Abstract

Ca2+ release events underlie global Ca2+ signaling yet they are regulated by local, subcellular signaling features. Here we review the latest developments of different elementary Ca2+ release features that include Ca2+ sparks, Ca2+ blinks (the corresponding depletion of Ca2+ in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) during a spark) and the recently identified small Ca2+ release events called quarky SR Ca2+ release (QCR). QCR events arise from the opening of only a few type 2 ryanodine receptors (RyR2s) - possibly only one. Recent reports suggest that QCR events can be commingled with Ca2+ sparks and may thus explain some variations observed in Ca2+ sparks. The Ca2+ spark termination mechanism and the number of RyR2 channels activated during a Ca2+ spark will be discussed with respect to both Ca2+ sparks and QCR events.

Keywords: Ca2+ blink, Ca2+ spark, heart, quarky SR Ca2+ release, ryanodine receptor

Introduction

Cardiac contraction underlies the pumping of blood needed to perfuse tissue and thereby deliver nutrients and oxygen. The cardiac action potential (AP) regulates contraction through the process of excitation-contraction (EC) coupling. Invaginations of the plasma membrane extend the surface membrane into the cardiomyocytes through the T-tubule (TT) network found in mammalian ventricular myocytes enabling the AP to control EC coupling throughout the cell. The intracellular Ca2+-rich organelle, the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) is organized so that the primary Ca2+ release component, the junctional SR (jSR) forms a thin pancake like structure that wraps around the TT and that remains within 15 nm of the TT membranes. The Ca2+ release channels (RyR2s) reside in the jSR and span the gap (the subspace) between the TT and jSR membranes. During EC coupling, activation of L-type Ca2+ channel (LCC) by the AP enables a small "puff" of Ca2+ to enter the subspace and activate RyR2s. The activated RyR2s open and permit Ca2+ to move from the jSR lumen into the cytosol. The local [Ca2+]subspace bathes the other RyR2s in the same subspace and they in turn are activated. This process is called Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release (CICR) and it amplifies the initial Ca2+ entry into the cytosol. The measured increase of cytosolic [Ca2+]i due to the activation of RyR2s in one jSR is seen as a Ca2+ spark. The unit of such Ca2+ release, including the LCC, the jSR with its cluster of RyR2s and local structures are called a Ca2+ release unit (CRU). Depending on species, 70 to 90% of the Ca2+ released during EC coupling is through the SR (Bassani et al., 1994). CICR is therefore an important part of the EC coupling. During EC coupling, a [Ca2+]i transient is actually composed of thousands of Ca2+ sparks (Cannell et al., 1994; Lopez-Lopez et al., 1995; Cannell et al., 1995).

Ca2+ spark

Ca2+ sparks can arise when the LCC are opened by depolarization, when local [Ca2+]i is elevated by some other mechanisms but they can also open "spontaneously". Such spontaneous openings occur because each RyR2 has a finite probably of opening even when the diastolic [Ca2+]i is low. While that probably is low, it is sufficient in rat heart cells to underlie a spontaneous Ca2+ spark rate of about 100 per cell per second. In all cases of Ca2+ spark occurrence, there is a component of CICR. Given that [Ca2+]i in the subspace is elevated by the opening of a local LCC or the probabilistic RyR2, this elevated subspace [Ca2+]subspace increases the likelihood that another RyR2 opens. In this manner CICR is a key element in the generation of a Ca2+ spark (Prosser et al., 2010).

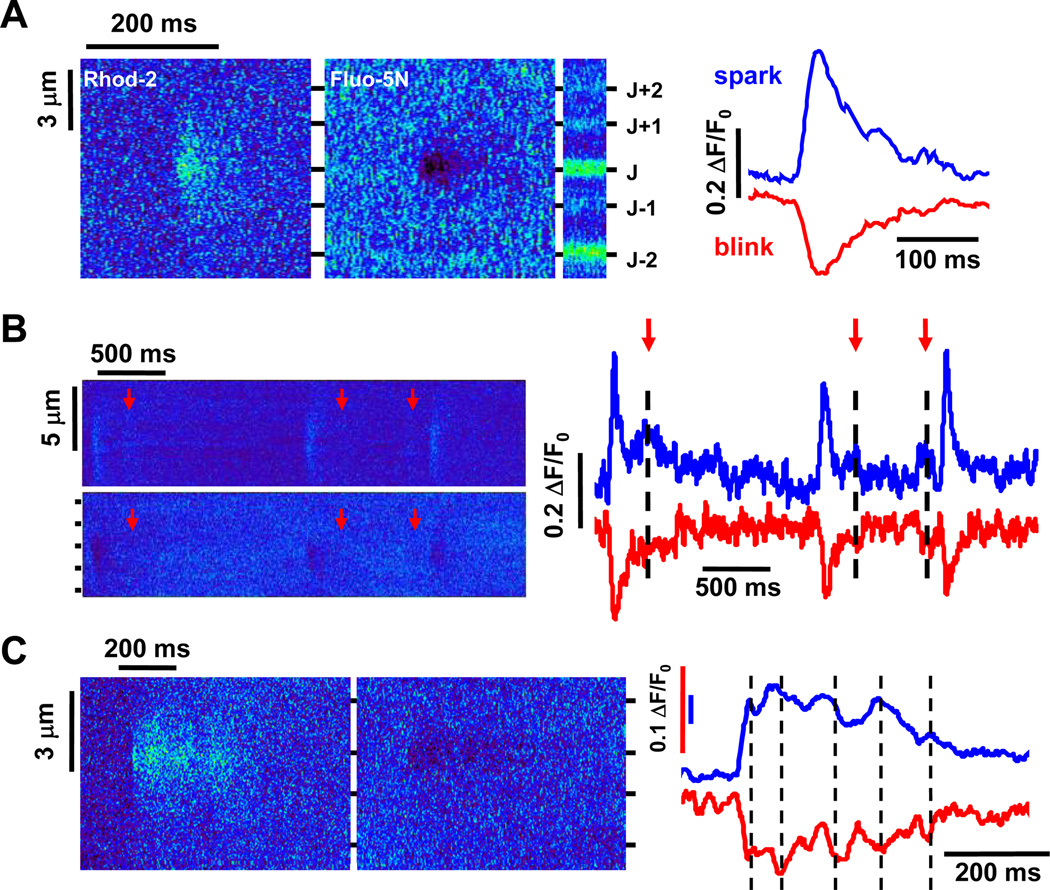

Ca2+ sparks typically are small with a diameter at the peak [Ca2+]i of the spark characterized by the "full width at half-maximum" or FWHM (2 –2.5 µm). They also have a variable amplitude (ΔF/F0 up to about 4) and a short duration (half time of decay of about 20–30 ms, (Cheng et al., 1993)), suggesting a strong termination mechanism (Sobie et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2011)(Fig 1A). The kinetics of Ca2+ sparks reflect the duration of release, the local diffusion of the released Ca2+ and the cytosolic buffering of Ca2+. In the steady-state, the Ca2+ that is released by Ca2+ sparks is balanced by restorative mechanisms such as reuptake of Ca2+ into the SR by the SR/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+-ATPase2a (SERCA2a) and extrusion of Ca2+ from the cell into the extracellular compartment by the plasmalemmal sodium-calcium exchanger and the plasmalemmal Ca2+-ATPase. The mitochondria take up virtually no Ca2+ (Andrienko et al., 2009).

Fig 1. Examples of different elementary Ca2+ release events.

A. Spark-blink pair. Linescan images of a Ca2+ spark (left panel) and its companion Ca2+ blink (mid left panel) after background subtraction with the corresponding time courses (right)in an intact rabbit ventricular myocyte. The enrichment of the fluo-5N dye in the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (jSR)can be seen on the unsubtracted fluo-5N image (mid-right). The spark-blink pair is centered on the jSR band identified as “J”. B. Quarky SR Ca2+ release (QCR) events. Succession of Ca2+ sparks and QCR events on the same jSR (top left) and their companion Ca2+ blinks and quarky SR Ca2+ depletion (QCD) events (bottom left),with the corresponding time courses (right). The arrows indicate the position of QCR and QCD events on the images and time course plots. C. Long spark-blink pair. An example of a long spark (left) and long blink (middle), with the corresponding time courses (right). The dashed lines on the traces show the correspondence between bumps on the spark and dips on the blink.

Ca2+ blink

In cardiac cells, even if the volume of the SR accounts only for a few percent of the total volume of the cell, it has a major role, essentially as a dynamic Ca2+ store. It releases Ca2+ when the RyR2s open and reacquires Ca2+ by means of SERCA2a. The [Ca2+]SR is around 1 mM, about 10,000 times higher than [Ca2+]i in the cytosol. The SR is composed of two compartments: the jSR at the z-bands and the free SR (fSR) that connects the jSRs. In rabbit heart cells, the fSR is connected to the jSR by 4–5 diffusional strictures of only 30 nm in diameter (Brochet et al., 2005), slowing down Ca2+ diffusion into the jSR during a spark and thereby allowing isolation of Ca2+ signaling in the jSR (also relevant for spark termination). The fSR and jSR are interconnected within the cell and form a single network that includes the ER and the nuclear envelope (Wu and Bers, 2006). The fSR forms a diffuse network composed of interconnected narrow tubules whereas the jSR is composed of enlarged cisternae (as much as about 592 nm in diameter and 30 nm in thickness). The RyR2s in the jSR face the TT and LCC. The number of RyR2s at a jSR is comprised between 30 and 300 and forms a 2D paracrystalline array(Franzini-Armstrong et al., 1999) although recent findings (Baddeley et al., 2009; Hayashi et al., 2009) suggest that these arrays are incomplete and may arise from an assemblage of incomplete subclusters. The jSR not only contains the RyR2s but also the high capacity Ca2+ buffer calsequestrin (Franzini-Armstrong, 1980).

The use of the low affinity Ca2+ indicator fluo-5 N which can be targeted to the SR by "loading protocols" has allowed the visualization of Ca2+ within the SR (when the dye can be accumulated preferentially in the jSR) (Kabbara and Allen, 2001; Shannon et al., 2003). The visualization of the depletion of Ca2+ within a jSR during a spark, called Ca2+ blink, was possible because of the diffusional strictures between the fSR and jSR (Brochet et al., 2005). The simultaneous visualization of sparks (on the cytosolic side) and blinks (on the intra-SR side) has allowed a better understanding of the Ca2+ dynamics during a spark (Brochet et al., 2011). The sharpness of blinks (FWHM=1 µm), suggests that SR Ca2+ depletion is largely confined to a single jSR during a spark and therefore that Ca2+ sparks are the result of the activation of a single CRU. The amplitude of jSR Ca2+ depletion during a Ca2+ blink was about 80–85 % of the SR Ca2+ depletion during a full-fledged transient, indicating that the jSR was largely depleted of Ca2+ during a spark.

Quarky SR Ca2+ release (QCR) event

Activation of a single or a few RyR2s during a QCR event

The simultaneous recording of cytosolic [Ca2+] and intra-SR [Ca2+] was the tool needed for a more adequate understanding of the Ca2+ release process. This approach allowed us to examine the distinction between genuine small Ca2+ release events and out of focus sparks. An out of focus Ca2+ spark does not reveal Ca2+ blink signal since the jSR from which the Ca2+ blink signal arises is out of the plane of focus. Indeed, because of the localized FWHM of Ca2+ blinks, this technique has allowed the detection of very small Ca2+ release events (from 1/3 to 1/10 of a spark) with very rapid kinetics (t67=20 ms, (Brochet et al., 2011)) (Fig 1B). Interestingly, these small spontaneous events look similar to previously described sparkless Ca2+ release (quarks) triggered by CICR in guinea-pig under two photon photolysis of caged Ca2+(Lipp and Niggli, 1998).

How can a single RyR2 be activated without activating the array of RyR2s?

The smallest of the SR Ca2+ release events, now identified as "quarky SR Ca2+ release events" or QCR events, reflect the release of Ca2+ from a range of RyR2s - one to a few RyR2s. This raises the question of how can a single RyR2 or a very few RyR2s be activated within a full array of RyR2s without activating the rest of the array by CICR. One possibility is that not all RyR2s behave the same way within an array of RyR2s. For example, it is possible, in principle, that there is a mixture of naive RyR2s and inactivated RyR2s that exist within a cluster of RyR2s at the jSR. If such a condition could occur, then one or a few RyR2s could be activated while the remaining RyR2s may be "pre-inactivated". However, Ca2+ spark properties can be fully modeled without inactivation (Sobie et al., 2006). Another possibility is that RyR2s within the large array may not be activated by opening of a single (or few) RyR2 because of the weak negative allosteric effect of the binding of Mg2+ to RyR2 on the transition of the RyR2 to the open state (Zahradnikova et al., 2010). The most likely explanation, however, is that one RyR2 may activate the RyR2 cluster with a probability significantly less than one (Williams et al., 2011). Our preference for the Williams model arises because it so nicely reproduces diverse experimental findings (e.g. Ca2+ spark rate, variability and modulation as well as SR Ca2+ leak through RyR2s).

In addition to the explanation of Williams et al. (2011), the geometry of the RyR2s within the jSR may importantly contribute to Ca2+ spark features including QCR. Using EM tomography and PALM (photo-activated light microscopy), the organization of the RyR2s within the RyR2 cluster at the jSR is one that is not fully packed (Baddeley et al., 2009; Hayashi et al., 2009). Instead, RyR2s at a jSR appear to be grouped in large number of small arrays of RyR2s of different sizes (from 1 to >100 RyR2s) close one from another. The average RyR2s per array was 14 with larger arrays of 25 RyR2s on average and some superclusters (association of clusters within 100 nm of each other) averaging 22 RyR2s. The physical distance between these arrays of RyR2s of different sizes may then contribute to the diversity in QCR events and Ca2+ sparks.

Spark initiation

The existence of these QCR events raises the question of Ca2+ spark initiation. As one RyR2 within a CRU opens, the probability of other RyR2s opening is increased due to CICR (Cheng and Lederer, 2008; Williams et al., 2011). The amount of Ca2+ flux into the subspace is roughly the same as the amount of Ca2+ influx into the subspace due to the opening of the LCC. The probability of a Ca2+ spark increases significantly as additional RyR2s are activated and as the [Ca2+]subspace increases. We imagine that QCR events would initiate Ca2+ sparks in a similar manner. However, it would be very difficult experimentally to observe QCR initiated Ca2+ sparks because of the rapidity of successive activation of RyR2s within the CRU and the signal-to-noise ratio.

During diastole and in the absence of a triggering LCC, Ca2+ sparks and QCR events still occur. This can happen because there is a finite opening rate of RyR2s that depends on many factors including the phosphorylation state (Valdivia et al., 1995; Marx et al., 2000; Guo et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2007), [Mg2+]i, RyR2 oxidation and nitrosylation states, [Ca2+]SR and many more (Tocchetti et al., 2007; Prosser et al., 2011). The estimated opening rate of RyR2s under diastolic physiologic conditions is about 10−4 s−1 which corresponds to a diastolic Ca2+ spark rate of about 100 sparks per cell per second in rat ventricular myocytes. During diastole, Ca2+ sparks are initiated by the opening rate of the RyR2s. Briefly, then, Ca2+ sparks are initiated by LCC during an AP. As noted above, however, and as modeled by Williams et al. (2011), neither LCC nor RyR2s entrain Ca2+ sparks with 100% fidelity. QCRs arise when the Ca2+ sparks are not triggered.

Complex features of Ca2+ sparks

Mixture of activation of array and rogue RyR2s during a spark

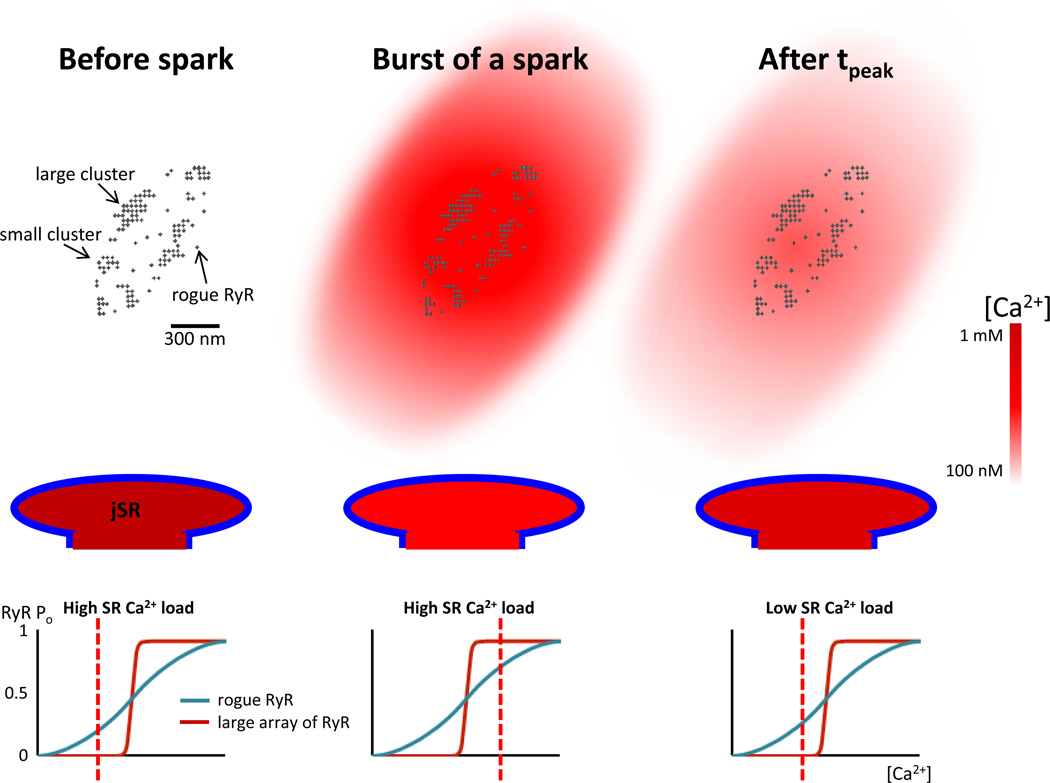

The simultaneous measurement of spark and blink allows a more comprehensive understanding of the Ca2+ release process during a spark. Recent experiments have shown that the duration of Ca2+ release during a spark could be similar to the phase of Ca2+ depletion within the SR during a blink (Brochet et al., 2011). Differences in the kinetics of cytosolic and SR Ca2+ diffusion and Ca2+ buffering may have led to differences in the signals. Importantly, when EGTA was increased in the buffer, the duration of the trailing part of a spark and recovering part of a blink became shorter, suggesting a CICR mechanism during the tail of a spark enabling the Ca2+ spark to last longer. However the rising phase of the Ca2+ sparks was invariant in the presence or absence of EGTA. These results suggest that during the rising phase of a spark, the main array of RyR2s produced enough Ca2+ to sustain the activation. Sobie et al. (2006) suggested that large arrays of RyR2s would be less sensitive to Ca2+ at low Ca2+ than single RyR2 but more sensitive to Ca2+ at high Ca2+. This depended on the cooperativity of RyR2s in a cluster. The large clusters would thus flicker less at low [Ca2+]i and be more constantly activated at high [Ca2+]i. Therefore, despite the decrease of Ca2+ within the jSR during a spark, rogue RyR2s could be repetitively activated during the tail of a spark, prolonging the spark duration, whereas the probability of a large array of RyR2s to be re-activated would be minimal (Fig 2). Thus QCR would have greater variability in Ca2+ spark duration than Ca2+ sparks that originate from within a cluster and that could then explain the variability observed in spark duration (90% of spark t67 between 25 and 95 ms (Brochet et al., 2011)).

Fig 2. Chronology of the events happening during the time course of a Ca2+ spark.

Organization of the different clusters of type 2 ryanodine receptors (RyR2s) at a jSR (top). Before the burst of a Ca2+ spark, all the RyR2s are in a closed state (top left column). The jSR is fully loaded of Ca2+ (mid left column) and the open probability of RyR2s is very low for large array and below 0.5 for rogue RyR2s (bottom left column). During the burst of a Ca2+ spark, the increase in cytosolic Ca2+ activates the large array of RyR2s (open probability very high) and most of the small arrays or rogue RyR2s (open probability superior at 0.5, bottom middle column). The [Ca2+] at the jSR reaches its nadir (mid middle column) whereas the [Ca2+] in the cytosol attains its peak (top middle column). Once the Ca2+ blink has reached its nadir, the low SR [Ca2+] has shifted the activation curves of the large array and rogue RyR2s to the right. The open probability of RyR2s is then very low for large array and below 0.5 for rogue RyR2s (bottom right column). Therefore, only some small arrays or rogue RyR2s will be activated during the tail of a spark (the large array also become refractory). The [Ca2+] in the SR will then increase (mid right column) at the same time as [Ca2+] in the cytosol will diminish (top right column).

This phenomenon may also contribute to the explanation of the occurrence of rare sparks with long kinetics characterized most of the time by a peak followed by an extended plateau (Cheng et al., 1993; Xiao et al., 1997; Zima et al., 2008; Brochet et al., 2011)(Fig 1C). The variation in the amplitude of the plateau suggests that this plateau could correspond to the maintaining of a varying number of opened RyR2s corresponding to small cluster of RyR2s (and not the main cluster anymore) for an extended period of time. Indeed, the absence of these long events in the presence of high EGTA (2 mM) further reinforces the notion of a CICR mechanism in the plateau phase of these long sparks. The similar and simultaneous variation in the amplitude of sparks and blinks during the plateau phase also indicates quick Ca2+ dynamics between the release and refilling of Ca2+, suggesting that the SR is not fully depleted of Ca2+ during the plateau phase of these long events.

Spark termination and refractoriness

The possible opening of small array or rogue RyR2s on the tail of Ca2+ sparks suggests that Ispark is not a square function but rather a triangle function or decreasing function of time (Sobie et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2011). How can then one explain the duration of sparks and its powerful termination scheme? Several mechanisms of spark termination have been proposed over the years. These different mechanisms include the jSR Ca2+ depletion during a spark (Ca2+ blink) that could lead to reduced Ca2+ efflux and RyR2 activation or that may underlie deactivation of the RyR2s from the intra-SR side (Gyorke and Gyorke, 1998). Furthermore, it has been shown that addition of a Ca2+ buffer within the SR prolonged the spark duration, suggesting that SR Ca2+ depletion is an important factor for spark termination (Terentyev et al., 2002). Therefore, a possible mechanism for spark termination could be that as depletion of the SR Ca2+ occurs during a spark, the RyR2s become deactivated from the intra-SR side (Sobie et al., 2002). Rogue RyR2s or small clusters of RyR2s being less sensitive to Ca2+ alterations (Williams et al., 2011) could then shape the kinetics of a spark by being reactivated during the tail of a spark. The plateau phase of long sparks could also be explained by re-activation of small array(s) of RyR2s and rogue RyR2s because of their apparent reduced refractoriness (see below). According to Williams et al. (2011), spark termination could be explained by the reduction of Ca2+ in the jSR (affecting RyR2 Ca2+ sensitivity and Ca2+ efflux) and also by the RyR2 cooperativity (a stochastic version of coupled gating).

However, there are several counter-examples that raise important questions. In our experiments, spark restitution can be longer than blink recovery - as much as 3 times in rabbit (Brochet et al., 2005; Brochet et al., 2011). Complex Ca2+ spark restitution can also arise when RyR2 behavior is changed (Cheng et al., 1993) and spark termination and refractoriness may also be affected by "adaptation" of the RyR2s (Gyorke and Fill, 1993; Valdivia et al., 1995). Phosphorylation of RyR2s can depend on PKA and CaMKII and these changes may occur dynamically and affect termination and refractoriness (Ramay et al., 2011). Recent experiments also show that Ca2+ spark rate can change when RyR2s are oxidized or nitrosylated (Fauconnier et al., 2010; Prosser et al., 2011). Thus refractoriness of local CICR and of Ca2+ sparks will vary as diverse spatial, sensitivity, chemical and triggering features of the CRU may change - including those of rogue RyR2s or small arrays of RyR2s (Brochet et al., 2005; Brochet et al., 2011). In this manner repetitive QCR events may be observed during long sparks (Brochet et al., 2011) and the kinetics of restitution may be dynamic and complex.

How many RyR2sare activated during a spark?

The existence of QCR events suggest that there may be diversity of SR Ca2+ release events and that, in addition to Ca2+ sparks which are the classic SR Ca2+ release event at the 20,000 CRUs per cell, there is an additional population of smaller events with diverse kinetics. As noted above, new imaging approaches that include EM and super-resolution imaging suggest that in addition to the "classic" CRU (Franzini-Armstrong et al., 1999), there are additional organization themes in the CRU (Baddeley et al., 2009; Hayashi et al., 2009). These themes include RyR2 arrays that are spread out as well as those with missing elements. How rogue RyR2s contribute to QCR and normal Ca2+ sparks must still be investigated by those of us examining Ca2+ release by all experimental means and by mathematical modeling.

This brings up the question of how many RyR2s open to produce a spark. With the initial Sobie model of the Ca2+ spark (Sobie et al., 2002), a very broad range of RyR2s could underlie a Ca2+ spark (e.g. 10–100). In order to better characterize the quantitative nature of Ca2+ sparks, Williams et al. (2011) have recently investigated how Ca2+ sparks may arise, how individual RyR2s within the CRU may open and fail to activate a Ca2+ spark and how Ca2+ sparks terminate. This model was based on the latest set of information characterizing RyR2 behavior and information on cardiac ion channels and ion transporters. As with the earlier Sobie model, a wide range of RyR2s may contribute to the Ca2+ spark but the character of the "Ca2+ leak" was better shown with the Williams model. Depending on the spatial geometry, the sensitivity of the RyR2s and the dynamics of the signal regulation, this modeling may help us understand QCR and their dynamics.

In conclusion, our understanding of RyR2 geometry in the CRU (with both tight clusters and loose clusters and with rogue RyR2s) provides an important background. It complements new information on the dynamic modulation of RyR2 sensitivity. Together they provide a background that will enable us to account for QCR events and organize experiments to investigate how QCRs contribute to Ca2+ sparks, normal Ca2+ signaling and pathological behavior.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging (to D.Y.); National Institute of Heart Lung and Blood grants (R01 HL106059, R01 105239 and P01 HL67849), Leducq North American-European Atrial Fibrillation Research Alliance, European Community's Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007–2013 under grant agreement No. HEALTH-F2-2009-241526, EUTrigTreat, and support from the Maryland Stem Cell Commission (to W.J.L.); the Chinese Natural Science Foundation (30630021) and the Major State Basic Science Development Program (2007CB512100, 2011CB809100) (to H.C.).

Abbreviations

- AP

action potential

- CICR

Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release

- CRU

Ca2+ release unit

- EC coupling

excitation-contraction coupling

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FWHM

full-width at half maximum

- LCC

L-type Ca2+ channel

- QCD

quarky SR Ca2+ depletion

- QCR

quarky SR Ca2+ release

- RyR2

type 2 ryanodine receptor

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- fSR

free SR

- jSR

junctional SR

- SERCA2a

SR/ER Ca2+ ATPase2a

- TT

T-tubule

Reference List

- Andrienko TN, Picht E, Bers DM. Mitochondrial free calcium regulation during sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release in rat cardiac myocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley D, Jayasinghe ID, Lam L, Rossberger S, Cannell MB, Soeller C. Optical single-channel resolution imaging of the ryanodine receptor distribution in rat cardiac myocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:22275–22280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908971106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassani JW, Bassani RA, Bers DM. Relaxation in rabbit and rat cardiac cells: species-dependent differences in cellular mechanisms. J. Physiol. 1994;476:279–293. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochet DX, Xie W, Yang D, Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Quarky calcium release in the heart. Circ. Res. 2011;108:210–218. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochet DX, Yang D, Di Maio A, Lederer WJ, Franzini-Armstrong C, Cheng H. Ca2+ blinks: rapid nanoscopic store calcium signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:3099–3104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500059102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MB, Cheng H, Lederer WJ. The control of calcium release in heart muscle. Science. 1995;268:1045–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.7754384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MB, Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Spatial non-uniformities in [Ca2+]i during excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac myocytes. Biophys. J. 1994;67:1942–1956. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80677-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Calcium sparks. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1491–1545. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science. 1993;262:740–744. doi: 10.1126/science.8235594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauconnier J, Thireau J, Reiken S, Cassan C, Richard S, Matecki S, Marks AR, Lacampagne A. Leaky RyR2 trigger ventricular arrhythmias in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:1559–1564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908540107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzini-Armstrong C. Structure of sarcoplasmic reticulum. Fed. Proc. 1980;39:2403–2409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F, Ramesh V. Shape, size, and distribution of Ca(2+) release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1528–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77000-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Zhang T, Mestril R, Bers DM. Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation of ryanodine receptor does affect calcium sparks in mouse ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 2006;99:398–406. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000236756.06252.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorke I, Gyorke S. Regulation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor channel by luminal Ca2+ involves luminal Ca2+ sensing sites. Biophys. J. 1998;75:2801–2810. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77723-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorke S, Fill M. Ryanodine receptor adaptation: control mechanism of Ca(2+)-induced Ca2+ release in heart. Science. 1993;260:807–809. doi: 10.1126/science.8387229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Martone ME, Yu Z, Thor A, Doi M, Holst MJ, Ellisman MH, Hoshijima M. Three-dimensional electron microscopy reveals new details of membrane systems for Ca2+ signaling in the heart. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:1005–1013. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbara AA, Allen DG. The use of the indicator fluo-5N to measure sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium in single muscle fibres of the cane toad. J. Physiol. 2001;534:87–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp P, Niggli E. Fundamental calcium release events revealed by two-photon excitation photolysis of caged calcium in Guinea-pig cardiac myocytes. J. Physiol. 1998;508:801–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.801bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Lopez JR, Shacklock PS, Balke CW, Wier WG. Local calcium transients triggered by single L-type calcium channel currents in cardiac cells. Science. 1995;268:1042–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.7754383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell. 2000;101:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser BL, Ward CW, Lederer WJ. Subcellular Ca2+ signaling in the heart: the role of ryanodine receptor sensitivity. J. Gen. Physiol. 2010;136:135–142. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser BL, Ward CW, Lederer WJ. X-ROS signaling: rapid mechano-chemo transduction in heart. Science. 2011;333:1440–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.1202768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramay HR, Liu OZ, Sobie EA. Recovery of cardiac calcium release is controlled by sarcoplasmic reticulum refilling and ryanodine receptor sensitivity. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011;91:598–605. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon TR, Guo T, Bers DM. Ca2+ scraps: local depletions of free [Ca2+] in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum during contractions leave substantial Ca2+ reserve. Circ. Res. 2003;93:40–45. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000079967.11815.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobie EA, Dilly KW, dos Santos CJ, Lederer WJ, Jafri MS. Termination of cardiac Ca(2+) sparks: an investigative mathematical model of calcium-induced calcium release. Biophys. J. 2002;83:59–78. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75149-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobie EA, Guatimosim S, Gomez-Viquez L, Song LS, Hartmann H, Saleet JM, Lederer WJ. The Ca2+ leak paradox and rogue ryanodine receptors: SR Ca2+ efflux theory and practice. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2006;90:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terentyev D, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Valdivia HH, Escobar AL, Gyorke S. Luminal Ca2+ controls termination and refractory behavior of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 2002;91:414–420. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000032490.04207.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocchetti CG, Wang W, Froehlich JP, Huke S, Aon MA, Wilson GM, Di BG, O'Rourke B, Gao WD, Wink DA, Toscano JP, Zaccolo M, Bers DM, Valdivia HH, Cheng H, Kass DA, Paolocci N. Nitroxyl improves cellular heart function by directly enhancing cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ cycling. Circ. Res. 2007;100:96–104. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000253904.53601.c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia HH, Kaplan JH, Ellis-Davies GC, Lederer WJ. Rapid adaptation of cardiac ryanodine receptors: modulation by Mg2+ and phosphorylation. Science. 1995;267:1997–2000. doi: 10.1126/science.7701323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GS, Chikando AC, Tuan HT, Sobie EA, Lederer WJ, Jafri MS. Dynamics of Calcium Sparks and Calcium Leak in the Heart. Biophys. J. 2011;101:1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Bers DM. Sarcoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope are one highly interconnected Ca2+ store throughout cardiac myocyte. Circ. Res. 2006;99:283–291. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000233386.02708.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao RP, Valdivia HH, Bogdanov K, Valdivia C, Lakatta EG, Cheng H. The immunophilin FK506-binding protein modulates Ca2+ release channel closure in rat heart. J. Physiol. 1997;500:343–354. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Zhu WZ, Xiao B, Brochet DX, Chen SR, Lakatta EG, Xiao RP, Cheng H. Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II-dependent phosphorylation of ryanodine receptors suppresses Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves in cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 2007;100:399–407. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258022.13090.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahradnikova A, Valent I, Zahradnik I. Frequency and release flux of calcium sparks in rat cardiac myocytes: a relation to RYR gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 2010;136:101–116. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zima AV, Picht E, Bers DM, Blatter LA. Termination of cardiac Ca2+ sparks: role of intra-SR [Ca2+], release flux, and intra-SR Ca2+ diffusion. Circ. Res. 2008;103:105–115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.183236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]