Abstract

Grain size and shape are important components determining rice grain yield, and they are controlled by quantitative trait loci (QTLs). Here, we report the cloning and functional characterization of a major grain length QTL, qGL3, which encodes a putative protein phosphatase with Kelch-like repeat domain (OsPPKL1). We found a rare allele qgl3 that leads to a long grain phenotype by an aspartate-to-glutamate transition in a conserved AVLDT motif of the second Kelch domain in OsPPKL1. The rice genome has other two OsPPKL1 homologs, OsPPKL2 and OsPPKL3. Transgenic studies showed that OsPPKL1 and OsPPKL3 function as negative regulators of grain length, whereas OsPPKL2 as a positive regulator. The Kelch domains are essential for the OsPPKL1 biological function. Field trials showed that the application of the qgl3 allele could significantly increase grain yield in both inbred and hybrid rice varieties, due to its favorable effect on grain length, filling, and weight.

Keywords: QTL mapping, positional cloning, Oryza sativa L.

Grain number, panicle number, and grain weight are three important components of grain yield of rice (Oryza sativa L.). When grain number per panicle and panicle number per plant reach an ideal level, improvement of grain weight plays a key role in further yield increase in rice-breeding programs (1). Grain weight is largely determined by grain size, which is specified by its three dimensions (length, width, and thickness) and the degree of filling. Currently, 1,000-grain weight of commercial rice varieties is usually 25∼35 g. To date, several quantitative trait loci (QTLs) that affect rice grain size and/or shape have been cloned from different rice germplasms. GS3 (2–4) and DEP1 (5, 6), two QTLs affecting rice grain length, function as negative factors; however, their homolog in Arabidopsis, AGG3, has been found to be an atypical heterotrimeric G protein γ-subunit that positively regulates organ size (7, 8). For grain width, GW2 (9) (encoding a RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase) and qSW5/GW5 (10, 11) have been reported as negative regulators, whereas GS5 (12) (encoding a putative serine carboxypeptidase) and GW8 (13) (encoding a transcription factor with SBP domain) are positive regulators. These loci, except GW2, have been artificially selected in rice-breeding programs. To realize the goal of breeding superrice varieties, it is well worth it to explore novel genetic loci that regulate grain shape and weight in rice germplasms (14). Here we report the QTL mapping, positional cloning, and functional characterization of qgl3, a rare allele that shows an extraordinary effect on rice grain length and grain weight, which can be applied in breeding new elite varieties to significantly improve rice grain yield.

Results and Discussion

Map-Based Cloning of qGL3.

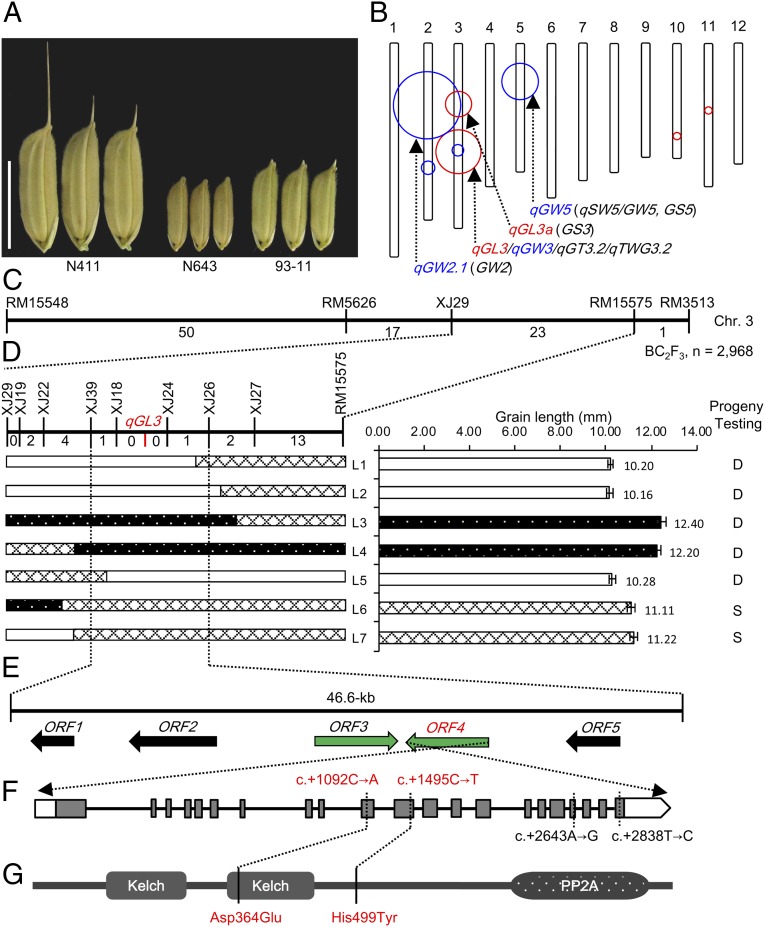

By screening more than 7,000 germplasms, we identified an extra large-grain japonica accession N411 (1,000-grain weight = 72.13 ± 2.32 g; Fig. 1A). To dissect the genetic basis of the large grain size of N411, we carried out a QTL analysis in an F2 population derived from a cross between N411 and a polymorphic small-grain indica variety N643 (1,000-grain weight = 17.80 ± 0.82 g; Fig. 1A). Twenty-three QTLs affecting grain size and/or weight were mapped in this population, including four for grain length, four for width, seven for thickness, and eight for weight (Table S1). Among them, three major loci, qGL3a, qGW2.1, and qGW5, were mapped at the same locations of four reported genes, GS3, GW2, qSW5/GW5, and GS5, respectively (Fig. 1B; Table S1). The allelic sequencing data of these four genes confirmed allele variances in N411 and N643 (Table S2). Importantly, we identified a major grain length QTL, qGL3, on the long arm of chromosome 3 (Fig. 1B), explaining 38.38% phenotypic variation of grain length, 27.99% of grain weight, 11.89% of grain thickness, and 5.96% of grain width (Table S1). The recessive allele from N411, qgl3, contributes positively to these traits. The result indicates that N411 pyramids at least four known positive grain-size loci (gw2, gs3, gw5, and GS5) and a major grain length locus (qgl3) to form extra-large grains.

Fig. 1.

Map-based cloning of qGL3. (A) Parental grains used for QTL analysis and fine-mapping. (Scale bar: 10 mm.) (B) QTLs affecting grain length and width identified in the N411 × N643 F2 population. Red and blue circles show grain length and width, respectively. Circle sizes reflect their effects on phenotypic variations. The major loci, including three known loci (shown in bracket) and the qGL3 locus, are indicated by arrows. (C) A fine-linkage map generated by analyzing 2,968 N411 × 93-11 BC2F3 segregating plants. The recombinant numbers are given between markers. (D) High-resolution linkage analysis of phenotypes and marker genotypes. White bars represent chromosomal segments for 93-11 homozygote, black with spots for N411 homozygote, and grille for heterozygote, respectively. Progeny testing was used to confirm the genotypes at the qGL3 locus. S, segregation; D, desegregation. (E) Predicted ORFs based on the Nipponbare genome sequence. The horizontal arrows represent predicted five ORFs (ORF1, LOC_Os03g44460; ORF2, LOC_Os03g44470; ORF3, LOC_Os03g44484; ORF4, LOC_Os03g44500; and ORF5, LOC_Os03g44510). (F) The gene structure of ORF4. Empty boxes refer to 5′ and 3′ UTRs, gray boxes to exons, and the lines between boxes to introns. The SNPs in the OsPPKL1N411 are shown by dashed lines; SNP1, c.+1092C→A; SNP2, c.+1495C→T; SNP3, c.+2643A→G; SNP4, c.+2838T→C. (G) The Kelch domains and the PP2A domain predicted in the protein encoded by ORF4. Solid lines show the positions of two amino acid transitions.

A high-quality elite indica variety, 93-11 (1,000-grain weight = 30.08 ± 1.34 g; Fig. 1A), was used as a recurrent parent to further validate and disassemble qGL3. qGL3 was confirmed and mapped to an interval between simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers RM15551 and RM15578 with a high log-likelihood value (limit of detection = 68.8) and explained 95.57% phenotypic variation in a N411 × 93-11 BC2F2 population (Fig. S1). A total of 2,968 BC2F3 individuals derived from four heterozygous N411 × 93-11 BC2F2 plants were screened for recombinants within the target region defined by SSR markers RM15548 and RM3513 (Fig. 1C), outward to markers RM15551 and RM15578, respectively. High-resolution linkage analysis narrowed qGL3 to a 46.6-kb region between insertion and deletion (InDel) markers XJ39 and XJ26 (Fig. 1D; Table S3). In this region, there are five predicted ORFs according to the Nipponbare genome sequence (annotated by Michigan State University Rice Genome Annotation Project Release 7.0; Fig. 1E).

Based on RT-PCR analysis and expressed sequence tag (EST) information, we found that only ORF3 and ORF4 were expressed, whereas ORF1 and ORF2 encoding retrotransposon proteins and ORF5 encoding a transposon were not expressed in rice. Sequence comparison of these two expressed ORFs between 93-11 and N411 revealed four SNPs in the ORF4. SNP1, a single nucleotide transition from C (93-11) to A (N411) (c.+1092C→A), is present in the 10th exon of the ORF4, and SNP2, a single nucleotide transition from C (93-11) to T (N411) (c.+1495C→T), in the 11th exon (Fig. 1F). These two transitions cause amino acid residue changes from aspartate to glutamate (Asp364Glu) and histidine to tyrosine (His499Tyr), respectively (Fig. 1G). SNP3 (c.+2643A→G, in the 18th exon) and SNP4 (c.+2838T→C, in the 21st exon) do not cause amino acid residue changes (Fig. 1F). No difference in the ORF3 sequence was identified between 93-11 and N411. Furthermore, RT-PCR analyses showed no expressional difference in young panicles between 93-11 and its near-isogenic line (NIL)-qgl3 (Fig. S2) that carries a ∼113-kb segment, including the N411 qgl3 allele in the 93-11 background. Therefore, ORF4 was most likely the candidate gene for qGL3. The ORF4 encodes a putative type 2A phosphatase (PP2A), and it is therefore designated as OsPPKL1, which belongs to a small gene family because there are three protein phosphatases with Kelch-like repeat domain (PPKL) members in O. sativa, four in Arabidopsis thaliana, two in Brachypodium distachyon, three in Zea mays, three in Sorghum bicolor, and three in Setaria italica. Sequence alignment of these plant homologs showed that the amino acid transition (Asp364Glu) caused by SNP1 in OsPPKL1N411 occurs in a conserved AVLDT motif of the second Kelch domain (Fig. 1G), whereas the transition (His499Tyr) caused by SNP2 occurs in a nonconserved region (Fig. S3A).

Confirmation of OsPPKL1 as qGL3.

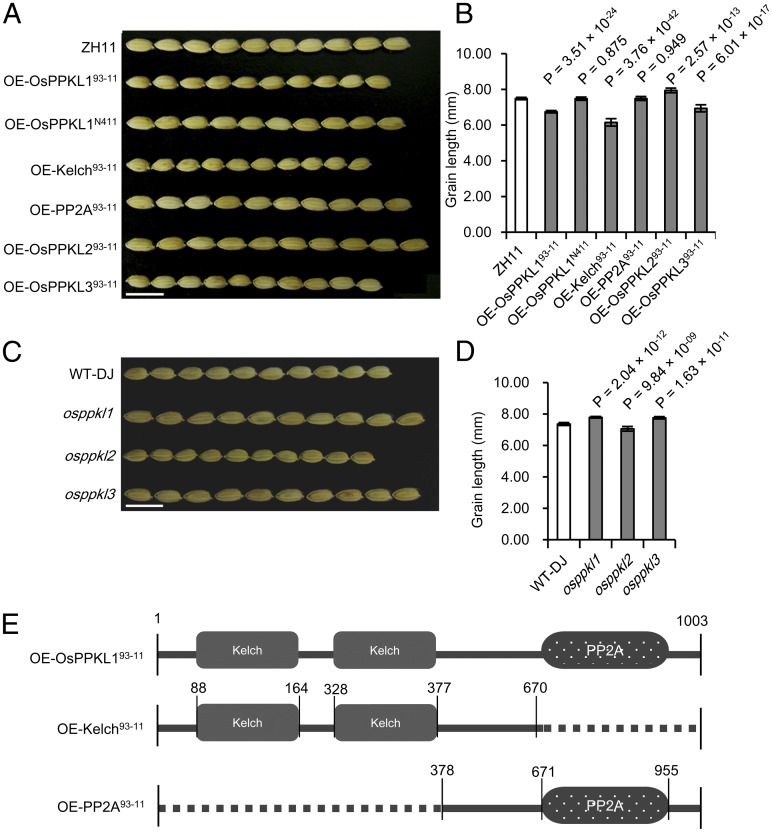

To confirm that OsPPKL1N411 is qgl3 and to understand its functional nature, we overexpressed (OE) OsPPKL193-11 and OsPPKL1N411, respectively, in a japonica variety, Zhonghua 11 (ZH11), which has a relatively short grain. We observed a decrease in grain length in the OE-OsPPKL193-11 transgenic plants (T1) compared with the control ZH11 (Fig. 2 A and B), whereas no difference in grain length was observed between the OE-OsPPKL1N411 (T1) and ZH11 (Fig. 2 A and B), suggesting that OsPPKL193-11 plays an inhibitory function in regulating the grain length, and the amino acid transition in OsPPKL1N411 abolishes its inhibitory role. Accordingly, the transfer DNA (T-DNA) insertion mutant of OsPPKL1, osppkl1 (3D-50056.R, created using an O. sativa L. ssp. japonica variety, Dongjin) (15, 16), exhibits longer grains compared with its wild type (Fig. 2 C and D). To further understand the inhibitory function of OsPPKL1, we overexpressed the Kelch domains and the PP2A domain of OsPPKL193-11 in ZH11, respectively (Fig. 2E). The OE-Kelch93-11 produced shorter grains compared with ZH11, and even shorter than the OE-OsPPKL193-11, whereas the OE-PP2A93-11 produced similar grains to ZH11 (Fig. 2 A and B). These results suggest that the inhibitory regulation effect of OsPPKL193-11 results from its Kelch domains. The Kelch domain has been reported to represent one β-sheet blade, and several repeats are able to interact to form a β-propeller (17). In rice, LARGER PANICLE (LP) encoding a Kelch repeat-containing F-box protein was reported to play a negative role in regulating plant architecture, particularly panicle architecture (18). In this study, we also found that the Kelch domains in OsPPKL193-11 play a negative regulation role in forming grain length.

Fig. 2.

Functional analysis of OsPPKLs. (A) Grains of the transgenic plants (T1) and ZH11. (Scale bar: 10 mm.) (B) Comparison of the grain length between ZH11 and the transgenic plants in A. P values from a t test of the transgenic plants against ZH11 were indicated. (C) The grains of OsPPKL knockout mutants in the Dongjin background. (D) Comparisons of the grain length of the mutant plants. P values from a t test of the mutant against Dongjin were indicated. (E) Schematic representation of constructs for overexpressing different domains.

Sequence Polymorphisms of qGL3 in Rice Germplasms.

Ninety-four rice germplasms with abundant diversity in grain size were selected for sequencing a 3.6-kb genomic DNA fragment that covers the four mutation sites of the qgl3. We found only one variety, DT108 (grain length = 12.08 mm), with the same SNP1 as N411, whereas polymorphisms of SNP2, SNP3, and SNP4 are widely distributed in either japonica or indica varieties (Table S4). By association analysis of the SNPs and InDel markers in the 3.6-kb region with grain length of the 94 germplasms (19), we found that SNP1 had a high contribution to grain length, whereas other polymorphic sites had no significant contributions to grain length (Table S5). These results indicate that the qgl3 is a rare allele in rice, and SNP1 is a functional mutation for long grain. The positive alleles of GS3 (2–4), qSW5/GW5 (10, 11), GS5 (12), and GW8 (13) for grain size are common in modern rice varieties, and the beneficial allele (qgl3) of qGL3 is rare, which is similar to GW2 (20). As a major pleitrophic QTL that has beneficial effects on grain length, grain thickness, grain width, and thousand-grain weight, qgl3 should be selected in rice-breeding. However, the rareness of the qgl3 allele in the collected accessions may reflect its recent occurrence, which needs to be addressed in the future.

Functions of Two OsPPKL1 Homologs.

The rice genome encodes other two OsPPKL1 homologs, OsPPKL2 (LOC_Os05g05240, identity = 57%) and OsPPKL3 (LOC_Os12g42310, identity = 89%). To understand whether they have similar functions to OsPPKL1, we first examined their expression profiles and levels. As shown in Fig. S3 B and C, all three OsPPKLs exhibit similar expression profiles in various rice organs, but OsPPKL2 expresses at a lower level than OsPPKL1 and OsPPKL3. We then overexpressed OsPPKL293-11 and OsPPKL393-11 in ZH11, respectively. Like OE-OsPPKL193-11, OE-OsPPKL393-11 transgenic lines also produced short grains, whereas OE-OsPPKL293-11 lines had long grains (Fig. 2 A and B). As expected, the T-DNA insertion mutants, osppkl3 (2C-10162.L) and osppkl2 (3A-06810.L) (15, 16), produce longer and shorter grains, respectively (Fig. 2 C and D). The phylogenetic analysis showed that OsPPKL2 and two Arabidopsis homologs AtBSU1 and AtBSL1 belong to one subgroup, and OsPPKL1 and OsPPKL3 to another subgroup (Fig. S3A). AtBSU1 and AtBSL1 were reported to be involved in brassinosteroid signaling to enhance cell elongation and division (21, 22). It is possible that the OsPPKL2 subgroup may also positively regulate cell elongation or division, whereas the OsPPKL1/3 subgroup plays a negative role.

Biological Roles of qgl3.

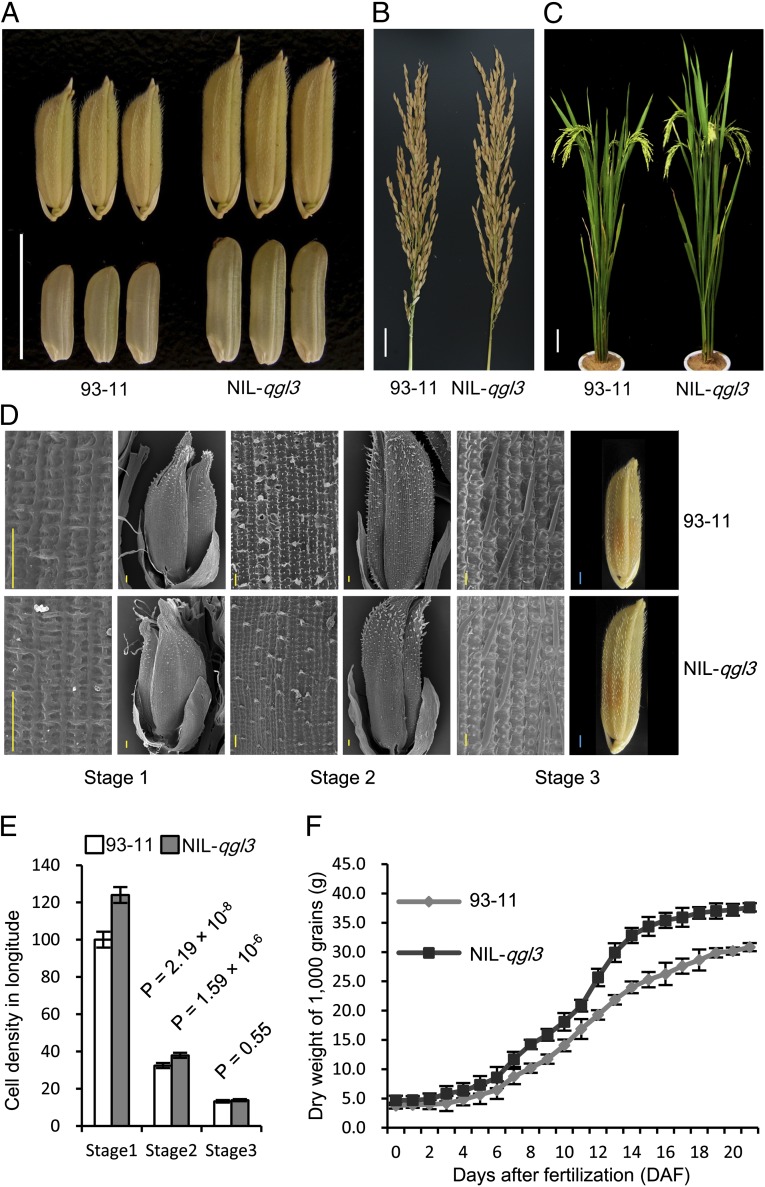

With a scanning electron microscope, we observed a higher cell density in the outer surface of glumes in NIL-qgl3 (OsPPKL1N411; Fig. 3 A–E) than that in 93-11 (OsPPKL193-11) at the early developing stages (spikelet = 2, and 5 mm) of spikelet, but no significant difference at the maturity stage (Fig. 3 D and E). Therefore, it is very likely that the long glumes of NIL-qgl3 result from an increase in cell numbers longitudinally, which is consistent with the observation that the NIL-qgl3 ovaries and grains are longer than those of 93-11 (Fig. S4). Comparison of the grain-filling rates between NIL-qgl3 and 93-11 by measuring dry weight of grains during grain-filling revealed that the dry weight of NIL-qgl3 was significantly higher than that of 93-11 from 8 d after fertilization (Fig. 3F), suggesting that the qgl3 allele has a great potential in breeding elite rice varieties.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of different traits between 93-11 and NIL-qgl3. (A) Grains of 93-11 and NIL-qgl3. (Scale bar: 10 mm.) (B) Panicles of 93-11 and NIL-qgl3. (Scale bar: 2 cm.) (C) Plants of 93-11 and NIL-qgl3. (Scale bar: 10 cm.) (D) Scanning electron and light microscope photos of glume outer surfaces of 93-11 and NIL-qgl3 spikelets at three stages. Stage 1, spikelet = 2 mm; stage 2, spikelet = 5 mm; stage 3, maturity. (Scale bars: yellow, 50 μm; blue, 1.0 mm.) (E) Cell density of glume outer surfaces of 93-11 and NIL-qgl3 spikelets at three stages. (F) Grain filling rate of 93-11 and NIL-qgl3 after fertilization, indicated by dry weight of 1,000 grains.

qgl3 Enhances Rice Yield Significantly.

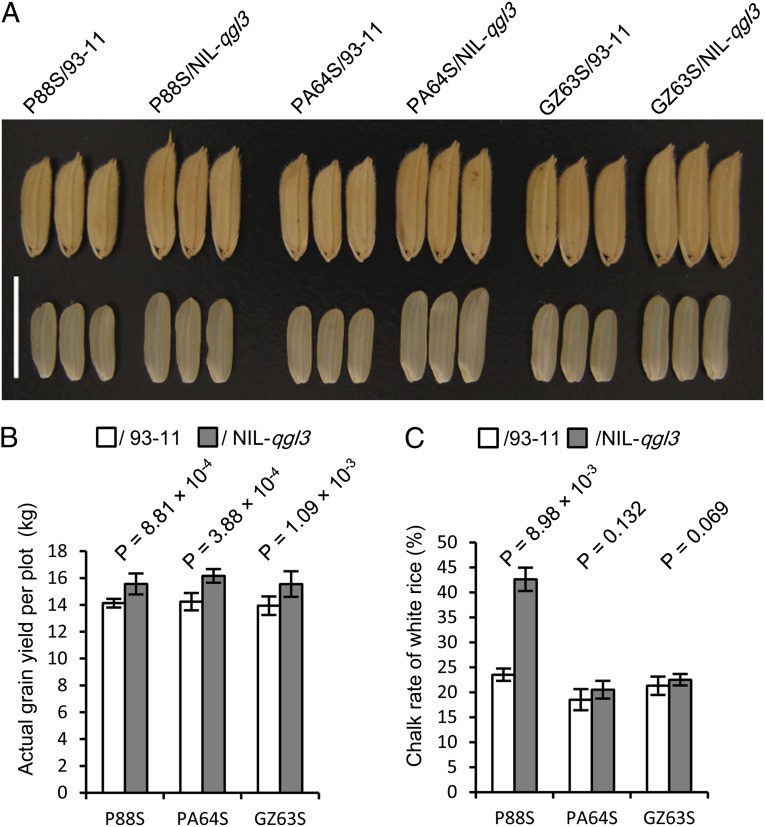

The grain yield and other agronomic traits of NIL-qgl3 were evaluated under field conditions. Compared with 93-11, NIL-qgl3 showed an increase of 16.20% in yield, resulting from increases of 19.68% in grain length, 1.15% in grain width, 8.25% in grain thickness, 37.03% in filled-grain weight, and 11.76% in panicle length (Table 1). No significant differences in grain number per panicle, tiller number per plant, days to heading, and plant height were observed between 93-11 and NIL-qgl3 (Fig. 3 A–C and Table 1). Therefore, the increase of grain yield in the NIL-qgl3 resulted from the improvement in grain weight. The chalk rate of white rice of NIL-qgl3 (23.14 ± 1.62, mean ± SD) was very similar to that of 93-11 (22.33 ± 1.32, mean ± SD). To explore the application of NIL-qgl3 in hybrid rice-breeding, we crossed 93-11 and NIL-qgl3 with three commercial photothermosensitive male sterile lines, P88S, Peiai64S (PA64S), and Guangzhan63S (GZ63S) to generate F1 seeds. Compared with P88S/93-11, PA64S/93-11, and GZ63S/93-11, the P88S/NIL-qgl3, PA64S/NIL-qgl3, and GZ63S/NIL-qgl3 produced significantly longer grains (Fig. 4A), resulting in an increase of 10.12∼13.48% grain yield in field trials (Fig. 4B). Except P88S/NIL-qgl3, PA64S/NIL-qgl3 and GZ63S/NIL-qgl3 showed similar chalk rates of white rice to PA64S/93-11 and GZ63S/93-11 (Fig. 4C). Therefore, the qgl3 allele can be applied in breeding elite varieties to improve rice grain production without sacrificing grain quality. In fact, the goal of breeding superelite rice with high yield and good quality could be realized by pyramiding production- and quality-related genes, such as ipa1 (23, 24), dep1 (5, 6), gs3 (2–4), gw2 (9), qsw5/gw5 (10, 11), GS5 (12), GW8 (13), wx (25), or alk1 (26), through molecular marker-assisted selection and genetic engineering technologies.

Table 1.

Comparison of grain yield and other agronomic traits between 93-11 and NIL-qgl3

| Traits | 93-11 | NIL-qgl3 | P value |

| GL, mm | 10.21 ± 0.14 | 12.22 ± 0.23 | 1.21 × 10−15 |

| GW, mm | 2.62 ± 0.06 | 2.65 ± 0.07 | 0.015 |

| GT, mm | 2.18 ± 0.05 | 2.36 ± 0.04 | 0.034 |

| TGW, g | 30.08 ± 1.34 | 41.22 ± 1.42 | 3.10 × 10−19 |

| PL, cm | 24.50 ± 1.63 | 27.38 ± 2.32 | 1.38 × 10−08 |

| GPP | 216.60 ± 13.16 | 212.31 ± 17.64 | 0.71 |

| PH, cm | 113.60 ± 5.61 | 116.32 ± 4.34 | 0.37 |

| TN | 7.69 ± 1.54 | 7.87 ± 2.32 | 0.66 |

| DTH, d | 156.30 ± 3.50 | 158.50 ± 4.20 | 0.89 |

| YPP, kg | 12.84 ± 0.46 | 14.92 ± 0.38 | 8.63 × 10−12 |

All traits data are given as mean ± SD. Each P value for each trait was obtained from a t test between NIL-qgl3 and 93-11. DTH, days to heading (summer 2012, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China); GL, grain length; GPP, grains per panicle; GT, grain thickness; GW, grain width; PH, plant height; PL, panicle length; TGW, thousand filled-grain weight; TN, tiller number per plant; YPP, yield per plot.

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of the qgl3 effects on hybrid rice. (A) Comparison of grains and brown rice of three pairs of hybrids. (Scale bar: 10 mm.) (B) Actual grain yields of different hybrids in plots. (C) Chalk rates of white rice of different hybrids. P values from a t test were indicated.

Methods

Plant Materials.

The extra large-grain rice accession N411 (Oryza sativa L. japonica) was screened from more than 7,000 germplasms and used as a desirable allele donor parent. The small-grain indica rice variety N643 was crossed with N411 to create an F2 population for primary QTL analysis. A high-quality elite variety 93-11 (indica), was used as the recurrent parent to further validate and disassemble qGL3 by the backcrossing method. NIL for qgl3 (NIL-qgl3), which carries a ∼113-kb segment, including the N411 qgl3 allele (from XJ19 to RM15575) in 93-11 background, was developed by backcrossing and molecular marker analysis. A japonica cultivar, ZH11, was used in the genetic transformation. Three T-DNA insertion mutants for OsPPKLs 3D-50056.R, 3A-06810.L, and 2C-10162.L in the japonica Dongjin background were obtained from Kyung Hee University, Korea (http://cbi.khu.ac.kr/RISD_DB.html) (15, 16). Three photothermosensitive male sterile lines, P88S, Peiai64S, and Guangzhan63S, were crossed, respectively, with 93-11 and NIL-qgl3 to produce six combinations, P88S/93-11, PA64S/93-11, GZ63S/93-11, P88S/NIL-qgl3, PA64S/NIL-qgl3, and GZ63S/NIL-qgl3 for yield trials. The 94 rice varieties used in sequence analysis of qGL3 are listed in Table S4.

Primers.

Primers used for QTL mapping are listed in Table S3 and those for gene cloning, expression analysis and vectors construction are given in Table S6.

QTL Mapping of qGL3.

An F2 population of 182 plants, derived from a cross between N411 and N643, was used to construct a genetic map with 108 polymorphic SSR markers distributing averagely in the rice genome for primary QTL analysis. To fine-map the qGL3 locus, additional SSR markers in the target region were selected from the previously published SSRs (27), and eight InDel markers (Table S3) were developed in this study. The genetic map was constructed using MapMaker3.0/EXP version 3.0 (28). QTL analysis was performed by IciMapping3.1 (www.isbreeding.net/) along with the composite interval mapping method (29), and the threshold was obtained by 1,000 permutations. The distribution of grain length of 206 random BC2F3 plants confirmed that the qGL3 locus was disassembled to a single genetic factor for grain length (Fig. S1). The genotype of individuals could be determined by the phenotype of grain length (9.6–10.3 mm for the 93-11 homozygote, 10.6–11.5 mm for the heterozygote, and 11.8–12.8 mm for the N411 homozygote).

Gene Cloning, Construct Generation, and Transformation.

The full-length OsPPKL1N411 was amplified from cDNA samples of N411, and OsPPKL193-11, OsPPKL2, and OsPPKL3 were amplified from 93-11. These four full-length genes were cloned into the plant binary vector pCAMBIA1300S (30) to generate OE-OsPPKL1N411, OE-OsPPKL193-11, OE-OsPPKL293-11, and OE-OsPPKL393-11, respectively. The truncated OsPPLK193-11 constructs lacking either PP2A or Kelch domains were amplified from 93-11 and cloned into vector pCAMBIA1300S to generate constructs OE-Kelch93-11 or OE-PP2A93-11 (Fig. 2E). All of the genes or gene fragments were controlled by the CaMV 35S promoter and introduced into ZH11 by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation as reported previously (31).

Expression Analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from various plant tissues of 93-11 and NIL-qgl3 using a RNA extraction kit (RNAiso Plus; TaKaRa Bio, Inc.). The first-strand cDNA was synthesized using 6 μg RNA and 4 μg reverse-transcriptase mix (PrimeScript RT Master Mix Perfect Real Time; TaKaRa Bio, Inc.) in a volume of 40 μL. Semiquantitative PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 μL containing 2 μL of cDNA, 0.2 mM gene-specific primers, 2.5 μL 1× RT buffer, 10 μM dNTP mix. The rice OsRac1 gene was used as the internal control. Real-time PCR was carried out in a total volume of 25 μL containing 2 μL of cDNA, 0.2 mM gene-specific primers, 12.5 μL SYBR Premix Ex Taq II, and 0.5 μL of Rox Reference Dye II (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.), using an ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A rice 18S rRNA gene was used as the internal control. The relative quantification of the transcript levels was performed using the comparative Ct method (32).

Histological Observation.

The spikelets of 93-11 and NIL-qgl3 at three various developing stages (stage 1, 2 mm; stage 2, 5 mm; stage 3, maturity) were collected and treated with 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde, vacuumed three times, and fixed for 24 h as described previously (33). The outer surfaces of glumes of the spikelets were observed with a scanning electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, and cell density of the glume was calculated as cell number mm−1 in longitude.

Plant Growth Conditions.

To evaluate the effect of qgl3, the yields and other agronomic traits of 93-11 and NIL-qgl3 were compared by using three pairs (P88S/93-11 and P88S/NIL-qgl3; PA64S/93-11 and PA64S/NIL-qgl3; and GZ63S/93-11 and GZ63S/NIL-qgl3) of rice materials, which were grown in the Jiangpu Experiment Station of Nanjing Agricultural University. A total of 320 plants for each material were grown in a plot of 13.4 m2 with three replicates. For each plot, the grain yield and other agronomic traits, including days to heading, plant height, tiller number, panicle length, grain number, grain length, grain width, grain thickness, filled-grain weight, and chalk rate of white rice, were measured and analyzed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 31071386, National High Technology Research and Development Program of China Grant 2006AA10A102, National Science and Technology Support Plan of China Grant 2006BAD01A10-3, and Open Subject of State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology Grant 110101.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1219776110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zhang Q. Strategies for developing green super rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(42):16402–16409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708013104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan C, et al. GS3, a major QTL for grain length and weight and minor QTL for grain width and thickness in rice, encodes a putative transmembrane protein. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;112(6):1164–1171. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takano-Kai N, et al. Evolutionary history of GS3, a gene conferring grain length in rice. Genetics. 2009;182(4):1323–1334. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.103002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao H, et al. Linking differential domain functions of the GS3 protein to natural variation of grain size in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(45):19579–19584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014419107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang X, et al. Natural variation at the DEP1 locus enhances grain yield in rice. Nat Genet. 2009;41(4):494–497. doi: 10.1038/ng.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Y, et al. Deletion in a quantitative trait gene qPE9-1 associated with panicle erectness improves plant architecture during rice domestication. Genetics. 2009;183(1):315–324. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.102681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S, et al. The plant-specific G protein γ subunit AGG3 influences organ size and shape in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2012;194(3):690–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S, et al. Roles of the Arabidopsis G protein γ subunit AGG3 and its rice homologs GS3 and DEP1 in seed and organ size control. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7(10):1357–1359. doi: 10.4161/psb.21620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song XJ, Huang W, Shi M, Zhu MZ, Lin HX. A QTL for rice grain width and weight encodes a previously unknown RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):623–630. doi: 10.1038/ng2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shomura A, et al. Deletion in a gene associated with grain size increased yields during rice domestication. Nat Genet. 2008;40(8):1023–1028. doi: 10.1038/ng.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weng J, et al. Isolation and initial characterization of GW5, a major QTL associated with rice grain width and weight. Cell Res. 2008;18(12):1199–1209. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, et al. Natural variation in GS5 plays an important role in regulating grain size and yield in rice. Nat Genet. 2011;43(12):1266–1269. doi: 10.1038/ng.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang S, et al. Control of grain size, shape and quality by OsSPL16 in rice. Nat Genet. 2012;44(8):950–954. doi: 10.1038/ng.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakamoto T, Matsuoka M. Identifying and exploiting grain yield genes in rice. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008;11(2):209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeon JS, et al. T-DNA insertional mutagenesis for functional genomics in rice. Plant J. 2000;22(6):561–570. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeong DH, et al. Generation of a flanking sequence-tag database for activation-tagging lines in japonica rice. Plant J. 2006;45(1):123–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, Zhang D, Hannink M, Beamer LJ. Crystal structure of the Kelch domain of human Keap1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(52):54750–54758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li M, et al. Mutations in the F-box gene LARGER PANICLE improve the panicle architecture and enhance the grain yield in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011;9(9):1002–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Druet T, Georges M. A hidden Markov model combining linkage and linkage disequilibrium information for haplotype reconstruction and quantitative trait locus fine mapping. Genetics. 2010;184(3):789–798. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.108431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan S, et al. Seed size is determined by the combinations of the genes controlling different seed characteristics in rice. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123(7):1173–1181. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1657-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mora-García S, et al. Nuclear protein phosphatases with Kelch-repeat domains modulate the response to brassinosteroids in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2004;18(4):448–460. doi: 10.1101/gad.1174204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim TW, et al. Brassinosteroid signal transduction from cell-surface receptor kinases to nuclear transcription factors. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(10):1254–1260. doi: 10.1038/ncb1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiao Y, et al. Regulation of OsSPL14 by OsmiR156 defines ideal plant architecture in rice. Nat Genet. 2010;42(6):541–544. doi: 10.1038/ng.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miura K, et al. OsSPL14 promotes panicle branching and higher grain productivity in rice. Nat Genet. 2010;42(6):545–549. doi: 10.1038/ng.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su Y, et al. Map-based cloning proves qGC-6, a major QTL for gel consistency of japonica/indica cross, responds by Waxy in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123(5):859–867. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1632-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tian Z, et al. Allelic diversities in rice starch biosynthesis lead to a diverse array of rice eating and cooking qualities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(51):21760–21765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912396106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCouch SR, et al. Development and mapping of 2240 new SSR markers for rice (Oryza sativa L.) DNA Res. 2002;9(6):199–207. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.6.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lincoln S, Daly M, Lander ES. 1992. Constructing genetic maps with MAPMAKER/EXP 3.0. Whitehead Institute Technical Report (Whitehead Institute, Cambridge, MA)

- 29.Wang J. Inclusive composite interval mapping of quantitative trait genes. Acta Agron Sin. 2009;35(2):239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou X, et al. Involvement of a broccoli COQ5 methyltransferase in the production of volatile selenium compounds. Plant Physiol. 2009;151(2):528–540. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.142521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toki S, et al. Early infection of scutellum tissue with Agrobacterium allows high-speed transformation of rice. Plant J. 2006;47(6):969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Δ Δ C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ray TL, Payne CD. Scanning electron microscopy of epidermal adherence and cavitation in murine candidiasis: A role for Candida acid proteinase. Infect Immun. 1988;56(8):1942–1949. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1942-1949.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.