Abstract

Objective

B cell depletion therapy (BCDT) ameliorates rheumatoid arthritis by mechanisms that are incompletely understood. Arthritic flare in tumor necrosis factor transgenic (TNF-Tg) mice is associated with efferent lymph node (LN) “collapse,” triggered by B cell translocation into lymphatic spaces and decreased lymphatic drainage. We examined whether BCDT efficacy is associated with restoration of lymphatic drainage due to removal of obstructing nodal B cells.

Methods

We developed contrast-enhancement (CE) MRI imaging, near-infrared indocyanine green (NIR-ICG) imaging, and intravital immunofluorescent imaging to longitudinally assess synovitis, lymphatic flow, and cell migration in lymphatic vessels in TNF-Tg mice. We tested to see if BCDT efficacy is associated with restoration of lymphatic draining and cell egress from arthritic joints.

Results

Unlike active lymphatics to normal and pre-arthritic knees, afferent lymphatic vessels to collapsed LNs in inflamed knees do not pulse. Intravital immunofluorescent imaging demonstrated that CD11b+ monocytes/macrophages in lymphatic vessels afferent to expanding LN travel at high velocity (186 ± 37 micrometer/sec), while these cells are stationary in lymphatic vessels afferent to collapsed PLN. BCDT of flaring TNF-Tg mice significantly decreased knee synovial volume by 50% from the baseline level, and significantly increased lymphatic clearance versus placebo (p<0.05). This increased lymphatic drainage restored macrophages egress from inflamed joints without recovery of the lymphatic pulse.

Conclusion

These results support a novel mechanism in which BCDT of flaring joints lessens inflammation by increasing lymphatic drainage and subsequent migration of cells and cytokines from the synovial space.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), Flare, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), B cells in Inflamed Lymph Nodes (B-in), Lymphatic Pulse

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a prevalent debilitating inflammatory joint disease characterized by exacerbations and remissions, whose etiology remains poorly understood (1). Reports that the inflammatory-erosive arthritis phenotype of tumor necrosis factor-transgenic (TNF-Tg) mice closely mimics human RA (2), and the remarkable clinical success of anti-TNF therapy for this disease (3-6), underscore a critical role for this pleiotropic cytokine in disease pathogenesis. More recently, the success of anti-CD20 (rituximab) B cell depletion therapy (BCDT) in RA suggests that B cells can also modulate synovial inflammation and matrix destruction (7-11). Interestingly, although a major rationale for BCDT is elimination of autoantibodies that are diagnostic for RA progression (i.e. rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA)) (12, 13), the efficacy of anti-CD20 in patients is not always associated with significant changes in autoantibody or total immunoglobulin levels (8, 14), and seronegative patients are responsive to anti-CD20 treatment (11, 15). Collectively, these findings support a non-antibody-mediated contribution of B cells to RA pathogenesis. However, the mechanism by which B cells trigger arthritic “flare,” as defined by the sudden exacerbation of synovitis and focal erosion in select joints during chronic-systemic inflammatory disease; and how BCDT ameliorates this condition, primarily by the indirect removal of macrophages from the inflamed synovium (16), remain enigmatic.

Our approach to understand arthritic flare in TNF-Tg mice (3647 line in C57BL/6 background) has focused on longitudinal imaging studies using contrast enhanced (CE) MRI, near-infrared indocyanine green (NIR-ICG)-imaging and in vivo micro-CT, in order to visualize and quantify changes in soft tissues, lymphatic flow, and bone during inflammatory-erosive arthritis (17-23). These studies revealed that development of ankle and knee arthritis in TNF-Tg mice proceeds by two distinct mechanisms. Ankle arthritis begins as a symmetric tenosynovitis in the hindpaws characterized by macrophage and granulocyte infiltration of the tendon sheaths (24). This tenosynovitis rapidly progresses to an erosive pannus-like tissue that invades the mineralized cartilage and bone of the adjacent small bones in the foot. Interestingly, the pannus tissue is primarily comprised of macrophages and granulocytes (>90%), and very few lymphocytes (<1%) (24, 25). Conversely, the hematopoietic rich marrow that develops subchondral to the erosive pannus tissue contains large numbers of B cells (24, 25). This TNF-induced mechanism of arthritis in ankle joints is largely B cell-independent, as it has been shown that lymphocyte deficient TNF-Tg mice (TNFδARE × RAG1−/−) displayed full clinical and histopathological signs of chronic destructive inflammatory arthritis in their ankle joints (26). We have confirmed this finding with TNF-Tg × μMT−/− and TNF-Tg × RAG1−/− mice, and have found that anti-CD20 therapy does not ameliorate inflammatory-erosive arthritis in the ankles of TNF-Tg mice (Figure 1J, Supplemental Figure 1).

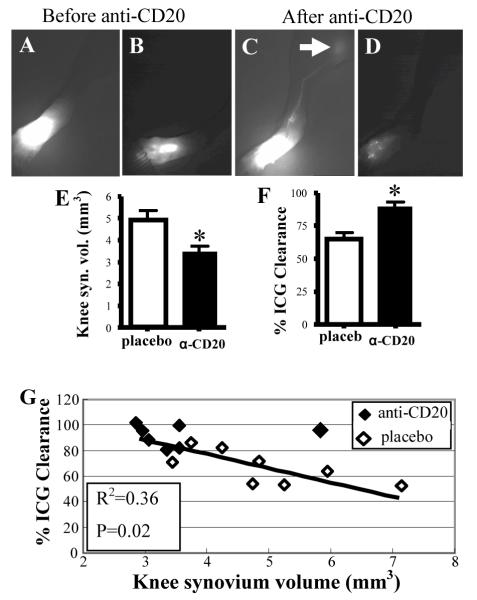

Figure 1.

LNCE is enhanced during effective anti-CD20 therapy for flaring knee synovitis. Untreated TNF-Tg mice with expanding (Exp) and collapsed (Col) (n=12 knees in each group) were identified by longitudinal CE-MRI (36). A separate Col group was treated with anti-CD20 (a-CD20) (n=11 knees, from 4 TNF-Tg mice with bilateral Col PLN and 3 with unilateral Col PLN). A-F, Longitudinal CE-MRI of a Col PLN (A-C), and reconstructed 3D images of the adjacent synovium (D-F), from a representative flaring knee at baseline (A, D), 2 weeks after treatment (B, E), and 6 weeks after treatment (C, F) are shown. The PLN displayed enhanced LNCE at 2 weeks (red arrow in B). G-J, LNCE (G), LNvol (H), knee synovium volume (I), and ankle synovium volume (J) were quantified in Exp, Col and Col PLN 6 weeks after anti-CD20 treatment. K, Decreased knee flare in B cell deficient TNF-Tg mice. CE-MRI was performed on 6-month-old TNF-Tg (n=8 legs), TNF-Tg × μMT−/− (n=4 legs) and TNF-Tg × RAG1−/− (n=6 legs) mice with equivalent ankle synovitis, and their knee synovial volume is shown. All data represent mean±s.d. *p<0.05 vs. Exp, # p<0.05 vs. Col. $p<0.01 vs. TNF-Tg, &p<0.01 vs. TNF-Tg × μMT−/− .

In contrast to arthritic progression in the hindpaws, arthritic flare in the knee of TNF-Tg mice is often asymmetric, and presents 2 to 4 months after the development of frank ankle arthritis without any detectable changes in immune activation (21, 23). Moreover, longitudinal imaging studies demonstrate a predictable temporal behavior in the draining lymph nodes (LN), which precede the onset of knee flare. Prior to detectable synvovial hyperplasia, the volume of popliteal LN (PLN) expands due to increased lymphangiogenesis, lymphatic fluid accumulation, CD11b+ macrophage infiltration, and the expansion of a unique subset of CD23+/CD21hi B cells in inflamed nodes (B-in) that was defined by a detailed phenotypic analysis (17-22). This expansion is followed by a sudden collapse with B-in translocation from the follicles into the LYVE-1+ lymphatic vessels of the paracortical sinusoids, and a significant decrease in lymphatic drainage as quantified by lymph node capacity (LNcap) and ICG clearance from footpad to draining LNs (17, 21, 23). Significantly, LN collapse occurs in series along the ipsilateral axis, such that the PLN lymphatics are also a biomarker of drainage from the knee to the iliac lymph node (ILN) (23). Taken together with the finding that anti-CD20 treatment of TNF-Tg mice with expanding PLN significantly protects against knee flare (21), we hypothesize that one mechanism of action of BCDT in this setting is B-in removal and “unclogging” of the lymphatic vessels within the LNs to restore inflammatory cell eggress from arthritic joints.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

The 3647 line of TNF-transgenic mice in a C57BL/6 background were originally obtained from Dr. George Kollias (Institute of Immunology, Alexander Fleming Biomedical Sciences Research Center, Vari, Greece). The TNF-Tg mice are maintained as heterozygotes, such that non-transgenic littermates are used as aged-matched wild type (WT) controls. The μMT−/−xTNF-Tg and RAG1−/−xTNF-Tg mice were obtained by cross breeding μMT−/− C57BL/6 background and RAG1−/− C57BL/6 background mice with TNF-Tg mice respectively. The μMT−/− and RAG1−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. All animal studies were performed under protocols approved by the University of Rochester Committee for Animal Resources.

Anti-CD20 treatment

Starting at 3 month of age, TNF-Tg mice received CE-MRI bimonthly, until PLN collapse was detected, at which time they received baseline NIR-ICG imaging. Mouse anti-mouse CD20 mAbs (18B12 IgG2a) or nonspecific placebo IgG2a Abs (2B8) (Biogen Idec, San Diego, CA) were dosed at 10 mg/kg i.p. every 2 wk for 6 wk, with continuous CE-MRI every 2 wk, followed by post treatment NIR-ICG. Cells from PLN and iliac lymph node (ILN) were subjected to flow cytometry. In the group of TNF-Tg mice used for in vivo immuno fluorescent microscope (IFM) imaging of cells in lymphatics, mice received bi-weekly CE-MRI until collapsed PLN is displayed. Then they received anti-CD20 treatment or placebo at the same dosage as described above for only one week. IFM were performed before and after one week of anti-CD20 treatment.

CE-MRI and data analysis

The animals received bilateral CE-MRI of their lower limbs every two weeks to longitudinally assess the inflammatory-erosive arthritis in the ankle and knee joints. Briefly, anesthetized mice were positioned with their knee and ankle inserted into customized knee coil and ankle coil, and MR images were obtained on a 3 Tesla Siemens Trio MRI (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). Amira (TGS Unit, Mercury Computer Systems, San Diego, CA) was used for segmentation and quantification of ankle synovial volume, knee synovial volume, lymph node volume (LNvol), lymph node contrast enhancement (LNCE) and lymph node capacity (LNcap). Based on the level of muscle enhancement, a threshold value corresponding to synovial enhancement was determined accordingly. All voxels above the threshold value within the synovium region that selected manually were labeled as synovium. For segmentation of the LN, regions of interest are manually drawn on a post-contrast three-dimensional stack of images and thresholded based on signal intensity >1500 arbitrary units to define the boundary between the LN and the fat pad surrounding the node. The Tissue Statistics module is used to quantify the volume of synovium and volume of the LN and the value of CE of this tissue and of surrounding muscle. LNcap is defined as the LN CE divided by muscle CE and multiplied by LN volume.

Near-IR Indocyanine Green (NIR-ICG) Lymphatic Imaging

Lymphatic drainage was quantified by ICG-NIR using a Spy1000 system (Novadaq Technologies) as previously described(22). The video outputs of the camera were attached to the network (Axis 241SA video server); the image streams were captured (Security Spy by Ben Bird) as QuickTime movies (Apple Computers). Individual JPEG image sequences were then exported for further analysis with ImageJ. Indocyanine green (Acorn) was dissolved in distilled water at 0.1 μg/μl, and 6 μl of the green solution was injected intradermally into the mouse footpad using a 30-gauge needle. ICG-NIR imaging was performed for 1hr immediately after ICG injection, and again for 5 minutes 24hr later. Sequential images from the movie file were exported, and the ICG fluorescence intensity of the injection site and PLN was determined using Image J software to quantify: % clearance, which is an assessment of ICG washout through the lymphatics and is quantified as the percent difference in ICG signal intensity at the injection site immediately after administration and 24hr later. Lymphatic pulsing frequency was quantified by real time video analysis of NIR-ICG imaging of a region of interest (ROI) of the draining lymphatic vessel afferent to PLN. The signal intensities minus background intensity of representative ROIs is plotted over time.

Intravital Inmmunofluorescent Microscope of lymphatics

Intravital immunofluorescent microscopy was performed on draining lymphatic vessels afferent to PLN by injecting FITC conjugated anti-CD11b, anti-Gr-1, anti-CD19, anti-CD3, or anti-CD45.2 antibody into the footpad of TNF-Tg or WT mice 2hrs prior to imaging. Immediately prior to imaging the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane/O2, hair on the lower limb was removed by hair remover, and Texas red-conjugated dextran beads were subcutaneously injected into the footpad to mark the draining lymphatic vessel. An incision was made behind the knee to expose the PLN and afferent lymphatics to the 5x objective lens of a fluorescent microscope (Axio Imager M1m, Zeiss). Time lapse photographs were taken at 3 frames per second. The moving cells were highlighted red by using “image calculator” of ImageJ, which defines the cells in each frame.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, PLNs were dissected and fixed in 10% neutralized formalin. Tissues were embedded in paraffin wax, and deparaffined sections were quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide and treated for Ag retrieval for 30 min. Sections were then stained with anti-F4/80 Ab (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). For multicolor immunofluorescence microscopy, fresh frozen LNs were cut into 6-μm-thick sections. PLN sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, rehydrated in PBS, and blocked with rat serum, and then incubated with PE-conjugated anti-IgM (clone II/41; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) to stain B cells, anti-LYVE-1 (ab14917, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) together with secondary antibody FITC-anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to stain lymphatic endothelium, goat anti-mouse CXCL13 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) together with FITC conjugated anti-goat IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to stain CXCL13. The B cell analyses were performed using our previously published methods (21), in which a threshold fluorescent signal intensity was set up in the microscope to capture signal only from IgMhi B cells.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from lymph nodes and were analyzed for expression of surface markers with combinations of the following fluorochrome-labeled Abs: APC-Alexa 750 anti-B220 (clone RA3-6B2; eBioscience); PE anti-IgM (clone II/41; eBioscience); Pacific Blue anti-CD21/35 (clone 7E9; BioLegend); PE-Cy7 anti-CD23 (clone B3B4; BioLegend); Samples were run on an LSRII cytometer and analyzed by FlowJo software (BD Pharmingen).

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed t-tests were used to make comparisons with between groups. Correlations between measures were estimated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient and tested for significance using a two-sided t-test test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant and P-values less than 0.01 were considered highly significant. The velocity of the cells in the lymphatic vessel during intravital immunofluorescent imaging session was calculated via blob analysis in ImageJ.

RESULTS

B cell depletion therapy ameliorates knee synovitis and increases lymphatic flow

To demonstrate the effects of BCTD therapy on actively inflamed knees experiencing arthritic flare, TNF-Tg mice with collapsed PLN were identified by longitudinal CE-MRI (23), given 6-weeks of anti-CD20 therapy, and followed by CE-MRI every 2 weeks. Remarkable drug effects were observed on the 2-week CE-MRI as evidenced by the dramatic increase in LN contrast enhancement (LNCE), which is a biomarker of lymphatic drainage, and a concomitant decrease in PLN and synovial volume that continued out to 6-weeks (Figure 1A-F). Quantitative analysis of the CE-MRI data at 6-weeks confirmed these significant effects versus untreated TNF-Tg control knees with expanding and collapsed PLN (Figure 1G-I), and suggests that BCDT allows the Gd-DTPA to occupy the sinus spaces in collapsed PLN that were previously occupied by B cells. To determine if B cells contribute to knee synovitis of TNF-Tg mice, we generated TNF-Tg × μMT−/− and TNF-Tg × RAG1−/− mice and found that knee synovial volume in these B cell-deficient TNF-Tg mice is significantly less than that observed in aged matched TNF-Tg mice at 6-months (Figure 1K), and similar to that of wild type (WT) mice (~2.0mm3) (18). Interestingly, LNCE and knee synovial volume levels following anti-CD20 treatment did not return to that observed in the expanding PLN group without knee flare. This finding relates to the 27% (3 out of 11 flaring knees) “non-responders” who displayed effective peripheral B cell and nodal B-in depletion (Supplemental Figure 2), but remained clogged by IgMhi cells in the lymphatic vessels and displayed low LNCE and increased knee synovitis in CE-MRI (Supplemental Figure 3) Although the detailed phentotypic and functional characteristics of these IgMhi cells are the subject of ongoing study, these results are consistent with the concept that TNF-induced arthritic knee flare is associated with B cell obstruction of lymphatics with subsequent impaired drainage from inflamed joints. The behavior of these non-responders also parallels clinical observations of BCDT in non-responding RA patients (8), and is consistent with the hypothesis that these are not necessarily due to disease heterogeneity, but possibly due to lack of B cell depletion in specific compartments (27).

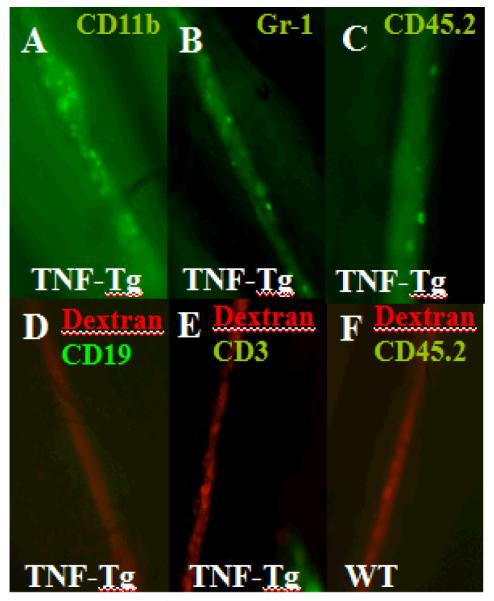

To directly test whether BCDT ameliorates knee synovitis by restoring lymphatic drainage, we performed a prospective study in TNF-Tg mice with recently inflamed knees and collapsed PLN. The mice were randomized to 6-weeks of anti-CD20 or placebo therapy. At the end of the treatment, knees were assessed by CE-MRI and NIR-ICG imaging, and LN were harvested to confirm B cell depletion by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. The results demonstrated that anti-CD20 treatment significantly decreased knee synovial volume by 50% from the 2mm3 baseline level, and increased ICG clearance versus placebo (Figure 2A-F). Moreover, we found a significant negative correlation between ICG clearance and synovial volume (Figure 2G), demonstrating that effective BCDT is accmpanied by augmentation of lymph drainage from inflamed joints.

Figure 2.

Effective BCDT for knee flare increases lymphatic flow in the lower limb. CE-MRI and NIR-ICG imaging was performed to assess synovitis and lymphatic flow in anti-CD20 (n=7 legs, from 3 TNF-Tg mice with bilateral Col PLN and 1 with unilateral Col PLN) vs. placebo (n=8 legs, from 1 mouse with bilateral Col PLN and 6 with unilateral Col PLN) treated TNF-Tg mice. A-D, NIR-ICG imaging of a representative responder before (A, B), and after treatment (C, D) are shown to illustrate the lymphatic clearance of ICG 30mins (A, C) and 24hrs (B, D) after footpad injection. Note the lack of ICG migration in lymphatic vessels to the PLN at 30mins (A), and the large residual amount of ICG in the foot at 24hrs pre-treatment (B). In contrast, there is apparent ICG in efferent lymphatics to the PLN (arrow) at 30mins (C), and scant residual ICG at 24hrs (D) post-treatment. E and F, significant anti-CD20 affects on knee synovitis (E) and improved lymphatic flow (F) are presented as the mean ± SD.* p<0.05 vs. placebo. G, A linear regression of knee synovial volume vs. %ICG clearance data was performed demonstrating a significant negative correlation.

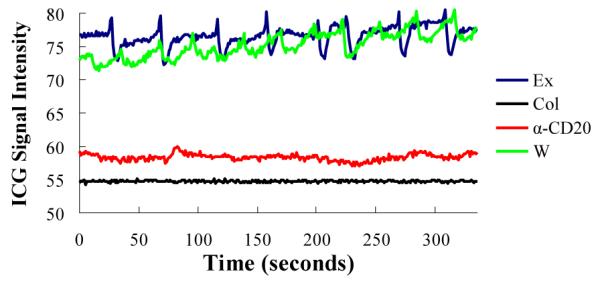

B cell depletion therapy dose not rescue lymphatic pulsing

Upon closer inspection of the real time NIR-ICG imaging sessions, we noticed remarkable differences in the lymphatic pulse between the groups. While lymphatic vessels afferent to expanding PLN in TNF-Tg mice have a similar pulse to that observed in their wild type littermates (about 1.4 beats/min), lymphatic vessels afferent to collapsed PLN do not pulse (Figure 3). Surprisingly, effective BCDT did not restore the lymphatic pulse to increase lymphatic drainage, although it did increase the ICG signal intensity in the lymphatic vessels compared to control (Figure 3). Since lymphatic flow occurs from both “intrinsic” or “active” contractions of lymphatic muscle (pulsing), and “extrinsic” or “passive” lymph pumping from interstitial fluid pressure caused by adjacent tissue movement and/or compression (28), we performed intravital fluorescent microscopy of lymphatic vessels afferent to PLN to evaluate the effects of collapse and BCDT on lymph and cellular flow.

Figure 3.

Anti-CD20 therapy does not restore lymphatic pulsing. Lymphatic pulsing frequency was quantified by real time video analysis of NIR-ICG imaging of a region of interest (ROI) of the draining lymphatic vessel afferent to PLN as previously described(22). Shown are the signal intensities minus background intensity of representative ROIs plotted over time for the four groups studied in which the mean ± SD pulsing frequencies were: WT (WT mice; green line) = 1.4 ± 0.40, Exp (TNF-Tg mice with expanding PLN; blue line) =1.4 ± 0.03, Col (TNF-Tg mice with collapsed PLN; black line) =0 and a-CD20 (TNF-Tg mice with collapsed PLN + 6-weeks of anti-CD20 therapy; red line) = 0 pulses/min. (n≥4 in each group).

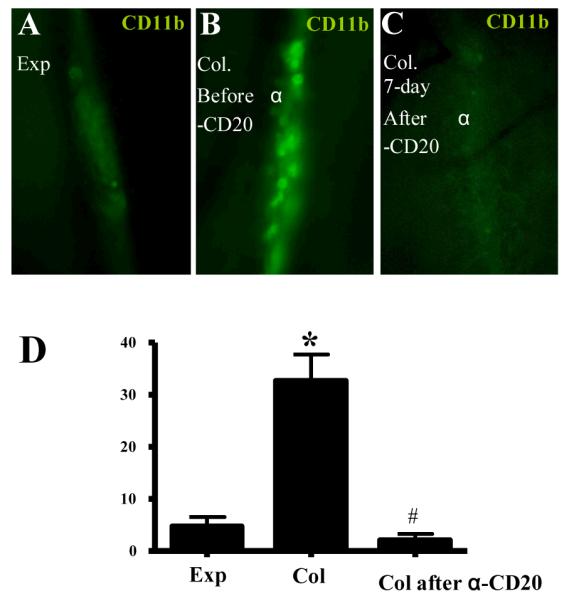

B cell depletion therapy restores CD11b+ cell flow in lymphatic vessels afferent to collapsed PLN

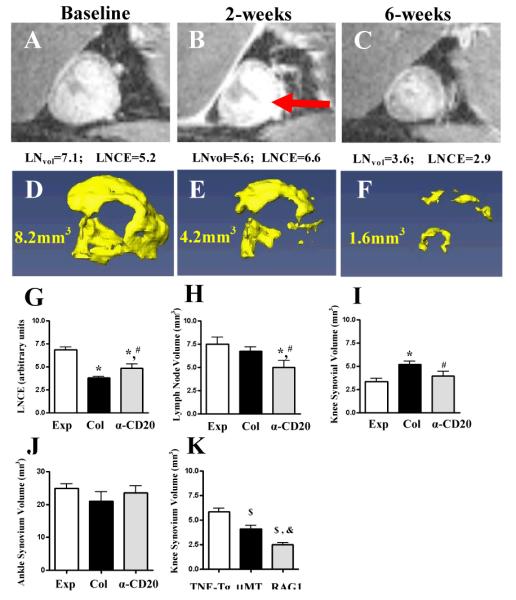

Initially, we determined the cellular phenotype and density, which demonstrated large numbers of CD11b+ and Gr-1+ cells with the size (~20μm diameter) and elliptical morphology of macrophages and granulocytes, possibly dendritic cells as well, but no CD19+ B cells or CD3+ T cells were observed (Figure 4A-D), consistent with the cellular composition of the afferent pannus tissue. Interestingly, most of these cells had no velocity (Supplemental Movie 1) consistent with the absence of a lymphatic pulse and an efferent clog. In contrast, efforts to photograph migrating cells in lymphatic vessels afferent to WT (Figure 4E) and expanding PLN (Figure 5A) by this method failed due to the complete absence of cells in the lymphatic vessels in >90% of the imaging sessions, and high velocity (186 +/− 37 microns/sec) during rare occurrences (Supplemental Movie 2). Quantification of the resident CD11b+ cells confirmed that lymphatic vessels afferent to collapsed PLN have a 7-fold increase versus lymphatic vessels afferent to expanding PLN (Figure 5). Moreover, BCDT restores the migration of CD11b+ cells in lymphatic vessels afferent to collapsed PLN as evidenced by the significant 7-fold decrease in resident cells after treatment (Figure 5D). Since anti-CD20 therapy does not target these macrophages directly, this drug effect is consistent with restoration of flow in efferent lymphatics, which was further substantiated by recovery of extrinsic lymphatic flow as observed by CD11b+ cell migration in response to footpad compression.

Figure 4.

Presence of non-migrating CD11b+ and Gr-1+ cells and absence of B and T cells in draining lymphatic vessels afferent to collapsed PLN. Intravital immunofluorescent microscopy was performed on draining lymphatic vessels afferent to PLN by injecting FITC conjugated anti-CD11b, anti-Gr-1, anti-CD19, anti-CD3, or anti-CD45.2 antibody into the footpad of TNF-Tg or WT mice 2hrs prior to imaging (n=5). Immediately prior to imaging Texas red-conjugated dextran beads were subcutaneously injected into the footpad to mark the draining lymphatic vessel, and an incision was made behind the knee to expose the PLN and afferent lymphatics to the 5x objective lens of a fluorescent microscope (Axio Imager M1m, Zeiss). Immunofluorescent photographs of a representative lymphatic vessel afferent to a collapsed PLN showing the: CD11b+ (A) and Gr-1+ (B) and hematopoietic (CD45.2+) (C) cells. Representative micrographs illustrating the lack of CD19+ (D) and CD3+ (E) cells in lymphatic vessels afferent to collapsed PLN, and absence of hematopoietic (CD45.2+) cells in lymphatic vessels afferent to WT PLN (F).

Figure 5.

Anti-CD20 treatment restores CD11b+ cell flow in lymphatic vessels afferent to Col PLN. A-C, Time lapse intravital immunofluorescent microscopy (1 frame/min) of CD11b+ cells in lymphatic vessels afferent to PLN in TNF-Tg mice was performed as described in Figure 4. Representative micrographs of a lymphatic vessel afferent to an Exp PLN (A), Col PLN (B), and the same Col PLN 7days after anti-CD20 therapy (C), are shown to illustrate the resident CD11b+ cells. D, The number of CD11b+ cells/mm lymphatic vessel/min was quantified during a 40 min imaging session of lymphatic vessels afferent to Exp PLN, or a Col PLN before and after 6-weeks of anti-CD20 therapy. The data are graphed as the mean ± SD. n=5 in each group, * p< 0.01 vs. Exp, # p<0.01 vs. Col.

DISCUSSION

Recently, a consensus statement on the use of rituximab in RA patients has been formulated (29), and the known clinical responses in different compartments of the immune system have been reviewed (30). While this information clearly supports the use of BCDT, it remains largely inconclusive on its precise mechanism of action, which continues to focus on conventional antibody producing and immunomodulatory B cell functions. Although some studies have linked the lack of response to rituximab with persistence of B cells in specific body compartments (27), their location has yet to be defined.

Although it is difficult to draw precise conclusions about the cause and effects of anti-CD20 therapy, here we propose a novel model to explain the role of B cells in arthritic flare, and how BCDT ameliorates synovitis via increased lymphatic flow and macrophage egress from arthritic joints, based on the simplest explanation of our results. Of note is that this model is also in line with emerging concepts of lymphatic changes in metabolic syndrome and chronic inflammatory diseases (31-33). In this model, chronic inflammation and aging collaborate to degenerate and debilitate lymphatic muscle from various mechanisms including atrophy, apoptosis, senescence and attenuated autonomous lymphatic vessel contraction via interference of lymphatic endothelial cell-nitric oxide signaling by inducible nitric oxide synthase-expressing CD11b+/Gr-1+ cells (34). This leads to ipsilateral loss of the lymphatic pulse and LN collapse, and decreased migration of pannus-derived macrophages through the lymphatics. Subsequently, B-in cells in the draining lymph nodes translocates from the follicles to the paracortical sinuses (21, 23), via a yet to be determined mechanism, clogging the afferent lymphatics and triggering arthritic flare. Our demonstration that effective BCDT correlates with: 1) increased lymphatic flow, 2) removal of B cells from lymphatic spaces in draining LN, and 3) restoration of macrophage migration via extrinsic lymph pumping, provides experimental support for this model. However, this model does not exclude the possibility that B cells play a role relatively early on in arthritis pathogenesis that results in joint inflammation; and that removal of these B cells could then reduce inflammation and restore lymph flow directly. As these alternative models involving yet to be identified B cell mediated immunomodulatory changes and/or alterations in lymphatic endothelium are being explored, our initial findings warrant further clinical investigation of the intra-parenchymal changes and vascular flow modulation observed in draining LNs associated with disease activity and during successful BCDT in RA patients (35). Finally, it suggests that non-immunosuppressive therapies aimed at recovering lymphatic flow and cellular egress from flaring joints will ameliorate uncontrolled RA.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Ryan Tierney and Patricia Weber for technical assistance with the histology and CE-MRI respectively. The anti-murine CD20 and IgG2a isotype control monoclonal antibodies were supplied by Biogen Idec (San Diego, CA). This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health PHS awards (E.M.B. is supported by AR53459, AR48697 to L.X., AR56702, AI78907 and AR61307 to E.M.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423(6937):356–61. doi: 10.1038/nature01661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keffer J, Probert L, Cazlaris H, Georgopoulos S, Kaslaris E, Kioussis D, et al. Transgenic mice expressing human tumour necrosis factor: a predictive genetic model of arthritis. EMBO J. 1991;10(13):4025–31. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maini RN, Elliott MJ, Brennan FM, Williams RO, Chu CQ, Paleolog E, et al. Monoclonal anti-TNF alpha antibody as a probe of pathogenesis and therapy of rheumatoid disease. Immunol Rev. 1995;144:195–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Concomitant Therapy Study Group Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1594–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreland LW, Baumgartner SW, Schiff MH, Tindall EA, Fleischmann RM, Weaver AL, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with a recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75)-Fc fusion protein. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(3):141–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707173370301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldmann M, Maini RN. Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award. TNF defined as a therapeutic target for rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Nat Med. 2003;9(10):1245–50. doi: 10.1038/nm939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close DR, et al. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(25):2572–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, Dougados M, Furie RA, Genovese MC, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: Results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):2793–806. doi: 10.1002/art.22025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keystone EC, Emery P, Peterfy CG, Tak PP, Cohen S, Genovese MC, et al. Rituximab inhibits structural joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.085787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emery P, Deodhar A, Rigby WF, Isaacs JD, Combe B, Racewicz AJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of different doses and retreatment of rituximab: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial in patients who are biological naive with active rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate (Study Evaluating Rituximab’s Efficacy in MTX iNadequate rEsponders (SERENE)) Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(9):1629–35. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.119933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tak PP, Rigby WF, Rubbert-Roth A, Peterfy CG, van Vollenhoven RF, Stohl W, et al. Inhibition of joint damage and improved clinical outcomes with rituximab plus methotrexate in early active rheumatoid arthritis: the IMAGE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;70(1):39–46. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.137703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conrad K, Roggenbuck D, Reinhold D, Dorner T. Profiling of rheumatoid arthritis associated autoantibodies. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;9(6):431–5. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee AN, Beck CE, Hall M. Rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: a review. Clin Lab Sci. 2008;21(1):15–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosengren S, Wei N, Kalunian KC, Zvaifler NJ, Kavanaugh A, Boyle DL. Elevated autoantibody content in rheumatoid arthritis synovia with lymphoid aggregates and the effect of rituximab. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(5):R105. doi: 10.1186/ar2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lal P, Su Z, Holweg CT, Silverman GJ, Schwartzman S, Kelman A, et al. Inflammation and autoantibody markers identify rheumatoid arthritis patients with enhanced clinical benefit following rituximab treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(12):3681–91. doi: 10.1002/art.30596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haringman JJ, Gerlag DM, Zwinderman AH, Smeets TJ, Kraan MC, Baeten D, et al. Synovial tissue macrophages: a sensitive biomarker for response to treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(6):834–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.029751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proulx ST, Kwok E, You Z, Beck CA, Shealy DJ, Ritchlin CT, et al. MRI and quantification of draining lymph node function in inflammatory arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1117:106–23. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Proulx ST, Kwok E, You Z, Papuga MO, Beck CA, Shealy DJ, et al. Longitudinal assessment of synovial, lymph node, and bone volumes in inflammatory arthritis in mice by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging and microfocal computed tomography. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(12):4024–4037. doi: 10.1002/art.23128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo R, Zhou Q, Proulx ST, Wood R, Ji RC, Ritchlin CT, et al. Inhibition of lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic drainage via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 blockade increases the severity of inflammation in a mouse model of chronic inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(9):2666–76. doi: 10.1002/art.24764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q, Lu Y, Proulx S, Guo R, Yao Z, Schwarz EM, et al. Increased lymphangiogenesis in joints of mice with inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(6):R118. doi: 10.1186/ar2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Kuzin I, Moshkani S, Proulx ST, Xing L, Skrombolas D, et al. Expanded CD23(+)/CD21(hi) B cells in inflamed lymph nodes are associated with the onset of inflammatory-erosive arthritis in TNF-transgenic mice and are targets of anti-CD20 therapy. J Immunol. 2010;184(11):6142–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Q, Wood R, Schwarz EM, Wang YJ, Xing L. Near-infrared lymphatic imaging demonstrates the dynamics of lymph flow and lymphangiogenesis during the acute versus chronic phases of arthritis in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(7):1881–9. doi: 10.1002/art.27464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Zhou Q, Wood R, Kuzin I, Bottaro A, Ritchlin C, et al. CD23+/CD21hi B cell translocation and ipsilateral lymph node collapse is associated with asymmetric arthritic flare in TNF-Tg mice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(4):R138. doi: 10.1186/ar3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayer S, Redlich K, Korb A, Hermann S, Smolen J, Schett G. Tenosynovitis and osteoclast formation as the initial preclinical changes in a murine model of inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(1):79–88. doi: 10.1002/art.22313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proulx ST, Kwok E, You Z, Papuga MO, Beck CA, Shealy DJ, et al. Elucidating bone marrow edema and myelopoiesis in murine arthritis using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(7):2019–2029. doi: 10.1002/art.23546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kontoyiannis D, Pasparakis M, Pizarro TT, Cominelli F, Kollias G. Impaired on/off regulation of TNF biosynthesis in mice lacking TNF AU-rich elements: implications for joint and gut-associated immunopathologies. Immunity. 1999;10(3):387–98. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boumans MJ, Tak PP. Rituximab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: how does it work? Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(6):134. doi: 10.1186/ar2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muthuchamy M, Zawieja D. Molecular regulation of lymphatic contractility. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:89–99. doi: 10.1196/annals.1413.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buch MH, Smolen JS, Betteridge N, Breedveld FC, Burmester G, Dorner T, et al. Updated consensus statement on the use of rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):909–20. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boumans MJ, Thurlings RM, Gerlag DM, Vos K, Tak PP. Response to rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in different compartments of the immune system. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(11):3187–94. doi: 10.1002/art.30567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chakraborty S, Zawieja S, Wang W, Zawieja DC, Muthuchamy M. Lymphatic system: a vital link between metabolic syndrome and inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1207(Suppl 1):E94–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cueni LN, Detmar M. The lymphatic system in health and disease. Lymphat Res Biol. 2008;6(3-4):109–22. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2008.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buckland J. Experimental arthritis: Targeting joint lymphatic function. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(7):376. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liao S, Cheng G, Conner DA, Huang Y, Kucherlapati RS, Munn LL, et al. Impaired lymphatic contraction associated with immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(46):18784–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116152108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manzo A, Caporali R, Vitolo B, Alessi S, Benaglio F, Todoerti M, et al. Subclinical remodelling of draining lymph node structure in early and established rheumatoid arthritis assessed by power Doppler ultrasonography. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(8):1395–400. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, Zhou Q, Wood RW, Kuzin I, Bottaro A, Ritchlin CT, et al. CD23(+)/CD21(hi) B-cell translocation and ipsilateral lymph node collapse is associated with asymmetric arthritic flare in TNF-Tg mice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(4):R138. doi: 10.1186/ar3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.