Abstract

Circadian clock function in Arabidopsis thaliana relies on a complex network of reciprocal regulations among oscillator components. Here, we demonstrate that chromatin remodeling is a prevalent regulatory mechanism at the core of the clock. The peak-to-trough circadian oscillation is paralleled by the sequential accumulation of H3 acetylation (H3K56ac, K9ac), H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), and H3K4me2. Inhibition of acetylation and H3K4me3 abolishes oscillator gene expression, indicating that both marks are essential for gene activation. Mechanistically, blocking H3K4me3 leads to increased clock-repressor binding, suggesting that H3K4me3 functions as a transition mark modulating the progression from activation to repression. The histone methyltransferase SET DOMAIN GROUP 2/ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX RELATED 3 (SDG2/ATXR3) might contribute directly or indirectly to this regulation because oscillator gene expression, H3K4me3 accumulation, and repressor binding are altered in plants misexpressing SDG2/ATXR3. Despite divergences in oscillator components, a chromatin-dependent mechanism of clock gene activation appears to be common to both plant and mammal circadian systems.

Keywords: histone acetylation, histone methylation, circadian rhythms

The functional properties of chromatin are modulated by various mechanisms, including, among others, posttranslational modifications of histones, incorporation of histone variants, and DNA methylation (1, 2). Among histone covalent modifications, acetylation at specific lysine residues of the N-terminal histone tails appears to make DNA more accessible to the transcription machinery, which has been correlated with active transcription (3). Histone methylation, on the other hand, may facilitate the recruitment of chromatin remodeling factors that can either activate or repress transcription, depending on the particular residue that is methylated and the degree of methylation (4). The sequential or combinatorial composition of these histone modifications facilitates the switch between permissive and repressive states of chromatin that ultimately modulate the genome activity in eukaryotes (5).

Epigenetic regulation mediated by histone modifications is also well conserved in plants (6), with a key role in the control of developmental transitions and plant responses to stress (7). Among others, processes such as flowering time, transposon repression, light signaling, and abiotic stress responses are modulated by posttranslational modifications of histones on specific residues (e.g., refs. 8–12). The genomic distribution and combinatorial association of different histone marks in Arabidopsis appear to define various chromatin states that can be correlated with transcriptionally active or inactive genes (13).

More than two-thirds of the Arabidopsis genes contain at least one type of H3K4me (14). The enzymes responsible for methylation are histone lysine methyltransferases (HKMTases), which usually contain a conserved SET domain that harbors the enzymatic activity (15). The SET domain proteins in Arabidopsis belong to evolutionarily conserved classes with different specificities and different outcomes on chromatin structure (15). The SET DOMAIN GROUP 2/ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX RELATED 3 (SDG2/ATXR3) was proposed to play a major role in H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) in Arabidopsis (16, 17). Loss of SDG2/ATXR3 function results in pleiotropic phenotypes, as well as a global decrease of H3K4me3 accumulation and altered expression of a large number of genes.

A precise regulation of gene expression is not only essential for plant responses to environmental stresses and developmental transitions but also for proper function of the circadian clock. The circadian clockwork allows plants to anticipate environmental changes and adapt their activity to the most appropriate time of day (18). In Arabidopsis thaliana, the core of the oscillator is composed of morning- and evening-expressed components that regulate their expression in a highly complex network of interconnections (19). The transcription factors CCA1 (CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1) (20), LHY (LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL) (21), and the PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR (PRR) proteins (PRR9, -7, and -5) (22) have peak phases of expression during the day, whereas TOC1 (TIMING OF CAB EXPRESSION 1 or PRR1) (23, 24), GI (GIGANTEA) (25, 26), and the members of the Evening Complex (EC) (27), all have evening peak-phase oscillations. The transcriptional repressing activity of TOC1 has been recently added to the myriad plant clock repressors (28, 29), opening the question about the components and mechanisms responsible for activation (30).

The large fraction of genes regulated by the circadian clock suggests that transcriptional control occurs by higher-order changes in chromatin structure. Indeed, histone modifications are coupled with the generation of rhythms at the core of the oscillator. Specifically, rhythmic changes in the pattern of H3 acetylation at TOC1 promoter correlate with TOC1 circadian expression (31). Two MYB transcription factors antagonistically contribute to this regulation. At dawn, CCA1 represses TOC1 expression by promoting histone deacetylation, whereas REVEILLE 8/LHY-CCA1-LIKE 5 acts as an activator and facilitates histone acetylation (31, 32). A recent report has extended this analysis showing that CCA1 and LHY are also subjected to rhythmic changes in H3 acetylation and methylation (33). Histone demethylation might also be connected with the Arabidopsis circadian clock because JUMONJI DOMAIN CONTAINING 5/30 (JMD5/JMD30) loss-of-function and JMD5/JMD30-overexpressing plants affect circadian period by the clock (34, 35).

Here, we have investigated the spatiotemporal distribution of daily chromatin transitions and show their functional roles at the core of the oscillator. The main activating histone marks, H3 acetylation and H3K4me3, are enriched around the 5′ end of the oscillator genes and regulate the timing of the oscillator gene expression. Despite their similar activating function, acetylation and trimethylation oscillate with a different phase, which suggests a degree of specificity in their respective clock-related roles. Reduction of H3K4me3 is concomitant with increased clock-repressor binding, suggesting that H3K4me3 might impede an advanced phase of repressor activity, thus facilitating the proper transition from activation to repression. Molecularly, the use of plants misexpressing SDG2/ATXR3 reveals that this histone methyltransferase might contribute to H3K4me3 at the core of the clock. Collectively, our studies indicate that the precise timing and combinatorial accumulation of histone marks are essential for proper transcriptional regulation at the core of the clock.

Results and Discussion

Specific Distribution of Histone Marks Along the Genomic Structure of the Oscillator Genes.

To gain further insights into the connection of chromatin remodeling at the core of the clock, we performed ChIP assays at Zeitgeber Time 3 and 15 (ZT3 and ZT15) in wild-type (WT) plants grown under 12-h light/12-h dark (LD) cycles. Analyses were initiated with antibodies to H3K56 acetylated (H3K56ac) and H3K4 trimethylated (H3K4me3), and different regions were amplified along the genomic structure of the main oscillator genes. We found specific enrichment of H3K56ac and H3K4me3 around the 5′ end of both sets of core genes (Fig. S1), whereas no significant amplification was obtained in samples similarly processed but omitting the antibody in the ChIP assay (Figs. S1 and S2). The results are consistent with a recent publication showing the distribution of H3K4me3 and H3ac on TOC1, CCA1, and LHY loci (33). The decrease in 5′ to 3′ direction along the oscillator genes suggest that both types of modifications might dissociate from the elongating RNA–polymerase II during RNA synthesis.

The morning-expressed oscillator genes (LHY, PRR9, CCA1, and PRR7) exhibited increased H3K56ac and H3K4me3 at ZT3 compared with ZT15. In contrast, the pattern of these histone marks clearly accumulated at ZT15 in the evening-expressed oscillator genes (TOC1 and LUX ARRYTHMO) (Figs. S1 and S2). The timing of these histone marks suggest that the temporal modulation of H3K56ac and H3K4me3 is in tune with the circadian gene expression. These results are in agreement with the previously described connection of H3ac and H3K4me3 with gene activation (13, 33). The phase differences in the rhythms of histone marks among different genes suggest that chromatin remodeling is an intrinsic mechanism at the core of the clock.

Genome-wide analyses have defined H3K27 methylation as a major mechanism for silencing of a large number of plant genes (7). The histone mark H3K9me3 is also known to be associated with 40% of Arabidopsis genes, with no overlap with H3K27me3 (36). We, therefore, examined whether these histone marks could also contribute to circadian expression. We used WT plants synchronized under LD cycles and performed ChIP assays with H3K27me3, H3K27me2, and H3K9me3 antibodies. Our results showed that the ChIP signal was, overall, very low and close to background for each antibody, with no evident or reproducible enrichment at a particular time or genomic region, compared with negative controls processed without antibodies (Fig. S3). The results indicate that H3K27me3, H3K27me2, and H3K9me3 do not significantly contribute to the regulation of circadian gene expression at the core of the clock.

Rhythms in Histone Marks at the Core of the Arabidopsis Oscillator.

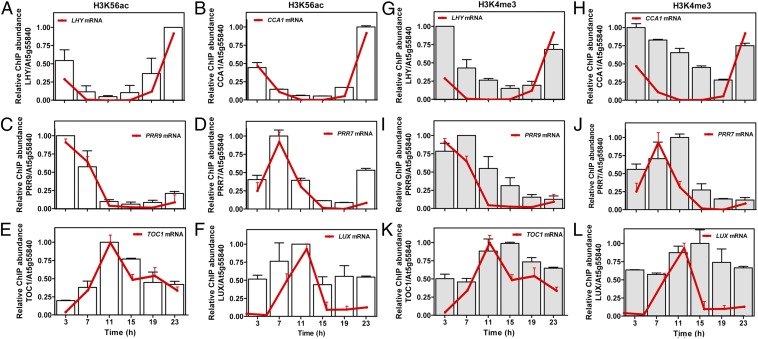

We next performed a time course analysis of H3K56ac and H3K4me3 accumulation over a 24-h diurnal cycle. We found that for the morning and the evening set of core genes, both marks followed a robust oscillation that resembled the rhythmic expression of the respective transcripts (Fig. 1). The phase of H3K56ac matched that of the mRNA accumulation, with the peak of H3K56ac temporally coinciding with the peak of mRNA (Fig. 1 A–F). The rhythmic acetylation of H3K9 was very similar to that observed for H3K56 (Fig. S4), which is consistent with previous findings focused on the TOC1 promoter (31). The phase of H3K4me3, on the other hand, was delayed, with a peak about 4 h later, compared with the peak of H3K56ac accumulation (Fig. 1 G–L and Fig. S5). Slower decay of H3K4me3 was also observed during the declining phase of H3K56ac and mRNA oscillation. These results suggest that the rhythms in H3ac and H3K4me3 might facilitate the transcriptional activation of the morning- and evening-expressed oscillator genes. The oscillations in histone marks might rhythmically change the chromatin structure, conferring differential accessibility to the transcriptional machinery and regulators controlling the expression of the genes at a specific time of the day. The differential pattern of accumulation and the differences in peak phases also open the possibility of specific roles for acetylation and K4me3.

Fig. 1.

Rhythmic oscillation of H3K56Ac and H3K4Me3 and its association with oscillator gene expression. ChIP assays of H3K56Ac (A–F) and H3K4me3 (G–L) were performed in WT plants sampled every 4 h over a 24-h LD cycle. Primers encompassing the peak of H3K56Ac and H3K4me3 for each gene (Fig. S1) were used to amplify LHY (A and G), CCA1 (B and H), PRR9 (C and I), PRR7 (D and J), TOC1 (E and K), and LUX (F and L). Values are represented as means ± SEM. Enrichment was normalized relative to the control At5g55840. Expression profiling for each gene is overlapped in each graph (red line). Gene expression was analyzed in plants grown under LD cycles. mRNA abundance was normalized to IPP2 (isopentenyl pyrophosphate:dimethyl-allyl pyrophosphate isomerase) expression. Values are represented as means ± SEM. Data were normalized relative to the maximum value to facilitate comparisons between the ChIP and the expression assays and among the different genes at the various time points.

Histone demethylation has been connected with the Arabidopsis circadian clock (34, 35). Although its mechanism of action remains unknown, it is plausible that H3K4me3 could serve as a substrate for histone demethylases. If that is the case, the oscillations in H3K4me3 could be followed by rhythms in H3K4me2. Indeed, our time-course analyses of H3K4me2 over the diurnal cycle showed that the peak of H3K4me2 was nearly antiphasic to H3ac, with higher H3K4me2 accumulation at times when H3ac is low and vice versa (Fig. S6). This pattern was particularly evident for the morning-expressed genes. The fact that H3K4me2 accumulates when H3ac and the mRNA are low suggests that H3K4me2 might function as a repressive mark contributing to the low abundance of the morning-expressed genes during the night (Fig. S6). In contrast, H3K4me2 accumulation appears to mark gene repression during the first part of the day for the evening-expressed genes. Comparisons of H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 revealed a certain degree of coexistence of both marks around dusk for the morning set of core genes and around dawn for the evening-expressed genes (Fig. S6). Collectively, our studies reveal a dynamic and complex pattern of histone marks with the sequential enrichment H3ac→H3K4me3→H3K4me2 that temporally correlates with the peak-to-trough rhythmic expression. H3ac and H3K4me3 coexist during gene activation, whereas H3K4me3 and H3K4me2 share high or moderate abundance during the declining phase and trough.

Pharmacological Inhibition of Histone Marks Alters Oscillator Gene Expression.

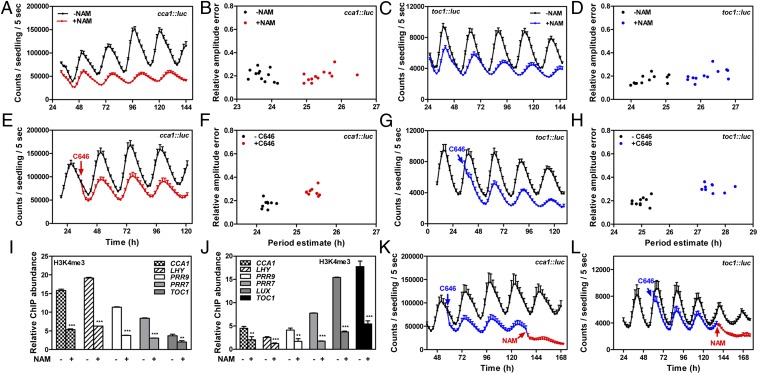

To explore whether the rhythms in histone marks are associated with transcriptional regulation, we examined luminescence from seedlings expressing the CCA1 and TOC1 promoter fused to the luciferase (CCA1::LUC, TOC1::LUC) in the absence or in the presence of specific inhibitors. The rhythms in seedlings treated with nicotinamide (NAM) [shown previously to decrease H3K4me3 (37)] showed a delayed phase and a long-period phenotype that was accompanied by a reduced amplitude of both CCA1::LUC and TOC1::LUC expression (Fig. 2 A–D and Fig. S7). Similar results were obtained irrespective of the time of NAM treatment and when gene expression was examined by RT–quantitative PCR (RT-Q-PCR) (Fig. S7). The inhibitory effect of NAM correlated with a significant decrease in H3K4me3 both at the peak and the trough of gene expression (Fig. 2 I–J). NAM can also inhibit histone deacetylase activity (38). However, our analysis showed that H3K56ac accumulation was reduced in NAM-treated plants (Fig. S8). These results are consistent with the decreased amplitude of oscillator gene expression and with the proposed interconnection of methylation and acetylation. Treatment with NAM of plants expressing the promoter of the output gene CCR2 (COLD-CIRCADIAN RHYTHM-RNA BINDING2) fused to the luciferase (CCR2::LUC) (24) altered the period, as expected, but did not affect the amplitude of the rhythms (Fig. S7), which suggests that the effects of NAM on the amplitude of the oscillator genes are direct and specific. We favor the scenario in which the oscillator activity is, overall, reduced by NAM, which renders a clock to run slower than in nontreated plants. NAM also affects the amplitude of cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyt) oscillation (39). However, our analyses were performed with plants grown on sucrose, which abolishes the oscillation of [Ca2+]cyt (40). The effects of NAM are not likely attributable to alteration of poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP) (41) because treatment with the PARP inhibitor thymidine (41) does not phenocopy the effects of NAM (Fig. S7). Consistent with our ChIP experiments, blocking histone acetylation by inhibition with α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone (MB-3) (42) or with C646 (43) reduced histone acetylation and also affected CCA1::LUC and TOC1::LUC expression (Fig. 2 E–H and Fig. S8). The repressing effects were observed very rapidly following treatment (Fig. 2 E and G), suggesting that the decrease in histone acetylation and trimethylation is directly responsible for the repression. Notably, the combined use of NAM and C646 completely abolished the rhythmic expression (Fig. 2 K and L), which suggests that acetylation and H3K4me3 are essential marks contributing to the raising phase of CCA1 and TOC1.

Fig. 2.

Effects of blocking histone K4 trimethylation and acetylation on clock gene expression. CCA1::LUC (A, E, and K) and TOC1::LUC (C, G, and L) luminescence in WT plants entrained under LD cycles and subsequently released to constant light (LL) conditions. Luminescence was examined in the absence or presence of NAM (A and C), C646 (E and G), or C646 plus NAM (K and L). Period estimates of CCA1::LUC (B and F) and TOC1::LUC (D and H) expression from individual traces examined by fast Fourier transform–nonlinear least-squares (FFT-NLLS) best-fit algorithm analysis. ChIP analysis of H3K4me3 in the presence and in the absence of NAM at ZT3 (I) and ZT15 (J). Enrichment was normalized relative to the control At2g26560 (17). Two-tailed t test analysis with 95% of confidence shows the statistical relevance of the differences: **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0001. Arrows indicate the circadian time of inhibitor administration. Data are the means ± SEM of the luminescence of 5–10 individual seedlings.

Inhibition of H3K4me3 Leads to Increased Clock-Repressor Binding and Gene Repression.

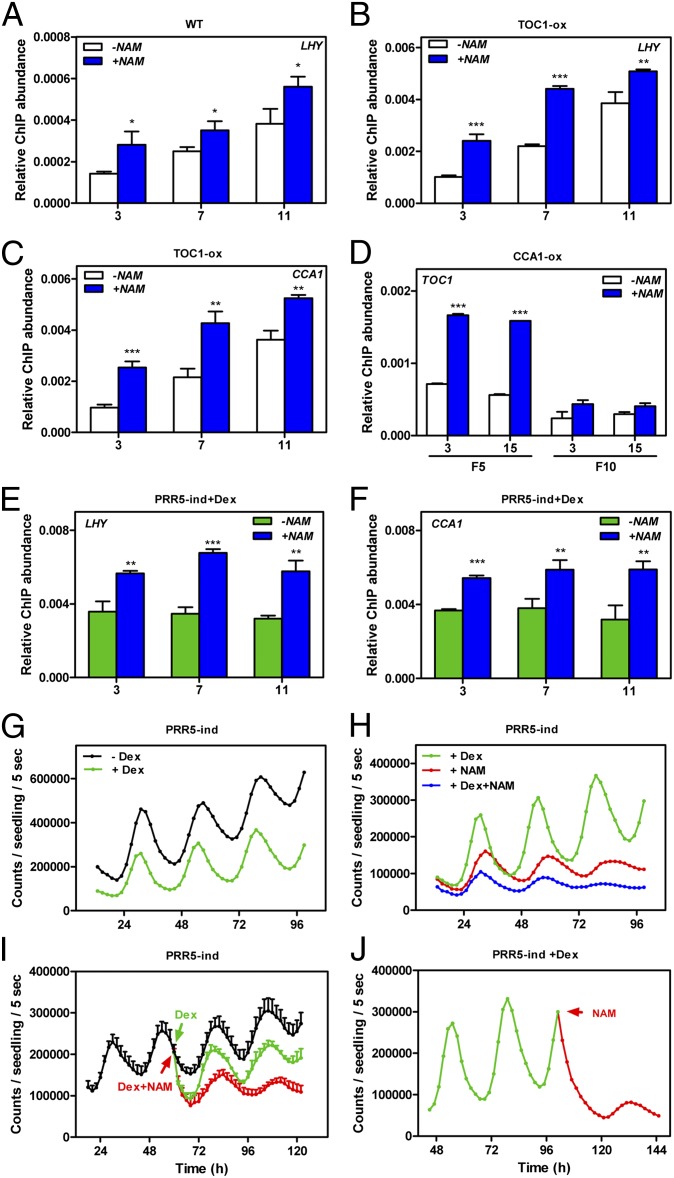

Both H3ac and H3K4me3 function as activating marks. However, H3K4me3 extends temporally beyond the peak of H3ac, overlapping with both H3ac and H3K4me2. Extended accumulation of H3K4me3 might be helpful to modulate the progression from gene activation to repression. If that is the case, then the recruitment of clock repressors to the promoters of the oscillator genes might be influenced by the status of H3K4me3. To check this possibility, we examined by ChIP assays the effects of NAM treatments on TOC1 binding to its target genes LHY and CCA1. Our studies revealed a significant increase (P < 0.05) of TOC1 binding to the CCA1 and LHY promoters in plants treated with NAM compared with mock-treated plants (Fig. 3A and Fig. S9), whereas no significant enrichment was observed when toc1-2 mutant plants were used for the ChIP assays (Fig. S9). These results are noteworthy because NAM treatment reduces the expression of TOC1. To avoid possible interferences attributable to the changes in TOC1 expression by NAM, we also checked TOC1 binding in plants overexpressing TOC1 under the 35S promoter. Similar to our results in WT plants, we observed a significant increment (P < 0.01) of TOC1 binding in plants treated with NAM (Fig. 3 B and C). The effects are not restricted to the evening-expressed repressors, because binding of CCA1 to its target, TOC1, was also significantly increased (P < 0.001) in CCA1-overexpressing plants treated with NAM (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Effects of blocking histone K4 trimethylation on clock-repressor binding and oscillator gene expression. ChIP assays of TOC1 binding to LHY in WT plants (A) and binding to LHY (B) and CCA1 (C) in TOC1-ox plants. Plants were grown under LD cycles, and samples were analyzed at ZT3, ZT7 and ZT11. (D) ChIP assays of CCA1 binding to TOC1 at ZT3 and ZT15 using primers F5 and F10 (Fig. 1). Binding was examined in the absence (-NAM) or in the presence of NAM (+NAM). ChIP assays of PRR5-ind plants grown under LD cycles. Samples were analyzed at ZT3, ZT7, and ZT11. Binding of PRR5 to CCA1 (E) and LHY (F) was examined in plants treated with Dex in the absence (-NAM) or in the presence of NAM (+NAM). Two-tailed t test analysis with 99% of confidence shows the statistical relevance of the differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0001. CCA1::LUC luminescence in PRR5-ind plants entrained under LD cycles and subsequently released to constant light (LL) conditions. Luminescence was examined in the absence or in the presence of Dex (G). Luminescence in plants treated with Dex without or with NAM (H, L, and J). Arrows indicate the circadian time of NAM or Dex administration.

To further corroborate our hypotheses, we also compared binding of the transcriptional repressor PRR5 in the presence or in the absence of NAM. Previous studies have shown that PRR5 represses CCA1 and LHY expression by direct binding to their promoters (44). We used plants expressing the fusion of PRR5 to the hormone-binding domain of mouse glucocorticoid receptor (GR) under the control of the Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV) 35S promoter [PRR5-inducible (PRR5-ind)] (44). The advantages of using the inducible system are twofold. On one hand, expression is controlled by the CaMV 35S promoter, which avoids the possible effects of NAM on the PRR5 promoter. On the other hand, the fact that the GR fusion protein only becomes biologically functional in the presence of dexamethasone (Dex) (45) avoids the possible clock phenotypes that are inherent in constant overexpression. Our ChIP assays with the inducible plants revealed a significant increase (P < 0.01) of PRR5 binding to the CCA1 and LHY promoters in plants treated with Dex and NAM compared with plants treated only with Dex (Fig. 3 E and F). The reduction of H3K4me3 accumulation by NAM and the increased repressor binding suggest that the activating function of H3K4me3 might indeed rely on modulating the timing of clock-repressor binding.

As chromatin residency does not always correlate with transcriptional regulation, we next examined CCA1::LUC luminescence in PRR5-ind plants in the presence and in the absence of NAM. We reasoned that if H3K4me3 modulates the transition from activation to repression then the increased binding of PRR5 by treatment with NAM should be also associated with increased gene repression. Our studies showed that induction of PRR5 led to a significant decrease on CCA1::LUC expression (Fig. 3G), consistent with the previously described repressing function of PRR5 (44). Administration of NAM to Dex-treated plants drastically reduced CCA1::LUC luminescence, with lower signals than those observed for plants treated only with NAM (Fig. 3H). The repressing effects were observed very rapidly following treatment of Dex and/or NAM (Fig. 3 I and J), suggesting that the reduced accumulation of H3K4me3 and the function of PRR5 as an effector molecule are directly responsible for the repression. Our results, thus, show that reduction of H3K4me3 leads to increased PRR5 binding and enhanced repression of CCA1, which suggests that H3K4me3 might modulate directly or indirectly the transition from activation to repression.

Together, our studies suggest that the changes in H3K4me3 directly or indirectly affect the pattern of clock-repressor binding to its target genes. This notion is supported by our findings showing that blocking H3K4me3 increases clock-repressor binding and enhances gene repression. Notably, a delay in the rhythmic oscillation of H3K4me3 relative to H3K9ac was reported at the promoter of the clock component mouse albumin D element–binding protein (DBP) (46). It would be interesting to check whether in the animal circadian systems, H3K4me3 also functions as a transition mark facilitating the proper timing from activation to repression. Clock repressors in mammals (47) and in plants (31) seem to antagonize histone acetyltransferase activities at the core of the clock. It is possible that the observed delayed accumulation of H3K4me3 might “protect” histone acetylation, buffering against the antagonistic function of clock repressors. This notion is consistent with our results showing that H3ac accumulation was reduced in NAM-treated plants.

SDG2/ATXR3 Might Function as a Histone Methyltransferase Responsible for H3K4me3 at the Core of the Clock.

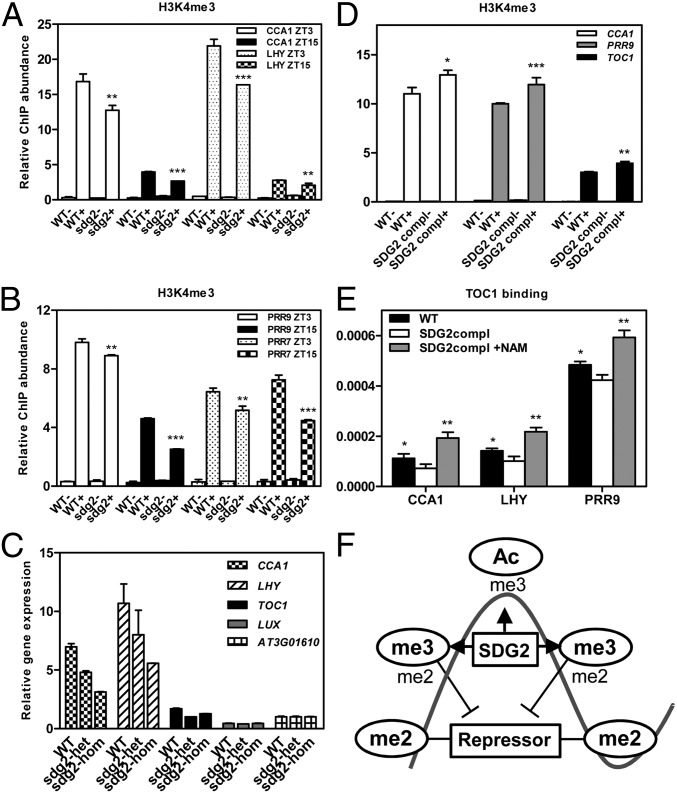

Among more than 30 proteins containing the SDG domain (48), the histone lysine methyltransferase SDG2/ATXR3 was proposed to play an important role in H3K4me3 in Arabidopsis (17). We, therefore, examined the possible function of SDG2/ATXR3 in the regulation of histone methylation at the core of the Arabidopsis clock. Loss of SDG2/ATXR3 function results in very severe developmental phenotypes (17) that complicate the proper interpretation of the ChIP results. We, therefore, analyzed H3K4me3 accumulation in heterozygous sdg2/atxr3 mutants (17). We reasoned that if SDG2/ATXR3 has an important function regulating the clock, then a minor reduction of SDG2/ATXR3 activity might lead to detectable changes in the pattern of H3K4me3. Indeed, our results showed a small but significant reduction (P < 0.01) of H3K4me3 in the heterozygous mutant plants compared with WT (Fig. 4 A and B and Fig. S9). The changes in H3K4me3 were also accompanied by a reduced expression of the oscillator genes (Fig. 4C and Fig. S9). Notably, we observed the opposite phenotypes (i.e., increased H3K4me3; Fig. 4D) when we used SDG2/ATXR3 complementation lines expressing the genomic fragment containing the SDG2/ATXR3 locus in the sdg2/atxr3 mutant background (17).

Fig. 4.

SDG2/ATXR3 might function as a histone methyltransferase at the core of the clock. ChIP analysis of H3K4me3 accumulation in WT plants and in heterozygous sdg2 mutants. Plants were grown under LD cycles, and samples were analyzed at ZT3 and ZT15. H3K4me3 enrichment at the CCA1 and LHY (A) and PRR9 and PRR7 (B) promoters was normalized relative to the control At2g26560 (17). WT(-) and sdg2(-) denote samples processed omitting the antibody in the ChIP assay. (C) RT-Q-PCR analysis of oscillator gene expression in WT plants and in heterozygous (het) and homozygous (hom) sdg2 mutants. Plants were grown under LD cycles, and samples were analyzed at ZT3. Values were normalized relative to the control At3g01610 (17). (D) ChIP analysis of H3K4me3 accumulation in WT plants and in SDG2/ATXR3 complementation lines (compl) expressing the genomic fragment containing the SDG2/ATXR3 locus (17). Plants were grown under LD cycles, and samples were analyzed at ZT3. H3K4me3 enrichment at the CCA1, PRR9, and TOC1 loci was normalized relative to the control At2g26560 (17). WT(-) and SDG2compl(-) denote samples processed omitting the antibody in the ChIP assay. (E) Analysis of TOC1 binding to its target genes in WT and in SDG2/ATXR3 complementation lines. Plants were grown under LD cycles, and samples were analyzed at ZT3. TOC1 binding was also examined in SDG2/ATXR3 complementation lines treated with NAM (+NAM). Two-tailed t test analysis with 99% of confidence shows the statistical relevance of the differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (F) Scheme depicting the combinatorial sequence of chromatin marks accompanying the waveform of the oscillator genes. The marks prevalent at every phase are encircled by the oval line. Overlapping marks are also denoted. The SDG2 function facilitating the accumulation of H3K4me3 is denoted by the arrows. Modulation of the timing of repressor binding by H3K4me3 is depicted by the lines ending in perpendicular dashes.

Based on our results showing that the pattern of H3K4me3 modulates the binding and activity of effector molecules, we next examined whether the changes of H3K4me3 in the sdg2/atxr3 complementation lines could affect the binding of TOC1 to its target genes. Our ChIP assays showed a slight but significant decrease of TOC1 binding in the complementation lines compared with that observed in WT plants (Fig. 4E). The reduced binding was reverted when the complementation lines were treated with NAM (Fig. 4E), suggesting that, indeed, the changes in H3K4me3 are directly responsible for the phenotypes. Our results, thus, indicate that minor changes in SDG2/ATXR3 expression (in the heterozygous mutant and in the complementation lines) significantly affect H3K4me3 accumulation and repressor binding, which suggests that the oscillator genes are very sensitive to slight changes in H3K4me3.

The current model of the Arabidopsis oscillator comprises a myriad of repressors at the core of the clock, but little is known about the mechanisms responsible for activation. Our data define histone acetylation and trimethylation as key elements contributing to oscillator gene activation (Fig. 4F). This conclusion is consistent with findings in the mammalian clockwork, showing that CLOCK, the main positive component of the mammalian oscillator, has histone acetyltransferase activity that is essential for the rhythmic acetylation of histones and nonhistone circadian proteins and for proper functioning of the clock (49). A recent study has further extended this concept, providing a genome-wide view of chromatin remodeling and RNA-polymerase II recruitment at the core of the mammalian clock (50). Our findings and those showing that the activation of mammalian clock genes is coupled with changes in H3ac and H3K4me3 indicate that despite divergences in oscillator components, a chromatin-dependent mechanism of clock gene activation is common to both plant and mammal circadian systems.

Materials and Methods

In Vivo Luminescence Assays and ChIP.

Luminescence was monitored as previously described (51) using a microplate luminometer LB-960 (Berthold Technologies). The ChIP experiments were performed as previously described (52). The list of primers used is shown in Table S1. Details of the analysis and the ChIP experiments are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Gene Expression Analysis.

RNA was isolated (53) using the Purelink Total RNA purification system (Invitrogen) as previously described. The list of primers used is shown in Table S1. Details are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T. Stratmann for comments on the manuscript; Dr. Xiaoyu Zhang for the SDG2/ATXR3 mutant and complementation lines and for sharing data on SDG2/ATXR3; Dr. N. Nakamichi for the PRR5 seeds; and A. Troncoso for initial help with the ChIP assays and with the primer design. This work was supported by the Ramón Areces Foundation (P.M.), Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation Grant BIO2010-16483 (to P.M.), the European Molecular Biology Organization Young Investigator Program (P.M.), and a European Young Investigator Award through the European Science Foundation (to P.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1217022110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of rogram, the chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21(3):381–395. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klose RJ, Bird AP. Genomic DNA methylation: The mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31(2):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293(5532):1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng SS, Yue WW, Oppermann U, Klose RJ. Dynamic protein methylation in chromatin biology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(3):407–422. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8303-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suganuma T, Workman JL. Signals and combinatorial functions of histone modifications. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80(1):473–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-175347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfluger J, Wagner D. Histone modifications and dynamic regulation of genome accessibility in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10(6):645–652. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berr A, Shafiq S, Shen WH. Histone modifications in transcriptional activation during plant development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809(10):567–576. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Y, Michaels SD, Amasino RM. Regulation of flowering time by histone acetylation in Arabidopsis. Science. 2003;302(5651):1751–1754. doi: 10.1126/science.1091109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J-M, et al. Alterations of lysine modifications on the histone H3 N-tail under drought stress conditions in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49(10):1580–1588. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.To TK, et al. Arabidopsis HDA6 regulates locus-directed heterochromatin silencing in cooperation with MET1. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(4):e1002055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charron J-BF, He H, Elling AA, Deng XW. Dynamic landscapes of four histone modifications during deetiolation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21(12):3732–3748. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.066845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caro E, Castellano MM, Gutierrez C. A chromatin link that couples cell division to root epidermis patterning in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2007;447(7141):213–217. doi: 10.1038/nature05763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roudier F, et al. Integrative epigenomic mapping defines four main chromatin states in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2011;30(10):1928–1938. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Bernatavichute YV, Cokus S, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE. Genome-wide analysis of mono-, di- and trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 2009;10(6):R62. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-6-r62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorstensen T, Grini PE, Aalen RB. SET domain proteins in plant development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809(8):407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berr A, et al. Arabidopsis SET DOMAIN GROUP2 is required for H3K4 trimethylation and is crucial for both sporophyte and gametophyte development. Plant Cell. 2010;22(10):3232–3248. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.079962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo L, Yu Y, Law JA, Zhang X. SET DOMAIN GROUP2 is the major histone H3 lysine 4 trimethyltransferase in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(43):18557–18562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010478107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClung CR. The genetics of plant clocks. Adv Genet. 2011;74:105–139. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387690-4.00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doherty CJ, Kay SA. Circadian control of global gene expression patterns. Annu Rev Genet. 2010;44:419–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang ZY, Tobin EM. Constitutive expression of the CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1) gene disrupts circadian rhythms and suppresses its own expression. Cell. 1998;93(7):1207–1217. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81464-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaffer R, et al. The late elongated hypocotyl mutation of Arabidopsis disrupts circadian rhythms and the photoperiodic control of flowering. Cell. 1998;93(7):1219–1229. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81465-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsushika A, Makino S, Kojima M, Mizuno T. Circadian waves of expression of the APRR1/TOC1 family of pseudo-response regulators in Arabidopsis thaliana: Insight into the plant circadian clock. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41(9):1002–1012. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcd043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makino S, Matsushika A, Kojima M, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. The APRR1/TOC1 quintet implicated in circadian rhythms of Arabidopsis thaliana: I. Characterization with APRR1-overexpressing plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43(1):58–69. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strayer CA, et al. Cloning of the Arabidopsis clock gene TOC1, an autoregulatory response regulator homolog. Science. 2000;289(5480):768–771. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fowler S, et al. GIGANTEA: A circadian clock-controlled gene that regulates photoperiodic flowering in Arabidopsis and encodes a protein with several possible membrane-spanning domains. EMBO J. 1999;18(17):4679–4688. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park DH, et al. Control of circadian rhythms and photoperiodic flowering by the Arabidopsis GIGANTEA gene. Science. 1999;285(5433):1579–1582. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nusinow DA, et al. The ELF4-ELF3-LUX complex links the circadian clock to diurnal control of hypocotyl growth. Nature. 2011;475(7356):398–402. doi: 10.1038/nature10182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gendron JM, et al. Arabidopsis circadian clock protein, TOC1, is a DNA-binding transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(8):3167–3172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200355109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang W, et al. Mapping the core of the Arabidopsis circadian clock defines the network structure of the oscillator. Science. 2012;336(6077):75–79. doi: 10.1126/science.1219075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pokhilko A, et al. The clock gene circuit in Arabidopsis includes a repressilator with additional feedback loops. Mol Syst Biol. 2012;8:574. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perales M, Más P. A functional link between rhythmic changes in chromatin structure and the Arabidopsis biological clock. Plant Cell. 2007;19(7):2111–2123. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farinas B, Mas P. Functional implication of the MYB transcription factor RVE8/LCL5 in the circadian control of histone acetylation. Plant J. 2011;66(2):318–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song H-R, Noh Y-S. Rhythmic oscillation of histone acetylation and methylation at the Arabidopsis central clock loci. Mol Cells. 2012;34(3):279–287. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-0103-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones MA, et al. Jumonji domain protein JMJD5 functions in both the plant and human circadian systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(50):21623–21628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014204108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu SX, et al. The Jumonji C domain-containing protein JMJ30 regulates period length in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Physiol. 2011;155(2):906–915. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.167015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turck F, et al. Arabidopsis TFL2/LHP1 specifically associates with genes marked by trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(6):e86. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xydous M, Sekeri-Pataryas KE, Prombona A, Sourlingas TG. Nicotinamide treatment reduces the levels of histone H3K4 trimethylation in the promoter of the mper1 circadian clock gene and blocks the ability of dexamethasone to induce the acute response. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819(8):877–884. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawson M, et al. Inhibitors to understand molecular mechanisms of NAD+-dependent deacetylases (sirtuins) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799(10–12):726–739. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodd AN, et al. The Arabidopsis circadian clock incorporates a cADPR-based feedback loop. Science. 2007;318(5857):1789–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.1146757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson CH, et al. Circadian oscillations of cytosolic and chloroplastic free calcium in plants. Science. 1995;269(5232):1863–1865. doi: 10.1126/science.7569925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rankin PW, Jacobson EL, Benjamin RC, Moss J, Jacobson MK. Quantitative studies of inhibitors of ADP-ribosylation in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(8):4312–4317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biel M, Kretsovali A, Karatzali E, Papamatheakis J, Giannis A. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of a small-molecule inhibitor of the histone acetyltransferase Gcn5. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43(30):3974–3976. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bowers EM, et al. Virtual ligand screening of the p300/CBP histone acetyltransferase: Identification of a selective small molecule inhibitor. Chem Biol. 2010;17(5):471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakamichi N, et al. PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATORS 9, 7, and 5 are transcriptional repressors in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2010;22(3):594–605. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lloyd AM, Schena M, Walbot V, Davis RW. Epidermal cell fate determination in Arabidopsis: Patterns defined by a steroid-inducible regulator. Science. 1994;266(5184):436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.7939683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ripperger JA, Schibler U. Rhythmic CLOCK-BMAL1 binding to multiple E-box motifs drives circadian Dbp transcription and chromatin transitions. Nat Genet. 2006;38(3):369–374. doi: 10.1038/ng1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Etchegaray J-P, Lee C, Wade PA, Reppert SM. Rhythmic histone acetylation underlies transcription in the mammalian circadian clock. Nature. 2003;421(6919):177–182. doi: 10.1038/nature01314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu C, Lu F, Cui X, Cao X. Histone methylation in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:395–420. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.091939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Doi M, Hirayama J, Sassone-Corsi P. Circadian regulator CLOCK is a histone acetyltransferase. Cell. 2006;125(3):497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koike N, et al. Transcriptional architecture and chromatin landscape of the core circadian clock in mammals. Science. 2012;338(6105):349–354. doi: 10.1126/science.1226339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Portolés S, Más P. The functional interplay between protein kinase CK2 and CCA1 transcriptional activity is essential for clock temperature compensation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(11):e1001201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Legnaioli T, Cuevas J, Mas P. TOC1 functions as a molecular switch connecting the circadian clock with plant responses to drought. EMBO J. 2009;28(23):3745–3757. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Más P, Kim WY, Somers DE, Kay SA. Targeted degradation of TOC1 by ZTL modulates circadian function in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2003;426(6966):567–570. doi: 10.1038/nature02163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.