Abstract

Rehabilitation following hip arthroscopy can vary significantly. Existing programs have been developed as a collaborative effort between physicians and rehabilitation specialists. The evolution of protocol advancement has relied upon feedback from patients, therapists and observable outcomes. Although reports of the first femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) surgeries were reported in the 1930’s, it was not until recently that more structured, physiologically based guidelines have been developed and executed. Four phases have been developed in this guideline based on functional and healing milestones achieved which allow the patient to progress to the next level of activity. The goal of Phase I, the protective phase, is to progressively regain 75% of full range of motion (ROM) and normalize gait while respecting the healing process. The primary goal of Phase II is for the patient to gain function and independence in daily activities without discomfort. Rehabilitation goals include uncompensated step up/down on an 8 inch box, as well as, adequate pelvic control during low demand exercises. Phase III goals strive to accomplish pain free, non-compensated recreational activities and higher demand work functions. Manual muscle testing (MMT) grading of 5/5 should be achieved for all hip girdle musculature and an ability to dynamically control body weight in space. Phase IV requires the patient be independent with home and gym programs and be asymptomatic and pain free following workouts. Return to running may be commenced at the 12 week mark, but the proceeding requirements must be achieved. Athletes undergoing the procedure may have an accelerated timetable, based on the underlying pathology. Recognizing the patient’s pre-operative health status and post-operative physical demands will direct both the program design and the program timetable.

Keywords: Femoroacetabular impingement, Hip arthroscopy, Rehabilitation guidelines, Return to sport

Introduction

The clinical entity of Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) is not a new concept. It was first described in the late 19th century in Germany and later in the 1930’s in the United States. However Murray in the UK was the first to describe it as an etiology of hip arthritis and this was further elucidated by Professor Ganz in the U.S. [1–3]. FAI is an abnormal abutment of the proximal femur against the rim of the acetabulum causing limitation of motion and has been implicated as a pathomechanical process causing early hip dysfunction, chondro-labral injuries, and ultimately hip arthritis [1, 3]. The etiology of FAI is multifactorial and can be posttraumatic, the sequelae of pediatric disease or idiopathic in nature. Idiopathic FAI can result from a decrease in femoral head-neck offset (cam effect), an overgrowth of the bony acetabulum or acetabular retroversion (pincer effect), or a combination of these deformities. During hip flexion, the abnormal contoured femoral head engages the anterosuperior acetabulum and produces shear forces that lead to chondral abrasion, delamination and eventually, full-thickness cartilage loss. The natural history of this impingement process is initially acetabular cartilage injury, which is followed by labral injury and ultimately joint arthrosis.

Although treatment options for FAI vary considerably, arthroscopic approaches have grown in popularity in recent years. Its main utility was in the treatment of labral and chondral lesions but recent innovations have enhanced the ability of hip arthroscopy to perform femoral osteochondroplasties and acetabular rim resections [4, 5]. Using modern arthroscopic techniques, hip arthroscopy can achieve similar results as an open surgical dislocation, which is considered by many the “Gold Standard” for FAI surgery [5, 6, 11]. The advantages of arthroscopy are that it is a minimally invasive ambulatory procedure that does not require a trochanteric osteotomy [7]. Furthermore, arthroscopy allows for a dynamic, intraoperative assessment and correction of the offending lesions. Although initially met with skepticism, the early results of arthroscopic treatment of FAI have reported favorable outcomes. A recent systematic review reported 67–100% good-to-excellent short-term clinical outcomes after arthroscopic treatment of hip impingement [8••].

The long-term viability of arthroscopic hip surgery, however, is predicated upon meticulous intraoperative evaluation and a thorough and accurate correction of impingement lesions on both the femoral and acetabular side. It is a procedure which demands a high degree of technical proficiency with a steep learning curve [9]. Failure of arthroscopic techniques for FAI is most commonly associated with incomplete decompression of the associated bony anatomy [10]. Besides inaccurate or inadequate decompression, there are numerous other pitfalls associated with FAI surgery. There are more basic issues which include indications, positioning, cannulation, and visualization as well more advanced issues such as the decision to perform labral resection vs. repair, the role of different labral repair techniques and finally, how best to handle the anterior capsule—capsular sparring, capsulotomy +/-repair, capsulectomy, capsular reefing, etc.[9].

Although there are numerous surgical pitfalls, it has also been recognized that an equally important aspect of arthroscopic FAI is proper postoperative rehabilitation [8••]. Depending on the exact nature of the procedure, rehabilitation can vary tremendously. This article will highlight the various protocols and guidelines of postoperative hip arthroscopy after FAI surgery.

Rehabilitation guidelines

As the arthroscopic options available to patients with non-arthritic hip pain continue to evolve, the postoperative rehabilitation protocols associated with such procedures have progressed as well. A number of articles have been published discussing postoperative rehabilitation protocols [12–17, 18•]. Most postoperative protocols are based upon basic tissue healing properties, patient tolerance, and clinicians’ experience [12–17, 18•]. At this time, minimal evidence-based literature exists regarding the specific topic of postoperative rehabilitation.

The majority of available protocols primarily focus on the rehabilitation of individuals following surgery to address tears of the acetabular labrum (resection or repair procedures). A subset of the articles address rehabilitation concerns for procedures to address conditions such as femoral acetabular impingement (FAI), capsular laxity, and tissue release procedures (iliopsoas and/or iliotibial band), and small to medium-sized chondral lesions. Enseki et al. [16•] and Wahoff [18•] described principles for those patients undergoing osteoplasty to address FAI [16•, 18•]. Of particular concern for these individuals, is controlling the weight bearing progression early during the rehabilitation process. Range-of-motion (ROM) precautions have been suggested for individuals undergoing procedures to address capsular laxity of the hip (thermal modification or plication) [13, 17]. In the case of tissue release procedures, avoidance of early initiation of long-lever hip flexion (iliopsoas release) or abduction (iliotibial release) is suggested [13, 17]. In cases undergoing microfracture procedures to address chondral lesions, weight bearing restrictions have been described [13, 15].

The majority of existing protocols share common principles in terms of initial exercises, weight bearing, ROM, and strength recommendations. All guidelines suggest initiating early, protected ROM. Utilization of an upright stationary bike (seat set relatively high, minimal resistance) for gentle ROM is consistently recommended by the available guidelines. The utilization of gentle circumduction ROM for the hip joint has been suggested early in the rehabilitation process [14, 18•]. Stretching of hip and pelvic musculature as indicated and tolerated, is universally recommended by the available guidelines. With the possible exceptions of the previously described procedures of osteoplasty and microfracture, the most commonly prescribed recommendation is foot flat/30 lbs. pressure for up to 4 weeks. All guidelines suggest early utilization of general strengthening for the hip, thigh, and pelvic musculature. Gluteus medius strength is consistently emphasized across the guidelines. Singleton and Stalzer et al. describe specific exercises on a time-line [14, 15]. Though variable depending on specific procedure and individual patient characteristics, guidelines most often suggest a minimum period of approximately 12 weeks before initiating a return to athletic or other strenuous activities (exceptions may apply in rare cases) [13–15].

As the surgical options available to individuals with pathological conditions of the hip joint evolve, concurrent postoperative rehabilitation protocols must change to reflect the demands of the population undergoing such procedures. Rehabilitation has progressed to not only address tears of the labrum, but also the associated conditions of FAI, capsular laxity, and chondral lesions. With the topic of non-arthritic hip pain becoming a more popular topic in the orthopedic literature, an emphasis should be placed upon the development of postoperative rehabilitation programs that are supported by evidence-based practice.

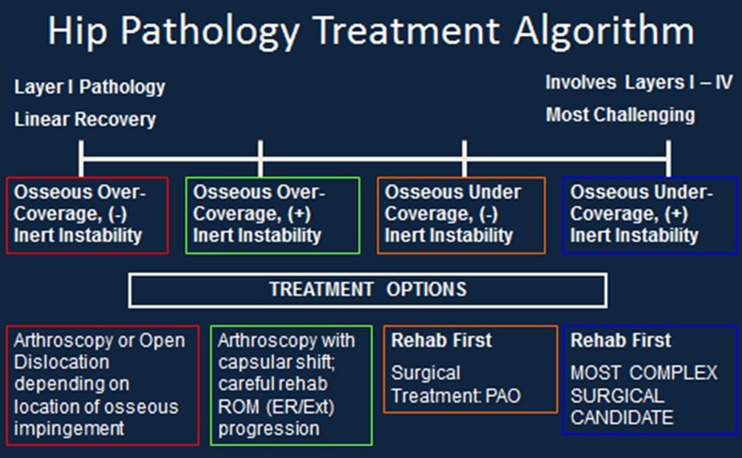

The following postoperative guidelines have been developed based on a sliding scale of functional progression. Clinical experience has demonstrated that variations in osseous structure, inert tissue laxity and neuromuscular control greatly affect the timeline of recovery. As a result, we have devised an algorithm to demonstrate this concept (Fig. 1). Those individuals with more osseous generated pathology with good inert structural stability and neuromuscular control will progress more quickly (Linear) than those individuals who have a more complex combination of osseous abnormalities as well as decreased inert stability (laxity) and poor neuromuscular control and timing (Complex). At this time our data does not yet demonstrate a significant correlation to the chronicity of the injury or the gender of the individual. The headings below will be marked Linear and Complex referring to the patient type. Four phases have been developed in this guideline based on functional and healing milestones achieved which allow the patient to progress to the next level of activity.

Fig. 1.

Hip Pathology Treatment Algorithm

Phase I post-operative guidelines (linear: 0–4 weeks/complex: 0–6 weeks)

Following hip arthroscopy, the patients are seen in physical therapy postoperative day 1. The orders from the physician most often relate to a procedure involving a femoral osteochondroplasty, an acetabular rim trimming and a repair or debridement of the labrum. In these situations the initial weight bearing status is 20% foot-flat weight bearing for two weeks. The exception being if there has been a microfracture procedure or a gluteus medius repair, the 20% weight bearing restriction will be extended to 6 weeks. There are generally no ROM restrictions unless a capsular repair or a psoas release has been performed. However there is caution not to push the range of motion to a point of discomfort either with exercise or in daily activities. Patients are advised to avoid sitting on low soft surfaces, not to pivot over the leg, not to cross their legs, not to walk for exercise, and not to lift the operative leg on its own. Depending on the physician, some patients go home with a Continuous Passive Motion (CPM) machine and a hip brace (Bledsoe Philippon Post-Operative Hip Brace, Bledsoe Brace Systems, Grand Prairie, TX, USA). The CPM is used for 3 weeks and the brace for 10 days.

Communication with the physician is imperative in knowing what the surgical procedure entailed. Most importantly, was the capsule closed versus shifted to increase stability. If a capsular shift was performed, external rotation will be limited from 0° to 30° and extension limited to 0° for the first 6 weeks. If a psoas release was performed, active hip flexion is restricted for 6 weeks and significant care must be taken through the rehabilitation process in educating and strengthening hip flexion. A microfracture procedure warrants weight bearing to be restricted 6 weeks versus 2 weeks. If extra-articular procedures were performed concomitantly with the arthroscopic procedure, including a gluteus medius repair, there will be protection against active hip abduction and passive hip adduction for 6 weeks. Concomitant pelvic floor pathologies must also be considered. In such cases, active external rotation is often restricted for 4–6 weeks to avoid tone and spasm of the obturator internus muscle, which has been demonstrated to exacerbate pelvic floor pain [19].

Phase I is the protective phase. (Table I) The goal is to reduce lower extremity edema, gently progress hip range of motion and regain normal neuromuscular firing patterns of the pelvis and hip. Manual skills and soft tissue mobilization are an essential component to a successful recovery. Soft tissue work to reduce edema in the quadriceps and hamstrings is utilized post-operative day one. As the patient progresses over the next 2 weeks, soft tissue mobilization focuses on the adductor group, which tends to quickly develop tone. Research has demonstrated that the adductor longus acts as a hip flexor and abductor and the adductor magnus acts as a hip extensor [20]. Clinically, it appears while other pelvic and hip stabilizers are inhibited due to pain or neuromuscular dysfunction, the adductors are often the first muscle group to compensate. Following hip arthroscopy, the psoas muscle is often inhibited. The patient is unable to progress the affected leg in gait or lift the leg in transfers. Clinically, the tensor fascia lata and rectus femoris are superficial hip flexors which tends to compensate for the lack of function of the psoas and become overused and irritated during the post-operative course. These muscles in addition to the gluteus medius and minimus all benefit from soft tissue mobilization to reduce tone throughout the rehabilitation process.

A short crank bicycle is initiated on the first post-operative day and is quickly progressed to a regular bicycle. The patients are encouraged to work up to 20 min on a bike four to six times a week. For those individuals using a CPM at home, one 20 min session on the bike is counted for 1 h and a half session on the CPM. The purpose of the bike is to encourage gentle motion through the joint and again facilitate lubrication of the joint and nutrients via the synovial fluid [21]. If any stress is felt in the hip flexors, we educate pedaling in an even circumferential motion, making sure the contralateral side is being used to assist.

Isometric exercises for the transversus abdominus, quadriceps and gluteals are also initiated during the first session. Lastly, a series of passive range of motions by the therapist is performed. These physiological movements never bring the range to the point of an anatomical boundary or into pain. The supine motions include hip flexion, internal and external rotation at 30° hip flexion, abduction at 15° hip flexion and circumduction, clockwise and counter-clockwise at 15° of hip flexion. The patient is then placed in prone over a pillow and passive motion into internal rotation and external rotation is performed as well as a gentle rectus femoris stretch via knee flexion. The pillow is removed as tolerated to allow a gentle stretch of the anterior hip.

The goals for Phase I are to normalize the gait pattern without the use of an assistive device and achieve 80% of full range of motion. The requirements for a normalized gait are to have no notable Trendelenberg or Modified Trendelenberg, full hip extension from mid-stance to toe off and normal progression of the extremity through swing phase such that the pelvis is not rotating forward in either the coronal or transverse plane to facilitate lower extremity advancement. This is achieved by slowly regaining full range of motion through active assistive exercises for hip flexion in quadruped and rotation on a stool; and progressive exercises emphasizing dynamic stability of the core hips and pelvis. This is initially generated through the upper extremities for core stabilization and through closed chain co-contraction exercises for the lower extremity. The use of hydrotherapy in retraining gait and weight acceptance is very effective once the incisions are healed. Lastly, proprioceptive exercises in bilateral stance are initiated as soon as weight bearing restrictions are lifted.

Phase II post-operative guidelines (linear: 4–8 weeks/complex: 6–12 weeks)

The goal for Phase II is for the patient to achieve independence in daily activities with little or no discomfort. Ultimately, the patient should be able to ambulate for extended distances, reciprocate 8 inch steps up and down with good pelvis and hip control as identified by level positioning of the pelvis through the activity (no hip drop or compensating trunk lean) and no forward trunk flexion. Additionally the patient should be able to functionally squat down and carry moderate weights, i.e. School bag, work bag, groceries and household chore items, without difficulty.

This is achieved through continued manual work to address soft tissue restrictions at end ranges of motion and progressive work to address neuromuscular control, timing and strength. Clinically, muscular tissue and fascial networks are addressed and cleared of all restrictions prior to addressing the joint capsule. Mobilization of the joint capsule without definitive objective findings and reasoning may be detrimental to the patient’s recovery.

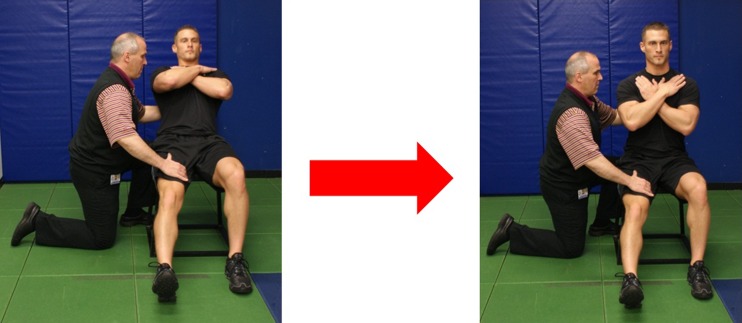

Re-education of the psoas may be initiated during Phase II. Historically, there has been much discussion over the primary function of the psoas [22, 23] as a hip flexor or a lumbar stabilizer. Following hip arthroscopy, patients often present with the psoas muscle inhibited. This is demonstrated by difficulty in performing hip flexion and an inability to control hip extension through stance phase of gait. As a result, these patients may begin to develop a hip flexor tendinitis. Not necessarily of the psoas, however more often of the secondary hip flexors including the tensor fascia lata, rectus femoris and sartorius. Clinical experience has demonstrated it to be most effective to re-educate psoas from the trunk down versus the leg up. The results have thus far been successful, in that the patients regain full hip flexion strength without developing tendinitis of the psoas or the secondary hip flexors. Re-educating the psoas during Phase II has been found to be most effective by using an eccentric exercise developed at this institution (Fig. 2). The patient is seated and the therapist provides support to the trunk while palpating the quadriceps and adductors with the other hand. The patient is instructed to hinge back from the hip, maintaining a stable lumbar spine. The psoas is being activated during the lower movement and then the therapist assists the trunk movement back up to neutral. Assessing the ease and comfort level of standing hip flexion prior to and following the exercise is of importance because the response is immediate.

Fig. 2.

Eccentric Psoas Training

The timing of gluteal function must be assessed and addressed early in the rehabilitation process. Cowen identified Australian football players with a history of groin pain as demonstrating loss of the feed forward mechanism of the transversus abdominus [24]. Bullock-Saxton et al. [25] demonstrated a change in muscle firing patterns of the gluteals versus the hamstrings in elite soccer following chronic ankle sprains whereby the gluteals fired after the hamstrings during prone hip extension versus within the normal parameters of the feed forward time frame as described by Hodges [26, 27]. This faulty firing pattern reduces the stabilization capabilities of the gluteals at the hip and potentially allows for more anterior translation and levering of the femoral head during hip extension activation of the hamstrings. This same faulty firing pattern is seen in patients with hip pain and following hip surgery. Therefore, care must be taken to re-educate the firing pattern prior to initiating any dynamic and loaded activity. This may be accomplished by having the patient lie prone and re-educate transversus firing, then gluteal firing, followed by a small hip extension motion with care being taken not to allow the activity to over-ride the core stabilizers as indicated by lumbar extension or pelvic rocking.

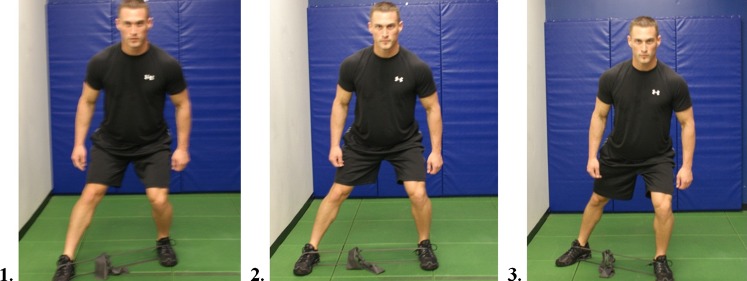

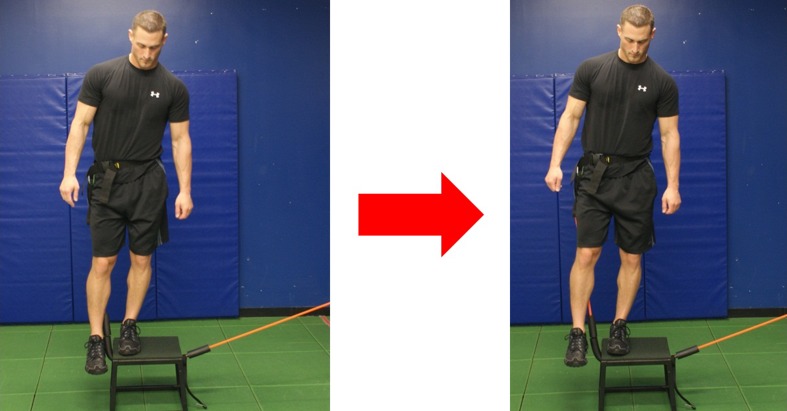

Once the timing is improved this may be carried over to additional gluteal strengthening and pelvic and hip stabilizing exercises. Distefano et al. [28] demonstrated with electromyographic studies, exercises which promote effective gluteus medius and maximus activity. According to their study gluteus medius demonstrated the most effective activation with side lying abduction, single limb squat, lateral band side stepping, single limb deadlift and sideways hops. Effective activities for gluteus maximus firing are single limb squat and single limb deadlift. These types of exercises are effective during the Phase II of rehabilitation; however considering that the study was done with healthy subjects, care must be taken in using long lever open chain exercise in a population with hip pathology. A supine straight leg raise can increase compressive forces across the joint. Reizbos [29] demonstrated joint compressive forces to be 250% body weight when performing side lying hip abduction with 5 kg weight attached to ankle. This would be nearly equivalent to performing a closed chain single leg squat. Phase II is the time to progress from closed chain bilateral dynamic stability exercises to unilateral exercises. Examples include forward step downs, three point stepping with elastic band, windmill, and lawnmower. (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Three Point Step with Elastic Band

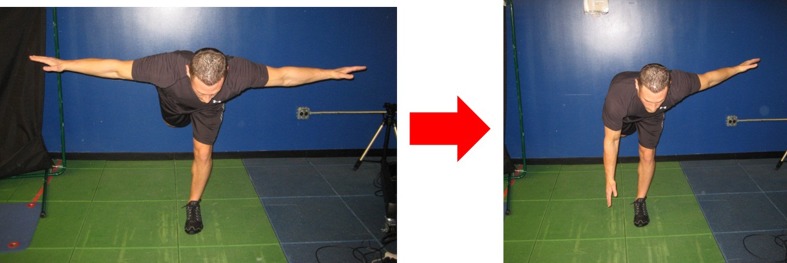

Fig. 4.

Windmill: Stance leg is the affected leg. Alternating arm movements creates dynamic stability over the loaded hip

Criteria to advance from Phase II to Phase III is based on no pain with daily activities, full hip range of motion to meet the demands of their activities, core stabilization at a minimum of a Sahrmann [30] Level 2 for 30 s, normalized gluteal timing, 5/5 manual muscle strength in the affected leg, good neuro-muscular control demonstrated in a single leg squat and 8” step up and step down.

Phase III post-operative guidelines (linear: 8–12 weeks/complex: 12–20 weeks)

The primary goal of Phase III is to become recreationally asymptomatic. This phase of the program looks to build both strength and endurance, precursors to being able to functionally control one’s own body weight in space. The patient should also be able to maintain core control during all components of their activities. The patient will need periodic tactile and verbal cueing for both trunk stabilization and body position awareness, especially when they begin to fatigue. Continuing to emphasize extremity motion on a stable core should remain a major focal point. Manual muscle testing in this phase should test for multiple repetitions to assess for muscle endurance. Likewise, careful observation during functional exercise should be assessed for fatigue or compensatory movements. The exercise should be ceased if proper form cannot be maintained. Quality should not be sacrificed for quantity.

Treatment recommendations of this phase are to increase both volume and intensity of aerobic activity, regardless of the equipment choice. Core training volume and intensity is also increased during this phase. Core exercises initiated during this phase may include kneeling cable crossovers, T position side supports, T position eye of the needle, side support rowing, side support hip abduction, front support leg raises and kneeling chops/lifts, for example. Lower extremity work may include a modified body weight (BW) lunge routine, BW sumo squats to 90° knee flexion, cable squats, Flexband push press-military-overhead squats-sidestep snatches, high box step ups and progressing to elastic band running form hip flexion, lawn mowers (Fig. 5), hip hikes with tubing resistance (Fig. 6) and elastic band split squats (Fig. 7). Proprioception continues on varying surfaces as well as manipulating eyes open and closed positions, with and without perturbations [31]. Half foam roll steamboats and standing tubing lifts engage the proprioceptive system [31]. Range of motion should be checked periodically to ensure that loading the hip with new exercises does not altered neuromuscular response and normal joint mechanics. Plyometrics may begin with in place jumps and agility ladder. Flexibility should include dynamic warm-up routine, and side lying runner’s position stretch, scorpion if necessary, and sport specific stretches. Finally, an appropriate soft tissue and recovery program should be instituted as the person prepares to return to competitive sport.

Fig. 5.

Lawn Mower: Unilateral stabilization over the operated leg against resistance moving from hip flexion to neutral hip extension

Fig. 6.

Hip Hiking with Tube Resistance: The stance leg is the stabilized leg requiring ipsilateral gluteals and pelvic stabilizers to control motion

Fig. 7.

Elastic Band Split Squats: The band pulls the extremity into adduction forcing control and focus on abductor and external rotator strength

Prior to initiating a plyometric program it is recommended that a person be able to squat 150% BW [32]. If the person has not done barbell squats, one may use 1.5 x BW leg press. Prior to commencing running, though not examined in literature, the person should be able to asymptomatically perform the “10 Rep Triple.” This includes 10 front step downs without kinetic collapse, 10 single leg squats without kinetic collapse and 10 side lying leg raises against resistance with MMT score of at least 4/5 for all repetitions without compensation.

Phase IV post-operative guidelines (linear: 12–16 weeks/complex: 20–28 weeks)

The primary goal of Phase IV is not only to return to a pain free competitive state, but also to avoid both breakdown and any type of an acute inflammatory response during the process. This requires a phased and progressive program that errs to the side of caution. Although both evidenced based and empirical clearing tests for return to sport exist [18• 33–35] it is important to note, that regardless of the pathology, a competitive person will never feel completely recovered until they can consistently and painlessly repeat the movement responsible for the mechanism of injury. This phase must be micromanaged to a degree, since the person will be the most active as they have been in months. The provider must be able to effectively control a rehabilitation maintenance program, practice schedule, skill work and strength and conditioning training sessions without causing a setback. The program must include all components of training that improve explosive power. Training variables such as high velocity strength, slow velocity strength, inter-muscular coordination and skill, stretch shortening cycle, rate of force development [36], and technique must be incorporated to any late phase program. Manipulating one exercise variable per session will offer the greatest chance of avoiding a setback [37]. The program in this phase should incorporate all planes of motion, integrate working proximal to distal and distal to proximal, work in both a controlled and uncontrolled environment and combine the exercise variables of repetition, positional holds/controlled movement, function and sport specific speed. Repetition work insures recruitment, overload and strength. Positional holding and controlled movement accounts for postural stability and muscular endurance. Function assures patterning and technique while speed activities ensure the person is safely generating force for their activity without compromise.

Once the athlete is at the end of their rehabilitation or transition program and about to begin pre-season camp, it is strongly suggested that rest time be built into the schedule. Clinical experience has demonstrated initiating all camp activities may lead to a setback. Summer sport skill camp in late phase rehabilitation, is not recommended, unless participation can be adequately monitored and adjusted. Performing the speed plane work as the work session closest to the competitive date is recommended, since it should be a lower volume of work and performed at a higher intensity.

Conclusion

Rehabilitation following hip arthroscopy will not always be predictable when multiple layers of tissue are involved. The clinician must remember that initially during the process it is prudent to check joint mobility after each loading episode. It is also important to recognize that there will be a soft tissue accommodation period following FAI surgery. Discriminating between tissue tightness and increased tone will also help to direct treatment. Understanding the motion contributions of each segment of the kinetic link will assist in program design. Healing times will vary considerably based on which osseous or soft tissue structures were involved. It is not uncommon for athletes to recover more quickly than the average person, even though all patients are most at risk for setbacks when transitioning from one phase of rehabilitation to the next. Another common mistake is when multiple exercise variables are manipulated during a single session. Since hip rehabilitation is not linear, having a good understanding of the underlying pathology and the goals of the patient combined which skilled clinical reasoning and patience is essential.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Contributor Information

Jaime Edelstein, Phone: +1-917-3439887, FAX: +1-212-7742089, Email: edelsteinj@hss.edu.

Anil Ranawat, Phone: +1-646-7978700, FAX: +1-646-7978777.

Keelan R. Enseki, Phone: +1-412-4323700, FAX: +1-412-4323750, Email: ensekikr@upmc.edu

Richard J. Yun, Email: yunr@hss.edu

Peter Draovitch, Phone: +1-212-6061005, FAX: +1-212-7742089, Email: draovitchp@hss.edu.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, et al. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:264–272. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray RO. The aetiology of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. Br J Radiol. 1965;38:810–824. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-38-455-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, et al. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417:112–120. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096804.78689.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrd JW, Jones KS. Arthroscopic femoroplasty in the management of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:739–746. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0659-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sussmann PS, Ranawat AS, Lipman J, Lorich DG, Padgett DE, Kelly BT. Arthroscopic versus open osteoplasty of the head-neck junction: a cadaveric investigation. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganz R, Gill TJ, Gautier E, et al. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:1119–1124. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B8.11964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford JR, Villar RN. Current concepts in the management of femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1459–1462. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B11.16821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedi A, Chen N, Robertson W, et al. The management of labral tears and femoroacetabular impingement of the hip in the young, active patient. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Logishetty K, Bedi A, Ranawat AS. The role of navigation and robotic surgery in hip arthroscopy. Oper Tech Orthop. 2010;20:255–263. doi: 10.1053/j.oto.2010.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyworth BE, Shindle MK, Voos JE, et al. Radiologic and intraoperative findings in revision hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1295–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leunig M, Ranawat AS, Ganz R. Surgical hip dislocation for femoroacetabular impingement. Tech Hip Arthro Joint Pres Surg. 2011;28:228–239. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4160-5642-3.00028-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin KM, Henry CO, Byrd JWT. Rehabilitation after hip arthroscopy. J Sport Rehabil. 2000;9:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enseki KR, Martin R, Draovitch P, et al. The hip joint: arthroscopic procedures and postoperative rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:516–525. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stalzer S, Wahoff M, Scanlan M. Rehabilitation following hip arthroscopy. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25:337–57. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singleton SB. Rehabilitation after arthroscopy of an acetabular labral tear. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2007;2:241–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enseki KR, Martin R, Kelly BT. Rehabilitation after Arthroscopic Decompression for Femoroacetabular Impingement. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29:247–55. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enseki KR, Draovitch P. Rehabilitation for Hip Arthroscopy. Oper Tech Orthop. 2010;20:278–281. doi: 10.1053/j.oto.2010.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahoff M, Ryan M. Rehabilitation after hip femoroacetabular impingement arthroscopy. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30:463–82. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prather H, Dugan S, Fitzgerald C, et al. Review of anatomy, evaluation, and treatment of musculoskeletal pelvic floor pain in women. PM R. 2009;1:346–358. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green DL, Morris JM. Role of the adductor magnus and adductor longus in postural movements and in ambulation. Am J Phys Med. 1970;49:223–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nugent-Derfus GE, Takara T, O’Neill JK, et al. Continuous passive motion applied to whole joints stimulates chondrocyte biosynthesis of PRG4. Osteoarthritis Cart. 2007;15:566–574. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santaguida PL, McGill SM. The psoas major muscle: a three-dimensional geometric study. J Biomech. 1995;28:339–345. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)00064-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersson EA, Oddsson L, Grundstrom H, et al. The role of the psoas and Iliacus muscles for stability and movement of the lumbar spine, pelvis and hip. Scan J Med Sci Sports. 1995;5:10–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1995.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowan SM et al. Delayed onset of transversus abdominus in long-standing groin pain. Med Sci Sports Exer 2004;2040–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Bullock-Saxton JE, Janda V, Bullock M. The influence of ankle sprain injury on muscle activation during hip extension. Int J Sports Med. 1994;15:330–334. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine. 1996;21:2640–2650. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199611150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Contraction of the abdominal muscles associated with movement of the lower limb. Phys Ther. 1997;77:132–144. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Distefano LJ, Blackburn JT, Marshall SW, et al. Gluteal muscle activation during common therapeutic exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:532–540. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riezebos C, Lagerberg A. Overbelasting (Overuse Dutch) Versus, Tijdschrift voor fysiotherapie. 2000;18:21–60. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes. St. Louis: Mosby Inc; 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blacburn JT, Reimann BL, Myers JB, et al. Kinematic analysis of the hip and trunk during bilateral stance on firm, foam, and multiaxial support surfaces. Clin Biomech. 2003;18:655–661. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0033(03)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kutz MR. Theoretical and practical issues for plyometric training. NCSA PT J. 2003;2:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1968–1978. doi: 10.1177/0363546510376053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Handling K, Rylander R: Return to sport field test. University of Delaware, 1985.

- 35.Myer GD, Schmitt LC, Brent JL, et al. Utilization of modified NFL combine testing to identify functional deficits in athletes following ACL reconstruction. JOSPT. 2011;41:377–388. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newton RU, Kraemer WJ. Developing explosive muscular power: implications for a mixed methods training strategy. Strength Cond. 1994;16:20–31. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gambetta V. Athletic development. Champaign: Human Kinetics Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]