Abstract

Spine stabilisation exercises, in which patients are taught to preferentially activate the transversus abdominus (TrA) during “abdominal hollowing” (AH), are a popular treatment for chronic low back pain (cLBP). The present study investigated whether performance during AH differed between cLBP patients and controls to an extent that would render it useful diagnostic tool. 50 patients with cLBP (46.3 ± 12.5 years) and 50 healthy controls (43.6 ± 12.7 years) participated in this case–control study. They performed AH in hook-lying. Using M-mode ultrasound, thicknesses of TrA, and obliquus internus and externus were determined at rest and during 5 s AH (5 measures each body side). The TrA contraction-ratio (TrA-CR) (TrA contracted/rest) and the ability to sustain the contraction [standard deviation (SD) of TrA thickness during the stable phase of the hold] were investigated. There were no significant group differences for the absolute muscle thicknesses at rest or during AH, or for the SD of TrA thickness. There was a small but significant difference between the groups for TrA-CR: cLBP 1.35 ± 0.14, controls 1.44 ± 0.24 (p < 0.05). However, Receiver Operator Characteristics (ROC) analysis revealed a poor and non-significant ability of TrA-CR to discriminate between cLBP patients and controls on an individual basis (ROC area under the curve, 0.60 [95% CI 0.495; 0.695], p = 0.08). In the patient group, TrA-CR showed a low but significant correlation with Roland Morris score (Spearman Rho = 0.328; p = 0.02). In conclusion, the difference in group mean values for TrA-CR was small and of uncertain clinical relevance. Moreover, TrA-CR showed a poor ability to discriminate between control and cLBP subjects on an individual basis. We conclude that the TrA-CR during abdominal hollowing does not distinguish well between patients with chronic low back pain and healthy controls.

Keywords: Abdominal hollowing, Ultrasound, Transversus abdominis muscle, Chronic low back pain

Introduction

In contemporary physiotherapy, spinal segmental stability exercises are a popular treatment in the rehabilitation of chronic low back pain (cLBP). Several systematic reviews have shown that this type of exercise represents an effective treatment approach, although it is not necessarily superior to other physiotherapeutic interventions [11, 23, 34].

The rationale behind the treatment concept is that the segmental stability of the lumbar spine is controlled by deep-lying muscles, such as multifidi and transversus abdominis (TrA) that have an anatomical connection to the lumbar spine [43]. The relationship between anatomical structure and function has been described by Panjabi [32]: stability in a lumbar segment requires a coordinated interaction between the passive subsystem (osteoligamentous structures), the active subsystem (muscles) and the neural subsystem (central and peripheral nervous systems controlling the muscles). The muscles involved are either part of the global muscle system (large torque-producing muscles) providing general trunk stabilisation, or part of the local muscle system (small muscles directly attached to the lumbar vertebrae) responsible for providing segmental stability [2]. The importance of TrA in trunk stabilisation is further supported by the experimental investigations of Hodges et al. [16, 18, 19], in which it was shown that the motor control function of this muscle was altered in LBP patients.

“Abdominal hollowing” (AH) exercises are purported to assist in restoring motor control in LBP patients by retraining the voluntary activation of TrA, using selective low-level tonic contractions. Success in performing the exercises is given by the ability to activate TrA in preference to the more superficial abdominal muscles, obliquus internus (OI) and obliquus externus (OE) and/or rectus abdominus [1, 35, 41]. The ability to sustain the preferential TrA contraction represents an additional therapeutic aim: patients should ideally be able to hold the TrA contraction for 10 s during each of 10 repetitions in prone lying or four-point kneeling before progressing to more functional positions [36]. However, to date, mastery of this particular aspect of TrA function in patients with cLBP has rarely been examined.

AH is not only an exercise training modality; it is also used as a performance test, in which success is measured by appropriate pressure changes in a pressure biofeedback device (an air-filled reservoir) placed under the abdomen in prone lying [36] or by the degree of TrA muscle thickness change recorded on ultrasound [4, 7, 10, 12, 14, 20, 22, 40]. Using the biofeedback unit, two studies have reported significant differences in abdominal function between back-healthy controls and patients with chronic LBP [16] or “lumbar symptomatic” patients attending physiotherapy [6]. However, the use of the pressure biofeedback unit (PBU) as an assessment instrument has been questioned, since the measures obtained give only an indirect indication of TrA function and have shown poor reliability both between assessment days [39] and between raters [44]. At low levels of contraction, the extent of TrA thickening measured using ultrasound is reported to be a valid method of assessment compared with either fine wire electromyographic (EMG) measures of TrA activity [17, 27] or MRI indices of muscle thickness [15]. Two groups have used ultrasound to compare abdominal muscle thickness changes of healthy controls and patients with cLBP during AH: Gorbet et al. [12] found no significant difference between the groups in their ability to activate TrA, whereas Critchley and Coutts [7] showed a significantly reduced ability in the patient group compared with controls. However, they did not report the corresponding diagnostic accuracy of the test for predicting group membership on an individual basis.

A number of studies have documented good reliability for static measures of resting abdominal muscle thickness [5, 7, 29] [17, 25]. The use of indices expressing the thickness ratio of the relaxed and contracted TrA has further contributed to the quantification of TrA function [41], and such indices have been shown to yield reliable between-day measures in both control subjects and in patients with cLBP [25]. To measure muscle dimensions, bright (B)-Mode ultrasound is usually used, with muscle thickness being measured using on-screen callipers [7, 21, 22, 29, 41, 42]. However, by applying moving (M)-Mode ultrasound, a depth versus time chart can be displayed, permitting the measurement of thickness changes over time [5]. This allows investigation of the ability to sustain the TrA contraction and to examine whether this aspect of function shows any impairment in patients with cLBP.

The aim of the present study was to use M-mode ultrasound to investigate whether the extent of TrA thickness change and the variability in TrA thickness during performance of AH differed between healthy controls and patients with cLBP to an extent that would render these measures useful diagnostic tools.

Methods

Subjects/patients

The patients were recruited from the local University Hospitals as well as through an advertisement in the local newspaper. The healthy controls were recruited through the same advertisement as the patients and flyers placed in the local universities and by invitation amongst friends and colleagues. 135 subjects were pre-screened during a telephone interview in an attempt to match 50 of them to the collective of 50 LBP patients with respect to gender, age (±10 years), body height (±10 cm) and weight (±10 kg).

The control subjects had to have been LBP-free for at least the past year and have had no history of LBP requiring a visit to the doctor or time off work. The inclusion criteria for the patient group were persistent LBP with or without referred pain (of a non-radicular nature) for at least 3 months, serious enough to cause absence from work or solicit medical attention; average pain intensity over the past 2 weeks ≥3 and ≤8 on a 0–10 graphic rating scale and willingness to comply with the study protocol. Exclusion criteria included constant or persistent severe pain (>8/10); non-mechanical LBP; neurological symptoms; severe spinal instability (spondylolisthesis grade 3 or higher); osteoporosis (height loss of ≥4 cm since the age of 20); structural deformity (rigid scoliosis in clinical examination, flexion movements); systemic inflammatory disease; unstable metabolic disease or any other corresponding disorders preventing active rehabilitation; previous spinal fusion; severe cardiovascular disease (NYHA III and IV); acute infection; recent (in the last 3 months) major abdominal surgery; lack of co-operation; uncontrolled alcohol or drug abuse and unstable psychopathological diseases. A further exclusion criterion for both groups was pregnancy (or pregnancy within the past 2 years). The study was approved by the local medical ethics committee. All suitable participants received verbal and written information about the test procedure and gave their signed informed consent to participate.

Prior to the ultrasound assessment, subjects completed a short questionnaire comprising questions on demographics. In addition, those with cLBP completed questions on general health, pain (0–10 graphic rating scale for pain in the last week, on average and at worst) and disability due to low back pain (Roland Morris disability questionnaire [9, 37]).

Measurements

Prior to testing, subjects received instructions on how to perform AH contractions. Emphasis was given to slowly and gently bringing the belly button in towards the spine, thereby hollowing the abdomen, and to hold this stable while continuing to breathe normally. The exercises were performed in a comfortable supine position; for further details of the specific test procedure see Mannion et al. [25]. For the ultrasound recordings a Philips HDI 5000 with a linear array transducer (L12-5 MHz, 38 mm, SN 01NPTV, Philips Medical Systems, Zürich, Switzerland) with an additional TDI application was used. A custom-made high-density foam enforced belt was used to ensure accurate and hands-off application of the ultrasound transducer. To ensure good signal transmission, a 130 × 120 × 10 mm gel stand-off pad (Sonar-Aid, Alloga AG, Burgdorf, Switzerland) and transmission gel were placed between the transducer head and skin. The transducer was positioned under ultrasound guidance in B (brightness)-mode, midway between the costal margin and the iliac crest along the anterior axillary line and finally adjusted to ensure that, at rest, the fascial borders of the three muscles (TA, OI and OE muscles) appeared parallel on the screen.

After this, five AH exercises were performed on each body side (starting with the right or left side at random). During the actual measurement trials, the subjects were not allowed to see the ultrasound images and they received no verbal feedback.

Data processing

All analyses were made off-line, with the investigators blind to the subject’s group-membership. The leading edge points (i.e., on the upper border) of the fascia of the OE, OI and TrA, and the lower fascia of the TrA muscle were marked as manually selected control points at regular intervals throughout the M-mode image (white dotted bars in Fig. 1). A custom-written plug-in of the HDI-Lab software (version 1.9 ATL/Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA, USA) was then used to automatically track the borders between adjacent control points, relying on the TDI velocity information to derive the displacement of a given point between two adjacent M-mode columns (displacement being equal to tissue velocity multiplied by the time difference between adjacent M-mode columns) [25]. The distance between the top and bottom fascial lines for each M-mode column gave a measure of the thickness of the muscle over time, and this was saved as text data.

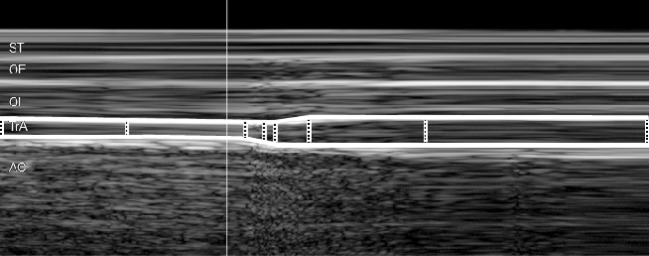

Fig. 1.

M-mode ultrasound image of the abdominal hollowing manoeuvre. The distances between fascial borders were derived by means of a semi-automatic approach, based on manually selected control points (white dotted vertical bars) plus tissue Doppler velocity information to track the borders between adjacent control points (shown here for TrA, transversus abdominis, as thick white lines bordering the muscle). Note: for clarity, all markings are shown with thicker line-widths than those used for the actual analysis process. No time or depth scales were displayed on the M-mode image during digitization; however, the image represents approximately 4 s worth of data (x-axis) (~1.5 s of rest and ~2.5 s of abdominal hollowing) with a total scan depth of ~37 mm (y-axis). ST subcutaneous tissue; OE obliquus externus; OI obliquus internus; AC abdominal contents

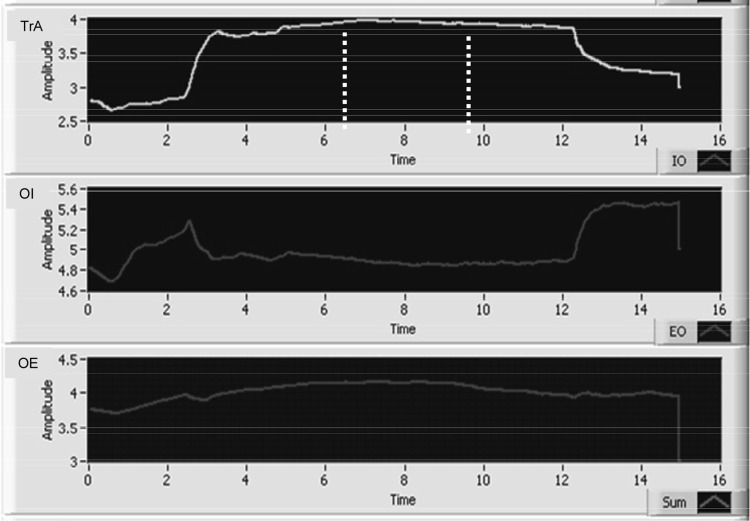

The text data were imported into a custom-written LabView software programme to determine the resting thickness of TrA, OI and OE (given by the 1 s value during quiet rest, just before the test contraction began) and the maximal thickness of TrA over any given 3-s period during the voluntary contraction (area between the dotted vertical bars; Fig. 2). The thicknesses of OI and OE at the point of maximum TA thickness were selected automatically and the appropriateness of the selected area was confirmed by visual inspection.

Fig. 2.

Muscle thickness, given by the difference in depth of the upper and lower fascial borders of the transversus abdominis (TrA), obliquus internus (OI) and obliquus externus muscle (OE). The maximal thickness of TrA over any given 3 s period during the voluntary contraction was automatically determined (see dotted vertical bars)

From the above data, the following indices were determined, as previously described by Teyhen et al. [41]:

TrA contraction ratio = TrA thickness contracted/TrA thickness at rest

OE + OI contraction ratio = OE + OI thickness contracted/OE + OI thickness at rest

TrA preferential activation ratio (difference in the TrA proportion of the total lateral abdominal muscle thickness in going from the relaxed to the contracted state) = (TrA contracted/TrA + OE + OI contracted) − (TrA at rest/TrA +OE + OI at rest)

To examine the ability of the subject to sustain the TrA contraction, the standard deviation of the mean muscle thickness recorded over each 3-s maximal contraction period was determined.

Data analysis/statistics

Continuous data are presented as means with standard deviations (SD) or 95% confidence intervals (CI), and categorical data, as frequencies. Differences between group mean values for continuous variables were examined with independent Student t-test; Chi-square contingency tests were used to examine group differences in categorical variables.

The primary dependent variable of interest was the TrA contraction ratio, since this has been shown to be a relevant measure that can be reliably measured [12, 25, 41]. To capitalise on the repeated measurements taken per subject and body side (median value of 10 trials per subject, in total), linear mixed effects models (LMM) were used to describe the association between TrA contraction ratio and its potential predictors (group membership plus other possible confounders). Group membership (controls/cLBP patient) was treated as a random factor for which individual intercepts were fitted. Furthermore, individual intercepts were fitted for the random factor body side, which was treated as nested within “subject”. Log-transformation of the TrA contraction ratio data was necessary to fulfil the assumptions of normal distribution of residuals [3]. After model fitting, the residuals and leverages were inspected for violations of model assumptions using potential-residual plots. Estimates of the higher posterior density (HPD) lower and upper boundaries of the 95% CI and the p values of the hypothesis tests (which indicate whether the corresponding coefficient estimates are significantly different from 0) were calculated with 100,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo samples. First, a simple model was built with group membership (cLBP, control) as the only explanatory variable (this corresponds to the linear model underlying the t-test results shown for group mean differences). Second, an extended model was built with the additional and potentially confounding explanatory variables sex (male vs. female), age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), incontinence, sport. This model results in an estimate of the coefficient for “group membership”, which is adjusted for the additionally included variables. Noting that the simple model is nested in the adjusted model, goodness-of-fit of the two models was compared with a likelihood-ratio test and the two information criteria, Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

The diagnostic performance of the TrA contraction ratio (i.e., its ability to discriminate between groups) was examined using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. The relationship between TrA-ratios and Roland Morris disability scores was examined using Spearman rank correlation analysis. For these two analyses, the ten repeated muscle thickness measures for a given person were averaged.

Power calculations (MedCalc Statistical Software, Mariakerke, Belgium) revealed that, with a minimum of at least 41 patients in each group, the probability was 80% that the TrA contraction ratio would be able to discriminate between the groups with a two-sided 5.0 per cent significance level, if the true area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.75 (fair-good accuracy in discrimination).

The statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical package SPSS version 17.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago IL, USA) and R (R Development Core Team 2008, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was accepted at the 5% level. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

Results

Group demographics and characteristics of the two groups

The demographic and personal characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between them for gender distribution, age, height, weight, side-dominance, medical history of abdominal or gynaecological surgery, prior familiarity with segmental stability exercises or work posture (sitting/standing vs. moving around). In contrast, there were statistically significantly differences (p < 0.05) for BMI, urinary incontinence and their participation in sport (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and personal characteristics of the cLBP patients and control subjects

| Variable | cLBP patients (N = 50) | Controls (N = 50) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (men/women) | 18/32 | 18/32 | – |

| Age (years) | 46.3 (12.5) | 43.4 (13.0) | 0.252 |

| Height (m) | 1.69 (0.08) | 1.71 (0.10) | 0.144 |

| Weight (kg) | 73.8 (12.4) | 70.5 (13.9) | 0.218 |

| Body mass index (BMI) (kg m−2) | 26.0 (4.5) | 24.0 (4.3) | 0.028 |

| Side dominance (right/left/no dominance) | 45/2/3 | 45/4/3 | 0.700 |

| Reported incontinence (no/yes) | 36/14 | 45/5 | 0.022 |

| Previous abdominal or gynaecological surgery (no/yes/missing) | 28/17/5 | 32/18/0 | 0.953 |

| Familiar with segmental stability exercises prior to testing (no/yes) | 47/3 | 45/5 | 0.461 |

| Work situation (sitting or standing/moving around) | 26/24 | 29/21 | 0.546 |

| Regular participation in sport (yes/no) | 31/19 | 41/9 | 0.026 |

Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated

Pain and disability levels in the cLBP group

The median values for pain intensity in the cLBP patients were, for average pain, 5 (interquartile range (IQR), 4–6), and for maximal pain, 7 (IQR, 5–8); the median Roland Morris disability score was 9 (IQR, 5–12) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean (SD) abdominal muscle thicknesses at rest and during abdominal hollowing, SD of mean thicknesses during sustained contraction, and contraction/activation ratios for cLBP patients and control subjects

| Muscle and condition | cLBP (N = 50) | Controls (N = 50) |

|---|---|---|

| TrA rest | 4.1 (0.9) | 3.8 (1.0) |

| TrA max | 5.4 (1.0) | 5.3 (1.1) |

| TrA SD of max | 0.075 (0.052) | 0.076 (0.047) |

| OI rest | 7.2 (1.9) | 7.5 (2.3) |

| OI max | 7.7 (2.0) | 8.1 (2.6) |

| OI SD of max | 0.098 (0.091) | 0.108 (0.092) |

| OE rest | 6.2 (1.6) | 6.5 (2.9) |

| OE max | 6.1 (1.6) | 6.3 (2.8) |

| OE SD of max | 0.070 (0.060) | 0.071 (0.046) |

| TrA contraction ratio | 1.35 (0.14) | 1.44 (0.24)* |

| OE + OI contraction ratio | 1.03 (0.04) | 1.04 (0.06) |

| TrA pref activation ratio | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.03) |

For definitions of indexes, see text

TrA transversus abdominis, OE obliquus externus, OI obliquus internus

* p = 0.03; otherwise, there were no significant differences between the groups for any of the above variables (p > 0.12 in each case)

Absolute muscle thicknesses and contraction ratios

There were no significant differences (p > 0.05) between the groups for any of the absolute abdominal muscle thicknesses at rest or during AH (Table 2). Similarly, there were no significant group differences (p > 0.05) in the ability to sustain the contraction, as given by the SDs of the mean thickness values measured during hollowing (Table 2). The group mean TrA contraction ratio was slightly but significantly higher in the control group (for more detailed analysis, see below), but neither of the other contraction ratio variables showed any significant group differences (Table 2).

Tables 3 and 4 show the results of the fixed effects of the simple and adjusted LMM, respectively. The simple model indicated that the cLBP patients had a significantly lower log(TrA ratio) compared with the healthy subjects (p = 0.005; Table 3). However, adjustment for seven additional variables in the extended model reduced this effect to a trend (p = 0.098; Table 4). With the exception of age, which was positively associated with log(TrA ratio) in a marginally significant way, the other variables did not have coefficient estimates significantly different from 0 (Table 4). The likelihood ratio test comparing the goodness-of-fit of the two models, and the lower AIC and BIC values, clearly favoured the extended model (Table 5).

Table 3.

The estimated regression coefficients for the simple model with “group membership” as single explanatory variable incorporated

| Estimate | 95% HPD CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.342 | 0.32; 0.37 | <0.001 |

| Group (cLBP vs. control) | −0.051 | −0.09; −0.02 | 0.005 |

The estimate for group membership shows how much the log(TrA ratio) is expected to differ on average between patients with cLBP and healthy controls

Table 4.

Estimated regression coefficients for the extended model adjusted for possible confounding variables

| Estimate | 95% HPD CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.176 | −2.01; 2.30 | 0.950 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.039 | −0.01; 0.09 | 0.117 |

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.016 | −0.00; 0.03 | 0.065 |

| Weight (per 10 kg) | −0.037 | −0.19; 0.10 | 0.550 |

| Height (per 10 cm) | 0.023 | −0.10; 0.16 | 0.648 |

| BMI (per 10 units) | −0.026 | −0.41; 0.40 | 0.967 |

| Incontinence (yes vs. no) | 0.003 | −0.05; 0.06 | 0.903 |

| Sport (yes vs. no) | 0.015 | −0.03; 0.05 | 0.495 |

| Group (cLBP vs. control) | −0.030 | −0.07; −0.01 | 0.098 |

The estimates show how much the log(TrA ratio) is expected to change if a factor is increased by 1 unit. Example: an increase in weight of 10 kg corresponds to a decrease in the log(TrA ratio) of −0.037

Table 5.

The likelihood ratio test for the simple versus the extended model

| d.f. | AIC | BIC | Log-likelihood | χ2 | d.f. | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple model | 5 | −1,163.00 | −1,138.57 | 586.50 | |||

| Extended model | 12 | −1,171.02 | −1,112.37 | 597.51 | 22.019 | 7 | 0.0025 |

The AIC and BIC as well as the χ2 test show that the adjusted model fits the data better than the simple unadjusted model (see text for further details and definitions of abbreviations)

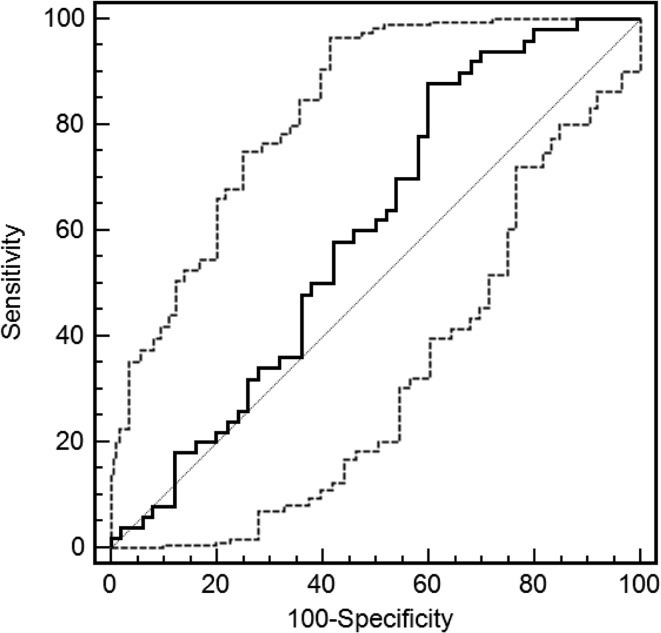

ROC curve for distinguishing between groups based on TrA contraction ratio

The AUC was 0.60 [CI 0.50–0.70] (SE 0.056) and just failed to reach significance (p = 0.07; Fig. 3), indicating that the TrA contraction ratio was not able to classify individuals into their respective groups (healthy control or cLBP patient) any better than could be done by chance alone (=an AUC of 0.50; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve for the mean TrA contraction ratio (mean of all trials, both body sides). The ROC area under the curve = 0.598 (SE 0.057) [95% CI 0.495; 0.695], p = 0.08). The solid line indicates the ROC curve (and 95% CI) and the dotted line joining the points at 0,0 and 100,100 represents the 0.5 reference line

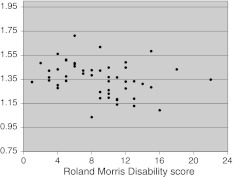

Relationship between TrA contraction ratio and Roland Morris disability score

There was a low but significant negative correlation between the Roland Morris disability scores and the TrA contraction ratio scores (Rho = −0.328; p = 0.02; Fig. 4): the greater the self-rated disability the lower the TrA contraction ratio.

Fig. 4.

The association between the Roland Morris disability questionnaire score and the mean TrA contraction ratio for all trials (both body sides) of each patient

Discussion

The main aim of the present study was to use M-mode ultrasound to investigate whether the degree of TrA thickness change during performance of AH exercises differed between healthy controls and patients with cLBP, to an extent that would render it a useful diagnostic tool. Whilst a significant difference in group mean values for TrA contraction ratio was observed, it was small and of uncertain clinical relevance, and the index showed very poor ability to discriminate between control subjects and those with cLBP on an individual basis.

To allow a valid comparison of TrA function between the groups [26], special attention was paid to ensuring that the anthropometric characteristics of the patients and the healthy controls were well matched. However, during subject recruitment it proved to be challenging to find matching controls with correspondingly high body weights and BMI. Hence, regardless of the satisfactory matching for body height and weight the patient group still had a slightly but significantly greater mean BMI than the control group. Higher BMI is typical of cLBP populations [13, 24] and together with the other between-group differences in involvement in sport, might have reflected a more sedentary lifestyle in the patient group than the controls. Since matching was not able to fully ensure group comparability, a multivariable model was used to investigate the effect of group membership whilst accounting for potential confounders.

Similar to previous findings, incontinence problems were also more frequent in the cLBP group than in the control group [8]. Although a synergistic response between abdominal and pelvic floor muscles has been reported [30, 38], there was no clear association between diminished AH performance and incontinence in the present study. Indeed, in our linear mixed effect model analysis this factor did not contribute significantly to explaining individual differences in TrA contraction ratio.

To ensure that the abdominal muscle performance of the subjects was not influenced by their lack of understanding of the AH exercise, all subjects received a short exercise instruction and were given the opportunity to practice with real-time ultrasound feedback before the actual measurements were made. Using ultrasound as a feedback instrument has been reported to decrease the number of practice trials required for correct performance of AH [14]. Hence, it was considered to be a means of ensuring good instruction and simultaneously preventing unnecessary fatigue. In similar investigations, Critchley et al. [7], Gorbet et al. [12] and Kiesel et al. [21] reported slightly larger TrA-contraction ratios of 1.50, 1.52 and 1.48, respectively, for their healthy subjects compared with the value of 1.43 for the controls in the present study. In all of these previous investigations, measurements were performed using B-mode rather than M-mode ultrasound. However, McMeeken et al. [27] reported no significant difference in TrA thickness measures related to the use of different transducers or modes of ultrasound under resting conditions, and hence this is unlikely to explain the differences. A more likely source for the differing values might be the different approaches used to make the thickness measures. In the present investigation the highest mean value over any given 3-s period was considered as “the maximum”, to avoid any transient peaks given by the instantaneous maximum and on the basis that we would also gain information on the ability to steadily sustain the contraction. The highest value over a 3-s contraction would per se be expected to yield slightly lower maximum values than the maximum instantaneous thickness.

Based on the theory underlying the prescription of the exercises [35] and on the encouraging reports from other similar investigations [7, 10, 16] we expected to find a larger between-group difference concerning TrA function measured by ultrasound. From our preliminary investigations [33], we did not expect to find TrA-dysfunction in all cLBP subjects, but the results obtained were still rather unexpected. The group difference in TrA-ratio, though statistically significant, proved to be relatively small and was reduced to a non-significant trend when confounding variables were also considered. In the present study the patients achieved a TrA contraction ration of 1.35, compared with a value of 1.19 in the study of Critchley and Coutts [7] (with mean values for the control groups being 1.43 and 1.50, respectively, in the two studies). Factors such as different initial positions during the measurement (supine hook lying (present study) vs. 4-point kneeling) [7], or (unknown) differences in the practice or instructions given to participants might have contributed to the differences between the studies, although it is difficult to explain why any such differences in methodology would have elicited a greater effect on the performance in the patients than in the controls. In one study, a strong linear correlation was reported between the thickness changes of TrA measured by ultrasound and the corresponding TrA EMG activity as a per cent of maximum up to 100% EMG activity, indicating that it was a valid and sensitive measure of muscle activity [27]. In contrast, in a small study of three healthy males, Hodges et al. [17] showed that thickness measures made using ultrasound accurately reflect the intensity of contraction but only at relatively low levels (up to 20% of maximal voluntary contraction). Such a nonlinear change in muscle thickness during a contraction (i.e., no further increase in thickness despite increasing EMG muscle activity) could potentially lead to a type of ceiling effect for the measurement of TrA thickening. Put simply, it may mean that “good” and “extremely good” performances may not be distinguishable, thereby limiting the ability of ultrasound to differentiate adequately between “well-performing patients” and “even better-performing controls”. Such an effect was, indeed proposed as an explanation for the lack of improvement in TrA contraction ratio seen in patients after ultrasound biofeedback training [41]. It is also possible that, since the test in supine lying does not represent much of a challenge to spinal stability, it might not always detect underlying TrA dysfunction. O’Sullivan described a clinical presentation of direction-specific impairment of spinal stability associated with a dysfunction of the local muscle system [31]. The advantage of our chosen test set-up (a comfortable supine position with a soft support under the knee) was that it allowed measurement even in patients presenting with pain or fear of movement and could be adequately standardized. However, the assessment of AH in positions that better challenge lumbar stability [42] or employ more functional positions such as standing [28] might be better equipped to reveal any impairment in TrA dysfunction. Nonetheless, though sub-group analyses were not part of her main study design, Mew [28] failed to see any notable difference in performance in individuals with a history of LBP compared with controls, whether tested in 4-point kneeling or in standing, and neither were group differences seen in supine lying or 4-point kneeling positions in the recently published study of Gorbet et al. [12]. Overall, it would appear that an impaired ability to activate the TrA in groups of patients with LBP is neither a consistent nor notable finding.

The previous study that reported significant differences between the ultrasound-determined mean TrA contraction ratios of LBP patients and controls [7] did not examine the accuracy of this index to predict group membership on an individual basis. The only studies that have assessed the potential of AH performance in classifying subjects with and without LBP have used the pressure changes measured with a PBU to reflect TrA function. Based on the values measured in 15 subjects, Hodges et al. [16] reported that 80% of the subjects could be correctly categorized as belonging to LBP or non-LBP groups. However, these results have never been replicated by other researchers: Cairns et al. [6] classified 45 patients based on PBU measures during AH and reported either 68 or 60% accuracy in correctly classifying patients as being either “lumbar symptomatic” or not, depending on the specific criteria applied. The use of a different measuring instrument, with its own inherent limitations [39, 44], somewhat limits the comparison with the findings of the present investigation. However, in the ROC analysis in the present study, the AUC for the TrA-contraction ratio was just 0.60 [CI 0.50–0.70], which just failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.07) and was only slightly better than chance (0.5 is equivalent to a non-predictive or random classifier). The AUC was well below our a priori estimate of what would constitute a clinically relevant value, and hence we were unable to conclude that the outcome of the AH test represents a suitable means of distinguishing between cLBP and healthy subjects.

No indication was found during the present investigation to suggest that, compared with the healthy controls, the ability to sustain the TrA contraction during AH was impaired in cLBP patients. The SD for the muscle thickness measured during the contraction was implemented as a simple, pragmatic means of gaining some additional information on this potentially important factor. In clinical practice, some patients appear to have difficulty retaining the preferential TrA contraction whilst maintaining a regular breathing pattern; in the ultrasound image, an inability to sustain the contraction is seen during expiration. If this had been the case in the present study, it might have been reflected in a more variable thickness over the hold period for the cLBP patients. Whilst it is possible that such an effect was not detected because measurements were not limited to the expiration sequence, we consider this unlikely. During data collection, emphasis was given to establishing a correct breathing pattern and subjects received explicit instructions to maintain the contraction during expiration. We hence interpret the findings as showing that the cLBP patients also performed just as well as the controls in their ability to sustain the TrA contraction during AHO.

The low but significant negative correlation between the Roland Morris disability scores and the mean values for the TrA ratio indicated that more severe disability was associated with a poorer AH performance. The relationship was not particularly strong (shared variance, 8%), suggesting that impaired performance during AH is not a consistent determinant or consequence of cLBP-associated disability (with the correlational nature of the relationship precluding conclusions regarding causality or consequentiality). Nonetheless, it did provide some suggestion of an association between AH dysfunction and difficulties in performing everyday activities in cLBP. Whether the findings reflect a general disuse phenomenon or are specific to cLBP requires further investigation.

In summary, our findings suggest that cLBP is weakly associated with a lesser ability to voluntarily activate TrA during AH. Further, the greater the self-rated disability in patients with cLBP, the more the voluntary activation of TrA is compromised. However, the magnitude of these effects was rather small and they were influenced by other confounding variables, and we hence consider them to be of limited clinical relevance. There was no indication that the ability to sustain a steady TrA contraction was impaired in the cLBP patients investigated. The TrA ratio during AH was not considered to be a suitable means to discriminate between cLBP and healthy subjects.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Research Programme NRP 53 “Musculoskeletal Health—Chronic Pain” of the Swiss National Science Foundation (Project 405340-104787/2) We would like to express our thanks to: Prof Beat A. Michel for providing the infrastructure to carry out this work within the Department of Rheumatology and Institute of Physical Medicine, University Hospital Zürich, Switzerland; Thomas Zumbrunn, Clinical Trial Unit, University Hospital Basel, for statistical advice; Doctors Bischoff, Camenzind, Distler, Haltinner, Klipstein, Rörig, Schmidt, Sprott, Stärkle-Bär, Tamborrini, Thoma, Zimmermann (USZ), Bartanusz, Kramers-de Quervain, Marx, Pihan (Schulthess Klinik), Brunner (Balgrist), Kern, Kurmann, Schuler, Stössel and Zoller (GP practices) for referring patients into the study; and all the patients who took part in the study.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Allison GT, Kendle K, Roll S, Schupelius J, Scott Q, Panizza J. The role of the diaphragm during abdominal hollowing exercises. Aust J Physiother. 1998;44:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60369-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmark A. Stability of the lumbar spine. A study in mechanical engineering. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1989;230:1–54. doi: 10.3109/17453678909154177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bland JM, Altman DG. The use of transformation when comparing two means. BMJ. 1996;312:1153. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7039.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunce SM, Hough AD, Moore AP. Measurement of abdominal muscle thickness using M-mode ultrasound imaging during functional activities. Man Ther. 2004;9:41–44. doi: 10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunce SM, Moore AP, Hough AD. M-mode ultrasound: a reliable measure of transversus abdominis thickness? Clin Biomech. 2002;17:315–317. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0033(02)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cairns MC, Harrison K, Wright C. Pressure biofeedback: a useful tool in the quantification of abdominal muscle dysfunction? Physiotherapy. 2000;86:127–138. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9406(05)61155-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Critchley DJ, Coutts FJ. Abdominal muscle function in chronic low back pain patients. Physiotherapy. 2002;88:322–332. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9406(05)60745-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliasson K, Elfving B, Nordgren B, Mattsson E. Urinary incontinence in women with low back pain. Man Ther. 2008;13:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Exner V, Keel P. Erfassung der Behinderung bei Patienten mit chronischen Rückenschmerzen. Schmerz. 2000;14:392–400. doi: 10.1007/s004820070004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Hodges PW. Changes in recruitment of the abdominal muscles in people with low back pain: ultrasound measurement of muscle activity. Spine. 2004;29:2560–2566. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000144410.89182.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Herbert RD, Refshauge K. Specific stabilisation exercise for spinal and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:79–88. doi: 10.1016/S0004-9514(06)70043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorbet N, Selkow NM, Hart JM, Saliba S (2010) No difference in transverse abdominis activation ratio between healthy and asymptomatic low back pain patients during therapeutic exercise. Rehabil Res Pract 2010:Article ID 459738. doi:10.1155/2010/459738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Han TS, Schouten JS, Lean ME, Seidell JC. The prevalence of low back pain and associations with body fatness, fat distribution and height. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:600–607. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henry SM, Westervelt KC. The use of real-time ultrasound feedback in teaching abdominal hollowing exercises to healthy subjects. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:338–345. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2005.35.6.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hides J, Wilson S, Stanton W, McMahon S, Keto H, McMahon K, Bryant M, Richardson C. An MRI investigation into the function of the transversus abdominis muscle during “drawing-in” of the abdominal wall. Spine. 2006;31:E175–E178. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000202740.86338.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodges P, Richardson C, Jull G. Evaluation of the relationship between laboratory and clinical tests of transversus abdominis function. Physiother Res Int. 1996;1:30–40. doi: 10.1002/pri.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodges PW, Pengel LH, Herbert RD, Gandevia SC. Measurement of muscle contraction with ultrasound imaging. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27:682–692. doi: 10.1002/mus.10375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodges PW, Richardson C. Delayed postural contraction of transversus abdominis in low back pain associated with movement of the lower limb. J Spin Disord. 1998;11:46–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Inefficient muscular stabilisation of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain. A motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine. 1996;21:2640–2650. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199611150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kermode F. Benefits of utilizing real-time ultrasound imaging in the rehabilitation of the lumbar spine stabilizing muscles following low back injury in the elite athlete: a singe case study. Phys Ther Sport. 2004;5:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2003.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiesel KB, Uhl T, Underwood FB, Nitz AJ. Rehabilitative ultrasound measurement of select trunk muscle activation during induced pain. Man Ther. 2008;13:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiesel KB, Underwood FB, Mattacola CG, Nitz AJ, Malone TR. A comparison of select trunk muscle thickness change between subjects with low back pain classified in the treatment-based classification system and asymptomatic controls. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:596–607. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2007.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kriese M, Clijsen R, Taeymans J, Cabri J. Segmental stabilization in low back pain: a systematic review. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2010;24:17–25. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1251512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Bruun NH. Low back pain and lifestyle. Part II–obesity. Information from a population-based sample of 29,424 twin subjects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:779–783. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199904150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannion AF, Pulkovski N, Gubler D, Gorelick M, O’Riordan D, Loupas T, Schenk P, Gerber H, Sprott H. Muscle thickness changes during abdominal hollowing: an assessment of between-day measurement error in controls and patients with chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:494–501. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0589-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannion AF, Pulkovski N, Toma V, Sprott H. Abdominal muscle size and symmetry at rest and during abdominal hollowing exercises in healthy control subjects. J Anat. 2008;213:173–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMeeken JM, Beith ID, Newham DJ, Milligan P, Critchley DJ. The relationship between EMG and change in thickness of transversus abdominis. Clin Biomech. 2004;19:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mew R. Comparison of changes in abdominal muscle thickness between standing and crook lying during active abdominal hollowing using ultrasound imaging. Man Ther. 2009;14:690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misuri G, Colagrande S, Gorini M, Iandelli I, Mancini M, Duranti R, Scano G. In vivo ultrasound assessment of respiratory function of abdominal muscles in normal subjects. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:2861–2867. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10122861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neumann P, Gill V. Pelvic floor and abdominal muscle interaction: EMG activity and intra-abdominal pressure. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2002;13:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s001920200027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Sullivan PB. Lumbar segmental ‘instability’: clinical presentation and specific stabilizing exercise management. Man Ther. 2000;5:2–12. doi: 10.1054/math.1999.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5:390–397. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199212000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pulkovski N, Sprott H, Michel B, Gubler D, Mannion AF (2005) Do low back pain patients with unilateral symptoms show side differences in deep abdominal muscle function? In: 11th World Congress on Pain, Sydney, Australia

- 34.Rackwitz B, Bie R, Limm H, Garnier K, Ewert T, Stucki G. Segmental stabilizing exercises and low back pain. What is the evidence? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20:553–567. doi: 10.1191/0269215506cr977oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson C, Jull G, Hodges P, Hides J. Therapeutic exercise for spinal segmental stabilization in low back pain: scientific basis and clinical approach. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson CA, Jull GA. Muscle control–pain control. What exercises would you prescribe? Man Ther. 1995;1:2–10. doi: 10.1054/math.1995.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part 1: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine. 1983;8:141–144. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sapsford RR, Hodges PW, Richardson CA, Cooper DH, Markwell SJ, Jull GA. Co-activation of the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles during voluntary exercises. Neurourol Urodyn. 2001;20:31–42. doi: 10.1002/1520-6777(2001)20:1<31::AID-NAU5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Storheim K, Bo K, Pederstad O, Jahnsen R. Intra-tester reproducibility of pressure biofeedback in measurement of transversus abdominis function. Physiother Res Int. 2002;7:239–249. doi: 10.1002/pri.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teyhen DS. Rehabilitative ultrasound imaging symposium. San Antonio. 2006;36:A1–A3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teyhen DS, Miltenberger CE, Deiters HM, Del Toro YM, Pulliam JN, Childs JD, Boyles RE, Flynn TW. The use of ultrasound imaging of the abdominal drawing-in maneuver in subjects with low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:346–355. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2005.35.6.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teyhen DS, Williamson JN, Carlson NH, Suttles ST, O’Laughlin SJ, Whittaker JL, Goffar SL, Childs JD. Ultrasound characteristics of the deep abdominal muscles during the active straight leg raise test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urquhart DM, Barker PJ, Hodges PW, Story IH, Briggs CA. Regional morphology of the transversus abdominis and obliquus internus and externus abdominis muscles. Clin Biomech. 2005;20:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garnier K, Koveker K, Rackwitz B, Kober U, Wilke S, Ewert T, Stucki G. Reliability of a test measuring transversus abdominis muscle recruitment with a pressure biofeedback unit. Physiotherapy. 2009;95:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]