Summary

Arterial stiffening is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, but how arteries stay supple is unknown. Here, we show that apolipoprotein E (apoE) and apoE-containing HDL maintain arterial elasticity by suppressing the expression of extracellular matrix genes. ApoE interrupts a mechanically driven feed-forward loop which increases the expression of collagen-I, fibronectin, and lysyl oxidase in response to substratum stiffening. These effects are independent of the apoE lipid-binding domain and transduced by Cox2 and miR-145. Arterial stiffness is increased in apoE-null mice, this stiffening can be reduced by administration of the lysyl oxidase inhibitor, BAPN, and BAPN treatment attenuates atherosclerosis despite highly elevated cholesterol. Macrophage abundance in lesions is reduced by BAPN in vivo, and monocyte/macrophage adhesion is reduced by substratum softening in vitro. We conclude that apoE and apoE-containing HDL promote healthy arterial biomechanics, and this confers protection from cardiovascular disease independent of the established apoE-HDL effect on cholesterol.

Introduction

The mechanobiology of cells and tissues is a rapidly developing field of importance to development, physiology and disease (Davies, 2009; Discher et al., 2005; Egeblad et al., 2010; Garcia-Cardena and Gimbrone, 2006; Schwartz and DeSimone, 2008). Increases in tissue stiffness and intracellular tension are common features of fibrosis-associated processes such as wound repair, cancer, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Duprez and Cohn, 2007; Levental et al., 2009). A recurring theme in these processes is remodeling of the ECM. Increased ECM synthesis is mediated by fibrotic factors such as TGF-β and PGF2 (Border and Noble, 1994; Oga et al., 2009), but whether anti-fibrotic factors exist to antagonize aberrant ECM gene expression and maintain normal tissue elasticity is poorly understood.

Mechanical forces play a major role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (Davies, 2009; Garcia-Cardena and Gimbrone, 2006; Gimbrone et al., 2000). As a result of disturbed blood flow patterns at sites of arterial curvature and branches, endothelial cell integrity is disrupted focally, ultimately allowing for entry of blood monocytes into the vessel. These monocytes develop into macrophages and foam cells, a process exacerbated by high cholesterol, and then secrete cytokines that act on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) to promote their dedifferentiation to a migratory and proliferative phenotype. Dedifferentiated VSMCs synthesize large amounts of ECM components (in particular, fibrillar collagens and elastin) and matrix-modifying enzymes that remodel the local ECM (Owens et al., 2004; Thyberg et al., 1997; Thyberg et al., 1990). Elastin makes arteries more compliant to large deformations, and fibrillar collagens make arteries stiffer (Diez, 2007; Lakatta, 2007). The mechanical properties of elastin and fibrillar collagens depend upon their crosslinking by the lysyl oxidases (Csiszar, 2001; Kagan and Li, 2003). VSMCs produce lysyl oxidase and are therefore poised to be major regulators of matrix remodeling and arterial stiffness.

Arterial stiffness increases with normal aging, and this process is exaggerated by the metabolic syndrome and diabetes (Lakatta, 2007; Stehouwer et al., 2008). Arterial stiffness is also a cholesterol-independent risk factor for a first cardiovascular event (Mitchell et al., 2010). Arterial stiffness is determined by vascular tone and the amount and composition of the ECM. While regulators of vascular tone have been very well studied (Bellien et al., 2008), little is known about effectors and mechanisms that might regulate arterial stiffness by limiting ECM production. Nor is it known if arterial stiffening is a cause or consequence of cardiovascular disease.

Here we show that the expression of ECM genes in VSMCs and arterial stiffness is potently suppressed by apolipoprotein E (apoE) and apoE-containing HDL (apoE-HDL). ApoE-HDL has a well-established role in removing cholesterol from peripheral cells and delivering it to the liver in a process called reverse cholesterol transport, but several reports using cultured cells have indicated that the effects of apoE extend beyond regulation of plasma lipid levels (Ishigami et al., 1998; Ishigami et al., 2000; Kothapalli et al., 2004; Swertfeger and Hui, 2001; Symmons et al., 1994). Early in vivo studies even suggested that a lipid-independent effect of apoE could protect against atherosclerosis (Thorngate et al., 2003) though the basis for this observation has remained elusive. We now show that the inhibitory effect of apoE-HDL on ECM gene expression and arterial stiffening is cholesterol-independent and sufficient to attenuate atherosclerosis. Thus, in addition to its established effect on reverse cholesterol transport, HDL contributes to healthy arterial biomechanics, and this effect is causal for cardiovascular protection.

Results

ECM gene expression suppressed by apoE and HDL

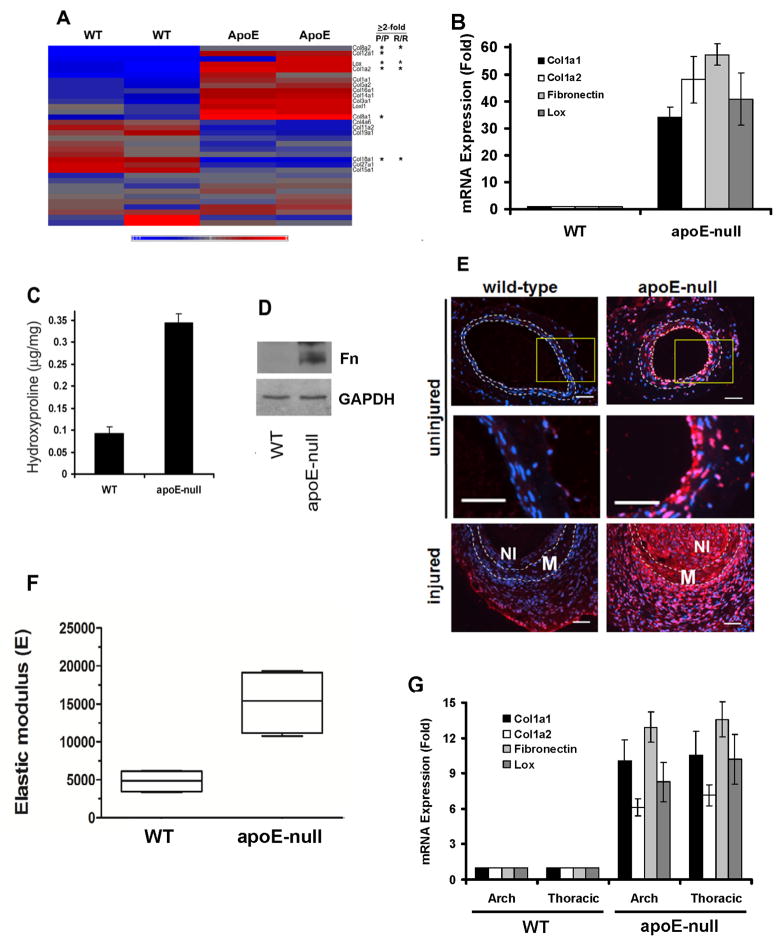

We interrogated GEO dataset GSE13865 which transcript profiled atherosclerosis-prone and -resistant regions of 4-mo wild-type (WT) and apoE-null mouse aortae (Fig. 1A). Genes that were differentially expressed in the athero-prone regions were identified and subjected to enrichment analysis against the Gene Ontology (GO) database. This analysis ranked “Extracellular Region” (GO: 0005576) and “Extracellular Region Part” (GO: 0044421) as the most enriched within the “Cellular Component” (GO: 0005575) functional grouping (Fig. S1A). Within the “Extracellular Region Part,” two functional groups were highly enriched: the “Extracellular Matrix” (GO: 0031012) and “Plasma Lipoprotein Particles” (Fig. S1B), the latter of which was expected given the deletion of apoE. Several collagen genes, including the highly expressed type I collagen, were differentially expressed in apoE-null aortae (Table S1A and Fig. 1A asterisks).

Figure 1. Altered ECM gene expression in apoE-null mice.

(A) Heat map of collagen and Lox genes in WT and apoE-null aortae. Duplicates represent Agilent dye-swaps. Asterisks indicate fold-change ≥2 in athero-prone (P/P) and resistant (R/R) regions. Scale: −0.9–1.0. (B) Cleaned aortae from 6-mo male WT and apoE-null mice analyzed by RT-qPCR. Results show mean ± SE, n=4. P-0.012 by 2-tailed t-test. (C–D) Cleaned aortae analyzed for hydroxyproline content (mean ± SD, n=3) or western blotted for FN, respectively. (E) Lox immunostaining (red) of uninjured and injured femoral arteries. DAPI-stained nuclei are shown in blue. Dashed lines show the IEL and EEL. M; media. NI; neointima. Middle panels show enlargements of boxed regions. Scale bar = 50 μm. (F) Thoracic aortae of four 6-mo WT and four apoE-null mice were cleaned of adventitia, opened longitudinally, and analyzed by AFM, indenting into the luminal surface at >20 distinct non-lesioned locations. The mean elastic modulus was calculated for each mouse and graphed as a Tukey box and whisker plot; p=0.029 by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test. (G) Cleaned aortae from 6-mo male WT and apoE-null mice were divided into arch (ascending) and thoracic (descending) regions. RNA was isolated from the aortae and analyzed by RT-qPCR for collagen-I, FN, and Lox gene expression. Results are normalized to 18S rRNA. Results show mean ± SE, n=5. p=0.036 by 2-tailed t-test. See also Figure S1 and Table S1A–C.

The effect of apoE knock-out on several collagen genes was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Fig. 1B and Table S1B). RT-qPCR also revealed an apoE-dependent regulation of FN mRNA that was not detected by transcript profiling (Fig. 1B). Collagen protein (measured as hydroxyproline content) and FN protein levels were increased in the aortae of apoE-null mice as compared to WT controls (Fig. 1C and D, respectively). Similarly, increased collagen-I protein was readily detected in the media and neointima of immunostained aortic root sections from apoE-null, but not WT, mice (Fig. S1C). In contrast, elastin mRNA levels were not strongly affected by deletion of apoE (Fig. S1D and Tables S1A and S1C).

Lysyl oxidase (Lox) crosslinks adjacent collagen triple helices and confers tensile strength to the collagen fibril (Csiszar, 2001; Kagan and Li, 2003). Our transcript profiling analysis revealed an increase in the expression of Lox mRNA in apoE-null arteries as compared to WT (Fig. 1A; asterisk). Lox mRNA and protein induction in apoE-null arteries was confirmed by RT-qPCR and immunostaining (Fig. 1B and E, respectively, and Table S1A). Note the increased Lox protein in apoE-null vs. WT arteries (Fig. 1E top and middle panels), and even greater increased expression in the media and neointima of apoE-null mice after fine wire femoral artery injury (Fig. 1E, bottom panels). In contrast, the gene expression of procollagen-lysine,2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 3 (PLOD3), which catalyzes the hydroxylation of lysine residues in collagens, was similar in WT and apoE-null arteries (Fig. S1E). Upregulation of collagen-I protein and enhanced crosslinking by elevated Lox expression has the potential to increase tissue stiffness, and, indeed, atomic force microscopy (AFM) in force mode showed an increase in the median elastic modulus of apoE-null femoral arteries as compared to WT controls (Fig. 1F). Further studies focused on collagen-I and Lox, which regulate tensile strength and tissue elasticity, and FN which interacts with collagen functionally and has been associated with stiffness-dependent cell proliferation (Bruel et al., 1998; Kadler et al., 2008; Kagan and Li, 2003; Klein et al., 2009).

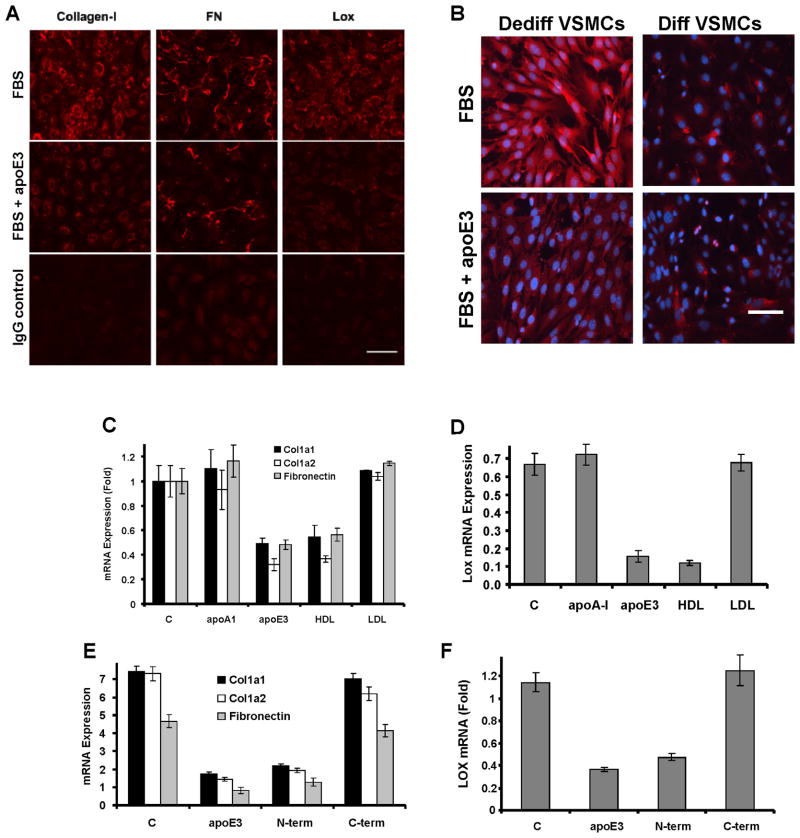

Deletion of apoE in mice leads to hyperlipidemia and spontaneous atherosclerosis as well as an exaggerated response to vascular injury (Ali et al., 2007; Matter et al., 2006; Piedrahita et al., 1992; Plump et al., 1992). Since VSMCs de-differentiate at sites of injury and atherosclerotic lesion formation and begin to produce relatively large amounts of ECM, we considered the possibility that the matrix-regulatory effects detected in apoE-null mice were secondary to lesion formation. However, several lines of evidence collectively indicated that the changes we observed in collagen-I, FN, and Lox gene expression were not merely consequences of disease. First, we could restore apoE expression in the liver of young apoE-null mice by infection with AAV-apoE3 (Kitajima et al., 2006), and this resulted in near WT levels of Col1a1, Col1a2, FN, and Lox gene expression quickly (within 2 weeks; compare Fig. S1F-G to S1H-I). Second, the Col1a2, FN, and Lox genes were similarly upregulated in athero-resistant as well as athero-prone regions of the apoE-null aortae as compared to WT (Fig. 1A, asterisks, Fig. 1G, and Table S1C). Third, purified apoE3, at a physiological concentration (Wientgen et al., 2004), reduced levels of Col1a1, Col1a2, FN, and Lox protein (Fig. 2A–B) and mRNAs (Fig. 2C–F) in cultured VSMCs: these effects were specific to dedifferentiated VSMCs (Fig. 2B) and dose- and time-dependent (Fig. S2A–D). We conclude that apoE has a primary suppressive effect on expression of the VSMC collagen-I, FN, and Lox genes. A similar pattern of inhibition was seen in human VSMCs but not human aortic endothelial cells (Fig. S2E–F).

Figure 2. ApoE and HDL inhibit ECM expression in dedifferentiated VSMCs.

(A) Serum-starved VSMCs isolated from wild-type mice were incubated with 10% FBS in the absence (control; C) or presence of 2 μM apoE3 for 24 h. The cells were fixed and stained for collagen-I, FN or Lox and visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy. Scale bar=50μm. The IgG control used FBS-stimulated cells. (B) VSMCs were isolated from C57BL/6 aortae by explant cultures (dedifferentiated phenotype) or by collagenase digestion (differentiated phenotype). Asynchronous cells of each phenotype were incubated with 10% FBS in the absence (control; C) or presence of 2 μM apoE3 for 24 h and then stained for collagen-I (red). Blue: dapi-stained nuclei. Scale bar=50μm. The figure shows a representative result. (C–D) Serum-starved VSMCs isolated from WT mice were incubated with 10% FBS in the absence (control, C) or presence of 2 μM apoA-I or apoE3 or 50 μg/ml HDL or LDL for 24 h. RNA levels were determined by RT-qPCR. (E–F) The experiment in C–D was repeated except we compared the effects of 2 μM apoE3 to its N- and C-terminal fragments. RT-qPCR results show mean ± SD of duplicate PCR reactions and are representative of at least three independent experiments. See also Figure S2.

The majority of apoE circulates as a component of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and HDL, but apoE is not present in LDL. We therefore compared HDL and LDL for their abilities to regulate matrix protein gene expression in primary mouse VSMCs. HDL efficiently suppressed collagen-1, FN, and Lox gene expression while LDL failed to inhibit these genes (Fig. 2C–D). ApoA-I, the major apolipoprotein in HDL, was unable to decrease expression of these matrix genes (Fig. 2C–D), nor was HDL after depletion of apoE (Fig. S2G). All three isoforms of human apoE inhibited ECM gene expression (Fig. S2H). Thus, suppression of collagen-I, FN, and Lox gene expression is a selective property of apoE and apoE-containing HDL rather than a general property of apolipoproteins and lipoproteins. ApoE3 consists of a 22 kD N-terminal domain which binds to the LDL receptor and a 10 kD C-terminal domain required for lipid binding and regulation of reverse cholesterol transport (Weisgraber, 1994). Expression of Col1a1, Col1a2, FN, and Lox mRNAs were all repressed by the N-terminal domain but not by the C-terminal lipid-binding domain of apoE3 (Fig. 2E–F).

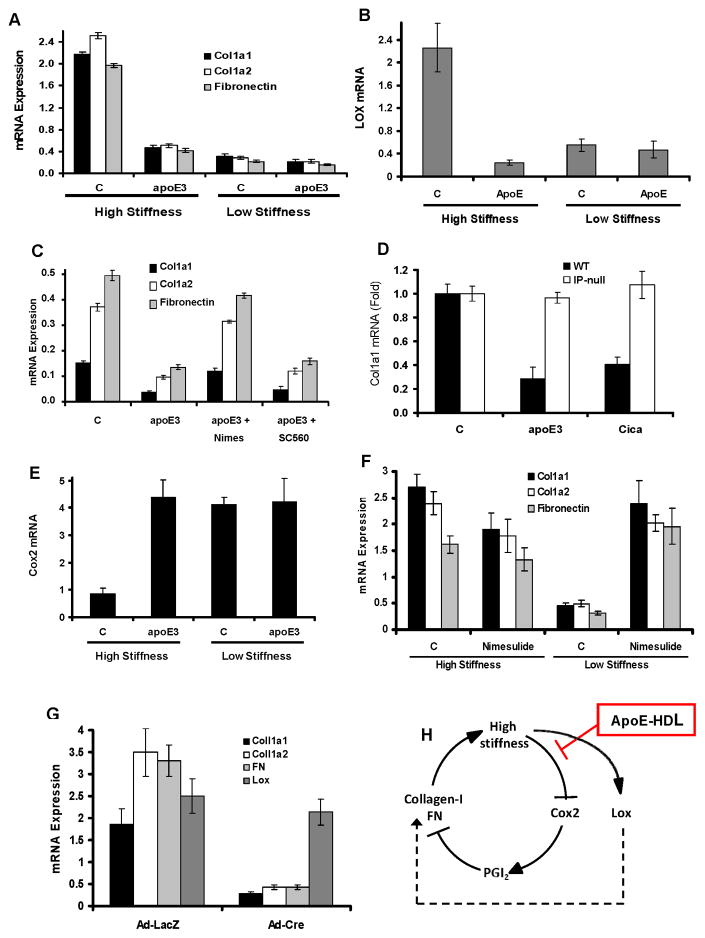

Mechano-sensitive collagen-I and fibronectin gene expression regulated by Cox2 and circumvented by apoE

Collagen-I expression correlates directly with ECM stiffness in fibroblasts (Liu et al., 2010). We therefore asked if the effects of apoE on ECM gene expression might be affected by substratum stiffness itself. VSMCs were cultured on biocompatible FN-coated polyacrylamide hydrogels prepared with elastic moduli that span the stiffness range of healthy and diseased arteries [~2000 and 25,000 Pascal (Klein et al., 2009); hereafter called low and high stiffness, respectively]. The expression of Col1a1, CoI1a2, FN, and Lox mRNAs (Fig. 3A–B) as well as Lox enzymatic activity (Fig. S3A) were all positively regulated by substratum stiffness, and this stiffness-dependent upregulation was blocked by apoE3 (Fig. 3A–B and S3A). We conclude that apoE is an inhibitor of mechanosensitive ECM gene expression.

Figure 3. Mechano-sensitive gene expression regulated by apoE.

(A–B) Serum-starved primary mouse VSMCs were incubated with 10% FBS in the absence (control, C) or presence of 2 μM apoE3 on high stiffness or low stiffness FN-coated hydrogels for 24 h. (C) the experiment in A–B was repeated except that apoE-treated VSMCs on plastic were given 1 μM nimesulide (Nimes; Cox2 inhibitor) or 1 mM SC560 (Cox1 inhibitor). (D) The experiment in C was repeated using WT and IP-null VSMCs treated with 2 μM apoE3 or 200 nM cicaprost (Cica; stable PGI2 mimetic). (E) The experiment in A was analyzed for Cox2 mRNA. (F) Serum-starved primary mouse VSMCs were incubated with 10% FBS in the absence (control, C) or presence of 1 μM nimesulide on high stiffness or low stiffness FN-coated hydrogels for 24 h. (G) Primary VSMCs were isolated from mice expressing Cre-dependent Cox2. The cells were seeded overnight on FN-coated cover slips, serum-starved, infected with adenoviruses encoding LacZ or Cre, and directly stimulated with 10% FBS for 24 h. For all panels, Col1a1, Col1a2, FN, Lox, or Cox2 mRNAs were quantified by RT-qPCR and plotted relative to 18S rRNA. For panels A–G, results show mean ± SD of duplicate PCR reactions and are representative of at least three independent experiments. (H) Model of the stiffness- and apoE-regulatory effects on Cox2, collagen-I, FN, and Lox expression. See also Figure S3.

Collagen-I gene expression is inversely proportional to the expression of Cox2 in fibroblasts (Liu et al., 2010) and VSMCs (Fig. 3A vs. 3E and Fig. S2E vs. S2F). Previously, we reported that apoE3 and its N-terminal domain stimulate the expression of Cox2 mRNA and protein in VSMCs (Ali et al., 2008; Kothapalli et al., 2004). Consistent with these results, the Cox2 inhibitor, nimesulide, prevented suppression of the collagen-I and FN genes by apoE3 in VSMCs whereas the Cox1 inhibitor, SC560, was without effect (Fig. 3C). Cox2 production in VSMCs leads to the production of PGI2, and VSMCs treated with apoE3 have increased amounts of PGI2 in their conditioned medium (Ali et al., 2008; Kothapalli et al., 2004). The PGI2 mimetic, cicaprost, phenocopied the effect of apoE3 on collagen-I and FN mRNAs (Fig. 3D and S3C–D), and these effects of apoE3 and PGI2 are linked mechanistically because deletion of the PGI2 receptor, called IP, prevented suppression of Col1a1, Col1a2, and FN mRNAs by apoE (Fig. 3D and S3C–D). Thus, regulation of VSMC collagen-I and FN gene expression by apoE is mediated by the Cox2-PGI2-IP signaling pathway.

If Cox2 is causally linked to the effect of apoE3 on mechanically-driven collagen-I and FN gene expression, then its response to apoE3 should be mechanosensitive. Indeed, we found that Cox2 levels (Fig. 3E) and activity (Fig. S3B) decline when VSMCs are cultured at a high stiffness characteristic of vascular lesions. ApoE3 prevents this downregulation and maintains elevated Cox2 gene expression (Fig. 3E) and enzymatic activity (Fig. S3B) despite substrate stiffening. Moreover, the apoE3 effect on mechanosensitive Cox2 expression can explain the suppressive effects of apoE3 on collagen-I and FN gene expression because i) Cox2 inhibition with nimesulide was sufficient to increase levels of collagen-I and FN mRNAs in cells cultured on a low stiffness substratum (Fig. 3F) and ii) ectopic expression of Cox2 was sufficient to reduce levels of collagen-I and FN mRNAs in VSMCs cultured on a rigid substratum (Fig. 3G). Thus, the downregulation of Cox2 on a stiff substratum leads to increased collagen-I and FN gene expression in VSMCs, and apoE limits synthesis of these ECM proteins by preventing the stiffness-dependent downregulation of Cox2 (Fig. 3H). Similar results were seen with collagen-coated hydrogels (Fig. S3E–F), indicating that the effects were stiffness- rather than matrix-protein specific.

We considered the possibility that the suppressive effects of apoE3 and/or a soft substratum on ECM genes might be due to increased VSMC differentiation because ECM synthesis is minimal in differentiated (also called “contractile”) VSMCs (Owens et al., 2004; Thyberg et al., 1997; Thyberg et al., 1990). However, three different markers of differentiated VSMCs were slightly decreased, rather than increased, in response to a low stiffness substratum (Fig. S3G) and apoE3 had no effect on SM-marker expression regardless of substratum stiffness (Fig. S3G). Thus, apoE3 directly controls mechanosensitive ECM production in dedifferentiated VSMCs rather than indirectly inhibiting ECM synthesis downstream of a primary effect on VSMC differentiation.

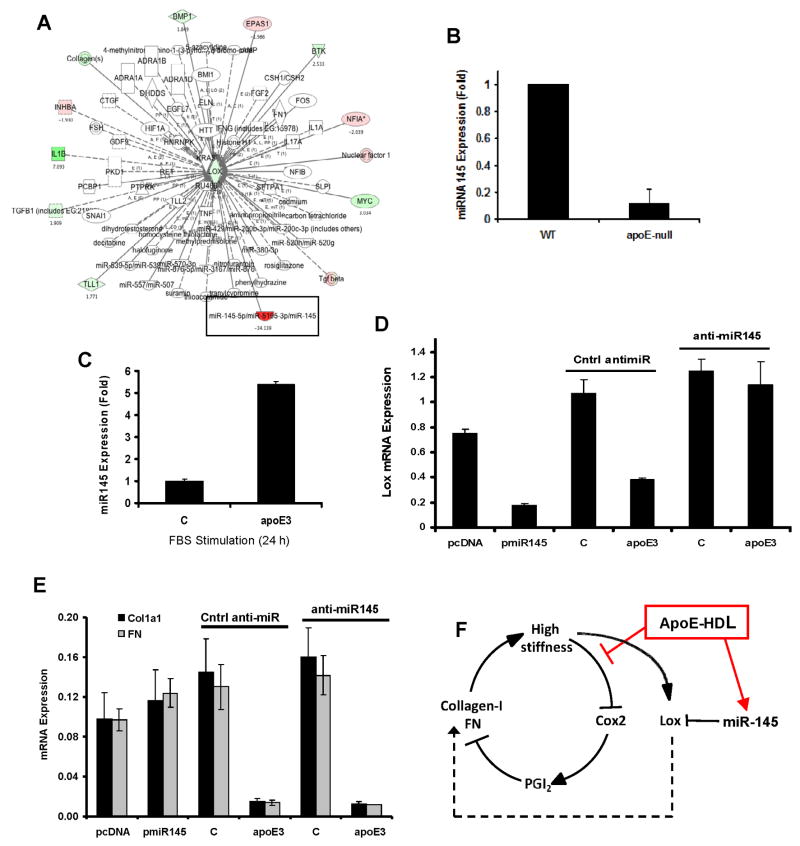

miR-145 mediates the suppressive effect of apoE on Lox gene expression

In contrast to collagen-I and FN, ectopic expression of Cox2 on a rigid substratum (Fig. 3G) or Cox2 inhibition on a soft substratum (Fig. S4A) failed to alter Lox gene expression. Deletion of IP (Fig. S4B) or inhibition of Cox2 also failed to overcome the inhibitory effect of apoE3 on Lox gene expression (Fig. S4C) or enzymatic activity (Fig. S4D). Thus, the effect of apoE3 on mechanosensitive Lox gene expression is Cox2-independent. We used a genome-wide approach to identify potential upstream regulators of Lox gene expression in vivo. We injured the femoral arteries of SMA-GFP transgenic mice, a line in which GFP levels are controlled by the α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) promoter (Yokota et al., 2006). Injury-induced VSMC proliferation can be visualized in this mouse line by the loss of GFP fluorescence because the SMA promoter is not expressed in proliferating (de-differentiated) VSMCs (Klein et al., 2009). We microdissected these GFP-negative femoral artery regions and determined global mRNA expression patterns relative to uninjured contralateral controls. Differentially expressed mRNAs and miRNAs were superimposed on the Ingenuity database of molecules experimentally demonstrated or highly predicted to regulate Lox. This analysis identified miR-145 as a putative direct upstream Lox mRNA regulator (Fig. 4A; box).

Figure 4. miR145-dependent Lox gene expression by apoE.

(A) Upstream regulators of Lox showing differential gene expression after vascular injury as determined by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Green and red represent induction and repression, respectively. (B) Aortae from 6-mo old WT or apoE-null mice were harvested and analyzed by RT-qPCR for miR-145. Results show mean ± SE, n=4, p=0.0002 by 2-tailed t-test. (C) Serum-starved primary mouse VSMCs were incubated with 10% FBS in the absence (control; C) or presence of 2 μM apoE for 24 h. RNA was isolated and analyzed by RT-qPCR for miR-145. (D–E) VSMCs were transfected with pmiR-145 or anti-miR-145, serum starved for 48 h and stimulated with 10% FBS in the absence (control; C) or presence of 2 μM apoE3 for 24 h. RNA was isolated and analyzed by RT-qPCR for Lox, Col1a1, and FN. In C–E, results show mean ± SD of duplicate PCR reactions and are representative of at least three independent experiments. (F) Regulation of collagen-I, FN, and Lox gene expression by apoE through Cox2 and miR-145. See also Figure S4.

miR-145 levels were strongly reduced in apoE-null arteries as compared to wild-type (Fig. 4B), consistent with upregulation of Lox mRNA seen under the same conditions (refer to Fig. 1B). Moreover, apoE3 increased miR-145 in cultured VSMCs (Fig. 4C), consistent with the downregulation of Lox mRNA (refer to Fig. 2D). This inverse relationship between miR-145 and Lox mRNA is causal because ectopic miR-145 expression reduced Lox mRNA levels whereas an anti-miR-145 blocked the upregulation of Lox mRNA in response to apoE3 (Fig. 4D). Neither collagen-I nor FN mRNA levels were affected by ectopic expression or inhibition of miR-145 (Fig. 4E and SF4E). Thus, miR-145 induction selectively transduces the apoE3 signal to repress Lox mRNA. The combined effects of apoE3 on Cox2 and miR-145 account for its regulation of the collagen-I, FN, and Lox genes (Fig. 4F).

Inhibition of arterial stiffening reduces atherosclerosis

If suppression of ECM expression and arterial stiffening contribute to the cardiovascular protective effect of apoE, then a blockade of arterial stiffening should reduce atherosclerosis in apoE-null mice. ApoE-null mice on a high-fat diet were treated with the selective lysyl oxidase inhibitor, BAPN (Bruel et al., 1998; Kagan and Li, 2003; Tang et al., 1983). The lysyl oxidase family crosslinks collagen fibers and confers its tensile properties (Brasselet et al., 2005; Bruel et al., 1998; Wells, 2008). Lysyl oxidases also crosslink elastin, but several studies have shown that the net effect of BAPN treatment has been a reduction in tissue stiffness (Bruel et al., 1998). Blood pressure is not affected by BAPN (Berry et al., 1981; Iwatsuki et al., 1977; Kanematsu et al., 2010)

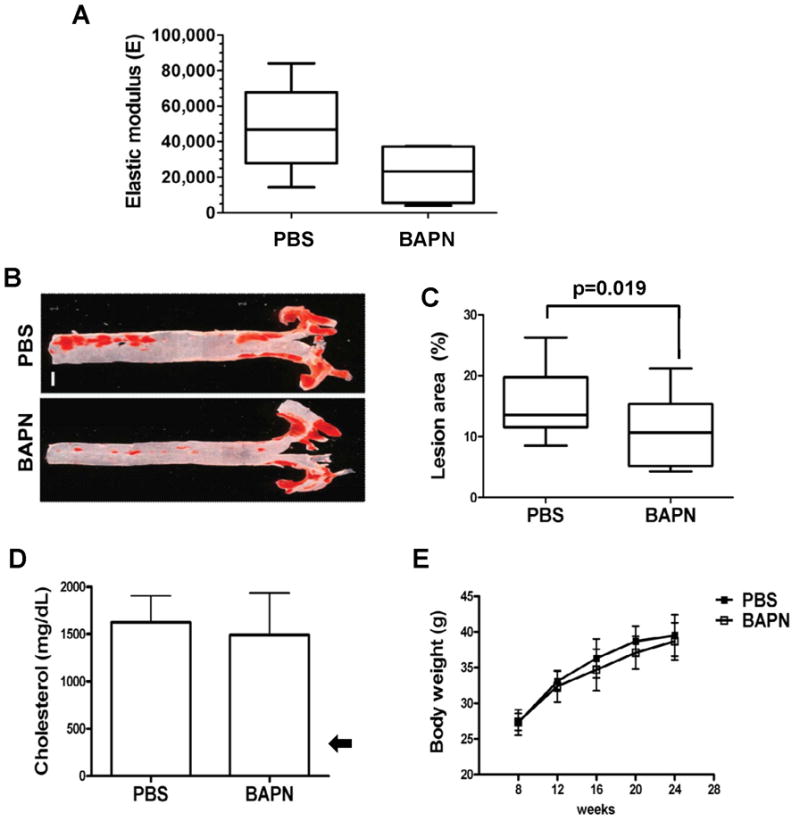

We treated apoE-null mice on a high-fat diet with vehicle or BAPN.. BAPN led to a notable reduction in arterial stiffness as compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 5A). BAPN also inhibited the development of atherosclerosis as determined by Oil Red O-staining of isolated aortae (Fig. 5B–C). Moreover, the degree to which lesion formation was reduced (~50%) agreed reasonably well with the degree to which BAPN reduced arterial stiffness (Fig. 5A). These inhibitory effects occurred despite the extraordinary high plasma cholesterol levels seen in apoE-null mice on a high-fat diet (Fig. 5D). Body weight was unaffected by BAPN (Fig. 5E). Thus, the inhibitory effect of apoE on arterial stiffness confers protection against atherosclerosis, and pharmacologic regulation of arterial biomechanics can attenuate disease even when plasma cholesterol remains extremely high.

Figure 5. Reduced atherosclerosis in apoE-null aortae softened in vivo with BAPN.

(A) AFM of aortae from ~2-mo old apoE-null mice fed a high-fat diet and treated with vehicle (PBS; n=5) or BAPN (n=4) for 16 weeks. Data are presented as a Tukey box and whisker plot with a 1-tailed Mann-Whitney test for softening by BAPN; p=0.032. (B–C) Oil red O staining and lesion quantification in aortae of apoE-null mice treated with PBS (n=17) or BAPN (n=15). Data are presented as Tukey box and whisker plots; p=0.019 by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test. Scale bar = 1 mm. (D) Plasma cholesterol levels (mean ± SD) in PBS (n=10) and BAPN (n=9) treated mice measured at the time of sacrifice. The arrow shows the cholesterol level in wild-type mice on a western diet (Nakashima et al., 1994). (E) Mice treated with PBS (n=17) or BAPN (n=17) from both groups were weighed every four weeks until sacrifice. p>0.05 by 2-way ANOVA. Results show mean ± SD.

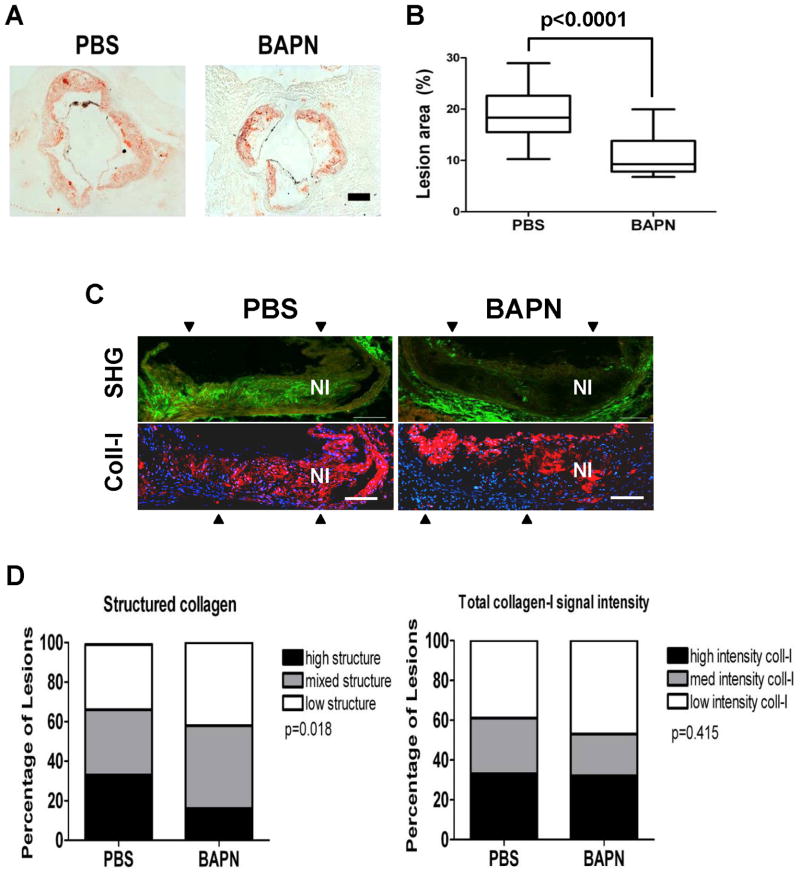

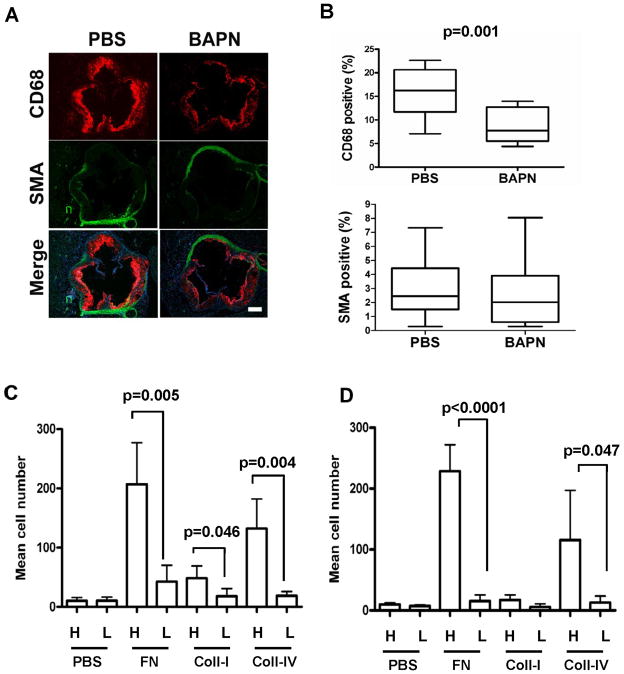

BAPN also reduced lesion area in aortic roots (Fig. 6A–B), and the magnitude of the effect was similar to what we observed in the thoracic aorta. We then analyzed the composition of these aortic root lesions. Second harmonic generation 2-photon microscopy revealed a clear reduction in highly structured collagen within the neointimas of lesions from the BAPN-treated mice (Fig. 6C; top panels and Fig. 6D; left) whereas total collagen-I levels were minimally affected (Fig. 6C; bottom panels and 6D; right). We observed chimeric staining patterns for α-smooth muscle actin (SMA; a marker of differentiated VSMCs) in lesions regardless of BAPN treatment (Fig. 7A–B). However, CD68-staining revealed that macrophage abundance in lesions was markedly reduced in the BAPN-treated mice (Fig. 7A–B). We then prepared ECM-coated hydrogels at the stiffness of healthy and diseased arteries to determine if the adhesion of THP-1 monocytes (Fig. 7C) or primary mouse thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages (Fig. 7D) was affected by substratum stiffness. Although the extent of cell adhesion depended on the subendothelial ECM protein used to prepare the hydrogel, in every case cell adhesion to ECM was strongly reduced when we softened the ECM from the high stiffness of lesions to the low stiffness of healthy arteries (Fig. 7C–D). Thus, the effect of BAPN on macrophage abundance in vivo can be phenocopied by direct manipulation of ECM stiffness in vitro. Collectively, these results reveal a specific aspect of atherogenesis affected by arterial stiffness and connect stromal ECM production and arterial stiffening to the inflammatory component of lesion development.

Figure 6. Reduced collagen structure and macrophage abundance in atherosclerotic lesions of BAPN-treated mice.

(A–B) Oil red O staining and lesion quantification in aortic roots of apoE-null mice treated with PBS (n=15) or BAPN (n=17). Data presented as Tukey box and whisker plots; p<0.0001 by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test. Scale bar = 200 μm. (C) Second harmonic generation detection of neointimal collagen. Top panels show composites of 3 serial second harmonic generation (SHG) images of an aortic root lesion from a PBS- or BAPN-treated mouse; collagen SHG signal and the elastin autofluorescence signal are pseudo-colored green and red, respectively. Bottom panels show composites of the same lesions stained for total collagen-I (red) and nuclei (Dapi; blue). Composite positions are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bar=100 μm. NI; neointima. (D) Double blind quantitation of lesion images from PBS (n=18) and BAPN (n=19) treated mice. Statistical significance was determined by Chi-square test.

Figure 7. Matrix stiffness regulates monocyte/macrophage adhesion to substratum.

(A) Aortic root lesions of apoE-null mice treated with PBS (n=15) or BAPN (n=16) were stained with markers for macrophages (anti-CD68; red) and VSMCs (anti-SMA; green). Scale bar=200 μm. (B) Quantification of aortic root sections stained positive for CD68 (p=0.001) and SMA (p=0.36). Data are presented as Tukey box and whisker plots. p values are from 2-tailed Mann-Whitney tests. (C) THP-1 monocytes or (D) primary murine thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophage were fluorescently labeled by incubation with calcein-AM and added to high-stiffness (H) or low-stiffness (L) ECM-coated hydrogels for 4 hr at 37 °C. The total numbers of Calcein-AM labeled cells were counted in 5 randomly selected fields. Results show mean ± SD; n=4. p values were determined by 2-tailed t-test.

Discussion

Our results identify apoE and apoE-containing HDL as negative regulators of ECM gene expression and arterial stiffening. This effect does not require the apoE lipid binding domain and confers cardiovascular protection independent of plasma cholesterol levels. We detected the suppressive effect of apoE on collagen-I, FN, and Lox expression selectively in de-differentiated VSMCs. This result suggests that apoE-HDL does not affect homeostatic arterial stiffness in contractile VSMCs, but rather acts when dedifferentiated VSMCs begin to synthesize ECM and stiffen their microenvironment during the onset of CVD.

Mechano-sensitive regulation of Cox2 and Lox expression opposed by apoE-HDL

Our initial transcript profiling results, as well similar results by others (Hui and Basford, 2005), suggested that apoE would be an overall inhibitor of ECM gene expression. However, a more detailed analysis of apoE action on deformable substrata indicate that apoE-HDL actually has a much more subtle role and that it selectively interferes with the increase in collagen-I, FN, and Lox gene expression that occurs in response to substratum stiffening (Fig. 4F). These results suggest the existence of a mechanically sensitive feed-forward loop which can accelerate ECM synthesis, matrix remodeling and arterial stiffening (Fig. 4F). By short-circuiting this loop, ApoE-HDL would restrain stiffening during the progression of atherosclerosis.

Cox2 regulates the production of PGI2 in VSMCs, and PGI2 inhibits collagen-I and FN gene expression. Moreover, Cox2 gene expression is mechanosensitive, with efficient expression seen only when VSMCs are on soft surfaces characteristic of normal arteries. We posit that the inverse relationship between ECM stiffness and Cox2 expression represses collagen-I/FN synthesis and contributes to healthy compliance in healthy vessels (Fig. 4F). Upon an atherogenic insult, however, the efficacy of this mechanism is reduced as dedifferentiated VSMCs accumulate and ECM production increases. ApoE-HDL helps to maintain negative feedback on collagen-I and FN synthesis by circumventing mechanical control of Cox2 gene expression (Fig. 4F). In apoE-null mice, and perhaps in humans with insufficient apoE-HDL, the stiffening-dependent loss of Cox2 would proceed unabated and exacerbate ECM synthesis, arterial stiffening and lesion development. Since Cox2 limits collagen-I expression, an increase in arterial stiffness may be a contributing factor to the cardiovascular hazards associated with chronic use of selective Cox2 inhibitors (FitzGerald, 2003).

ApoE also suppresses Lox expression in VSMCs. The effect of apoE on Lox is independent of Cox2 but strongly dependent on the upregulation of miR-145. It is not yet know if ApoE-HDL signaling to miR-145 and Cox2 involves distinct apoE receptors or divergent signaling downstream of a single receptor. The best studied apoE receptors are LDL receptor (LDLR), LRP, and heparin sulfate proteoglycan (Boucher et al., 2003; Nimpf and Schneider, 2000; Strickland et al., 2002). Our previous report indicated that Cox2 induction by apoE is likely independent of these receptors (Ali et al., 2008). Downregulation of miR-145 and its bicistronic partner, miR-143, have been implicated in the phenotypic switch of VSMCs from contractile (differentiated) to synthetic (de-differentiated) states (Boettger et al., 2009; Cordes et al., 2009). Consistent with these reports, we saw a large decrease in miR-145 at sites of vascular injury, a setting in which VSMC de-differentiation is occurring. However, apoE3 strongly increases miR-145 but does not affect smooth muscle differentiation as judged by our marker analysis. Thus, miR-145 downregulation may contribute to the de-differentiation of VSMCs, but its upregulation is insufficient for VSMC differentiation. The collective work of others (Boettger et al., 2009; Cordes et al., 2009; Xin et al., 2009) also suggest a complex and incompletely understood role for miR-145 in VSMC differentiation.

Implications for HDL biology

Many studies have concluded that HDL protects against cardiovascular disease, and pharmacological treatments and/or lifestyle changes that elevate HDL have become engrained into western medical practice. Canonically, HDL is thought to confer cardiovascular protection by stimulating reverse cholesterol transport, the movement of excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues back to the liver for excretion from the body (Mahley et al., 2006; Rothblat and Phillips, 2010). However, two major studies have recently questioned the importance of high HDL in cardiovascular protection. One clinical study, AIM-HIGH, increased HDL in response to slow-delivery niacin yet failed to show reduced cardiovascular risk (Nicholls, 2012; Nofer, 2012). Moreover, a large-scale mendelian randomization analysis found that increases in plasma HDL are not sufficient to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction (Voight et al., 2012). Our data may help to reconcile these conflicting reports because apoE-HDL is relatively rare, comprising only ~6% of the total HDL protein (Weisgraber and Mahley, 1980). Cardiovascular protective effects associated with elevated apoE-HDL may escape detection in clinical and population genetics analyses that rely on changes in total plasma HDL levels.

Arterial biomechanics and CVD

Atherosclerosis develops focally at sites of disturbed flow (Davies, 2009; Garcia-Cardena and Gimbrone, 2006; Gimbrone et al., 2000). In this context, we note that Cox2 production by endothelial cells is increased at sites of disturbed flow (Dai et al., 2004) and that PGI2 is an important Cox2 product of endothelial cells (Fitzgerald et al., 1987; Narumiya et al., 1999) as it is in VSMCs. Thus, disturbed flow should enhance PGI2 production focally which could then act in a paracrine manner to limit collagen-I and FN synthesis by proximal de-differentiated VSMCs. While this effect should be atheroprotective, the fact that lesions prefer to form at sites of disturbed flow indicates that reduced collagen and fibronectin expression are not sufficient to overcome other athero-stimulatory effects of disturbed flow. Nevertheless, our data do support the notion that loss of this effect (e.g. in apoE-null mice and perhaps humans with low apoE-HDL) likely contributes to arterial stiffening and lesion formation by reducing endothelial PGI2 production. Arterial stiffness in vivo is regulated by vascular tone as well as ECM composition, and PGI2 is a potent vasodilator (Fitzgerald et al., 1987; Narumiya et al., 1999). Tone and ECM composition may be linked through the Cox2-PGI2 pathway.

Monocyte/macrophage infiltration into the vessel wall contributes profoundly to atherosclerosis because subendothelial macrophages develop into the lipid-laden foam cells that populate lesions. Circulating monocytes adhere to intimal endothelial cells and begin the process of macrophage differentiation and transmigration into the subendothelial space. Our in vivo studies show that arterial stiffness is critical to this process. Arterial softening with BAPN strongly reduces macrophage abundance in lesions, and our hydrogel experiments show that ECM softening inhibits the adhesion of monocytes and macrophages to fibronectin and collagen-IV, components of the subendothelial ECM. Endothelial permeability is also sensitive to ECM stiffness (Huynh et al., 2011). These results raise the possibility that pharmacological control of arterial stiffness may complement the effect of cholesterol lowering drugs in treating CVD by regulating the inflammatory component of atherosclerosis. Although the extrapolation of results from mice to humans requires caution, our data fit well with epidemiologic studies identifying arterial stiffness as a cholesterol-independent risk factor for a first cardiovascular event (Duprez and Cohn, 2007; Mitchell et al., 2010).

Experimental Procedures

Expression profiling

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset GSE13865 was downloaded, processed, and analyzed using Partek Genomics Suite. The same software was used to determine differential gene expression in injured vs. uninjured arteries of SMA-GFP mice. Genes differentially expressed at sites of injury were then analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (www.ingenity.com). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Cell Culture

Primary explant murine VSMCs were isolated from 10–12 week male C57BL/6 (WT), IP-null, and conditional Cox2-expressing mice as described (Cuff et al., 2001). Near confluent monolayers were serum-starved for 48 h before stimulation with 10% FBS ± apolipoprotein, lipoprotein or cicaprost. Fibronectin-coated hydrogels were prepared with elastic moduli that approximate the stiffness of healthy or diseased arteries (Klein et al., 2009). Differentiated murine aortic VSMCs and thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were isolated similarly to described procedures (Golovina and Blaustein, 2006; Hodge-Dufour et al., 1997).

BAPN treatment of apoE-null mice

The effect of BAPN on atherosclerosis was determined using 8-week males fed a high-fat diet and given PBS or BAPN for 16 weeks. Aortae were isolated from the heart to the diaphragm, and a small portion of the thoracic aortae near the diaphragm was used to determine the elastic modulus. The remaining portions of aortae and the aortic roots were used to quantify atherosclerotic lesion formation by Oil-Red O staining. Sectioned aortic roots were also stained for CD68 and SMA. Blood was collected at the time of sacrifice for determination of total plasma cholesterol levels. See Supplemental Methods for further details.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

ApoE-HDL inhibits ECM expression and arterial stiffening

Substratum stiffening induces expression of collagen-I, fibronectin and lysyl oxidase

ApoE blocks stiffness-dependent collagen-I and fibronectin expression by regulating Cox2

Lysyl oxidase expression is negatively regulated by miR-145, and apoE reduces lysyl oxidase levels by increasing the expression of miR-145

The suppressive effect of apoE on arterial stiffness protects against atherosclerosis, and this effect is linked to a reduced abundance of lesional macrophages

Acknowledgments

We thank Liqun Yin and Xue Liang for assistance in the early stage of this work and Dr. Kathleen Propert for guidance in the biostatistical analysis of the in vivo data. We thank Garret FitzGerald, Sanai Sato, and Harvey Herschman for providing IP-null, SMA-GFP, and conditional Cox2-expressing mice, respectively. Bayer Schering Pharma AG kindly provided cicaprost. Supported by NIH grants HL66250, HL22633, HL56083, and HL093283.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali K, Lund-Katz S, Lawson J, Phillips MC, Rader DJ. Structure-function properties of the apoE-dependent COX-2 pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali ZA, Alp NJ, Lupton H, Arnold N, Bannister T, Hu Y, Mussa S, Wheatcroft M, Greaves DR, Gunn J, et al. Increased in-stent stenosis in ApoE knockout mice: insights from a novel mouse model of balloon angioplasty and stenting. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:833–840. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000257135.39571.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellien J, Thuillez C, Joannides R. Contribution of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors to the regulation of vascular tone in humans. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2008;22:363–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry CL, Greenwald SE, Menahem N. Effect of beta-aminopropionitrile on the static elastic properties and blood pressure of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Cardiovascular research. 1981;15:373–381. doi: 10.1093/cvr/15.7.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettger T, Beetz N, Kostin S, Schneider J, Kruger M, Hein L, Braun T. Acquisition of the contractile phenotype by murine arterial smooth muscle cells depends on the Mir143/145 gene cluster. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:2634–2647. doi: 10.1172/JCI38864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Border WA, Noble NA. Transforming growth factor beta in tissue fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1286–1292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher P, Gotthardt M, Li WP, Anderson RG, Herz J. LRP: role in vascular wall integrity and protection from atherosclerosis. Science. 2003;300:329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1082095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasselet C, Durand E, Addad F, Al Haj Zen A, Smeets MB, Laurent-Maquin D, Bouthors S, Bellon G, de Kleijn D, Godeau G, et al. Collagen and elastin cross-linking: a mechanism of constrictive remodeling after arterial injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2228–2233. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00410.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruel A, Ortoft G, Oxlund H. Inhibition of cross-links in collagen is associated with reduced stiffness of the aorta in young rats. Atherosclerosis. 1998;140:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes KR, Sheehy NT, White MP, Berry EC, Morton SU, Muth AN, Lee TH, Miano JM, Ivey KN, Srivastava D. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature. 2009;460:705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature08195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csiszar K. Lysyl oxidases: a novel multifunctional amine oxidase family. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;70:1–32. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(01)70012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuff CA, Kothapalli D, Azonobi I, Chun S, Zhang Y, Belkin R, Yeh C, Secreto A, Assoian RK, Rader DJ, et al. The adhesion receptor CD44 promotes atherosclerosis by mediating inflammatory cell recruitment and vascular cell activation. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1031–1040. doi: 10.1172/JCI12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai G, Kaazempur-Mofrad MR, Natarajan S, Zhang Y, Vaughn S, Blackman BR, Kamm RD, Garcia-Cardena G, Gimbrone MA., Jr Distinct endothelial phenotypes evoked by arterial waveforms derived from atherosclerosis-susceptible and -resistant regions of human vasculature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:14871–14876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406073101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PF. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:16–26. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez J. Arterial stiffness and extracellular matrix. Adv Cardiol. 2007;44:76–95. doi: 10.1159/000096722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005;310:1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprez DA, Cohn JN. Arterial stiffness as a risk factor for coronary atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2007;9:139–144. doi: 10.1007/s11883-007-0010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeblad M, Rasch MG, Weaver VM. Dynamic interplay between the collagen scaffold and tumor evolution. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2010;22:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald GA. COX-2 and beyond: Approaches to prostaglandin inhibition in human disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:879–890. doi: 10.1038/nrd1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald GA, Catella F, Oates JA. Eicosanoid biosynthesis in human cardiovascular disease. Hum Pathol. 1987;18:248–252. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cardena G, Gimbrone MA., Jr Biomechanical modulation of endothelial phenotype: implications for health and disease. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006:79–95. doi: 10.1007/3-540-36028-x_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimbrone MA, Jr, Topper JN, Nagel T, Anderson KR, Garcia-Cardena G. Endothelial dysfunction, hemodynamic forces, and atherogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;902:230–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06318.x. discussion 239–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovina VA, Blaustein MP. Preparation of primary cultured mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells for fluorescent imaging and physiological studies. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2681–2687. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge-Dufour J, Noble PW, Horton MR, Bao C, Wysoka M, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Trinchieri G, Puré E. Induction of IL-12 and chemokines by hyaluronan requires adhesion-dependent priming of resident but not elicited macrophages. The Journal of Immunology. 1997;159:2492–2500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui DY, Basford JE. Distinct signaling mechanisms for apoE inhibition of cell migration and proliferation. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh J, Nishimura N, Rana K, Peloquin JM, Califano JP, Montague CR, King MR, Schaffer CB, Reinhart-King CA. Age-related intimal stiffening enhances endothelial permeability and leukocyte transmigration. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:112ra122. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishigami M, Swertfeger DK, Granholm NA, Hui DY. Apolipoprotein E inhibits platelet-derived growth factor-induced vascular smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation by suppressing signal transduction and preventing cell entry to G1 phase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20156–20161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishigami M, Swertfeger DK, Hui MS, Granholm NA, Hui DY. Apolipoprotein E inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation but not the inhibition of migration is mediated through activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1020–1026. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.4.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki K, Cardinale GJ, Spector S, Udenfriend S. Reduction of blood pressure and vascular collagen in hypertensive rats by beta-aminopropionitrile. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1977;74:360–362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.1.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadler KE, Hill A, Canty-Laird EG. Collagen fibrillogenesis: fibronectin, integrins, and minor collagens as organizers and nucleators. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan HM, Li W. Lysyl oxidase: properties, specificity, and biological roles inside and outside of the cell. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:660–672. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanematsu Y, Kanematsu M, Kurihara C, Tsou TL, Nuki Y, Liang EI, Makino H, Hashimoto T. Pharmacologically induced thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. Hypertension. 2010;55:1267–1274. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima K, Marchadier DH, Miller GC, Gao GP, Wilson JM, Rader DJ. Complete prevention of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice by hepatic human apoE gene transfer with adeno-associated virus serotypes 7 and 8. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1852–1857. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000231520.26490.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein EA, Yin L, Kothapalli D, Castagnino P, Byfield FJ, Xu T, Levental I, Hawthorne E, Janmey PA, Assoian RK. Cell-cycle control by physiological matrix elasticity and in vivo tissue stiffening. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1511–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothapalli D, Fuki I, Ali K, Stewart SA, Zhao L, Yahil R, Kwiatkowski D, Hawthorne EA, FitzGerald GA, Phillips MC, et al. Antimitogenic effects of HDL and APOE mediated by Cox-2-dependent IP activation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:609–618. doi: 10.1172/JCI19097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothapalli D, Zhao L, Hawthorne EA, Cheng Y, Lee E, Pure E, Assoian RK. Hyaluronan and CD44 antagonize mitogen-dependent cyclin D1 expression in mesenchymal cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:535–544. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta EG. Central arterial aging and the epidemic of systolic hypertension and atherosclerosis. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2007;1:302–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SF, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Mih JD, Shea BS, Kho AT, Sharif AS, Tager AM, Tschumperlin DJ. Feedback amplification of fibrosis through matrix stiffening and COX-2 suppression. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:693–706. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahley RW, Huang Y, Weisgraber KH. Putting cholesterol in its place: apoE and reverse cholesterol transport. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1226–1229. doi: 10.1172/JCI28632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter CM, Ma L, von Lukowicz T, Meier P, Lohmann C, Zhang D, Kilic U, Hofmann E, Ha SW, Hersberger M, et al. Increased balloon-induced inflammation, proliferation, and neointima formation in apolipoprotein E (ApoE) knockout mice. Stroke. 2006;37:2625–2632. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000241068.50156.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GF, Hwang SJ, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Pencina MJ, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Levy D, Benjamin EJ. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;121:505–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.886655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narumiya S, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F. Prostanoid receptors: structures, properties, and functions. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1193–1226. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls SJ. The AIM-HIGH (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome With Low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcomes) Trial: To Believe or Not to Believe? Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;59:2065–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimpf J, Schneider WJ. From cholesterol transport to signal transduction: low density lipoprotein receptor, very low density lipoprotein receptor, and apolipoprotein E receptor-2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1529:287–298. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nofer JR. Hyperlipidaemia and cardiovascular disease: HDL, inflammation and surprising results of AIM-HIGH study. Current opinion in lipidology. 2012;23:260–262. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328353c4e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oga T, Matsuoka T, Yao C, Nonomura K, Kitaoka S, Sakata D, Kita Y, Tanizawa K, Taguchi Y, Chin K, et al. Prostaglandin F(2alpha) receptor signaling facilitates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis independently of transforming growth factor-beta. Nat Med. 2009;15:1426–1430. doi: 10.1038/nm.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedrahita JA, Zhang SH, Hagaman JR, Oliver PM, Maeda N. Generation of mice carrying a mutant apolipoprotein E gene inactivated by gene targeting in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4471–4475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plump AS, Smith JD, Hayek T, Aalto-Setala K, Walsh A, Verstuyft JG, Rubin EM, Breslow JL. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell. 1992;71:343–353. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90362-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothblat GH, Phillips MC. High-density lipoprotein heterogeneity and function in reverse cholesterol transport. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:229–238. doi: 10.1097/mol.0b013e328338472d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MA, DeSimone DW. Cell adhesion receptors in mechanotransduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehouwer CD, Henry RM, Ferreira I. Arterial stiffness in diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: a pathway to cardiovascular disease. Diabetologia. 2008;51:527–539. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0918-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland DK, Gonias SL, Argraves WS. Diverse roles for the LDL receptor family. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:66–74. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swertfeger DK, Hui DY. Apolipoprotein E receptor binding versus heparan sulfate proteoglycan binding in its regulation of smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25043–25048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symmons DP, Barrett EM, Bankhead CR, Scott DG, Silman AJ. The incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United Kingdom: results from the Norfolk Arthritis Register. 1994;33:735–739. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.8.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SS, Trackman PC, Kagan HM. Reaction of aortic lysyl oxidase with beta-aminopropionitrile. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:4331–4338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorngate FE, Yancey PG, Kellner-Weibel G, Rudel LL, Rothblat GH, Williams DL. Testing the role of apoA-I, HDL, and cholesterol efflux in the atheroprotective action of low-level apoE expression. Journal of lipid research. 2003;44:2331–2338. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300224-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyberg J, Blomgren K, Roy J, Tran PK, Hedin U. Phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells after arterial injury is associated with changes in the distribution of laminin and fibronectin. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:837–846. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyberg J, Hedin U, Sjolund M, Palmberg L, Bottger BA. Regulation of differentiated properties and proliferation of arterial smooth muscle cells. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:966–990. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.6.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, Frikke-Schmidt R, Barbalic M, Jensen MK, Hindy G, Holm H, Ding EL, Johnson T, et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisgraber KH. Apolipoprotein E: structure-function relationships. Adv Protein Chem. 1994;45:249–302. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60642-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW. Subfractionation of human high density lipoproteins by heparin-Sepharose affinity chromatography. J Lipid Res. 1980;21:316–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells RG. The role of matrix stiffness in regulating cell behavior. Hepatology. 2008;47:1394–1400. doi: 10.1002/hep.22193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin M, Small EM, Sutherland LB, Qi X, McAnally J, Plato CF, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. MicroRNAs miR-143 and miR-145 modulate cytoskeletal dynamics and responsiveness of smooth muscle cells to injury. Genes & development. 2009;23:2166–2178. doi: 10.1101/gad.1842409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota T, Kawakami Y, Nagai Y, Ma JX, Tsai JY, Kincade PW, Sato S. Bone marrow lacks a transplantable progenitor for smooth muscle type alpha-actin-expressing cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:13–22. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.