Abstract

We examine the association between late-stage breast cancer diagnosis and residential poverty in Detroit, Atlanta, and San Francisco in 1990 and 2000. We tested whether residence in census tracts with increasing levels of poverty were associated with increased odds of a late-stage diagnosis in 1990 and 2000 and found that it was. To test this, we linked breast cancer cases from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer registries with poverty data from the census. Tracts were grouped into low, moderate, and high poverty based on the percentage of households reporting income below the poverty level. While late-stage breast cancer rates and the number of women living in high and moderate-poverty areas declined absolutely between 1990 and 2000, estimates from our combined three-city model showed that odds of a late-stage diagnosis remained stubbornly elevated in increasingly poor areas in both years. Non-Hispanic black women faced higher odds of a late-stage diagnosis relative to non-Hispanic white women in both years. In separate regressions for each city, the odds ratios affirm that combining data across cities may be misleading. In 1990 and 2000, only women living in moderately poor neighborhoods of San Francisco faced elevated odds, while in Detroit women in both moderate- and high-poverty areas faced increased likelihood of late-stage diagnosis. In Atlanta, none of the poverty measures were significant in 1990 or 2000. In our test of physician supply on stage, an increase in the number of neighborhood primary care doctor’s offices was associated with decreased odds of a late-stage diagnosis only for Detroit residents and for non-Hispanic whites in the three-city model.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Poverty, Physician location, Access to care

Background

Living in high poverty and in economically distressed areas in Detroit, San Francisco, and Atlanta put women at significantly elevated risk of late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in 1990.1,2 While high poverty—defined as census tracts with at least 40% of households in poverty—rose nationally between 1980 and 1990, it declined substantially between 1990 and 2000. There was a 74% decline in the number of people living in high-poverty (>40% in poverty) tracts in Detroit by 2000, with a 61% decline in San Francisco, and a 1% decline in Atlanta.3 Transformed by positive growth, in-migration to major urban centers, better wages, improved labor and housing markets, many of the poorer areas within these three cities experienced economic improvement.3,4

Yet poverty persisted at historically high levels in 2000, especially among African Americans, and there was a rapid increase in concentrated affluence at the top.5 A large literature has established that neighborhood poverty exerts an independent effect on health, including breast cancer diagnostic stage and survival.6,7 We consider whether a decade of declines in poverty levels made a difference in the likelihood of a late-stage breast cancer diagnosis for residents of poorer tracts. Specifically, we test whether residence in tracts with increasing levels of poverty were associated with greater odds of a late-stage diagnosis in 2000 as we had found in 1990.1

We also examine data on primary care doctor’s offices, available only in 2000, giving special attention to these findings for registry cases residing in Detroit. By 2000, regional economic improvements had contributed to declines in the number of people living in high poverty in Detroit.3,8 Yet, a spatial study by Grengs9 found that while poverty rates declined after 1990 in Detroit, concentrated pockets of high poverty remained very much in evidence. Another study by Swanstrom et al.10 using a relative definition of poverty based on 50% of median regional income rather than the absolute federal standard commonly used in the USA found smaller declines in high poverty for Detroit and for the nation than researchers who used the absolute poverty standard.

Early Detection of Breast Cancer

Mammography is an effective tool for detecting breast cancer early,11 and whether a woman receives an early- or later-stage diagnosis of breast cancer is strongly associated with use of mammography. Mammography in the USA most often is referred by a primary care physician during a routine care visit, making it essential for women to have access to primary care services in order to proceed to a mammography facility as well as to obtain results and follow-up care as needed.12,13 The strongest predictor of mammography use for individual women is access to primary care.14,15

In 2000, 77% of women aged 50–64 reported having had a mammogram within the previous 2 years.16 Poverty, race/ethnicity, and the spatial distribution of healthcare resources are important determinants of both mammography use and breast cancer stage disparities. Despite significant improvements in screening rates across all racial/ethnic groups, African-American women were still more likely to receive later-stage breast cancer diagnoses between 1990 and 1998.17 Poorer, less-educated women, and those without health insurance or a usual source of care are less likely to be screened for breast cancer.16,18

The literature shows that women living in poor areas are at especially high risk of not getting cancer screening.19–21 Early-stage breast cancers are generally detected by mammography and access to physician services is the primary predictor for getting a timely mammogram.22 Not having a usual source of care is associated with both low mammography rates and late-stage diagnosis, especially for low-income and racial–ethnic minorities.23,24 The only study on the impact of physician supply on breast cancer stage in the USA found no relation between overall physician supply and stage of breast cancer diagnosis; however, greater numbers of primary care doctors did increase the likelihood of early-stage detection.25

City-specific case studies provide further evidence on determinants of screening and stage disparities. In Chicago, neighborhood economic distress and socioeconomic improvement in poorer areas were both independently associated with later-stage disease.26 Gumpertz et al.7 found a higher risk of advanced disease in Los Angeles for black women living in areas where incomes and educational attainment were low. African-American residents in poorer areas of Chicago had longer travel distance to access low or no-fee mammography facilities than other residents.27

Data and Methods

We compare 1989–1990 breast cancer cases in three US cities, San Francisco, Atlanta, and Detroit with cases from 1999 to 2000. We chose these three Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) metropolitan areas for our original study because they are characterized by large differences in socioeconomic status among residents, the existence of both high and low-income areas, and racially and ethnically diverse populations. We do not have direct information on individual screening utilization.

Study Population

For both the initial 1989–1990 study and the 1999–2000 comparison, we linked breast cancer cases from the SEER cancer registries in the three cities with selected area-level socioeconomic status data from the census (1990 and 2000 US Census Bureau summary files, STF3 and SF3, respectively). Registry records provide information on place of residence at time of diagnosis, age, race, marital status, ethnicity, and stage at diagnosis. Cases with an unknown stage at diagnosis were excluded from our analysis: 7% (1,003/14,339) in 1989–1990 and 3% (588/19,497) in 1999–2000. Also excluded were subjects with unknown race: 1% (207) of 14,339 cases in 1989–1990 and 1% (191) of 19,497 cases in 1999–2000. SEER data are derived from medical abstracts and do not include measures of socioeconomic status.

To examine socioeconomic status, we linked individual SEER cases to the poverty level of the census tract where they lived at their time of diagnosis. Excluded were 5% (734) of the cases in 1989–1990 and 1% (220) in 1999–2000, which could not be linked in this way. Also excluded were 2% (400) of the cases in 1999–2000 which could not be matched to medically underserved area (MUA) designations from Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) because of missing or invalid census tract codes. All of the 1989–1990 cases were successfully matched to the MUA data. After these exclusions, our analysis is based on 12,395 registry cases in 1989–1990 and 17,582 cases in 1999–2000.

Variables

Our dependent variable, breast cancer diagnostic stage, was coded 1 if the diagnosis was late (stages 3B or 4), 0 otherwise. The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system, which is based on tumor size, nodal status, and metastases, was used to determine stage.28 We use census tract-level data to indicate residential poverty and compare breast cancer cases whose poverty level is defined by their tract of residence.

Census tracts were grouped into low, moderate, and high poverty based on the percentage of households reporting income below the poverty level. Bishaw29 provides the rationale for the use of these three poverty categories for both 1990 and 2000 census tracts. Tracts where less than 20% of the population lived in poverty were defined as low-poverty areas, tracts where 20–39% of the population lived in poverty were defined as moderate-poverty areas, and tracks where 40% or more of the population lived in poverty were defined as high-poverty areas. These area measures of residential poverty are based on the average income of all households in a tract, and may or may not characterize individual women living there.

We obtained data on the census tract location of primary care physician offices for all three cities in 2000 and matched them to 2000 SEER cases by census tract of residence. The data on primary care physician offices were obtained from a proprietary database generated by the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City (ICIC).30 The ICIC health establishment data defines an economic unit that produces goods or services at a single physical location and is engaged in one activity.1 ICIC used a city-specific template to map the number of primary care doctor’s offices located at the census tract level. We also appended to SEER cases a tract measure of MUA developed by HRSA. For HRSA to designate an area as MUA, local or state officials must have provided evidence that the area met specific HRSA thresholds for primary care providers, infant mortality, poverty, and elderly populations that demonstrated their inadequate medical resources.

Analysis Strategy

Our study uses registry cases taken from 1989 to 1990 and 1999 to 2000. We estimate the association between personal and ecological residential characteristics and stage at diagnosis using logistic regression analysis. To test whether the relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variables differed by year, we combined the data from the two time periods and included a dummy variable for the registry year. The time dummy measures the impact of the explanatory variables on late-stage diagnosis net of trends or aggregate conditions. We found significant time-interaction effects. Using the Chow test analog for logistic regression, we estimated the model by pooling 1990 and 2000 registry cases and then estimated by year separately. A joint likelihood ratio test on all differences did not allow us to reject the null hypothesis of no significant difference in the model between the 2 years (X2 = 28.887, df = 10; P = 0.0013).31 Therefore, the findings are examined separately by year. Small changes in the coefficient estimations presented in our earlier 1990 study1 from those presented here for 1990 are attributed to our use of three, instead of two, poverty level measures in this analysis, and to the elimination of the underclass variable from the 1990 estimations.

Since our previous study was published, research on all 11 SEER areas found that, between 1990 and 2001, Detroit registered the lowest breast cancer specific survival, as well as the second highest proportion of breast cancer patients with stage IV and unstaged.32 We therefore pay special attention to city-specific results from Detroit. For the 2000 analysis, we mapped ICIC data on doctors’ offices using ArcMap 9.2 and ArcGIS Desktop 9.2 software and we discuss them in light of our logistic regression findings.

Results

Table 1 shows the percentage of late-stage breast cancer diagnoses declined from 8% to 6% in the three SEER areas between 1990 and 2000. Between 1990 and 2000, the number of census tracts defined as high poverty, where 40% or more of the population lived in poverty declined from 4.15% (515/12,395) to just 1.35% (237/17,582) of all tracts. The percentage of moderate-poverty tracts also declined by 2000 from 9.84% (1,220/12,395) to 8.54% (1,501/17,582) of all tracts. In 2000, 90.11% (15,884/17,582) of total census tracts were defined as low poverty, up from 86% (10,660/12,395) in 1990. The table shows a decline in the proportion of cases identified as non-Hispanic white between 1990 and 2000 and an increase in the overall percentage of cases that resided in medically underserved areas. Detroit had the largest decline in the number of high-poverty tracts, from 8% of all tracts in 1990 to only 4.2% by 2000, and the greatest decline in the proportion of late-stage diagnoses (8.6–6.5%)

Table 1.

Characteristics of breast cancer cases: 1989–1990 and 1999–2000

| Variables | 1989–1990 | 1999–2000 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cities | San Francisco | Detroit | Atlanta | All Cities | San Francisco | Detroit | Atlanta | |||||||||

| N = 12,395 | N = 4,862 | N = 5,232 | N = 2,301 | N = 17,582 | N = 6,704 | N = 6,942 | N = 3,936 | |||||||||

| Percentage | SD | Percentage | SD | Percentage | SD | Percentage | SD | Percentage | SD | Percentage | SD | Percentage | SD | Percentage | SD | |

| Stage IIIB or IV | 7.9 | 7.5 | 8.6 | 7.4 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 6.5 | ||||||||

| Mean Age | 60.9 | 14.3 | 61.5 | 14.4 | 61.5 | 14.0 | 58.0 | 14.6 | 60.3 | 14.0 | 60.8 | 13.9 | 61.1 | 14.1 | 58.0 | 13.8 |

| Unmarried | 45.8 | 48.5 | 44.6 | 43 | 45.8 | 45.6 | 46.8 | 44.5 | ||||||||

| White (NH) | 79.4 | 77 | 81.7 | 79.6 | 73.2 | 69.4 | 78 | 71.3 | ||||||||

| Black (NH) | 14.6 | 8.9 | 17.6 | 19.6 | 16.7 | 8 | 20.5 | 25 | ||||||||

| Asian/PI (NH) | 3.2 | 7.8 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 6.3 | 14.6 | 1 | 1.6 | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 2.8 | 6.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 8 | 0.5 | 2.1 | ||||||||

| MUA | 9.7 | 10.5 | 9.2 | 9.3 | 15.6 | 14.3 | 16.8 | 15.7 | ||||||||

| Poverty 20–39% | 9.8 | 7.3 | 12.1 | 10 | 8.5 | 5.2 | 12.9 | 6.6 | ||||||||

| Poverty 40%+ | 4.2 | 0.5 | 8 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 2.2 | ||||||||

| Mean # of doctor offices | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6.2 | 17.5 | 6.8 | 17.8 | 4.2 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 26.3 | ||||

1989–1990 SEER and 1999–2000 SEER reporting areas for Atlanta, Detroit, and San Francisco; 1990 and 2000 Census Summary Tape File 3 and Summary File 3, respectively

Stage based on AJCC coding; cases missing MUA or stage are excluded

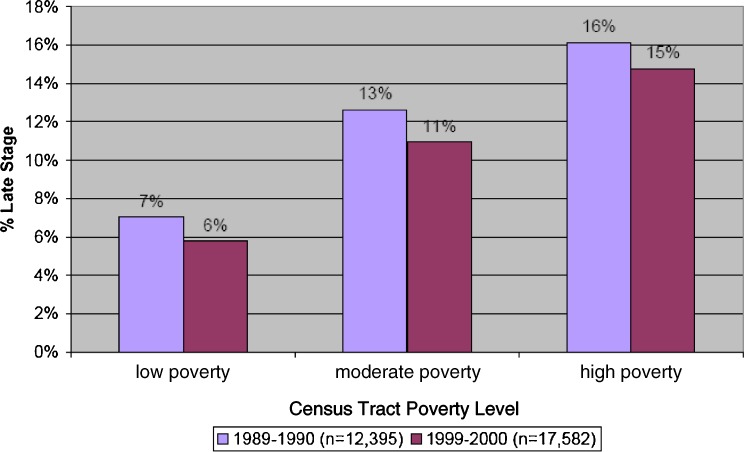

Figure 1 shows that women who resided in poorer areas were more likely to have a late-stage diagnosis both in 1990 and in 2000. The percentage of all cases diagnosed at a late stage increased in tandem with the residential poverty level. We had observed in 1990 that women diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer were more likely to reside in MUA, and this remained true in 2000 (data not shown). There were absolute improvements over the decade. In 1990, 16% of cases living in high-poverty tracts were late-stage diagnoses, but this fell to 15% in 2000. In 1990, 13% of cases living in moderately poor areas were diagnosed at a late stage, but this declined to 11% in 2000. In 1990, 7% of cases living in low-poverty areas were diagnosed at a late stage and, in 2000 it was 6%.

FIGURE 1.

Percent of all breast cancer cases living in poverty areas and diagnosed at a late stage 1989–1990 and 1999–2000.

Table 2 presents logistic regression estimates for the combined three-city model. In 1990, women residing in high-poverty areas had 70% greater odds of being diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer relative to women in low-poverty areas, and these odds were 80% in 2000. In 1990, women residing in moderate-poverty neighborhoods had 43% greater odds of a late-stage diagnosis relative to residents of low-poverty areas, with odds of 40% in 2000. Residence in an MUA was not significant in either year.

Table 2.

Odds of a late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in combined three-city model of San Francisco, Atlanta, and Detroit: 1990 and 2000

| Variable | 1990 Odds ratio (lower–upper) | 2000 Odds ratio (lower–upper) | 2000 White women only including primary care doctors’ offices odds ratio (lower–upper) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atlanta | 1.028 (0.844–1.252) | 1.026 (0.864–1.219) | 0.840 (0.677–1.043) |

| Detroit | 1.116 (0.953–1.305) | 0.995 (0.857–1.156) | 0.932 (0.786–1.106) |

| Age | 1.012*** (1.007–1.017) | 1.009*** (1.005–1.014) | 1.012*** (1.006–1.018) |

| Unmarried | 1.413*** (1.229–1.626) | 1.63*** (1.431–1.858) | 1.57*** (1.337–1.846) |

| NH black | 1.334** (1.081–1.647) | 1.53*** (1.28–1.827) | NA |

| NH Asian PI | 1.524* (1.066–2.179) | 1.243 (0.95–1.625) | NA |

| Hispanic | 1.371 (0.93–2.022) | 1.255 (0.908–1.735) | NA |

| MUA | 1.196 (0.955–1.497) | 1.027 (0.856–1.232) | 1.007 (0.736–1.329) |

| Poverty 20–39% | 1.428*** (1.138–1.793) | 1.396*** (1.123–1.736) | 1.909*** (1.337–2.726) |

| Poverty 40%+ | 1.7*** (1.242–2.328) | 1.802*** (1.206–2.693) | 5.107*** (2.117–12.321) |

| Number of primary care doctor’s offices | NA | 0.996 (0.992–1.001) | 0.994* (0.989–1.000) |

Reference groups: cities San Francisco, marital status married, race/ethnicity non-Hispanic white, MUA non-MUA, poverty = poverty <20%

95% CI for odds ratio

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Race/ethnicity, being unmarried and increasing age was significant explanatory factors in both 1990 and 2000. In 1990, non-Hispanic black women had 33% greater odds of being diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer relative to non-Hispanic white women, and the odds were 53% by 2000. Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander women had 52% greater odds than non-Hispanic white women of a late-stage diagnosis in 1990, but they were not at significantly greater risk in 2000.

We reestimated the three-city model for 2000 to include a measure of the number of primary care doctor’s office in each census tract under study. This variable was only significant in the three-city model for white women. The OR for white women is shown in Table 2 and, because the doctor’s office variable is continuous, we calculated its marginal effect. The proportion of non-Hispanic white women with late-stage diagnosis equaled 0.057. Taking the regression coefficient on the doctor’s office variable (−0.0056) and using the formula for a partial derivative (−0.0056 × 0.057 × 0.942) we found that an increase of one doctor’s office lowered the probability of a late-stage diagnosis by 0.03% at the mean probability. It is instructive to note the difference in proximity to a primary care doctor by racial/ethnic group. The mean number of doctors’ offices in a census tract for whites equaled 7.03 (standard deviation = 18.79), for blacks 3.18 (standard deviation = 10.83), for Hispanics 5.94 (standard deviation = 18.78), and for Asian/Pacific Islanders 5.45 (standard deviation = 14.96).

Table 3 shows the odds ratio estimations for each city in 1990 and 2000. Increased age and being unmarried increases the likelihood of a late-stage diagnosis and these findings were consistent across models. The significance of estimates for race/ethnicity and the importance of residential poverty levels by cities varied in 1990 and 2000. In 1990 and 2000, only women living in moderately poor neighborhoods of San Francisco faced elevated odds of a late-stage diagnoses. None of the poverty measures were significant in Atlanta in 1990 but, in 2000, women living in MUAs had higher odds of a late-stage outcome.

Table 3.

Likelihood of a late-stage breast cancer diagnosis by city: 1990 and 2000

| Variable | San Francisco | Detroit | Atlanta | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 Odds ratio (lower–upper) | 2000 Odds ratio (lower–upper) | 2000 Including doctors’ offices odds ratio (lower–upper) | 1990 Odds ratio (lower–upper) | 2000 Odds ratio (lower–upper) | 2000 Including doctors’ offices odds ratio (lower–upper) | 1990 Odds ratio (lower–upper) | 2000 Odds ratio (lower–upper) | 2000 Including doctors’ offices odds ratio (lower–upper) | |

| Sample size | 4,862 | 6,704 | 6,704 | 5,232 | 6,942 | 6,942 | 2,301 | 3,936 | 3,936 |

| Late stage no. | 365 | 407 | 407 | 449 | 452 | 452 | 171 | 254 | 254 |

| Age | 1.009* (1.002–1.017) | 1.003 (0.995–1.010) | 1.003 (0.995–1.010) | 1.013*** (1.006–1.021) | 1.02*** (1.012–1.027) | 1.02*** (1.013–1.027) | 1.014* (1.002–1.025) | 1.002 (0.993–1.012) | 1.002 (0.993–1.012) |

| Unmarried | 1.190 (0.949–1.492) | 1.609*** (1.304–1.986) | 1.609*** (1.303–1.986) | 1.562*** (1.267–1.925) | 1.676*** (1.358–2.069) | 1.686*** (1.366–2.081) | 1.55* (1.101–2.182) | 1.494* (1.131–1.974) | 1.505** (1.139–1.988) |

| NH black | 1.249 (0.850–1.834) | 1.198 (0.827–1.734) | 1.199 (0.828–1.737) | 1.098 (0.798–1.511) | 1.434** (1.074–1.915) | 1.410* (1.055–1.884) | 2.153*** (1.42–3.264) | 2.018*** (1.481–2.748) | 1.97*** (1.444–2.687) |

| NH Asian PI | 1.495* (1.032–2.166) | 1.040 (0.769–1.406) | 1.041 (0.769–1.407) | 0.915 (0.118–7.075) | 2.356* (1.058–5.243) | 2.418* (1.085–5.386) | 0.9 (0.118–6.863) | 2.283 (0.958–5.445) | 2.294 (0.961–5.474) |

| Hispanic | 1.262 (0.822–1.937) | 1.124 (0.779–1.622) | 1.124 (0.779–1.623) | 1.829 (0.604–5.537) | 1.398 (0.417–4.685) | 1.367 (0.408–4.586) | NA | 1.600 (0.682–3.755) | 1.615 (0.688–3.793) |

| MUA | 1.265 (0.878–1.822) | 0.876 (0.640–1.199) | 0.877 (0.640–1.201) | 1.239 (0.879–1.747) | 1 (0.729–1.373) | 0.992 (0.723–1.361) | 1.034 (0.586–1.825) | 1.406* (1.013–1.950) | 1.379 (0.993–1.915) |

| Poverty 20–39% | 1.593* (1.069–2.375) | 1.661* (1.091–2.528) | 1.661* (1.091–2.528) | 1.409* (1.012–1.96) | 1.466* (1.06–2.028) | 1.433* (1.036–1.982) | 1.231 (0.733–2.069) | 1.224 (0.783–1.915) | 1.222 (0.782–1.909) |

| Poverty 40%+ | 1.766 (0.568–5.490) | 1.107 (0.254–4.819) | 1.105 (0.254–4.812) | 1.927*** (1.309–2.837) | 1.794 (0.985–3.268) | 1.728 (0.948–3.150) | 1.003 (0.418–2.404) | 1.717 (0.926–3.182) | 1.735 (0.935–3.22) |

| Number of doctors’ offices | NA | NA | 1.000 (0.995–1.006) | NA | NA | 0.985* (0.971–0.999) | NA | NA | 0.995 (0.987–1.003) |

95% CI for odds ratios: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

1989–1990 Data on Hispanics and Asians in Atlanta were combined due to insufficient numbers

In 1990, women living in high-poverty areas in Detroit had 93% greater odds of receiving a late-stage diagnosis than women in low-poverty neighborhoods. In 2000, residence in high poverty was only weakly significant (p = 0.056), perhaps due to the small number of late-stage cases who resided in high-poverty census tracts (17 cases). However, in 1990 and 2000, residents of moderately poor areas had 41% and 47% greater odds, respectively, of receiving a late-stage diagnosis than did women who resided in low-poverty areas. In 1990, race/ethnicity had not been a significant determinant of late-stage odds in Detroit but by 2000, the odds of black women receiving a late-stage diagnosis increased to 43% and the odds for Asian/Pacific Islander women increased to 136% more likely than the odds for white women. In Detroit, an increase of one doctor’s office decreased odds of a late-stage diagnosis by 0.09% at the mean probability. Table 1 reveals that relative to the other two cities, Detroit registered the smallest mean number of doctors found within a census tract.

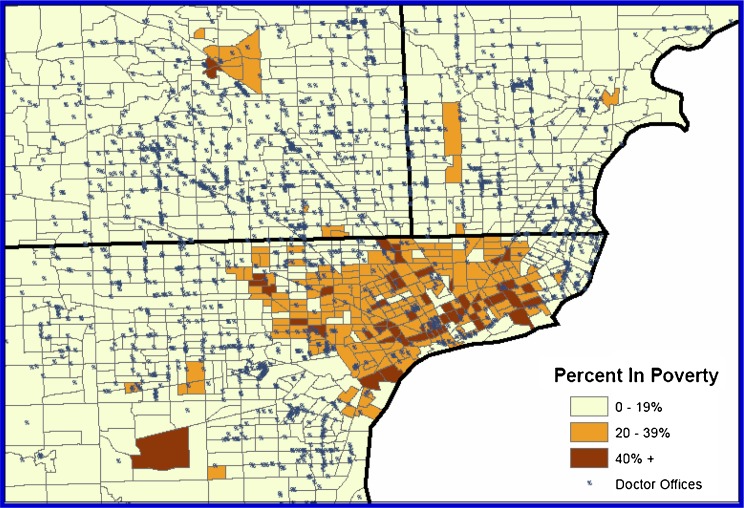

The map of Detroit shown in Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of primary care doctor’s offices among the three levels of poverty in the Detroit SEER area in 2000. In Detroit, 75% of high-poverty tracts, 65% of moderate-poverty tracts and 34% of low-poverty tracts had no primary care doctors’ offices at all.

FIGURE 2.

Location of primary care doctor’s offices in Detroit, Detroit SEER Registry, 2000.

Discussion

Late-stage breast cancer rates declined from 8% to 6% in the three-city model between 1990 and 2000. We tested whether late-stage rates continued to be associated with increasing poverty levels in 2000 as they were in 1990. Even though the percentage of all cases residing in high-poverty areas declined from 4% in 1990 to 1% in 2000, the odds of a late-stage diagnosis for women living in these areas remained high. Unwin, in a discussion of the limitations of economic growth as a solution to “extreme poverty,” argued that relative poverty is a better measure than absolute poverty because “the greatest poverty is found where there are the greatest differences in income levels, or access to resources.”33(p. 937) Social processes of exclusion give rise to health inequalities and we see that in the findings on our residential poverty measures.

The economic geography of uneven development within urban areas over the last 40 years reveals an increased spatial segregation and economic isolation of the urban poor.34 Using a simple poverty measure that distinguished areas within our three cities by level of poverty, we found that greater relative poverty is the persistent context for late-stage diagnosis. Our results are concordant with MacKinnon et al.,35 who found residing in high-poverty areas in Florida was significantly associated with late-stage diagnosis of breast cancer. However, they did not find urbanization at the county level had much of an effect on the late-stage incidence and poverty gradient.

Odds ratios from the regressions for specific cities affirm that combining data across cities may not reveal existing disparities across residential poverty levels and racial/ethnic groups. Findings show residents of moderately poor areas in San Francisco and Detroit had heightened odds of a late-stage diagnosis when compared to women living in low-poverty neighborhoods in both 1990 and 2000. Yet, in Atlanta, residential poverty was not associated with late stage. Asian and Pacific Islanders in San Francisco had higher odds of late-stage disease in 1990 relative to whites, but by 2000, race or ethnicity was not significant. In Atlanta, both in 1990 and 2000, black women were more likely to receive a late-stage diagnosis when compared to whites. In Detroit, the odds faced by black women and Asian and Pacific Islanders were significantly higher than those facing whites in 2000, but race and ethnicity were not significant in 1990. Mobley et al.20 found similar heterogeneity when estimates from pooling samples from many states were compared with those taken at the individual state level. The pooled estimates gave misleading information on the use of mammography services and on race and place effects in black–white utilization rates.

Our finding on higher odds facing black women in 2000 in Detroit is supported by Dai’s36 study. She established that populations with low socioeconomic status who lived in areas with greater black segregation and limited access to mammography experienced higher rates of late diagnosis.36 Although her study did not include an individual-level race variable, her findings did show the negative impact on diagnostic stage of living in areas with higher levels of black segregation, economic disadvantage, and limited access to healthcare. Schulz et al.37 also found that the residential segregation of African Americans in Detroit negatively impacted their ability to access healthcare resources. However, our findings that Asian/Pacific Islanders living in Detroit are at greater risk of a late-stage diagnosis is not well documented and requires further research.

The elevated likelihood of a late-stage diagnosis for women residing in increasing poverty areas may signal inconveniently located screening services, high costs of mammography, inadequacies in insurance coverage, or incomplete information on breast cancer prevention and follow-up treatment among residents, just to name a few possibilities. A study of Chicago mammography facilities by Tarlov et al.38 revealed that homicide rates in facility locations were associated with late-stage breast cancer diagnosis. This study shows how including relevant neighborhood characteristics in a regression analysis can improve our understanding of how access to healthcare resources is impeded.

We found an increase in the number of neighborhood primary care doctors’ offices was associated with decreased odds of late-stage diagnosis for Detroit women and for white women in the three-city model. Otherwise, this factor was not significant in our tests. Greater variation in access to primary care doctors in the residential location of white women might help explain these findings. Given the extreme racial segregation characterizing Detroit and the general lack of physician offices in the areas where blacks are concentrated, the significance of primary care doctors’ offices for women in this city may be driven by the residential distribution of white women. While there is variation among white women in their access to primary care doctors, there is little variation among black women. As noted above, 75% of high-poverty census tracts, where black residents are concentrated, have no doctors’ offices.

Metro Detroit is “highly stratified along racial and ethnic lines, with blacks largely confined to the central city and its close-in suburbs to the north” and “the ability to access goods and services in Detroit is defined by this racial–ethnic stratification”.39 As we saw in Figure 2, access to primary care physicians is inadequate in the central city. And it is largely non-Hispanic blacks who are affected by the absence of primary care resources here. Urban areas characterized by higher poverty levels have a lower population density relative to low-poverty areas. Physicians set up practices where they can establish optimal caseloads to cover practice costs.40 This helps explain why there are fewer primary care practices in poorer neighborhoods.

The patterns of unequal distribution of primary care physicians we observed in Detroit and associated implications for population health have been noted in other studies. Prinz and Soffel’s study of low-income neighborhoods in New York City41 found that the number of physicians in private practice was small, causing low-income communities to be heavily dependent on hospital outpatient departments, community health centers, and hospital satellite clinics. And physicians are significantly less likely to be Medicaid participants in areas that are racially segregated or where the poor are nonwhite,42 thereby attenuating access problems. Despite the limited significance of primary care doctor’s offices in our overall results, researchers need to exploit existing data to better quantify the association between the supply of generalists and breast cancer stage at detection.

Conclusions

Policy interventions are effective only when they are tailored to the specific communities and places that need them. Free and low-cost cancer screening programs are important in improving early detection of breast cancer in poor urban communities.43 One solution to increasing screening rates and decreasing late-stage diagnoses would be to provide access to organized screening programs to all women 50 and older. Organized programs are in force in other developed countries and have shown promise in the USA,44 but are not widely used.12,45 Disparities in access to primary care doctors could be managed if expansion of the primary care physician workforce is coupled with support or financial incentives to encourage the location of practices in underserved urban areas.46 Interventions should target impoverished urban areas for receipt of breast cancer screening resources. In Detroit, this would mean direct investment to increase the number of primary care physicians located in poorer neighborhoods.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Emily Boling for data retrieval from ICIC files and Penny Randall-Levy for expert reference management.

Footnotes

Shape files for primary care doctor’s offices in San Francisco, Detroit, and Atlanta census tracts were generated from Dunn and Bradstreet data and provided to the researchers by programmers at ICIC. More information on ICIC is available at http://www.icic.org/research-and-analysis/research-definitions.

Contributor Information

Janis Barry, Phone: +1-212-6366077, Email: barryfiguero@fordham.edu.

Nancy Breen, Email: Breenn@mail.nih.gov.

Michael Barrett, Email: BarrettM@imsweb.com.

References

- 1.Barry J, Breen N. The importance of place of residence in predicting late-stage diagnosis of breast or cervical cancer. Health Place. 2005;11:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Figueroa JB, Breen N. Significance of underclass residence on the stage of breast or cervical cancer diagnosis. Am Econ Rev. 1995;85:112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jargowsky PA. Stunning progress, hidden problems: the dramatic decline of concentrated poverty in the 1990s. living cities census series. Washington: The Brookings Institution, Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crandall MS, Weber BA. Local social and economic conditions, spatial concentrations of poverty, and poverty dynamics. Am J Agric Econ. 2004;86:1276–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.0002-9092.2004.00677.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massey DS, Fischer MJ. The geography of inequality in the United States, 1950–2000. In: Gale WJ, Pack JR, editors. Brookings–Wharton papers on urban affairs. Washington: Brookings Institution Press; 2003. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Do DP, Finch BK. The link between neighborhood poverty and health: context or composition? Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:611–619. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gumpertz ML, Pickle LW, Miller BA, Bell BS. Geographic patterns of advanced breast cancer in Los Angeles: associations with biological and sociodemographic factors (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:325–339. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sands G, Reese LA. Current practices and policy recommendations concerning Public Act 198 industrial facilities tax abatements. East Lansing: Land Policy Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grengs, J. Space and change in the measurement of poverty concentration: Detroit in the 1990s. National Poverty Center Working Paper Series #06–39. Ann Arbor, MI: National Poverty Center; 2006.

- 10.Swanstrom T, Ryan R, Stigers KM. Measuring concentrated poverty: the federal standard vs. a relative standard. Hous Policy Debate. 2008;19:295–321. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2008.9521637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Preventive Services Task Force. US Preventive Services Task Force: screening for breast cancer. December, 2009. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/USpstf/uspsbrca.htm. Accessed January 21, 2010.

- 12.Taplin SH, Ichikawa L, Buist DS, Seger D, White E. Evaluating organized breast cancer screening implementation: the prevention of late-stage disease? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:225–234. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-03-0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burack RC, Gimotty PA, Stengle W, Warbasse L, Moncrease A. Patterns of use of mammography among inner-city Detroit women: contrasts between a health department, HMO, and private hospital. Med Care. 1993;31:322–334. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breen N, Wagener DK, Brown ML, Davis WW, Ballard-Barbash R. Progress in cancer screening over a decade: results of cancer screening from the 1987, 1992, and 1998 National Health Interview Surveys. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1704–1713. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.22.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meissner HI, Breen N, Taubman ML, Vernon SW, Graubard BI. Which women aren’t getting mammograms and why? (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2003;97:1528–1540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sassi F, Luft HS, Guadagnoli E. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in female breast cancer: screening rates and stage at diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2165–2172. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leatherman S, McCarthy D. Quality of health care for medicare beneficiaries: a chartbook. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheehan TJ, DeChello LM. A space-time analysis of the proportion of late stage breast cancer in Massachusetts, 1988 to 1997. Int J Health Geogr. 2005;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mobley LR, Kuo TM, Driscoll D, Clayton L, Anselin L. Heterogeneity in mammography use across the nation: separating evidence of disparities from the disproportionate effects of geography. Int J Health Geogr. 2008;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schootman M, Jeff DB, Gillanders WE, Yan Y, Jenkins B, Aft R. Geographic clustering of adequate diagnostic follow-up after abnormal screening results for breast cancer among low-income women in Missouri. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:704–712. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breen N, Yabroff KR, Meissner HI. What proportion of breast cancers are detected by mammography in the United States? Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31:220–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karliner LS, Kerlikowske K. Ethnic disparities in breast cancer. Womens Health. 2007;3:679–688. doi: 10.2217/17455057.3.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Reschke AH, Aft RL. Disparities related to socioeconomic status and access to medical care remain in the United States among women who never had a mammogram. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:419–425. doi: 10.1023/A:1024941626748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrante JM, Gonzalez EC, Pal N, Roetzheim RG. Effects of physician supply on early detection of breast cancer. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000;13:408–414. doi: 10.3122/15572625-13-6-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrett RE, Cho YI, Weaver KE, et al. Neighborhood change and distant metastasis at diagnosis of breast cancer. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zenk SN, Tarlov E, Sun J. Spatial equity in facilities providing low- or no-fee screening mammography in Chicago neighborhoods. J Urban Health. 2006;83:195–210. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seiffert JE. SEER program: comparative staging guide for cancer. Version 1.1 (publication no. 93–3640) Bethesda: National Institutes of Health; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishaw A. Areas with concentrated poverty: 1999. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.ICIC Initiative for a Competitive Inner City. ICIC’s State of the inner city economies database. 2004. http://www.icic.org/site/c.fnJNKPNhFiG/b.5345879/k.6AA2/Inner_City_Economies/apps/lk/content2.aspx. Accessed March 23, 2009.

- 31.DeMaris A. Regression with social data: modeling continuous and limited response variables. New York: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grann V, Troxel AB, Zojwalla N, Hershman D, Glied SA, Jacobson JS. Regional and racial disparities in breast cancer-specific mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unwin T. No end to poverty. J Dev Stud. 2007;43:929–953. doi: 10.1080/00220380701384596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasmeier AK, Farrigan TL. Landscapes of inequality: spatial segregation, economic isolation, and contingent residential locations. Econ Geogr. 2007;83:221–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2007.tb00352.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKinnon JA, Duncan RC, Huang Y, et al. Detecting an association between socioeconomic status and late stage breast cancer using spatial analysis and area-based measures. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2007; 16: 756–762. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Dai D. Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place. 2010;16:1038–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulz AJ, Williams DR, Israel BA, Lempert LB. Racial and spatial relations as fundamental determinants of health in Detroit. Milbank Q. 2002;80:677–707. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarlov E, Zenk SN, Campbell RT, Warnecke RB, Block R. Characteristics of mammography facility locations and stage of breast cancer at diagnosis in Chicago. J Urban Health. 2009;86:196–213. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9320-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Detroit in focus: a profile from census 2000. Washington: The Brookings Institution; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenthal MB, Zaslavsky A, Newhouse JP. The geographic distribution of physicians revisited. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:1931–1952. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prinz TS, Soffel D. The primary care delivery system in New York’s low-income communities: private physicians and institutional providers in nine neighborhoods. J Urban Health. 2003;80:635–649. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greene J, Blustein J, Weitzman BC. Race, segregation, and physicians’ participation in Medicaid. Milbank Q. 2006;84:239–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oluwole SF, Ali AO, Adu A, et al. Impact of a cancer screening program on breast cancer stage at diagnosis in a medically underserved urban community. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:180–188. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01765-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adams EK, Florence CS, Thorpe KE, Becker ER, Joski PJ. Preventive care: female cancer screening, 1996–2000. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:301–307. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tangka F, Chattopadhyay S, Dalaker J, Gardner J, Royalty J, Hall IJ, DeGroff A, Alshafie G, Blackman D. Estimates of women screened through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holmes G. Does the National Health Service Corps improve physician supply in underserved locations? East Econ J. 2004;30:563–581. [Google Scholar]