel, Llano et al. 2010). These data have supported the hypothesis that layer 6 neurons play largely a modulatory role, whereas layer 5 neurons may drive the receptive field properties of higher order parts of the thalamus (Sherman and Guillery 2002).

Because of these functional differences, we hypothesized that layer 5 and layer 6 corticocollicular cells may differ in their intrinsic properties in ways similar to the previously observed differences in layer 5 and layer 6 corticothalamic neurons. Specifically, it is known that layer 5 corticothalamic neurons, as well as layer 5 corticotectal neurons in other systems, are large pyramidal cells with a thick apical dendrite that projects a highly branched tuft into layer 1, and demonstrate intrinsic bursting upon somatic depolarization (Schofield, Hallman et al. 1987; Hallman, Schofield et al. 1988; Wang and McCormick 1993; Kasper, Larkman et al. 1994; Llano and Sherman 2009). Layer 6 corticofugal cells have only been studied in the corticothalamic system, where they are small pyramidal cells with short apical dendrites and regular spiking properties (Brumberg, Hamzei-Sichani et al. 2003; Zarrinpar and Callaway 2006; Llano and Sherman 2009). It is notable that while layer 5 corticocollicular neurons appear to reside in similar parts of layer 5 as layer 5 corticothalamic neurons, layer 6 corticocollicular and corticothalamic neurons have non-overlapping spatial distributions. Layer 6 corticocollicular neurons sit deeper in layer 6 than the corticothalamic neurons (some have referred to this as 'layer 7') and therefore may represent a unique population of cells. Therefore, in this study, we examined and compared the electrophysiological and morphological properties of identified layer 5 and layer 6 auditory corticocollicular cells. This work represents the early steps in a longterm effort to characterize the neuronal circuitry of the auditory corticocollicular system. Part of this work has previously been presented in abstract form (Slater and Llano 2011).

Methods

General Preparation and Recording Methods

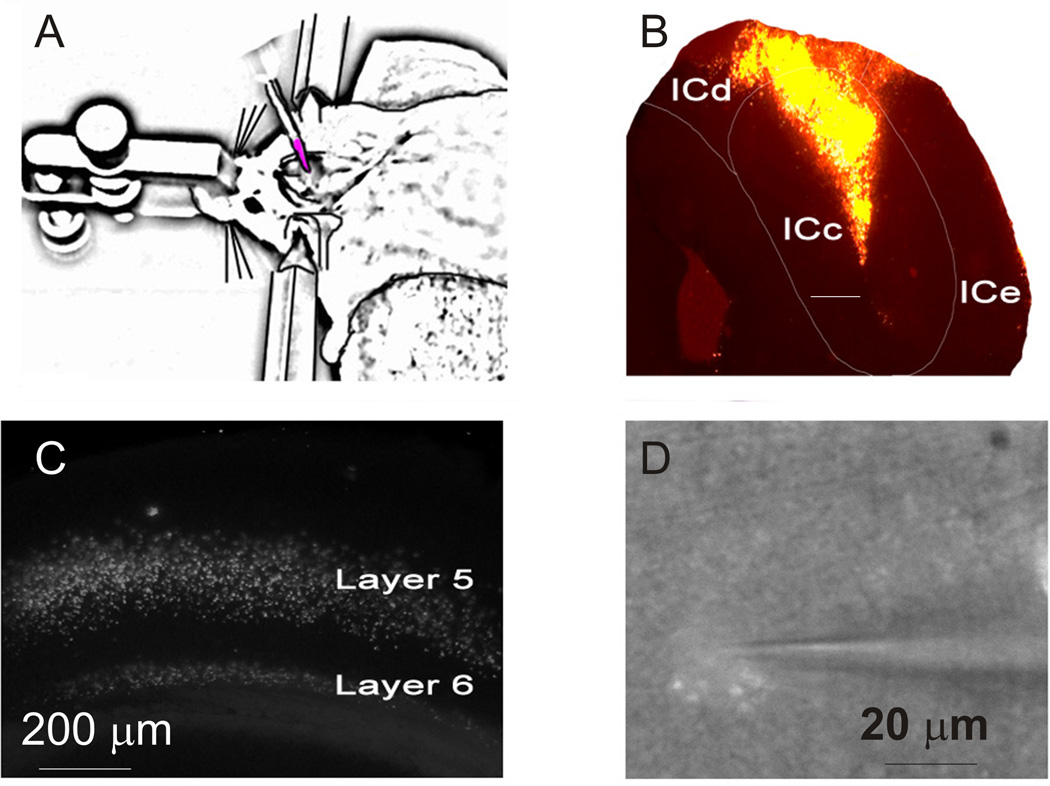

Balb/c (30–60 days of age) male mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories. Balb/c mice in the age ranges used in this study have been shown to have good hearing (Willott, Turner et al. 1998), and it is known that mice rely on complex sounds for normal behavior (Liu, Miller et al. 2003). All surgical procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois. All animals were housed in animal care facilities approved by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Every attempt was made to minimize the number of animals used and to reduce suffering at all stages of the study. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (3 mg/kg) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus, with care to avoid damage to peripheral auditory structures. Lidocaine (1%) was injected subcutaneously at incision sites prior to surgery to supplement anesthesia. Aseptic conditions were maintained throughout the surgery. Response to toe pinch was monitored, and supplements of ketamine/xylazine were administered when needed. Injection targets in the IC were localized using stereotactic coordinates (1 mm posterior to lambda, 1 mm lateral to midline, and 0.5–1 mm depth from dorsal surface, Figure 1). No attempt was made to localize the injections to any of the individual subnuclei of the IC. Although most corticocollicular projections target the dorsal cortex and lateral nucleus of the IC (Games and Winer 1988; Saldaña, Feliciano et al. 1996), we found that virtually any pressure-based injection into the IC yielded substantial label in the AC, likely caused by backfilling of the pipette tract (Figure 1). Micropipettes (tip diameter 10 µm) were filled with 10–25 nL of rhodamine-tagged polystyrene microspheres (Fluospheres F8793, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or latex microspheres (Lumafluor Retrobeads, Durham, NC) and injected into the IC over 5–10 minutes using a Nanoliter 2000 injection system (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Animals were allowed to survive for 3–7 days prior to sacrifice.

Figure 1.

Tracer injection and visualization of cells. [A] Adult mouse placed in a stereotactic apparatus with a pulled glass micropipette filled with Rhodamine-tagged microspheres and inserted into the inferior colliculus. [B] 4X image of a representative injection site in the dorsal cortex of the IC. Scale bar = 0.5 mm. [C] 2.5X image of fluorescent retrogradely-labeled cells in fixed tissue. [D] 63x Image of a patched layer 5 labeled corticocollicular cell. ICc = central nucleus of the IC, ICd = dorsal nucleus of the IC, ICe= external nucleus of the IC.

To obtain slices, mice were deeply anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), then transcardially perfused with an ice-cold high-sucrose cutting solution (in mM: 206 sucrose, 10.0 MgCl2, 11.0 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 0.5 CaCl2, 2.5 KCl, pH 7.4), and had brains removed quickly. The portion of the midbrain containing the injection site was removed and saved for re-sectioning. Coronal tissue slices (300 µm) were cut using a vibrating tissue slicer and transferred to a holding chamber containing oxygenated incubation artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) (in mM: 126 NaCl, 3.0 MgCl2, 10.0 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 1.0 CaCl2, 2.5 KCl, pH 7.4) and incubated at 32°C for 1h prior to recording.

Whole-cell recordings were performed using a visualized slice setup outfitted with infrared-differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) optics and fluorescence and performed at room temperature or 30–34°C (temperature specified with each of the Results). During recordings, tissue was bathed in recording aCSF (in mM: 126 NaCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 10.0 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 3.0 CaCl2, 2.5 KCl, pH 7.4). This formula for ACSF was used to match our previous study of the mouse auditory corticothalamic system to facilitate comparison between results (Llano and Sherman 2009). Recording pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillary tubes and had tip resistances of 2–5 MΩ when filled with solution, which contained (in mM: 117 K-gluconate, 13 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 0.07 CaCl2, 0.1 ethyleneglycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetra acetic acid, 10.0 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, 2.0 Na-ATP, 0.4 Na-GTP, and 0.5% biocytin, pH 7.3). Corticocollicular neurons were identified by fluorescence optics (Figure 1C,D). The viability of pre-labeled neurons with cut axons has been established previously (Katz, Burkhalter et al. 1984), and many groups have successfully used this approach to investigate long-range projection neurons (Brumberg, Hamzei-Sichani et al. 2003; Hattox and Nelson 2007; Brown and Hestrin 2009). We used the Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and pClamp software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) for data acquisition (20 kHz sampling). Tissue containing the IC injection sites were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline then sectioned at 50 m and mounted.

Electrophysiology analysis

Once a cell was isolated and verified to have a resting membrane potential more negative than −40 mV, a series of current injections ranging from −200 pA to + 200 pA in 25 pA steps were used to construct an I/V curve and characterize the cell’s physiological properties. Input resistance was calculated as the slope of the I/V curve, computed automatically using Clampfit software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). To compute the sag current, the voltage difference between the nadir of a hyperpolarizing trace induced by injecting 200 pA of negative current and the plateau reached after 100 ms of negative current injection was measured. This voltage was converted to a current using the input resistance and the following relationship:

Rebound current was computed by measuring the difference between the voltage from the most depolarized point just after the end of the negative current injection and the baseline voltage. This was converted to a current using input resistance in a similar manner as sag current. The membrane time constant (τ) was computed by fitting a single exponential function to the first 100 ms of the voltage change induced by injection of 200 pA negative current. Curve fitting was done in pClamp. Neurons were deemed ‘bursting’ or ‘regular spiking’ based on visual inspection because the differences between these cell types tend to be conspicuous. This qualitative approach has been used by several groups previously (Connors, Gutnick et al. 1982; Kasper, Larkman et al. 1994; Hefti and Smith 2000; Llano and Sherman 2009). Bursting cells typically demonstrate at least 3 fast spikes riding on a slower rhythmic calcium waves, though occasional 2-spike bursts were seen (See Figure 2B). The depolarizing afterpotential was defined as the difference between the voltage minimum immediately after an action potential and the voltage maximum occurring in the 10-ms period after this minimum (for an example, see Figure 3A). As previously (Hattox and Nelson 2007; Llano and Sherman 2009), the afterhyperpolarizing potential was defined as the difference between the voltage just prior to the rising fast phase of the action potential and the minimum voltage occurring within 2 ms after the action potential.

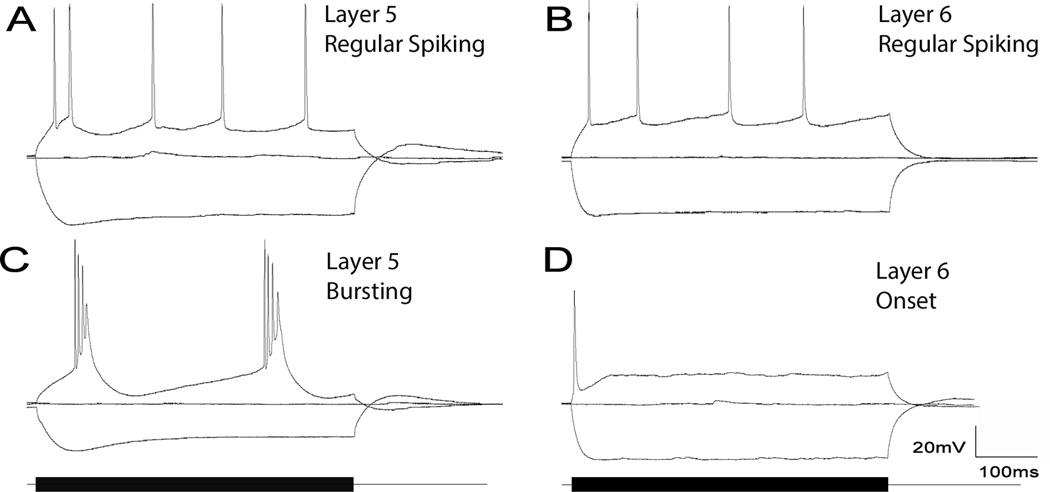

Figure 2.

[A] Layer 5 regular spiking neuron. [B] Layer 6 regular spiking neuron. [C] Layer 5 bursting neuron. [D] Layer 6 single spiking neuron.

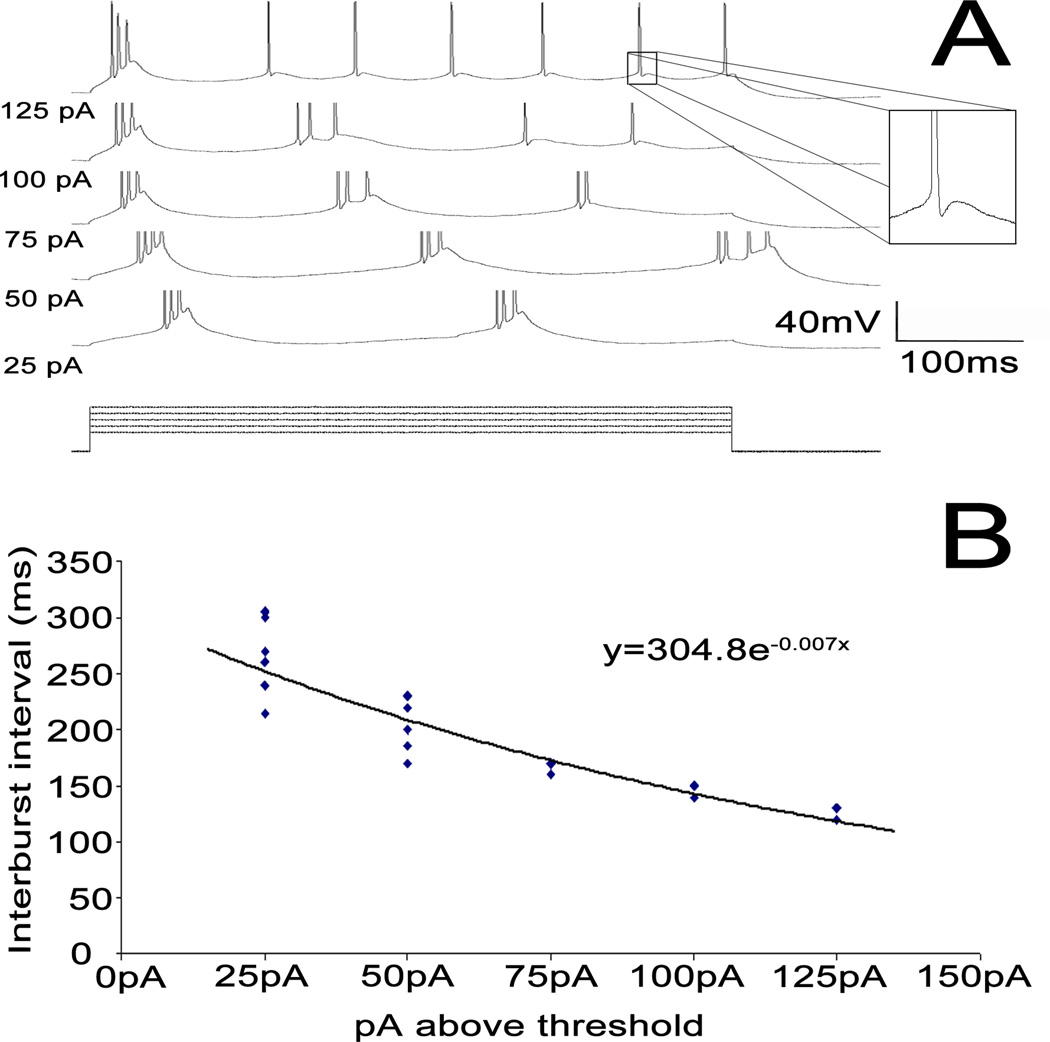

Figure 3.

Bursting frequency vs. stimulus amplitude. [A] Sample traces of a single neuron at increasing stimulus amplitudes. Spikes truncated to focus on subthreshold activity. Amplitudes listed to the left of the traces represent picoamps above threshold. [B] Single exponential fit of stimulus amplitude vs. intraburst frequency.

Cell morphology

After electrophysiology recordings, slices were placed in 4% PFA, and 1% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After a series of washes in PBS, endogenous peroxidases were quenched by incubating in 1% H2O2 in PBS for 15 minutes. The tissue was then washed in PBS-0.5% Triton X-100 to help increase membrane permeability. An avidin-biotin complex (ABC, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) was used to tag the biocytin overnight at 4°C. Ni-DAB kit was used to develop the ABC. Prepared slices were imaged using a Zeiss Axiolmager A1 (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood NY) with 2.5x, 5x, 10x, 20x (oil) and 40x (oil) objectives. Digitized traces were computed via StereoInvestigator software (Version 10.02, 32 bit) along with Neurolucida software as supplied by MBF Biosciences (Williston, VT). Manual tracing began at the soma and all visualized dendrites were followed throughout the slice until no longer visible. Reconstructed neuron data was then stored and analyzed by Neurolucida Explorer which performed the 2-dimensional Sholl analysis with 20 m radii.

Statistical Analysis

The major hypothesis of this study is that layer 5 and layer 6 corticocollicular neurons have different roles and, therefore, have different physiological and/or anatomical properties. Given the relatively small numbers of neurons analyzed, nonparametric statistics were used for all comparisons. All comparisons were done using Mann-Whitney U-test and correlations with Spearman’s rank correlation. Categorical analysis was done with Chi-square test. All measurements are given as mean ± standard deviation. Significance was assigned for comparisons that met a Bonferroni-corrected p-value, given the multiple comparisons. The correction factor was based on the number of comparisons made per hypothesis tested. The specific p-value threshold used is given in the legend of each table.

Results

Electrophysiology

A total of 62 corticocollicular cells were analyzed in this study, 32 from layer 5 and 30 cells from layer 6 from 30 mice. Eighteen layer 5 corticocollicular cells were recorded at room temperature (22°C); the other 14 at 32°C. Of the layer 6 corticocollicular cells, eight were recorded at room temperature, whereas 22 were recorded at 32°C. In most analyses, we have pooled data across temperatures because for most response properties we found very small differences between temperatures compared to differences between layers. Certain properties did change significantly with temperature (e.g. firing mode) and these are dealt with specifically in the Results.

The spiking characteristics of neurons in each layer were analyzed. Two types of layer 5 cells were observed: regular spiking (Figure 2A) and bursting cells (Figure 2B). Layer 6 cells did not show bursting, but also had two main spiking patterns. Similar to some of the cells in layer 5, there were a number of regular spiking neurons in layer 6 (25/30, Figure 2C); however, the other cell spiking type consisted of a single spike followed by a long depolarizing plateau (5/30, Figure 2D).

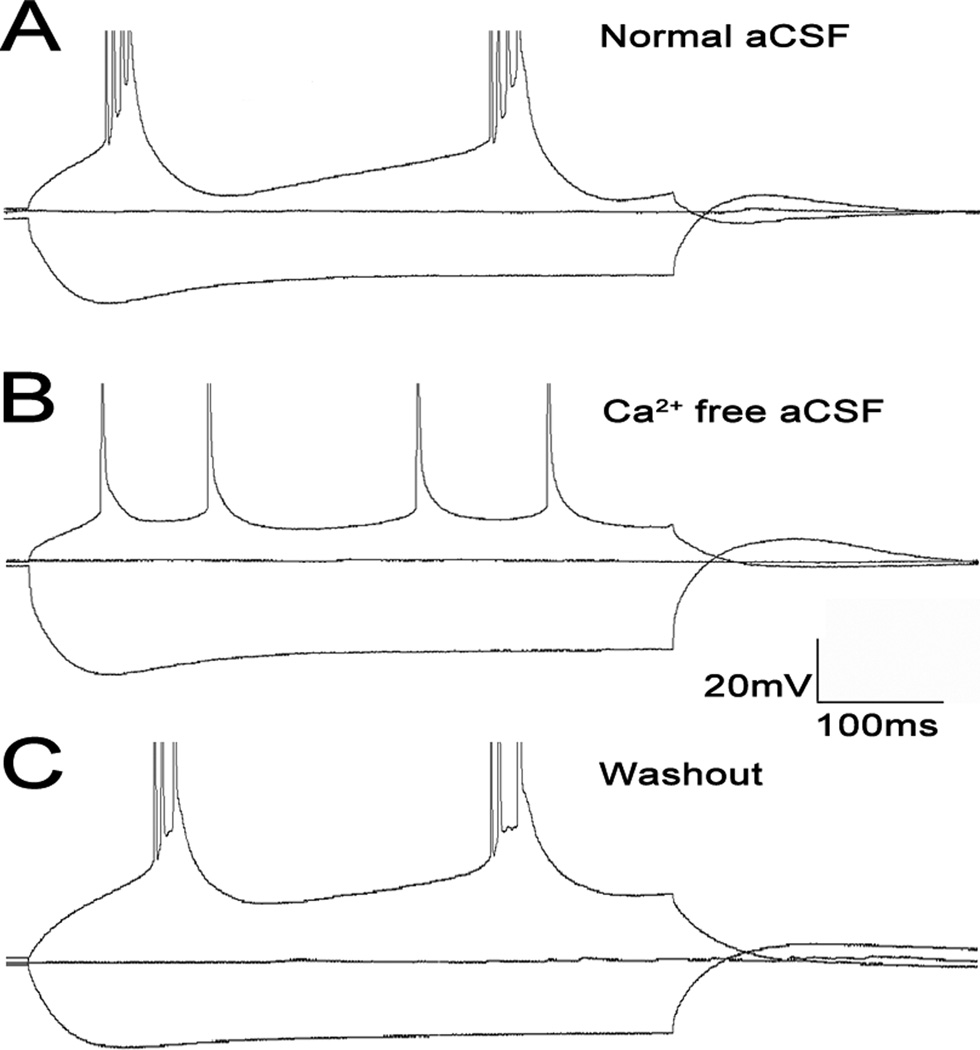

Many layer 5 bursting cells fire discrete bursts of 3–5 action potentials riding on a slower depolarization. These bursts are seen at threshold, and frequently are rhythmic, with intraburst frequency increasing with increasing amplitude. Increasing stimulation strength typically transformed the rhythmic bursting pattern to one where there was a single burst followed by a train of regular spikes (Figure 3A). These individual spikes were often followed by a depolarizing afterpotential (see Figure 3 inset). Bursting activity was only seen at 32°C (6/14 cells at 32°C). No layer 5 cells (0/18) showed bursting at room temperature, but 3/18 showed substantial (> 1 mV) depolarizing afterpotentials. Bursting was eliminated with Ca2+-free aCSF (Mg2+ replacing Ca2+), which returned upon washout with normal aCSF (compare Figures 4 A, B, and C). Depolarizing amplitude potentials also disappeared with Ca2+-free aCSF (2.4 ± 1.0 (SD) vs. 0.0 ± 0.0 (SD) mV, p < 0.001). Layer 5 regular spiking cells fired trains of individual spikes, and did not show evidence for depolarizing afterpotential.

Figure 4.

Layer 5 calcium dependent burst. Spikes truncated to focus on subthreshold activity. [A] Layer 5 bursting neuron with large sag and rebound currents. [B] washout with Ca2+ free aCSF eliminates the calcium current responsible for bursting. [C] Washout of Ca2+ aCSF with normal aCSF shows a return of bursting.

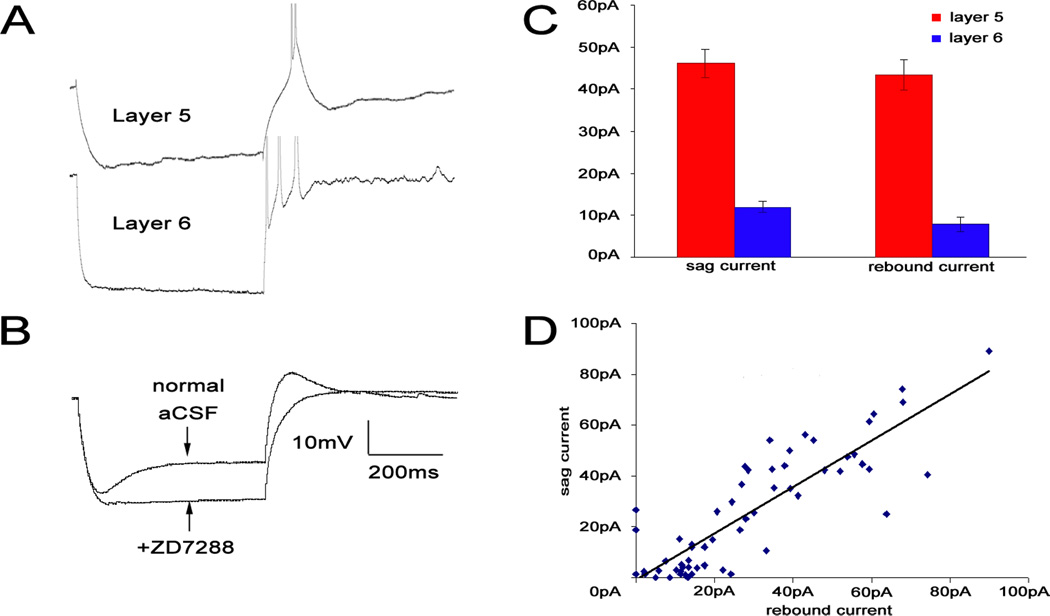

Sag currents were measured in response to hyperpolarizing pulses of –200 pA. Layer 5 cells had a much more prominent sag current, compared with layer 6 (46.4 ± 17.4 (SD) pA vs. 12.0 ± 17.3 (SD) pA, p<0.0001). A number of cells in both layer 5 (14/32) and layer 6 (4/30) showed rebound depolarization and/or spikes after hyperpolarization. Most layer 5 cells showed a prominent rebound depolarization, often producing spikes or bursts (see Figure 5A). Layer 6 cells showed a very small depolarizing rebound compared to layer 5 (43.2 ± 17.5 (SD) pA vs 7.87 ± 10.2 (SD) pA, p<0.0001). Interestingly, some layer 6 cells showed rebound spikes in the absence of a preceding depolarization (Figure 5C). The magnitude of rebound in layer 5 was significantly correlated to the magnitude of the sag current (Spearman’s ρ = 0.636, p<0.001, Figure 5C,D) and both were eliminated with the Ih specific blocker, ZD7288 (Figure 5B). Blockade of Ih had no effect on rhythmic bursting behavior.

Figure 5.

[A] Examples of rebound spikes in layer 5 and layer 6. Spikes truncated to focus on subthreshold activity. [B] Two sample traces with and without ZD7288, an Ih current specific blocker in a layer 5 cell. [C] Comparison of sag and rebound currents in layer 5 and 6 (± standard error). [D] Combined data of layer 5 and layer 6 sag versus rebound currents.

Other electrophysiological parameters were examined and are summarized in Table 1. These demonstrate that layer 5 and layer 6 corticocollicular cells differ across a range of parameters. For example, layer 5 cells had a significantly larger time constant 18.1 ± 4.3 (SD) ms compared with layer 6 cells 11.3 ± 4.5 (SD) ms (p<0.0001), larger Ih, larger rebound currents, and larger depolarizing afterpotentials. We did not, however, find significant differences in input resistances or resting potentials.

Table 1.

Summary of comparisons of layer 5 and layer 6 corticocollicular cells.

| Layer 5 Corticocollicular (n=32) |

Layer 6 Corticocollicular (n=30) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bursting** | 6/14 | 0/22 | 0.0008* |

| Sag current (pA) | 46.4 (17.4) | 12.0 (7.3) | <0.0001* |

| Rebound current (pA) | 43.2 (17.5) | 7.9 (10.2) | <0.0001* |

| Input resistance (MΩ) | 169.6 (68.3) | 191.2 (77.8) | 0.296 |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | 54.8 (9.8) | 58.8 (12.9) | 0.208 |

| Time constant (ms) | 18.1 (4.3) | 11.3 (4.5) | <0.0001* |

| Spike width at half-max (ms) | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.6) | 0.394 |

| Depolarizing afterpotential (mV) | 1.4 (2.1) | 0.14 (0.54) | 0.002* |

| Afterhyperpolarizing potential (mV) | 6.9 (7.5) | 8.7 (4.3) | 0.079 |

Asterisk and darker shading indicate statistically significantly different based on a Bonferroni-corrected p-value of 0.006 (0.05/9 comparisons).

Only 32°C data included here since no bursting was seen at room temperature. Numbers in parentheses correspond to standard deviation.

Comparison of bursting and nonbursting layer 5 cells recorded at 32°C revealed some heterogeneity within layer 5. Bursting layer 5 cells had lower input resistance (101 ± 17 (SD) M vs. 199 ± 38 (SD) M, p=0.0007) and showed trends for having larger sag currents (64.6 ± 17.4 (SD) pA vs. 42.2 ± 12.7 (SD) pA, p=0.042) and shorter time constants (16.8 ± 2.3 (SD) ms vs. 19.8 ± 2.6 (SD) pA, p=0.046). These data are found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of comparisons of layer 5 bursting vs. non-bursting cells.

| Layer 5 Bursting (n=6) |

Layer 5 Non-bursting (n=8) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sag current (pA) | 64.6 (17.4) | 42.2 (12.7) | 0.042 |

| Rebound current (pA) | 55.6 (18.3) | 44.3 (17.4) | 0.282 |

| Input resistance (MΩ) | 101 (17) | 199.0 (38) | <0.001 |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | −55.3 (5.6) | −50.0 (6.1) | 0.121 |

| Time constant (ms) | 16.8 (2.3) | 19.8 (2.6) | 0.046 |

| Depolarizing afterpotential (mV) | 3.2 (2.0) | 1.7 (2.4) | 0.139 |

Asterisk and darker shading indicate statistically significantly different based on a Bonferroni-corrected p-value of 0.008 (0.05/6 comparisons). Only 32°C data included here since no bursting was seen at room temperature. Numbers in parentheses correspond to standard deviation.

Temperature effects

The effect of temperature on the electrophysiological properties of corticocollicular neurons was examined (see Table 3). Across both layer 5 and layer 6 cells, no statistically significant differences in sag currents, rebound currents, resting membrane potential, input resistance or time constant were observed. At 32°C, spike half-width significantly shortened in layer 6 cells, and showed a trend to shorten in layer 5 cells (2.9 vs 2.2 ms in layer 6, p=0.003 and 3.0 vs 2.2 ms in layer 5, p = 0.04). There were nonsignificant changes in sag and rebound currents and resting potentials in layer 5 cells recorded at physiological temperatures (sag, 51.8 vs 42.2 pA, p = 0.16, and rebound 49.2 vs 38.6 pA, p = 0.125). Importantly, when cells recorded at room temperature were excluded from the analysis, all of the significant differences between layer 5 cells and layer 6 cells described above remained highly significant (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of temperature effects.

| Layer 5 Room Temp (n=18) |

Layer 5 32 C (n=14) |

p value (Layer 5 RT vs. 32C) |

Layer 6 Room Temp (n=8) |

Layer 6 32 C (n=22) |

p value (Layer 6 RT vs. 32C) |

p value (Layer 5 vs Layer 6 at 32C) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sag current (pA) | 42.2 (15.9) | 51.8 (18.3) | 0.130 | 10.7 (7.0) | 12.5 (7.5) | 0.549 | <0.0001* |

| Rebound current (pA) | 38.6 (16.1) | 49.2 (18.1) | 0.125 | 5.2 (5.6) | 8.9 (11.4) | 0.252 | <0.0001* |

| Input resistance (MΩ) | 179.2 (75.4) | 157.3 (58.3) | 0.420 | 239.4 (84.4) | 173.6 (69.1) | 0.056 | 0.531 |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | 57.7 (10.5) | 51.2 (7.6) | 0.083 | 52.0 (9.4) | 61.3 (13.2) | 0.114 | 0.017 |

| Time constant (ms) | 17.8 (5.3) | 18.5 (2.8) | 0.560 | 14.0 (4.8) | 10.3 (4.0) | 0.024 | <0.0001* |

| Spike width at half-max (ms) | 3.0 (1.0) | 2.2 (0.8) | 0.043 | 2.9 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.6) | 0.003* | 0.928 |

| Depolarizing afterpotential (mV) | 0.75 (1.8) | 2.2 (2.2) | 0.011 | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.549 | 0.003* |

| Afterhyperpolarizing potential (mV) | 6.2 (5.1) | 7.8 (9.8) | 0.664 | 8.0 (1.5) | 8.9 (4.5) | 0.597 | 0.395 |

Asterisk and darker shading denote statistical significance using a Bonferroni-corrected p value of 0.006 (0.05/8 comparisons for each underlying hypothesis). Numbers in parentheses correspond to standard deviation. RT = room temperature

Cell morphology

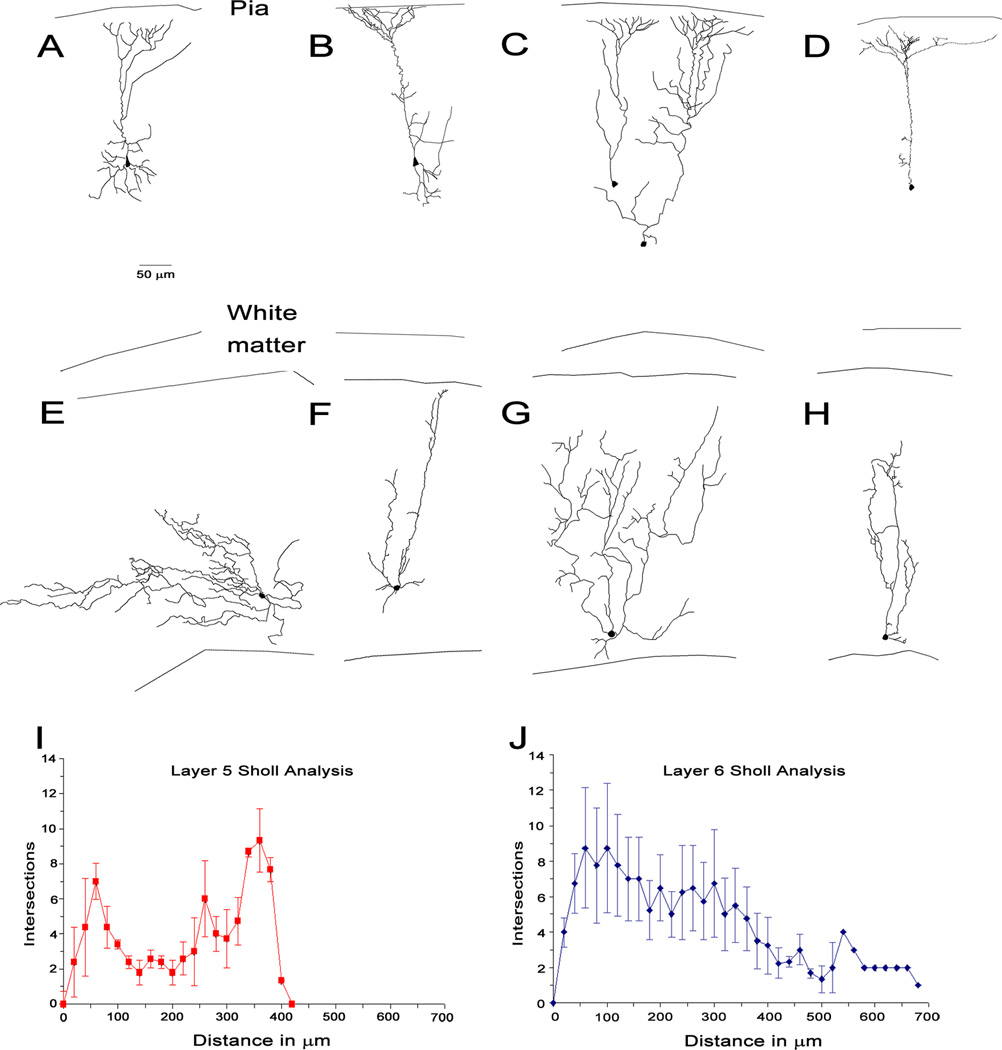

Five layer 5 cells and four layer 6 cells were recovered for morphological analysis. Substantial differences were observed between layer 5 and layer 6 corticocollicular cell morphology. All five layer 5 cells had similar morphologies, demonstrating a pyramidal-shaped cell body with a single prominent apical dendrite with a tuft of dendritic branching in upper layer 2/3 and layer 1 (Figure 6A-D). Sholl analysis revealed two peaks of branching: one near the soma and another at approximately 350 m away, corresponding to the branching near the pia seen qualitatively (Figure 6I,J). Layer 6 cells have a different appearance than layer 5 cells, with smaller horizontally-oriented soma, and have multiple small dendrites, with profuse branching, and with some cells having dendrites which extend to the pia. Sholl analysis reveals most branching occurring in the proximal regions of the dendrites, and demonstrates that these cells may have extremely long dendrites (> 500 m, Figure 6E-H).

Figure 6.

[A-D] Traces of layer 5 neurons filled with biocytin, recovered and traced in Neurolucida. E-H. Traces of layer 6 similarly traced. I,J. Combined Sholl analyses of layer 5 and layer 6 (± standard error).

Discussion

In this study, a number of physiological and morphological differences between layer 5 and layer 6 auditory corticocollicular cells were observed. Many layer 5 corticocollicular neurons demonstrated calcium-dependent bursting in response to somatic depolarization and this bursting was often repetitive and rhythmic. In addition, layer 5 corticocollicular cells had prominent Ih-dependent sag and rebound currents. None of these properties was seen in layer 6 corticocollicular cells. Morphologically, layer 5 cells were large and had a pyramidal shape and had tufted branching near the border of layer 2/3 with layer 1. Layer 6 cells showed regular spiking and had profusely branched and very long mostly radially-oriented dendrites, with some dendrites extending to the pia. These data suggest that layer 5 and layer 6 corticocollicular cells may receive different sets of cortical inputs, and that they are likely respond to these inputs with different spiking patterns. These data are consistent with the general hypothesis that layer 5 and layer 6 AC neurons send different messages to the IC.

Methodological considerations

It is possible that these results may have been affected by the pooling of data obtained at different temperatures. Indeed, we saw no bursting at 22°C therefore, physiological temperatures are necessary to see bursting. It is notable that even though bursting was not seen at room temperature, depolarizing afterpotentials were seen. These afterpotentials have also been seen in immature nonbursting layer 5 corticofugal neurons (Hattox and Nelson 2007; Llano and Sherman 2009), and are calcium-dependent (Friedman and Gutnick 1989; Mason and Larkman 1990; Friedman, Arens et al. 1992), and may be derived from the same underlying mechanism responsible for bursting. The temperature-dependence of bursting is also consistent with previous work demonstrating temperature-dependent changes in dendritic calcium dynamics in layer 5 cortical neurons (Markram, Helm et al. 1995). Increasing temperature from room temperature to 32°C did cause some predictable trends in the data, such as shortening the action potential duration. However, for the cell parameters reported here that differed between layer 5 and layer 6 cells (Ih, rebound current, tau, depolarizing afterpotential), the differences due to temperature were relatively small relative to differences due to layer of origin. In addition, when only data obtained at physiological temperatures were compared, the differences between layer 5 and layer 6 neurons remained highly significant (Table 3). It is likely that obtaining data at a single temperature would have produced less variance within each group, but would not have changed the fundamental findings of this study.

Another potential concern is the small numbers of neurons recovered for morphological analysis. This study was done exclusively in adult animals because of our previous work demonstrating clear age-dependence of bursting (Llano and Sherman 2009). In our experience, recovery of cells for morphological analysis is more challenging in older animals. However, the small number of recovered cells (n=9 total or 15%), was sufficient to detect the large qualitative differences that differentiate layer 5 and layer 6 corticocollicular cells. The small number of cells did preclude parsing physiological parameters based on morphological subtype.

General discussion

The current morphologic and electrophysiological findings in layer 5 corticocollicular neurons are similar to what has been seen in layer 5 of the auditory cortex in general (Hefti and Smith 2000; Wahl, Marzinzik et al. 2008) in other layer 5 corticofugal neurons, including those that project to the auditory thalamus (Llano and Sherman 2009) and those that project from the visual cortex to the superior colliculus (Schofield, Hallman et al. 1987; Kasper, Larkman et al. 1994). There is a substantial amount of heterogeneity in these cells’ biophysical properties, part of which may be explained by whether the cells fire in bursts or not. For example, bursting cells had lower input resistances than regular spiking cells, suggesting that these cells may have a larger volume (Table 2), consistent with previous descriptions of differences between bursting and nonbursting layer 5 cells (Chagnac-Amitai, Luhmann et al. 1990).

The bursting observed appears identical to bursting seen in previous studies (Connors, Gutnick et al. 1982). The mechanism underlying bursting has been studied by several investigators (Friedman and Gutnick 1989; Markram and Sakmann 1994; Franceschetti, Guatteo et al. 1995; Larkum, Kaiser et al. 1999) who have found that such bursting is likely created by a dendritic low-threshold voltage-dependent calcium current, which is supported by our finding that bursting is eliminated with Ca2+ free aCSF. It is likely that the prevalence of bursting seen in the current study represents an underestimate of the proportion of cells that burst, since previous investigators have found layer 5 cortical cells which do not burst with somatic depolarization, but only burst with dendritic depolarization (Schwindt and Crill 1999). Because many inputs to layer 1 comprise fibers from distant cortical areas and long-range thalamocortical axonal branches, it is possible that layer 5 corticocollicular neurons integrate information from distant sources with local inputs from layers 2/3, 4, or 5 (Cetas, de Venecia et al. 1999; Oda, Kishi et al. 2004). It has been proposed that such dendritic morphology, coupled with active dendritic calcium conductances, allows these neurons to serve as coincidence detectors for upper and middle layer input (Larkum, Zhu et al. 1999; Llinas, Leznik et al. 2002). It should be noted that spike widths in this study (mean = 2.2 ms at 32°C) were longer than those observed in a study of layer 5 neurons in the rat auditory cortex (mean = 0.72–1.23 ms at 35°C) (Hefti and Smith 2000). There were several methodological differences that may explain this discrepancy (sharp vs. patch recordings, temperature differences, species differences (rat vs. mouse), ACSF formula differences, etc.. Any or all of these may explain these different spike widths observed.

The similarities between layer 5 corticocollicular and layer 5 corticothalamic cells extend beyond bursting. For example, both layer 5 corticocollicular cells and layer 5 corticothalamic cells show high expression of Ih-mediated sag and rebound currents, have large depolarizing afterpotentials and have large somata with thick tufted apical dendrites that extend into layer 1 (Llano and Sherman 2009). These similarities in physiological and morphological properties suggest that layer 5 neurons that project to the IC and thalamus may have common response properties and perhaps have similar roles in information processing. It is also possible that there are subsets of layer 5 cells that project to both the thalamus and IC and therefore send identical messages to these two structures. Work from the motor, visual and somatosensory systems suggest that single layer 5 cells may, in fact, branch to many subcortical targets, including thalamus and midbrain (Deschênes, Bourassa et al. 1994; Bourassa, Pinault et al. 1995; Kita and Kita 2012). If there are common layer 5 cells that project to both structures, any theory about the role of layer 5 corticocollicular neurons will have to be consistent with what is known about the corticothalamic system, and vice-versa. Future work using double-labeling techniques or single-axon tracing techniques will better clarify this issue of common layer 5 cells that branch to both IC and thalamus.

Layer 6 corticocollicular neurons are a relatively recently-described population of neurons. Their numbers are small compared to layer 5, and for that reason were not observed (or at least were not described) in older studies with less sensitive tracers. Unlike layer 5, where corticocollicular cells resemble their corticothalamic counterparts, layer 6 corticocollicular cells bear little morphological resemblance to layer 6 corticothalamic cells. Layer 6 corticothalamic cells are found in the middle of layer 6, and are small pyramidal cells with short dendrites (Zarrinpar and Callaway 2006; Llano and Sherman 2009). Layer 6 corticocollicular cells are in the extreme depth of the cortex, often found in the white matter and have cell bodies with a variety of orientations (Schofield 2009). Based on our data and observations by Schofield (2009), layer 6 corticocollicular cells appear to comprise a very small minority of the total number of neurons in layer 6, while layer 5 corticocollicular cells are much more numerous, comprising a substantial proportion of layer 5 neurons. We found that layer 6 corticocollicular cells had surprisingly long dendrites, some > 1 mm in length, making these among the longest dendrites in the cortex. Most of these dendritic trees had a radial orientation, although one extended laterally for approximately 500µm (Figure 6E). These suggest that, unlike layer 6 corticothalamic cells, these cells are likely sampling inputs from relatively long distances. This raises new questions about the integrative properties of these long dendrites, which are likely too long to permit passive propagation of subthreshold signals from the distal dendrites to the soma. Given the distance that the fibers cover, any information from the distal portions of the dendritic tree would likely need to be conveyed via active conductances.

Layer 5 and layer 6 corticocollicular cells were distinguishable based on the high expression of Ih (sag) current in layer 5 cells. The high level of this current has been seen in other layer 5 corticofugal neurons (Kasper, Larkman et al. 1994) and likely contributed to the pronounced rebound depolarizations seen in these cells. Ih may contribute to several other attributes of layer 5 cells, such as their slightly depolarized resting potentials, and may diminish their input resistance, which would diminish the length constant of these neurons (Robinson and Siegelbaum 2003). Ih may also contribute to persistent activity seen in other parts of the cortex in vivo (Winograd, Destexhe et al. 2008), though the in vivo properties of auditory layer 5 corticocollicular cells has not yet been investigated.

Functional significance of the current findings

These data do not yet tell us whether layer 5 and layer 6 neurons have different roles in modifying the IC. However, they do raise the possibility that these neurons sample different information from the cortex, and likely send different patterns of information to the IC. Bursting, in general, has a greater likelihood of driving post-synaptic responses than individual spikes, particularly in depressing synapses (Lisman 1997); Reinagel, Godwin et al. 1999; Swadlow and Gusev 2001). In the visual corticocollicular synapse, layer 5 bursting activity has been associated with large post-synaptic effects when measured at the population level (Bereshpolova, Stoelzel et al. 2006). Unfortunately, the synaptic properties of the auditory corticocollicular synapse have not yet been studied in any detail. It is notable that AC stimulation can cause a variety of physiological changes in the IC, encompassing excitation, inhibition and combinations of these (Mitani, Shimokouchi et al. 1983; Jen, Sun et al. 2001). In addition, the growing literature on the effects of AC manipulations on the IC suggests that the effects of AC stimulation are seen across a broad array of tuning functions and timescales (Suga and Ma 2003; Yan, Zhang et al. 2005; Bajo, Nodal et al. 2010). It may be that part of this heterogeneity may be explained by the possibility that most experimental manipulations of the auditory cortex will affect both layer 5 and layer 6 cells, and therefore produce heterogeneous results. Future work will clarify whether the different inputs to layer 5 and layer 6 corticocollicular cells and their different temporal dynamics differentially affects IC neurons.

Highlights.

We compare layer 5 and layer 6 auditory corticocollicular neurons.

Layer 5 cells can have calcium-dependent bursting and large Ih sag/rebound currents.

Layer 5 cells have thick apical dendrites that contain a tuft near layer 1.

Layer 6 cells do not burst and have small Ih currents.

Layer 6 cells have very long and highly branched radially-oriented dendrites.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bajo VM, Moore DR. Descending projections from the auditory cortex to the inferior colliculus in the gerbil, Meriones unguiculatus. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;486(2):101–116. doi: 10.1002/cne.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajo VM, Nodal FR, et al. The descending corticocollicular pathway mediates learning-induced auditory plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(2):253–260. doi: 10.1038/nn.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereshpolova Y, Stoelzel CR, et al. The Impact of a Corticotectal Impulse on the Awake Superior Colliculus. J. Neurosci. 2006;26(8):2250–2259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4402-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa J, Pinault D, et al. Corticothalamic projections from the cortical barrel field to the somatosensory thalamus in rats: a single-fibre study using biocytin as an anterograde tracer. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;7:19–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SP, Hestrin S. Intracortical circuits of pyramidal neurons reflect their long-range axonal targets. Nature. 2009;457(7233):1133–1136. doi: 10.1038/nature07658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumberg JC, Hamzei-Sichani F, et al. Morphological and Physiological Characterization of Layer VI Corticofugal Neurons of Mouse Primary Visual Cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89(5):2854–2867. doi: 10.1152/jn.01051.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetas JS, de Venecia RK, et al. Thalamocortical afferents of Lorente de Nó: medial geniculate axons that project to primary auditory cortex have collateral branches to layer I. Brain Research. 1999;830(1):203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagnac-Amitai Y, Luhmann HJ, et al. Burst generating and regular spiking layer 5 pyramidal neurons of rat neocortex have different morphological features. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;296(4):598–613. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors BW, Gutnick MJ, et al. Electrophysiological properties of neocortical neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1982;48(6):1302–1320. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.6.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coomes DL, Schofield RM, et al. Unilateral and bilateral projections from cortical cells to the inferior colliculus in guinea pigs. Brain Research. 2005;1042(1):62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH, Johnsrude IS. Hearing speech sounds: Top-down influences on the interface between audition and speech perception. Hearing Research. 2007;229(1–2):132–147. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes M, Bourassa J, et al. Corticothalamic projections from layer V cells in rat are collaterals of long-range corticofugal axons. Brain Research. 1994;664(1–2):215–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91974-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet J, Molavi D, et al. The source of corticocollicular and corticobulbar projections in area Te1 of the rat. Experimental Brain Research. 2003;153(4):461–466. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1604-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschetti S, Guatteo E, et al. Ionic mechanisms underlying burst firing in pyramidal neurons: intracellular study in rat sensorimotor cortex. Brain Research. 1995;696(1–2):127–139. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00807-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A, Arens J, et al. Slow depolarizing afterpotentials in neocortical neurons are sodium and calcium dependent. Neuroscience Letters. 1992;135(1):13–17. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90125-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A, Gutnick MJ. Intracellular Calcium and Control of Burst Generation in Neurons of Guinea-Pig Neocortex in Vitro. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1989;1(4):374–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1989.tb00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Games KD, Winer JA. Layer V in rat auditory cortex: Projections to the inferior colliculus and contralateral cortex. Hearing Research. 1988;34(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallman LE, Schofield BR, et al. Dendritic morphology and axon collaterals of corticotectal, corticopontine, and callosal neurons in layer V of primary visual cortex of the hooded rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1988;272(1):149–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.902720111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattox AM, Nelson SB. Layer V Neurons in Mouse Cortex Projecting to Different Targets Have Distinct Physiological Properties. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98(6):3330–3340. doi: 10.1152/jn.00397.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefti BJ, Smith PH. Anatomy, Physiology, and Synaptic Responses of Rat Layer V Auditory Cortical Cells and Effects of Intracellular GABAA Blockade. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83(5):2626–2638. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen P, Sun X, et al. An electrophysiological study of neural pathways for corticofugally inhibited neurons in the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus of the big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus. Experimental Brain Research. 2001;137(3–4):292–302. doi: 10.1007/s002210000637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper EM, Larkman AU, et al. Pyramidal neurons in layer 5 of the rat visual cortex. I. Correlation among cell morphology, intrinsic electrophysiological properties, and axon targets. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1994;339(4):459–474. doi: 10.1002/cne.903390402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Burkhalter A, et al. Fluorescent latex microspheres as a retrograde neuronal marker for in vivo and in vitro studies of visual cortex. Nature. 1984;310(5977):498–500. doi: 10.1038/310498a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita T, Kita H. The Subthalamic Nucleus Is One of Multiple Innervation Sites for Long-Range Corticofugal Axons: A Single-Axon Tracing Study in the Rat. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(17):5990–5999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5717-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künzle H. Regional and Laminar Distribution of Cortical Neurons Projecting to Either Superior or Inferior Colliculus in the Hedgehog Tenrec. Cerebral Cortex. 1995;5(4):338–352. doi: 10.1093/cercor/5.4.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkum ME, M. Kaiser KM, et al. Calcium electrogenesis in distal apical dendrites of layer 5 pyramidal cells at a critical frequency of backpropagating action potentials. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999;96(25):14600–14604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkum ME, Zhu JJ, et al. A new cellular mechanism for coupling inputs arriving at different cortical layers. Nature. 1999;398(6725):338–341. doi: 10.1038/18686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE. Bursts as a unit of information: making unreliable synapses reliable. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20(1):38–43. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Miller K, et al. Acoustic variability and distinguishability among mouse ultrasound vocalizations. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2003;114(6):3412–3422. doi: 10.1121/1.1623787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano DA, Sherman SM. Evidence for nonreciprocal organization of the mouse auditory thalamocortical-corticothalamic projection systems. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2008;507(2):1209–1227. doi: 10.1002/cne.21602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano DA, Sherman SM. Differences in Intrinsic Properties and Local Network Connectivity of Identified Layer 5 and Layer 6 Adult Mouse Auditory Corticothalamic Neurons Support a Dual Corticothalamic Projection Hypothesis. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19(12):2810–2826. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas RR, Leznik E, et al. Temporal binding via cortical coincidence detection of specific and nonspecific thalamocortical inputs: A voltagedependent dye-imaging study in mouse brain slices. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99(1):449–454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012604899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmierca MS, Ryugo DK. Winer JA, Schreiner CE. Descending Connections of Auditory Cortex to the Midbrain and Brain Stem The Auditory Cortex. Springer US; 2011. pp. 189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Helm PJ, et al. Dendritic calcium transients evoked by single back-propagating action potentials in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 1995;485(Pt_1):1–20. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Sakmann B. Calcium Transients in Dendrites of Neocortical Neurons Evoked by Single Subthreshold Excitatory Postsynaptic Potentials via Low-Voltage-Activated Calcium Channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994;91(11):5207–5211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason A, Larkman A. Correlations between morphology and electrophysiology of pyramidal neurons in slices of rat visual cortex. II. Electrophysiology. J. Neurosci. 1990;10(5):1415–1428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-05-01415.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani A, Shimokouchi M, et al. Effects of stimulation of the primary auditory cortex upon colliculogeniculate neurons in the inferior colliculus of the cat. Neuroscience Letters. 1983;42(2):185–189. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda S, Kishi K, et al. Thalamocortical projection from the ventral posteromedial nucleus sends its collaterals to layer I of the primary somatosensory cortex in rat. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;367(3):394–398. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinagel P, Godwin D, et al. Encoding of Visual Information by LGN Bursts. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(5):2558–2569. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RB, Siegelbaum SA. Hyperpolarization-activated cation currents: From molecules to physiological function. Annual Review of Physiology. 2003;65(1):453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña E, Feliciano M, et al. Distribution of descending projections from primary auditory neocortex to inferior colliculus mimics the topography of intracollicular projections. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1996;371(1):15–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960715)371:1<15::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR. Projections to the inferior colliculus from layer VI cells of auditory cortex. Neuroscience. 2009;159(1):246–258. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR, Hallman LE, et al. Morphology of corticotectal cells in the primary visual cortex of hooded rats. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1987;261(1):85–97. doi: 10.1002/cne.902610107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwindt P, Crill W. Mechanisms Underlying Burst and Regular Spiking Evoked by Dendritic Depolarization in Layer 5 Cortical Pyramidal Neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(3):1341–1354. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.3.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW. The role of the thalamus in the flow of information to the cortex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2002;357(1428):1695–1708. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater B, Llano D. Layer-specific differences in physiological properties in the mouse auditory corticocollicular system. Society for Neuroscience. 2011 Abstracts 912.02. [Google Scholar]

- Suga N, Ma X. Multiparametric corticofugal modulation and plasticity in the auditory system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(10):783–794. doi: 10.1038/nrn1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swadlow H, Gusev A. The impact of 'bursting' thalamic impulses at a neocortical synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(4):402–408. doi: 10.1038/86054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theyel BB, Llano DA, et al. The corticothalamocortical circuit drives higher-order cortex in the mouse. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(1):84–88. doi: 10.1038/nn.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl M, Marzinzik F, et al. The Human Thalamus Processes Syntactic and Semantic Language Violations. Neuron. 2008;59(5):695–707. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, McCormick D. Control of firing mode of corticotectal and corticopontine layer V burst-generating neurons by norepinephrine, acetylcholine, and 1S,3R- ACPD. J. Neurosci. 1993;13(5):2199–2216. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-02199.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF, Turner JG, et al. The BALB/c mouse as an animal model for progressive sensorineural hearing loss. Hearing Research. 1998;115(1–2):162–174. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winograd M, Destexhe A, et al. Hyperpolarization-activated graded persistent activity in the prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(20):7298–7303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800360105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Zhang Y, et al. Corticofugal Shaping of Frequency Tuning Curves in the Central Nucleus of the Inferior Colliculus of Mice. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2005;93(1):71–83. doi: 10.1152/jn.00348.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrinpar A, Callaway EM. Local Connections to Specific Types of Layer 6 Neurons in the Rat Visual Cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95(3):1751–1761. doi: 10.1152/jn.00974.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]