Abstract

The insulin and insulin like growth factor (IGF) signaling systems are implicated in breast cancer biology. Thus, disrupting IGF/insulin signaling has been shown to have promise in a number of preclinical models. However, human clinical trials have been less promising. Despite evidence of some activity in early phase trials, randomized phase III studies have thus far been unable to show a benefit of blocking IGF signaling in combination with conventional strategies. In breast cancer, combination anti IGF/insulin signaling agents with hormone therapy has not yet proven to have benefit. This inability to translate the preclinical findings into useful clinical strategies calls attention to the need for a deeper understanding of this complex pathway. Development of predictive biomarkers and optimal inhibitory strategies of the IGF/insulin system should yield better clinical strategies. Furthermore, unraveling the interaction between the IGF/insulin pathway and other critical signaling pathways in breast cancer biology, namely estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathways, provides additional new concepts in designing combination therapies. In this review, we will briefly summarize the current strategies targeting the IGF/insulin system, discuss the possible reasons of success or failure of the existing therapies, and provide potential future direction for research and clinical trials.

Keywords: Breast cancer, insulin-like growth factor, type I receptor IGF receptor, insulin receptor, predictive biomarkers

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death among women in the US. In 2012, about 226,870 breast cancer cases will be newly diagnosed and about 39,510 women will die from this disease (www.cancer.org). In the past decade the death rate from breast cancer is decreasing, even though breast cancer incidence remains high. The wider use of adjuvant therapy for operable breast cancer partially accounts for this improvement. Targeting the estrogen receptor-α has proven to be one of the most useful methods to decrease breast cancer death mortality [1]. Targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her2) with trastuzumab (Herceptin®) has also been an important advance [2, 3]. The clinical success of targeting receptors critical in breast cancer biology has underlined the importance of identifying and understanding the regulatory pathways involved in breast cancer growth and metastases. Furthermore, with the awareness of the complexity and heterogeneity of breast cancer [4], developing additional targeted therapies is critical to further improve breast cancer outcomes.

The insulin-like growth factor/insulin (IGF/insulin) system possesses potent mitogenic and pro-migratory properties and has been extensively implicated in many malignancies including breast cancer [5–7]. The type I insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR) is a component of the complex IGF/insulin signaling network. IGF-IR has been shown to regulate cell metabolism, enhance transformation, stimulate proliferation, and promote metastasis in breast cancer [5, 6, 8–10]. Numerous lines of evidence suggest that blockade of the IGF/insulin signaling pathway inhibits growth and metastasis in multiple cancer types including breast cancer both in vitro and in vivo [8, 11–14]. Collectively, IGF-IR has been viewed as a potentially valuable target for breast cancer treatment.

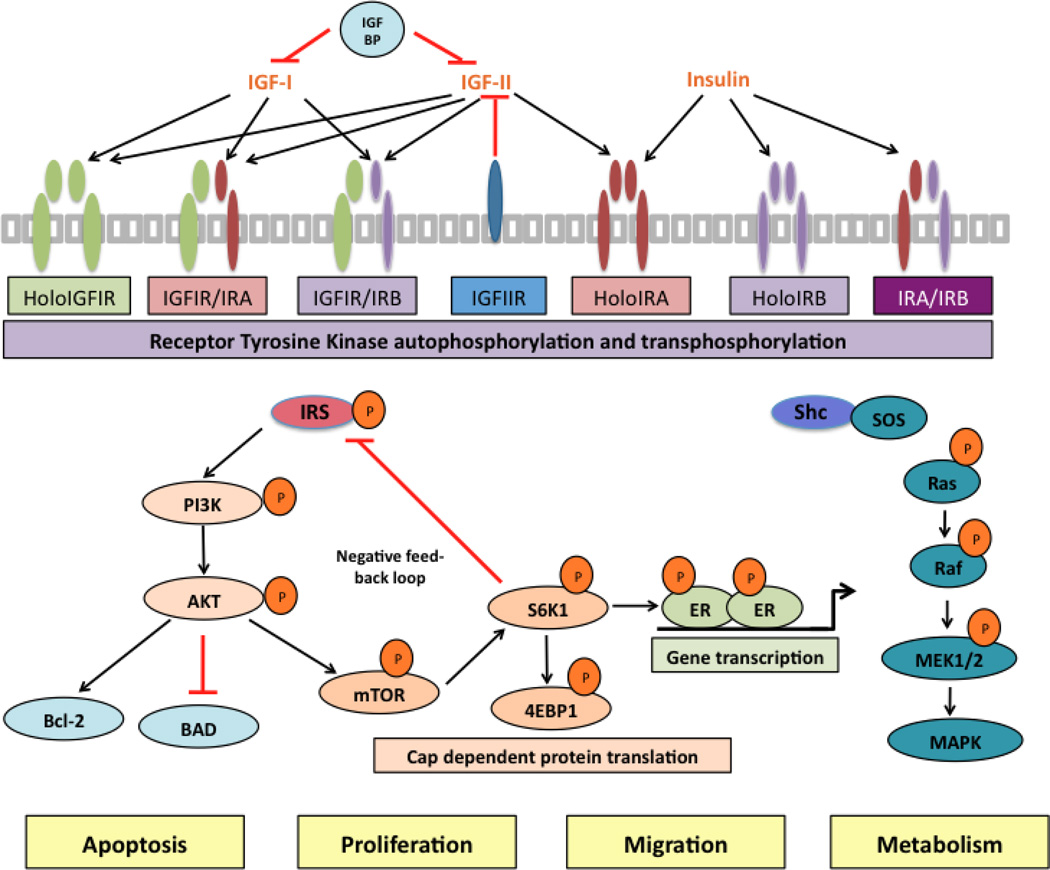

The IGF/insulin system consists of three ligands, IGF-I, IGF-II, and insulin; six ligand-binding proteins, IGFBP 1–6; and 2 transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors (RTK) genes the type I IGF receptor (IGF-IR) and the insulin receptor (IR). The receptor genes encode the α and β subunits of the protein. For a fully function receptor, the gene products must be dimerized with a partner. Thus, holo-receptors and hybrid receptors composed of half IGF-IR and half (IR) are capable of forming (Figure 1). These functional receptors are composed of two extracellular α subunits covalently linked to two intracellular β subunits, which contain the tyrosine kinase domains. Following ligand binding to the extracellular α subunits, the receptors undergo a conformational change resulting in activation of its tyrosine kinase activity and trans-phosphorylation of the intracellular β subunits. The activated receptors then recruit and phosphorylate adaptor proteins including insulin receptor substrates (IRS 1–6) and Shc. This couples the initial ligand-binding event and further triggers multiple downstream signaling pathways, including phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase (PI3K) and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). These secondary messenger molecules result in stimulation of specific cellular functions, such as proliferation, apoptosis, metastasis, metabolism, angiogenesis, and drug resistance [15, 16] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the IGF/insulin system. In the extracelluar environment, ligands IGF-I, IGF-II and insulin bind to distinct members of the IGF-IR and IR receptor family (as indicated by arrows). These transmemberane tetrameric receptors (three types of holo-receptors and three types of hybrid receptors) are composed of two extracelluar α-subunits, which function as binding domains; and membrane-spanning β-subunits, which possess tyrosine kinase activity. The bioactivity if IGF-I and IGF-II are negatively influenced by IGFBPs and IGF-IIR. Following the ligand binding and receptor activation, the phosphorylated adaptor proteins IRS and Shc provide a platform to initiate multiple downstream signaling pathways, namely PI3K/Akt and MAPK axis, ultimately influence tumor cell biology.

The insulin receptors are closely related and expressed as two isoforms, insulin receptor A (IR-A) and insulin receptor B (IR-B) with a 12 amino acid difference in exon 11 [17]. IR-B is the major form expressed in adults and has high affinity for insulin, while IR-A, which is abundantly expressed during fetal development and is commonly overexpressed in tumors [17], can transmit signals by binding to both insulin and IGF-II [18].

Since deregulation of cellular energy metabolism has been considered as an emerging hallmark of cancer [19], IR and its related metabolic syndromes have become another major focus in the breast cancer research and treatment field. Both obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus could lead to hyperinsulinemia, which has been reported to activate insulin receptors in normal breast epithelial cells [20]and in neoplastic tissues [21], increase the risk of developing breast cancer in patients with metabolic syndromes [22], promote metastatic progression, and associate with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients [23].

Strategies in targeting the IGF-I/insulin system

Blockade of ligand binding

In normal physiology, insulin is produced by pancreatic β-islet cells and arrives at target tissues through the blood circulation. For IGFs, the liver is the major producer for the circulating IGF-I, but normal tissue and tumor tissue can frequently secrete both IGF-I and IGF-II. Therefore, IGF-I and IGF-II could affect tumor biology via autocrine, paracine, and endocrine mechanisms. As mentioned above, IGF-IR and IR require ligand binding for receptor activation, thus reducing ligands levels becomes a reasonable and practical strategy to control the IGF-I/insulin signaling in neoplastic tissue. In normal physiology, reduction of insulin level is not practical because of the resultant metabolic effects on glucose control. In contrast, low levels of IGFs appear to be well tolerated in humans [24]. Since IGF-I is regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, via secretion of growth hormone, growth hormone-releasing hormone antagonists (e.g. JV-1–38 [25]) disrupting this pathway could be used to affect IGF-I levels. In addition, pegvisomant, a direct antagonist of the growth hormone receptor, has been developed to treat acromegaly and is also able to inhibit IGF-I levels in normal human subjects [26].

Another approach to reduce the levels of unbound ligands involves the use of monoclonal antibodies to neutralize extracellular IGFs. MEDI-573, a monoclonal antibody with high binding affinity for both IGFs selectively inhibits the activation of both the IGF1R and IR-A signaling pathways in vitro and in mouse models without disrupting glucose metabolism mediated by insulin and IR interaction [27]. MEDI-573 is now involved in several phase I clinical trials for different types of tumors (clinicaltrials.gov, identifier no. NCT01446159, NCT00816361). Another novel IGF ligand neutralizing antibody, BI 836845 (Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals), was recently shown to improve preclinical antitumor efficacy of rapamycin by suppressing IGFs’ bioactivity and inhibiting rapamycin-induced PI3K/AKT activation [28]. This drug is currently in a phase I clinical trial (NCT01317420).

IGFBPs regulate IGFs’ bioactivity by sequestering the peptides from binding to the receptors. Most of the IGFBPs can also act in an IGF-independent fashion. IGFBP3, in particular, has been shown to directly associate with cell surface and nuclear receptors thereby inducing antiproliferative effects and apoptosis (extensively reviewed in [29]). Thus, other approaches to reduce the ligands bioactivity may include recombinant IGFBPs, namely IGFBP3 [30, 31].

Targeting the receptors

As noted above, IGF/insulin system consists of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases and nearly all of them are targetable by either dominant negative constructs or pharmacological approaches. Traditionally, IR has not been considered the primary target due to its central role in glucose metabolism. However, accumulated data suggests IR-A may play important roles in breast cancer progression and survival [32, 33]. IR-A signaling has also been suggested as a possible mechanism of resistance to IGF-IR targeted therapies [34, 35]. Thus, developing safe therapies to control IR signaling is urgently needed. Indirectly targeting IR-A activation by downregulation of one of its ligands, IGF-II, has been shown to inhibit cancer cell growth. [35]. It is possible that ligand neutralization, as opposed to receptor inhibition, could result in less disruption of glucose metabolism.

In the past several years, major effort has been directed toward targeting IGF-IR. Anti-IGF-IR monoclonal antibodies have been developed and several trials using such antibodies as single agents or in combination with other antitumor drugs are in phase I/II clinical trials. The antibodies are designed specifically to bind the α subunit of IGF-IR with high affinity, thus they do not directly affect IR-A or IR-B. This class of drugs shares similar mechanisms of action by interfering with ligand binding to both holo-IGF-IR and hybrid receptors [36], and causing receptor endocytosis and subsequent degradation in the endosome thereby inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and metastasis [37].

Figitumumab (CP-751, 871, Pfizer), a fully human IgG2 α-IGF-IR monoclonal antibody, generated enthusiasm in a randomized phase II clinical study (NCT00147537). The study showed that combined figitumumab with carboplatin and paclitaxel enhanced response rate and prolonged progression-free survival and overall survival in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, Pfizer discontinued two phase III figitumumab clinical trials (NCT00673049, NCT00596830) due to a failure to confirm the promising phase II results and also observed substantial toxicity. Treatment of breast cancer patients with an aromatase inhibitor with or without figitumumab was studied but showed no benefit for the antibody [38]. AVE1642 (sanofi-aventis), a humanized IgG1 antibody, showed promising data in preclinical studies [39, 40] but failed in its phase II clinical trials in breast cancer patients (NCT00774878). One reason for the failure might be the lack of molecular markers that predict IGF-IR sensitive tumors.

Despite these failures, there are still several currently active trials primarily aimed to evaluate IGF-IR antibody as an adjuvant agent to other antitumor drugs in many types of cancer. Ganitumab (AMG 479, Amgen), a fully humanized IgG1 antibody, is being tested in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy, mTOR inhibitors, and hormonal therapies in various diseases including NSCLC, colorectal, pancreatic, ovarian, and breast cancer. Similar trials have been completed with the fully humanized IgG1 IGF-IR antibody cixutumumab (IMC-A12, Imclone).

Dalotuzumab (MK 0646, Merck), another humanized IgG1 antibody with promising preliminary profiles [41, 42], is currently being studied with aromatase inhibitors and the mTOR antagonist in advanced breast cancer.

The anti-IGF-IR monoclonal antibodies also share a common effect on the disruption of normal endocrine feedback systems that have implications for phase III clinical trials. One of the common side effects using the antibodies is disruption of the negative feedback of IGF-I on growth hormone secretion by the pituitary. Administration of the antibodies results in upregulation of the growth hormone serum levels resulting in increased circulating IGF levels, hyperglycemia, and hyperinsulinemia [43]. Since the antibodies do not block IR signaling, this could explain the failure to demonstrate clinical activity when only IGF-IR signaling is disrupted. Furthermore, subsequent development of refectory tumors in IGF-IR antibody treated patients might be due to both hyperinsulinemia [44] and high free IGF [44, 45]. Certainly, activation of IR signaling could initiate pro-survival signaling to blunt the effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy. A recent clinical trial for women with ER-positive breast cancer reported combined IGF-IR antibody with the aromatase inhibitor exemestane trended toward benefit only in patients with normal hemoglobin A1C levels [38], which is an indicator for insulin resistance. In IGF-IR antibody clinical trials design, patients with pre-existing insulin resistance may need to be excluded or have their hyperinsulinemia better controlled. It would be important to state that in preclinical rodent model systems the effect of hyperinsulinemia is not seen after exposure to IGF1R monoclonal antibodies as these antibodies do not have the same affinity for murine IGF1R. Adult rodents also do not have significant level of circulating IGF-II [46], thus mouse models might not accurately model the human endocrine milieu and the effects of endocrine disruptors designed to target human receptors.

Another major class of drugs to target IGF-IR activation is small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), which compete for the ATP binding site in the catalytic domain of the β subunit of IGF-IR and IR. Most TKIs show limited selectivity of IGF-IR over IR in vitro or in vivo [47, 48]. The high degree of homology of the intracellular β subunits of the IGF-IR and IR may account for this relative lack of selectivity of the TKIs. However, this dual targeting might have some benefits given the potential role for IR in cancer. Specifically, upregulated serum levels of insulin after IGF1R monoclonal antibody treatment might not have as much effect on the tumor if both IGF1R and IR are blocked by a TKI. Studies showed that these TKIs inhibited IGF-IR/IR phosphorylation and AKT activation, enhanced apoptosis, decreased in vitro cell proliferation, and tumor suppression in xenograft models [42, 49, 50]. A dual IGF-IR/IR dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor BMS-754807 (BMS) showed better antitumor efficacy in combination with hormonal therapies in hormone sensitive breast cancer model systems [50]. BMS-754807 and OSI-906 are two promising examples of small molecule inhibitors, being tested in several breast cancer clinical trials.

The cyclolignan picropodophyllin (AXL1717 or PPP, Axelar) is reported to specifically inhibit IGF-IR specific tyrosine kinase activity, although the exact mechanism is uncertain. The compound reportedly possesses both signal inhibitory properties and downregulates IGF-IR in vitro [51]. A phase I trial of this drug has been completed showing favorable safety and pharmacokinetics profiles of PPP in patients with advanced cancer (NCT01062620).

Other novel approaches to target IGF/insulin system at the receptor level include using small interfering RNA (siRNA) and microRNA to suppress IGF-IR expression and function. Recently, an interesting preclinical study showed that 2’-O-methyl modified IGF-IR specific siRNA are able to downregulate IGF-IR expression, block IGF-IR signaling, and suppress tumor growth in vivo by triggering antitumor immune responses [51]. siRNA-based therapies face two major barriers: the delivery of the large and highly charged molecules to the targets [52] and the transient effects of the downregulation of the target gene. In pre-clinical in vivo studies, the latter could be solved by developing in vivo stable and inducible long-term expression of target short hairpin RNA under the control of doxycycline, tetracycline, or other dimerizing drugs [53]. Specific microRNAs inhibited cancer cell proliferation, motility, invasion, xenograft tumor growth, and metastasis in different cancers by downregulation of IGF-IR expression [54, 55]. Typically these microRNAs have approximately 22 nucleotides and usually have more than one target; potential drug candidates need to be carefully examined to exclude off-target effects before evaluation in clinical trials. Introduction of kinase deficient mutation into IGF-IR as a gene transfer strategy could also be an alternative approach to suppress IGF-IR signaling pathway and result in tumor suppression [56].

Targeting IGF/insulin downstream signaling pathways

As noted, PI3K/AKT and Ras-MAPK axis are two well-established intracellular signal networks downstream of IGF/insulin signaling. Therefore, several key molecules in these pathways might be relevant targets for drug development including mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a serine/threonine protein kinase. Activation of mTOR upon growth factor stimulation subsequently induces the activation of ribosomal p70 S6 kinase (S6K1) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein-1 (4EBP1). Phosphorylated 4EBP1 releases eIF4E, the latter recruits elF4G to form eIF4F complex, which then binds to the 5’ mRNA cap and initiates cap-dependent mRNA-protein translation, thereby regulating cell growth and proliferation. Rapamycin and its analogs, everolimus (Novartis), temsirolimus (Pfizer) and ridaforolimus (Merck), have been developed to inhibit mTOR. Based on preclinical data using breast cancer cell lines [57–60] and mouse tumor models [61], both temsirolimus and everolimus have been approved for cancer treatment. Two recently published reports showed that everolimus combined with endocrine therapies were of benefit. In hormone refractory patients, tamoxifen plus everolimus resulted in increased clinical benefit compared to tamoxifen alone with improved time to progression and overall survival in hormone receptor (HR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) 2-negative metastatic breast cancer patients [62]. In a similar patient population, everolimus combined with the aromatase inhibitor exemestane showed improved progression-free survival in HR positive advanced breast cancer patients [63].

These promising clinical studies provide important evidence that anti-ER therapies can be combined with anti-signaling strategies. However, some caution is warranted in using mTOR inhibitors with the IGF system. Normally, IGF stimulation results in activation of S6K1, which negatively regulates adaptor protein insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS1) function by phosphorylation. IRS1 phosphorylation results in degradation of IRS1 protein and suppression of IRS1 gene expression [64]. mTOR inhibitors disrupt this negative feedback loop and enhance IGF/insulin signaling and subsequent PI3K/AKT activation [65].

Combination therapy with anti-IGF-IR agents might be needed to address this problem and will be discussed later. Beyond mTOR inhibitors, other small molecule inhibitors of the downstream pathways, such as PI3K inhibitor LY294002 [66], S6K1 inhibitor H89 [57], MAPK inhibitor U0126 [57, 67], and dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 [68] are currently in preclinical and clinical studies. The important translation initiation protein 4EBP1 could also be a potential drug target to terminate IGF/insulin signaling induced cap-dependent translation.

Crosstalk and combination therapies

IGF-IR monoclonal antibodies and mTOR inhibitors

As noted above, mTOR inhibitors affect the S6K1-IRS1 negative feedback loop and result in enhanced PI3K- AKT activation through IGF-IR signaling [69]. If this pathway represents a resistance mechanism for the mTOR inhibitors, then co-targeting IGF-IR and mTOR might result in enhanced clinical benefit over mTOR inhibitor monotherapy. Studies showed that dual inhibition of IGF-IR and mTOR improved antitumor activity in vitro and in breast cancer and other cancer patient tumor samples [69, 70]. Currently, Merck is determining the benefits of IGF-IR monoclonal antibody (dalotuzumab) and mTOR inhibitor (ridaforolimus) combination therapy in breast cancer patients with ER-positive tumors (NCT01220570, NCT01234857). Amgen is evaluating the clinical benefits of combining ganitumab with everolimus in patients having advanced cancers (NCT01061788, NCT01122199). The results of these clinical trials are expected to reveal the benefits of co-targeting IGF-IR and mTOR [71]. It is worth noting that drugs acting as dual inhibitors of PI3K and mTOR, such as NVP-BEZ235, also demonstrated improved antitumor efficacy compared to mTOR inhibitors alone [68, 72, 73].

Targeting IGF-IR/IR and estrogen receptor-α (ERα)

Cross talk between IGF/insulin system and estrogen receptor signaling pathway is well established [42, 57, 74]. IGF/insulin signaling activates ERα via PI3K/AKT and/or MAPK pathways respectively by phosphorylating ERα serine167 and/or ERαalanine118 [57, 75–77]. Estrogen increases expression of several key genes in the IGF signaling pathway including IGF-II [78], IGF-IR, and IRS1 [79], while decreasing expression of other genes, such as IGFBP-3 [80] and IGF-IIR [81]. Thus, the overall effect of estrogen on the IGF/insulin system is to positively regulate signaling.

Acquired resistance to anti-estrogen therapies is an important clinical problem. Since ERα may function together with IGF-IR signaling to enhance cell survival [82], targeting both pathways may have value. More recently, microarray data suggest that a gene signature co-regulated by IGF-I and estrogen correlated with poor prognosis in human breast cancer [67], which also implies dual inhibition of IGF-IR and ER pathway may be necessary in certain breast cancer subtypes.

However, the clinical trials using the combination therapy for patients with endocrine-resistant breast cancer have been disappointing [83]. In these trials, most women had already developed resistance to anti-ER therapies. In most of the reported trials, the anti-IGF-IR strategies were tested as the second or third line endocrine therapies.

We have recently shown that tamoxifen-resistant (TamR) cells and tumors lose expression of IGF-IR while maintaining IR expression. These findings suggest IGF-IR is a poor target in tamoxifen resistant tumors and IR might be an alternative option in treating TamR breast cancer [42]. Patients with tamoxifen resistant tumors also show loss of IGF-IR at the time of progression on tamoxifen [84]. Thus, endocrine resistant patients might not be the best candidates for anti-IGF-IR therapies. However, there are other ways to target IGF-IR and IR with small molecule TKIs, ligand neutralizing antibodies, or even growth hormone receptor antagonists, so the final word about the clinical relevance of these cross talk pathways is not yet settled.

Targeting IGF-IR and human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)

About 30% of the patients with invasive breast cancers have amplification or overexpression of EGFR2 (HER2), which is associated with poor prognosis breast cancer [85–87]. Trastuzumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the extracellular domain of RTK HER2 [88]. Trastuzumab initially showed outstanding anti-tumor efficacy in patients with HER2 positive breast cancer in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy. However, not all patients benefit from this regimen and in advanced breast cancer, resistance develops in about one year [89, 90]. IGF-IR and HER2 are reported to form heterodimers in trastuzumab-resistant breast cells [86]. Further, IGF-I was shown to activate HER2 signaling in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer cells but not parental cells. Inhibition of IGF signaling resulted in restoration of trastuzumab sensitivity to resistant cells [86, 91, 92]. These preclinical findings led to several clinical trials aimed at evaluating the benefits of co-targeting IGF-IR and HER2 in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer patients (NCT01479179, NCT00788333, NCT00684983, and NCT01111825).

Other combination therapy strategies

IGF/insulin signaling and chemotherapy

Combining either IGF-IR monoclonal antibodies or IGF-IR TKI could enhance doxorubicin drug efficacy [39, 93]. We demonstrated that giving cytotoxic chemotherapy first or concurrently with IGF-IR inhibitors resulted in a better tumor response. In contrast, IGF-IR prior to cytotoxic chemotherapy did not improve the benefits of doxorubicin and may represent an interference pathway between cytotoxic chemotherapy and IGF-IR inhibitors. These results suggest a combination of IGF-IR blockade and chemotherapy works in a sequencing-dependent fashion [39].

IGF/insulin system therapy and metformin

As noted above, IGF-IR blockade is predicted and proven to result in compensational upregulation of circulating IGFs and insulin. These effects may cause hyperinsulinemia and be clinically manifested as metabolic syndrome or frank type-2 diabetes [6, 43, 59, 94–96]. Therefore, combining insulin sensitizing drugs to decrease serum levels of insulin with metformin might be necessary to attenuate the metabolic effects of the anti-IGF-IR/IR drugs. The I-SPY2 trial of neoadjuvant breast cancer therapy will test the therapeutic value of combining ganitumab, metformin and paclitaxel. The metformin will help to manage any acquired insulin resistance induced by ganitumab [97]. Metformin also reduces reactive oxygen species in mitochondria, which potentially would be important to inhibit tumorigenesis independent of the effects on glucose metabolism [43, 98]. Thus metformin combined with IGF-IR blockades may not only attenuate the drug-induced hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, but may also exhibit antitumor efficacy.

Future Directions

In order to maximize patient response to the emerging anti-IGF/insulin signaling therapies and accelerate developments of these antitumor drugs, the identification of therapeutic predictive biomarkers will need great attention.

The ‘figitumumab downfall’ raises an important question: what molecular attributes will likely be predictive of tumor dependence on IGF-IR? In these figitumumab clinical trials patients were not selected based upon any molecular markers. Microarray analysis has been used to determine sarcoma and neuroblastoma cell lines either sensitive or resistant to a TKI of IGF1R/IR, (BMS-536924). These data show that the mRNA levels of IGF-I and IGF-II highly correlated with cell response to BMS-536924 [99, 100]. Interestingly, the mRNA level of IGF1R did not meet the stringent statistical significance threshold to serve as an independent predictive biomarker, suggesting hybrid receptor mediated some of the IGF-I/IGF-II effects in these cells. Similarly, in a report addressing the sensitivity profile of another anti-IGF1R TKI, OSI-906 in colorectal cancer, the level of the phosphorylation status of IGF1R alone did not have positive correlation with cell sensitivity to OSI-906 [101]. These findings suggest a more complete definition of the IGF system signaling components is likely to assist in the clinical evaluation of anti-IGF1R therapies. Distinct receptor composition on the cell surface may influence cancer cell biology and predict sensitivity to anti-IGF1R therapy. Many studies have supported the important role of holo-IGF1R in cancer [9, 10, 102], yet the function of the IGF1R/IR hybrid receptor has not been well studied. The function of hybrid receptor signaling [18, 35]compared to holo-IGF1R and holo-IR receptors needs further characterization in order to serve as predictive biomarkers in breast cancer patients.

In addition, the IGF/insulin downstream signaling molecules may be important to predict a patient’s response to the anti-IGF1R therapy. As adaptor molecules are important components to transduce IGF1R signaling, the preferential expression of specific IRS isoforms in breast cancer cells has been linked to distinct signal transduction pathways and shown to mediate distinct biological behavior [103–106]. Our laboratory studied the gene expression profiles of a series of T47D variant cell lines with differential IRS adaptor protein expression to develop predictive IGF-I pathway biomarkers in breast cancer cells (submitted, Becker et al.). The results have suggested IGF-induced gene expression is IRS-dependent and highly conserved. In addition, this previous study has revealed several genes regulated specifically by either IRS-1 or IRS-2.

Besides cell surface composition of the receptors and preferential expressions of IRS adaptor proteins, other components of the IGF/insulin system may serve as predictive biomarkers for therapeutic outcomes and disease prognosis. Pre-treatment level of free IGF-I has been shown to predict NSCLC patients’ benefit from IGF-IR monoclonal antibody [107]. IGF-IR nuclear staining has been reported to associate with a better progression-free survival and overall survival in a small group of soft tissue sarcoma patients treated with IGF-IR antibody [108]. A recent report suggested IGFBP5 expression was associated with resistance to IGF-IR/IR targeted therapy. Furthermore, increased IGFBP5/IGFBP4 ratio is associated with decreased sensitivity to IGF-IR/IR inhibition and worse prognosis in breast cancer patients [109].

In sum, the IGF/insulin system is complex. Simply targeting one receptor may not be sufficient enough to completely inhibit tumor behavior. Additional preclinical data are needed to unravel the true clinical benefit of the anti-IGF/insulin targeted agents in breast cancer patients.

Conclusion

Although preclinical evidence provides strong rationale for clinically targeting IGF/insulin signaling, the withdrawal of figitumumab from phase III clinical trials raised significant concerns about the clinical utility of targeting IGF-IR with a monoclonal antibody. However, we still believe that IGF-IR antibodies can be clinically beneficial in a subset of breast cancer patients through the use of appropriate predictive biomarkers coupled with cautious monitoring of insulin levels during the therapy. Other drugs affecting IGF/insulin signaling such as TKIs, ligand neutralizers, and mTOR inhibitors show promise, most likely in combination with conventional and novel agents. A more insightful understanding of IGF/insulin system and its crosstalk with other critical signaling pathways in breast cancer cells is needed to optimize the targeting of the IGF/insulin system in breast cancer.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grants R01CA74285, P30 CA 077598, P50CA116201, and Komen for the Cure KG101465.

References

- 1.Osborne CK. Tamoxifen in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(22):1609–1618. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811263392207. doi:10.1056/NEJM199811263392207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gianni L, Dafni U, Gelber RD, Azambuja E, Muehlbauer S, Goldhirsch A, et al. Treatment with trastuzumab for 1 year after adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer: a 4-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(3):236–244. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70033-X. doi:S1470-2045(11)70033-X [pii]10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70033-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, Goldhirsch A, Untch M, Smith I, et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1659–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052306. doi:353/16/1659[pii]10.1056/NEJMoa052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Closas M, Hall P, Nevanlinna H, Pooley K, Morrison J, Richesson DA, et al. Heterogeneity of breast cancer associations with five susceptibility loci by clinical and pathological characteristics. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(4):e1000054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000054. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sachdev D. Regulation of breast cancer metastasis by IGF signaling. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2008;13(4):431–441. doi: 10.1007/s10911-008-9105-5. doi:10.1007/s10911-008-9105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollak M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(12):915–928. doi: 10.1038/nrc2536. doi:nrc2536 [pii]10.1038/nrc2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Favoni RE, de Cupis A, Ravera F, Cantoni C, Pirani P, Ardizzoni A, et al. Expression and function of the insulin-like growth factor I system in human non-small-cell lung cancer and normal lung cell lines. Int J Cancer. 1994;56(6):858–866. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910560618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arteaga CL, Kitten LJ, Coronado EB, Jacobs S, Kull FC, Jr, Allred DC, et al. Blockade of the type I somatomedin receptor inhibits growth of human breast cancer cells in athymic mice. J Clin Invest. 1989;84(5):1418–1423. doi: 10.1172/JCI114315. doi:10.1172/JCI114315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaleko M, Rutter WJ, Miller AD. Overexpression of the human insulinlike growth factor I receptor promotes ligand-dependent neoplastic transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10(2):464–473. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HJ, Litzenburger BC, Cui X, Delgado DA, Grabiner BC, Lin X, et al. Constitutively active type I insulin-like growth factor receptor causes transformation and xenograft growth of immortalized mammary epithelial cells and is accompanied by an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition mediated by NF-kappaB and snail. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(8):3165–3175. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01315-06. doi:MCB.01315-06 [pii]10.1128/MCB.01315-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachdev D, Hartell JS, Lee AV, Zhang X, Yee D. A dominant negative type I insulin-like growth factor receptor inhibits metastasis of human cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(6):5017–5024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305403200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M305403200 M305403200 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachdev D, Li SL, Hartell JS, Fujita-Yamaguchi Y, Miller JS, Yee D. A chimeric humanized single-chain antibody against the type I insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor renders breast cancer cells refractory to the mitogenic effects of IGF-I. Cancer Res. 2003;63(3):627–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burtrum D, Zhu Z, Lu D, Anderson DM, Prewett M, Pereira DS, et al. A fully human monoclonal antibody to the insulin-like growth factor I receptor blocks ligand-dependent signaling and inhibits human tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 2003;63(24):8912–8921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arteaga CL, Osborne CK. Growth inhibition of human breast cancer cells in vitro with an antibody against the type I somatomedin receptor. Cancer Res. 1989;49(22):6237–6241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanno S, Mitsuuchi Y, Altomare DA, Xiao GH, Testa JR. AKT activation up-regulates insulin-like growth factor I receptor expression and promotes invasiveness of human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(2):589–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciampolillo A, De Tullio C, Giorgino F. The IGF-I/IGF-I receptor pathway: Implications in the Pathophysiology of Thyroid Cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12(24):2881–2891. doi: 10.2174/092986705774454715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frasca F, Pandini G, Scalia P, Sciacca L, Mineo R, Costantino A, et al. Insulin receptor isoform A, a newly recognized, high-affinity insulin-like growth factor II receptor in fetal and cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(5):3278–3288. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belfiore A, Frasca F, Pandini G, Sciacca L, Vigneri R. Insulin receptor isoforms and insulin receptor/insulin-like growth factor receptor hybrids in physiology and disease. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(6):586–623. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weichhaus M, Broom J, Wahle K, Bermano G. A novel role for insulin resistance in the connection between obesity and postmenopausal breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(2):745–752. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1480. doi:10.3892/ijo.2012.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Algire C, Amrein L, Zakikhani M, Panasci L, Pollak M. Metformin blocks the stimulative effect of a high-energy diet on colon carcinoma growth in vivo and is associated with reduced expression of fatty acid synthase. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(2):351–360. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0252. doi:10.1677/ERC-09-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunter MJ, Hoover DR, Yu H, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Rohan TE, Manson JE, et al. Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(1):48–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn415. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferguson RD, Novosyadlyy R, Fierz Y, Alikhani N, Sun H, Yakar S, et al. Hyperinsulinemia enhances c-Myc-mediated mammary tumor development and advances metastatic progression to the lung in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2012;14(1):R8. doi: 10.1186/bcr3089. doi:10.1186/bcr3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guevara-Aguirre J, Balasubramanian P, Guevara-Aguirre M, Wei M, Madia F, Cheng CW, et al. Growth hormone receptor deficiency is associated with a major reduction in pro-aging signaling, cancer, and diabetes in humans. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(70) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001845. 70ra13. doi:3/70/70ra13 [pii] 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szereday Z, Schally AV, Varga JL, Kanashiro CA, Hebert F, Armatis P, et al. Antagonists of growth hormone-releasing hormone inhibit the proliferation of experimental non-small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63(22):7913–7919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin D, Vreeland F, Schaaf LJ, Millham R, Duncan BA, Sharma A. Clinical pharmacodynamic effects of the growth hormone receptor antagonist pegvisomant: implications for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(3):1000–1009. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1910. doi:13/3/1000 [pii] 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao J, Chesebrough JW, Cartlidge SA, Ricketts SA, Incognito L, Veldman-Jones M, et al. Dual IGF-I/II-neutralizing antibody MEDI-573 potently inhibits IGF signaling and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2011;71(3):1029–1040. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2274. doi:0008-5472.CAN-10-2274 [pii] 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adam PJ, Friedbichler K, Hofmann MH, Bogenrieder T, Borges E, Adolf GR. BI 836845, a fully human IGF ligand neutralizing antibody, to improve the efficacy of rapamycin by blocking rapamacyin-induced AKT activation. ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago: J Clin Oncol. 2012 p. suppl; abstr 3092. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jogie-Brahim S, Feldman D, Oh Y. Unraveling insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 actions in human disease. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(5):417–437. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0028. doi:er.2008-0028 [pii] 10.1210/er.2008-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alami N, Page V, Yu Q, Jerome L, Paterson J, Shiry L, et al. Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 inhibits tumor growth and targets the Akt pathway in lung and colon cancer models. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2008;18(6):487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2008.04.002. doi:S1096-6374(08)00061-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.ghir.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerome L, Alami N, Belanger S, Page V, Yu Q, Paterson J, et al. Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 inhibits growth of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-overexpressing breast tumors and potentiates herceptin activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66(14):7245–7252. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papa V, Pezzino V, Costantino A, Belfiore A, Giuffrida D, Frittitta L, et al. Elevated insulin receptor content in human breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 1990;86(5):1503–1510. doi: 10.1172/JCI114868. doi:10.1172/JCI114868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathieu MC, Clark GM, Allred DC, Goldfine ID, Vigneri R. Insulin receptor expression and clinical outcome in node-negative breast cancer. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1997;109(6):565–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haluska P, Shaw HM, Batzel GN, Yin D, Molina JR, Molife LR, et al. Phase I dose escalation study of the anti insulin-like growth factor-I receptor monoclonal antibody CP-751,871 in patients with refractory solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(19):5834–5840. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1118. doi:13/19/5834 [pii] 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avnet S, Sciacca L, Salerno M, Gancitano G, Cassarino MF, Longhi A, et al. Insulin receptor isoform A and insulin-like growth factor II as additional treatment targets in human osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69(6):2443–2452. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandini G, Wurch T, Akla B, Corvaia N, Belfiore A, Goetsch L. Functional responses and in vivo anti-tumour activity of h7C10: a humanised monoclonal antibody with neutralising activity against the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor and insulin/IGF-1 hybrid receptors. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(8):1318–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.03.009. doi:S0959-8049(07)00202-X [pii] 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sachdev D, Yee D. Disrupting insulin-like growth factor signaling as a potential cancer therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(1):1–12. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0080. doi:6/1/1 [pii] 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan PD, Neven P, Blackwell KL, Dirix LY, Barrios CH, Miller JWH, et al. Figitumumab plus exemestane versus exemestane as first-line treatment of postmenopausal hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer: a randomized, open-label phase II trial. Cancer Res. 2011;71(24 Suppl.) 239s, Abs nr P1-17-01. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng X, Sachdev D, Zhang H, Gaillard-Kelly M, Yee D. Sequencing of type I insulin-like growth factor receptor inhibition affects chemotherapy response in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(8):2840–2849. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1401. doi:1078-0432.CCR-08-1401 [pii] 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sachdev D, Zhang X, Matise I, Gaillard-Kelly M, Yee D. The type I insulin-like growth factor receptor regulates cancer metastasis independently of primary tumor growth by promoting invasion and survival. Oncogene. 2010;29(2):251–262. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.316. doi:onc2009316 [pii] 10.1038/onc.2009.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atzori F, Tabernero J, Cervantes A, Prudkin L, Andreu J, Rodriguez-Braun E, et al. A phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of dalotuzumab (MK-0646), an anti-insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(19):6304–6312. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3336. doi:1078-0432.CCR-10-3336 [pii] 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fagan DH, Uselman RR, Sachdev D, Yee D. Acquired resistance to tamoxifen is associated with loss of the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF1R): implications for breast cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2012 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0684. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pollak M. The insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptor family in neoplasia: an update. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(3):159–169. doi: 10.1038/nrc3215. doi:nrc3215 [pii] 10.1038/nrc3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belfiore A, Malaguarnera R. Insulin receptor and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18(4):R125–R147. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0074. doi:ERC-11-0074 [pii] 10.1530/ERC-11-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qiu J, Yang R, Rao Y, Du Y, Kalembo FW. Risk Factors for Breast Cancer and Expression of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-2 (IGF-2) in Women with Breast Cancer in Wuhan City, China. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036497. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036497 PONE-D-12-08122 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward A, Bates P, Fisher R, Richardson L, Graham CF. Disproportionate growth in mice with Igf-2 transgenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(22):10365–10369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades NS, McMullan CJ, Poulaki V, Shringarpure R, Akiyama M, et al. Inhibition of the insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 tyrosine kinase activity as a therapeutic strategy for multiple myeloma, other hematologic malignancies, and solid tumors. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(3):221–230. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia-Echeverria C, Pearson MA, Marti A, Meyer T, Mestan J, Zimmermann J, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of NVP-AEW541-A novel, potent, and selective inhibitor of the IGF-IR kinase. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(3):231–239. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carboni JM, Wittman M, Yang Z, Lee F, Greer A, Hurlburt W, et al. BMS-754807, a small molecule inhibitor of insulin-like growth factor-1R/IR. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(12):3341–3349. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0499. doi:1535-7163.MCT-09-0499 [pii] 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hou X, Huang F, Macedo LF, Harrington SC, Reeves KA, Greer A, et al. Dual IGF-1R/InsR inhibitor BMS-754807 synergizes with hormonal agents in treatment of estrogen-dependent breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(24):7597–7607. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1080. doi:0008-5472.CAN-11-1080 [pii] 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Durfort T, Tkach M, Meschaninova MI, Rivas MA, Elizalde PV, Venyaminova AG, et al. Small interfering RNA targeted to IGF-IR delays tumor growth and induces proinflammatory cytokines in a mouse breast cancer model. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029213. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029213 PONE-D-11-12038 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG. Knocking down barriers: advances in siRNA delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(2):129–138. doi: 10.1038/nrd2742. doi:nrd2742 [pii] 10.1038/nrd2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones RA, Campbell CI, Wood GA, Petrik JJ, Moorehead RA. Reversibility and recurrence of IGF-IR-induced mammary tumors. Oncogene. 2009;28(21):2152–2162. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.79. doi:onc200979 [pii] 10.1038/onc.2009.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen K, Liang Q, Xu K, Cui D, Jiang L, Yin P, et al. MiR-139 inhibits invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer by targeting the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84(3):320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.04.017. doi:S0006-2952(12)00321-8 [pii] 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kong KL, Kwong DL, Chan TH, Law SY, Chen L, Li Y, et al. MicroRNA-375 inhibits tumour growth and metastasis in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma through repressing insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Gut. 2012;61(1):33–42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300178. doi:gutjnl-2011-300178 [pii] 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalebic T, Blakesley V, Slade C, Plasschaert S, Leroith D, Helman LJ. Expression of a kinase-deficient IGF-I-R suppresses tumorigenicity of rhabdomyosarcoma cells constitutively expressing a wild type IGF-I-R. Int J Cancer. 1998;76(2):223–227. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980413)76:2<223::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-z. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980413)76:2<223::AIDIJC9> 3.0.CO;2-Z [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Becker MA, Ibrahim YH, Cui X, Lee AV, Yee D. The IGF pathway regulates ERalpha through a S6K1-dependent mechanism in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25(3):516–528. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0373. doi:me.2010-0373 [pii] 10.1210/me.2010-0373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu H, Scholz C, Zang C, Schefe JH, Habbel P, Regierer AC, et al. Metformin and the mTOR Inhibitor Everolimus (RAD001) Sensitize Breast Cancer Cells to the Cytotoxic Effect of Chemotherapeutic Drugs In Vitro. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(5):1627–1637. doi:32/5/1627 [pii]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Noh WC, Mondesire WH, Peng J, Jian W, Zhang H, Dong J, et al. Determinants of rapamycin sensitivity in breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(3):1013–1023. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rivera VM, Squillace RM, Miller D, Berk L, Wardwell SD, Ning Y, et al. Ridaforolimus (AP23573; MK-8669), a potent mTOR inhibitor, has broad antitumor activity and can be optimally administered using intermittent dosing regimens. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(6):1059–1071. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0792. doi:1535-7163.MCT-10-0792 [pii] 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu K, Toral-Barza L, Discafani C, Zhang WG, Skotnicki J, Frost P, et al. mTOR, a novel target in breast cancer: the effect of CCI-779, an mTOR inhibitor, in preclinical models of breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8(3):249–258. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bachelot T, Bourgier C, Cropet C, Ray-Coquard I, Ferrero JM, Freyer G, et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Everolimus in Combination With Tamoxifen in Patients With Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer With Prior Exposure to Aromatase Inhibitors: A GINECO Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.0708. doi:JCO.2011.39.0708 [pii] 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, Burris HA, 3rd, Rugo HS, Sahmoud T, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):520–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harrington LS, Findlay GM, Gray A, Tolkacheva T, Wigfield S, Rebholz H, et al. The TSC1-2 tumor suppressor controls insulin-PI3K signaling via regulation of IRS proteins. J Cell Biol. 2004;166(2):213–223. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403069. doi:10.1083/jcb.200403069 jcb.200403069 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shi Y, Yan H, Frost P, Gera J, Lichtenstein A. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors activate the AKT kinase in multiple myeloma cells by up-regulating the insulin-like growth factor receptor/insulin receptor substrate-1/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase cascade. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4(10):1533–1540. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0068. doi:4/10/1533 [pii] 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clark AS, West K, Streicher S, Dennis PA. Constitutive and inducible Akt activity promotes resistance to chemotherapy, trastuzumab, or tamoxifen in breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1(9):707–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Casa AJ, Potter AS, Malik S, Lazard Z, Kuiatse I, Kim HT, et al. Estrogen and insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) independently down-regulate critical repressors of breast cancer growth. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(1):61–73. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1540-0. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1540-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brachmann SM, Hofmann I, Schnell C, Fritsch C, Wee S, Lane H, et al. Specific apoptosis induction by the dual PI3K/mTor inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 in HER2 amplified and PIK3CA mutant breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(52):22299–22304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905152106. doi:0905152106 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0905152106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O'Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. doi:66/3/1500 [pii] 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wan X, Harkavy B, Shen N, Grohar P, Helman LJ. Rapamycin induces feedback activation of Akt signaling through an IGF-1R-dependent mechanism. Oncogene. 2007;26(13):1932–1940. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209990. doi:1209990 [pii] 10.1038/sj.onc.1209990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Di Cosimo S, Bendell JC, Cervantes-Ruiperez A, Roda D, Prudkin L, Stein MN, et al. A phase I study of the oral mTOR inhibitor ridaforolimus (RIDA) in combination with the IGF-1R antibody dalotozumab (DALO) in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15) abstr 3008. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leung E, Kim JE, Rewcastle GW, Finlay GJ, Baguley BC. Comparison of the effects of the PI3K/mTOR inhibitors NVP-BEZ235 and GSK2126458 on tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11(11):938–946. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.11.15527. doi:15527 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cho DC, Cohen MB, Panka DJ, Collins M, Ghebremichael M, Atkins MB, et al. The efficacy of the novel dual PI3-kinase/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 compared with rapamycin in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(14):3628–3638. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3022. doi:1078-0432.CCR-09-3022 [pii] 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hamelers IH, Steenbergh PH. Interactions between estrogen and insulin-like growth factor signaling pathways in human breast tumor cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10(2):331–345. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tremblay GB, Tremblay A, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Labrie F, et al. Cloning, chromosomal localization, and functional analysis of the murine estrogen receptor beta. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11(3):353–365. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.3.9902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Campbell RA, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Patel NM, Constantinidou D, Ali S, Nakshatri H. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT-mediated activation of estrogen receptor alpha: a new model for anti-estrogen resistance. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(13):9817–9824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010840200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M010840200 M010840200 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martin MB, Franke TF, Stoica GE, Chambon P, Katzenellenbogen BS, Stoica BA, et al. A role for Akt in mediating the estrogenic functions of epidermal growth factor and insulin-like growth factor I. Endocrinology. 2000;141(12):4503–4511. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee AV, Darbre P, King RJ. Processing of insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF-II) by human breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1994;99(2):211–220. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90010-8. doi:0303-7207(94)90010-8 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee AV, Jackson JG, Gooch JL, Hilsenbeck SG, Coronado-Heinsohn E, Osborne CK, et al. Enhancement of insulin-like growth factor signaling in human breast cancer: estrogen regulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 expression in vitro and in vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13(5):787–796. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.5.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huynh H, Yang X, Pollak M. Estradiol and antiestrogens regulate a growth inhibitory insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 autocrine loop in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(2):1016–1021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mathieu M, Vignon F, Capony F, Rochefort H. Estradiol down-regulates the mannose-6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor-II receptor gene and induces cathepsin-D in breast cancer cells: a receptor saturation mechanism to increase the secretion of lysosomal proenzymes. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5(6):815–822. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-6-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Song RX, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Bao Y, Yue W, Wang JP, et al. Estrogen utilization of IGF-1-R and EGF-R to signal in breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;118(4–5):219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.09.018. doi:S0960-0760(09)00246-5 [pii] 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kaufman PA, Ferrero JM, Bourgeois H, Kennecke H, De Boer R, Jacot W, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Study of AMG 479 With Exemestane (E) or Fulvestrant (F) in Postmenopausal Women With Hormone-Receptor Positive (HR+) Metastatic (M) or Locally Advanced (LA) Breast Cancer (BC) Cancer Res. 2010;70(76s) [Google Scholar]

- 84.Drury SC, Detre S, Leary A, Salter J, Reis-Filho J, Barbashina V, et al. Changes in breast cancer biomarkers in the IGF1R/PI3K pathway in recurrent breast cancer after tamoxifen treatment. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18(5):565–577. doi: 10.1530/ERC-10-0046. doi:ERC-10-0046 [pii] 10.1530/ERC-10-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tan M, Yu D. Molecular mechanisms of erbB2-mediated breast cancer chemoresistance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;608:119–129. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-74039-3_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nahta R, Yuan LX, Zhang B, Kobayashi R, Esteva FJ. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterodimerization contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(23):11118–11128. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3841. doi:65/23/11118 [pii] 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER- 2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235(4785):177–182. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carter P, Presta L, Gorman CM, Ridgway JB, Henner D, Wong WL, et al. Humanization of an anti-p185HER2 antibody for human cancer therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(10):4285–4289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Esteva FJ, Valero V, Booser D, Guerra LT, Murray JL, Pusztai L, et al. Phase II study of weekly docetaxel and trastuzumab for patients with HER-2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(7):1800–1808. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Albanell J, Baselga J. Unraveling resistance to trastuzumab (Herceptin): insulin-like growth factor-I receptor, a new suspect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(24):1830–1832. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.24.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Browne BC, Crown J, Venkatesan N, Duffy MJ, Clynes M, Slamon D, et al. Inhibition of IGF1R activity enhances response to trastuzumab in HER-2-positive breast cancer cells. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(1):68–73. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq349. doi:mdq349 [pii] 10.1093/annonc/mdq349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rowe DL, Ozbay T, Bender LM, Nahta R. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid, a cytotoxic insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/HER2 inhibitor in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(7):1900–1908. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0012. doi:7/7/1900 [pii] 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zeng X, Zhang H, Oh A, Zhang Y, Yee D. Enhancement of doxorubicin cytotoxicity of human cancer cells by tyrosine kinase inhibition of insulin receptor and type I IGF receptor. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(1):117–126. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1713-x. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1713-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ma J, Giovannucci E, Pollak M, Leavitt A, Tao Y, Gaziano JM, et al. A prospective study of plasma C-peptide and colorectal cancer risk in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(7):546–553. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yee D. Targeting insulin-like growth factor pathways. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(4):465–468. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602963. doi:6602963 [pii] 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee AV, Yee D. Targeting IGF-1R: at a crossroad. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25(6):535–536. discussion 51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barker AD, Sigman CC, Kelloff GJ, Hylton NM, Berry DA, Esserman LJ. I-SPY 2: an adaptive breast cancer trial design in the setting of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86(1):97–100. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.68. doi:clpt200968 [pii] 10.1038/clpt.2009.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Algire C, Moiseeva O, Deschenes-Simard X, Amrein L, Petruccelli L, Birman E, et al. Metformin reduces endogenous reactive oxygen species and associated DNA damage. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5(4):536–543. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0536. doi:1940-6207.CAPR-11-0536 [pii] 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Litzenburger BC, Creighton CJ, Tsimelzon A, Chan BT, Hilsenbeck SG, Wang T, et al. High IGF-IR activity in triple-negative breast cancer cell lines and tumorgrafts correlates with sensitivity to anti-IGF-IR therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(8):2314–2327. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1903. doi:1078-0432.CCR-10-1903 [pii] 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Huang F, Greer A, Hurlburt W, Han X, Hafezi R, Wittenberg GM, et al. The mechanisms of differential sensitivity to an insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor inhibitor (BMS-536924) and rationale for combining with EGFR/HER2 inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2009;69(1):161–170. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0835. doi:69/1/161 [pii] 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pitts TM, Tan AC, Kulikowski GN, Tentler JJ, Brown AM, Flanigan SA, et al. Development of an integrated genomic classifier for a novel agent in colorectal cancer: approach to individualized therapy in early development. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(12):3193–3204. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3191. doi:1078-0432.CCR-09-3191 [pii] 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Carboni JM, Lee AV, Hadsell DL, Rowley BR, Lee FY, Bol DK, et al. Tumor development by transgenic expression of a constitutively active insulin-like growth factor I receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65(9):3781–3787. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shaw LM. Identification of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and IRS-2 as signaling intermediates in the alpha6beta4 integrin-dependent activation of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and promotion of invasion. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(15):5082–5093. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5082-5093.2001. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.15.5082-5093.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jackson JG, Zhang X, Yoneda T, Yee D. Regulation of breast cancer cell motility by insulin receptor substrate-2 (IRS-2) in metastatic variants of human breast cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2001;20(50):7318–7325. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204920. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jackson JG, White MF, Yee D. Insulin receptor substrate-1 is the predominant signaling molecule activated by insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin, and interleukin-4 in estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(16):9994–10003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Byron SA, Horwitz KB, Richer JK, Lange CA, Zhang X, Yee D. Insulin receptor substrates mediate distinct biological responses to insulin-like growth factor receptor activation in breast cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(9):1220–1228. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603354. doi:6603354 [pii] 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gualberto A, Hixon ML, Karp DD, Li D, Green S, Dolled-Filhart M, et al. Pre-treatment levels of circulating free IGF-1 identify NSCLC patients who derive clinical benefit from figitumumab. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(1):68–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605972. doi:6605972 [pii] 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 108.Asmane I, Watkin E, Alberti L, Duc A, Marec-Berard P, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor (IGF-1R) exclusive nuclear staining: A predictive biomarker for IGF-1R monoclonal antibody (Ab) therapy in sarcomas. Eur J Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.009. doi:S0959-8049(12)00409-1 [pii] 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Becker MA, Hou X, Harrington SC, Weroha SJ, Gonzalez SE, Jacob KA, et al. IGFBP ratio confers resistance to IGF targeting and correlates with increased invasion and poor outcome in breast tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(6):1808–1817. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1806. doi:1078-0432.CCR-11-1806 [pii] 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]