Abstract

Chromatin remodelling enzymes such as the histone deacetylases (HDACs) and histone demethylases such as lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) have been validated as targets for cancer drug discovery. Although a number of HDAC inhibitors have been marketed or are in human clinical trials, the search for isoform-specific HDAC inhibitors is an ongoing effort. In addition, the discovery and development of compounds targeting histone demethylases are in their early stages. Epigenetic modulators used in combination with traditional antitumor agents such as 5-azacytidine represent an exciting new approach to cancer chemotherapy. We have developed multiple series of HDAC inhibitors and LSD1 inhibitors that promote the re-expression of aberrantly silenced genes that are important in human cancer. The design, synthesis and biological activity of these analogues is described herein.

1. Introduction

Histones and chromatin structure

Chromatin architecture is a key determinant in regulating gene expression, and is strongly influenced by post–translational modifications of histones. Histones, which are the chief protein component of chromatin, are complex macromolecules comprised of core protein subunits termed H2a, H2b, H3, and H4. These core histone subunits differ slightly in primary sequence and 3-dimensional structure. Histones occur as octamers that consist of one H3-H4 tetramer and two H2A-H2B dimers.1–3 Approximately 146 base pairs of DNA are wrapped around each histone octamer in left-handed superhelical turns, forming a unit known as a nucleosome.4 Nucleosomes, and thus higher order chromatin, are assembled through the cooperative action of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers5 and histone chaperone proteins6 such as FACT7 and the HIR complex.8 Multiple nucleosomes form and ultimately condense through several levels of compaction to form chromatin.9 Lysine-containing histone tails, consisting of up to 40 amino acid residues, protrude through the DNA strand; and lysines, arginines and serines on this tail act as sites for post-translational modification. These modifications allow alteration of higher order nucleosome structure, and thus contribute to structural changes in chromatin.10 Methylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, ADP-ribosylation and acetylation of histone lysine residues and histone serine phosphorylation are known post-translational histone modifications,11 with acetylation being the best characterized process.12 Post-translational modifications of histone tails produce epigenetic changes in gene expression via mechanisms that do not involve changes to the primary DNA sequence. Changes that are created at the epigenetic level persist during the lifetime of the cell, and can be passed on for multiple generations.13 There is an increasing body of evidence that suggests that aberrant epigenetic silencing caused by over expression of histone deacetylases and histone demethylases plays a significant role in the development of cancer and other diseases.14 Drug discovery efforts have mainly concentrated on histone acetylation/deacetylation, but more recently histone methylation/demethylation enzymes have become validated targets for drug discovery.15

2. Inhibitors of histone deacetylases

The acetylation status of histones is controlled by a balance between two enzymes, histone acetyltransferase (HAT), which promotes histone hyperacetylation, and the histone deacetylases (HDACs), which catalyze acetyl group cleavage.12,16 Acetylation of the ε-amino groups of lysine residues located at N-termini removes their positive charge and loosens tightly wound DNA, forming euchromatin and allowing greater access by transcription factors and RNA polymerase. Methylation of DNA, an important event in epigenetic silencing,17 results in recruitment of HDACs. Deacetylation of lysine tails then restores the positive charge and thus promotes formation of tightly wound facultative heterochromatin, resulting in gene silencing. Normal mammalian cells exhibit an exquisite level of control of chromatin architecture by maintaining a balance between HAT and HDAC activity. Histone lysine acetylation status is further controlled by protein-protein interactions, wherein lysine acetylation results in the recruitment of bromodomain-containing transcriptional coactivators such as p300 and cyclic AMP-responsive element (CREB) binding protein.18,19 The bromodomain found in these proteins is the only known protein domain that acts as an acetylated lysine-binding element.20 These coactivators have inherent autocatalytic acetyltransferase activity, and also recruit transcription factors into a complex that promotes active gene transcription.12,21 Aberrant HDAC overexpression results in reduction of acetylated lysine and the loss of bromodomain-containing proteins, leading to transcriptional repression. HDAC inhibitors have been shown to synergize with p300 autoacetylation to restore acetyl lysine levels and the binding of bromodomain-containing transcription factors, activating transcription.19 This series of events promotes the expression of various transcriptional products.

Histone deacetylases and cancer

There are 11 known zinc-dependent HDAC isoforms22–24 that belong to 4 structural classes: class I (isoforms 1, 2, 3 and 8),25 class IIa (isoforms 4, 5, 7 and 9),22 class IIb (isoforms 6 and 10)22 and class IV (HDAC 11).22 In addition to the zinc-dependent HDACs, class III HDACs include sirtuins 1 though 7, which have homology to yeast Sir2 and require NAD+,26 but because they do not require zinc, they are unresponsive to known HDAC inhibitors. In some tumor cell types, aberrant hypocetylation of histones results in the underexpression of growth regulatory factors such as the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p21Waf1, and thus contributes to the development of cancer.2,12 This effect can result from hypermethylated CpG islands occupied by methyl-CpG binding proteins (MBPs) that mediate the effect of histone methylation on chromatin structure.27 Four major classes of MBPs have been identified: chromodomains, Tudor domains, the WD40 repeat and the PHD domain. Binding of MBDs represses transcription of methylated DNA through the recruitment of a histone deacetylase (HDAC)-containing complex, resulting in excessive histone lysine deacetylation. These results are typically seen in addition to a variety of cell signaling aberrations that occur in response to excessive histone deacetylation. The end result is the removal of tumor cells from the cell cycle, cessation of apoptosis and proliferation of undifferentiated tumor cells. HDAC isoform over expression patterns differ in different types of cancer, and in some cases correlate with poor prognosis.28

Histone deacetylase inhibitors as an antitumor strategy

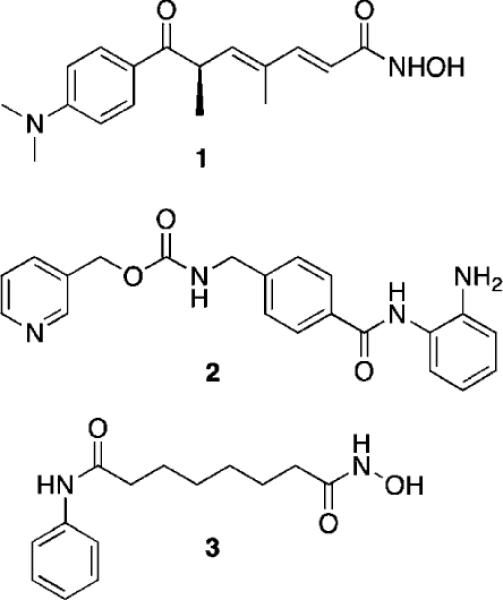

Inhibition of aberrant histone deacetylation by HDAC inhibitors such as trichostatin A (TSA, 1), MS-275 (2) and SAHA (3) (Fig. 1) can cause growth arrest in a wide range of transformed cells, and can inhibit the growth of human tumor xenografts.29 Subsequently, several HDAC inhibitors have been approved for use or are in human clinical trials, largely for hematological cancers.15,30 Although a few HDAC inhibitors have shown selectivity towards a given isoform or class of HDAC, no truly isoform-specific HDAC inhibitors have been identified. Such molecules would be of great value in elucidating the roles of HDAC isoforms in both normal and cancerous cell lines.

Fig. 1.

Structures of trichostatin A (1), MS-275 (2) and SAHA (3).

Current structure/activity studies involving analogues of 1–3 have focused largely on modifications to the aromatic ring moiety and the aliphatic linker region of these molecules (Fig. 2).15,29 Although they are effective both in vitro and in vivo, HDAC inhibitors typified by 1–3 suffer from lack of specificity among the 11 HDAC isoforms, thus producing unacceptable off-target toxicity in non-cancerous cells. Clinical studies indicate that HDAC inhibitors such as 2 and 3 are effective therapies for human cancer,31 but dose-limiting toxicity remains a problem.32 Thus it would be desirable to identify potent HDAC inhibitors that restore the expression of normal tumor suppressor genes without producing significant dose-limiting toxicity.

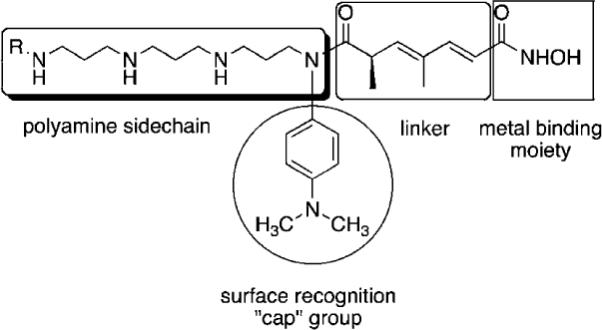

Fig. 2.

Model for design of polyamine-based HDAC inhibitors.

As mentioned above, HDAC inhibitors such as 1–3 and their homologues typically contain three structural features that are thought to be required for optimal activity: an aromatic cap group, an aliphatic chain and a metal binding functional group. As an extension of this paradigm, we designed polyamine-based HDAC inhibitors using the structural model shown in Fig. 2. Mammalian cells contain a polyamine cellular transport system which has been shown to be up regulated in rapidly proliferating cells, including tumor cells.33 This transport system accepts a wide range of compounds, and as such polyamine side chains have been appended to drug molecules and used as a means to increase their cellular uptake.34 Since the polyamine transporter in normal mammalian cells operates at a basal level, this approach provides a means to selectively deliver drug to tumor cells. We postulated that polyamine-based HDAC inhibitors could enter cells using the polyamine transport system, and could be selectively directed to DNA, and thereby to the associated HDACs, by virtue of the positively charged polyamine portion of the structure. Grozinger and Schreiber compared the primary sequences of the 11 HDAC isoforms, and determined that there was significant sequence homology among all 11 isoforms in the binding pocket occupied by 1–3, including the metal binding pocket, the linker chain region and the surface recognition cavity that binds to the aromatic cap group (see Fig. 2). By contrast, the area immediately outside the binding pocket, known as the rim region, features a much lower degree of sequence homology among HDAC isoforms, leading to the hypothesis that inhibitors may be designed to interact with the rim region in an isoform-specific manner.25 We hypothesized that it may be possible to produce isoform specific inhibitors for individual HDAC isoforms by adding polyamine chains to the base structure of 1–3, and by varying the terminal alkyl group on that chain. To this end, we initially synthesized a series of 16 polyaminohydroxamic acid (PAHA) derivatives that incorporated structural features of the polyamines spermidine and spermine and the hydroxamic acid moiety, linker and cap groups commonly found in active HDAC inhibitor molecules such as SAHA. The synthetic route to PAHA derivatives has been previously described by our group.35 Three PAHA analogues from this initial series, compounds 4, 5 and 6 (Fig. 3) reduced global HDAC activity by 74.9, 60.0 and 73.9%, respectively, at a 1 μM concentration. Compound 6 at 1 μM was compared to 5 μM 2 for the ability to promote hyperacetylation of histones H3 and H4 in the ML-1 cell line, and produced significantly higher levels of these proteins than 2 after 24 h, as determined by Western blot analysis.35 Re-expression of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p21Waf1, which is under expressed in leukemias, was also determined in the presence of 6 and MS-275, and 6 was found to be two-fold more effective than 2 at promoting the re-expression of this protein. Taken together, these data suggest that PAHA analogue 6 produces more dramatic effects on ML-1 histone acetylation and gene expression than 2. Interestingly, 4–6 were significantly less cytotoxic than either 1 or 2; this feature may be therapeutically exploitable in that the re-expression of previously inactivated growth regulatory genes without overt cytotoxicity may restore somewhat normal growth control to transformed cells, thus making them less tumorigenic and potentially more susceptible to combination treatment with other cytotoxic agents.

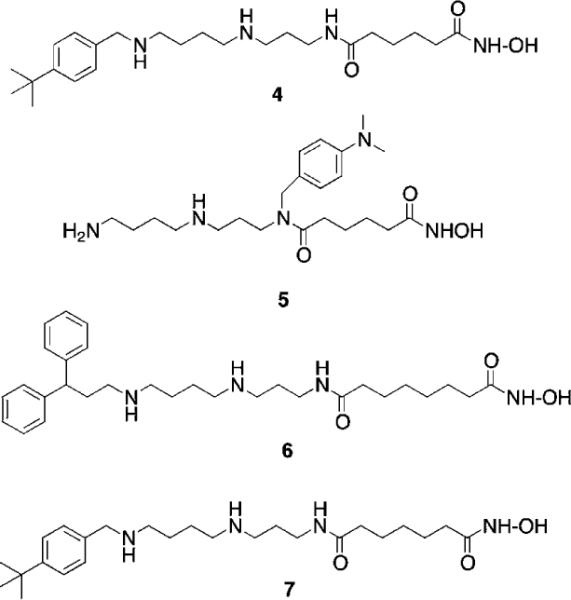

Fig. 3.

Structures of PAHA HDAC inhibitors 4–7.

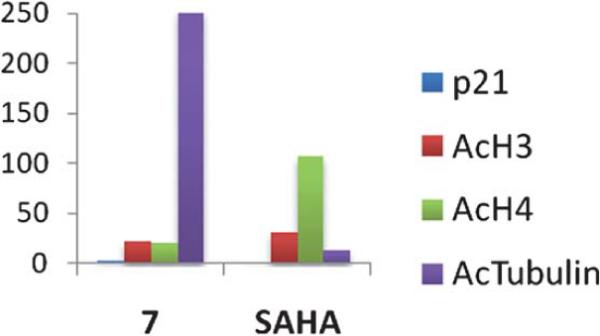

In subsequent studies, 16 additional PAHA analogues were examined, and 5 of these compounds were highly effective HDAC inhibitors. They promoted moderate increases in histone H3 and H4 acetylation and the re-expression of p21waf1, and had low levels of cytotoxicity in HCT116 colon tumor cells.36 Compound 7 (Fig. 3) was found to have an IC50 of 0.9 μM against global HDAC in vitro, but had an IC50 value greater than 100 μM against HCT116 cells in culture. Although 7 had minimal effects on p21 expression and H4/H4 acetylation, it produced a 253-fold increase in acetylated α-tubulin (Fig. 4), indicating that it acts as a selective HDAC 6 inhibitor. Although 7 and related PAHA analogues clearly are taken up into cells and have access to histones, they did not serve as substrates for the polyamine transport system as measured by a 14C-spermidine competition assay. The data for compound 7 reinforces the important concept that epigenetic modulators do not need to be cytotoxic to have significant effects on gene expression in tumor cells. We hypothesize that the use of these HDAC inhibitors in combination with a traditional agent such as 5-azacytidine (5-AC) could allow both compounds to be given at lower doses and still produce synergistic tumor growth inhibition. In vitro experiments to test this hypothesis are currently underway.

Fig. 4.

Fold increase in the re-expression of p21Waf1, acetylated histones H3 (AcH3) and H4 (AcH4), and acetylated α-tubulin proteins in HCT116 colon carcinoma cells. Cells were treated for 24 h with a 10 μM concentration of 7 or SAHA. These data were extracted from original graphs that were published in ref. 36.

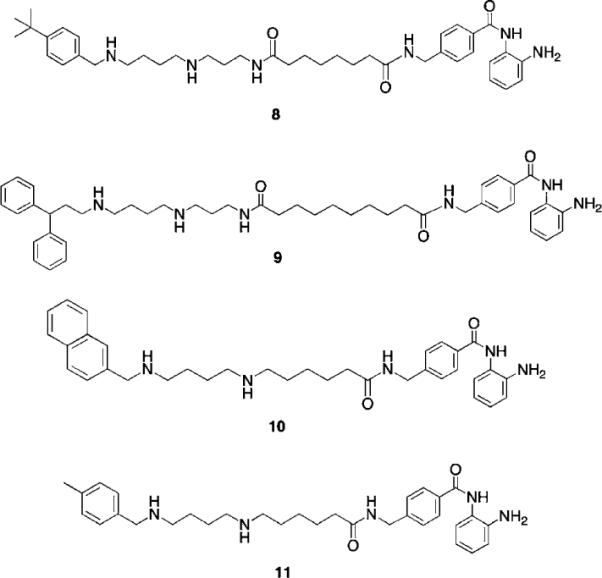

To explore additional metal binding moieties that might facilitate import of the analogues by the polyamine transport system, a series of 40 polyaminobenzamides (PABAs) were synthesized and evaluated as inhibitors of global HDAC.36 Representative structures for this class are shown in Fig. 5. Compound 8 exhibited an IC50 value against global HDAC of 4.9 μM, which is comparable to the reported IC50 value for the benzamide HDAC inhibitor 2 (4.8 μM). Analogues in the PABA series were then evaluated against 4 HDAC isoforms representing Class I (HDAC 1, 3 and 8) and Class II (HDAC 6). In these analogues, structural modifications were made in the linker chain length, in the polyamine substituent and in some cases in the metal binding moiety. These experiments were conducted by employing the commercially available Fluor de Lys® assay kit containing a HeLa cell lysate as the source of HDAC (as a mixture of all 11 isoforms), and substituting the appropriate amount of each pure HDAC isoform in place of the lysate. Isoform selectivity among the HDAC isoforms evaluated varied significantly (unpublished findings), demonstrating that global percent HDAC inhibition is a composite of strong and weak inhibition at different isoforms, and suggesting that the observed HDAC selectivity with PAHAs such as 7, and PABAs such as 9 (see below) may be in part due to structural variations in their polyamine side chains. As mentioned above, one of the potential advantages of incorporating polyamine side chains into PAHA and PABA HDAC inhibitors was that the resulting molecules could utilize the polyamine transport system. Our preliminary data (not shown) demonstrates that PABAs such as 8 are effectively imported using the polyamine transport system, as verified by 14C-spermidine uptake competition assays.36

Fig. 5.

Structures of PABA HDAC inhibitors 8–11.

Three of the most active global HDAC inhibitors in the PABA series, compounds 9, 10 and 11, were found to be markedly selective for HDAC1 (data not shown), an HDAC isoform that is over expressed in a variety of human cancers. For this reason, 9–11 were evaluated against MCF7 wild type breast tumor cells in vitro using an MTA reduction assay. Over a range of concentrations between 0.3 and 30 μM, PABA 9 was inactive, while 10 was cytostatic. However, PABA 11 was cytotoxic in the MCF7 cell line, with a 96-hour IC50 of 0.9 μM. In the MCF10A nontumorigenic breast epithelial cell line, 11 exhibited a 96-hour IC50 of 24 μM, thus demonstrating a greater than 25-fold selectivity for tumor cells. Under the same conditions, SAHA exhibited 96 h IC50 values of 8.5 μM (MCF7) and 31 μM (MCF10A), and thus 11 compares favorably to known HDAC inhibitors that are currently in us in the clinic. Microscopic examination of treated cells revealed that the cytotoxicity in MCF7 cells treated with 11 was mediated by apoptosis.

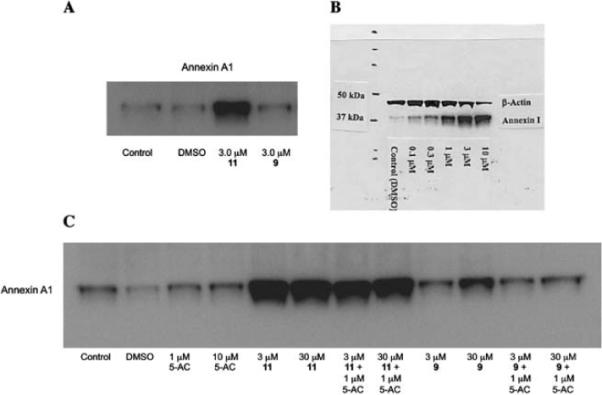

Subsequent mechanistic experiments showed that 11, but not 9, promoted the induction of the protein annexin A1. Upon induction, annexin A1 inhibits the NF-κB signal transduction pathway, which allows tumor cells to proliferate and escape apoptosis. Annexin A1 inhibits the activation of NF-κB by binding to the p65 subunit.37 HDAC inhibitors have been shown to promote apoptosis through induction of annexin A1,38 and recent studies suggest that breast tumors expressing high levels of annexin A1 are more likely to respond to chemotherapy than cells with low levels of annexin A1.39 Additional research is required to determine whether there is a functional relationship between inhibition of a specific HDAC isoform and induction of annexin A1. The variable effects of compounds 9 and 11 on annexin A1 induction are shown in Fig. 6. At a concentration of 3.0 μM, the cytotoxic HDAC inhibitor 11 produced a dramatic induction of annexin A1 (Fig. 6, Panel A), while the non-toxic HDAC inhibitor 9 had no effect on the levels of this protein. The effect of 11 on annexin A1 was dose-dependent over a concentration range of 0.3 to 3.0 μM (Fig. 6, Panel B). As shown in Fig. 6, Panel C, this effect was not observed in the presence of 1 or 10 μM 5-AC, nor did 5-AC enhance the induction of annexin A1 by 11. Experiments to determine the functional link between HDAC inhibition by 11, annexin A1 induction and cytotoxicity are now being conducted.

Fig. 6.

Induction of annexin A1 by PABA HDAC inhibitors 9 and 11. Panel A: Induction of annexin A1 in MCF7 human breast tumor cells by 9 and 11 at 3.0 μM; Panel B: Dose dependence of annexin A1 induction by compound 11 (0.3 to 3.0 μM) in MCF7 cells; Panel C: Effects of compounds 9 or 11 on annexin A1 alone or in combination with 5-AC.

3. Inhibitors of the histone demethylase LSD1

In cancer, DNA promoter hypermethylation in combination with other chromatin modifications, including decreased activating marks and increased repressive marks on histone proteins 3 and 4, are associated with the silencing of tumor suppressor genes.40 The important role of promoter CpG island methylation and its relationship to covalent histone modifications has recently been reviewed.17 As was mentioned above, the N-terminal lysine tails of histones can undergo numerous post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation, ubiquitination, acetylation and methylation.41–43 To date, 17 lysine residues and 7 arginine residues on histone proteins have been shown to undergo methylation,44 and lysine methylation on histones can signal transcriptional activation or repression, depending on the specific lysine residue involved.45–47 Histone methylation is not a static modification, and has recently been shown to be a dynamic process regulated by the addition of methyl groups by histone methyltransferases and removal of methyl groups from mono- and dimethyllysines by lysine specific demethylase 1 (LSD1), LSD2,48,49 and other demethylases such as JMJD2C/GASC1,42,50 and from trimethyllysines by specific Jumonji C (JmjC) domain-containing demethylases.42,43,51,52 Additional histone lysine demethylases are continuing to be identified.53,54 It has recently been demonstrated that LSD1 demethylates K370me1 and K370me2 on the p53 tumor suppressor and transcriptional activator protein, indicating that LSD1 also plays a role in demethylation of non-histone proteins.55 A key positive chromatin mark found associated with promoters of active genes is histone 3 dimethyllysine 4 (H3K4me2).56,57 LSD1, also known as BHC110,42,58 catalyzes the oxidative demethylation of histone 3 methyllysine 4 (H3K4me1) and H3K4me2, and is associated with transcriptional repression. H3K4me2 is a transcription-activating chromatin mark at gene promoters, and demethylation of this mark by LSD1 may prevent expression of tumor suppressor genes important in human cancer.59 Importantly, the combination of chromatin marks at a given promoter determines, in part, whether specific promoters are in an open/active conformation or closed/repressed conformation.10,60 Thus, LSD1 is an important new target for the development of specific inhibitors as a new class of antitumor drugs.61

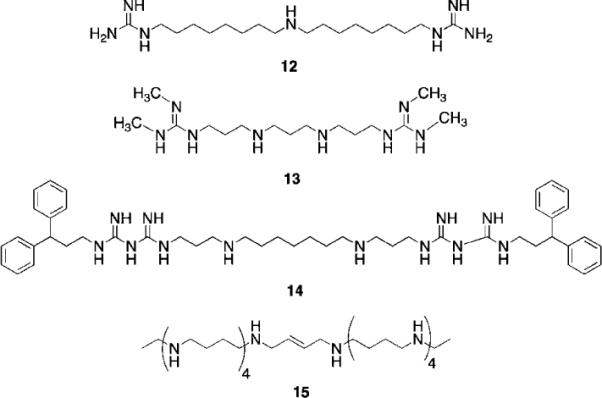

LSD1 was identified in part because its C-terminal domain shares significant sequence homology with the polyamine oxidases APAO and SMO.42,62 APAO and SMO are not inhibited by the classical MAO inhibitor pargyline or the diamine oxidase inhibitor semicarbizide,63 but several groups have identified polyamine analogues that act as inhibitors of these 2 polyamine oxidases.62,64–67 It has recently been demonstrated that the polyaminoguanidine guazatine (12, Fig. 7) is a non-competitive inhibitor of maize polyamine oxidase.68 We reported the synthesis of a novel series of related (bis)guanidines and (bis) biguanides69 that are highly effective inhibitors of the parasitic enzyme trypanothione reductase. These compounds act as potent antitrypanosomal agents in vitro, with IC50 values against Trypanosoma brucei as low as 90 nM. Based on their structural similarity to the polyamine oxidase inhibitor 12, we evaluated a small library of these analogues as inhibitors of LSD1. Nine of the 13 compounds tested were found to inhibit recombinant human LSD1 by >50% at 1 μM.59 The two most potent inhibitors, 13 (85.1% inhibition) and 14 (90.9% inhibition), exhibited non-competitive inhibition kinetics, suggesting that they may or may not compete with H3K4me2 at the LSD1 active site. Exposure of HCT116 human colon carcinoma cells to increasing concentrations of 13 and 14 for 48 h produced significant increases in both H3K4me1 and H3K4me2, without affecting global levels of the deactivating mark H3K9me2.59 By contrast, close homologues of 13 and 14 that were found to be poor inhibitors of purified LSD1, were significantly less effective in increasing global levels of H3K4me2. Levels of H3K4me3, which is not a substrate for LSD1,43 were not affected by these analogues.

Fig. 7.

Structures of guazatine 12, LSD1 inhibitors 13 and 14, and PG 11144 15.

In cancer cells, H3K4me2 is depleted in the promoters of several epigenetically silenced, and aberrantly DNA-hypermethylated genes that are important in tumorigenesis.40,70,71 We therefore examined whether four members of the secreted frizzle-related protein family (SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP4, and SFRP5)71 and two GATA family transcription factors (GATA4 and GATA5)72 were re-expressed in HCT116 cells following treatment with 1.0 μM 13 or 14. The SFRP1, SFRP4, SFRP5, and GATA5 factors were re-expressed after 48-hour treatment with either compound.59 Compound 14 exhibited greater potency than 13 in this regard. Similar effects of 13 and 14 were observed in RKO colon cancer cells with respect to re-expression of SFRP4 and SFRP5, and global H3K4me2 levels.59 Importantly, compounds 13 and 14 are the first examples of synthetic LSD1 inhibitors that produce epigenetic changes leading to re-expression of tumor suppressor genes. As in the case of HDAC inhibitors, these inhibitor-induced cellular effects have obvious therapeutic potential.

Long chain oligoamines such as PG 11144 (15, Fig. 7) have also been shown to increase H3K4me2 levels, and to promote the re-expression of SFRP 1 and 2 in both HCT116 and RKO colon tumor cell lines. Although this effect appears to be mediated through inhibition of LSD1, 15 acts as a competitive rather than a non-competitive inhibitor of the enzyme.73 In further studies, the re-expression of aberrantly silenced genes by 15 was found to be synergistic with 5-AC. Both 14 and 15 were evaluated in an HCT 116 nude mouse xenograft study; compound 14 alone (10 mg kg−1 daily for 5 days followed by 2 days off) was not effective at limiting tumor growth, but in the presence of 5-AC (2 mg kg−1 for 5 days followed by 2 days off) it nearly completely abolished tumor growth over 38 day period. Compound 15 (10 mg kg−1 twice weekly) produced a 60% reduction in tumor growth alone, and completely abolished tumor growth in combination with 5-AC. Both 14 and 15 produced these effects without any significant changes in animal weight, and both drugs were well tolerated at the doses given.73

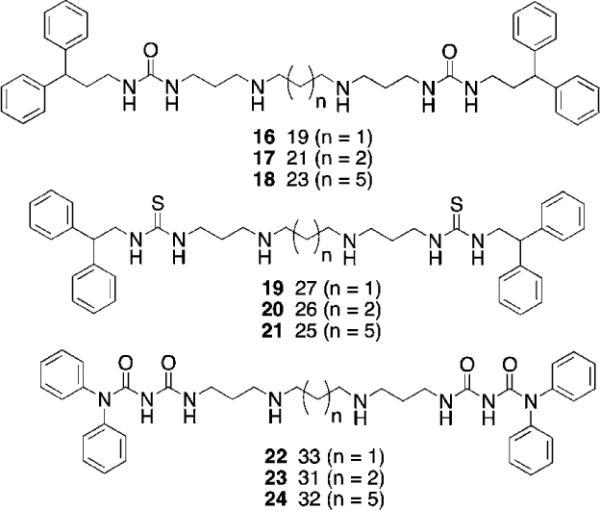

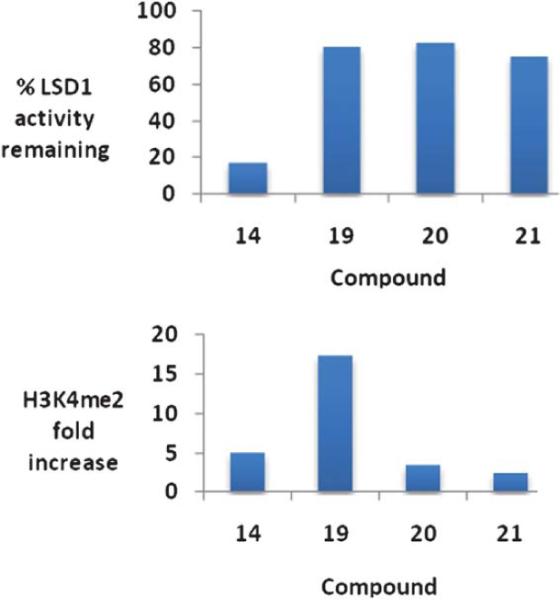

Because of the promising cellular effects of 13 and 14, the synthesis and evaluation of additional analogues was proposed. To access a library of more diverse analogues related to 13 and 14, we adapted our previously published syntheses69 to produce a series of 30 isosteric (bis)alkylureas, (bis)alkylthioureas and (bis)alkylcarbmoylureas.74 These analogues were evaluated for the ability to inhibit LSD1 and to induce increases in global H3K4me2 in vitro. The most active LSD1 inhibitors from this library are shown in Fig. 8. In the urea series, which differed only in the length of the internal carbon chain, compound 16 produced a 7.1% inhibition of LSD1 at 10 μM, while 17 and 18 inhibited the enzyme by 25.4 and 48.5%, respectively. Thus the most potent analogue was the compound with the 3-7-3 carbon backbone structure. By contrast, 19, 20 and 21, which also differed only in the length of the central chain, were essentially equipotent, producing 75.2, 82.9 and 80.5% inhibition at 10 μM. Due to the difficulty of their synthesis, only 3 carbamoylureas were synthesized, differing only in the length of their central chain region. Compounds 22–24 at 10 μM produced 8.5, 73.9 and 30.0% inhibition of LSD1. Interestingly, in this case the compound with the intermediate carbon backbone (3-4-3) was the most effective inhibitor. Additional compounds in the series must be synthesized and evaluated to make any accurate structure–activity correlations, and these studies are underway.

Fig. 8.

Structures of (bis)alkylureas 16–18, (bis)alkylthioureas 19–21 and (bis)alkylcarbamoylureas 22–24.

It is of interest to note that the level of inhibition of recombinant human LSD1 in vitro does not necessarily correlate with cellular increases in H3K4 global methylation, as demonstrated in Fig. 9. As stated above, compounds 19–21 are essentially equally active as LSD1 inhibitors, but have dramatically different effects on global H3K4me2 levels in the Calu-6 lung tumor cell line. Compound 19 produces a dramatic 17.4-fold increase in H3K4me2 levels, compared to 3.5- and 2.4-fold increases for 20 and 21, respectively. Compounds 19–21 did not have a significant effect of the re-expression of GATA4, but 26 and 27 increased the expression of SFRP2 by 2 and 4.5-fold, respectively. Interestingly, 25–27 were relatively non-toxic, with IC50 values in Calu-6 cells greater than 20 μM.74

Fig. 9.

Percent inhibition at 10 μM and the corresponding changes in global H3K4 methylation produced by compounds 14 and 19–21. These data were extracted from original graphs that appeared in ref. 74.

Other small-molecule inhibitors of LSD1

To date, only a few compounds have been published that act as inhibitors of LSD1. It has been shown that classical MAO inhibitors phenelzine and tranylcypromine inactivate nucleosomal demethylation by the recombinant LSD1/CoRest complex, and increase global levels of H3K4me2 in the P19 cell line.58,75 The synthetic peptide substrate analogue aziridinyl-K4H31–21 reversibly inhibited LSD1 with an IC50 of 15.6 μM, while propargyl-K4H31–21 produced time-dependent inactivation with a Ki of 16.6 μM.76 Propargyl-K4H31–21 was later shown to inactivate LSD1 through formation of a covalent adduct with the enzyme-bound flavin cofactor.75,77 Because these substrate analogues are peptide-based, they are not amenable to development as drugs. McCafferty et al. recently described the synthesis of a series of trans-2-arylcyclopropylamine analogues that inhibit LSD1 with Ki values between 188 and 566 μM.78 However, in all but one instance, these analogues were 1–2 orders of magnitude more potent against MAO A and MOA B. Most recently, Ueda and coworkers identified small molecule tranylcypromine derivatives that are selective for LSD1 over MAO-A and MAO-B,79 and Binda et al. described similar tranylcypromine analogues that exhibited partial selectivity between LSD1 and the newly identified histone demethylase LSD2.80

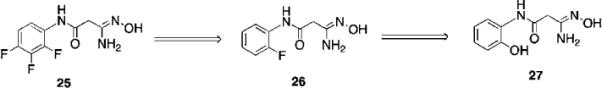

We sought to identify small molecule lead compounds with improved physicochemical properties for use as epigenetic modulators. Thus a virtual screen of the Maybridge Hitfinder 5 compound library employing the Schrödinger suite of modelling programs was undertaken to identify LSD1 inhibitors as potential lead compounds. We selected one of these compounds from a group of several hits, amidoxime 25 (Fig. 10), which had a GlideScore lower than −7.5 kcal mol−1. Compound 25 contained a hydrophilic moiety that appeared to be situated near the FAD cofactor, and a hydrophobic substituent that was bound in the hydrophobic pocket (data not shown). This compound was a weak inhibitor of LSD1 (11.4% at 10 μM), and promoted a 1.6-fold increase in global H3K4me2 levels in the Calu-6 lung tumor cell line. Analysis of 10 related amidoximes led to the identification of 26, which was not an effective inhibitor of LSD1, but produced a 12.4-fold increase in global H3K4 methylation at 10 μM. Expansion of this library to 50 compounds resulted in the discovery of a number of epigenetic modulators that produced increases in H3K4 methylation as high as 3700-fold, including compound 27 (39% inhibition of LSD1 at 10 μM with an accompanying 837-fold increase in global H3K4me2 levels). Under the same conditions, tranylcypromine and pargyline at 10 μM produced an 18.4% and 69.8% inhibition. The full details for the synthesis and evaluation of the amidoxime series of epigenetic modulators is being published in a separate communication.

Fig. 10.

Structures of amidoxime-based epigenetic modulators 25–27.

Conclusions

In contrast to the HDAC field, where multiple inhibitors have advanced into the clinic, the discovery of agents that modulate histone methylation and demethylation in its infancy. However, the processes controlling epigenetic modulation of gene expression are fundamental processes in cellular homeostasis. It follows that aberrations in these processes are important contributing factors in cancer and other diseases. As such, histone methylases and demethylases will soon become drug targets of equal significance to the HDACs. A number of groups have recognized this potential, and lead compounds have already begun to appear in the literature. Epigenetic control via histone methylation/demethylation contributes to the complexity of the process of gene expression, but also provides new targets for the pharmacological modulation of specific genes important in cancer. It appears certain that systematic drug discovery will result in the generation of epigenetic modulators that will become important new therapeutic agents.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH 5RO1 CA149095 (PMW).

Footnotes

This article is part of a MedChemComm web theme issue on epigenetics.

Notes and references

- 1.Marks PA, Miller T, Richon VM. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2003;3:344–351. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks PA, Richon VM, Breslow R, Rifkind RA. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2001;13:477–483. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leuba SH, Karymov MA, Tomschik M, Ramjit R, Smith P, Zlatanova J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:495–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136890100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hargreaves DC, Crabtree GR. Cell Res. 2011;21:396–420. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avvakumov N, Nourani A, Cote J. Mol. Cell. 2011;41:502–514. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Formosa T. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011 DOI: 10.1016/jbbagrm.2011.07.009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amin AD, Vishnoi N, Prochasson P. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.07.008. DOI: 10.1016/jbbagrm.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zlatanova J, Leuba SH. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;331:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00691-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Eugeni EE, Parthun MR, Freitas MA. Chromosoma. 2003;112:77–86. doi: 10.1007/s00412-003-0244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnstone RW. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2002;1:287–299. doi: 10.1038/nrd772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slatkin M. Genetics. 2009;182:845–850. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.102798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chi P, Allis CD, Wang GG. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:457–469. doi: 10.1038/nrc2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woster PM. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2010;45:245–260. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marks PA, Richon VM, Miller T, Kelly WK. Adv. Cancer Res. 2004;91:137–168. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(04)91004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones PA, Baylin SB. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Ghazawi FM, Li Q. Epigenetics: official journal of the DNA Methylation Society. 2010;5:509–515. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stiehl DP, Fath DM, Liang D, Jiang Y, Sang N. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2256–2264. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez R, Zhou MM. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12:659–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang XJ. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2004;26:1076–1087. doi: 10.1002/bies.20104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haberland M, Montgomery RL, Olson EN. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray SG, Ekstrom TJ. Exp. Cell Res. 2001;262:75–83. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taunton J, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. Science. 1996;272:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grozinger CM, Schreiber SL. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.North BJ, Verdin E. GenomeBiology. 2004;5:224. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-5-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esteller M. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16(Spec No 1):R50–59. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel S, Milstein S, Grant S. Oncogene. 2011;30 ePub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinmann H, Ottow E. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2004;39:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemal R, Ravinet A, Molucon-Chabrot C, Bay JO, Guieze R. Bull Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1684/bdc.2011.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kouraklis G, Theocharis S. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:489–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan QC, Headlee D, Acharya M, Sparreboom A, Trepel JB, Ye J, Figg WD, Hwang K, Chung EJ, Murgo A, Melillo G, Elsayed Y, Monga M, Kalnitskiy M, Zwiebel J, Sausville EA. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:3912–3922. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010;48:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seiler N, Dezeure F. Int. J. Biochem. 1990;22:211–218. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(90)90332-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varghese S, Gupta D, Baran T, Jiemjit A, Gore SD, Casero RA, Jr., Woster PM. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:6350–6365. doi: 10.1021/jm0505009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varghese S, Senanayake T, Murray-Stewart T, Doering K, Fraser A, Casero RA, Woster PM. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:2447–2456. doi: 10.1021/jm701384x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Huang L, Zhao W, Rigas B. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2379–2388. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabe Y, Jin L, Contractor R, Gold D, Ruvolo P, Radke S, Xu Y, Tsutusmi-Ishii Y, Miyake K, Miyake N, Kondo S, Ohsaka A, Nagaoka I, Andreeff M, Konopleva M. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1443–1456. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chuthapisith S, Bean BE, Cowley G, Eremin JM, Samphao S, Layfield R, Kerr ID, Wiseman J, El-Sheemy M, Sreenivasan T, Eremin O. Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45:1274–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baylin SB, Ohm JE. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:107–116. doi: 10.1038/nrc1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnstone RW. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2002;1:287–299. doi: 10.1038/nrd772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y. Cell. 2004;119:941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whetstine JR, Nottke A, Lan F, Huarte M, Smolikov S, Chen Z, Spooner E, Li E, Zhang G, Colaiacovo M, Shi Y. Cell. 2006;125:467–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Nature. 2005;436:1103–1106. doi: 10.1038/nature04048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kouzarides T. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2002;12:198–209. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin C, Zhang Y. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:838–849. doi: 10.1038/nrm1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, Reinberg D. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2343–2360. doi: 10.1101/gad.927301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hou H, Yu H. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010;20:739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karytinos A, Forneris F, Profumo A, Ciossani G, Battaglioli E, Binda C, Mattevi A. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:17775–17782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varier RA, Timmers HT. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1815:75–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsukada Y, Zhang Y. Methods. 2006;40:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huarte M, Lan F, Kim T, Vaughn MW, Zaratiegui M, Martienssen RA, Buratowski S, Shi Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:21662–21670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703897200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liang G, Klose RJ, Gardner KE, Zhang Y. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:243–245. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Secombe J, Li L, Carlos L, Eisenman RN. Genes Dev. 2007;21:537–551. doi: 10.1101/gad.1523007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang J, Sengupta R, Espejo AB, Lee MG, Dorsey JA, Richter M, Opravil S, Shiekhattar R, Bedford MT, Jenuwein T, Berger SL. Nature. 2007;449:105–108. doi: 10.1038/nature06092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liang G, Lin JC, Wei V, Yoo C, Cheng JC, Nguyen CT, Weisenberger DJ, Egger G, Takai D, Gonzales FA, Jones PA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:7357–7362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401866101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Myers FA, Thorne AW, Crane-Robinson C, Kouzarides T. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:73–77. doi: 10.1038/ncb1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee MG, Wynder C, Schmidt DM, McCafferty DG, Shiekhattar R. Chem. Biol. 2006;13:563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang Y, Greene E, Murray Stewart T, Goodwin AC, Baylin SB, Woster PM, Casero RA., Jr. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:8023–8028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700720104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lachner M, O'Sullivan RJ, Jenuwein T. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:2117–2124. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stavropoulos P, Hoelz A. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2007;11:809–820. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Y, Murray-Stewart T, Devereux W, Hacker A, Frydman B, Woster PM, Casero RA., Jr. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;304:605–611. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00636-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Y, Devereux W, Woster PM, Stewart TM, Hacker A, Casero RA., Jr Cancer Res. 2001;61:5370–5373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferioli ME, Berselli D, Caimi S. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004;201:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Casara P, Jund K, Bey P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:1891–1894. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bellelli A, Cavallo S, Nicolini L, Cervelli M, Bianchi M, Mariottini P, Zelli M, Federico R. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;322:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Y, Hacker A, Murray-Stewart T, Frydman B, Valasinas A, Fraser AV, Woster PM, Casero RA., Jr. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2005;56:83–90. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0936-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cona A, Manetti F, Leone R, Corelli F, Tavladoraki P, Polticelli F, Botta M. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3426–3435. doi: 10.1021/bi036152z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bi X, Lopez C, Bacchi CJ, Rattendi D, Woster PM. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3229–3232. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McGarvey KM, Fahrner JA, Greene E, Martens J, Jenuwein T, Baylin SB. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3541–3549. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fahrner JA, Eguchi S, Herman JG, Baylin SB. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7213–7218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Akiyama Y, Watkins N, Suzuki H, Jair KW, van Engeland M, Esteller M, Sakai H, Ren CY, Yuasa Y, Herman JG, Baylin SB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:8429–8439. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8429-8439.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang Y, Murray-Stewart T, Wu Y, Baylin SB, Marton LJ, Woster PM, Casero J, R.A. Cancer Chemo. Pharmacol. 2009;15:7217–7228. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharma SK, Wu Y, Steinbergs N, Crowley ML, Hanson AS, Casero RA, Woster PM. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:5197–5212. doi: 10.1021/jm100217a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmidt DM, McCafferty DG. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4408–4416. doi: 10.1021/bi0618621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Culhane JC, Szewczuk LM, Liu X, Da G, Marmorstein R, Cole PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4536–4537. doi: 10.1021/ja0602748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Szewczuk LM, Culhane JC, Yang M, Majumdar A, Yu H, Cole PA. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6892–6902. doi: 10.1021/bi700414b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shao GB, Ding HM, Gong AH. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.: Anim. 2008;44:115–120. doi: 10.1007/s11626-008-9082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ueda R, Suzuki T, Mino K, Tsumoto H, Nakagawa H, Hasegawa M, Sasaki R, Mizukami T, Miyata N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17536–17537. doi: 10.1021/ja907055q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Binda C, Valente S, Romanenghi M, Pilotto S, Cirilli R, Karytinos A, Ciossani G, Botrugno OA, Forneris F, Tardugno M, Edmondson DE, Minucci S, Mattevi A, Mai A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132 doi: 10.1021/ja101557k. ePub 10.1021/ja101557k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]