Abstract

Purpose

There is a strong consensus for surgical treatment of reruptures and neglected ruptures of the Achilles tendon. A number of different surgical techniques have been described and several of these methods include extensive surgical exposure to the calf and technically demanding tendon transfers. The overall risk of complications is high and in particular the risk for wound healing problems, which are triggered by an increased tension in the skin when inserting a bulky graft to cover the rupture. In order to reduce the risk for wound healing problems a new, less complicated surgical technique was developed, as described in this study.

Methods

Nine consecutive patients (including six chronic ruptures and three reruptures) with complicating co-morbidities and with a tendon defect between three and eight centimetres were operated upon using the described novel technique. Patient-reported functional outcome was reported after two to eight years.

Results

All tendon defects were successfully repaired. Neither early nor late surgical complications occurred. High patient satisfaction was reported for all patients.

Conclusions

The new surgical technique with a medial Achilles tendon island flap seems to be safe and results in a good patient reported outcome.

Introduction

The treatment of reruptures and neglected ruptures of the Achilles tendon presents a challenge for every orthopaedic surgeon. Compared to acute ruptures [1], there is a strong consensus for surgical treatment of reruptures and neglected Achilles tendon ruptures. A number of different surgical techniques have been described including local tissue augmentation [2], free flaps [3] or turn-down flaps [4–6], tendon transfers [7], free tissue transfers or V-Y tendon alignment [8]. Since these late ruptures are fairly uncommon, only a small case series with limited follow-up of the results has been presented. Variations in study design and postoperative regimes makes comparison between different surgical techniques difficult and therefore no method has been shown to be superior or inferior to another. Primary repair with end-to-end suture, which in acute ruptures provide a good biomechanical strength to the rupture site [9], has however not been considered to be appropriate for neglected ruptures [10] due to fibrotic contraction and atrophy of the proximal tendinous complex, often resulting in a large gap in the tendon. Skin retraction over the rupture site and extensive surgical exposure to the calf increases the risk for complications, especially major wound healing problems [11]. In this study we present a novel technique to bridge the rupture gap with a medial Achilles tendon island flap. The major benefits of this method include the simplicity, preserved vascularity to the graft via a retrograde vascular pedicle and minimal amount of bulky tissue over the rupture site tension to the skin. Nine patients were operated upon using the described method. The purpose of this study was to describe the surgical method and report patient reported outcome after one to eight years.

Patients and methods

The case series include nine consecutive patients, six male and three female, operated upon by PH or LJL with assistance of a consultant plastic surgeon (BAR) between the years 2001 and 2009. The median age was 59 years (24–68 years). Three patients presented with neglected ruptures, three patients presented with delayed diagnosis (patients delay) and three patients presented with reruptures; one rerupture occurred after conservative treatment of a primary rupture, one rerupture occurred after a primary suture and one rerupture occurred after repair of a neglected rupture using a turn down flap [5]. Table 1 presents demographic and clinical data for each patient. One patient had non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) and one patient had a healed superficial wound infection before the final operation. The defect in the Achilles tendon (with the foot in neutral position) measured between three and eight centimetres in all cases (median five cm, preoperative data). The time from rupture/rerupture to the final procedure was one to 15 months in all cases (median three months).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Case | Gender | Age (years) | Indication for surgery | Tendon defect (cm) | Duration to surgery (months) | Follow-up (years) | Co-morbidity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Male | 34 | Rerupturea | 5 | 3 | 8.5 | |

| Case 2 | Male | 57 | Neglected | 8 | 5 | 5.1 | |

| Case 3 | Female | 59 | Reruptureb | 3 | 2 | 4.6 | NIDDM |

| Case 4 | Male | 62 | Neglected | 3 | 4 | 4.2 | |

| Case 5 | Male | 62 | Rerupturec | 7 | 8 | 3.1 | Previous wound infection |

| Case 6 | Male | 68 | Neglected | 7 | 15 | 1.9 | |

| Case 7 | Male | 66 | Delayed | 5 | 3 | 1.4 | |

| Case 8 | Female | 24 | Delayed | 3 | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Case 9 | Female | 58 | Delayed | 3 | 1 | 1.4 |

NIDDM non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus

a Rerupture of primary suture

b Rerupture after primary conservative treatment

c Rerupture after previous turn down flap

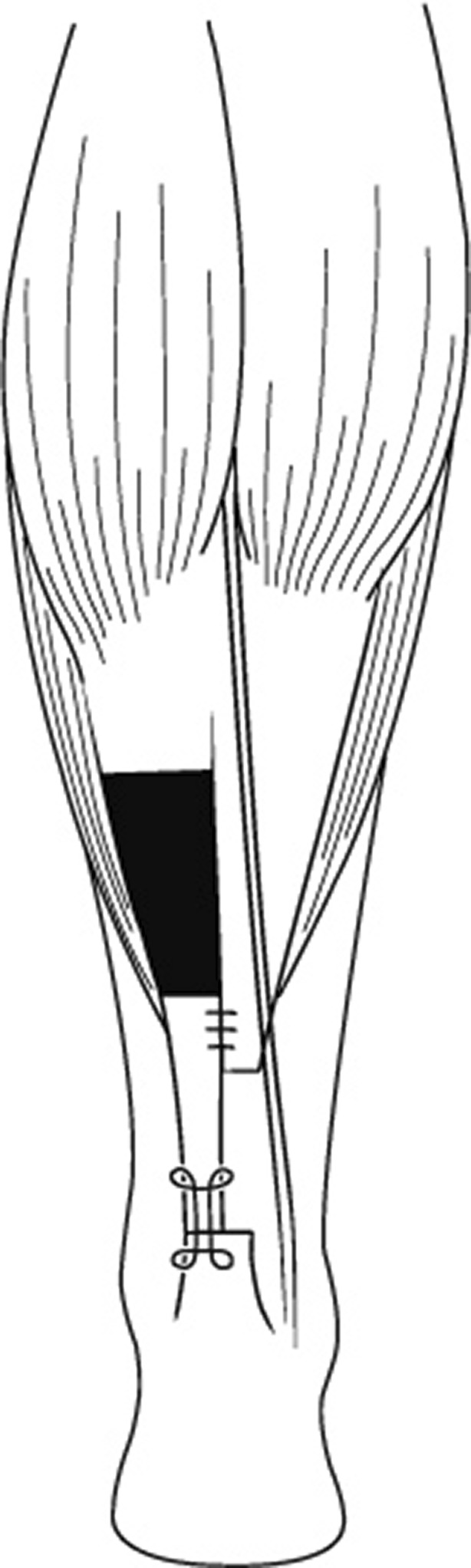

After a clinical diagnosis of a rerupture or a previously neglected Achilles tendon rupture the patients were operated upon in prone position under spinal anaesthesia using a method developed by the senior surgeon (PH) (Fig. 1). A posteromedial incision down to the tendon was made through skin, subcutaneous tissues and fascia keeping well on the medial side of the tendon. The scar tissue between the ruptured proximal and distal end was removed and the frayed ends trimmed down to fresh tissue. With the muscle under tension a flap was marked out from the midline of the proximal tendon end, going proximally in the midline and turning perpendicular over to the medial side on the gastrocnemius tendon aponeurosis. The length should add about 2 cm to the distance to bridge. The island flap was divided sharply taking care not to go deeper than through proper tendon tissue (respecting the posterior muscle belly and the blood supply on the anterior side of the tendon). The proximal Achilles tendon island flap was then advanced in the distal direction with a gentle but consistent traction until it bridged the gap and reached the distal tendon were it was sutured end to end with a modified Kessler suture to the middle of the distal tendon end using number 0 PDS suture. The tension was approximated so the foot reached a normal gravity equinus position if possible. The proximal tendon was then tacked over the midline to its lateral counterpart with single 2.0 PDS sutures with buried knots. The surgical procedure was finished by applying a below-knee plaster cast with the ankle in the equinus position. After three weeks the plaster was replaced and the ankle placed in a neutral position allowing full weight bearing. All patients were immobilised in plaster for eight to nine weeks, followed by physiotherapy for approximately six months. Within a prospective clinical audit, all complications to surgery were registered during six postoperative weeks. Finally, all patients were interviewed 1.1 to 8.5 years (median 3.1 years) after surgery using a predefined questionnaire to evaluate calf muscle function and residual symptoms affecting activities of daily life (ADL). Patient’s over-all satisfactory was measured with a four-grade scale with poor, fair, good and excellent over-all satisfaction after the surgical procedure.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the medial Achilles tendon island flap with a modified Kessler suture to the distal tendon

Results

In all cases the patients scored good or excellent over-all satisfaction with the surgical procedure performed. All tendons healed without complications. No infections, nerve injuries or reruptures occurred during or after surgery. The functional results for each patient are presented in Table 2. None of the patients reported limitations in ADL nor complained of pain from the injured leg. One patient reported persistent post-activity swelling of the leg and three out of nine patients reported slight calf muscle weakness not affecting daily life activities. All patients reported normal walking function also on stairs, but one patient had reduced endurance in heel raising. The post-surgery activity level is also presented in Table 2. In three patients the activity levels were reduced to long walks but the other patients had returned to various recreational activities they had enjoyed prior to the primary injury.

Table 2.

Patient reported outcome

| Case | ADL | Pain | Calf muscle weakness | One leg standing | Heel raising | Walking | Walking in stairs | Running | Physical exercise | Patient’s satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Normal | None | Some | Normal | Good | Normal | Normal | Yes | Sports | Good |

| Case 2 | Normal | None | None | Normal | Good | Normal | Normal | No | Sports | Good |

| Case 3 | Normal | None | None | Normal | Week | Normal | Normal | No | Sports | Excellent |

| Case 4 | Normal | None | None | Normal | Good | Normal | Normal | Yes | Walks | Good |

| Case 5 | Normal | None | None | Normal | Good | Normal | Normal | Yes | Sports | Excellent |

| Case 6 | Normal | None | Some | Normal | Good | Normal | Normal | No | Walks | Good |

| Case 7 | Normal | None | None | Normal | Good | Normal | Normal | No | Sports | Excellent |

| Case 8 | Normal | None | None | Normal | Good | Normal | Normal | Yes | Sports | Excellent |

| Case 9 | Normal | None | Some | Normal | Good | Normal | Normal | Yes | Walks | Good |

ADL activities of daily life

Discussion

In this case series with nine consecutive patients operated upon for either neglected Achilles tendon rupture or rerupture of the Achilles tendon using a novel technique with a medial Achilles tendon island flap we demonstrate high patient satisfaction and good long-term patient-reported functional results without surgical complications. Compared to other surgical techniques this method has a fairly limited surgical approach, it respects the neuro-vascular anatomy of the calf and reduces the bulk of tissue inserted to the rupture site, and we believe these circumstances are important to minimise the risk for wound healing problems.

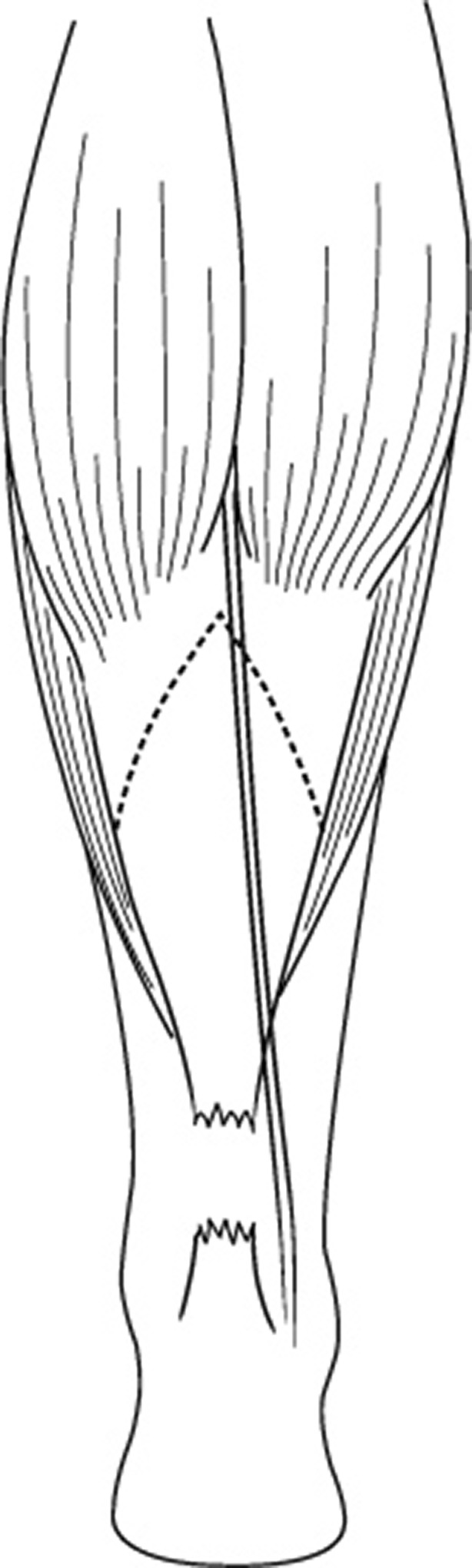

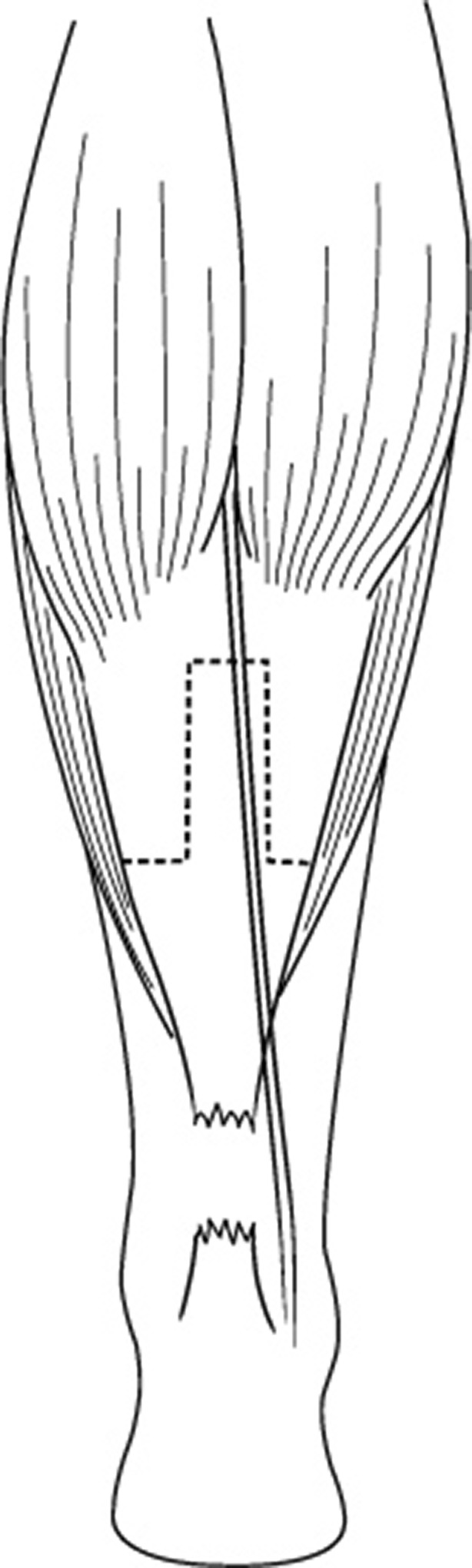

A number of different surgical techniques for treatment of neglected ruptures and reruptures of the Achilles tendon are described in the literature. Three methods, the V-Y tendon alignment (Fig. 2) [8], the tongue-in-groove recession (Fig. 3) [12] and our technique with a medial Achilles tendon island flap (Fig. 1), could be defined as island flaps, which in these circumstances signify a tendon transfer where the blood supply has been preserved to the tendon graft. The V-Y tendon alignment [8] achieves an end-to-end sutured anastomosis of the rupture site by an inverted V-shaped incision of the gastrocnemius aponeurosis and repairs it in a Y-shaped fashion. In a similar way, the tounge-in-groove recession [12] creates a distal advancement of the proximal tendon end, allowing an end-to-end suture of the rupture. The principal difference between these three methods of island flaps is that the V-Y tendon alignment and the tounge-in-groove recession advance a full proximal tendon end down to the distal tendon while our new method advances half of the proximal tendon width to the distal tendon. In our experience, this difference in technique, with less bulky graft advanced to the rupture site, reduces the risk of skin tension and subsequent wound healing problems.

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of the incision (dotted line) for the V-Y tendon alignment

Fig. 3.

Schematic illustration of the incision (dotted line) for the tounge-in-groove recession

From a scientific point of view therefore there are no evidence-based guidelines for selection of the optimal technique for reconstruction of these Achilles tendon injuries [13]. Compared to the surgical treatment of acute Achilles tendon injuries, reconstruction of neglected ruptures and reruptures are associated with an increased risk of complications [11], and special attention to avoid wound healing problems including infections is necessary. Surgical methods preserving the blood supply to the graft, to the Achilles tendon area and to the overlaying skin could therefore be favourable to methods using free tissue or tendon transfer.

The main vascular supply of the Achilles tendon enters from the anterior paratenon from which vessels run into the tendon. The proximal part of the tendon is supplied through a recurrent branch of posterior tibial artery and the distal part of the tendon is supplied through rete arteriosum calcaneare, connected to the posterior tibial artery and to the fibular artery [14]. If surgical dissection anterior to the proximal part of the tendon is avoided we believe this recurrent vascular supply of the proximal part of the tendon is preserved which makes this area of tissue, used in an island flap, suitable for distal advancement in the surgery of reruptured Achilles tendons and neglected Achilles tendon ruptures.

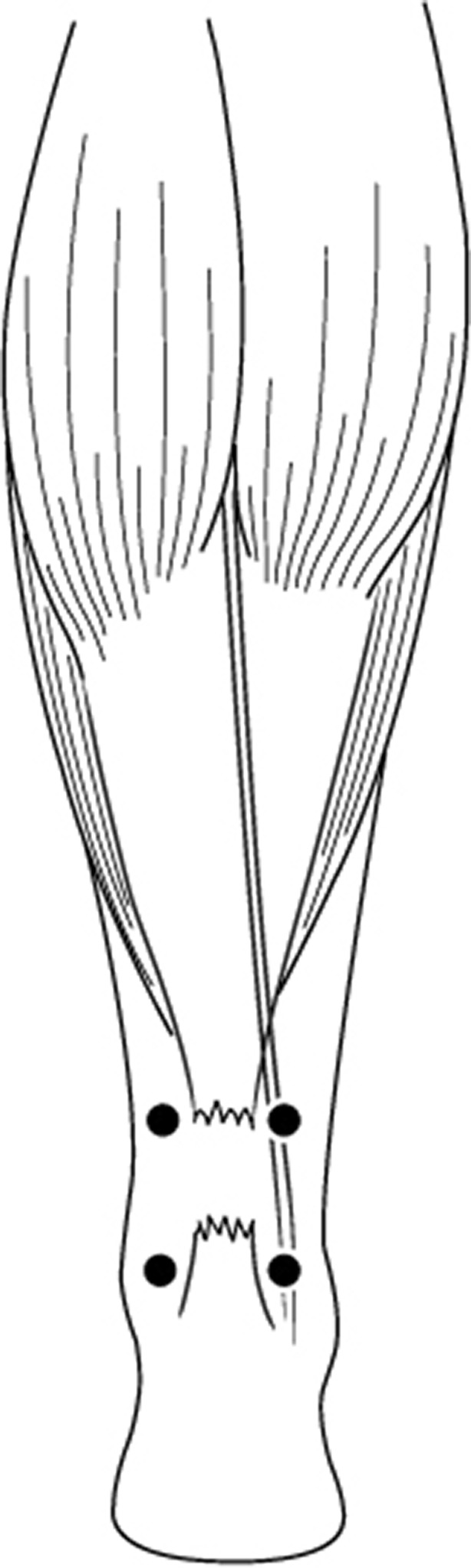

The neuro-vascular structures of importance for skin survival over the Achilles tendon area include the small saphenous vein, the superficial sural artery and the sural nerve, all running longitudinally above the deep fascia (Fig. 4). Close to gastrocnemius myotendinous junction, this neurovascular bundle goes from the midline to run on the lateral aspect of the Achilles tendon. From the sural artery several cutaneous branches raise to the skin and more distally, behind the lateral malleolus, the sural artery anastomoses with the peroneal artery. This neuro-vascular bundle is potent enough to carry a large skin flap on a reverse pedicle retained from the perforator proximal to the lateral malleolus and can be used for covering soft tissue defects of the distal third of tibia and the foot [15]. Jeng et al. [16] also used this technique to cover exposed Achilles tendons and soft tissue defects of the ankle and the heel. Injuring this neuro-vascular bundle in the repair of Achilles tendon injuries puts the skin survival at risk, potentially causing devastating wound healing problems. All surgical methods crossing the midline to the lateral side on the proximal gastrocnemius aponeurosis such as V–Y tendon alignment [8], tongue-in-groove advancement [12], free gastrocnemius flap [3] or turnover flaps [5] involve a certain risk to this neurovascular structure. Most techniques also place the skin incision on the medial side to avoid this complication. Also the perforators (just above the malleolus) (Fig. 4) are crucial to the blood supply of the skin and should be protected during the surgery, their anatomical location with a close proximity to both peroneus brevis and flexor hallucis brevis [17] is a potential risk when performing tendon transfers.

Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration of the neurovascular anatomy at risk during surgery: four important perforating vessels; neurovascular bundle including the sural nerve, the small saphenous vein and the superficial sural artery

Several different turn-down flaps have been used in order to bridge the tendon gap in neglected ruptures. Christensen et al. [18] were the first to describe this technique in 1931. Later, Arner and Lindholm [19] modified the technique and used two flaps instead of one, while Silfverskiöld [6] used one rotated flap in order to ensure that the smooth tendon surface faced the skin and to reduce the risk of skin adhesions. The use of a turn down flap has also been described in combination with a V to Y lengthening in six patients [20]. The functional results of these techniques appears to be acceptable but the major drawback from our point of view is the large bulky mass of tissue over the rupture site causing an increased tension to the overlying skin and subsequent wound healing problems. This is possibly true also for different types of flap augmentation. Gerdes et al. [2] showed that flap augmentation produced better pull-out strength than end-to-end sutures alone but the increase in strength when adding more tissue to the rupture site needs to be balanced against the risk of wound problems, especially in patients with an obvious retraction of the skin over the rupture site. End-to-end sutures alone have been recommended if the resected tendon gap is less than 2.5 cm [11], and for V-Y tendon alignment there has been concern of tearing of the muscle during elongation when covering gaps greater than 4–5 cm [21]. In our experience, there are limited intraoperative problems covering a tendon gap up to 5–6 cm with the medial Achilles tendon island flap just by applying a gentle but consistent traction to the proximal tendon island. In three patients the rupture gap was even greater (7–8 cm) but still possible to cover with this method. The end-to-end sutures have not shown failure or elongation and no reruptures occurred although our case series also included patients with compromising co-morbidity.

The use of tendon transfers, including peroneus brevis [22], flexor digitorum longus [23] and flexor halluces longus [24, 25], has been reported in several studies in the treatment of chronic Achilles tendon ruptures as well the use of free tendon grafts, including fascia lata [26], gracilis [7] and more recently using a gastrocnemius aponeurosis flap [3]. Maffulli et al. [7] presented good results using a free gracilis tendon graft in 21 patients, who had a chronic rupture of the Achilles tendon. Their conclusion was that this was a technically demanding yet safe procedure, although it resulted in reduced strength and decreased ankle motion. Most recently Nilsson-Hellander et al. [3] evaluated a single incision technique (which has some similarities to our method) using a free gastrocnemius aponeurosis flap in 28 consecutive patients with a chronic rupture of the Achilles tendon. With this technique good functional results were reported with only one deep infection.

The presence of a visible skin retraction over the rupture site is in our experience one of the main problems in treating non-acute ruptures of the Achilles tendon since the reconstruction of the tendon inevitably will cause an increased tension to the skin, compromising the vascular supply to the skin and possibly leading to a wound break-down. Maffuli et al. [11] have solved this issue by not incising the tendon gap, instead using shorter incisions proximal and distal to the rupture site when performing a reconstruction of the tendon using peroneus brevis. This is certainly attractive from a wound healing perspective but apart from the technical difficulties with this method the author points out the risk for sural nerve injury in this minimally invasive procedure. We have found our method with the medial Achilles tendon island flap to be very suitable in these patients by using a less bulky repair and thereby reducing the tension to the skin. The method is simple with a short learning curve and could therefore be adopted by orthopaedic surgeons who are not dedicated to foot and ankle surgery.

We acknowledge several limitations with this study. First, the low number of patients and the retrospective design limits the overall conclusion of this report. Second, objective long-term assessment of the patients is missing and functional results are only presented with patient reported subjective data and without using validated instruments, such as the Achilles tendon total rupture score (ATRS) [27]. Nevertheless, we believe this report highlights some important anatomical and technical aspects in treating patients with chronic Achilles tendon ruptures. Despite several complicating co-morbidities we achieved good patient reported outcome without surgical complications. We find this surgical method advantageous compared to other more complex techniques described in the literature.

The authors are grateful to Dag Månsson in Stockholm who created the illustrations.

References

- 1.Jiang N, Wang B, Chen A, Dong F, Yu B (2011) Operative versus nonoperative treatment for acute Achilles tendon rupture: a meta-analysis based on current evidence. Int Orthop. Dec 9 [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1431-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Gerdes MH, Brown TD, Bell AL, Baker JA, Levson M, Layer S. A flap augmentation technique for Achilles tendon repair. Postoperative strength and functional outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;280:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsson-Helander K, Swärd L, Grävare Silbernagel K, Thomeé R, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J. A new surgical method to treat chronic ruptures and reruptures of the Achilles tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:614–620. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0492-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen I. Rupture of the Achilles tendon; analysis of 57 cases. Acta Chir Scand. 1953;106:50–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindholm A. A new method of operation in subcutaneous rupture of the Achilles tendon. Acta Chir Scand. 1959;117:261–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silfverskiöld N. Uber die subcutane totale Achillessehnenruptir und deren Behandlung. Acta Chir Scand. 1941;84:393–413. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maffulli N, Leadbetter WB. Free gracilis tendon graft in neglected tears of the Achilles tendon. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15:56–61. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000152714.05097.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham E, Pankovich AM. Neglected rupture of the Achilles tendon. Treatment by V-Y tendinous flap. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:253–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneppendahl J, Thelen S, Schek A, Bala I, Hakimi M, Grassmann JP, Eichler C, Windolf J, Wild M (2011) Initial stability of two different adhesives compared to suture repair for acute Achilles tendon rupture—A biomechanical evaluation. Int Orthop. Sep 21 [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1357-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Kissel CG, Blacklidge DK, Crowley DL. Repair of neglected Achilles tendon ruptures—procedure and functional results. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1994;33:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maffulli N, Ajis A. Management of chronic ruptures of the Achilles tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1348–1360. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker RG, Repinecz M. Neglected rupture of the Achilles tendon. Treatment by modified Strayer gastrocnemius recession. J Am Podiatry Assoc. 1979;69:548–555. doi: 10.7547/87507315-69-9-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leslie HD, Edwards WH. Neglected ruptures of the Achilles tendon. Foot Ankle Clin. 2005;10:357–370. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zantop T, Tillmann B, Petersen W. Quantitative assessment of blood vessels of the human Achilles tendon: an immunohistochemical cadaver study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123:501–504. doi: 10.1007/s00402-003-0491-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masquelet AC, Romana MC, Wolf G. Skin island flaps supplied by the vascular axis of the sensitive superficial nerves: anatomic study and clinical experience in the leg. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:1115–1121. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199206000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeng SF, Wei FC. Distally based sural island flap for foot and ankle reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:744–750. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199703000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor GI, Palmer JH. The vascular territories (angiosomes) of the body: experimental study and clinical applications. Br J Plast Surg. 1987;40:113–141. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(87)90185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christensen I (1931) To tilfaelde af subcutan Achillesseneruptur. Dansk Kir Sels Forh 75(39)

- 19.Arner O, Lindholm A. Subcutaneous rupture of the Achilles tendon; a study of 92 cases. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1959;116:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Us AK, Bilgin SS, Aydin T, Mergen E. Repair of neglected Achilles tendon ruptures: procedures and functional results. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1997;116:408–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00434001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rush JH. Operative repair of neglected rupture of the tendo Achillis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1980;50:420–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1980.tb04156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez Teuffer A. Traumatic rupture of the Achilles tendon. Reconstruction by transplant and graft using the lateral peroneus brevis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1974;5:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mann RA, Holmes GB, Jr, Seale KS, Collins DN. Chronic rupture of the Achilles tendon: a new technique of repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wapner KL, Pavlock GS, Hecht PJ, Naselli F, Walther R. Repair of chronic Achilles tendon rupture with flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer. Foot Ankle. 1993;14:443–449. doi: 10.1177/107110079301400803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wegrzyn J, Luciani JF, Philippot R, Brunet-Guedj E, Moyen B, Besse JL. Chronic Achilles tendon rupture reconstruction using a modified flexor hallucis longus transfer. Int Orthop. 2010;34:1187–1192. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0859-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bugg EI, Jr, Boyd BM. Repair of neglected rupture or laceration of the Achilles tendon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;56:73–75. doi: 10.1097/00003086-196801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nilsson-Helander K, Thomeé R, Grävare Silbernagel K, Thomeé P, Faxen E, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J. The Achilles tendon Total Rupture Score (ATRS): development and validation. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:421–426. doi: 10.1177/0363546506294856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]