Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of our study is to make a retrospective evaluation of endoscopic treatment of Haglund’s syndrome using a new three portal technique.

Methods

All 23 patients (25 heels) with a mean age of 27.7 years were evaluated pre-operatively and postoperatively with parallel pitch lines, the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score and the Ogilvie Harris score.

Results

The mean follow-up was 41 months (range, 30–59 months). There were no obvious complications in our study. In 22 heels, postoperative lateral radiographs showed the achievement of negative parallel pitch lines. The average AOFAS score improved from 63.3 ± 11.9 points pre-operatively to 86.8 ± 10.1 points at final follow-up. There were 14 excellent results, seven good results, two fair results and two poor results. For the Ogilvie Harris score, there were 15 excellent, seven good, one fair, and two poor results.

Conclusion

An endoscopic procedure using the three portal technique seemed to be a safe and efficacious option for surgical treatment of Haglund’s syndrome.

Introduction

A calcaneal prominence associated with pain in the retrocalcaneal region is called Haglund’s syndrome [1], which has been recognized as a cause of posterior heel pain [2, 3]. Repetitive squeezing of the retrocalcaneal bursa at dorsal flexion of ankle, resulting from impingement between the posterosuperior prominence of the calcaneus and the anterior aspect of the Achilles tendon, can sometimes cause painful bursitis and insertional Achilles tendinopathy. A variety of procedures for treatment of Haglund’s syndrome including nonoperative and operative methods are in use. Operation is used after failure of nonoperative treatment for more than six months. Surgical treatment involves removal of the posterosuperior prominence of the calcaneus and the inflamed retrocalcaneal bursa [4].

Currently, open surgical correction of a calcaneal prominence has been a widely accepted approach for treating Haglund’s syndrome. Numerous authors have reported substantial postoperative improvements with different outcome measures [3, 5, 6]. However, open surgical treatment is associated with several complications including skin breakdown, Achilles tendon avulsion [7], altered sensation [8], and stiffness.

To avoid these problems associated with the open surgical technique, the endoscopic technique is an up-and-coming procedure. The accuracy and precision of this procedure have been confirmed [4, 9, 10]. Van Dijk et al. [11] reported on 20 patients with substantial increases in outcome measures using a two portal endoscopic approach to the retrocalcaneal space at a mean 3.9-year follow-up. Minor complications with endoscopic treatment are reported.

Because endoscopic treatment for Haglund’s syndrome is a new procedure and experience is limited, modification of endoscopic techniques has continued to evolve, aiming to avoid complications and improve outcome.

This study describes a new three portal technique providing access to the retrocalcaneal space, enabling sufficient observation of the posterosuperior region of pathology of the calcaneus and allowing adequate endoscopic bony resection. We propose that this three portal technique is a reliable and efficient option for the endoscopic treatment of Haglund’s syndrome.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Between January 2007 and June 2009, endoscopic management of Haglund’s syndrome was performed on 25 feet in 23 patients. The study included six males (six heels) and 17 females (19 heels) with a mean age of 27.7 years (range, 17–41 years). All patients experienced symptoms for the mean of 14.9 months (range, ten to 24 months) prior to the operation.

The presence of Haglund’s syndrome was diagnosed by the clinical symptoms, physical examination, plain radiographs, and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRI).

Typical presentation involved pain, local swelling, and stiffness in the hindfoot. In all patients, a bony prominence was palpated at the region of the posterosuperior part of the calcaneus. Pain was reproduced with palpation just lateral and medial to the Achilles tendon at the level of posterosuperior calcaneal prominence, but without tenderness of the Achilles tendon itself.

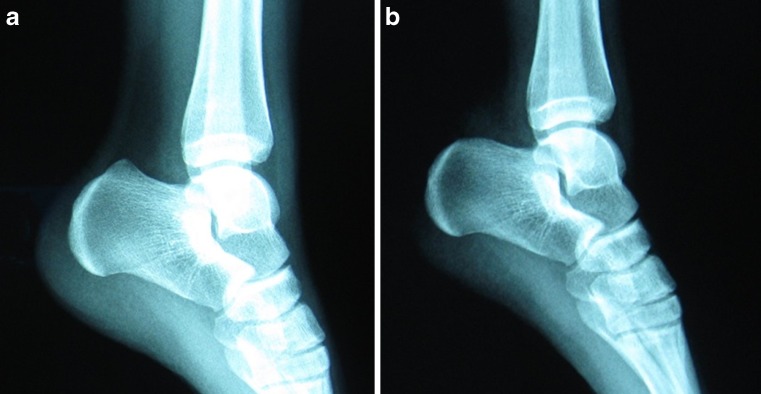

Pre-operatively, lateral radiograph and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRI) of ankle were obtained in all patients. The lateral radiographs (Fig. 1a) demonstrated a remarkable posterosuperior calcaneal prominence with positive parallel pitch lines [12] in all patients. Also, the MRI showed a retrocalcaneal bursa with inflammation and swelling.

Fig. 1.

a Pre-operative lateral radiograph illustrated remarkable posterosuperior calcaneal prominence. b Postoperative lateral radiograph illustrated complete resection of bony prominence

All patients failed to respond to nonsurgical treatment for more than six months. Nonsurgical treatment included avoidance of tight shoes, the use of orthotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, activity modification, and physical therapy. Steroid injections were not used because of the risk of Achilles tendon rupture and, in some cases, unwillingness to try.

We excluded patients with any surgery on the affected ankle, calcific insertional Achilles tendinpathy, partial or full rupture of Achilles tendon, cavus foot, varus foot, and posterior heel pain resulting from rheumatoid arthritis.

Surgical Technique

The endoscopic procedure was performed with the patient in the prone position under lumbar anaesthesia. A tourniquet was applied at the thigh. The affected foot was positioned over the distal border of the operation table. Dorsiflexion of the foot was controlled by the surgeon’s body.

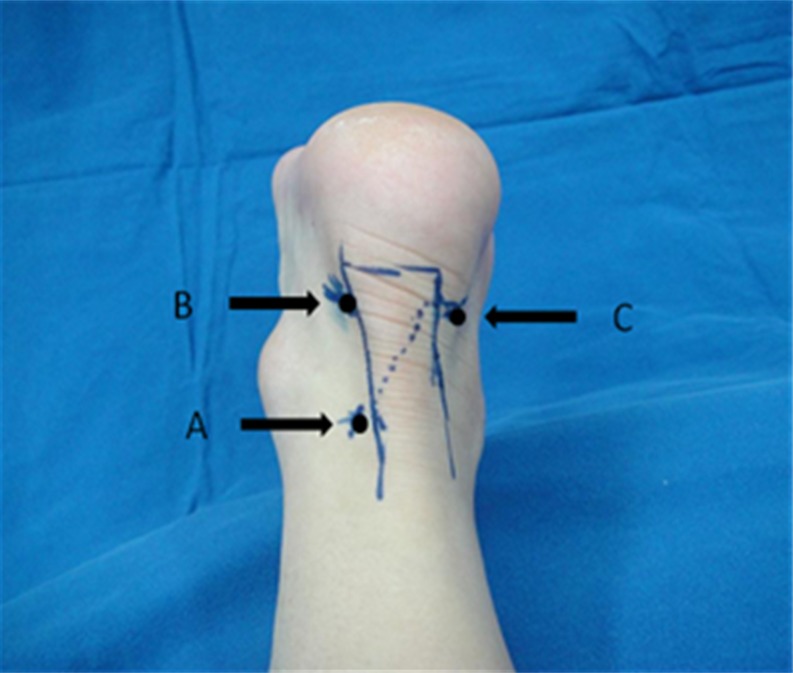

A proximal posterolateral portal (PPLP) (Fig. 2) was first established directly lateral to the Achilles tendon and 5-cm proximal to the Achilles tendon insertion. A 0.5-cm long vertical incision was made through the skin. Care was taken to incise only the skin, and the subcutaneous tissue was spread with a mosquito clamp with ease. Then a blunt trocar was inserted distally to the retrocalcaneal space. After blunt dissection of the adipose tissue anterior to the Achilles tendon, a 4-mm, 30° endoscope was introduced to the retrocalcaneal space. The inflamed retrocalcaneal bursa was then identified.

Fig. 2.

Portal Placement. a Proximal posterolateral portal (PPLP). b Distal posterolateral portal (DPLP). c Distal posteromedial portal (DPMP)

To make two distal portals—a distal posteromedial portal (DPMP) (Fig. 2) and a distal posterolateral portal (DPLP) (Fig. 2)—a spinal needle was inserted directly adjacent to the Achilles tendon at the level of the superior aspect of the calcaneus under direct visualization. Instruments were introduced through the DPMP or the DPLP and visualized through the proximal posterolateral portal (PPLP). To have a better visualization, the excision of inflamed retrocalcaneal bursa was performed using a 4-mm shaver (Smith-Nephew, Andover, MA) through the DPMP. If necessary, excision was done again through the DPLP.

The full view of the posterosuperior calcaneal prominence was mainly acquired by endoscopy through a single portal—the PPLP. Under direct endoscopic supervision, it was found that fibrous cartilage covering the calcaneal prominence and the anterior aspect of the Achilles tendon formed a joint-like structure. And the impingement location was determined when the foot was maximally dorsiflexed.

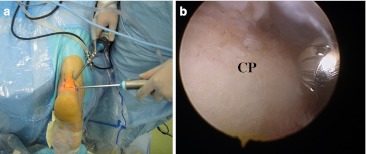

Under direct observation, a bur (Smith-Nephew, Andover, MA) was inserted through the DPMP or DPLP (Fig. 3a,b) to perform the calcaneoplasty with the foot maximally plantar flexed. The medial part of the calcaneal prominence was removed with the bur inserted from the DPMP and the lateral part was done with the bur from the DPLP. Two distal portals were interchanged for the bur to perform adequate bony resection. The extent of bony resection was judged dynamically with the ankle moving through a full range of motion. Elimination of impingement in maximal dorsiflexion of the foot indicated adequate removal of bone. During the procedure of calcaneoplasty, the closed side of the bur was against the Achilles tendon to prevent damage to the tendon.

Fig. 3.

a The 4-mm, 30° endoscope was introduced from the proximal posterolateral portal (PPLP) and a 4-mm bur inserted through the distal posterolateral portal (DPLP). b Intra-operative photograph shows the bur was placed on the calcaneal prominence (CP)

Direct inspection of the Achilles tendon insertion was undertaken with the foot fully plantar flexed. Debridement of the Achilles tendon was performed with the Vapor (Arthrocare, Sunnyvale, CA) for a yellowish discolouration. Finally, the shaver was used to smooth the incisal surface of the calcaneus and remove the loose tissue. The portals were closed with a single 3-0 monocryl suture.

Postoperative Care

Postoperatively the patient was encouraged to perform elevation of the foot for the first week along with range-of-motion exercises. Partial weight bearing was performed for the first two weeks with gradual full weight bearing in the third week. Conventional footwear was not allowed to be worn during the first eight weeks. And physical activities should not be performed for three months.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were evaluated with the parallel pitch lines, the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score and the Ogilvie Harris score pre-operatively and at final follow-up. On the basis of the postoperative AOFAS score, the outcome was rated as excellent (90–100), good (80–89), fair (70–79), or poor (<70) [13].

The difference in pre-operative AOFAS score and that evaluated at final follow-up was analysed by using Wilcoxon two-sample test, with P < 0.05 to determine significance. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software (version 15.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

No patients were lost to follow-up, and the average follow-up was 41 months (range, 30–59 months). In all patients, the bony prominence and the inflamed retrocalcaneal bursa were found under the endoscopic view. In six feet, a yellowish discolouration in the region of the Achilles tendon insertion was present, which has been histologically described as a chondroid metaplasia [10]. However, partial or full rupture of the Achilles tendon was not found.

The mean surgical time was 40 minutes in the initial 12 heels (range, 32–45 minutes), whereas the average time for the following cases was 30 minutes (range, 20–38 minutes).

None of the patients was converted to open surgery. In 22 heels, postoperative lateral radiographs (Fig. 1b) showed achievement of adequate bony removal and negative parallel pitch lines. In three heels, parallel pitch lines were still positive. The average AOFAS score improved from pre-operatively 63.3 ± 11.9 points to 86.8 ± 10.1 points at final follow-up (P < 0.0001). There were 14 excellent results, seven good results, two fair results and two poor results. For the Ogilvie Harris score, there were 15 excellent, seven good, one fair, and two poor results. And two poor outcomes in the AOFAS score and the Ogilvie Harris score were from the same patient with the bilaterally affected heel. That occurred due to an anterior cruciate ligament injury of his right knee in the second year postoperatively.

There were no permanent neurovascular injuries and no wound infections related to the three portal technique. In one heel, redness and swelling of the incision in the distal posteromedial portal (DPMP) was found and resolved after removal of the stitches.

Discussion

Open surgical treatment is a well-accepted method of treatment for Haglund’s syndrome and yields good to excellent results in short and midterm follow-ups [6, 14–16]. Pećina [16] performed open resection of the calcaneal tuberosity in 16 active athletes. All athletes returned to full training programs and continued competing. However, this operation is associated with complications including skin breakdown, Achilles tendon avulsion [7], altered sensation [8] and stiffness. Endoscopic therapy for Haglund’s syndrome has become a promising alternative. Several authors reported their two portal endoscopic techniques and substantial postoperative increases in different outcome measures [4, 9, 10].

However, the two portal technique seems to have difficulty in acquiring convenient manipulation simultaneously with excellent view of the calcaneal prominence. Switching portals should be repetitively done to ensure that sufficient medial and lateral bony calcaneal prominence is removed. Moreover, the small distance between posteromedial portal and posterolateral portal [4, 9, 10] causes the inconvenience of endoscopic manipulation, which increases the risk of injuring the instruments and structures and leads to prolongation of operation time.

To acquire full view of the pathological posterosuperior calcaneal region, enlarge the space for endoscopic manipulation, and minimize the risk of iatrogenic lesions, we adopt a three portal technique. Compared with the two portal technique advocated by Van Dijk et al. [11], a new proximal posterolateral portal (PPLP) is placed just lateral to the Achilles tendon and 5-cm proximal to the Achilles tendon insertion. The PPLP is predominantly used as a viewing portal. The PPLP seems to have a larger distance to the calcaneal prominence than the distal portals, which provides us full view. Because of the greater distance, it seems that the endoscope can “overlook” the calcaneal prominence and thereby provide us a general view. Acquiring full view of the prominence through a single portal is conducive to predicting the amount of bony resection. And then the distal posteromedial portal (DPMP) and the distal posterolateral portal (DPLP) would be safely made under direct endoscopic control without any injury to the Achilles tendon and calcaneus. But a proximal posteromedial portal was not applied for preventing damage to the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle [17]. There was no incidence of damage to skin, nerve and Achilles tendon in our study. All patients showed no signs of neurovascular dysfunction, and there were no cases of infection or bleeding. The satisfactory results of our study indicated the safety and feasibility of the three portal technique.

There is still a controversy over the amount of bony resection in calcaneoplasty. Both under resection and overresection of calcaneal prominences can result in surgical failure in calcaneoplasty. Nesse and Finsen [18] confirmed that bony under resection is a vital reason why the posterior heel pain persists postoperatively. However, bony over resection places patients at great risks of lesion of the Achilles tendon insertion and calcaneus fracture [4]. Various radiographic measurements are used to judge the extent of the required bony correction [12, 19–21]. But there is absence of a perfect radiographic measurement [6, 8, 14, 22]. In our study, the amount of the required bony resection was confirmed by using a dynamic endoscopic examination. In three feet, their postoperative parallel pitch lines were still positive, but they are satisfied with the endoscopic outcomes and have good results in the AOFAS score and the Ogilvie Harris score at final follow-up. Given their findings, we believe that the proximal posterolateral portal provides better direct visualization of the posterior calcaneal region, allowing us to thoroughly explore adequate elimination of impingement and sufficient removal of bone in a dynamic manner.

There are still some limitations in our study. The first is the lack of a control group , the second is the small number of subjects, and the short follow-up. Controlled study and larger patient series are needed to verify whether our three portal technique will improve the results, although our reported results are promising. Lastly, a longer follow-up is necessary to determine whether endoscopic treatment for Haglund’s syndrome with the three portal technique may persist in symptomatic relief and perform adequate bony resection instead of insufficient resection or excessive resection.

Contributor Information

Yinghui Hua, Email: hua023@hotmail.com.

Shiyi Chen, Email: cosm.chen@gmail.com.

Reference

- 1.Haglund P. Beitrag zur Klinik der Achillessehne . Zeitschr Orthop Chir. 1928;49:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiamengo SA, Warren RF, Marshall JL. Posterior heel pain associated with a calcaneal step and Achilles tendon calcification. Clin Orthop. 1982;167:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johannes IW, Aimee CK, Dijk CN. Surgical treatment of chronic retrocalcaneal bursitis. Arthroscopy. 2012;2:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dijk CN, Dyk CE, Scholten PE, Kort NP. Endoscopic calcaneoplasty. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;2:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVries JG, Summerhays B, Guehlstorf DW. Surgical correction of Haglund’s triad using complete detachment and reattachment of the Achilles tendon. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;48:447–451. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sella EJ, Caminear DS, McLarney EA. Haglund’s syndrome. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1998;2:110–114. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(98)80089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le TA, Joseph PM. Common exostectomies of the rearfoot. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1991;8:601–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauker M, Katz K, Yosipovitch Z. Calcaneal osteotomy for Haglund’s disease. J Foot Surg. 1992;31:558–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortmann FW, McBryde AM. Endoscopic bony and soft-tissue decompression of the retrocalcaneal space for the treatment of Haglund deformity and retrocalcaneal bursitis. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;2:149–153. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jerosch J, Schunck J, Sokkar SH. Endoscopic calcaneoplasty (ECP) as a surgical treatment of Haglund’s syndrome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:927–934. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dijk CN, Dyk GE, Scholten PE, Kort NP. Endoscopic calcaneoplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2001;2:185–189. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290021101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavlov H, Heneghan MA, Hersh A, Goldman AB, Vigorita VT. The Haglund’s syndrome: initial and differential diagnosis. Radiology. 1982;1:83–88. doi: 10.1148/radiology.144.1.7089270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hua YH, Chen SY, Li YX, Chen JW, Li H. Combination of modified Broström procedure with ankle arthroscopy for chronic ankle instability accompanied by intra-articular symptoms. Arthroscopy. 2010;4:524–528. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jardé O, Quenot P, Trinquier-Lautard JL, Tran-Van F, Vives P. Haglund disease treated by simple resection of calcaneus tuberosity. An angular and therapeutic study. Apropos of 74 cases with 2 years follow-up. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1997;6:566–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sammarco GJ, Taylor AL. Operative management of Haglund’s deformity in the nonathlete: a retrospective study. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;11:724–729. doi: 10.1177/107110079801901102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pećina MM, Bojanić I. Overuse injuries of the musculoskeletal system. 2. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2003. pp. 270–273. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton WG. Surgical anatomy of the foot and ankle. Clin Symp. 1985;37(3):2–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nesse E, Finsen V. Poor results after resection for Haglund’s heel. Analysis of 35 heels in 23 patients after 3 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65:107–109. doi: 10.3109/17453679408993732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fowler A, Philip JF. Abnormalities of the calcaneus as a cause of painful heel: its diagnosis and operative treatment. Br J Surg. 1945;32:494–498. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18003212812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chauveaux D, Liet P, Huec JC, Midy D. A new radiologic measurement for the diagnosis of Haglund’s deformity. Surg Radiol Anat. 1991;13:39–44. doi: 10.1007/BF01623140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh R, Rohilla R, Siwach RC, Magu MK, Sangwan SS, Sharma A. Foot (Edinb) 2008;18:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angermann P. Chronic retrocalcaneal bursitis treated by resection of the calcaneus. Foot Ankle. 1990;10:285–287. doi: 10.1177/107110079001000508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]