Abstract

Cambrian lobopodians are important for understanding the evolution of arthropods, but despite their soft-bodied preservation, the organization of the cephalic region remains obscure. Here we describe new material of the early Cambrian lobopodian Onychodictyon ferox from southern China, which reveals hitherto unknown head structures. These include a proboscis with a terminal mouth, an anterior arcuate sclerite, a pair of ocellus-like eyes and branched, antenniform appendages associated with this ocular segment. These findings, combined with a comparison with other lobopodians, suggest that the head of the last common ancestor of fossil lobopodians and extant panarthropods comprized a single ocular segment with a proboscis and terminal mouth. The lack of specialized mouthparts in O. ferox and the involvement of non-homologous mouthparts in onychophorans, tardigrades and arthropods argue against a common origin of definitive mouth openings among panarthropods, whereas the embryonic stomodaeum might well be homologous at least in Onychophora and Arthropoda.

Lobopodians include stem-group arthropods and panarthropods, and date back to the early Cambrian. Ou et al. describe specimens of the early Cambrian lobopodian Onychodictyon ferox, revealing new head structures such as modified appendages, eyes, a terminal mouth and a sucking pharynx.

Lobopodians include stem-group arthropods and panarthropods, and date back to the early Cambrian. Ou et al. describe specimens of the early Cambrian lobopodian Onychodictyon ferox, revealing new head structures such as modified appendages, eyes, a terminal mouth and a sucking pharynx.

The great diversity of arthropod body plans is reflected by the manifold architecture of their heads. This diversity might have its origins in the early Cambrian or even Pre-Cambrian periods1,2,3, when the three major groups of Panarthropoda diverged: Onychophora (velvet worms), Tardigrada (water bears) and Arthropoda (spiders, centipedes, insects and alike). The trunk anatomy of the last common ancestor of panarthropods most likely resembled that of fossil lobopodians, which share with extant onychophorans and tardigrades a homonomous body segmentation, a soft cuticle without an exoskeleton, and unjointed limbs called lobopods4,5,6,7. Despite these similarities, the structure and composition of the head among the extant panarthropods are so diverse that it is hard to believe that their heads have a common evolutionary origin. A closer look at the head morphology in fossil lobopodians, thus, might help to unravel the early steps in the diversification of panarthropod heads. So far, however, little is known about the head structure in these ancient animals, mostly because of an incomplete preservation of their anterior ends8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

We therefore analysed exceptionally preserved specimens of the lower Cambrian lobopodian Onychodictyon ferox15 and compared its head anatomy with that in other lobopodians and extant panarthropods. In addition, we examined mouth development in the recent onychophoran Euperipatoides rowelli, which sheds new light on the homology of mouth openings among panarthropods.

Results

Overview

The taxon Lobopodia established by Snodgrass16 most likely comprizes a non-monophyletic assemblage1,4,12,13 of stem-group representatives of Panarthropoda, Onychophora, Tardigrada and Arthropoda. The exact phylogenetic position of O. ferox among non-cycloneuralian ecdysozoans is unresolved11,12,13,14,17.

Emended diagnosis of O. ferox

Armoured lobopodian; anterior end (head region) characterized by a bulbous proboscis, a pair of lateral eyes associated with a pair of dorsolateral, feather-like antenniform appendages and an unpaired arcuate sclerite; mouth terminal, succeeded by a buccal tube leading into a pharyngeal bulb followed by a through-gut; trunk consisting of homonomous segments bearing 12 pairs of unjointed walking limbs (lobopods) with paired claws and 10 pairs of dorsal sclerotized plates; trunk posteriorly merges with last leg pair; body wall and all appendages densely annulated and covered by a thin cuticle (no exoskeleton); and long, slender papillae present on trunk, legs and antenniform appendages.

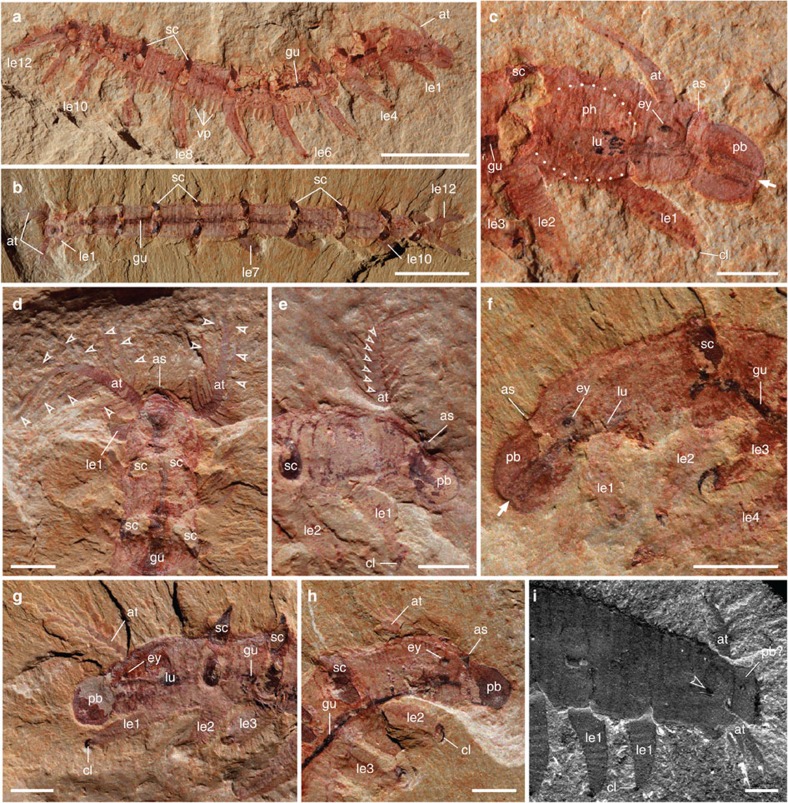

Trunk anatomy in O. ferox

The trunk anatomy of the new material of O. ferox (186 specimens; Supplementary Table S1) corresponds with earlier descriptions15,18 because complete specimens show 10 pairs of sclerotized dorsal plates with thorn-like spines and 12 pairs of annulated lobopods, bearing longitudinal rows of papillae and a pair of sickle-like claws (Figs 1 and 2a–c). The bases of the two posterior-most pairs of limbs are in close proximity, and there is no posterior continuation of the trunk. Numerous finger-like papillae, typically with only the imprints of their bases preserved, are arranged in longitudinal rows along the trunk, and ventrally additional rows of more prominent papillae point downwards (Fig. 2a). In contrast to previous descriptions15,18 of a ‘short, rounded' head15, our specimens show a more complex anatomy of the anterior end than hitherto realized (Figs 1 and 2a–h; Supplementary Figs S1–S6).

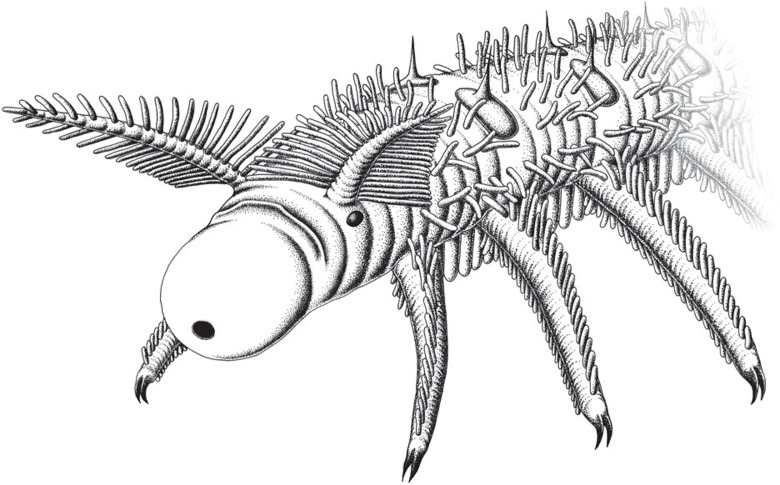

Figure 1. Anterior body region of the lobopodian O. ferox.

Amongst the most conspicuous structures are the feathery, antenniform appendages, the proboscis with a terminal mouth and the ocellus-like eye at the basis of each antenniform appendage.

Figure 2. Anatomy of the lobopodians O. ferox and A. pedunculata.

(a–h) O. ferox. (a) Laterally compressed specimen ELEL-SJ101888A; anterior is right. (b) Dorsoventrally compressed specimen ELEL-EJ100329A; anterior is left. (c) Close-up of anterior end in a showing head structures and outline of bulbous pharynx (dotted lines). Arrow points to mouth. (d) Close-up of anterior end in b showing a pair of branched antenniform appendages (branches indicated by arrowheads). (e) Specimen ELEL-SJ102011A showing left antenniform appendage with branches. Note annulations of antenniform appendage (arrowheads) and claws on first walking lobopod. (f) Specimen ELEL-SJ100307B showing an eye with a lens-like structure. Arrow indicates mouth. (g,h) Specimens ELEL-SJ100635 and ELEL-SJ100546A showing anterior anatomy, notably proboscis, eye and branched antenniform appendages. (i) Anterior end of A. pedunculata. Note branched antenniform appendages, eye-like structure (arrowhead) and putative proboscis delineated from the rest of the body. as, arcuate sclerite; at, antenniform appendage; bt, buccal tube; cl, claw; ey, eye; gu, gut; le1–le12, walking lobopods 1–12; lu, pharyngeal lumen; pb, proboscis; ph, pharynx; sc, sclerotized plate; vp, ventral papillae. Scale bars, 1 cm in a and b; 2 mm in c–i.

Head anatomy in O. ferox

The new material reveals that the anterior-most portion of the head comprizes a bulbous proboscis, delineated from the rest of the body by a circumferential constriction. A terminal mouth extends into a straight buccal tube (Figs 1 and 2c; Supplementary Figs S1–S3). In laterally preserved specimens, the anterior end can be seen to be bent slightly ventrally (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Figs S1–S4). This accounts for why the proboscis is not seen in specimens preserved in other aspects (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Table S1) and, hence, remained undetected in previous studies15,18. The proboscis is succeeded by the first body segment, which bears a pair of eyes and antenniform appendages. The eyes are represented by carbonaceous remains of simple, ocellus-like structures situated dorsolaterally on the head. Adjacent to these is a pair of annulated antenniform appendages with numerous branches (Figs 1 and 2c–h; Supplementary Figs S1–S5).

Another prominent feature of the head is a structure posterior to the proboscis, belonging to the first body segment and referred to as the ‘arcuate sclerite' (Figs 1 and 2c–f; Supplementary Figs S1, S6). In contrast to the first and the remaining body segments, sclerotized structures of any sort are not evident in the second segment, which bears the first pair of walking lobopods (Figs. 1 and 2c–h; Supplementary Figs S1–S4). A conspicuous feature of this second segment is an internal bulbous structure with an expanded lumen and dark contents, which anteriorly joins the buccal tube and posteriorly the alimentary canal (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Fig. S1). We regard this bulbous structure as a suctorial pharynx on account of its resemblance in position and shape to the pharynx of extant tardigrades and onychophorans19,20 (Supplementary Fig. S7).

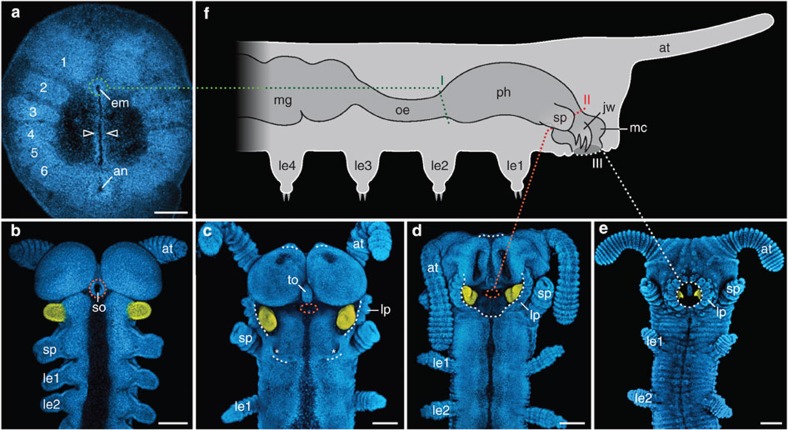

Mouth development in Onychophora

During embryonic development of the onychophoran E. rowelli, three consecutive mouth openings arise ventrally (Fig. 3a–f). The first mouth occurs anteriorly in the embryonic disc, when the lateral lips of the blastopore close by amphystomy (Fig. 3a). During further development, the ectoderm surrounding this first mouth opening invaginates and forms the second mouth, that is, the stomodaeum, the walls of which eventually give rise to the adult pharynx21,22,23 (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. S7). During stomodaeum development, the orifice of the first (blastoporal) mouth is internalized and, thus, corresponds to the posterior border of the presumptive pharynx (Fig. 3a). The stomodaeum is initially located at the border between the first and second body segments (Fig. 3b). As development proceeds, large ectodermal areas surrounding the stomodaeum sink into the embryo—a process by which the stomodaeum and the anlagen of jaws and tongue are incorporated into the newly formed mouth cavity (Fig. 3c–f). This cavity persists in adults and opens to the exterior via the definitive (third) mouth opening (Fig. 3e; Supplementary Fig. S7). During ontogeny, this mouth opening is formed by an accumulation of lips that originate from the antennal, jaw and slime papilla segments and aggregate around the mouth (Fig. 3c–e). At the end of embryogenesis, the stomodaeum disappears completely within the definitive mouth cavity, and its initial opening corresponds to the anterior border of the presumptive pharynx (Fig. 3d–f; Supplementary Fig. S7).

Figure 3. Mouth development in the onychophoran E. rowelli.

Note that three consecutive mouth openings arise during onychophoran ontogeny (indicated by green, red and white dotted lines, respectively). (a–e) Confocal micrographs of embryos at subsequent developmental stages52 in ventral view, labelled with the DNA-marker Hoechst as described previously60. Anterior is up. Presumptive jaws are coloured artificially in yellow. (a) Embryonic disc of a late stage 1 embryo. Note the first embryonic mouth (em) arising at the anterior end of the slit-like blastopore. Developing segments are numbered. Arrowheads point to closing blastoporal lips. (b) Anterior end of an early stage 4 embryo. Note the position of the stomodaeum (second mouth) at the posterior border of the antennal segment. (c) Anterior end of a late stage 4 embryo. Note the beginning formation of lips that originate from three different segments (white dotted lines). Asterisks indicate openings of presumptive salivary glands. (d) Anterior end of a stage 5 embryo showing the formation of the definitive (third) mouth. Note that the stomodaeum and the anlagen of jaws and tongue are incorporated into the mouth cavity. (e) Anterior end of a stage 7 embryo. Mouth development is completed and lips surround the circular mouth opening. (f) Diagram of an adult onychophoran illustrating regions of digestive tract that correspond to the three consecutive embryonic mouth openings (dotted lines with Roman numerals I–III). Dorsal is up, anterior is right. an, developing anus; at, antenna; em, first embryonic mouth (derivative of the blastopore); jw, jaw; le1–le4, legs 1–4; lp, developing lips; mc, mouth cavity; mg, midgut; oe, oesophagus; ph, pharynx; so, stomodaeum; sp, slime papilla; to, presumptive tongue. Scale bars, 200 μm in a–e.

Discussion

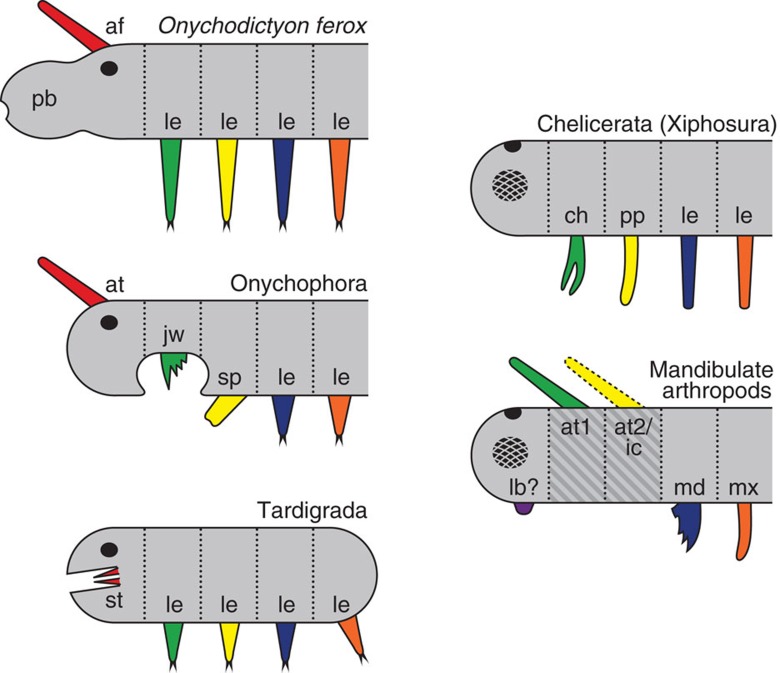

According to our findings, the paired antenniform appendages of O. ferox, which are associated with the ocular segment, differ from walking lobopods in three respects: (i) they lack terminal claws, (ii) they bear on either side slender projections decreasing in length distally and (iii) they have bases that insert dorsolaterally on the ocular segment rather than ventrolaterally. Before this discovery, the identity of the anterior-most pair of appendages in O. ferox has remained controversial15,17,18,24. An original identification of putative antennae15 was then rejected11,18,25, but subsequently gained some support17. In addition, the anterior-most pair of clawed lobopods were reinterpreted as a pair of modified cephalic appendages18,24. Our material, however, shows that the first pair of lobopods do not differ from succeeding pairs and so form a homonomous series of ventral annulated limbs equipped with longitudinal rows of papillae and terminal claws. The pair of antenniform cephalic appendages identified here, thus, lie in front of the first pair of clawed lobopods. Given their location on the ocular segment, we suggest that these appendages are homologous to the branched anterior appendages of Aysheaia pedunculata9 (Fig. 2i), the first pair of unbranched antenniform appendages of Antennacanthopodia gracilis26, and to the antennae of extant onychophorans23.

In contrast, the homology of these appendages with segmental limbs of crown-group arthropods is more difficult to establish because of many divergent views on the composition and evolution of the arthropod heads5,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. The equivalents of the first pair of appendages might have been lost in extant arthropods because the anterior-most segment in these animals does not show typical modified limbs33,34,37. Alternatively, the so-called ‘labrum' might be a possible homologue or remnant of this pair of limbs32,38,39. However, this view depends on whether the labrum belongs to the first/ocular segment32,33, or to the third/intercalary segment27,28, or whether it is an independent morphological structure/unit/segment anterior to the eye region29,40. Thus, even among the insect species studied, the segmental identity of the labrum is uncertain, not to mention the homology of various structures referred to as a ‘labrum' throughout the four major arthropod groups (chelicerates, myriapods, crustaceans and insects). In fact, some authors suggest that a true labrum only exists in the in-group crustacean taxon Labrophora30,31. We therefore caution against an uncritical homologization of structures identified as a ‘labrum' among crown-group arthropods.

Likewise, the homology of various cephalic appendages across stem-group and crown-group arthropods is controversial. Major inconsistency concerns the so-called ‘great appendages', which have been assigned to the first32, second5,33,34,35 or third cephalic segments36. One of the reasons for the lack of consensus might be insufficient information on head development from fossils. As is well known from work on living arthropods, segmental identities of anterior appendages are difficult to establish without analysing gene-expression patterns and details of embryology41,42. It seems therefore premature to speculate on the homology of ‘great appendages' across panarthropods with complex, composite heads. In contrast, the early cephalization events of stem-group panarthropods might be easier to understand, given the low complexity of their ‘heads'. According to our findings, the anterior-most, antenniform appendages of O. ferox are homologous to the antennae of onychophorans23,37,38,39. Thus, they can be regarded as ‘primary antennae', whereas the equivalents of ‘secondary antennae' (=first antennae of the mandibulate taxa)33 in O. ferox are unmodified walking limbs.

Ocellus-like visual organs similar to those reported here from specimens of O. ferox are found in the coeval lobopodians Miraluolishania haikouensis43, Luolishania longicruris12 and A. gracilis26, as well as extant Onychophora44. In addition, ocellus-like structures occur in A. pedunculata9 (Fig. 2i) and extant Tardigrada45. Evidence from the innervation pattern44 and opsins46 in Onychophora suggests that simple, ocellus-like eyes are an ancestral feature of Panarthropoda, whereas compound eyes evolved in the arthropod lineage. This hypothesis receives support from the organization of visual organs in fossil lobopodians, given their non-monophyly and phylogenetic position near the basis of the panarthropod tree2,6,12,13. We therefore suggest that the eyes of fossil lobopodians and extant onychophorans are homologous and that ocelli were the only type of visual organs present in their last common ancestor. These visual organs might have persisted as median ocelli in extant arthropods44, whereas subsequent multiplication and modification of these structures gave rise to the ommatidia of compound eyes47,48.

The position and near-vertical orientation of the arcuate sclerite in O. ferox suggest that this structure might have served as an attachment site for the proboscis musculature. To date, this sclerite has not been reported from other lobopodians and might represent an apomorphy of O. ferox. Notably, re-examination of the Burgess Shale lobopodian A. pedunculata reveals what may be a bulbous proboscis, delineated by a constriction (Fig. 2i; Delle Cave and Simonetta8 but see Whittington9 for an opposed view). Taking into account that lobopodians might be a paraphyletic grade1,4,6,12,13 and that A. pedunculata is one of the earliest-branching lobopodians6,12, we suggest that a non-segmental proboscis with a terminal mouth was present in the last common ancestor of Cambrian lobopodians and extant panarthropods. Whether this structure is homologous to the proboscis of pycnogonids49,50 or to the introvert of some cycloneuralians51, which also show a terminal mouth, is open for discussion.

Irrespective of this controversy, attempts have been made to homologize the terminal mouth of fossil lobopodians (and cycloneuralians) with the ventral mouth of onychophorans, suggesting that the mouth opening simply migrated to a ventral position in the onychophoran ancestor38. However, we have shown here that three different mouth openings arise during onychophoran embryogenesis. This begs the question, which one of these openings can be homologized with the mouths found in other panarthropods. Our data show that the adult onychophoran mouth has a unique ontogenetic fate, as it involves structures that are not found in other animal groups, including lips, tongue and jaws. The lips surrounding the definitive mouth opening originate from the antennal, jaw and slime papilla segments21,22,52. Accordingly, the onychophoran mouth is derived from three anterior-most body segments, whereas the mouth of O. ferox is proboscideal and, therefore, belongs to a pre-antennal, non-segmental body region (Fig. 4). Our data further revealed no appendage-derived mouthparts in O. ferox, whereas onychophorans show a pair of jaws enclosed within a mouth cavity. The jaws are modified limbs of the second body segment, equivalent to the first pair of walking lobopods in O. ferox. On this basis, neither the position (segmental identity) of the adult mouth nor the composition of its cavity indicates homology of mouth apparatuses in onychophorans and O. ferox.

Figure 4. Alignment and homology of anterior appendages in the lobopodian O. ferox and among extant panarthropods.

Homologous appendages are depicted by corresponding colour. Vertical dotted lines indicate segmental borders. Black and checked ovals represent ocelli and compound eyes, respectively. Alignment of head segments in tardigrades is based on the assumption of serial homology of the stylet with distal leg portions20. Note that segmental identity and homology of the arthropod labrum is discussed controversially30,31,33,40. Dark-grey hatched area in the diagram on mandibulate arthropods indicates segments that do not contribute to adult mouth formation. Note that non-homologous segments and structures are involved in adult mouth apparatuses in O. ferox and different groups of extant panarthropods. af, antenniform appendage; at, antenna; at1, first antenna; at2, second antenna (indicated by a dotted line, as it occurs only in crustaceans); ch, chelicera; ic, intercalary segment (limbless in myriapods and hexapods); jw, jaw; lb, labrum (question mark highlights the uncertain segmental identity and homology of this structure); le, walking limbs/lobopods; md, mandible; mx, maxilla; pb, proboscis; pp, pedipalp; sp, slime papilla; st, stylet.

Likewise, owing to the differing positions of the openings and the involvement of different segments, neither the onychophoran nor the O. ferox mouths appear to be homologous with the mouth apparatuses in arthropods and tardigrades (Fig. 4). Various arthropods, including pycnogonids, xiphosurans and entomostracan crustaceans, show no specialized mouth chambers with internalized limbs, whereas in myriapods, hexapods and malacostracan crustaceans, the mouth chamber is formed by several pairs of modified appendages, including the mandibles and the maxillae33,53 (the latter are enclosed within an additional pouch of the head capsule in entognathan hexapods). In tardigrades, the stylet within the buccal tube might be a derivative of the distal limb portions20, suggesting that at least one pair of segmental appendages has been incorporated into the tardigrade mouth. We therefore interpret the stylet as a derivative of the first pair of segmental appendages, as there is no evidence of any additional segments in the tardigrade head54 (Fig. 4). Thus, neither the stylet nor the mandibles or the maxillae belong to segments, which are homologous to the mouth-bearing segments in onychophorans (Fig. 4). Because neither positional nor structural or any other criteria of homology55,56,57 are satisfied when comparing the adult mouths in O. ferox, onychophorans and other panarthropods, we suggest that they are not homologous but have divergent evolutionary histories in these animal groups.

In contrast, the embryonic stomodaeum might well be homologous at least in Onychophora and Arthropoda. In both taxa, the stomodaeum arises ventrally in the same position, that is, at the border between the first and second body segments (Supplementary Fig. S8), and it gives rise to the corresponding ectodermal foregut structures21,22,23,58. Although these correspondences in position and ontogenetic fate support the homology of the stomodaeum, from this stage onwards, the morphogenetic processes of mouth development differ fundamentally between Onychophora and Arthropoda, and even between different arthropod groups31,49,53,58. Unlike arthropods, the ontogeny of the adult mouth is conserved in Onychophora and, thus, might recapitulate the evolutionary changes that have taken place in the onychophoran lineage. Contrary to the assumption38 of a simple ventral migration of the ancestral mouth, we suggest that the mouth cavity of Onychophora has arisen by an invagination of the ectoderm, surrounding an ancestral mouth opening and subsequent incorporation of the second pair of appendages into this cavity. Along with their migration, these appendages were transformed into jaws—a characteristic feature of recent Onychophora. Thus, the definitive mouth of Onychophora is not equivalent to the terminal mouth of Cambrian lobopodians, including O. ferox, and the transformation between the two mouth types can only be understood by finding transitional forms. We therefore believe that the description of detailed head morphologies, as provided herein for O. ferox, from additional lobopodians will shed more light on the evolution of complexity and diversity of mouth apparatuses among extant panarthropods and their Cambrian relatives.

Methods

Specimens of the lobopodian O. ferox

Specimens of O. ferox (n=186) were collected during 2008–2010 from the Heilinpu (previously Qiongzhusi) Formation (Chengjiang fauna, lower Cambrian, ∼520 Ma), Yunnan, southern China. Among these specimens, 84 are preserved with proboscis, 34 with mouth opening, 44 with buccal tube, 36 with pharyngeal bulb, 32 with eyes, 95 with antennal rachis, 65 with antennal branches and 114 with arcuate sclerite (Supplementary Table. S1). All specimens are reposited in the Early Life Evolution Laboratory, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China.

Specimens of E. rowelli and Macrobiotus sp

Specimens of E. rowelli were obtained and handled as described previously59,60. Tardigrades (Macrobiotus sp.) were obtained from moss samples collected in the Volkspark Großdeuben (Saxony, Germany) and labelled with phalloidin-rhodamine as described for onychophorans60.

Microscopy and image processing

Specimens of the lobopodian O. ferox were photographed using a Canon 5D Mark II digital camera. Details were analysed using a Zeiss Stemi-2000C stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Jena, Germany), equipped with a Canon 450D digital camera. Specimens of the onychophoran E. rowelli and the tardigrade Macrobiotus sp. were analysed with the confocal laser-scanning microscopes Zeiss LSM 510 META (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH) and Leica TCS STED (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Confocal image stacks were processed with Zeiss LSM IMAGE BROWSER v4.0.0.241 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH) and Leica AS AF v2.3.5 (Leica Microsystems). Final panels and diagrams were designed with Adobe (San Jose, CA, USA) Photoshop CS4 and Illustrator CS4.

Author contributions

Q.O. collected and prepared specimens of the lobopodian O. ferox. G.M. handled specimens of the onychophoran E. rowelli and the tardigrade Macrobiotus sp. and prepared the ink reconstruction of O. ferox. G.M. and Q.O. analysed the data and wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and prepared the final manuscript.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Ou, Q. et al. Cambrian lobopodians and extant onychophorans provide new insights into early cephalization in Panarthropoda. Nat. Commun. 3:1261 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2272 (2012).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S8 and Supplementary Table S1

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41102012, Shaanxi-2011JZ006) to D.S. and Q.O., the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2010ZY07, 2011YXL013 and 2012097) to Q.O., and the German Research Foundation (DFG, Ma 4147/3–1) to G.M. G.M. is a Research Group Leader supported by the Emmy Noether Programme of the DFG. We thank the staff of Forests NSW (New South Wales, Australia) for providing collecting permits. We are thankful to Paul Sunnucks and Noel Tait for their help with collecting the onychophorans, to Susann Kauschke and Jan Rüdiger for labelling the tardigrades, to Xingliang Zhang and Jianni Liu for providing the images of A. pedunculata and to Simon Conway Morris for providing helpful comments on the first draft of our manuscript.

References

- Maas A. & Waloszek D. Cambrian derivatives of the early arthropod stem lineage, pentastomids, tardigrades and lobopodians—an ‘Orsten' perspective. Zool. Anz. 240, 451–459 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Edgecombe G. D. Arthropod phylogeny: an overview from the perspectives of morphology, molecular data and the fossil record. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 39, 74–87 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin D. H. et al. The Cambrian conundrum: early divergence and later ecological success in the Early history of animals. Science 334, 1091–1097 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd G. E. Why are arthropods segmented? Evol. Dev. 3, 332–342 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waloszek D., Chen J., Maas A. & Wang X. Early Cambrian arthropods—new insights into arthropod head and structural evolution. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 34, 189–205 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Edgecombe G. D. Palaeontological and molecular evidence linking arthropods, onychophorans, and other Ecdysozoa. Evo. Edu. Outreach 2, 178–190 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Maas A., Mayer G., Kristensen R. M. & Waloszek D. A Cambrian micro-lobopodian and the evolution of arthropod locomotion and reproduction. Chin. Sci. Bull. 52, 3385–3392 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Delle Cave L. & Simonetta A. M. Notes on the morphology and taxonomic position of Aysheaia (Onychophora?) and of Skania (undetermined phylum). Monitore Zoologico Italiano 9, 67–81 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- Whittington H. B. The lobopod animal Aysheaia pedunculata Walcott, middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 284, 165–197 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Dzik J. & Krumbiegel G. The oldest ‘onychophoran' Xenusion: a link connecting phyla? Lethaia 22, 169–181 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Bergström J. & Hou X. G. Cambrian Onychophora or xenusians. Zool. Anz. 240, 237–245 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Hou X. & Bergström J. Morphology of Luolishania longicruris (lower Cambrian, Chengjiang Lagerstätte, SW China) and the phylogenetic relationships within lobopodians. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 38, 271–291 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. et al. An armoured Cambrian lobopodian from China with arthropod-like appendages. Nature 470, 526–530 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzik J. The xenusian-to-anomalocaridid transition within the lobopodians. Boll. Soc. Paleontol. Ital. 50, 65–74 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ramsköld L. & Hou X. New early Cambrian animal and onychophoran affinities of enigmatic metazoans. Nature 351, 225–228 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass R. E. Evolution of the Annelida, Onychophora and Arthropoda. Smithson. Misc. Coll. 97, 1–159 (1938). [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Shu D., Han J., Zhang Z. & Zhang X. The lobopod Onychodictyon from the lower Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte revisited. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 53, 285–292 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Ramsköld L. & Chen J. in Arthropod Fossils Phylogeny ed. Edgecombe G. D. 107–150Columbia University Press (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Rhaesa A., Bartolomaeus T., Lemburg C., Ehlers U. & Garey J. R. The position of the Arthropoda in the phylogenetic system. J. Morphol. 238, 263–285 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberg K. A., Persson D., Møbjerg N., Wanninger A. & Kristensen R. M. Myoanatomy of the marine tardigrade Halobiotus crispae (Eutardigrada: Hypsibiidae). J. Morphol. 270, 996–1013 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kennel J. Entwicklungsgeschichte von Peripatus edwardsii Blanch. und Peripatus torquatus n. sp. II. Theil. Arb. Zool.-Zootom. Inst. Würzburg 8, 1–93 (1888). [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G., Bartolomaeus T. & Ruhberg H. Ultrastructure of mesoderm in embryos of Opisthopatus roseus (Onychophora, Peripatopsidae): revision of the ‘long germ band' hypothesis for Opisthopatus. J. Morphol. 263, 60–70 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G. & Koch M. Ultrastructure and fate of the nephridial anlagen in the antennal segment of Epiperipatus biolleyi (Onychophora, Peripatidae)—evidence for the onychophoran antennae being modified legs. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 34, 471–480 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Ramsköld L. Homologies in Cambrian Onychophora. Lethaia 25, 443–460 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Hou X.-G. et al. The Cambrian Fossils of Chengjiang, China. The Flowering of Early Animal Life Blackwell Publishing (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Ou Q. et al. A rare onychophoran-like lobopodian from the lower Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte, Southwest China, and its phylogenetic implications. J. Paleontol. 85, 587–594 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Haas M. S., Brown S. J. & Beeman R. W. Pondering the procephalon: the segmental origin of the labrum. Dev. Genes Evol. 211, 89–95 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan G. S., Williams J. L. D., Posser S. & Bräunig P. Morphological and molecular data argue for the labrum being non-apical, articulated, and the appendage of the intercalary segment in the locust. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 31, 65–76 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbach R. & Technau G. M. Early steps in building the insect brain: neuroblast formation and segmental patterning in the developing brain of different insect species. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 32, 103–123 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siveter D. J., Waloszek D. & Williams M. An early Cambrian phosphatocopid crustacean with three-dimensionally preserved soft parts from Shropshire, England. Special Papers in Palaeontology 70, 9–30 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Maas A. & Waloszek D. Early development of the anterior body region of the grey widow spider Latrodectus geometricus Koch, 1841 (Theridiidae, Araneae). Arthropod Struct. Dev. 38, 401–416 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd G. E. A palaeontological solution to the arthropod head problem. Nature 417, 271–275 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz G. & Edgecombe G. D. The evolution of arthropod heads: reconciling morphological, developmental and palaeontological evidence. Dev. Genes Evol. 216, 395–415 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz G. & Edgecombe G. D. in Crustacea and Arthropod Phylogeny (eds Koenemann S., Jenner R., Vonk R. 139–165CRC Press (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Waloszek D. & Maas A. A new ‘great appendage' arthropod from the lower Cambrian of China and homology of chelicerate chelicerae and raptorial antero-ventral appendages. Lethaia 37, 3–20 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Cotton T. J. & Braddy S. J. The phylogeny of arachnomorph arthropods and the origin of the Chelicerata. Trans. R Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 94, 169–193 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G., Whitington P. M., Sunnucks P. & Pflüger H.-J. A revision of brain composition in Onychophora (velvet worms) suggests that the tritocerebrum evolved in arthropods. BMC Evol. Biol. 10, 255 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson B. J. & Budd G. E. Onychophoran cephalic nerves and their bearing on our understanding of head segmentation and stem-group evolution of Arthropoda. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 29, 197–209 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson B. J., Tait N. N., Budd G. E., Janssen R. & Akam M. Head patterning and Hox gene expression in an onychophoran and its implications for the arthropod head problem. Dev. Genes Evol. 220, 117–122 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posnien N., Bashasab F. & Bucher G. The insect upper lip (labrum) is a nonsegmental appendage-like structure. Evol. Dev. 11, 480–488 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damen W. G. M., Hausdorf M., Seyfarth E. A. & Tautz D. A conserved mode of head segmentation in arthropods revealed by the expression pattern of Hox genes in a spider. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10665–10670 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager M. et al. Homology of arthropod anterior appendages revealed by Hox gene expression in a sea spider. Nature 441, 506–508 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Shu D., Han J. & Zhang Z. A rare lobopod with well-preserved eyes from Chengjiang Lagerstätte and its implications for origin of arthropods. Chin. Sci. Bull. 49, 1063–1071 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G. Structure and development of onychophoran eyes—what is the ancestral visual organ in arthropods? Arthropod Struct. Dev. 35, 231–245 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greven H. Comments on the eyes of tardigrades. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 36, 401–407 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering L. et al. Opsins in Onychophora (velvet worms) suggest a single origin and subsequent diversification of visual pigments in arthropods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 3451–3458 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsch C. & Bitsch J. in Crustaceans and Arthropod Relationships ed. Koenemann S. 81–111CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Book Inc. (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Land M. F. & Nilsson D.-E. Animal Eyes 2nd edn. Oxford University Press (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Vilpoux K. & Waloszek D. Larval development and morphogenesis of the sea spider Pycnogonum litorale (Ström, 1762) and the tagmosis of the body of Pantopoda. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 32, 349–383 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop J. A. & Arango C. P. Pycnogonid affinities: a review. J. Zool. Sys. Evol. Res. 43, 8–21 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen C. Animal Evolution: Interrelationships of the Living Phyla 3rd edn. Oxford University Press (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Walker M. H. & Tait N. N. Studies on embryonic development and the reproductive cycle in ovoviviparous Australian Onychophora (Peripatopsidae). J. Zool. 264, 333–354 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Ungerer P. & Wolff C. External morphology of limb development in the amphipod Orchestia cavimana (Crustacea, Malacostraca, Peracarida). Zoomorphology 124, 89–99 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel W. N. & Goldstein B. Segmental expression of Pax3/7 and Engrailed homologs in tardigrade development. Dev. Genes Evol. 217, 421–433 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remane A. Die Grundlagen des natürlichen Systems, der vergleichenden Anatomie und der Phylogenetik. Theoretische Morphologie und Systematik Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Geest & Portig (1952). [Google Scholar]

- Patterson C. in Problems of phylogenetic reconstruction eds Joysey K. A., Friday A. E. 21–74Academic Press (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Richter S. Homologies in phylogenetic analyses—concept and tests. Theory Biosci. 124, 105–120 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D. T. Embryology and Phylogeny in Annelids and Arthropods Pergamon Press (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G. & Whitington P. M. Velvet worm development links myriapods with chelicerates. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 276, 3571–3579 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G. & Whitington P. M. Neural development in Onychophora (velvet worms) suggests a step-wise evolution of segmentation in the nervous system of Panarthropoda. Dev. Biol. 335, 263–275 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S8 and Supplementary Table S1