Abstract

Background

Invasion and metastasis is a complex process governed by the interaction of genetically altered tumor cells and the immunological and inflammatory host reponse. Specific T-cells directed against tumor cells and the nonspecific inflammatory reaction due to tissue damage, cooperate against invasive tumor cells in order to prevent recurrences. Data concerning involvement of individual cell types are readily available but little is known about the coordinate interactions between both forms of immune response.

Patients and methods

The presence of inflammatory infiltrate and eosinophils was determined in 1530 patients with rectal adenocarcinoma from a multicenter trial. We selected 160 patients to analyze this inflammatory infiltrate in more detail using immunohistochemistry. The association with the development of local and distant relapses was determined using univariate and multivariate log rank testing.

Results

Patients with an extensive inflammatory infiltrate around the tumor had lower recurrence rates (3.4% versus 6.9%, p = 0.03), showing the importance of host response against tumor cells. In particular, peritumoral mast cells prevent local and distant recurrence (44% versus 15%, p = 0.007 and 86% versus 21%, p < 0.0001, respectively), with improved survival as a consequence. The presence of intratumoral T-cells had independent prognostic value for the occurrence of distant metastases (32% versus 76%, p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

We showed that next to properties of tumor cells, the amount and type of inflammation is also relevant in the control of rectal cancer. Knowledge of the factors involved may lead to new approaches in the management of rectal cancer.

Background

The infiltration of inflammatory cells in cancer tissues is considered an important aspect of the host response in cancer. The altered phenotype of cancer cells might evoke a specific immune response and influx of lymphocytes in the tumor area, while the disorganization and damage of the surrounding tissue leads to a more general inflammatory response, which is mainly present around the tumor. The inflammatory response can have dual effects in the progression of cancer. On one hand inflammatory cells are a prognostic good sign, probably by maintaining control due to elimination of tumor cells [1,2], while on the other hand production of cytokines and growth factors can provide a growth stimulating microenvironment for tumor cells [3-6].

Although in most solid cancer types the emphasis is placed on the presence of T lymphocytes as a specific anti-cancer reaction [7-9], there is a role for the nonspecific inflammation reaction as well, since the presence of NK cells [10,11], macrophages [12-14], mast cells [15-17] and neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes [16-19] have prognostic value in various solid cancer types. The importance of the presence of these different cells is usually analyzed for one cell type. However, the complex interactions between the specific and the general immunologic reaction require an integrated study of the different cell types.

In rectal cancer, the importance of the inflammatory infiltrate is recognized and used in the staging of tumors by the Jass' classification [20]. This classification was initially developed for the prediction of survival, but is also useful in predicting recurrence of disease [21]. One of the most important problems in rectal cancer is local recurrence [22]. Local recurrence causes profound morbidity and is a major cause of rectal cancer related death. In the Netherlands a randomized multicenter trial was started to evaluate the effects of preoperative radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision (TME) on the local recurrence rate in rectal cancer [23]. In this trial radiotherapy, surgery and pathology are standardized, to provide optimal conditions for studying local recurrence.

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the prognostic potential of various inflammatory cell types present in and around rectal carcinoma and to determine their significance for the prognosis in relation to TNM stage. With these data we developed a model integrating the specific and the nonspecific immune response against rectal cancer.

Material and methods

Patient selection

Patients were obtained from the TME trial, a large multicenter trial in the Netherlands, in which 1530 patients were included from January 1996 till December 1999 [23]. In this randomized trial the additional value of preoperative radiotherapy (5 × 5 Gy) is studied when TME (Total Mesorectal Excision) surgery is applied. Radiotherapeutical, surgical and pathological procedures are standardized and quality controlled [24].

For the analysis of the prognostic value of the amount of inflammatory infiltrate as well as eosinophilic granulocytes, we analyzed the data from all eligible patients in this trial (n = 1416). We selected 160 patients for the analysis of the cellular composition of the inflammatory infiltrate in relation to prognosis. Since local recurrence rates are very low when TME surgery is applied, an artifical selection was made to be able to study the role of inflammatory cells in both local and distant control. 40 stage II patients and 40 stage III patients without distant metastases or local recurrence (after a median follow-up of 21 months), 40 with distant metastases without local recurrence and 40 patients with local recurrence without metastases were selected. This selection of patients implies that survival percentages in this study cannot be extrapolated towards the general patient population, however, we can compare the effects of the different cell types on patients' prognosis. Patients were selected from both randomization groups. Analyses were performed using stratification for the randomization arms to exclude a possible therapy related effect.

Follow up of all patients in the trial for the endpoints was conducted according to the trial protocol for at least 36 months. Median follow up at the moment of writing was 19.6 months. Median follow up of the selection of 160 patients is 35.4 months. Distant and local recurrences were checked by a radiation oncologist (CAMM) by radiological and/or histological confirmation.

Tissue preparation

Tissue samples of the primary tumors were fixed in 4% (v/v) phosphate buffered formalin, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections of 4 μm were cut, mounted onto glass slides pretreated with 2% 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (Sigma) and dried overnight. Serial sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or processed for immunohistochemistry.

Evaluation of peritumoral inflammatory infiltrate and eosinophilic granulocytes

Routine hematoxylin and eosin-stained histopathological sections were used to determine the infiltration of lymphocytes and eosinophils at the advancing border of the tumors for all patients by pathologists of the Pathology Review Committee (PRC). Tumor slides of all patients in the trial were send to the PRC, who examined them using the following categories for inflammatory infiltrate: none/few and extensive, as described by Jass et al. [20]. Eosinophilic granulocytes were scored as none/few, moderate and extensive.

Immunohistochemistry

Determination of the various inflammatory cells was assessed by immunohistochemical investigation with the following antibodies: anti-CD3 (Anti Human T Cell, 1: 1600, Dako A/S Glostrup, Denmark), anti-CD4 (1: 400, Novo Castra, Newcastle, UK), anti-CD8 (1: 3200, Novo Castra, Newcastle, UK), anti-CD56 (Anti-N-CAM-16, 1: 3000, Becton Dickinson, San Jose CA, USA), anti-CD68 (Anti Human Macrophage, 1: 6400,Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark), AA-1 (Anti Human Mast Cell Tryptase, 1: 3200, Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark), elastase (Anti-Human Neutrophil Elastase, 1: 800, Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark), EG-2 (Anti-Human ECP/EPX, 1: 1000, Pharmacia Upjohn, Uppsala, Sweden). In brief, sections were deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 20 minutes. Antigen retrieval was performed using 0.01 M citrate buffer (anti-CD3, Ki-67), 1 mM EDTA (anti-CD8, anti-CD56, anti-CD4), and 0.1% Trypsine (anti-CD68), respectively. Subsequently, sections were preincubated with 1% bovine serum albumin. After overnight incubation with the primary antibody, the secondary biotin-conjugated antibody and a tertiary complex of streptavidin-avidin-biotin conjugated to 3-amino-9-ethyl-carbazole were applied. Finally, the sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. Incubation with phosphate-buffered saline instead of the primary antibody served as a negative control.

Scoring methods and categories

The 'running mean' method was used to determine the minimum number of high power fields (HPFs) to be scored for the result to be reliable. Two independent investigators (IDN and AAMS) performed this determination on three different tumors. This was done by calculating stepwise the mean number of inflammatory cells for the total of HPFs until the difference between the successive means became negligibly small. The number of HPFs varied between 11 and 15 for the various cell types; therefor, it was decided to count 15 HPFs (2.1 mm2) for every cell type.

The scoring was performed within the tumor (intratumoral infiltrating cells, present in the stroma of the tumor), as well as separately along the invasive border of the tumor in the surrounding tissue (peritumoral infiltrating cells), by one investigator. Necrotic areas were avoided.

After analysis of the distribution of the numbers of inflammatory infiltrating cells, the counts were divided into two or three categories: none/few, (moderate) and many, based on the distribution of the numbers of cells in the study population (see table 1). Because of the high numbers of peritumoral macrophages, the peritumoral macrophage infiltrate (CD68) was scored semiquantitatively by three independent investigators (IDN, AAMS, and JHJMvK), using three categories: none/few, moderate and extensive. In general, the agreement of the three investigators was good (82.5% agreement). In a few cases with poor agreement, the cases were reviewed using a multi-headed microscope and a score agreed after discussion.

Table 1.

Categorical arrangements for the different cell types in 160 rectal cancer patients.

| cell type (antibody) | intratumoral | peritumoral | |||||

| cells / mm2 | % of patients | cells / mm2 | % of patients | ||||

| eosinophils | (EG-2) | n = 159 | n = 140 | ||||

| none/few | 0-10 | 29 | 0-50 | 31 | |||

| moderate | 11-50 | 50 | 51 - 200 | 43 | |||

| many | > 50 | 21 | > 200 | 26 | |||

| neutrophils | (elastase) | n = 160 | n = 152 | ||||

| none/few | 0-5 | 21 | 0 - 75 | 24 | |||

| moderate | 6 - 50 | 54 | |||||

| many | > 50 | 25 | > 75 | 76 | |||

| mast cells | (tryptase) | n= 160 | n = 151 | ||||

| none/few | 0 -5 | 19 | 0-30 | 25 | |||

| moderate | 6 -50 | 52 | 31 -100 | 59 | |||

| many | > 50 | 29 | > 100 | 16 | |||

| macrophages | (CD68) | n = 159 | |||||

| none/few | 0-50 | 28 | |||||

| moderate | 51 -150 | 50 | |||||

| many | > 150 | 22 | |||||

| NK cells | (CD56) | n = 159 | n = 136 | ||||

| none | 0 | 33 | 0 | 43 | |||

| moderate/many | > 0 | 67 | > 0 | 57 | |||

| T cells | (CD3) | n = 158 | n = 157 | ||||

| none/few | 0-55 | 27 | 0-300 | 20 | |||

| moderate | 56-105 | 36 | 301 - 500 | 51 | |||

| many | >105 | 37 | > 500 | 29 | |||

| CD4+ cells | n = 156 | n = 130 | |||||

| none/few | 0-30 | 43 | 0-20 | 24 | |||

| moderate | 31 -65 | 26 | 21 -110 | 50 | |||

| many | >65 | 31 | > 110 | 26 | |||

| CD8+ cells | n = 159 | n = 122 | |||||

| none/few | 0-15 | 26 | 0-135 | 77 | |||

| moderate | 16-75 | 47 | |||||

| many | >75 | 27 | > 135 | 23 | |||

Peritumoral infiltrate could not be reliably determined in all patients, because of the absence of invasive front in several tumor samples.

Effects of radiotherapy

Since we observed differences in cell counts between both randomization groups [Nagtegaal ID, Marijnen CAM, Klein Kranenbarg E, Mulder-Stapel AA, Hermans J, van de Velde CJH, van Krieken JHJM, et al., manuscript submitted], we did a stratified analysis of all data to minimize possible therapy related effects. Neutrophils and T cells were decreased in the radiotherapy group. There were no differences between both groups in numbers of mast cell, eosinophils, NK cells and macrophages.

Statistics

Differences between groups were obtained using the unpaired Student's t-test. Relations between various parameters were analyzed using Χ2 -methods, Mann Whitney tests and bivariate Pearsons' correlation analysis. Univariate survival analyses of time to local recurrence, distant metastasis or death were performed using the Kaplan Meier method, with the time of surgery as the entry date. Differences in observed survival between groups were tested for statistical significance using log ranks tests. The variables with a significant impact in the univariate analysis (p < 0.05) were further examined using the Cox proportional hazards regression model; the forward step-wise elimination method was used for this multivariate analysis. Next, the prognostic value of the selected cell types was analyzed additional to the TNM classification and the presence of inflammatory infiltrate using the enter method. Data were analyzed using the SPSS software package (SPSS 9.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

All statistical analyses were stratified for randomization arm. At p < 0.05, differences were considered statistically significant.

Results

Peritumoral inflammatory infiltrate

The presence of extensive inflammatory infiltrate was associated with higher survival rates (p < 0.0001), lower distant recurrence rates (p < 0.0001) and lower local recurrence rates (p = 0.03) in the whole trial population (n = 1416, median follow-up = 19.6 months) (table 2). Cox regression revealed that the presence of inflammatory infiltrate has additional value next to the TNM classification with regards to the development of distant recurrence and survival (table 3).

Table 2.

Results of univariate log rank analyses for the risk on local recurrence, the risk on distant metastases and the survival for the presence of inflammatory infiltrate and eosinophilic granuloytes.

| inflammatory infiltrate | eosinophilic granulocytes | ||||||

| none/few | extensive | P | none/ few | moderate | extensive | P | |

| local recurrence rate | 6.9% | 3.4% | 0.03 | 7.4% | 4.8% | 2.8% | 0.10 |

| (2 year) | |||||||

| distant metastases | 23.8% | 8.2% | <0.0001 | 23.8% | 16.8% | 16.1% | 0.03 |

| rate (2 year) | |||||||

| cumulative survival | 79.1% | 92.0% | <0.0001 | 79.0% | 84.1% | 86.9% | 0.007 |

| (2 year) | |||||||

Median follow-up is 19.6 months, n = 1416.

Table 3.

Results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis for the risk on local recurrence, distant metastases and survival for the presence of inflammatory infiltrate and TNM classification.

| local recurrence | distant metastases | 2 year survival | ||||

| RR | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | |

| TNM I/II | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| TNM III/IV | 4.8 | 2.7-8.8 | 2.8 | 2.2-3.7 | 5.8 | 4.1-8.3 |

| none/few inflammatory cells | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| extensive inflammatory infiltrate | 1.7 | 0.7-4.3 | 2.6 | 1.5-4.6 | 2.4 | 1.2-4.5 |

Median follow up is 19.6 months, n = 1416. RR: relative risk, Cl: confidence interval

Eosinophilic granulocytes

The presence of a high number of eosinophilic granulocytes, as semiquantitatively scored by the PRC, was significantly associated with higher survival rates (p = 0.007) and lower distant recurrence rates (p = 0.03) in the whole trial population (table 2). Multivariate analysis showed that the presence of eosinophilic granulocytes did not have any additional prognostic value next to inflammatory infiltrate nor TNM classification.

Correlation of cell types mutual, with inflammatory infiltrate

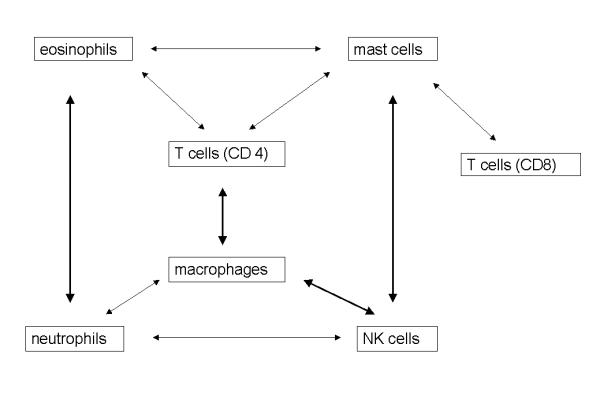

For all cell types there was a strong correlation between their intratumoral and their peritumoral presence (table 4). The strongest relations were found between the numbers eosinophils and neutrophils, between macrophages and NK cells, between mast cells and NK cells, and between T cells (CD3) and macrophages (figure 1). All correlations are positive.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients for all cell types (Pearsons' analysis).

| eo p (p) | NF i (i) | NF p (p) | MC i (i) | MC p (p) | MΦ i (i) | NK i (i) | NK p (p) | CD3 i | CD3 p | CD4 i | CD4 p | CD8 i | CD8 p | |

| 0.26* | 0.37* | 0.27* | 0.17 | 0.17 | Eo i (i) | |||||||||

| 0.21 | 0.24* | 0.23* | 0.18 | Eo p (p) | ||||||||||

| 0.63* | 0.19 | 0.16 | NF i | |||||||||||

| 0.19 | NF p (p) | |||||||||||||

| 0.29* | 0.17 | 0.27* | 0.19 | 0.25* | 0.22* | MC i (i) | ||||||||

| 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.22* | 0.24* | MC p | ||||||||||

| 0.25* | 0.30* | 0.19 | 0.22 | MΦ i | ||||||||||

| 0.20 | NK i | |||||||||||||

| 0.17 | NK p | |||||||||||||

| 0.38* | 0.36* | 0.30* | 0.16 | CD3 i | ||||||||||

| 0.23* | 0.26* | CD3 p | ||||||||||||

| 0.65* | CD4 i | |||||||||||||

| CD4 p | ||||||||||||||

| 0.76* | CD8 i |

Only the significant correlations are shown. The marked correlation coefficients (*) are significant with p values < 0.001, other correlations are significant at a level of p < 0.05. (n = 160). Eo:eosinophilic granuloytes, NF:neutrophilic granulocutes, MC:mast cells, MΦ:macrophages, p: peritumoral, i: intratumoral

Figure 1.

Mutual relations between the inflammatory cell types regardless of location. Relations depicted by bold arrows show a significant relationship with r ≥ 0.25. T-cells (CD3, not shown) show significant relations with all cell types (most strongly to CD4 and macrophages r ≥ 0.25).

The amount of inflammatory infiltrate was significantly correlated with the high numbers of peritumoral mast cells (p = 0.006), peritumoral macrophages (p = 0.01), T cells (CD3, intratumoral p = 0.007 and peritumoral p = 0.02) and cytotoxic T cells (CD8, peritumoral: p = 0.003, intratumoral: p < 0.05).

Local recurrence

Six cell types were significantly associated with local recurrence (Table 5). The presence of high numbers of intratumoral NK cells, macrophages and T cells (CD4) decreased the chance of local recurrence. Peritumoral presence of high numbers of mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils was also important in the univariate analysis. Cox regression analysis (table 6) selected only peritumoral mast cells as marginally significant related to local recurrence. When we analyze the influence of TNM classification together with the presence of mast cells, both parameters did have a marginal effect.

Table 5.

Results of univariate log rank analyses for the risk on local recurrence, the risk on distant metastases and the survival.

| local recurrence % | distant metastases % | cumulative survival % | |||||||||||

| (2 year) | (2 year) | (2 year) | |||||||||||

| cell type | none/few | moderate | many | p-value | none/few | moderate | many | p-value | none/few | moderate | many | p-value | |

| eosinophils | |||||||||||||

| intratumoral | 18 | 26 | 34 | 0.45 | 30 | 54 | 56 | 0.08 | 72 | 67 | 62 | 0.94 | |

| peritumoral | 42 | 24 | 14 | 0.007* | 62 | 48 | 35 | 0.009* | 56 | 65 | 83 | 0.0008* | |

| neutrophils | |||||||||||||

| intratumoral | 35 | 23 | 23 | 0.42 | 46 | 49 | 47 | 0.85 | 61 | 68 | 73 | 0.66 | |

| peritumoral | 44 | - | 22 | 0.02* | 52 | - | 48 | 0.88 | 48 | - | 72 | 0.19 | |

| mast cells | |||||||||||||

| intratumoral | 42 | 23 | 20 | 0.17 | 65 | 47 | 39 | 0.08 | 45 | 74 | 71 | 0.006* | |

| peritumoral | 44 | 18 | 15 | 0.007* | 86 | 38 | 21 | <0.0001* | 43 | 78 | 73 | <0.0001* | |

| macrophages | |||||||||||||

| intratumoral | 41 | 25 | 9 | 0.03* | 63 | 50 | 28 | 0.03* | 56 | 70 | 75 | 0.006* | |

| peritumoral | 27 | 21 | 17 | 0.70 | 54 | 31 | 20 | 0.007* | 70 | 68 | 67 | 0.50 | |

| NK cells | |||||||||||||

| intratumoral | 36 | - | 20 | 0.03* | 50 | - | 47 | 0.58 | 57 | - | 73 | 0.15 | |

| peritumoral | 27> | - | 23 | 0.65 | 52 | - | 40 | 0.22 | 68 | - | 68 | 0.87 | |

| T cells (CD3) | |||||||||||||

| intratumoral | 35 | 29 | 13 | 0.08 | 76 | 42 | 32 | <0.0001* | 57 | 67 | 75 | 0.002* | |

| peritumoral | 25 | 23 | 25 | 0.67 | 63 | 41 | 47 | 0.02* | 60 | 70 | 69 | 0.17 | |

| CD4 T cells | |||||||||||||

| intratumoral | 33 | 31 | 10 | 0.01* | 48 | 47 | 46 | 0.55 | 66 | 60 | 78 | 0.21 | |

| peritumoral | 36 | 28 | 14 | 0.10 | 54 | 53 | 46 | 0.90 | 66 | 65 | 70 | 0.51 | |

| CD8 T cells | |||||||||||||

| intratumoral | 34 | 22 | 22 | 0.19 | 71 | 42 | 37 | 0.0005* | 58 | 73 | 69 | 0.01* | |

| peritumoral | 27 | - | 20 | 0.11 | 58 | - | 19 | 0.002* | 60 | - | 86 | 0.05 | |

The marked cell types (*) show a significant correlation with prognosis. Median follow up is 35.4 months, n = 160

Table 6.

Results of Cox regression analysis for local recurrence, distant metastases and survival.

| tested variables | cell types | cell types/ | TNM / | ||

| inflamm. | infiltrate | ||||

| RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | ||

| local recurrence | peritumoral mast cells | ||||

| - none/few | 3.7 | 1.1 -12.8 | 1.9 | 0.5-7.1 | |

| -moderate | 1.3 | 0.4- 4.4 | 0.9 | 0.3-3.1 | |

| - many | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| inflammatory infiltrate | |||||

| -none/few | - | 1.0 | |||

| -extensive | 0.3 | 0.0-2.2 | |||

| n = 148 | TNM | ||||

| 33 events | - I/I I | - | 1.0 | ||

| -III/IV | 2.4 | 0.9-6.1 | |||

| distant | peritumoral mast cells | ||||

| metastases | - none/few | 4.5 | 1.6-12.2 | 2.5 | 1.2-5.8 |

| - moderate | 1.1 | 0.4-2.9 | 0.9 | 0.3-2.3 | |

| - many | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| intratumoral T cells (CD3) | |||||

| - none/few | 3.2 | 1.5-6.8 | 2.6 | 1.2-5.8 | |

| -moderate | 2.0 | 0.9-4.1 | 1.8 | 0.8-3.8 | |

| - many | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| inflammatory infiltrate | |||||

| - none/few | - | 1.0 | |||

| - extensive | 1.0 | 0.4-2.9 | |||

| n = 159 | TNM | ||||

| 65 events | -I/II | - | 1.0 | ||

| -III/IV | 4.4 | 1.9-9.9 | |||

| survival | peritumoral eosinophils | ||||

| - none/few | 3.6 | 1.5-8.7 | 3.0 | 1.2-7.2 | |

| -moderate | 2.8 | 1.2-6.6 | 2.1 | 0.9-5.1 | |

| - many | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| peritumoral mast cells | |||||

| - none/few | 2.9 | 1.2-6.8 | 1.4 | 0.6-3.4 | |

| -moderate | 0.8 | 0.4-1.9 | 0.6 | 0.3-1.4 | |

| - many | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| inflammatory infiltrate | |||||

| - none/few | - | 1.0 | |||

| - extensive | 1.0 | 0.4-2.5 | |||

| n = 136 | TNM | ||||

| 59 events | - I/II | - | 1.0 | ||

| - III/IV | 2.9 | 1.4-6.2 | |||

Cell types are included in the multivariate analysis if their p-value was less than 0.05 in the univariate analysis (table 3). Cell types are reported here and included in the multivariate analysis with TNM classification and inflammatory infiltrate, if they were significant in the Cox' regression of the cell types forward step-wise applied.

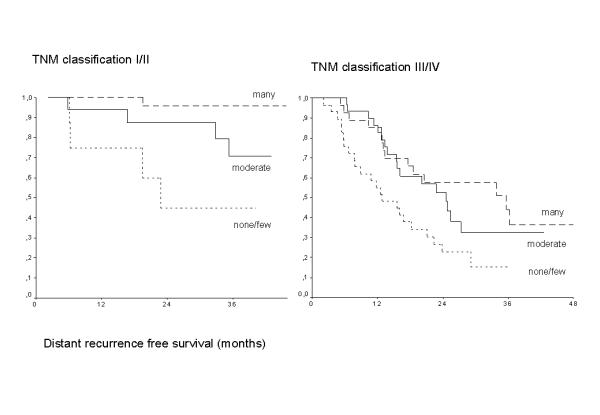

Distant recurrence

Four cell types were correlateed with the development of distant metastases (table 5). Both the peritumoral and the intratumoral presence of a high number of macrophages and T cells (CD3, as well as the CD8 subset) were a prognostic good sign and had a decreased risk on distant metastases. Presence of many peritumoral eosinophils and mast cells decreased the chance of distant recurrence. Cox regression (table 6) selected both peritumoral mast cells and intratumoral T cells as being the most important. The amount of intratumoral T cells has independent prognostic value additional to the TNM classification, see also figure 2.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the development of distant recurrence showing the TNM independent effect of the three categories of intratumoral T cells (CD3), p = 0.0004

Survival analysis

In predicting survival, intratumoral macrophages, T cells (CD3 and CD8), mast cells and peritumoral mast cells and eosinophils are significant (table 5). Cox regression (table 6) showed that peritumoral eosinophils and mast cells are important for survival. The amount of peritumoral eosinophils has independent prognostic value additional to the TNM classification.

Tumor characteristics

The amount of peritumoral T helper cells (CD4) and eosinophils was correlated with the depth of tumor invasion (p = 0.01 and p = 0.02), as well as with the amount of intratumoral T cells (CD3, p = 0.04). Other cell types did not have an association with depth of tumor invasion. There was a clear relation with the lymph node status (positive/negative) and the amount of peritumoral eosinophils (p = 0.02), mast cells (p < 0.001), macrophages (intratumoral p = O.OS, peritumoral p = 0.004) and T cells (intratumoral, p = 0.02). The presence of distant metastases at the time of surgery was not associated with any cell type. Mucinous carcinomas showed less peritumoral neutrophil, macrophage and T cell infiltrate. There was no association of any cell type with the differentiation grades, except for the presence of CD4 positive cells (p = 0.02).

The numbers of peritumoral eosinophils, and infra- and peritumoral macrophages and mast cells were related to the stages in the TNM classification.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to evaluate the interaction between the specific and general inflammatory reaction and the relation with prognosis of rectal cancer patients. We showed that although a large specific anti-tumor response reflected by T cells, protects against distant metastases, the effects on patient survival and local recurrence are less important compared to the effects of the nonspecific inflammatory response. The most important representatives of the nonspecific inflammatory response are mast cells, eosinophils and NK cells, less important are the neutrophils and macrophages. In contrast to earlier studies [16,18] in which the presence of mast cells has been described as a prognostic poor or indifferent factor, we found that the presence of many peritumoral mast cells is a prognostic good sign. An explanation for these contradictionary results may be the method of determination of mast cells. While in the published studies the presence of mast cells was determined by histochemical procedures, nowadays specific antibodies are in use. This is confirmed by the finding of Nielsen et al [17], who used the same tryptase antibody as we did and also found a positive influence of many mast cells on prognosis. Our data are in accordance with data obtained in animal models. Mast cell deficient mice show an increased tumor incidence compared to normal mice after treatment with carcinogens. This increased tumor incidence was not seen when the carcinogen was given after bone marrow transplantation to overcome the mast cell deficiency [25].

The peritumoral presence of mast cells is the most important prognostic factor for local recurrence in the univariate analysis. The strong relation between the presence of peritumoral mast cells and inflammatory infiltrate and the fact that in the multivariate analysis the presence of inflammatory infiltrate is no longer significant when compared to mast cell infiltrate, suggests that this cell type is the most important cell type within this infiltrate. This is not in contradiction with the original definition of inflammatory or lymphoid or lymphocytic infiltrate by Jass [26]: "stromal reaction in which lymphocytes are present as a part of a mixed chronic infiltrate and not necessarily in large numbers".

However, within the inflammatory infiltrate other cell types are important as well, like eosinophils and NK cells. The close interactions of mast cells and eosinophils are firmly established [27,28], but there are also functional relationships between mast cells and T cells [29], eosinophils and T cells [30], mast cells and macrophages [5].

In the multivariate analysis for the development of distant metastases both the specific immune response (T cells) and the nonspecific response (mast cells) demonstrated prognostic value. Comparing this with the TNM classification, the presence of T cells had independent prognostic value additional to this classification. It is not surprising that the specific immune response, which is reflected by the presence of T cells in the tumor, but in reality is a systemic reaction against tumor cells, has influence on the development of distant metastases. Surprisingly, the nonspecific response, represented by the mast cells in the selection and in the whole trial population the eosinophilic granulocytes, are also able to influence the development of distant metastases.

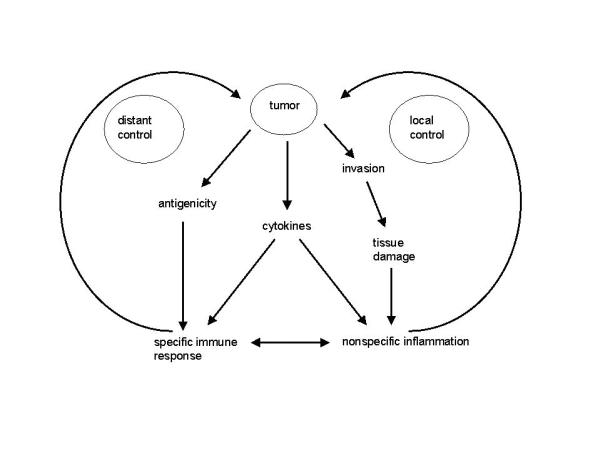

On the basis of our data we propose a model for the host response in rectal cancer, in which there is an interaction between the specific and the nonspecific inflammatory reaction (figure 3). In this model we assume that tumors can evoke a host response in three different ways, altered antigenicity, cytokine production and tissue damage. It is likely that these different mechanisms are integrated. The specific immune response is directed against and attracted by the altered antigenicity of the tumor cells [8], while the nonspecific response might be a reaction to the tissue damage caused by tumor invasion. The presence of neutrophilic granulocytes is indicative of this phenomenon. Both the specific and the nonspecific immune response can be evoked by cytokine production by the tumor and its microenvironment [31-33].

Figure 3.

Model of specific and nonspecific host response. The specific immune response are the T cells, the nonspecific immune response is formed by eosinophilic and neutrophilic granulocytes, mast cells, macrophages and NK cells.

These three mechanisms are responsible for the development of the host response, which consists of a specific and a nonspecific immune reaction. Both reactions are necessary for the establishment of the host response, which is demonstrated by the close correlations of the different cell types in our study as well as from literature data.

The peritumoral presence of the nonspecific infiltrate is mainly involved in local control of the tumor process, as gathered from the clear relation between mast cells and local recurrence, whereas the specific response is mainly concerned with the occurrence of hematogenous metastases. The nonspecific infiltrate is indirectly linked to the prevention of distant metastases by the interactions with the specific response, as well as by the improved local control.

List of abbreviations

HPF: high power fields,

i: intratumoral,

p: peritumoral,

PRC: Pathology Review Committee,

TME: Total Mesorectal Excision,

TNM: Tumor Node Metastases

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/backmatter/1471-2407-1-7-b1.pdf

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Pathology Review Committee

E. Bloemena, Vrije Universiteit, J. Offerhaus, Academisch Medisch Centrum, M.F.L. van Velthuysen, B. Loftus, Antoni van Leeuwenhoekhuis, Amsterdam, J. Los, St.lgnatius Ziekenhuis, Breda, P.J. Westenend, PA laboratorium, Dordrecht, H.M. Peters, I.W.N. Tan-Go, Stichting PAMM, Eindhoven, A.J.K. Grond, Lab. Volksgezondheid Friesland, Leeuwarden, J.W. Arends, Academisch Ziekenhuis, Maastricht, A. Maes, J.C. Verhaar, Stichting Pathan, Rotterdam, A. van der Wurff, Laboratorium Centraal Brabant, Tilburg; the Netherlands

Competing interests

None declared

Contributor Information

Iris D Nagtegaal, Email: I.Nagtegaal@pathol.azn.nl.

Corrie AM Marijnen, Email: marijnen@lumc.nl.

Elma Klein Kranenbarg, Email: KleinKrane@lumc.nl.

Adri Mulder-Stapel, Email: a.a.mulder-stapel@lumc.nl.

Jo Hermans, Email: Johermans@nu.ac.th.

Cornelis JH van de Velde, Email: velde@lumc.nl.

J Han JM van Krieken, Email: J.vanKrieken@pathol.azn.nl.

References

- Caruso RA, Speciale G, Inferrera C. Neutrophil interaction with tumour cells in small early gastric cancer: ultrastructural observations. Histol Histopathol. 1994;9:295–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson L, Adell G, Boeryd B, Sjogren F, Sjodahl R. Infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells into primary colorectal carcinomas: an immunohistological analysis. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:374–380. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JL, Akhter J, Adams WJ, Morris DL. Histamine content in colorectal cancer. Are there sufficient levels of histamine to affect lymphocyte function? Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23:224–227. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(97)92388-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiniger CJ. Mast cells and tumor-associated angiogenesis. Chem Immunol. 1995;62:239–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbous MK, North SM, Haney L, Tipton DA, Nicolson GL. Effects of mast cell-macrophage interactions on the production of collagenolytic enzymes by metastatic tumor cells and tumor-derived and stromal fibroblasts. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1995;13:33–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00144016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadou V, Koutsilieris M. Mast cell - tumor cell interactions: for or against tumour growth and metastasis ? Anticancer Res. 1997;17:1541–1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcetti R, Viel A, Doglioni C, Russo A, Guidoboni M, Capozzi E, et al. High prevalence of activated intraepithelial cytotoxic T lymphocytes and increased neoplastic cell apoptosis in colorectal carcinomas with microsatellite instability. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1805–1813. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65436-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedegebuure PS, Eberlein TJ. The role of CD4+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in human solid tumors. Immunol Res. 1995;14:119–131. doi: 10.1007/BF02918172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropponen KM, Eskelinen MJ, Lipponen PK, Alhava E, Kosma VM. Prognostic value of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 1997;182:318–324. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199707)182:3<318::AID-PATH862>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espi A, Arenas J, Garcia-Granero E, Marti E, Lledo S. Relationship of curative surgery on natural killer cell activity in colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:429–434. doi: 10.1007/BF02054059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coca S, Perez-Piqueras J, Martinez D, Colmenarejo A, Saez MA, Vallejo C, et al. The prognostic significance of intratumoral natural killer cells in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79:2320–2328. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970615)79:12<2320::AID-CNCR5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner JM, Jarvis LR, Whitehead R. The cellular response to human colonic neoplasms: macrophage numbers. J Pathol. 1983;139:97–103. doi: 10.1002/path.1711390202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins CA, Hatton WJ, McKerr G, Harvey D, Carson J, Hannigan BM. Macrophages and apoptotic cells in human colorectal tumours. Biologicals. 1996;24:329–332. doi: 10.1006/biol.1996.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DJ, O'Brien P. Cytotoxicity of cancer patient's macrophages for tumor cells. Cancer. 1982;50:498–502. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820801)50:3<498::aid-cncr2820500319>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachter J, Stein M, Lichtig C, Eidelman S, Munichor M. Mast cells in colorectal neoplasias and premalignant disorders. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:290–293. doi: 10.1007/BF02055605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher ER, Paik SM, Rockette H, Jones J, Caplan R, Fisher B. Prognostic significance of eosinophils and mast cells in rectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen HJ, Hansen U, Christensen IJ, Reimert CM, Brünner N, Moesgaard F, et al. Independent prognostic value of eosinophil and mast cell infiltration in colorectal cancer tissue. J Pathol. 1999;189:487–495. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199912)189:4<487::AID-PATH484>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretlow TP, Keith EF, Cryar AK, Bartolucci AA, Pitts AM, Pretlow TG, et al. Eosinophil infiltration of human colonic carcinomas as a prognostic indicator. Cancer research. 1983;43:2997–3000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satomi A, Murakami S, Ishida K, Hashimoto T, Sonoda M. Significance of increased neutrophils in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 1995;34:69–73. doi: 10.3109/02841869509093641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jass JR, Love SB, Northover JMA. A new prognostic classification of rectal cancer. Lancet. 1987;1:1303–1306. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)90552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Quay N, Cerottini JP, Albe X, Saraga E, Givel JC, Caplin S. Prognosis in Dukes'B colorectal carcinoma: The Jass classification revisited. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:588–592. doi: 10.1080/110241599750006514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abulafi AM, Williams NS. Local recurrence of colorectal cancer: the problems, mechanisms, management and adjuvant therapy. Br J Surg. 1994;81:7–19. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiteijn E, Klein Kranenbarg E, Steup WH, Taat CW, Rutten HJT, Wiggers T, et al. Total mesorectal excision (TME) with or without preoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of primary rectal cancer - Prospective randomised trial with standard operative and histopathological techniques. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:410–420. doi: 10.1080/110241599750006613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagtegaal ID, Klein Kranenbarg E, Hermans J, van de Velde CJH, van Krieken JHJM, Pathology Review Committee Pathology data in the central database of multicenter randomized trials need to be based on pathology reports and controlled by trained quality managers. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1771–1779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanooka H, Kitamura Y, Sado T, Tanaka K, Nagase M, Kondo S. Evidence for involvement of mast cells in tumor suppression in mice. J NatI Cancer Inst. 1982;69:1305–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jass JR, Ajioka Y, Allen JP, Chan YF, Cohen RJ, Nixon JM, et al. Assessment of invasive growth pattern and lymphocytic infiltration in colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 1996;28:543–548. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das AM, Flower RJ, Perretti M. Resident mast cells are important for eotaxin-induced eosinophil accumulation in vivo. Leukocyte Biol. 1998;64:156–162. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Schaffer F, Temkin V, Malamud V, Feld S, Zilberman Y. Mast cells enhance eosinophil survival in vitro: Role of TNF-α and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Immunol. 1998;160:5554–5562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekori YA, Metcalfe DD. Mast cell-T cell interactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:517–523. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewe M, Czech W, Morita A, Werfel T, Klammer M, Kapp A, et al. Human eosinophils produce biologically active IL-12: Implications for control of T cell responses. J Immunol. 1998;161:415–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartour E, Fridman WH. Cytokines and cancer. Intern Rev Immunol. 2000;16:683–704. doi: 10.3109/08830189809043014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages F, Vives V, Sautes-Fridman C, Fossiez F, Berger A, Cugnenc PH, et al. Control of tumor development by intratumoral cytokines. Immunol Lett. 1999;68:135–139. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2478(99)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piancatelli D, Romano P, Sebastiani P, Adorno D, Casciani CU. Local expression of cytokines in human colorectal carcinoma: evidence of specific interleukin-6 gene expression. J Immunotherapy. 1999;22:25–32. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]