Abstract

Objective

To describe prostate cancer patients’ knowledge of and attitudes toward out-of-pocket expenses (OOPE) associated with prostate cancer treatment or the influence of OOPE on treatment choices.

Material and Methods

We undertook a qualitative research study in which we recruited patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. Patients answered a series of open-ended questions during a semi-structured interview and completed a questionnaire about the physician’s role in discussing OOPE, the burden of OOPE, the effect of OOPE on treatment decisions, and prior knowledge of OOPE.

Results

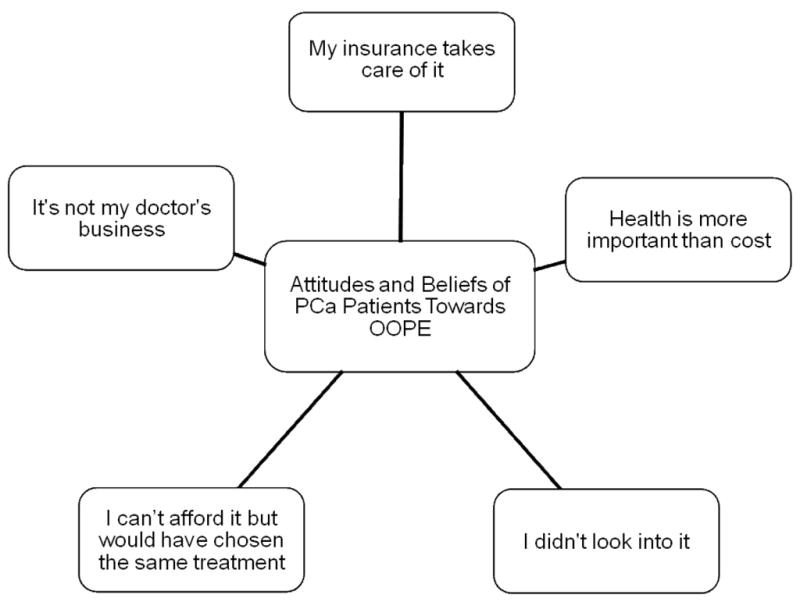

Forty-one (26 white, 15 black) eligible patients were enrolled from the urology and radiation oncology practices of the University of Pennsylvania. Qualitative assessment revealed five major themes: (1) “My insurance takes care of it” (2) “Health is more important than cost” (3) “I didn’t look into it” (4) “I can’t afford it but would have chosen the same treatment” (5) “It’s not my doctor’s business.” Most patients (38/41, 93%) reported that they would not have chosen a different treatment even if they had known the actual OOPE of their treatment. Patients who reported feeling burdened by out-of-pocket costs were socioeconomically heterogeneous and their treatment choices remained unaffected. Only two patients said they knew “a lot” about the likely out-of-pocket costs for different prostate cancer treatments before choosing treatment.

Conclusions

Among insured prostate cancer patients treated at a large academic medical center, few had knowledge of OOPE prior to making treatment choices.

Keywords: prostate cancer, out-of-pocket expenses, qualitative research, treatment decision

INTRODUCTION

Over 1.1 million men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in the next five years, the vast majority with localized disease.1 Prostate cancer accounts for nearly 10% of the total cost of cancer care to Medicare and exceeds $12 billion annually.2 Treatment options include radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, brachytherapy, and expectant management. Initial treatment costs can be substantial and payments vary widely among public and private insurance plans.3–6

Increasing costs of cancer care pose a serious financial burden even to patients with health insurance.7–9 A national survey of cancer patients showed that among those with insurance, 25% reported that they had used up all or most of their savings dealing with cancer, and 33% reported a problem paying their cancer bills.10 For patients with prostate cancer, little research has described their knowledge of and attitudes toward cost sharing or “out-of-pocket expenses” (OOPE). Furthermore, the extent to which the out-of-pocket costs of care are transparent to patients as they make treatment decisions is unclear.

Therefore, we conducted a qualitative research study of patients recently treated for clinically localized prostate cancer to understand their perceptions of treatment-related OOPE and to what extent OOPE influenced their treatment decisions.

METHODS

Setting

The patient population of the urology and radiation oncology clinics at the University of Pennsylvania is diverse — approximately 35% of those eligible for prostate cancer treatment are black and the facilities are located near medically underserved areas of the metropolitan area of Philadelphia. The institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania approved the study protocol.

Study Population

We recruited patients with clinically localized prostate cancer who had been treated within the past 6 to 18 months with surgery or external beam radiotherapy. We excluded patients who had received androgen deprivation therapy, did not speak English or who were cognitively impaired.

Recruitment

We prospectively enrolled patients between October 2010 and October 2011. Trained interviewers reviewed the medical records of patients scheduled with any of the urologists or genitourinary radiation oncologists. We used purposive sampling to ensure a diverse sample based on age, race, and treatment. A sample size was not determined a priori as enrollment was continued until theoretical saturation was reached11 i.e. when additional interviews yielded no new information about patients’ motivations or concerns. Forty-three eligible patients were approached for enrollment, and forty-one patients agreed to participate in the study. Two patients declined enrollment due to scheduling conflicts.

Interviews and Survey

The interviewer, trained in semi-structured interviewing methods, introduced the study, obtained verbal informed consent, and conducted audio-recorded interviews. The interviewer asked a series of open-ended questions to understand the patient’s knowledge of and attitudes toward OOPE for prostate cancer treatment and the effect of OOPE on treatment choice. At each step, patients were asked to provide feedback or elaborate in order to identify, refine, and clarify important themes. For example, when asked whether out-of-pocket costs of different prostate cancer treatments affected treatment choice, patients responded that they knew very little about their OOPE. Thus, we explored the extent to which patients knew about anticipated OOPE prior to treatment choice and with whom OOPE was discussed.

A review of the literature demonstrated a limited but growing literature to assess patients’ knowledge of and attitudes toward OOPE for cancer treatment.12–15 Therefore, we developed a patient questionnaire based on previous work and pilot patient interviews to further examine prostate cancer patients’ attitudes toward OOPE. The final survey included three items about the doctor’s role in discussing OOPE, three items about the burden of OOPE, one item about prior knowledge of OOPE, and two items effect of OOPE on treatment. Responses to survey items were graded on 5-point Likert scales.

Data analysis

Interview transcripts were reviewed using thematic analysis and constant comparison techniques.11 Using MAXQDA 10 (VERBI Software, Marburg, Germany), we perused transcripts and categorized segments of texts using assigned codes. The use of coding facilitates a systematic cataloguing to organize concepts within the framework of their development.16 We used constant comparison techniques to compare each transcript with previously coded text to ascertain whether new text segments conveyed similar versus novel concepts. This qualitative methodology allowed us to refine existing concepts and systematize new themes.16 Survey responses were trichotomized and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics for 41 respondents are displayed in Table I. More than half of the respondents were white (63%, 26/41), had college education (71%, 29/41), and had an annual income of $60,000 or more (58%, 24/41). Fifty-six percent (23/41) of patients received open or robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy, and 39% (16/39) received external beam radiation. Of the black men (37%, 15/41), most (60%, 9/15) had high school or less education and nine (60%, 9/15) and reported an annual income of $30,000 or less. All patients had health insurance; 7% (3/41) had Medicaid. Eight patients (20%, 8/41) expressed having problems paying medical bills. The median patient reported OOPE over the past 12 months was $640 (interquartile range $270–$1,500; for deductible and co-payment for treatment, supplies, drugs, and labs).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Study Population (n=41)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Treatment | |

| Open Surgery | 4 (10) |

| Robotic Surgery | 19 (46) |

| External Beam Radiation | 16 (39) |

| Open/Robotic Surgery and Radiation | 2 (5) |

|

| |

| Age range | |

| <45 | 0 |

| 45–54 | 7 (17) |

| 55–64 | 21 (51) |

| 65–74 | 12 (29) |

| >75 | 1 (2) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| White | 26 (63) |

| Black | 15 (37) |

|

| |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 12 (29) |

| College or more | 29 (71) |

|

| |

| Marital status | |

| Now married | 31 (76) |

| Divorced | 6 (15) |

| Widowed | 1 (2) |

| Never married | 3 (7) |

|

| |

| Employment status | |

| Employed for wages | 18 (37) |

| Self-employed | 3 (11) |

| Out of work | 2 (6) |

| On disability | 5 (11) |

| Retired | 12 (31) |

| Unable to work | 1 (3) |

|

| |

| Income | |

| ≤$10,000 | 3 (7) |

| $10,001–30,000 | 7 (17) |

| $30,001–60,000 | 7 (17) |

| $60,001–100,000 | 7 (17) |

| >$100,000 | 15 (37) |

| I don’t know | 2 (5) |

|

| |

| Insurance | 41 (100) |

| Paid by an employer | 28 (68) |

| Paid by self/family | 3 (7) |

| Medicare | 7 (17) |

| Medicaid | 3 (7) |

|

| |

| Problem paying medical bills | |

| Yes | 8 (20) |

| No | 33 (80) |

Qualitative Interviews

Qualitative assessment revealed several recurring themes, which are exhibited in Figure 1 and explained below using illustrative quotes.

“My insurance takes care of it”

Figure 1.

Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Out-of-Pocket Expenses

More than half of the patients (25/41, 61%) articulated having no concern for the cost of treatment because of insurance. “There wasn’t any difficulty [with affording OOPE],” one patient explained, “the bills were submitted to Medicare, [and] Medicare paid the bills.” Another patient stated, “It [the actual cost of treatment] was covered by insurance, so that wasn’t a problem.”

About one in five patients (11/41, 27%) recognized the magnitude of their hospital bills and conveyed gratitude. All of them used one of three words — “fortunate,” “lucky,” or “grateful.” One patient stated, “I’ve been very fortunate, and you will never hear me say a word about our current medical system. It worked great for me.” In the same vein, another commented that he “considers [himself] lucky [he] didn’t have to pay more.”

“Health is more important than cost”

More than half of the patients (21/41, 51%) expressed that their health is more important than the cost of medical treatment. One patient shared, “When you are talking about your life, it doesn’t matter what it costs.” Similarly, another patient stated, “The key thing is just to survive the cancer, and the quicker you get the cancer removed from your system, the better off you are going to be.” Overall, most patients appear to place a higher priority on dealing with the illness than with cost. “The decision was based on a lot of things and finances were way down the list,” one said.

“I didn’t look into it”

When choosing treatment options, considerations for out of pocket payments are often dismissed, according to more than one third of the patients (14/41, 34%). Many said that it “didn’t matter” or that they “didn’t look into it.” One commented, “I never considered it to be perfectly honest.” Another shared, “I didn’t talk about it and didn’t ask about it a lot. I guess I wondered at some on it but if I had been really worried I would have asked more.”

“I can’t afford it but would have chosen the same treatment”

In contrast to the majority of the patients who said they had no problem paying their medical bills, nine patients (9/41, 22%) explicitly expressed that their share of out-of-pocket cost was burdensome or that their finances were affected. Still, like the majority of the patients, their treatment choices in retrospect would have been unaffected despite their burdensome perception of OOPE.

One pointed out the necessity of having supplemental income in order to afford his care by saying, “If you are not getting enough Social Security, you have to do something. Collect cans, like I did, cans, refrigerators and junk. There’s good money in that.” Another patient said, “I had no options. I can’t afford it… I know I have a lot bills at the house.”

Some patients were forced to sacrifice other spending to pay for their OOPE, as one patient said, “We don’t go out to eat like we used to… We watch it a little bit more simply because I’m not working and … I didn’t get any money from [disability] for a month and a half.” Another man said, “…just tightening the budget and cutting back on Christmas this year.”

“It’s not my doctor’s business”

Several patients (7/41, 17%) asserted that matters regarding out-of-pocket costs are irrelevant to their doctor’s job. One patient said, “I don’t know that [my doctor] knows [about how much I am spending on OOPE] but it didn’t matter if he knew or didn’t know,” while another said, “Those guys live in a different world.” Some patients seemed to believe that doctors are supposed to manage their patients’ health, and not financial, issues; one patient stated, “I would rather him concentrate on the medical,” as another added, “[Explaining about OOPE] is not what he is here for.”

Survey Responses

Patients’ responses to the survey portion of the interview are displayed in Table II. The majority (73%, 30/41) of patients reported that they did not feel burdened by OOPE. 80% (33/41) of patients reported that they “knew little” or “did not know” their likely out-of-pocket costs for different treatment prostate cancer treatments before choosing treatment. Similarly, 83% (34/41) reported that out-of-pocket costs did not affect their treatment choice. The great majority of patients (93%, 38/41) reported that, in retrospect, they would not have chosen a different treatment even if they had known the actual cost of the given treatment.

TABLE 2.

Out-of-Pocket Expenses Survey Responses

| Survey item | Strongly Agree/ Agree n (%) | Neither Agree nor Disagree n (%) | Strongly Disagree/ Disagree n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor’s Role | |||

| I would like my doctor to talk about my out- of-pocket expenses when he/she recommends a treatment. | 25 (61) | 11 (27) | 7 (17) |

| My prostate doctor should consider my out- of-pocket costs as he/she makes medical decisions. | 13 (32) | 8 (20) | 20 (49) |

| My prostate doctor should consider the country’s healthcare costs as he/she makes medical decisions. | 15 (37) | 8 (20) | 18 (44) |

| Burden of Out-of-Pocket Cost | |||

| I feel burdened by my out-of-pocket medical costs for prostate cancer. | 10 (24) | 1 (2) | 30 (73) |

| I am forced to cut other spending (like groceries or gas) to pay for my out-of-pocket costs for my cancer treatment. | 8 (20) | 0 | 33 (80) |

| In the past 12 months, I have had to make sacrifices to afford OOPE. | 8 (20) | 0 | 33 (80) |

| Prior Knowledge* | |||

| I knew about the likely out-of-pocket costs for different prostate cancer treatments before choosing treatment. | 2 (5) | 6 (15) | 33 (80) |

| Effect of Costs on Treatment | |||

| The out-of-pocket costs of different prostate cancer treatments affected my treatment choice. | 2 (5) | 5 (12) | 34 (83) |

| If I had known the actual out-of-pocket treatment costs, I would have chosen a different treatment. | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 38 (93) |

For this item, response categories from left to right are “Knew Exactly or a Lot,” “Knew a Fair Amount,” and “Knew Little or Did Not Know.”

Of the 9 patients who expressed feeling burdened by OOPE, the majority were black (7/9), had less than college education (6/9), earned an annual income less than $60,000 (6/9), and reported OOPE exceeding $1,500 (6/9). A portion (3/9) reported earning an annual income between $60,000 and $100,000. Despite feeling burdened by OOPE, only 2 reported that they would have chosen a different treatment had they known the actual out-of-pocket treatment costs.

DISCUSSION

We undertook this study to examine prostate cancer patients’ knowledge and attitudes toward treatment-related OOPE and whether OOPE affect patients’ treatment choice. Among a cohort of men seen in the urologic and radiation oncology practices of a large academic center, we found that OOPE do not play a substantial role in the majority of patients’ prostate cancer treatment choices, even among the subgroup of patients for whom OOPE are burdensome.

Our findings are consistent with and extend previous research on patient attitudes toward OOPE. In the cohort under study, patients with localized prostate cancer appear to consider cancer treatment (surgery or radiation therapy) akin to a ‘sacred good,’ more important than, and unaffected by, the costs of treatment. Similarly, investigators have found that patients with end-stage cancer considering the costs of chemotherapy prioritize aggressive treatment over other factors such as cost, severity, and adverse treatment effects.17–21 Comparable sentiment can be elicited from physicians; 78% of academic medical oncologists indicate that patients should have ‘effective’ treatment regardless of cost.22

Almost all patients had either employer-sponsored medical insurance or Medicare/Medicaid, and self-reported OOPE were similar in magnitude to other studies of prostate cancer OOPE.15 Previous work has demonstrated that when medical costs are covered by Medicare, patients choose to receive medical care even if the probability of positive outcome is low.23,24 Our study extends this literature to demonstrate that insured patients with prostate cancer are largely insensitive to OOPE associated with different prostate cancer treatment options.

Previous studies have found that OOPE are substantial and distressing for patients.25,26 Similarly, in our study, a subgroup of patients found OOPE to be burdensome. Not surprisingly, a large portion of these patients reported annual incomes of less than $30,000 per year. However, we also found that OOPE were burdensome even to a group of patients with annual incomes between $60,000 and $100,000, a range most consistent with the American middle class.27 While we did not specifically ask these patients for further explanation, it is possible that their sense of economic vulnerability in the context of cancer care was exacerbated by the effects of the recent global economic downturn.28

Despite recent calls for greater transparency in cost sharing for cancer treatment12,29,30, the vast majority of patients report having little knowledge of OOPE prior to making cancer treatment decisions. While nearly all patients reported in retrospect that OOPE would not have affected their treatment choice, it is impossible to know how ‘real-time’ cost transparency (e.g. incorporating treatment costs into discussions of treatment effectiveness) may affect health care decision making or the doctor-patient relationship. Our study and others demonstrate that OOPE can be burdensome and distressing to patients who report a wide swath of incomes. Moreover, our study did not include patients who were under or uninsured; for such patients OOPE may represent nearly the full burden of treatment costs and could likely (and not surprisingly) exert excessive influence on treatment decisions. We will better understand the effect of OOPE on cancer treatment decisions only by examining ‘real-time’ cost transparency in the context of patient-centered decision-making research.

For example, to begin to address the profound knowledge gap around OOPE, researchers could explore the use of a simple screening question at cancer patients’ initial consultation to understand their desire to learn more about anticipated OOPE associated with various treatment options prior to treatment choice. Moreover, communication models have been proposed to reduce patients’ potential reticence to discuss treatment costs.12 However, limited guidance exists to determine whom in the care provider team can most effectively engage patients about treatment costs. Indeed, a small group of prostate cancer patients expressed unease that their physicians would address treatment costs during consultations. For such patients, non-physician care team members, such as financial advisors, social workers, or office managers, may be better suited to discuss treatment costs.31 The success of future efforts aimed at the laudable goal of participatory decision-making will require researchers to design and test methods to optimally frame these discussions and to train physicians and other health care team members on best practices to achieve cost transparency.

Our study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. The cohort for this study was drawn from a single, academic, urban institution. While diverse, the cohort has limited generalizability to other care settings. For example, the proportion of study participants with incomes over $100,000 is substantially greater than in the general population; the relative affluence of the cohort, and their insured status, could partially explain their unburdened sentiment towards OOPE. In addition, the sample size was guided by qualitative research methods, precluding meaningful statistical evaluation among patient characteristics. Lastly, self-reported responses to qualitative and survey assessment of OOPE are subject to recall bias.

In conclusion, for the majority of prostate cancer patients in this single institution study, OOPE did not play an important role in the treatment decision-making process – few prostate cancer patients had knowledge of OOPE prior making treatment choices. The subgroup of patients who were burdened by OOPE was socioeconomically diverse; despite their financial hardship, they reported that OOPE would not have affected their prostate cancer treatment choices.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a grant from the Leonard Davis Institute for Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Bekelman is supported by an institutional Paul Celebresi National Cancer Institute Career Development Award (K12-CA076931).

Role of the Sponsors: The funding agencies did not participate in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

We are grateful to David Asch, MD MBA and Caleb Alexander, MD for insightful comments in the design and analyses stages of the study.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Bekelman had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Bekelman, Pauly

Acquisition of data: Mehler, Jung

Drafting of the manuscript: Jung, Mehler, Bekelman

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Jung, Guzzo, Lee, Mehler, Christodouleas, Deville, Hollis, Shah, Vapiwala, Wein, Pauly, Bekelman

Statistical analysis: Jung, Bekelman

Study supervision: Bekelman

Financial Disclosures: None

Disclaimer: The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Obtained funding: Bekelman

Administrative, technical, or material support: Mehler, Guzzo, Lee, Christodouleas, Deville, Hollis, Vapiwala, Wein, Bekelman

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chan JM, Jou RM, Carroll PR. The relative impact and future burden of prostate cancer in the United States. The Journal of urology. 2004 Nov;172(5 Pt 2):S13–16. discussion S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011 Jan 19;103(2):117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollack A. New York Times. Dec 26, 2007. Cancer Fight Goes Nuclear, With Heavy Price Tag. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein J. The Wall Street Journal. Dec 17, 2008. CyberKnife for Prostate Cancer: Geography Is Destiny. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wysocki B. The Wall Street Journal. Feb 26, 2004. Robots assist heart surgeons: With guidance of surgeons, four-armed devices make tricky incisions in operations. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolata G. The New York Times. Aug 11, 2009. Survey Finds High Fees Common in Medical Care. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauly MV. Is high and growing spending on cancer treatment and prevention harmful to the United States economy? Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007 Jan 10;25(2):171–174. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.7536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009 Jun 10;27(17):2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Aug 10;27(23):3868–3874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.USA Today KFF, Harvard School of Pubic Health. National survey of households affected by cancer. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corbin JE, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Tseng CW, et al. Barriers to patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Aug;19(8):856–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Meltzer DO. Patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. JAMA. 2003 Aug 20;290(7):953–958. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrag D, Hanger M. Medical oncologists’ views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: a pilot survey. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Jan 10;25(2):233–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayadevappa R, Schwartz JS, Chhatre S, et al. The burden of out-of-pocket and indirect costs of prostate cancer. The Prostate. 2010 Aug;70(11):1255–1264. doi: 10.1002/pros.21161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health services research. 2007 Aug;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson JF. Cancer care: a microcosm of the problems facing all of health care. Annals of internal medicine. 2009 Apr 21;150(8):573–576. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-8-200904210-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuyama R, Reddy S, Smith TJ. Why do patients choose chemotherapy near the end of life? A review of the perspective of those facing death from cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006 Jul 20;24(21):3490–3496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottlieb S. Chemotherapy may be overused at the end of life. BMJ. 2001 May 26;322(7297):1267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balmer CE, Thomas P, Osborne RJ. Who wants second-line, palliative chemotherapy? Psycho-oncology. 2001 Sep-Oct;10(5):410–418. doi: 10.1002/pon.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slevin ML, Stubbs L, Plant HJ, et al. Attitudes to chemotherapy: comparing views of patients with cancer with those of doctors, nurses, and general public. BMJ. 1990 Jun 2;300(6737):1458–1460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6737.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadler E, Eckert B, Neumann PJ. Do oncologists believe new cancer drugs offer good value? The oncologist. 2006 Feb;11(2):90–95. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-2-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chao LW, Pagan JA, Soldo BJ. End-of-life medical treatment choices: do survival chances and out-of-pocket costs matter? Medical decision making : an international journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making. 2008 Jul-Aug;28(4):511–523. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07312713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong YN, Hamilton O, Egleston B, et al. Understanding how out-of-pocket expenses, treatment value, and patient characteristics influence treatment choices. The oncologist. 2010;15(6):566–576. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markman M, Luce R. Impact of the cost of cancer treatment: an internet-based survey. Journal of oncology practice / American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Mar;6(2):69–73. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathews M, Park AD. Identifying patients in financial need: cancer care providers’ perceptions of barriers. Clinical journal of oncology nursing. 2009 Oct;13(5):501–505. doi: 10.1188/09.CJON.501-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chinni D. One more Social Security quibble: Who is middle class? May 10, [Accessed September 11, 2006]. 2005 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollack CE, Lynch J. Health status of people undergoing foreclosure in the Philadelphia region. American journal of public health. 2009 Oct;99(10):1833–1839. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bach PB. Costs of cancer care: a view from the centers for Medicare and Medicaid services. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007 Jan 10;25(2):187–190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller CC. The New York Times. 2010. Jun 11, Bringing Comparison Shopping to the Doctor’s Office. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Back A. Talking with patients about the cost of cancer care. Journal of Oncology Oractice. 2007 May;3(3):122–123. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0732504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]