Abstract

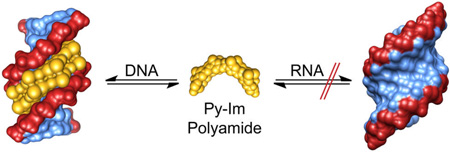

Groove specificity. Pyrrole-imidazole polyamides are well-known for their specific interactions with the minor groove of DNA. Here we demonstrate that polyamides do not similarly bind duplex RNA, and offer a structural rationale for the molecular-level discrimination of nucleic acid duplexes by minor groove binding ligands.

Keywords: DNA recognition, imidazole, polyamide, pyrrole, RNA recognition

Py-Im polyamides bind the minor groove of DNA in a sequence specific manner, encoded by antiparallel side-by-side pairs of pyrrole (Py) and imidazole (Im) carboxamides.[1–3] Im/Py pairs distinguish the edge of a G•C base pair from C•G, Py/Py pairs are degenerate for T•A and A•T, and hydroxypyrrole/pyrrole pairs (Hp/Py) distinguish T•A from A•T base pairs.[4–8] Hairpin Py-Im polyamides have been shown to bind specific DNA sequences with affinities typical of transcription factors.[4,9] Eight-ring oligomers are sufficiently small to permeate cell membranes, traffic to the nucleus,[10,11] access chromatin,[12] and disrupt protein-DNA interactions.[13,14] Hairpin and cyclic Py-Im polyamides targeted to the androgen response element (ARE) have been shown to modulate expression of PSA and other AR driven genes.[13,15,16]

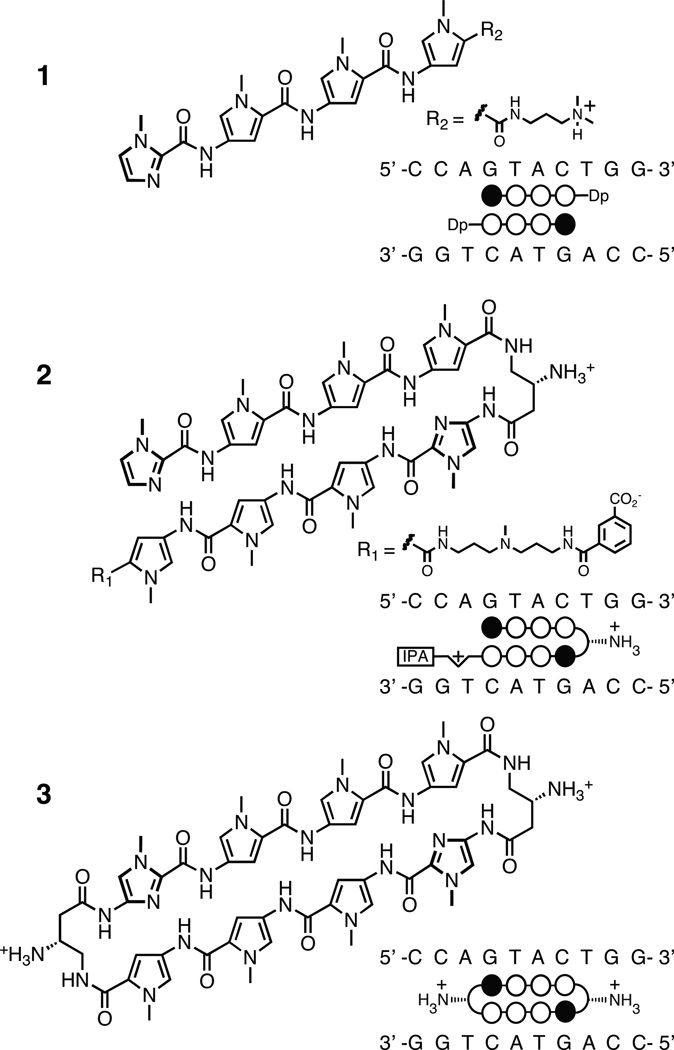

The question arises whether the “pairing rules” are specific for the DNA double helix or whether these programmable oligomers could bind double helical RNA as well. The magnitude of DNA thermal stabilization (ΔTm) of DNA-polyamide complexes has been previously used to measure polyamide binding affinity and probe for mismatched interactions.[17,18] We report here thermal melting temperature analyses to compare the ability of three Py-Im polyamide architectures to bind helical DNA and RNA. The distinct architectures consist of an antiparallel 2:1 binding polyamide ImPyPyPy 1, a hairpin polyamide ImPyPyPy-γ-ImPyPyPy 2, and the corresponding cycle 3 (Fig. 1). Each polyamide examined utilizes the same four ring pairs to target the 6 base pair motif 5'-WGWWCW-3'. Analyses were performed on 10-mer palindromic DNA (5'-CCAGTACTGG-3', Tm = 46.1 °C) and RNA (5'-CCAGUACUGG-3', Tm = 60.4 °C) oligonucleotides. We find polyamides 1–3 provide a large thermal stabilization to dsDNA but not dsRNA. We also provide a molecular rational for the ability of polyamides to selectively distinguish DNA over RNA based on previous structural data.[6,7,12,14,16]

Figure 1.

Structures of polyamides 1–3 and their DNA binding sites. Polyamide shorthand code: closed circles, N-methylimidazole; open circles, N-methylpyrrole; half diamond with cross, 3,3’-diamino-N-methyl-dipropylamine; Dp, 3-(dimethylamino)-propylamine; IPA, isophthalic acid.

As shown in Table 1, polyamides 1–3 afforded an increase in the duplex DNA melting temperature relative to the native DNA duplex. The degree of thermal stabilization is highly dependent on covalent linkage of the two antiparallel polyamide strands. As anticipated from previous DNase I footprinting and kinetic studies,[19,20], hairpin polyamide 2 provides significantly higher thermal stabilization than the unlinked antiparallel dimer of 1, and the cyclic polyamide 3 yielded the strongest stabilization (ΔTm = 36.6 °C). The analogous double strand RNA exhibited no thermal stabilization in the presence of a large excess (up to four equivalents) of any of the three polyamides 1–3 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Thermal melting temperatures for dsDNA and dsRNA duplexes in the presence and absence of polyamides 1–3.

| a] |

dsDNA sequence 5’-CCAGTACTGG-3’ 3’-GGTCATGACC-5’ |

dsRNA sequence 5’-CCAGUACUGG-3’ 3’-GGUCAUGACC-5’ |

||

| Polyamide | Tm / °C | ΔTm / °C | Tm / °C | ΔTm / °C |

| - | 46.1 (±0.8) | - | 60.4 (±0.6) | - |

| 1 | 52.8 (±0.4) | 6.6 (±0.9) | 59.7 (±0.3) | −0.6 (±0.7) |

| 2 | 72.3 (±0.5) | 26.2 (±1.0) | 60.7 (±0.5) | 0.3 (±0.8) |

| 3 | 82.8 (±0.6) | 36.6 (±1.0) | 59.9 (±0.8) | −0.5 (±10) |

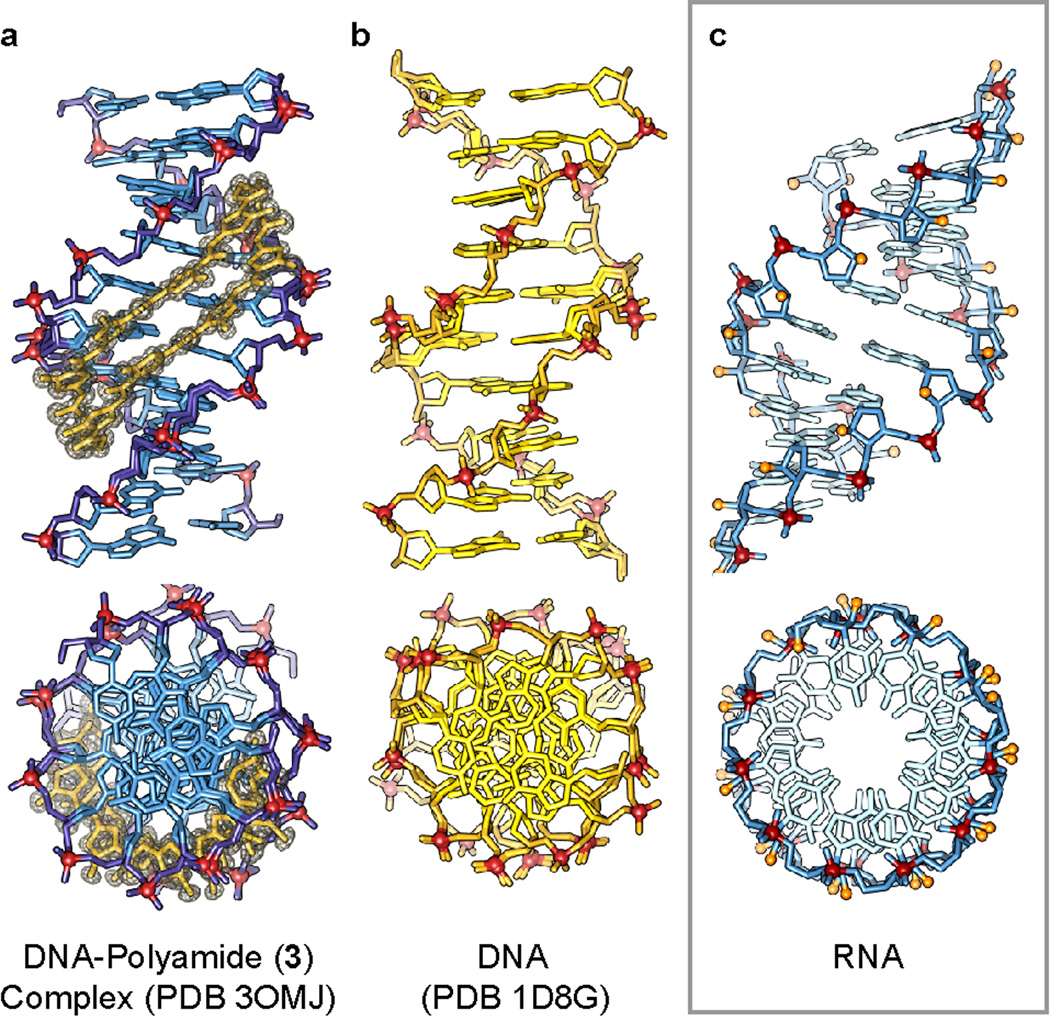

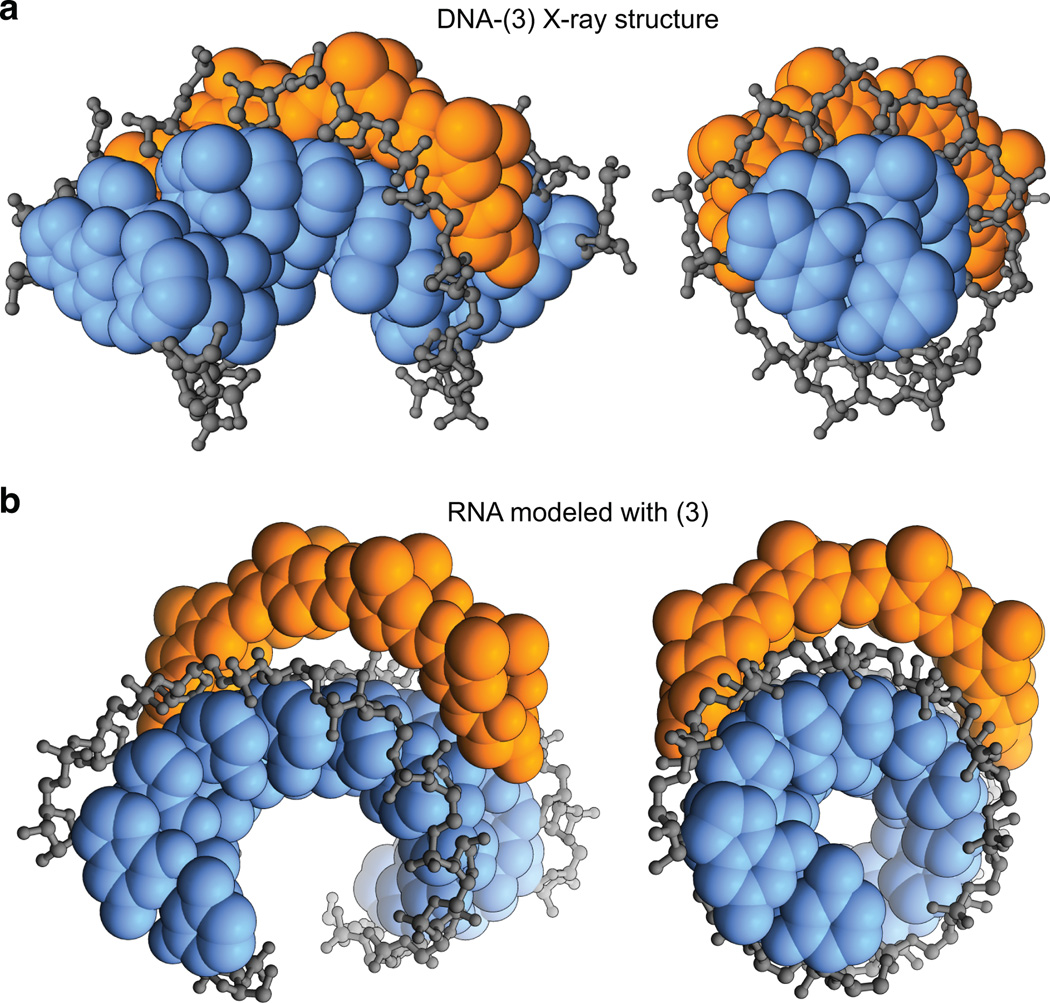

While minor groove binding of Py-Im polyamides to helical DNA has been extensively studied, the ability of modular hairpin polyamides to bind helical RNA has received little attention. In duplex RNA, the thymine-adenine base pair is replaced with a uracil-adenine pairing. However, in both structures the hydrogen bonding functionalities presented by the edges of the four Watson-Crick bases in the minor groove are identical (Figure 2).[21] Studies from our lab and others have shown that the binding of polyamides is unaffected by nucleotide substitutions projecting into the major groove of DNA.[20,22] Therefore, the inability of Py-Im polyamides to bind dsRNA is due to differences in the shape of helical RNA compared to DNA resulting from the 2’-OH on the ribose sugar of RNA. We have illustrated these structural differences by modeling an ideal RNA helix and comparing it to the structure of free or cycle 3-bound DNA (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).[16,21] The extra hydroxyl group of RNA affects both the overall structure and rigidity of dsRNA due to a conformational preference for a C3’-endo ribose sugar pucker (Fig. 3c). The ribose conformation forces the RNA helix into an A or A’-form conformation due to steric incompatibility of the 2’-OH with the B-form DNA conformation, a structure which prefers a C2’-endo sugar. The conformational rigidity enforced by this structure stands in contrast to the flexible sequence dependent microstructure of DNA, which undergoes large changes in minor and major groove geometry upon polyamide binding (Fig. 2).[14,16] The conformational mobility of DNA relative to RNA is reflected in the relative thermal stability of the two molecules (Table 1). Beyond rigidity, the structure of A-form RNA has an 11-fold helix with a narrow, deep major groove and a much wider, shallower minor groove compared to DNA (Fig. 2). This shallow minor groove is incompatible with many of the criteria required for Py-Im polyamide and, in general, small molecule-nucleic acid binding such as the minimization of water exposed hydrophobic surfaces, complementary pairing of buried hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, maximization of vander Waals interactions, solvation or neutralization of all charges, and maximization of attractive and minimization of repulsive interactions. In addition, the base pairs of A-form RNA are inclined and displaced from the helix axis causing an overall expansion of the helix width, leading to a shallow curvature of the minor groove floor. This results in a lack of shape complementarity for RNA with Py-Im polyamides such as 1–3, whose Py and Im subunits are known to be slightly overcurved relative even to DNA (Fig. 3).[23]

Figure 2.

Comparison of the overall structure of dsDNA in the presence and absence of polyamide to the analogous sequence of dsRNA. a) X-ray structure (PDB: 3OMJ) of polyamide 3 complexed to the DNA sequence d(5'-CCAGTACTGG-3') solved at 0.95 Å.[16] Electron density map of the polyamide is contoured at the 1.0 σ level. b) Native DNA structure (PDB: 1D8G) d(5'-CCAGTACTGG-3') solved at ultrahigh resolution (0.74 Å) by Rees and coworkers.[21] c) Model of ideal A-form dsRNA for comparison.

Figure 3.

Structural basis for selective dsDNA versus dsRNA binding. a) Crystal structure of DNA-polyamide 3 complex (PDB: 3OMJ) showing shape complementary and favorable hydrophobic interactions with the sugar-phosphate backbone (gray). Orange, polyamide; blue, aromatic DNA bases. b) Coordinates of cyclic polyamide 3 docked in the minor groove of the putative binding site on a model of ideal A-form dsRNA.

In summary, the inability of Py-Im polyamides 1–3 to bind helical RNA stems from a reduction in polyamide-RNA shape complementarity and reduced solvation of the wide shallow A-form RNA minor groove that diminishes the enthalpic and entropic components of polyamide-minor groove binding.[17] This agrees with previous observations that the minor-groove binding natural products netropsin and distamycin, and the dye Hoechst show low affinity for duplex RNA.[24–26] In contrast, many RNA-targeting agents, including aminoglycosides and intercalators, are less discriminating and show modest binding with both DNA and RNA.[27,28] The ability of Py-Im polyamides to distinguish DNA from RNA highlights their utilility as specific probes of DNA-mediated processes.

The development of sequence specific small molecules for targeting RNA remains a challenge.[29,30] Importantly, the field lacks a pivotal natural product lead such as distamycin which benefited the DNA recognition field with the N-methylpyrrole amino acid module.[31] In contrast to the sequence-based specificity of DNA-binding polyamides, most RNA-binding compounds demonstrate structure-based specificity, targeting combinations of non-paired elements such as hairpins, bulges, and internal loops.[29,32] This orthogonal approach to selectivity provides unique challenges and opportunities for RNA recognition. However, analogies can be drawn between milestones in the development of Py-Im polyamides and recent advances towards programmable molecular recognition of RNA. For example, the 2:1 structure of the natural product distamycin informed the development of sequence-specific Py-Im ring pairs.[33] Similarly, structures of biomedically relevant RNA targets have helped inform RNA ligand design.[34–38] Introduction and optimization of the three methylene aliphatic turn unit connecting two Py-Im domains was necessary to increase polyamide-DNA binding affinity in the shape of a hairpin foldamer.[39] Analagously, several studies have demonstrated the profound effect linker-enforced polyvalency can have on the affinity and specificity of small molecule-RNA interactions.[32,40,41] Finally, just as quantitative footprinting and microarray screening guided Py-Im polyamide design, recent high-throughput methods provide new tools for analysis and redesign of RNA-ligand binding specificity.[42,43] Combining insights from structure, design, and screening will help develop the next-generation of RNA-binding small molecules, an intellectually rich structure-function challenge for chemical biology.[29,30]

Experimental Section

Synthesis and Purification

Polyamides were synthesized as previously described and purified by reverse phase HPLC.[44] Oligonucleotides were purchased HPLC purified from Trilink Biotechnologies (San Diego, CA). Oligonucleotides were used as received for melting temperature studies. Single strand DNA and polyamides were quantitated by UV-Vis spectroscopy on a Hewlett-Packard diode array spectrophotometer (Model 8452 A).

Melting Temperature Analysis

Melting temperature analysis was performed on a Varian Cary 100 spectrophotometer equipped with a thermo-controlled cell holder possessing a cell path length of 1 cm. A degassed aqueous solution of 10 mM MOPS, 10 mM NaCl, at pH 7.0 was used as analysis buffer. DNA duplexes and hairpin polyamides were mixed in 1:1 stoichiometry to a final concentration of 2 µM for each experiment. Prior to analysis, samples were heated to 90 °C and cooled to a starting temperature of 23 °C with a heating rate of 5 °C/min for each ramp. Denaturation profiles were recorded at λ = 260 nm from 23 °C to 90 °C with a heating rate of 0.5 °C/min. The reported melting temperatures were defined as the maximum of the first derivative of the denaturation profile.

Structural Analysis and Modeling

Ideal RNA was generated using the X3DNA program.[45] Docking, structural analysis, and figures were prepared using UCSF Chimera.[46]

Footnotes

Support was provided by NIH GM27681.

References

- 1.Wade WS, Mrksich M, Dervan PB. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:8783. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mrksich M, Wade WS, Dwyer TJ, Geierstanger BH, Wemmer DE, Dervan PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wade WS, Mrksich M, Dervan PB. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11385. doi: 10.1021/bi00093a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trauger JW, Baird EE, Dervan PB. Nature. 1996;382:559. doi: 10.1038/382559a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White S, Szewczyk JW, Turner JM, Baird EE, Dervan PB. Nature. 1998;391:468. doi: 10.1038/35106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kielkopf CL, White S, Szewczyk JW, Turner JM, Baird EE, Dervan PB, Rees DC. Science. 1998;282:111. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kielkopf CL, Baird EE, Dervan PB, Rees DC. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:104. doi: 10.1038/nsb0298-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dervan PB. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:2215. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu CF, Phillips JW, Trauger JW, Farkas ME, Belitsky JM, Heckel A, Olenyuk BZ, Puckett JW, Wang CC, Dervan PB. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:6146. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Best TP, Edelson BS, Nickols NG, Dervan PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2035074100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edelson BS, Best TP, Olenyuk B, Nickols NG, Doss RM, Foister S, Heckel A, Dervan PB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2802. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edayathumangalam RS, Weyermann P, Gottesfeld JM, Dervan PB, Luger K. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401743101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nickols NG, Dervan PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chenoweth DM, Dervan PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906532106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chenoweth DM, Harki DA, Phillips JW, Dose C, Dervan PB. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7182. doi: 10.1021/ja901309z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chenoweth DM, Dervan PB. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14521. doi: 10.1021/ja105068b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilch DS, Poklar N, Gelfand CA, Law SM, Breslauer KJ, Baird EE, Dervan PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muzikar KA, Meier JL, Gubler DA, Raskatov JA, Dervan PB. Org Lett. 2011;13:5612. doi: 10.1021/ol202285y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herman DM, Turner JM, Baird EE, Dervan PB. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:1121. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baliga R, Baird EE, Herman DM, Melander C, Dervan PB, Crothers DM. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3. doi: 10.1021/bi0022339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kielkopf CL, Ding S, Kuhn P, Rees DC. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:787. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minoshima M, Bando T, Sasaki S, Fujimoto J, Sugiyama H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2889. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly JJ, Baird EE, Dervan PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmer C, Reinert KE, Luck G, Wahnert U, Lober G, Thrum H. J Mol Biol. 1971;58:329. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wartell RM, Larson JE, Wells RD. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:6719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho J, Rando RR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2158. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.10.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arya DP, Coffee RL, Jr, Xue L. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:4643. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailly C, Colson P, Houssier C, Hamy F. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1460. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.8.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas JR, Hergenrother PJ. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1171. doi: 10.1021/cr0681546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan L, Disney MD. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:73. doi: 10.1021/cb200447r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arcamone F, Penco S, Orezzi P, Nicolella V, Pirelli A. Nature. 1964;203:1064. doi: 10.1038/2031064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michael K, Wang H, Tor Y. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:1361. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelton JG, Wemmer DE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parsons J, Castaldi MP, Dutta S, Dibrov SM, Wyles DL, Hermann T. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:823. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mooers BH, Logue JS, Berglund JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar A, Park H, Fang P, Parkesh R, Guo M, Nettles KW, Disney MD. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9928. doi: 10.1021/bi2013068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao F, Zhao Q, Blount KF, Han Q, Tor Y, Hermann T. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:5329. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilbert SD, Mediatore SJ, Batey RT. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14214. doi: 10.1021/ja063645t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mrksich M, Parks ME, Dervan PB. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:7983. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee MM, Childs-Disney JL, Pushechnikov A, French JM, Sobczak K, Thornton CA, Disney MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17464. doi: 10.1021/ja906877y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee MM, Pushechnikov A, Disney MD. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:345. doi: 10.1021/cb900025w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warren CL, Kratochvil NC, Hauschild KE, Foister S, Brezinski ML, Dervan PB, Phillips GN, Jr, Ansari AZ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509843102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Disney MD, Labuda LP, Paul DJ, Poplawski SG, Pushechnikov A, Tran T, Velagapudi SP, Wu M, Childs-Disney JL. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11185. doi: 10.1021/ja803234t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belitsky JM, Nguyen DH, Wurtz NR, Dervan PB. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:2767. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu XJ, Olson WK. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]