Abstract

Objective

This cross sectional study aimed to characterize fears of recurrence among women newly diagnosed with gynecologic cancer. The study also evaluated models predicting the impact of recurrence fears on psychological distress through social and cognitive variables.

Methods

Women (N = 150) who participated in a randomized clinical trial comparing a coping and communication intervention to a supportive counseling intervention to usual care completed baseline surveys that were utilized for the study. The survey included the Concerns about Recurrence Scale (CARS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Impact of Event Scale (IES), and measures of social (holding back from sharing concerns and negative responses from family and friends) and cognitive (positive reappraisal, efficacy appraisal, and self-esteem appraisal) variables. Medical data was obtained via medical chart review.

Results

Moderate-to-high levels of recurrence fears were reported by 47% of the women. Younger age (p < .01) and functional impairment (p < .01) correlated with greater recurrence fears. A social-cognitive model of fear of recurrence and psychological distress was supported. Mediation analyses indicated that as a set, the social and cognitive variables mediated the association between fear of recurrence and both depression and cancer-specific distress. Holding back and self-esteem showed the strongest mediating effects.

Conclusion

Fears of recurrence are prevalent among women newly diagnosed with gynecologic cancer. Social and cognitive factors play a role in women’s adaptation to fears and impact overall psychological adjustment. These factors may be appropriate targets for intervention.

Keywords: Recurrence fears, gynecological cancer, social-cognitive processing, psychological adaptation

INTRODUCTION

The diagnosis and treatment of gynecologic cancer has considerable physical and psychosocial impact. Treatment regimens cause potentially unpleasant side effects such as pain, fatigue, urinary complications, vaginal dryness, reduced vaginal elasticity, sexual dysfunction, and premature menopause among younger women [1–3]. The emotional impact includes clinical levels of depression in one quarter [4] and cancer-specific distress in more than half of women with ovarian cancer [5]. Similar patterns occur in cervical, endometrial, and vulvar cancer patients [6–8]. Younger age, advanced disease, personal coping, interpersonal stressors and physical impairment are predictors of distress [6,9].

A common source of distress among most patients is the fear of recurrence [10–15]. Less is known about such fears in gynecologic cancer compared to other cancer populations, despite the fact that certain types of gynecologic cancers have a poor prognosis and a high recurrence rate [16]. Between one-fifth and one-half of women receiving treatment for ovarian cancer [17] and ovarian cancer survivors [18, 19] report recurrence fears, as do those with cervical and endometrial cancers [20]. The limitations of these studies include the lack of standardized assessment methods, a limited inclusion of other gynecologic cancers, and a limited focus on newly diagnosed women [18, 19, 21].

The existing studies indicate that recurrence fears are associated with psychological distress [19, 21] and tend to be greater among patients who are younger [22–24], have more advanced disease [25], and are more physically impaired [12, 19, 21]. Almost nothing is known about individual and interpersonal factors related to recurrence fears. One study linked greater social support to less fear of recurrence [21]. There is a need to better understand these factors to assist in identifying patients who may benefit from psychological support.

This study aimed to better understand what factors influence recurrence fears and psychological adaptation to the physical, emotional, and role changes associated with the diagnosis. We utilized social-cognitive processing theory, which posits that successful processing of difficult life events results from active assimilation of the experience into one’s “world view” [26]. Cognitive processing strategies include reappraising the experience to reduce threat and enhance perceived control. We focused on three cognitive strategies that have been associated with distress among cancer patients: positive reappraisal [27], coping appraisals that lift confidence [28–30], and self-esteem appraisals [31, 32]. We proposed that these cognitive factors would mediate the relationship between fear of recurrence and psychological distress. As fear increases, patients may have difficulty reappraising the situation, feel less efficacious in coping, and experience decreased self-esteem, and distress may persist.

While some cognitive processing is done individually, the social network plays an important role by either assisting or interfering with effective adaptation [26]. Patients may hold back from sharing concerns, and family and friends may minimize concerns in order to protect the other person from the potential upset of discussing the cancer [33]. These behaviors predict poorer adjustment and persisting fears [32–34]. We focused on two social factors: holding back from sharing concerns and unsupportive family and friend responses. As fear increases, patients may hold back or family and friends may prove unsupportive, and distress may persist.

The current study had two aims: 1) to characterize, using a standardized measure, recurrence fears among women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancer; 2) to evaluate a model explaining how fear of recurrence predicts depressive symptoms and cancer-specific distress. We included variables linked to recurrence fears in prior research, such as age [21–24], metastatic disease [25], and physical impairment [12, 19]. We predicted that cognitive (positive reappraisal, coping efficacy, and self-esteem) and social (holding back from sharing cancer concerns and negative responses from family and friends) processes would mediate the relationship between recurrence fears and distress. We evaluated depressive symptoms and cancer-specific distress separately because prior research has found different predictors between cancer-specific distress and depression [35] and different outcomes for these variables in intervention work [27].

METHOD

Participants and Procedures

The study had a cross sectional design. The sample consisted of women who were newly diagnosed with primary gynecological cancer (ovarian, endometrial, cervical, vulvar, fallopian tube, or uterine cancer) and undergoing active medical treatment at seven hospitals in the northeastern US. They were enrolled in a randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a Coping and Communication-Enhancing Intervention versus a Supportive Counseling Intervention (SC) and Usual Care (UC) (Manne et al., unpublished data). Study inclusion criteria were: age 18 years or older; diagnosed with the cancer within the past six months, a Karnofsky Performance Status of 80 or above or an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score of 0 or 1; lived within a two-hour commuting distance from the recruitment center; English speaking; and no hearing impairment.

Eligible women were identified and contacted either in person or by phone by the research assistant after a letter describing the study was sent. Participants were approached and consented to the study within six months of diagnosis. Participants signed an informed consent document approved by an Institutional Review Board. The baseline survey was mailed to participants’ homes with a stamped return envelope and participants were able to complete the survey on their own time. Participants were paid $15 for the survey.

Of the first 451 patients approached, 150 agreed (33%) and are included here. The most common reasons for refusal were that they perceived that they would not benefit (12.6%) or felt too overwhelmed to participate (8.9%). Comparisons between study participants and refusers indicated that participants were younger (t (449) = 3.6, p < .001, Mparticipants = 55.8, Mrefusers = 59.6 years). Acceptance rates were significantly higher at two sites where the nurse practitioner screened patients to identify those eligible (87%, 78%, respectively compared to an average 30% across the other 5 sites). There were no differences with regard to stage of disease and race/ethnicity.

Measures

Outcome Measures

Depressive symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory [36] is a 21-item scale used to assess depressive symptomatology. Scores range from 0–63 with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression. Internal consistency in the present sample was 0.81.

Cancer-Specific Distress

The Impact of Events Scale [37] is a 15-item measure of the frequency and severity of intrusive thoughts, worries and feelings about cancer, avoidance, and numbing. Scores range from 0–75 with higher scores indicating greater distress. Internal consistency was 0.88.

Fear of Recurrence

The Concerns about Recurrence Scale (CARS;38) is a 25- item measure of the extent and nature of fear of cancer recurrence. Its four domains are worries about 1) health (11 items), 2) womanhood (7 items), 3) role (6 items), and 4) death (2 items). Item scores range from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) to indicate the degree of worry. The mean is calculated to measure total fear. The total ranges from 0–4 with higher scores indicating greater fear of recurrence. In the present study, internal consistency was 0.95 for total scale.

Cognitive processes

Positive Reappraisal

The 4-item positive reappraisal subscale from the COPE was used [39]. This assesses efforts to positively change beliefs about the cancer experience. Scores range from 4–16 with higher score indicating greater use of positive reappraisal. Internal consistency was 0.87.

Cancer-specific coping efficacy

A 17-item scale was developed for this study to assess on a 5-point Likert scale confidence in coping skills relevant to managing common challenges of gynecological cancer (e.g., confidence in the ability to express and identify support needs). Scores range from 17–85 with higher scores indicating greater confidence in coping skills. Internal consistency was 0.93.

Self-Esteem

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale [40] measured self-acceptance and has 10-items on a Guttman 4-point continuum from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. Scores range from 10–40 with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem. Internal consistency was 0.79.

Social processes

Holding back

The degree to which the participant held back from talking about 12 cancer-related concerns was adapted from Porter and colleagues [34]. Scores range from 0–5 with higher scores indicating a greater degree of holding back. Internal consistency was 0.95.

Family/friend unsupportive behaviors [26]

This 13-item measure assesses critical responses such as “Criticized the way you handled your illness and its treatment” and avoidant responses such as “Seemed uncomfortable talking with you about your illness”. Items are rated on a 4-point response scale. Scores range from 13–52 with higher scores indicating greater critical responses from family/friends. Internal consistency was 0.90.

Demographic/Medical variables

Demographics

Demographic data was obtained on the baseline survey and included age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, and income.

Physical impairment

Physical impairment was assessed with the 26-item functional status subscale of the Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) [41]. Participants rated difficulty during the past month from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Scores range from 0–104 with higher scores indicating greater impairment. Internal consistency was 0.92.

Symptom severity

Participants rated 11 treatment-related symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, neurosensory) on the degree of severity from none (0) to severe (2). The sum was calculated to assess overall symptoms severity (Range = 0–22) with higher scores indicating greater symptoms severity.

Medical Chart

Medical chart review was used to capture metastatic status [yes/no], primary cancer diagnosis, disease stage, ECOG, tumor debulking [yes/no], status of debulking (optimal/suboptimal), CA-125 level, and psychotropic medication usage.

Concurrent Medical Conditions

Participants indicated additional medical conditions on the baseline survey.

Statistical Analysis

To address our first aim and characterize fear of recurrence within the population, we calculated means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for all study variables. We also conducted independent groups t-tests to compare this sample of gynecological cancer patients to a sample of breast cancer patients. We conducted Pearson zero-order correlations and independent t-tests to examine the relationships between fear of recurrence and all demographic and medical variables. We also conducted Pearson zero-order correlations and independent t-tests to examine the relationships between the outcome variables (depression and cancer-specific distress) and all demographic and medical variables.

To address our second aim, we first estimated two separate path models using AMOS (version 19) to assess overall model fit of the social-cognitive processing model predicting depression and cancer-specific distress. The models included fear of recurrence, as well as the social-cognitive variables, as a set of mediators of the relationships between the three demographic/medical variables (age, metastatic status, and functional impairment) and the outcome variables (depression and distress). To examine the degree to which the social and cognitive variables mediated the fear and depression and the fear and cancer-specific distress relationships, we utilized a multiple mediator regression approach in SPSS as outlined by Preacher and Hayes [42]. This approach estimates the degree to which a set of mediating variables together can account for an association between a predictor variable and an outcome. The method provides estimates of the total, direct, and indirect effects of a predictor variable on an outcome. In addition, it provides estimates of the extent to which each individual mediator shows indirect effects when controlling for the presence of the other mediators in the model. It utilizes boot-strapping to generate confidence intervals for the overall indirect effect as well as the unique (i.e., partial) indirect effects for each mediator.

RESULTS

Demographic and Medical Data

The sample consisted of 150 participants. The sample was mostly Caucasian (84%) and married (68%). The average age was 55.8 years (range 24–72 years). The majority of the sample was diagnosed with ovarian cancer (63%) and approximately half (51%) had metastatic cancer and were diagnosed with stage III disease (48%). Detailed description of demographic and medical data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Medical Data for Study Participants [N=150]

| Variable | M | SD | Range | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 55.83 | 9.79 | 24–78 | ||

| Household income [$] | 154,640 | 32,3367 | 2,000–750,000,000 | ||

| Race | |||||

| Caucasian | 126 | 84 | |||

| African American | 15 | 10 | |||

| Asian/Pacific Island | 4 | 3 | |||

| Hispanic | 2 | 1 | |||

| Unspecified | 3 | 2 | |||

| Education Level | |||||

| < High school | 2 | 1 | |||

| High school graduate | 23 | 15 | |||

| Trade or Business school | 3 | 2 | |||

| Some college | 23 | 15 | |||

| College graduate | 30 | 20 | |||

| Some graduate school | 14 | 9 | |||

| Graduate degree | 55 | 37 | |||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 102 | 68 | |||

| Unmarried | 44 | 29 | |||

| Data missing | 4 | 3 | |||

| Primary Cancer | |||||

| Ovarian | 95 | 63 | |||

| Endometrial | 16 | 11 | |||

| Uterine | 16 | 11 | |||

| Fallopian | 12 | 8 | |||

| Cervical | 4 | 2 | |||

| Peritoneal | 3 | 2 | |||

| More than one | 4 | 2 | |||

| Stage | |||||

| I | 25 | 17 | |||

| II | 19 | 13 | |||

| III | 72 | 48 | |||

| IV | 31 | 20 | |||

| Data missing | 3 | 2 | |||

| Metastatic Cancer | |||||

| Yes | 77 | 51 | |||

| No | 73 | 49 | |||

| Concurrent Medical Problems | |||||

| None | 23 | 15 | |||

| One | 45 | 30 | |||

| Two | 44 | 29 | |||

| Three or More | 38 | 25 | |||

| Tumor Debulking | |||||

| Yes | 83 | 55 | |||

| No | 49 | 33 | |||

| Data missing | 18 | 12 | |||

| Tumor Debulking, if yes | |||||

| Optimal | 71 | 92 | |||

| Suboptimal | 6 | 8 | |||

| Psych Medication | |||||

| Yes | 96 | 64 | |||

| No | 52 | 35 | |||

| Data missing | 2 | 1 | |||

| CA-125 Level | 241 | 936 | 0–7788 | ||

| Functional Impairment [CARES] | 31.88 | 18.38 | 1–84 | ||

Note. CARES = Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System

Characterization and Correlates of Fears of Recurrence

The overall fear of recurrence was in the mild-to-moderate range (M= 1.92; SD = 0.94). Moderate-to-high recurrence fears were reported by 47% of the participants. On the specific subscales, health (M= 2.35; SD = 1.04) and death (M= 2.84; SD = 1.32) worries were in the moderate-to-high range. Role (M= 1.86; SD = 0.99) and womanhood (M= 1.09; SD = 1.07) worries were in the mild-to-moderate range. Participants’ fear of recurrence on the specific health, womanhood, role, and death subscales were significantly higher when compared to data on recurrence fears among breast cancer patients [38] (p < .001 on all subscales). There were no differences in recurrence fears between patients in this sample whose primary diagnosis was ovarian cancer and patients with other types of gynecologic cancer.

We examined correlations between demographic (age, race/ethnicity, education, income, and marital status) and medical (primary diagnosis, disease stage, metastatic status, ECOG, CA-125 level, concurrent medical conditions, tumor debulking, and psychotropic medication use) variables and recurrence fears. Younger participants reported significantly greater recurrence fears (r = −.252, p < .01). On specific subscales, younger participants reported significantly greater womanhood (r = −.364, p =<.001) and role (r = −.260, p < .01) worries, but not health and death worries. There were no significant differences based on race/ethnicity for total recurrence fears. However, Caucasians reported significantly greater death worries than non-Caucasians, t (146) = 4.24, p < .001. Participants with more functional impairment reported significantly greater total recurrence fears (r = .244, p < .01) and worries about health (r = .175, p < .05), womanhood (r = .271, p < .01), and roles (r = .280, p < .01). Other than age and functional impairment, no additional demographic or medical variables were significantly correlated with total recurrence fears.

We examined correlations between demographic (age, race/ethnicity, education, income, and marital status) and medical (primary diagnosis, disease stage, metastatic status, ECOG, CA-125 level, concurrent medical conditions, tumor debulking, and psychotropic medication use) variables and the outcome variables (depression and cancer-specific distress). Younger participants reported significantly greater depression (r = −.187, p < .05) and cancer-specific distress (r = −.334, p < .001). Participants with greater functional impairment reported greater depression (r = .498, p < .001) and cancer-specific distress (r = .285, p < .01). No additional demographic or medical variables were significantly related to depression or cancer-specific distress.

Finally, we examined whether there were different correlates of recurrence fear between ovarian and non-ovarian patients. The only difference that emerged was that functional impairment was significantly related to recurrence fears for ovarian cancer patients (r = .329, p < .01), but the relationship was not significant for non-ovarian patients (r = −.001, p = .993). Further analyses revealed that ovarian cancer patients had significantly greater functional impairment than non-ovarian patients, t(145) = 2.75, p < .01.

For further analyses, we only included in the models variables that were significantly related to total recurrence fears or the outcome variables (age and functional impairment) and variables found to be related to recurrence fears in prior studies (age, metastatic status, and functional impairment) [12, 19, 22–25].

Evaluation of the Mediational Models

Preliminary Analyses

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 2. Total fear of recurrence was significantly related to all variables, except metastatic status.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for the Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression | |||||||||||

| 2. Cancer-Specific Distress | .56** | ||||||||||

| 3. Holding Back | .49** | .51** | |||||||||

| 4. Negative Response Family/Friends | .35** | .14 | .29** | ||||||||

| 5. Coping Efficacy | −.45** | −.35** | −.55** | −.10 | |||||||

| 6. Positive Reappraisal | −.25** | −.11 | −.26** | .02 | .41** | ||||||

| 7. Self-Esteem | −.59** | −.30** | −.34** | −.35** | .43** | .08 | |||||

| 8. Fear of Recurrence | .48** | .58** | .49** | .22** | −.41** | −.21** | −.40** | ||||

| 9. Age | −.19* | −.33** | −.18* | −.14 | .02 | −.13 | .21* | −.25** | |||

| 10. Metastatic status | −.04 | .01 | −.01 | −.06 | −.06 | −.06 | −.02 | .08 | .10 | ||

| 11. Functional Impairment | .50** | .28** | .24** | .28** | −.19* | −.05 | −.33** | .24** | −.07 | .07 | |

| M | 13.15 | 29.06 | 1.96 | 16.83 | 54.84 | 11.33 | 21.71 | 1.92 | 55.76 | 0.51 | 31.89 |

| SD | 7.03 | 15.56 | 1.27 | 5.28 | 12.22 | 3.76 | 4.70 | .94 | 9.76 | 0.50 | 18.19 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01. N = 150

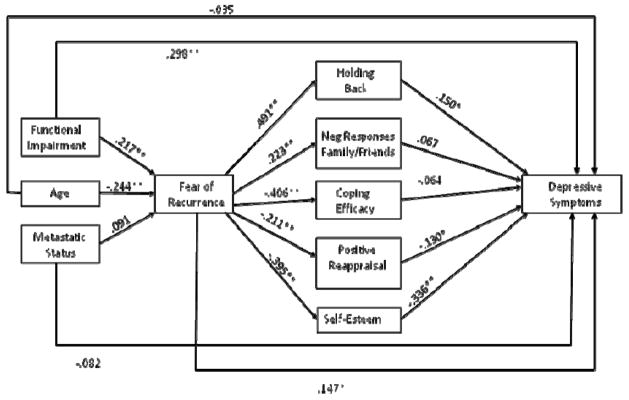

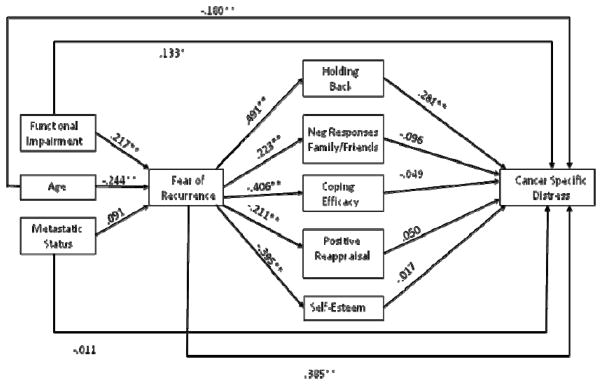

We examined two path models predicting depression and cancer-specific distress respectively to evaluate the overall fit of the social-cognitive processing models of depression and cancer-specific distress. These models are presented in Figures 1 and 2. Figures 1 and 2 present the standardized path coefficients. Although not included in the figures, age, metastatic status, and functional impairment were allowed to correlate. The residuals for the social and cognitive variables were also allowed to correlate. Model fit for both outcomes was acceptable: For the model predicting depression, the chi-square with df = 15 was χ2 = 28.95, p < .05, CFI = .96, and RMSEA = .079; and for the model predicting cancer-specific distress, χ2(15) = 28.95, p < .05, CFI = .95, and RMSEA = .079.

Figure 1.

Social-Cognitive Model of Depressive Symptoms

Note. * p < .05, ** p < .01

Figure 2.

Social-Cognitive Model of Cancer-Specific Distress

Note. * p < .05, ** p < .01

Model predicting depressive symptoms

Mediation analyses were conducted utilizing the Preacher and Hayes [42] multiple mediator regression approach described above to determine the extent to which a set of mediators together mediate the association between a predictor and an outcome variable. The initial mediation analyses examined the extent to which the impact of each demographic and medical variable (age, metastatic status, and functional impairment) on depressive symptoms were mediated by recurrence fears and social and cognitive variables. The unstandardized regression coefficients for the total, direct, and indirect effects are presented in Table 3. The total effect of age on depression was statistically significant (b = −.134, p < .05). When the proposed mediators (fear of recurrence, positive reappraisal, coping efficacy, self-esteem, holding back and unsupportive responses) were included in the model the direct effect was not statistically significant (b = −.023) and the indirect effect was statistically significant (b = −.111, p < .01), indicating that the set of mediators fully mediated the relationship between age and depression. The set of mediators accounted for 83% of the age and depression relationship. Looking at the individual mediators, holding back (b = −.022, 95% CI: −.065 to −.004), self-esteem (b = −.058, CI: −.125 to −.018), and fear of recurrence (b = −.028, CI: −.084 to −.003) accounted for a statistically significant portion of the mediational effect.

Table 3.

Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects of Demographic, and Medical Variables on Depressive Symptoms and Cancer-Specific Distress

| Predictor Variable | Predicting Depression | Predicting Cancer-Specific Distress | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Indirect 95%CI | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Indirect 95%CI | |

| Age | −.134* | −.023 | −.111** | −.21 to −.02 | −.522** | −.281** | −.241** | −.41 to −.08 |

| Functional Impairment | .191** | .108** | .083** | .04 to .13 | .236** | .106 | .130** | .03 to .25 |

| Metastatic Status | −.573 | −.892 | .319 | −1.28 to 2.12 | .391 | −.645 | 1.036 | −2.10 to 4.20 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01. Tabled values are unstandardized regression coefficients. The indirect effect is the total indirect effect treating fear of recurrence, holding back, negative responses from family and friends, coping efficacy, positive reappraisal, and self-esteem as mediators.

The relationship between functional impairment and depression was partially mediated by fear of recurrence and the social and cognitive variables. These variables accounted for 43% of the relationship between functional impairment and depression. In terms of individual mediators, holding back (b = .014, 95% CI: .002 to .037), self-esteem (b = .042, CI: .014 to .073), and recurrence fears (b = .013, CI: .001 to .039) had significant indirect effects and accounted for a significant portion of the mediational effect. Metastatic status was not a significant predictor of depression and the total, direct, and indirect effects were all non-significant and were omitted from Table 3.

We tested whether cognitive (positive reappraisal, coping efficacy, and self-esteem) and social variables (holding back and negative responses from family and friends) mediated the association between recurrence fears and depressive symptoms. The total effect of recurrence fears on depression was b = 3.579, se = .541, p < .01, the direct effect was b = 1.226, se = .540, p < .05, and the total indirect effect was b = 2.353, se = .431, p < .01 (CI: 1.375 to 3.420), indicating partial mediation. Table 4 presents the indirect effects and confidence intervals for each of the mediating variables. The social and cognitive variables account for approximately 66% of the association between recurrence fear and depression. Table 4 indicates that after controlling for the other social and cognitive variables, holding back (b = .642, CI: .066 to 1.402) and self-esteem (b = −1.145, CI: .596 to 1.876) both accounted for a statistically significant portion of the association between fear of recurrence and depression.

Table 4.

Indirect Effects of Social and Cognitive Variables Mediating the effect of Fear of Recurrence on Depressive Symptoms and Cancer-Specific Distress

| Mediators | Depression | Cancer-Specific Distress | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effect | Indirect 95%CI | Indirect Effect | Indirect 95%CI | |

| Total | 2.353** | 1.38 to 3.42 | 2.446** | .67 to 4.29 |

| Holding Back | .642* | .06 to 1.40 | 2.572** | 1.11 to 4.60 |

| Neg Resp Friends & Family | .203 | −.04 to .85 | −.255 | −.91 to .34 |

| Coping Efficacy | .182 | −.25 to .75 | .181 | −1.11 to 1.34 |

| Positive Reappraisal | .182 | −.02 to .57 | −.284 | −1.11 to .20 |

| Self-esteem | 1.145** | .60 to 1.88 | .231 | −.74 to 1.58 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01. Tabled values are unstandardized regression coefficients.

Model predicting cancer-specific distress

Parallel analyses were used for the model of cancer-specific distress. First we examined the degree to which the impact of each demographic and medical variable (age, metastatic status, and functional impairment) on distress were mediated by recurrence fears and social and cognitive variables. The unstandardized regression coefficients for the total, direct, and indirect effects of cancer-specific distress are presented in Table 3. There is evidence of partial mediation for the effect of age on cancer-specific distress, with the set of mediators (fear of recurrence and the social and cognitive variables) accounting for 46% of the association between age and cancer-specific distress. Holding back (b = −.085, CI: −.190 to −.014) and fear of recurrence (b = −.157, CI: −.294 to −.059) accounted for a statistically significant portion of the relationship between age and cancer-specific distress after controlling for the other social and cognitive variables.

There was evidence of partial mediation for the effect of functional impairment on cancer-specific distress, with the mediators accounting for 55% of the association between functional impairment and cancer-specific distress. After controlling for the effects of the other variables in the model, holding back (b = .062, CI: .016 to .134), and fear of recurrence (b = .086, CI: .024 to .179) had statistically significant indirect effects. Metastatic status was not a significant predictor and the total, direct, and indirect effects were all non-significant and omitted from Table 3.

Finally, we examined the degree to which the association between fear of recurrence and distress was mediated by the social and cognitive variables. The total effect of fear of recurrence on cancer-specific distress was b = 9.588, se = 1.112, p < .01, the direct effect was b = 7.143, se = 1.282, p < .01, and the total indirect effect was b = 2.446, se = .799, p < .01 (CI: .674 to 4.290), indicating partial mediation. Table 4 presents the indirect effects and confidence intervals. The social and cognitive variables accounted for 26% of the association between fear of recurrence and cancer-specific distress. Only holding back accounted for a statistically significant portion of the association between fear of recurrence and cancer-specific distress (b = 2.572, CI: 1.108 to 4.605) after controlling for the effects of the other variables in the model.

DISCUSSION

Fear of recurrence is a significant concern among women with gynecologic cancer, with almost half of the participants reporting moderate-to-high fear. Our finding is higher than studies of long-term (>5 years) ovarian cancer survivors [18], suggesting that recurrence fears may be greater closer to diagnosis. As time passes without evidence of recurrence, fears understandably diminish. Participants reported the greatest fears in regard to death and health. Based on the physical impact of treatment [1–3] and the relatively poor prognosis for many types of gynecologic cancer [16], the findings are not surprising. Fear among this sample for all domains was higher than for women with breast cancer [38], thus emphasizing the importance of fear among this cancer group. While there are differences in prognosis and symptoms across the different types of gynecologic cancer, there were not differences in recurrence fears between patients diagnosed with ovarian cancer and patients diagnosed with other types of gynecologic cancer. The only difference that emerged was that greater functional impairment was associated with greater fears only for ovarian cancer patients. This may be explained by ovarian cancer patients having significantly greater impairment. Impairment may only influence recurrence fears when it is at a high level. However, the majority of the sample was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and further examination with a larger sample of non-ovarian gynecologic cancers is needed.

Consistent with previous research, younger age was associated with greater recurrence fears [19, 21–24], but only in regard to womanhood and role worries, not health and death worries. Similar patterns occur in women with breast cancer [24, 38]. Due to normative life expectations, younger women may place more emphasis on body image, sexuality, and childrearing and employment roles, and be more distressed by the threat of recurrence on those areas. Another interesting finding was that Caucasians reported more death worries than non-Caucasians. It is possible that factors that were not assessed, such as spirituality/faith, played a role. Given that the majority of the sample was Caucasian, the finding cannot be generalized, and further examination is needed.

Being diagnosed at an early stage did not buffer against recurrence fears, consistent with research on early and advanced stage cancer patients [19] and patterns found in breast cancer [38]. Lower CA-125 levels and positive surgical outcomes, such as optimal tumor debulking, did not predict recurrence fears. Similarly, metastatic status was not significantly related to recurrence fears. A possible explanation is that women may place less emphasis on these medical factors, be less likely to understand their relevance, or choose not to focus on them. In contrast, physical symptoms may be interpreted as worsening disease, thus increasing fears.

Our study supported a social-cognitive model of recurrence fears and psychological distress, consistent with past research [43]. Self-esteem played a significant role in the relationship between recurrence fears and depression. Increased fear of recurrence was related to decreased self-esteem, which was related to increased depression. Persistent recurrence fears may exacerbate negative beliefs about self. Cognitive efforts to enhance self-esteem have been suggested to facilitate adaptation to difficult events, such as cancer [31]. When faced with recurrence fears, utilizing cognitive resources to process the fears within a self-enhancing framework may reduce the negative impact. By focusing on strengths and positive qualities, women may gain enhanced control over fears, and be less susceptible to depression.

In terms of social resources, holding back played a significant role in the relationship between recurrence fears and both depression and cancer-specific distress. Increased fear of recurrence was related to more holding back, which was related to increased cancer-specific distress. Sharing concerns may facilitate adaptation by providing an opportunity to process the fear, challenge negative beliefs, and enhance self-worth. Prior research has indicated that social constraints to talking about cancer inhibited processing and increased distress [43]. While the intention of holding back concerns is often to protect others from shared distress [44], the result is often paradoxical [34]. Younger age and greater functional impairment may hinder social and cognitive resources, thus reducing opportunities for successful processing of the cancer experiences. The models for depression and cancer-specific distress were very similar, suggesting that the social and cognitive resources may play similar roles in psychological adaptation.

There were some postulated factors that did not have unique mediating effects in the model, for instance positive reappraisal and coping efficacy. Patients may be able to positively reappraise the situation and glean meaning, but this does not buffer the impact of recurrence fears. Similarly, a sense of overall coping efficacy may not translate into efficacy in coping specifically with recurrence fears. Negative responses from family and friends also did not mediate the relationship. Positive social support may play a greater role.

A strength of the study was the use of a standardized scale that enabled better assessment of the construct and comparison to other patients. Additionally, we included different types of gynecologic cancer and newly diagnosed women. Finally, we used a social-cognitive processing model to examine the associations between recurrence fears and distress. There are several limitations. First, the study is cross-sectional, and the direction of causation among the variables cannot be determined. For example, it could be argued that psychological distress causes patients to hold back more, rather than holding back leading to increased distress. Second, many variables were assessed by patient self-report, which may be influenced by dispositional characteristics not included in the model. Third, some patients may not be aware of aspects of their medical status (e.g., tumor debulking), and becoming aware could impact their fears. There are limits to generalizability of our findings. As the majority of sample was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, larger samples of other types of gynecologic cancers would clarify whether there are differences between different cancers. Additionally, the cohort was mostly Caucasian, well-educated, and middle-class. Finally, the sample consisted of women who agreed to participate in a randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of therapy interventions and there may be certain psychological factors that differentiate gynecologic cancer patients who chose to participate that we were not able to compare with women who chose not to participate. Those who chose to participate did tend to be younger. It is possible that the age differences that emerged in regard to fear of recurrence, depression, and cancer-specific distress may reflect a tendency for the sample to be younger.

Our results provide support for the role of cognitive and social resources in the processing of recurrence fears. These findings can assist medical providers in identifying patients who may be at risk of distress and benefit from support services to facilitate psychological adaptation, such as younger and more impaired women. Women with gynecologic cancer may benefit from psychosocial interventions aimed at enhancing social and cognitive resources to help gain a sense of control over fears through self-enhancing cognitive strategies and teaching women ways to share worries with supportive friends and family.

Highlights.

Fear of recurrence is significant among women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancers

Younger and more physically impaired women have greater recurrence fears

Social and cognitive factors impact the relationship between recurrence fears and psychological distress

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Project Managers Tina Gajda, Sara Worhach, Shira Hichenberg, and Research Study Assistants Joanna Crincoli, Katie O’Neill, Arielle Schwerda, Kristen Sorice, and Sloan Harrison, as well as the study participants, their oncologists, and the clinical teams at The Cancer Institute of New Jersey, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson University, Morristown Medical Center, and Cooper University Hospital. We also wish to thank Brian Slomovitz, MD. This work was funded by NIH grant R01 CA085566 to Sharon Manne, Ph.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors of the manuscript declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Shannon B. Myers, The Cancer Institute of New Jersey

Sharon L Manne, The Cancer Institute of New Jersey

David W. Kissane, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Melissa Ozga, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Deborah A. Kashy, Michigan State University

Stephen Rubin, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Carolyn Heckman, Fox Chase Cancer Center

Norman Rosenblum, Thomas Jefferson University

Mark Morgan, Fox Chase Cancer Center

John J. Graff, The Cancer Institute of New Jersey

References

- 1.Anderson NJ, Hacker ED. Fatigue in women receiving intraperitoneal chemotherapy for ovarian cancer: A review of contributing factors. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008 Jun;12:445–54. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.445-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonçalves V. Long-term quality of life in gynecological cancer survivors. Curr Opin Obstet & Gynecol. 2010 Feb;22:30–35. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328332e626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nout RA, Putter H, Jürgenliemk-Schulz IM, Jobsen JJ, Lutgens LC, van der Steen-Banasik EM, et al. Quality of life after pelvic radiotherapy or vaginal brachytherapy for endometrial cancer: First results of the randomized PORTEC-2 trial. J of Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3547–3556. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodurka-Bevers D, Basen-Engquist K, Carmack CL, Fitzgerald MA, Wolf JK, de Moor C, et al. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:302–308. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norton T, Manne S, Rubin S, Carlson J, Hernandez E, Edelson MI, et al. Prevalence and predictors of psychological distress among women with ovarian cancer. J ClinOncol. 2004;22:919–926. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Orazio LM, Meyerowitz BE, Stone PJ, Felix J, Muderspach LI. Psychosocial adjustment among low-income Latina cervical cancer patients. J Psych Oncol. 2011;29:515–533. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.599363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornblith AB, Powell M, Regan MM, Bennett S, Krasner C, Moy B, et al. Long-term psychosocial adjustment of older vs younger survivors of breast and endometrial cancer. Psychoncol. 2007;16:895–903. doi: 10.1002/pon.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steginga SK, Dunn J. Women’s experiences following treatment for gynecologic cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1997;24:1403–1408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manne S, Rini C, Rubin S, Rosenblum N, Bergman C, Edelson M, et al. Long-term trajectories of psychological adaptation among women diagnosed with gynecological cancers. Psychosom Med. 2008;76:1034–1045. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817b935d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker F, Denniston M, Smith T, West MM. Adult cancer survivors: How are they faring? Cancer. 2005;104:2565–2576. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor TR, Huntey ED, Sween J, Makambi K, Mellman TA, Williams CD, et al. An exploratory analysis of fear of recurrence among African-American breast cancer survivors. Intern J Beh Med. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9183-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart SL, Latini SM, Cowan JE, Carroll PR. Fear of recurrence, treatment satisfaction, and quality of life after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Supp Care Cancer. 2008;16:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llewellyn CD, Weinman J, McGurk M, Humphris G. Can we predict which head and neck cancer survivors develop fears of recurrence? J Psychosom Res. 2008;65:525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black EK, White CA. Fear of recurrence, sense of coherence and posttraumatic stress disorder in haemotological cancer survivors. Psychoncol. 2005;14:510–515. doi: 10.1002/pon.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta SS, Lubeck DP, Pasta DJ, Litwin MS. Fear of cancer recurrence in patients undergoing definitive treatment for prostate cancer: Results from CaPSURE. J Urolog. 2003;170:1931–1933. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091993.73842.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Cancer Society. [Accessed on April 23 2012];Cancer Facts and Figures. 2012 Available at http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-031941.pdf.

- 17.Shinn EH, Carmack-Taylor CL, Kilgore K, Valentine A, Bodurka DC, Kavanagh J, et al. Associations with worry about dying and hopelessness in ambulatory ovarian cancer patients. Palliat and Supp Care. 2009;7:299–306. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wenzel L, Donnelly J, Fowler JM, Habbal R, Taylor TH, Aziz N, et al. Resilience, reflection, and residual stress in ovarian cancer survivorship: a gynecologic oncology group study. Psychoncol. 2002 Mar;11:142–153. doi: 10.1002/pon.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirabeau-Beale KL, Kornblith AB, Penson RT. Comparison of the quality of life of early and advanced stage ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Bradley SL, Rose SL, Anderson B. Cancer attributions, distress and health practices among gynecologic cancer survivors. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:972–980. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188402.95398.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matulonis UA, Kornblith A, Lee H, Bryan J, Gibson C, Wells C, et al. Long- term adjustment of early-stage ovarian cancer survivors. Intern J of Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:1183–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphris GM, Rogers S, McNally D, Lee-Jones C, Brown J, Vaughan D. Fear of recurrence and possible cases of anxiety and depression in orofacial cancer patients. Intern J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:486–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thewes B, Butow P, Bell ML, Beith J, Stuart-Harris R, Grossi M, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in young women with a history of early-stage breast cancer: A cross-sectional study of prevalence and association with health behaviors. Supp Care Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1371-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziner K, Sledge G, Bell C, Johns S, Miller K, Champion V. Predicting Fear of Breast Cancer Recurrence and Self-Efficacy in Survivors by Age at Diagnosis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:287–295. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.287-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Perez M, Schootman M, Aft RL, Gillanders WE, Jeffe DB. Correlates of fear of cancer recurrence in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res and Treat. 2011;130:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1551-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lepore SJ. A social-cognitive processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer. In: Baum A, Anderson BL, editors. Psychosocial interventions for cancer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manne SL, Winkel G, Rubin S, Edelson M, Rosenblum N, Bergman C, et al. Mediators of a coping and communication- enhancing intervention and a supportive counseling intervention on depressive symptoms among women diagnosed with gynecological cancers. J Consul and Clin Psych. 2008;76:1034–45. doi: 10.1037/a0014071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGinty HL, Goldenberg JL, Jacobsen PB. Relationship of threat appraisal with coping appraisal to fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Psychoncol. 2010;21:203–210. doi: 10.1002/pon.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosher CE, DuHamel KD, Egert J, Smith MY. Self-efficacy for coping with cancer in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: Associations with barriers to pain management and distress. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:227–234. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181bed0e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Philip EJ, Merluzzi TV, Zhang Z, Heitzmann CA. Depression and cancer survivorship: Importance of coping self-efficacy in post-treatment survivors. Psychoncol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/pon.3088. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor SE. Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation. Amer Psychol. 1983 Nov;:1161–1173. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norton T, Manne S, Rubin S, Hernandez E, Carlson J, Bergman C, et al. Ovarian cancer patients’ psychological distress: The role of physical impairment, perceived unsupportive family and friend behaviors, perceived control, and self-esteem. Health Psych. 2005;24:143–152. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manne S, Taylor K, Dougherty J, Kemeny N. Supportive and negative responses in the partner relationship: Their association with psychological adjustment among individuals with cancer. J Behav Med. 1997;20:101–125. doi: 10.1023/a:1025574626454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Hurwitz H, Faber M. Disclosure between patients with gastrointestinal cancer and their spouses. Psychoncol. 2005;14:1030–1042. doi: 10.1002/pon.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Mattes ML, Trehan S, Robinson CB, Tewfik F, et al. Adjusting to life after treatment: Distress and quality of life following treatment for breast cancer. Brit J Cancer. 2007;97:1625–1631. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck AT, Beamesderfer A. Assessment of depression: the depression inventory. Mod Probl Pharmacopsych. 1974;7:151–169. doi: 10.1159/000395074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vickberg SM. The concerns about recurrence scale (CARS): a systematic measure of women’s fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:16–24. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2501_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psych. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Vol. 1965 Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schag C, Heinrich R. CARES: Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System. Santa Monica, CA: Cares Consultants; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Beh Res Meth. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cordova MJ, Cunningham LL, Carlson CR, Anrykowsi MA. Social constraints, cognitive processing, and adjustment to breast cancer. J Consul Clin Psych. 2001;69:706–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okuyma T, Endo C, Seto T, Kato M, Seki N, Akechi T, et al. Cancer patients’ reluctance to disclose their emotional distress to their physicians: A study of Japanese patients with lung cancer. Psychoncol. 2008;17:460–65. doi: 10.1002/pon.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]