Abstract

Over the decades, arthroscopy has grown in popularity for the treatment of many foot and ankle pathologies. While anterior ankle arthroscopy is a widely accepted technique, posterior ankle/subtalar arthroscopy is still a relatively new procedure. The goal of this review is to outline the indications, surgical techniques, and results of posterior ankle/subtalar arthroscopy. The main indications include: 1) osteochondral lesions (of subtalar and posterior ankle joint); 2) posterior soft tissue or bony impingement; 3) os trigonum syndrome; 4) posterior loose bodies; 5) flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tenosynovitis; 6) posterior synovitis; 7) subtalar (or ankle) joint arthritis; 8) posterior tibial, talar, or calcaneal fractures (for arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation). Although posterior ankle/subtalar arthroscopy has shown to be safe and effective in the treatment of many of the above mentioned conditions, thorough knowledge of the anatomy, correct indications, and a precise surgical technique are essential to produce good outcomes.

Keywords: Posterior ankle arthroscopy, Subtalar arthroscopy, Prone arthroscopy, Osteochondral lesions, Os trigonum, Posterior arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis, Talocalcaneal coalitions, Foot and ankle

Introduction

Over the decades, arthroscopy of the ankle has grown and improved considerably. In 1931, Burman was the first to attempt an ankle arthroscopy [1]. He became convinced of the impossibility of such a procedure because of the limited space and close relationship of the delicate anatomical structures. Forty years later, in 1972, thanks to technological advances, Watanabe was the first to report on a series of 28 ankle arthroscopies [2]. Since then, numerous studies and substantial progress have been made, and arthroscopic ankle surgery has gradually changed from a purely diagnostic means to a therapeutic tool.

Historically, the hindfoot was approached with a three-portal technique (anteromedial, anterolateral, and posterolateral) and the patient supine [3]. However, with anterior arthroscopy it is difficult to approach the posterior aspect of the ankle joint, and the subtalar joint is not visualized. For these reasons, a new two-portal posterior approach was introduced for hindfoot arthroscopy with the patient in the prone position [4]. This new approach provides excellent access to the posterior compartment of the ankle as well as extra-articular posterior structures, and therefore, the posterior ankle arthroscopy has grown in popularity. The widespread use of arthroscopy of the ankle is also attributable to its advantages compared with open surgery: direct visualization of the structures, less post-operative morbidity, faster rehabilitation, earlier resumption of sports, and outpatient treatment [5•, 6, 7].

Nowadays, posterior ankle arthroscopy represents a safe and reliable treatment option for different pathologies of the ankle and hindfoot. The aim of this review is to outline the most common indications for posterior ankle/subtalar arthroscopy as well as describe the surgical techniques and the results.

Indications and contraindications

The indications for posterior arthroscopy include both intra- and extra-articular pathologies and may involve: 1) bone (hypertrophic posterior talar process, os trigonum, bipartite talus, loose bodies, ossicles, post-traumatic ossifications, avulsion fragments, posterior facet talocalcaneal coalition, Haglund’s deformity, osteophytes, posterior tibial, talar or calcaneal fractures, Cedell fracture); 2) cartilage (posterior talar, tibial, or calcaneal osteochondral defects, arthritis, chondromatosis, talar cystic lesions, intraosseous talar ganglia); or 3) soft tissues (flexor hallucis longus tendinopathy, symptomatic inflammation of the retrocalcaneal bursa, post-traumatic synovitis, villonodular synovitis, and soft-tissue impingement) [4, 5•, 8–19]. Most of these conditions (excluding fractures) should initially be treated conservatively with: rest, ice, physical therapy, orthosis, analgesics or anti-inflammatory drugs, and local injections. If these measures fail, surgical treatment should be considered [8].

Some authors proposed the use of arthroscopy for the treatment of ankle fractures. However, definitive indications for arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation have not been established yet. This is a valid approach for two-fragment fractures without significant soft-tissue damage, but more complex fractures are difficult to treat arthroscopically, and open surgery is usually required [9•]. In addition, it has to be mentioned that arthroscopy is a valuable diagnostic and prognostic tool, which allows identifying intra-articular damages that would otherwise remain unrecognized.

Prone ankle arthroscopy is contraindicated in cases of inadequate conservative treatment, localized soft tissue infection, previous open surgery (with extensive scar around the posteromedial neurovascular bundle or FHL tendon) and severe soft-tissue damage associated with trauma. Caution must be taken with the presence of vascular diseases (including diabetic vascular disease and the absence of posterior tibial pulses), severe edema, and moderate degenerative joint disease. [5•, 9•, 10•, 17•, 20]

Physical examination and preoperative work-up

Physical examination starts with a thorough investigation into the patient’s history. Previous injuries or surgeries to the foot and ankle, together with the type of pain, its duration, and location, should be carefully evaluated. The activities eliciting the pain and any previous conservative treatments should also be investigated.

Abnormal gait or alignment should be evaluated. Then, accurate inspection and palpation of the foot and ankle are carried out. All articular and periarticular structures, such as muscles, bones, ligaments, tendons, blood vessels, and nerves must be carefully evaluated. Any organic or functional abnormalities should be considered. The tibialis posterior, FHL, and peroneal tendons should be palpated at rest and against resistance in order to reproduce the symptoms.

Pain with hyperplantarflexion is typical of posterior ankle impingement. The symptoms are usually elicited with running or walking on uneven surfaces. Sometimes, tenderness can be appreciated at the posterolateral or posteromedial ankle [21, 22]. An injection with local anesthetic may help clarify an uncertain diagnosis [5•].

Typical symptoms of osteochondral lesions or loose bodies include pain, catching, snapping, grinding, swelling, and tenderness around the involved joint [8]. Sometimes, impaired function, limited range of motion, stiffness, and locking may be present [23•]. Burning, electrical sensations, and tingling over the base of the foot and the heel need to be ruled out because these symptoms are suggestive for peripheral nerve compression syndromes [8].

The pre-operative work-up includes weight-bearing radiographs of both ankles in anteroposterior, lateral, and mortise views together with an oblique view of the foot [8]. The oblique view with the foot in 25 degrees external rotation is useful to differentiate between hypertrophy of the posterior talar process or os trigonum [5•]. When malalignment of the hindfoot is present, a Cobey/Saltzman view is required [8]. When necessary, an MRI or CT scan can be obtained for further evaluation of soft tissues and bone, respectively.

Surgical technique

Posterior ankle/subtalar arthroscopy is performed with the patient prone, under general or spinal anesthesia. Preoperative intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis is performed (usually with Cefazolin 2 g). Adequate padding is positioned to protect the ventral areas of the patient such as the genitals, abdomen, knees, elbows, and breasts from excessive pressure. The ankle is left hanging off the operating table so that it can be moved freely during surgery. A tourniquet is placed at the proximal thigh and inflated to 300 mmHg. Distraction is not routinely applied.

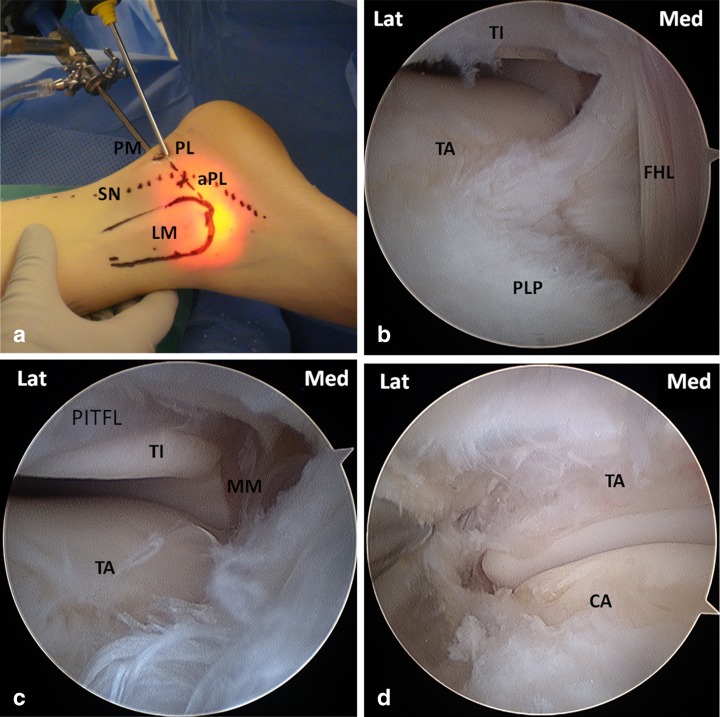

A surgical pen is used to mark the Achilles tendon and the lateral malleolus. With the foot in neutral position (90°), a straight line parallel to the foot sole is drawn from the tip of the lateral malleolus to the Achilles tendon. The posterolateral portal (PL) is made just proximal to this line and tangential to the Achilles tendon. The posteromedial (PM) portal is located at the same level on the medial side of the Achilles tendon (Fig. 1a). Ten ml of saline are injected into the ankle or subtalar joint with a syringe. Then, the vertical skin incision of the PL portal is made. Dissection of the subcutaneous tissue and deeper layers is performed bluntly with a mosquito clamp, which is oriented towards the first interdigital space. A 2.7 or 4.0-mm arthroscope is then inserted into the joint. The posterior talar process can be palpated and used as a landmark between ankle and subtalar joints. The PM portal skin incision is then made at the same level and parallel with respect to the PL portal. Deep dissection is performed with a mosquito clamp as previously described. The clamp is directed toward the arthroscope shaft at a 90° angle, then it is moved along the shaft and opened in front of the tip of the arthroscope in order to create space and improve visualization. A 2.9 full-radius mm shaver is then inserted into the PM portal, and initial synovectomy is performed. The FHL tendon is an important landmark and should always be identified, debrided from its sheath, and kept in view medially in order to avoid damage to the neurovascular bundle during the whole procedure. Passive motion of the great toe will assist in the identification of the FHL (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Lateral aspect of the ankle showing portal placement. PM = PosteroMedial portal; PL = PosteroLateral portal; aPL = Accessory PosteroLateral portal; LM = Lateral Malleolus; SN = Sural Nerve. b Identification of the FHL sheath (view from PL portal). TI = Tibia; TA = Talus; FHL = Flexor Hallucis Longus; PLP = PosteroLateral Process of the talus. c Ankle joint (view from PL portal). TI = Tibia; TA = Talus; MM = Medial Malleolus; PITFL = Posterior Inferior Tibio Fibular Ligament. d Subtalar joint (view from PL portal). TA = Talus; CA = Calcaneus

Both ankle and subtalar joints can be approached (Fig. 1c,d). From lateral to medial the following structures can be identified: lateral malleolus, posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (PITFL), posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), FHL, posterolateral process (PLP) of the talus, posterior tibiotalar ligament (PTTL, part of the deep deltoid), and medial malleolus. When examining the tibiotalar joint, the arthroscope is advanced between the PITFL and the PTFL, gently elevating the PITFL with the probe. The subtalar joint is clearly visible below the PTFL. When examining the subtalar joint, a probe can be inserted between the talus and calcaneus to palpate the articular cartilage. Gentle levering of the probe can distract the joint and improve visualization. A noninvasive distraction strap is usually ineffective in improving subtalar joint visualization. If subtalar joint opening is required, a transcalcaneal thin wire distraction is recommended [24•].

A wide variety of different conditions can be treated according to the preferred surgical technique through this two-portal posterior approach. These include: 1) osteochondral lesions (of subtalar and posterior ankle joint); 2) posterior soft tissue or bony impingement; 3) os trigonum syndrome; 4) posterior loose bodies; 5) flexor hallucis longus (FHL) or peroneal tenosynovitis; 6) posterior synovitis; 7) subtalar (or ankle) joint arthritis; 8) posterior tibial, talar, or calcaneal fractures (for arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation or loose body removal).

In case of FHL tendonitis, posterior impingement, or os trigonum syndrome, the FHL is debrided from its sheath and adhesions. When an os trigonum is present, this is debrided circumferentially of all the attached soft tissues. The synchondrosis between the talus and os trigonum is palpated with a freer elevator and cracked by levering maneuvers. The os trigonum is removed as a whole, preferably, or piecemeal, using a grasper. In the presence of an intact enlarged trigonal process, this is removed entirely with a burr. The posterior aspect of the talus is evaluated and any sharp bony edges are smoothed out. The most posterior aspect of the articular cartilage of the posterior talar facet of the subtalar joint is always removed together with the os trigonum.

After posterior impingement syndrome, FHL release, os trigonum removal, or OCL debridement, the patient can be discharged the same day of surgery and weight-bearing is allowed as tolerated. The patient is instructed to elevate the foot when not walking to prevent edema. The dressing is removed three days postoperatively. Performing active range of motion exercises for at least 3 times a day for 10 min each is encouraged [5•].

When performing an arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis, an accessory PL portal can be established approximately 1 cm proximal and 1 cm posterior to the tip of the lateral malleolus just posterior to the peroneal sheath and anterior to the sural nerve (Fig. 1a). Blunt dissection on the posterior aspect of the peroneal sheath and careful instrument insertion is required since the sural nerve can be in direct contact. This additional portal can be used to distract the joint by inserting a large blunt trocar. Most of the procedure can be completed with the arthroscope in the PL portal and the instruments posteromedial, although both portals can be used in an alternating fashion for viewing and for instrumentation. The articular cartilage of the entire posterior facet is removed with a 4 mm burr, a shaver, and multi-angled curettes. Overall, 1 to 2 mm of subchondral bone is removed until cancellous bone is visible. Care is taken not to alter the geometry of the joint. All the debridement is done posterior to the interosseous ligament, which must be visualized. Morcellized cancellous allograft is inserted through a small arthroscopic sleeve. In this fashion, only the posterior facet is fused. Alternatively, the use of a third sinus tarsi portal has been described, in addition to standard PM and PL portals [13•]. Less commonly, a trans-Achilles portal can be used during prone arthroscopy. Fixation is achieved with 2 cannulated 6.5 mm partially threaded cancellous screws that are inserted under fluoroscopic control from the weight-bearing surface of the heel to the talus neck or body. Similarly, a sinus tarsi portal can be used to distract the joint and to remove the cartilage from the anterior articular surface of the subtalar joint, which is not accessible from the PM and PL portals.

After a posterior arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis, a below knee cast is applied and the patient is kept non-weight-bearing for 6 weeks. At 6 weeks, the cast is removed, while ROM exercises and gradual weight-bearing in a short leg removable boot are started. At 12 weeks, the patient can be progressed without limitations if callus formation is evident on the radiographs. Clinical and radiological evaluation is performed at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 10 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year after surgery.

Osteochondral lesions

Posterior osteochondral lesions (OCL) of the tibia and talus are better visualized with a posterior approach. This area is particularly difficult to visualize from the front. In general, an average of 54 % of the talar dome can be reached with a prone arthroscopy [20]. The indications and arthroscopic treatment of posterior OCL are comparable in both anterior and posterior arthroscopy and depend on the size and chronicity of the lesion, age of the patient, alignment, previous conservative and surgical treatments, and most of all, symptoms. With a posterior arthroscopic approach, all of the following techniques can be used for OCL treatment: debridement and abrasion arthroplasty, bone marrow stimulation, autologous cancellous grafting, anterograde/retrograde drilling, fixation, osteochondral transplantation, Autologous Matrix Induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC), and autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI). The outcomes of OCL treated with a posterior arthroscopic approach have not been reported yet, but we can assume they are comparable to those of anterior arthroscopy, ranging from 76 % to 89 % success rate according to the repair technique used [23•].

Posterior ankle impingement, os trigonum syndrome, and FHL tenosynovitis

The posterolateral process of the talus has a secondary ossification center that mineralizes between 7 and 13 years of age and in 7 % to 14 % of the population may also remain as a separated ossicle (also known as os trigonum). In a small percentage of cases it can be symptomatic [8]. Os trigonum syndrome usually presents as posterior, posteromedial, or posterolateral ankle joint pain, and FHL tenosynovitis is often associated. History, clinical examination, and a lateral view of the ankle are usually sufficient for the diagnosis. Non-operative treatment and long-term modification of activities is usually the first-line management, with a 60 % rate of symptoms improvement [8]. Conservative treatment includes rest, ice, anti-inflammatory medications, immobilization in a short-leg walking cast, avoidance of forced plantarflexion activities, and physical therapy (heel cord stretching and isometric strengthening).

Surgical treatment is indicated when an appropriate conservative treatment (at least 3 months long) fails. Either arthroscopic or open debridement has been described. Although excellent outcomes have been reported with both open and arthroscopic resection [4, 25, 26], arthroscopic technique is less invasive, providing precise diagnosis and treatment with an early return to the previous activity level [26]. A 68–84 % rate of good or excellent outcomes has been reported after posterior arthroscopy for posterior ankle impingement [26].

Posteromedial impingement

Posteromedial ankle impingement is an uncommon disease in which a severe injury involves the deep posterior fibers of the medial deltoid ligament [8]. The ankle usually shows deep soft tissue induration and localized tenderness; pain is evocable palpating the medial retromalleolar area while moving the ankle [27]. If the symptoms are refractory to conservative treatment (physical therapy, strengthening, and corticosteroid injection), posterior arthroscopy is indicated. A thorough debridement and synovectomy resolves the symptoms in the majority of cases [27].

Haglund’s deformity and achilles tendon pathologies

Haglund’s syndrome, disease, or deformity refers to a prominent posterosuperior calcaneal tuberosity, mostly on the lateral side, associated with retrocalcaneal bursitis and Achilles tendonitis [28–33]. After failure of nonoperative treatment, the goal of surgery is to avoid the impingement of the bursa between the Achilles tendon and the calcaneal prominence. The inflamed bursa is thus removed, and the superoposterior calcaneal prominence is resected [34–36].

Open surgery requires large exposure with a consequent high risk of wound and soft tissue problems. The endoscopic approach offers an excellent visualization and reduces the risk of wound dehiscence, painful scars, and nerve entrapment within the scar [37]. One of the risks of hindfoot endoscopy for the treatment of Haglund’s deformity is not removing enough bone from the calcaneal tuberosity. Arthroscopic calcaneoplasty reported 95 % of favorable outcomes. [37]

With a two-portal approach (one made approximately 10 to 12 cm proximal to the calcaneal tuberosity near the tendon-muscle junction and the other just above the tuberosity), the whole length of the achilles tendon can be inspected, and adhesions, inflammation, and scar tissue around the tendon can be treated [14].

Subtalar arthrodesis

Subtalar arthrodesis is indicated for symptomatic post-traumatic and inflammatory arthritis, posterior tibial tendon dysfunction, and congenital deformities when conservative treatments fail [8, 38–43]. Open techniques have generally reported favorable results, though nonunion rates can be as high as 5 % to 16 % [41, 42]. Arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis in prone position through a posterior two-portal approach was developed to improve the outcomes of open techniques. The advantages of the arthroscopic approach include: safe access, superior visualization of the posterior talocalcaneal facet, easy screw fixation, less post-operative pain, minimal invasiveness, and preservation of calcaneal/talar blood supply [8, 44•]. Fusion rates range from 91 % to 100 % with this technique [43, 45•, 46–49].

Talocalcaneal coalitions

Talocalcaneal coalitions (TCC) account for approximately 53 % of all tarsal coalitions and affect 1 to 6 % of the population [50]. Although asymptomatic in most cases, TCC can become symptomatic in young adults after a minor injury to the hindfoot. The first-line approach is conservative treatment, including: activity modification, orthoses, anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, and cast immobilization in case of severe pain [51].

After failure of conservative treatment, excision of symptomatic TCC may be indicated if less than 50 % of the subtalar joint is involved and there is an absence of degenerative changes to the subtalar or surrounding tarsal joints. When severe degenerative changes in the tarsal joints are present or more than 50 % of the subtalar joint is involved, subtalar or triple arthrodeses are indicated.

Because patients are usually young, an attempt is usually made to excise the coalition and preserve the joint motion without burning any bridges for subsequent fusion in case of TCC resection failure.

Favorable results have been reported in 80 % to 100 % of patients with open resection [10•], however this approach does not provide adequate visualization of the posterior facet and exposition of the posterior extension of the coalition. To overcome these drawbacks, posterior arthroscopic resection of symptomatic TCC has been described recently, but the outcomes of this procedure are still unavailable [10•].

Fractures

Reduction and internal fixation with assistance of posterior arthroscopy has been described for the treatment of non-complex posterior fractures of the tibia, talus and, calcaneus. Small fragments can be removed while larger fragments can be fixed acutely with one or more cannulated screws. Furthermore, arthroscopy offers the opportunity to assess and manage combined intra-articular damages associated with the fracture [9•].

Complications

In a multicenter study, Nickisch et al. reported the complication of posterior ankle and hindfoot arthroscopy [52•]. Out of 189 ankles, postoperative complications were observed in 16 patients (8.5 %) and included: plantar numbness (4 cases and 3 resolved), sural nerve dysesthesia (3 cases and 2 resolved), Achilles tendon tightness (4 cases and all resolved), and complex regional pain syndrome and infection (2 cases each and all resolved). The authors concluded that posterior ankle/hindfoot arthroscopy can be performed with a low incidence of major postoperative complications. To our best knowledge, this is the largest case series reporting about the complications of posterior ankle arthroscopy.

These findings are also supported by several anatomical studies [53–55] examining the PM and PL portals and their relationships with neighboring neurovascular structures. Although concerns have been expressed in the past about the risk of damaging the neurovascular structures while performing the PM portal [39, 48, 56–64], recently, it has been shown that posterior ankle/subtalar arthroscopy is safe and effective [4, 45•, 53, 65–69].

Conclusions

Arthroscopy/endoscopy has become an important mean in the treatment of numerous ankle, subtalar, and extra-articular pathologies, with the advantage of a quicker recovery and a shorter hospitalization compared with traditional open techniques. Despite the minimal invasiveness of the technique, anterior and posterior arthroscopy is not free from complications. Posterior ankle/subtalar arthroscopy has a longer learning curve compared with anterior arthroscopy and should be performed by skilled arthroscopists. A thorough knowledge of the anatomy, correct indications, and a precise surgical technique are essential to produce good outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

- 1.Burman MS. Arthroscopy of direct visualization of joints. An experimental cadaver study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1931;13:669–695. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200109000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe M. Selfoc-Arthroscope (Watanabe no. 24 Arthroscope) monograph. Tokyo: Teishin Hospital; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferkel RD, Heath DD, Guhl JF. Neurological complications of ankle arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:200–208. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(96)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dijk CN, Scholten PE, Krips R. A 2-portal endoscopic approach for diagnosis and treatment of posterior ankle pathology. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2000;16:871–876. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.19430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leeuw PAJ, Sterkenburg MN, Dijk CN. Arthroscopy and endoscopy of the ankle and hindfoot. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2009;17:175–184. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181a5ce78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scranton PE, Jr, McDermott JE. Anterior tibiotalar spurs: a comparison of open versus arthroscopic debridement. Foot Ankle. 1992;13:125–129. doi: 10.1177/107110079201300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutsuries AM, Saltrick KR, Wagner J, Catanzariti AR. Arthroscopic arthroplasty of the ankle joint. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1994;11:449–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonasia DE, Germano M, Marmotti A, Amendola A: Prone Arthroscopy for Posterior Ankle and Subtalar Joint Pathology. In: Arthroscopic Surgery. The Foot & Ankle. Richard D. Ferkel. Edited by Terry L. Whipple. New edition. In press.

- 9.Bonasia DE, Rossi R, Saltzman CL, Amendola A. The role of arthroscopy in the management of fractures about the ankle. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:226–235. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonasia DE, Phisitkul P, Saltzman CL, et al. Arthroscopic resection of talocalcaneal coalitions. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2011;27:430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lui TH. Flexor hallucis longus tendoscopy: a technical note. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17:107–110. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0623-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lui TH, et al. The arthroscopic management of frozen ankle. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2006;22:283–286. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beimers L, Leeuw PAJ, Dijk CN. A 3-portal approach for arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17:830–8348. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0795-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morag G, Maman E, Arbel R. Endoscopic treatment of hindfoot pathology. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2003;19:E13. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholten PE, Altena MC, Krips R, Dijk CN. Treatment of a large intraosseous talar ganglion by means of hindfoot endoscopy. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2003;19:96–100. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yilmaz C, Eskandari MM. Arthroscopic excision of the Talar Stieda’s process. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2006;22:225.e1–225.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dijk CN, Leeuw PAJ, Scholten PE. Hindfoot endoscopy for posterior ankle impingement. Surgical Technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:287–298. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keeling JJ, Guyton GP. Endoscopic flexor hallucis longus decompression: a cadaver study. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:810–814. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2006.0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dijk CN, Bergen CJA. Advancements in ankle arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:635–646. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200811000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phisitkul P, Junko JT, Femino JE, et al. Technique of prone ankle and subtalar arthroscopy. Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;6:30–37. doi: 10.1097/01.btf.0000235419.53662.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brodsky AE, Khalil MA. Talar compression syndrome. Foot Ankle. 1987;7:338–344. doi: 10.1177/107110078700700606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedrick MR, McBryde AM. Posterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:2–8. doi: 10.1177/107110079401500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zengerink M, Struijs PAA, Tol JL, Dijk CN. Treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:238–246. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0942-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beals TC, Junko JT, Amendola A, et al. Minimally invasive distraction technique for prone posterior ankle and subtalar arthroscopy. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31:316–319. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2010.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abramowitz Y, Wollstein R, Barzilav Y, et al. Outcome of resection of a symptomatic os trigonum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1051–1057. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B7.14438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scholten PE, Sierevelt IN, Dijk CN. Hindfoot endoscopy for posterior ankle impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2665–2672. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonasia DE, Amendola A. Ankle Injuries. In: Rossi R, Margheritini F, editors. Orthopaedic Sports Medicine: Principles and Practice. Springer; 2010. p. 465–484.

- 28.Dee R. Miscellaneous disorders of the foot and ankle. In: Principles of Orthopaedic Practice. Second edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 1997:1033–1034.

- 29.Heneghan MA, Pavlov H. The Haglund painful heel syndrome. Experimental investigation of cause and therapeutic implications. Clin Orthop. 1984;187:228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le TA, Joseph PM. Common exostectomies of the rearfoot. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1991;8:601–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myerson MS, McGarvey W. Disorders of the insertion of the Achilles tendon and Achilles tendinitis. An instructional course lecture. J Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80:1814–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossi F, et al. The Haglund syndrome (H.S.): Clinical and radiological features and sports medicine aspects. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1987;27:258–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sella EJ, Caminear DS, McLarney EA. Haglund’s syndrome. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1998;37:110–114. doi: 10.1016/S1067-2516(98)80089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Angermann P. Chronic retrocalcaneal bursitis treated by resection of the calcaneus. Foot Ankle. 1990;10:285–287. doi: 10.1177/107110079001000508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones DC, James SL. Partial calcaneal ostectomy for retrocalcaneal bursitis. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:72–73. doi: 10.1177/036354658401200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pauker M, Katz K, Yosipovitch Z. Calcaneal ostectomy for Haglund disease. J Foot Surg. 1992;31:588–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dijk CN, Dijk GE, Scholten PE, Kort NP. Endoscopic Calcaneoplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:185–189. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290021101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies MB, Rosenfeld PF, Stavrou P, Saxby TS. A comprehensive review of subtalar arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:295–297. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferkel RD, Fasulo GJ. Arthroscopic treatment of ankle injuries. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25:17–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flemister AS, Jr, Infante AF, Sanders RW, Walling AK. Subtalar arthrodesis for complications of intraarticular calcaneal fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:392–399. doi: 10.1177/107110070002100506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Easley ME, Trnka H, Schon L, Myerson MS. Isolated subtalar arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:613–624. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mann RA, Beaman DN, Horton GA. Isolated subtalar arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:511–519. doi: 10.1177/107110079801900802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scranton PE., Jr Comparison of open isolated subtalar arthrodesis with autogenous bone graft versus outpatient arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis using injectable bone morphogenic protein-enhanced graft. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:162–165. doi: 10.1177/107110079902000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee KB, Park CH, Seon JK, Kim SM. Arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis using a posterior 2-portal approach in the prone position. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2010;26:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amendola A, Lee KB, Saltzman CL, Suh JS. Technique and early experience with posterior arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:298–302. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carro LP, Golano P, Vega J. Arthroscopic subtalar arthrodesis: The posterior approach in the prone position. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:445.e1–445.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee KB, Saltzman CL, Suh JS, et al. A posterior 3-portal arthroscopic approach for isolated subtalar arthrodesis. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:1306–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tasto JP, et al. Subtalar arthroscopy. In: McGinty JB, et al., editors. Operative arthroscopy. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. pp. 944–952. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tasto JP, Frey C, Laimans P, et al. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Instr Course Lect. 2006;49:259–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stormont DM, Peterson HA. The relative incidence of tarsal coalition. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;181:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lemley F, Berlet G, Hill K, et al. Current concepts review: Tarsal coalition. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:1163–1169. doi: 10.1177/107110070602701229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.• Nickisch F, Barg A, Saltzman CL, et al. Postoperative complications in patients after posterior ankle and hindfoot arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. In press. This article reports on the complications of posterior hindfoot arthroscopy in the largest case series currently available in the literature.

- 53.Sitler DF, Amendola A, Bailey CS, et al. Posterior ankle arthroscopy: an anatomic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:763–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tryfonidis M, Whitfield CG, Charalambous CP, et al. Posterior ankle arthroscopy portal safety regarding proximity to the tibial and sural nerves. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:370–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phisitkul P, Tochigi Y, Saltzman CL, et al. Arthroscopic visualization of the posterior subtalar joint in the prone position: a cadaver study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:511–515. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feiwell LA, Frey C. Anatomic study of arthroscopic portal sites of the ankle. Foot Ankle. 1993;14:142–147. doi: 10.1177/107110079301400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferkel RD. Complications in ankle and foot arthroscopy. In: Ferkel RD, Whipple TL, editors. Arthroscopic surgery: the Foot and Ankle. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 291–304. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fitzgibbons TC. Arthroscopic ankle debridement and fusion: indications, techniques, and results. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Voto SJ, Ewing JW, Fleissner PR, Jr, et al. Ankle arthroscopy: neurovascular and arthroscopic anatomy of standard and trans-Achilles tendon portal placement. Arthroscopy. 1989;5:41–46. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(89)90089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferkel RD, Scranton PE. Current concepts review. Arthroscopy of the ankle and foot. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1233–1242. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199308000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parisien JS, Vangness T, Feldman R. Diagnostic and operative arthroscopy of the ankle. An experimental approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987:228–236. [PubMed]

- 62.Ferkel RD, Fischer SP. Progress in ankle arthroscopy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989:210–220. [PubMed]

- 63.Ferkel RD. Arthroscopy of the foot and ankle. In: Mann RA, Coughlin MJ, editors. Surgery of the foot and ankle. Ed 7, Vol 2. St Louis: Mosby; 1999. pp. 1257–1297. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Golano P, Vega J, Perez-Carro L, et al. Ankle anatomy for the arthroscopist. Part I: The portals. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:253–273. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dijk CN. Hindfoot endoscopy. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2001;8:365–371. doi: 10.1097/00132585-200108040-00007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dijk CN. Hindfoot endoscopy. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:391–414. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sora MC, Jilavu R, Grübl A, et al. The posteromedial neurovascular bundle of the ankle: an anatomic study using plastinated cross sections. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2008;24:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Allegra F, Maffulli N. Double posteromedial portals for posterior ankle arthroscopy in supine position. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2010;468:996–1001. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0973-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pena Gomez FA, Amendola A. The ankle. In: McGinty JB, editor. Operative arthroscopy. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar]