Abstract

Purpose

To examine if pre-injury health-related factors are associated with the subsequent report of whiplash, and more specifically, both whiplash and neck pain.

Methods

Longitudinal population study of 40,751 persons participating in two consecutive health surveys with 11 years interval. We used logistic regression to estimate odds ratio (OR) for reporting whiplash or whiplash with neck pain lasting at least 3 months last year, related to pre-injury health as indicated by subjective health, mental and physical impairment, use of health services, and use of medication. All associations were adjusted for socio-demographic factors.

Results

The OR for reporting whiplash was increased in people reporting poor health at baseline. The ORs varied from 1.47 (95% CI 1.13–1.91) in people visiting a general practitioner (GP) last year to 3.07 (95% CI 2.00–4.73) in people who reported poor subjective health. The OR associated with physical impairment and mental impairment was 2.69 (95% CI 1.75–4.14) and 2.49 (95% CI 1.31–4.74), respectively. Analysis of reporting both whiplash and neck pain gave somewhat stronger association, with ORs varying from 1.50 (95% CI 1.07–2.09) in people visiting a GP last year to 5.70 (95% CI 3.18–10.23) in people reporting poor subjective health. Physical impairment was associated with an OR of 3.48 (95% CI 2.12–5.69) and mental impairment with an OR of 3.02 (95% CI 1.46–6.22).

Conclusion

Impaired self-reported pre-injury health was strongly associated with the reporting of a whiplash trauma, especially in conjunction with neck pain. This may indicate that individuals have, already before the trauma, adopted an illness role or behaviour which is extended into and influence the report of a whiplash injury. The finding is in support of a functional somatic disorder model for whiplash.

Keywords: Whiplash, Whiplash and neck pain, Longitudinal study, Population study, Pre-injury health

Introduction

The course after a whiplash trauma is for many individuals characterized by a wide variety of long-lasting symptoms [1] without clear objective findings [2], as well as a varying prevalence in different cultures [3, 4]. Several factors associated with whiplash have been investigated to explain these findings.

Collision-related factors seem to have minor or no significance [5]. There is no consistent evidence for pathology and signal changes on medical imaging do not predict outcome [6]. However, high initial neck pain intensity has been found to be an important predictor for the outcome after a whiplash trauma [5, 7]. The significance of psychosocial factors has also been documented in several studies, particularly cognitive factors [8, 9] and coping [10]. Pre-accidental factors have received less focus than collision and post-injury related factors, even though they may play an important role in predicting both injury vulnerability and prognosis, but evidence from research is conflicting. From a best evidence synthesis Carroll et al. [5] reported that some studies found prior neck pain was a strong predictor for post-collision neck pain and interference with work or leisure activities post-collision, whereas other studies showed that pre-accident health and prior pain did not predict outcome.

Hendriks et al. [11] found that self-reported pre-injury health status was not predictive for functional recovery, while Holm et al. [12] and Kivioja et al. [13] found that fair or poor health, neck pain, shoulder pain and headache before the collision were risk factors for severe neck pain post-collision. The association between pre-injury and post-injury neck pain may reflect difficulties in distinguishing prior neck pain from present neck pain, but could also reflect a predetermined vulnerability to neck injury or symptoms after a motor vehicle collision [12].

Pre-injury health is a broad concept that may include both self-reported health and healthcare utilisation such as visiting a physician, hospitalization and use of medication. These aspects might reflect different illnesses and complaints and whether the individual has adopted an illness behaviour or role prior to a whiplash incident.

The aim of this prospective longitudinal study was to explore if poor pre-injury health was associated with increased reporting of whiplash, with or without neck pain, in a large population cohort. Pre-injury health was assessed by self-reported subjective health, physical and mental impairment, visiting a general practitioner (GP) the last year, being hospitalized the past 5 years, and use of analgesics or tranquilizers the last month.

Materials and methods

Study population

The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (the HUNT Study) is a longitudinal population-based survey conducted within the county of Nord-Trøndelag, Norway. Nord-Trøndelag county is located in the central part of Norway and has approximately 126,000 inhabitants. The population is fairly representative of Norway as a whole, although the county is largely rural with small cities with less than 50,000 residents. The HUNT study consists of three cross sectional waves, the first conducted in 1984–86 (HUNT 1), the second in 1995–97 (HUNT 2), and the third in 2006–08 (HUNT 3). At each wave, all inhabitants aged 20 years and above were invited to participate by filling in questionnaires and attend a clinical examination that included measurements of height, weight, blood pressure, and blood glucose. For the present study we used data from the first two waves (i.e., HUNT 1 and 2).

At HUNT 1, 74,599 persons (88.1%) participated, and at HUNT 2, 65,604 (70.6%) chose to participate. A non-responder study at HUNT 1 showed that participation was somewhat lower for men than women, in young and old people compared to middle aged, and among those living in the largest municipalities [14]. Non-participants had slightly higher mortality and morbidity than participants, but this was largely due to older age among non-participants. Also at HUNT 2, the participation rate was higher among women than men, and lowest among the youngest and oldest people [15], but no further data on non-responders and their characteristics exists from the HUNT 2 survey.

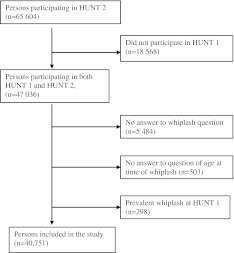

In the present prospective longitudinal study, we included the 47,036 persons who participated in both surveys. Of these, a total of 5,987 subjects were excluded due to missing information related to the whiplash trauma at HUNT 2, and a further 298 subjects who reported whiplash at HUNT 1. This left 40,751 persons with no whiplash trauma at HUNT 1 available for analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of inclusion and exclusion of participants to the study

Study variables

All baseline information on pre-injury health-related factors was obtained from HUNT 1. These included subjective health, physical impairment, mental impairment, visiting a GP last year, hospitalisation past 5 years, use of analgesics, and use of tranquilizers the last month. Subjective health was recorded by asking participants “How do you feel at present?” impairment was recorded by first asking “Do you have any long-term disease, damage or injury of a physical or mental nature which impair your functions in everyday life?”. Participants who answered “yes” to this question where then asked to report if the impairment was due to vision, hearing, physical, or mental causes. In the present study, we used ‘impaired due to physical disease’ and ‘impaired due to mental illness’ as exposure variables. Use of health services was recorded by asking “Have you visited a GP during the last 12 months?”, and “Have you been hospitalized during the last 5 years?” use of medication was recorded by asking “How often have you used analgesics during the last month?” and “How often have you used tranquilizers during the last month?”.

Outcome variables on whiplash and long-term neck pain were obtained from HUNT 2 by the following questions “Have you ever had neck injury (whiplash)?”, and “If yes, please indicate the time for this trauma”. In our study, we only included whiplash traumas occurring in the time period between HUNT 1 and 2. Neck pain was recorded by asking: “During the last year, have you had pain and/or stiffness in the muscles and limbs, which has lasted for at least three consecutive months?” and “If yes, where did you have these complaints?”, with “neck” as the chosen option. All information on exposure and outcome variables was self-reported with no information on reliability or validity in relation to more objective information, e.g., from GP reports.

Potential confounders were recorded at HUNT 1 and included age, gender, marital status and education.

Statistics

We used logistic regression to estimate crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for whiplash associated with pre-injury health-related factors. Similarly, we also estimated ORs for reporting both whiplash and neck pain. Precision of the estimated associations were assessed by a 95% confidence interval (CI). All associations were adjusted for the potential confounding effect of age (continuous), sex (‘male’, ‘female’), education (‘7–9 years primary school’, ‘secondary school’, and ‘college or university’) and marital status (‘married’, ‘unmarried’, ‘widow, divorced or separated’). These are factors that could be related both to pre-injury health and reporting of whiplash [5, 7, 16–18].

In a secondary analysis, we restricted the population to the subgroup of people who all reported neck pain at HUNT 2 to assess if the association with ‘whiplash and neck pain’ was largely driven by an association with the neck pain.

Since neck pain and whiplash were reported as two separate items in the questionnaire, we also conducted analysis of ‘whiplash and neck pain’ restricting cases to whiplash traumas happening 1–5 years before HUNT 2. This was done to reduce the time period between the trauma and the reporting of neck pain in order to increase the likelihood that the neck pain was associated with the whiplash trauma.

All statistical tests were two sided, and all analyses were conducted using SPSS 17 for Windows (SPSS Inc.).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, and a written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Results

In this population-based study of 40,751 individuals, 304 persons reported a whiplash trauma occurring in the time period between the two health surveys and among these, 197 persons also reported neck pain (>3 months last year) at HUNT 2. Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| No whiplash | All whiplash | Whiplash and neck paina | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 40,447 | 304 | 197 |

| Mean age at baseline, years (range) | 44.2 (20–90) | 40.1 (18–73) | 41.0 (21–73) |

| Gender | |||

| Female (%) | 52.6 | 48.7 | 50.8 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married (%) | 75.5 | 69.7 | 69.5 |

| Unmarried (%) | 17.1 | 20.7 | 20.3 |

| Widow, divorced, separated (%) | 6.9 | 7.9 | 9.1 |

| Education | |||

| 7–9 years primary school (%) | 42.6 | 34.5 | 35.5 |

| Secondary school (%) | 31.9 | 36.5 | 38.1 |

| College, university (%) | 9.6 | 12.5 | 7.6 |

| Neck pain* (%) | 26.7 | 64.8 | 100.0 |

aNeck pain lasting ≥3 months during the past year, reported at HUNT 2

*P<0.001

We found strong associations between all measures of self-reported health at baseline and whiplash (Table 2). The OR for all whiplash was three times higher for persons who reported not very good or poor baseline health compared to those who reported very good health (adjusted OR, 3.07; 95% CI 2.00–4.73). For both whiplash and neck pain the association was even stronger (adjusted OR, 5.70; 95% CI 3.18–10.23). Moreover, persons who reported to be moderately or severely impaired, either in relation to physical health or mental health, had more than twice the OR for reporting whiplash compared to people without impairment (adjusted OR, 2.69; 95% CI 1.75–4.14 and 2.49; 95% CI 1.31–4.74, respectively), and a threefold higher OR for ‘whiplash and neck pain’ (adjusted OR, 3.48; 95% CI 2.12–5.69; and adjusted OR, 3.02; 95% CI 1.46–6.22, respectively).

Table 2.

Odds ratio (OR) for overall and ‘whiplash and neck pain’ associated with subjective health

| Variables | No. without whiplash | All whiplash | Whiplash and neck paina | Whiplash 1–5 years before HUNT 2 and neck paina | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | Adjusted ORb (95% CI) | No. of cases | Adjusted ORb (95% CI) | No. of cases | Adjusted ORb (95% CI) | ||

| Self-reported health | |||||||

| Very good | 7,146 | 45 | 1.00 (reference) | 21 | 1.00 (reference) | 13 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Good | 25,683 | 175 | 1.55 (1.13–2.13) | 106 | 1.85 (1.07–3.18) | 63 | 2.28 (1.07–4.85) |

| Not so good/poor | 7,536 | 84 | 3.07 (2.00–4.73) | 70 | 5.70 (3.18–10.23) | 42 | 8.11 (3.64–18.11) |

| Physical impairment | |||||||

| No | 36,304 | 253 | 1.00 (reference) | 154 | 1.00 (reference) | 91 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Slight | 1,962 | 24 | 2.27 (1.44–3.59) | 21 | 3.21 (1.94–5.32) | 12 | 3.83 (2.00–7.33) |

| Moderate/severe | 2,181 | 27 | 2.69 (1.75–4.14) | 22 | 3.48 (2.12–5.69) | 15 | 4.86 (2.66–8.89) |

| Mental impairment | |||||||

| No | 38,912 | 287 | 1.00 (reference) | 183 | 1.00 (reference) | 112 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Slight | 764 | 5 | 1.23 (0.50–2.99) | 4 | 1.50 (0.55–4.07) | 1 | 0.66 (0.09–4.76) |

| Moderate/severe | 771 | 12 | 2.49 (1.31–4.74) | 10 | 3.02 (1.46–6.22) | 5 | 3.26 (1.31–8.15) |

CI confidence interval, GP general practitioner

aNeck pain lasting ≥3 months during the past year, reported at HUNT 2

bAdjusted for baseline age (continuous), gender, education, and marital status

Table 3 shows that use of health care services and use of medication were both associated with whiplash. People who had visited a GP during the past year had an adjusted OR of 1.47; 95% CI 1.13–1.91) compared to those who had not. Those who reported hospitalization during the past 5 years had an adjusted OR of 1.53 (95% CI 1.18–1.98) compared to those who had not been hospitalized. These associations were largely similar to the results of subjects with both whiplash and neck pain.

Table 3.

Odds ratio (OR) for overall and ‘whiplash and neck pain’ associated with use of health services and medication

| Variables | No. without whiplash | All whiplash | Whiplash and neck paind | Whiplash 1–5 years before HUNT 2 and neck paind | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | No. of cases | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | No. of cases | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | ||

| Attending GPb | |||||||

| No | 18,119 | 110 | 1.00 (reference) | 70 | 1.00 (reference) | 40 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 22,295 | 194 | 1.47 (1.13–1.91) | 127 | 1.50 (1.07–2.09) | 78 | 1.76 (1.30–2.77) |

| Hospitalisedc | |||||||

| No | 27,353 | 172 | 1.00 (reference) | 107 | 1.00 (reference) | 62 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 12,976 | 132 | 1.53 (1.18–1.98) | 90 | 1.66 (1.20–2.29) | 56 | 1.98 (1.30–3.03) |

| Use of analgesics | |||||||

| Never | 24,241 | 154 | 1.00 (reference) | 89 | 1.00 (reference) | 53 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Less than weekly | 7,010 | 75 | 1.81 (1.36–2.41) | 50 | 1.99 (1.39–2.85) | 6 | 1.78 (1.09–2.90) |

| Weekly or daily | 2,382 | 27 | 2.07 (1.33–3.22) | 22 | 2.75 (1.67–4.54) | 13 | 2.99 (1.56–5.71) |

| Use of tranquilizers | |||||||

| Never | 29,690 | 210 | 1.00 (reference) | 125 | 1.00 (reference) | 75 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Less than weekly | 2,040 | 22 | 1.76 (1.09–2.86) | 16 | 2.19 (1.26–3.80) | 8 | 1.77 (0.80–3.92) |

| Weekly or daily | 2,039 | 21 | 1.97 (1.22–3.18) | 17 | 2.42 (1.40–4.17) | 9 | 2.10 (0.98–4.49) |

CI confidence interval, GP general practitioner

aAdjusted for baseline age (continuous), gender, education, and marital status

bDuring last year

cduring last 5 years

dNeck pain lasting ≥3 months during the past year, reported at HUNT 2

Using analgesics weekly as opposed to never was associated with an adjusted OR of 2.07 (95% CI 1.33–3.22) for all whiplash, whereas this association increased to an OR of 2.75 (95% CI 1.67–4.54) for those reporting both whiplash and neck pain. The results for use of tranquillizers were largely similar.

To explore whether the associations reported above for both whiplash and neck pain could be associated with neck pain alone rather than the whiplash trauma, we repeated the analyses in a subgroup of individuals all reporting neck pain at HUNT 2 (n = 11,015). In this subgroup, the adjusted OR for whiplash and neck pain was 2.00 (95% CI 1.11–3.60) for persons reporting poor health compared to those who reported very good health; for persons reporting moderate or severe physical impairment the adjusted OR was 1.86 (95% CI 1.13–3.06) compared to those reporting no physical impairment; and for those reporting moderate or severe mental impairment the OR was 2.31 (95% CI 1.11–4.81) compared to those reporting no mental impairment (Table 4). Concerning the more objective exposure variables (use of health services and medication) the ORs varied between 1.12 and 1.52; however, none of these results were statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 4.

The association between subjective health and self-reported whiplash in individuals reporting neck pain

| Variables | Neck painb, no whiplash | Neck painb and whiplash | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | ORa (95% CI) | ||

| Self-reported health | |||

| Very good | 1,092 | 21 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Good | 6,477 | 106 | 1.12 (0.65–1.94) |

| Not very good/poor | 3,227 | 70 | 2.00 (1.11–3.60) |

| Physical impairment | |||

| No | 8,996 | 154 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Slight | 822 | 21 | 1.88 (1.13–3.13) |

| Moderate/severe | 1,000 | 22 | 1.86 (1.13–3.06) |

| Mental impairment | |||

| No | 10,193 | 183 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Slight | 325 | 4 | 0.97 (0.35–2.64) |

| Moderate/severe | 300 | 10 | 2.31 (1.11–4.81) |

aAdjusted for baseline age (continuous), gender, education, and marital status

bNeck pain lasting ≥3 months during the past year, reported at HUNT 2

Table 5.

The association between use of health care services and medication and self-reported whiplash in individuals reporting neck pain

| Variables | Neck paind, no whiplash | Neck paind and whiplash | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | ORa (95% CI) | ||

| Attending GPb | |||

| No | 3,981 | 70 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 6,826 | 127 | 1.12 (0.80–1.56) |

| Hospitalizedc | |||

| No | 6,664 | 107 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 4,119 | 90 | 1.34 (0.97–1.86) |

| Use of analgesics | |||

| Never | 5,278 | 89 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Less than weekly | 2,405 | 50 | 1.34 (0.93–1.93) |

| Weekly or daily | 1,219 | 22 | 1.26 (0.76–2.08) |

| Use of tranquilizers | |||

| Never | 7,249 | 125 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Less than weekly | 799 | 16 | 1.44 (0.83–2.51) |

| Weekly or daily | 878 | 17 | 1.52 (0.88–2.63) |

aAdjusted for baseline age (continuous), gender, education, and marital status

bDuring last year

cDuring last 5 years

dNeck pain lasting ≥3 months during the past year, reported at HUNT 2

To decrease the time period between the occurrence of the whiplash trauma and the reporting of neck pain at HUNT 2, and thereby increase the probability that the reported neck pain was a consequence of the trauma, we excluded all cases of whiplash occurring more than 5 years before participation in HUNT 2 (n = 113). We also excluded cases reporting a whiplash trauma less than 1 year before the participation in HUNT 2 (n = 20). The analyses of both whiplash and neck pain were then repeated. We found that this restriction of the time period resulted in a strengthening of the associations compared to the analyses of the total population (Tables 2, 3, last column). People who reported poor health had an adjusted OR of 8.11 (95% CI 3.64–18.11) compared to those who reported good health, and those who had visited a GP during the past year had an adjusted OR of 1.76 (95% CI 1.30–2.77) compared to those who had not.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study we found that pre-injury health was strongly associated with subsequent reporting of whiplash, and especially with reporting both whiplash and neck pain. Self-reported health displayed a stronger association to whiplash than did use of health care services and use of medication. The results indicated that the subjective pre-injury health of persons reporting whiplash was considerably impaired already before the trauma, particularly in persons reporting both whiplash and neck pain. This could not be explained by the neck pain alone.

Our results are in contrast to findings from a systematic literature review of physical prognostic factors for the development of late whiplash syndrome [19]. Also Ferrari et al. [20] could not find any increase in health problems prior to the trauma in a study of whiplash claimants compared to the general population. However, the information was self-reported by participants who were in a process of litigation. The validity of self-report of previous comorbid disorders and psychological distress in whiplash has been shown to be particularly poor for individuals who are in a process of litigation [21].

In contrast, Lankester et al. [22] and Turner et al. [23] used information from GP reports and found that both physical and psychological outcomes were associated with pre-injury musculoskeletal complaints [23] and with pre-injury back pain, high frequency of GP attendance, anxiety and depression symptoms [22]. It was concluded that these factors may represent vulnerability for a more unfavourable outcome after a neck trauma in a low velocity motor vehicle accident.

McLean [24] found that pre-injury stress or psychological factors were risk factors for the development of chronic symptoms after a traumatic event. e.g., a whiplash trauma, while characteristics of the trauma per se were only of minor importance. What seemed to be important was the worry or expectations of chronic illness, which is in accordance with the concept of a functional somatic disorder [25].

The main strength of this study was the prospective cohort design, with measures of subjective health, use of health services and medication prior to self-report of whiplash injury. The study sample was large and the participation rate was high. The information was further reported as part of a general health survey and neither participants nor administrators were aware of any specific focus or hypothesis.

However, this general health survey design also has limitations. We could not explore the reasons for reporting of poor health at HUNT 1, as the questions concerning the self-reported pre-injury health were broad and non-specific. Both pre-injury anxiety and depression [22, 26] and pre-injury musculoskeletal pain [23] have been associated with whiplash and the course of symptoms after a whiplash injury. It is reasonable to assume that these factors contributed to poor pre-injury health also in this study. These factors might be of generic nature as they are also found in other symptomatic disorders, and are in agreement with the theory of functional somatic syndromes; which have a great overlap in presentation and reporting of symptoms [25].

Another limitation was the self-reporting of both exposure and outcome variables without any clinical verification. Persons self-reporting a whiplash trauma are biased towards recent cases and symptomatic cases [27]. Research also has indicated that those reporting a whiplash trauma might have a higher risk of a subsequent disability pension award [26].

Pre-injury health problems and impairment were also self-reported and not confirmed by clinical examination, and the information was obtained with un-validated instruments. We cannot exclude the possibility that the responses to these questions are biased in relation variables in this study. For example, negative affectivity, anxiety or depression might increase both reporting of pre-injury health problems and later whiplash injury. The reporting of health also might be affected by a demand characteristic encouraging an affirmative response.

Finally, the analyses were adjusted for socio-demographic factors, but residual confounding cannot be excluded.

In our analyses, we used the term ‘both whiplash and neck pain’ as if these two conditions were associated. However, we could not confirm that neck pain was related to the whiplash injury, as the prevalence of neck pain in the population is high [28]. This limitation thus represents a risk of overestimating the neck pain associated with the whiplash trauma. To increase the probability of the association between the whiplash injury and neck pain we performed a subanalysis restricted to cases reporting a more recent whiplash trauma 1–5 years before the report of neck pain at HUNT 2. The results showed that the association was strengthened, indicating that the true associations may be underestimated in our main analyses.

The associations between health-related variables and both whiplash and neck pain were considerably weaker for the subpopulation all reporting neck pain relative to associations found in the main population. This may indicate that the association of whiplash with pre-injury health was partly due to neck pain, possibly by pain present already at HUNT 1. However, the data did not allow us to explore this hypothesis as the HUNT 1 study did not include any questions on neck pain.

The findings from the present study indicate that individuals with poor pre-injury self-reported health may be more liable to report whiplash and particularly reporting both whiplash and neck pain. This could be explained by a number of factors. Persons with poor health may be at a higher risk of experiencing a whiplash trauma as a result of use of medications, reduced concentration and attention; however, a whiplash trauma usually results from a rear end collision where the attention of the victim may be of minor importance. Another explanation could be an attribution hypothesis, suggesting that subjects with previous health complaints, e.g., neck pain or psychological distress, in the trauma find a cause to which they can attribute their health complaints. Finally individuals self-reporting whiplash and particularly both whiplash and neck pain may have a psychological vulnerability characterized by greater body awareness and symptom perception. Thus they may be more susceptible to experience symptoms and to report whiplash traumas. This explanation would be in agreement with the functional somatic disorder model [25].

Conclusion

In this study, impaired self-reported pre-injury health was strongly associated with the reporting of a whiplash trauma, especially in conjunction with neck pain. This might indicate that individuals have, already before the trauma, adopted an illness role or behaviour which is extended into and influence the report of a whiplash injury. The finding is in support of a functional somatic disorder model for whiplash.

Acknowledgments

AM was funded by The Norwegian Research Council. No further support was received. The HUNT study is a collaboration between the HUNT Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, The Norwegian Institute of Public Health, and Nord-Trøndelag County Council.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Wenzel HG, Mykletun A, Nilsen TIL. Symptom profile of persons self-reporting whiplash: a Norwegian population-based study (Hunt 2) Eur Spine J. 2009;18:1363–1370. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1106-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borchgrevink G, Smevik O, Haave I, Haraldseth O, Nordby A, Lereim I. MRI of cerebrum and cervical columna within 2 days after whiplash neck sprain injury. Injury. 1997;28(5–6):331–335. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(97)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chappuis G, Soltermanna B. Number and cost of claims linked to minor cervical trauma in Europe: results from the comparative study by cea, aredoc and ceredoc. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1350–1357. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0732-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm LW, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Hogg-Johnson S, Coté P, Guzman J, Peloso P, Nordin M, Velde G, Carragee E, Halderman S. The burden and determinants of neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders after traffic collisions: results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine. 2008;33(45):S52–S59. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643ece. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Hogg-Johnson S, Coté P, Cassidy JD, Halderman S, Nordin M, Hurwitz EL, Carragee EJ, Velde G, Peloso PM, Guzman J. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders (wad): results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine. 2008;33((S4)):S83–S92. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643eb8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binder A. The diagnosis and treatment of nonspecific neck pain and whiplash. Eura Medicophys. 2007;43:79–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coté P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Frank JW, Bombardier C. A systematic review of the prognosis of acute whiplash and a new conceptual framework to synthesize the literature. Spine. 2001;26(19):E445–E458. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200110010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holm LW, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Skillgate E, Ahlbom A. Expectations for recovery important in the prognosis of whiplash injuries. PLoS Med. 2008;5(5):e105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan MJL, Stanish W, Sullivan ME, Tripp D. Differential predictors of pain and disability in patients with whiplash injuries. Pain Res Manage. 2002;7(2):68–74. doi: 10.1155/2002/176378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buitenhuis J, Spanjer J, Fidler V. Recovery from acute whiplash. The role of coping styles. Spine. 2003;28(9):896–901. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000058720.56061.2A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendriks EJM, Scholten-Peeters GGM, Windt DA, Neeleman-van der Steen CWM, Oostendorp RAB, Verhagen AP, et al. Prognostic factors for poor recovery in acute whiplash patients. Pain. 2005;114(1–2):408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holm LW, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Ahlbom A. Factors influencing neck pain intensity in whiplash-associated disorders in Sweden. Clin J Pain. 2007;27(7):591–597. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318100181f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kivioja J, Jensen I, Lindgren U. Neither the wad-classification nor the Quebec task force follow-up regiment seems to be important for the outcome after a whiplash injury. A prospective study on 186 consecutive patients. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:930–935. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0675-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmen J, Midthjell K, Bjartveit K, Hjort PF, Lund-Larsen PG, Mooun T, Næss S, Waalder H, Th. (1990) The Nord-Trøndelag health survey 1984–86. Purpose, background and methods. Participation, non-participation and frequency distributions. Report 4/90. HUNT Research Centre

- 15.Holmen J, Midthjell K, Krüger Ø, Langhammer A, Holmen T, Bratberg G, Vatten L, Lund-Larsen P. The Nord-Trøndelag health study 1995–97 (HUNT 2): objectives, contents, methods and participation. Norsk Epidemiol. 2003;13:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berglund A, Bodin L, Jensen I, Wiklund A, Alfredsson L. The influence of prognostic factors on neck pain intensity, disability, anxiety and depression over a 2-year period in subjects with acute whiplash injury. Pain. 2006;125(3):244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scholten-Peeters GG, Verhagen AP, Bekkering GE, Windt DA, Barnsley L, Oosendorp RAB, Hendriks EJM, et al. Prognostic factors of whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Pain. 2003;104(1–2):303–322. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter J. Demographic variables and chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(4 Suppl):S14–S19. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200112001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams M, Williamson E, Gates S, Lamb SE, Cooke M. A systematic literature review of physical prognostic factors for the development of late whiplash syndrome. Spine. 2007;32(25):E764–E780. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815b6565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrari R, Russell AS, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD. A re-examination of the whiplash associated disorders (WAD) as a systemic illness. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1337–1342. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.034447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carragee EJ. Validity of self-reported history in patients with acute back or neck pain after motor vehicle accidents. Spine J. 2008;8(2):311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lankester BJA, Garneti N, Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Factors predicting outcome after injury in subjects pursuing litigation. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(6):902–907. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0936-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner MA, Taylor PJ, Neal LA. Physical and psychiatric predictors of late whiplash syndrome. Injury. 2003;34(6):434–437. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(02)00311-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLean SA, Clauw DJ. Predicting chronic symptoms after an acute “stressor”—lessons learned from 3 medical conditions. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63(4):653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barsky AJ, Borus JF. Functional somatic syndromes. Ann Int Med. 1999;130:910–921. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-11-199906010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mykletun A, Glozier N, Wenzel HG, Øverland S, Harvey SB, Wessely S, Hotopf M. Reverse causality in the association between whiplash and anxiety and depression. The HUNT study. Spine. 2011;36(17):1380–1386. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f2f6bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenzel HG, Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. A population study of anxiety and depression among persons who report whiplash traumas. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(3):831–835. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hogg-Johnson S, Velde G, Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Cassidy JD, Guzman J, Coté P, Halderman S, Ammendolia C, Carragee E, Hurwitz E, Nordin M, Peloso P. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine. 2008;33(4S):S39–S51. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816454c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]