Abstract

Aging is characterized by a growing risk of disease and death, yet the underlying pathophysiology is poorly understood. Indeed, little is known about how the functional decline of individual organ systems relates to the integrative physiology of aging and probability of death of the organism. Here we show that intestinal barrier dysfunction is correlated with lifespan across a range of Drosophila genotypes and environmental conditions, including mitochondrial dysfunction and dietary restriction. Regardless of chronological age, intestinal barrier dysfunction predicts impending death in individual flies. Activation of inflammatory pathways has been linked to aging and age-related diseases in humans, and an age-related increase in immunity-related gene expression has been reported in Drosophila. We show that the age-related increase in expression of antimicrobial peptides is tightly linked to intestinal barrier dysfunction. Indeed, increased antimicrobial peptide expression during aging can be used to identify individual flies exhibiting intestinal barrier dysfunction. Similarly, intestinal barrier dysfunction is more accurate than chronological age in identifying individual flies with systemic metabolic defects previously linked to aging, including impaired insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling, as evidenced by a reduction in Akt activation and up-regulation of dFOXO target genes. Thus, the age-dependent loss of intestinal integrity is associated with altered metabolic and immune signaling and, critically, is a harbinger of death. Our findings suggest that intestinal barrier dysfunction may be an important factor in the pathophysiology of aging in other species as well, including humans.

Keywords: drosomycin, gut, longevity, SdhB

Aging involves the accumulation of damage to molecules, cells, and tissues, resulting in a decline in physiological functions and ultimately leading to an increased probability of death (1). Considerable progress has been made toward identifying genetic and environmental factors that modulate aging and lifespan, mainly as a result of pioneering work in invertebrate models, such as the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (2). Our understanding of the integrative pathophysiology of aging and age-onset mortality remains very limited, however (3). A number of markers of human aging and age-onset disease have been identified, including a chronic state of inflammation (4) and the development of insulin resistance (5). In a similar fashion, Drosophila aging is also associated with the increased expression of immunity-related genes (6, 7) and characteristics of insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling (IIS) impedance (8). The relationships between these different metabolic and inflammatory markers of aging and how they relate to age-related pathological changes remain unexplored, however. Moreover, although Drosophila is an important model for studying the genetics of aging, the ability to predict the age at which a fly will die based on a decline in organ function has proven elusive.

The intestinal epithelium forms a selective barrier that permits the absorption of nutrients, ions, and water and limits host contact with harmful entities, including microorganisms, dietary antigens, and environmental toxins. Structural and functional impairments within the intestinal epithelium have been reported in aged mammals (9) and Drosophila (10–13). Moreover, we (13) and others (14–16) have shown that the intestine represents an important target organ with respect to genetic interventions that promote longevity in both C. elegans and Drosophila (17). One interpretation of these findings is that maintaining intestinal integrity is an important determinant of health and viability at the organismal level; however, given that most assays of intestinal homeostasis are based on imaging techniques that require killing the flies (10–12), it has not been possible to determine how the onset of intestinal degeneration in individual flies relates to other aspects of aging and/or subsequent mortality.

We recently developed a noninvasive assay to determine intestinal integrity in individual flies (13). In the present work, we used this assay to further explore the role of intestinal barrier dysfunction in Drosophila aging. Our results show that loss of intestinal integrity accompanies aging across a range of Drosophila genotypes and environmental conditions. Interventions that extend lifespan, such as reduced temperature or dietary restriction, delay the onset of intestinal barrier defects, whereas loss of subunit b of mitochondrial complex II (sdhB) accelerates the onset of intestinal barrier defects and shortens the lifespan. Critically, intestinal barrier dysfunction is a better predictor of age-onset mortality than chronological age. Furthermore, we show that flies with intestinal barrier dysfunction display increased expression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), impaired IIS and reduced metabolic stores compared with age-matched animals without intestinal barrier defects. Thus, in a population of aging flies, we can now identify individuals showing systemic metabolic defects, markers of inflammation and impending death, based on a loss of organ function. These findings have broad implications for our understanding of the pathophysiology of aging.

Results

We recently reported that loss of intestinal barrier function in Drosophila can be detected by the presence of a nonabsorbable blue food dye (FD&C blue dye no. 1) outside of the digestive tract after feeding (13). We also showed that up-regulation of the Drosophila PGC-1 homolog improves intestinal integrity in aging flies and increases lifespan (13). To test the generality of these findings, we assayed a common laboratory strain, w1118, for age-dependent loss of intestinal integrity using the same approach. Both male and female flies showed a significant age-dependent increase in the number of flies exhibiting blue dye throughout the body after feeding (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1 A and B), hereinafter referred to as “Smurfs.” To determine whether additional nonabsorbable dyes could be used to detect intestinal barrier defects, we fed flies of different ages media containing either fluorescein or red food dye no. 40. As for blue dye no. 1 (Fig. S1C), in young animals both dyes were restricted to the digestive tract, whereas individual aged flies with either dye throughout the body were identified (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1D).

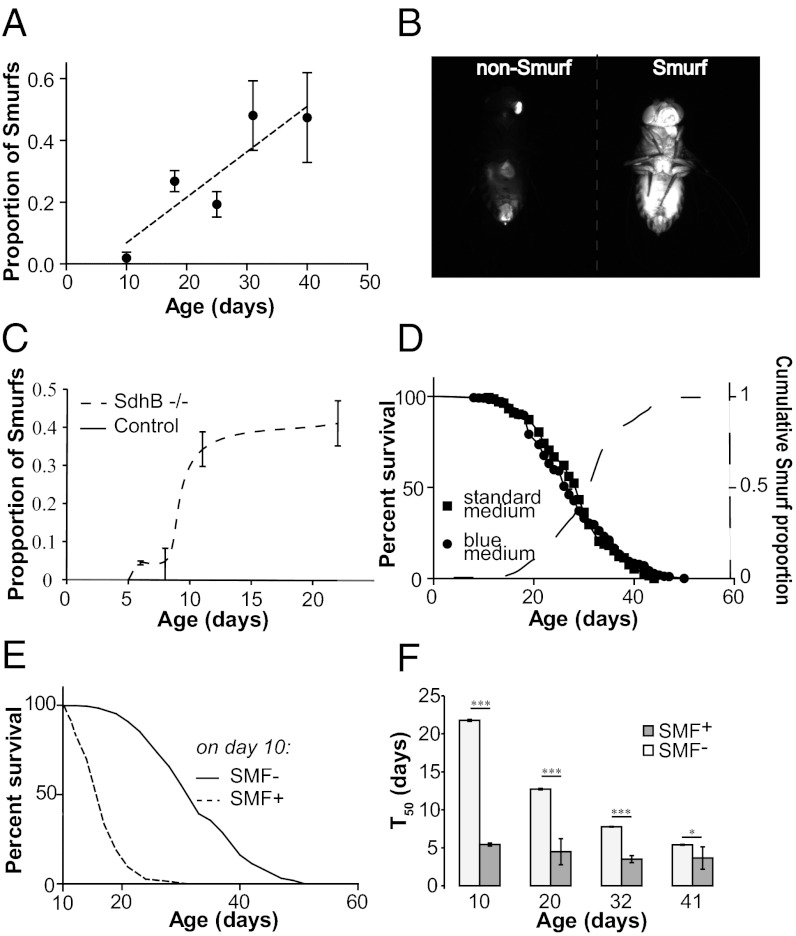

Fig. 1.

Intestinal barrier dysfunction predicts age-onset mortality and can be induced by mitochondrial dysfunction. (A) Proportion of flies showing loss of intestinal integrity in a w1118 female population as a function of age, assayed using blue dye no. 1. (B) Loss of intestinal integrity assayed with fluorescein in 30-d-old w1118 females. (Left) Dye is restricted to the proboscis and digestive tract. (Right) Fluorescein is seen throughout the body. (C) Proportion of flies showing loss of intestinal integrity in sdhB mutants compared with control flies carrying a transgenic genomic DNA rescue fragment. At 22 d, sdhB mutants show an increased proportion of Smurfs (P < 0.0001, binomial test). n = 4 replicates (vials) per time point. (D) Survival curves of w1118 maintained on standard medium (n = 151 female flies) or on the same medium containing blue dye no. 1 (n = 154 female flies). The dashed curve represents the cumulative proportion of dead Smurfs in the population. (E) Survival curves of 10-d-old non-Smurf (SMF−; n = 2,672) and Smurf (SMF+; n = 148) w1118 females. Smurf flies have a lower remaining lifespan than non-Smurfs (P < 0.0001, log-rank test). (F) T50 of Smurf and non-Smurf w1118 females separated at age 10, 20, 32, and 41 d. At day 10, n = 148 female Smurf flies and 2,672 female non-Smurf flies; at day 20, n = 571 female Smurf flies and 2,122 female non-Smurf flies; at day 32, n = 682 female Smurf flies and 1,016 female non-Smurf flies; at day 41, n = 229 female Smurf flies and 280 female non-Smurf flies. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.0001, by the Student t test on the average T50 value of independent vials. Error bars represent mean ± SEM.

Several lines of evidence suggest that mitochondrial dysfunction is an important factor in the increased risk of disease and death associated with aging (18, 19). In both Drosophila (20) and C. elegans (21), mutations in subunits of mitochondrial complex II result in elevated oxidative stress and reduced lifespan. To investigate the potential role of mitochondrial dysfunction in the age-related loss of intestinal integrity, we examined flies carrying a defect in sdhB, which displayed reduced longevity (Fig. S1E). Strikingly, after just 12 d, ∼35% of sdhB mutants showed intestinal barrier defects (Fig. 1C). At this age, there was no detectable loss of intestinal integrity in control flies. In addition, we found that exposure to hyperoxia (85% O2) can produce intestinal barrier defects in young flies (Fig. S1 F and G). Taken together, these results indicate that mitochondrial dysfunction and/or oxidative stress can accelerate the onset of intestinal barrier dysfunction.

To further examine the link between the Smurf phenotype and age-onset mortality, we aged w1118 flies on standard medium with or without the blue dye throughout adult life. Although the presence of the blue dye in the medium did not impact longevity, all flies in the population exhibited the Smurf phenotype before death (Fig. 1D). Thus, the loss of intestinal integrity is tightly linked to mortality in this population. We next aged a population of w1118 flies on standard medium and fed the flies food containing the blue dye for 9 h every 10 d. This allowed us to separate individual Smurf flies from the general population every 10 d. Survivorship did not differ between the population of flies that underwent this procedure every 10 d and control flies maintained on standard food (Fig. S1H). Using this approach, we discovered that at 10 d of age, Smurf flies had a T50 of only 5.5 d, compared with ∼21 d for age-matched non-Smurfs (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, at 20, 32, and 41 d of age, Smurf flies had a significantly shorter remaining lifespan than chronologically age-matched non-Smurfs (Fig. 1F). These findings indicate that the Smurf phenotype is a predictor of age-onset mortality.

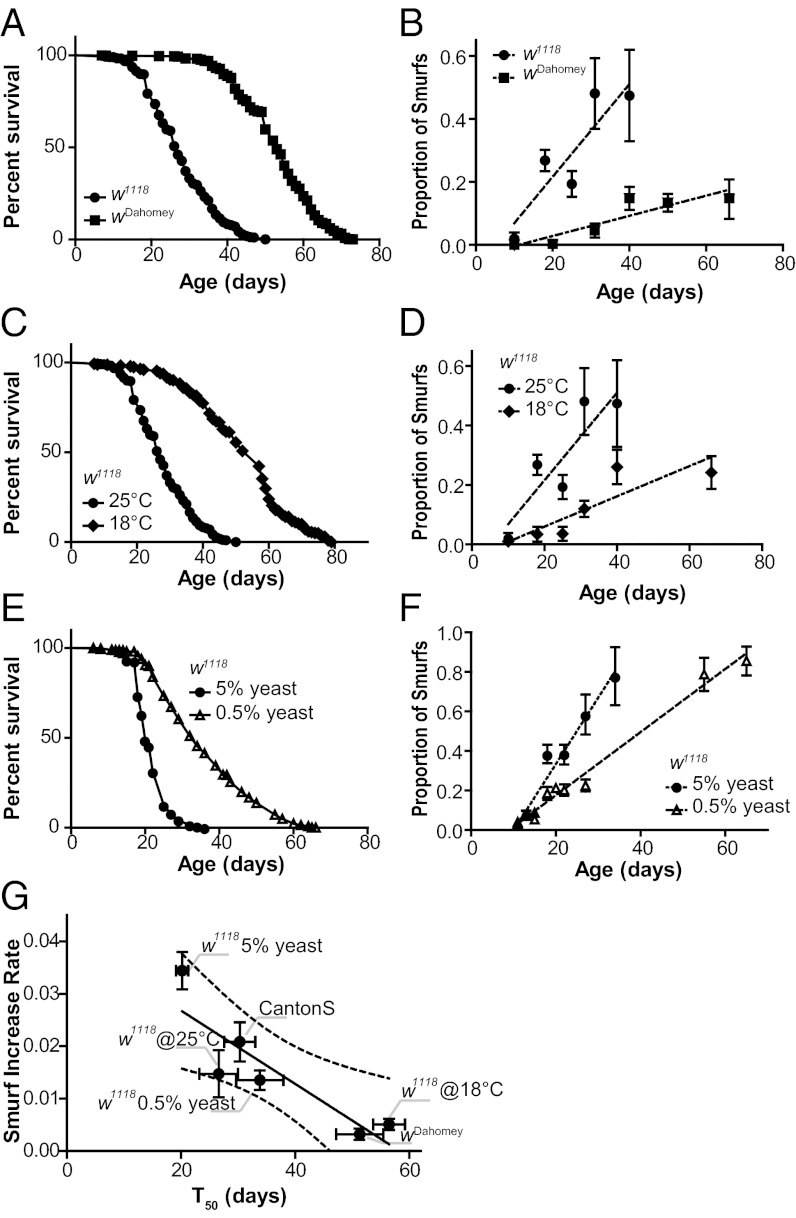

To further explore the relationship between the intestinal barrier dysfunction and lifespan, we examined the age-related increase in the Smurf phenotype in different strains and environmental conditions. To compare this rate of increase under different conditions, we approximated the trend of each dataset by the slope of the linear regression for the dataset, which we call the Smurf increase rate (SIR). We compared the SIR in three commonly used laboratory strains: wDahomey, Canton S, and w1118. Compared with w1118 flies, wDahomey flies had a significantly longer lifespan and a significantly lower SIR (Fig. 2 A and B). In contrast, Canton S and w1118 had similar lifespans and similar SIRs (Fig. S2 A and B). We next checked whether treatments known to increase lifespan in Drosophila, reduced temperature (18 °C vs. 25 °C) and yeast restriction (0.5% yeast extract vs. 5% yeast extract), affected the SIR. Both interventions produced a significantly increased lifespan (Fig. 2 C and E), associated with a decreased SIR (Fig. 2 D and F). Plotting the SIR against the T50 of the foregoing conditions demonstrated a significant negative correlation between the two parameters (Fig. 2G). Thus, intestinal barrier dysfunction occurs as a function of aging across different strains and environmental conditions.

Fig. 2.

Loss of intestinal integrity with aging in different strains and environmental conditions. (A) Survival curves of w1118 and wDahomey females. T50 was significantly lower in w1118 compared with wDahomey (27 d, n = 960 female flies vs. 53 d, n = 1,016 female flies; P < 0.0001, log-rank test). (B) The proportion of flies showing loss of intestinal integrity in w1118 and wDahomey females as a function of age, assayed using blue dye no. 1. The SIRw1118 is significantly higher than the SIRwDahomey (0.01472 ± 0.004513 vs. 0.003198 ± 0.0008473; PFtest < 0.001). Both regression lines show a significantly nonnull slope (PFtest < 0.01) and a significant correlation of the datasets (R2 > 0.79; PPearson < 0.05). n = 3–7 replicates (vials) per time point. (C) Survival curves of w1118 females maintained at 18 °C and 25 °C. T50 is significantly lower in w1118 maintained at 25 °C compared with those maintained at 18 °C (27 d, n = 960 female flies vs. 57 d, n = 613 female flies; P < 0.0001, log-rank test). (D) Proportion of flies showing loss of intestinal integrity in w1118 females maintained at 18 °C and 25 °C as a function of age, assayed using blue dye no. 1. The SIR25 °C is significantly higher than the SIR18 °C (0.01472 ± 0.004513 vs. 0.005086 ± 0.001068; PFtest < 0.05). Both regression lines show a significantly nonnull slope (PFtest < 0.05) and a significant correlation of the datasets (R2 > 0.75; PPearson < 0.05). n = 3–7 replicates (vials) per time point. (E) Survival curves of w1118 females maintained on 0.5% or 5% yeast extract. T50 is significantly lower in w1118 aged on a medium containing 5% yeast extract compared with those aged on a medium containing 0.5% yeast extract (20 d, n = 2,362 female flies vs. 34 d, n = 2,269 female flies; P < 0.0001, log-rank test). (F) Proportion of flies showing loss of intestinal integrity in w1118 females maintained on 0.5% or 5% yeast extract. The SIR5%ye is significantly higher than the SIR0.5%ye (0.03356 ± 0.003512 vs. 0.01597 ± 0.0007864; PFtest < 0.0001). Both regression lines show a significantly nonnull slope (PFtest < 0.0001) and a significant correlation of the datasets (R2 > 0.95; PPearson < 0.001). n = 8–10 replicates (vials) per time point. (G) Correlation between T50 and SIR of each of the tested populations above and those shown in Fig. S2. nvalues >18 for each SIR. The Pearson correlation test gives R2 = 0.7985, P < 0.05. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval; error bars represent mean ± SEM. All comparisons were also conducted using binomial regression (Fig. S2 C–F).

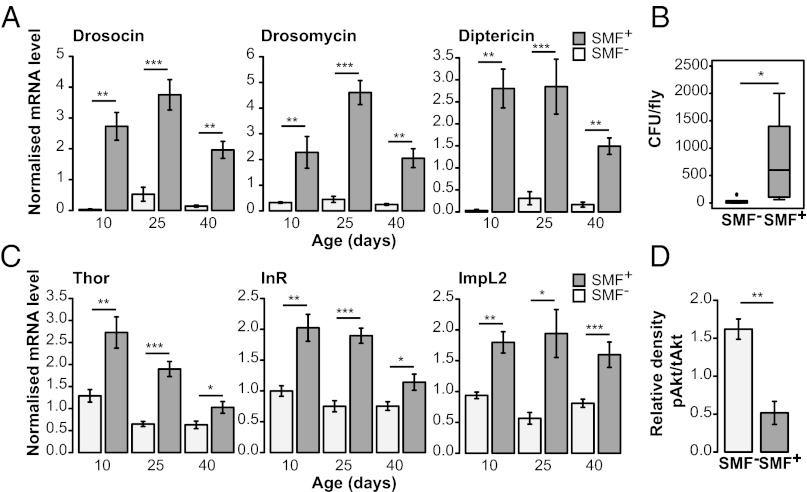

The differences in remaining lifespan among Smurfs of different chronological ages were greatly reduced compared with non-Smurfs (Fig. 1F). This could indicate that similar events occur in individuals before death regardless of chronological age. We hypothesized that in aged flies, intestinal barrier dysfunction may be associated with changes in immunity-related gene expression. Indeed, increased expression of AMPs has been reported in aged flies (6, 7), and AMP expression in young flies is negatively correlated with remaining lifespan (7). Thus, we examined the relationship between intestinal integrity and AMP expression in aging flies. To do so, we assayed expression levels of several AMP genes in age-matched Smurf and non-Smurf w1118 and Canton S flies. Smurf flies showed significant increases in AMP expression compared with age-matched non-Smurfs both in the gut and systemically, regardless of chronological age, diet, or genotype (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3 A–C). Although some aged non-Smurfs did show increased AMP expression compared with young animals, the magnitude of the expression changes were much lower than that seen in the Smurfs (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3 A–C). These data indicate that the reported increases in AMP expression in aged Drosophila populations (6, 7) may be largely related to the presence of an increased proportion of animals with intestinal barrier defects showing high levels of AMP expression. To better understand these findings, we assayed the internal bacterial load of age-matched Smurf and non-Smurf w1118 and Canton S flies. In both genotypes, Smurf flies showed significantly increased internal bacterial loads compared with age-matched flies without detectable intestinal barrier defects (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3D). These findings are consistent with a previous report of increased bacterial loads in aged flies (22) and indicate that loss of intestinal integrity in aged flies is associated with changes in the fly microbiome.

Fig. 3.

Loss of intestinal integrity, AMP expression, and IIS in aging flies. (A) Systemic expression of drosomycin (Drs), drosocin (Dro), and diptericin (Dpt) in 10-, 25-, and 40-d-old non-Smurf (SMF−) and Smurf (SMF+) w1118 flies. At 10 d, n = 3 female flies, 6 replicates; at 25 and 40 d, n = 3 female flies, 8 replicates. Increases in Dro and Dpt expression between 10 and 40 d in the SMF− population are also statistically significant (P values: Dro, <0.05; Dpt, <0.05). (B) Total number of bacterial colony-forming units (CFU) cultured from the interior of 25-d-old non-Smurf (SMF−) and Smurf (SMF+) w1118 flies. n = 3 female flies, 5 replicates. (C) Systemic expression of Thor, InR, and ImpL2 in 10-, 25-, and 40-d-old non-Smurf (SMF−) and Smurf (SMF+) w1118 flies. At 10 d, n = 3 female flies, 6 replicates; at 25 and 40 d, n = 3 female flies, 8 replicates. Expression levels of Thor and ImpL2 are significantly reduced in the SMF− population at 25 d (P values: Thor, <0.01; ImpL2, <0.01) relative to 10 d. Thor is also reduced at 40 d (P < 0.01). InR shows no significant difference in expression in the SMF− population. (D) Ratio of phosphorylated Akt level to total Akt level in 25-d-old non-Smurf (SMF−) and Smurf (SMF+) w1118 flies, calculated after normalization to total protein loaded per lane. n = 3 female flies, 3 replicates. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The metabolic syndrome, also known as the insulin resistance syndrome, is a clinical condition comprising physiological and biochemical abnormalities predisposing individuals to a host of age-onset diseases, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (5). A recent study using an acute food response paradigm reported that old flies display an insulin resistant-like phenotype (8); thus, we examined the relationship between intestinal barrier dysfunction and IIS activity in aging flies. We first assayed the expression levels of three Drosophila FOXO (dFOXO) target genes—Thor (4E-BP), Insulin-like receptor (InR), and ImpL2 —which are normally induced when IIS is repressed and dFOXO is activated (23–25). Smurf flies showed significantly higher transcript levels of all three genes compared with age-matched non-Smurfs (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3E), consistent with increased dFOXO activity and reduced IIS.

We next evaluated activation of the insulin effector kinase Akt by measuring levels of serine-505–phosphorylated Akt protein, and found significantly lower levels of activated Akt, an additional marker of impaired IIS, in Smurf flies compared with age-matched non-Smurfs (Fig. 3D and Fig. S3 F and G). Thus, as with AMP expression level, loss of intestinal integrity can be used to identify individual aged flies with impaired IIS relative to age-matched flies without detectable intestinal barrier defects.

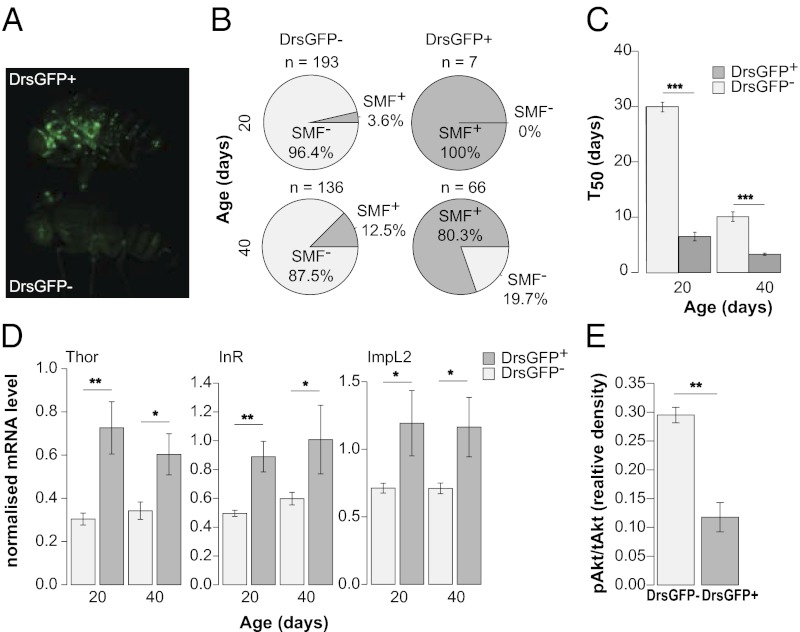

Given that the Smurf phenotype can be used to identify aged animals that display increased expression of AMPs, we tested whether the converse was true. To detect AMP expression in vivo, we aged flies carrying a drosomycin-GFP (Drs-GFP) reporter transgene (26) (Fig. 4A). As expected, the numbers of Drs-GFP+ animals increased significantly with age (Fig. S4A). We next separated Drs-GFP+ and Drs-GFP− individuals at different time points and assayed each population for Smurf animals. Selection for Drs-GFP+ expression greatly enriched the proportion of Smurfs in the population (Fig. 4B). Thus, the up-regulation of Drs expression during aging is highly correlated with a loss of intestinal integrity and can be used to enrich for animals exhibiting intestinal barrier dysfunction without the use of any food dye. Indeed, by feeding aged Drs-GFP+ flies medium containing fluorescein, we were able to observe the dye spreading from the intestine (Movie S1). Importantly, we confirmed a lower remaining lifespan in Drs-GFP+ flies compared with Drs-GFP− flies at two different time points (Fig. 4C). We note that the T50 is similar in Drs-GFP+ flies and conventionally identified Smurfs (Fig. 1F). Similar to conventionally identified Smurfs, aged Drs-GFP+ flies displayed increased expression of AMPs (Fig. S4B) and dFOXO target genes (Fig. 4D) compared with age-matched Drs-GFP− flies. In addition, aged Drs-GFP+ flies showed significantly lower levels of activated Akt compared with age-matched Drs-GFP− flies (Fig. 4E and Fig. S4 C and D). Thus, we conclude that loss of intestinal integrity is a harbinger of age-related mortality and is linked to impaired IIS, regardless of whether the intestinal barrier defects are detected directly using a food dye or indirectly via the up-regulation of Drs.

Fig. 4.

Increased Drs expression during aging is linked to intestinal barrier dysfunction, age-onset mortality, and impaired insulin signaling. (A) 30-d-old w;Drs-GFP flies, GFP+ (Upper) and GFP− (Lower). (B) Smurf proportions in w;Drs-GFP female populations segregated according to GFP expression level at age 20 d and 40 d. GFP+ populations show a significant enrichment of Smurfs compared with age-matched GFP− populations (20 d, P < 0.0001; 40 d, P < 0.0001; binomial tests). (C) T50 of w;Drs-GFP flies segregated according to GFP expression at age 20 d and 40 d. GFP+ flies have a lower remaining lifespan compared with GFP− flies (Student t test on the average T50 value of independent vials). At day 20, n = 96 Drs-GFP+ female flies and 223 Drs-GFP− female flies; at day 40, n = 164 Drs-GFP+ female flies and 223 Drs-GFP− female flies. (D) Systemic expression of Thor, InR, and ImpL2 in GFP− and GFP+ w;Drs-GFP females at age 20 d and 40 d. At age 20 d, n = 3 female flies, 6 replicates; at age 40 d, n = 3 female flies, 8 replicates. There is no significant change in the expression of these three genes in the GFP− population between 20 d and 40 d. (E) Ratio of phosphorylated Akt level to total Akt level in GFP− and GFP+ w;Drs-GFP females at age 40 d, calculated after normalization to total protein loaded per lane. n = 3 female flies, 3 replicates. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

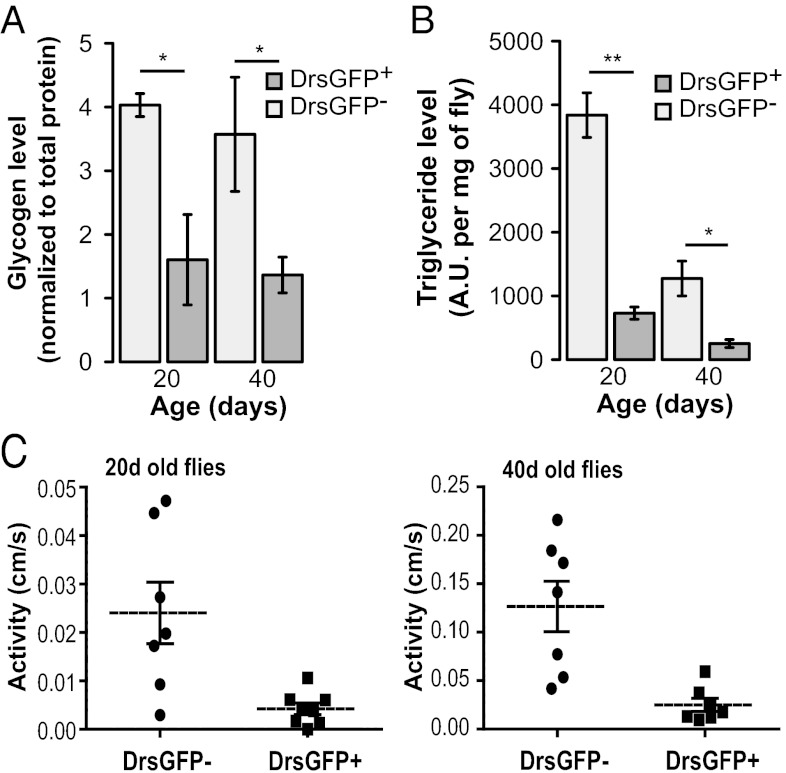

To further explore the relationship between aging-related AMP expression and metabolic homeostasis, we examined the levels of nutrient stores in age-matched Drs-GFP− and Drs-GFP+ flies. Remarkably, Drs-GFP+ flies exhibited significantly lower levels of stored glycogen (Fig. 5A) and triglycerides (Fig. 5B and Fig. S5A) compared with age-matched Drs-GFP− flies at two different time points. These findings are consistent with a previous report showing that at the population level, aged flies have reduced levels of both glycogen and triglycerides (16), and provides a means of identifying individual flies exhibiting these phenotypes based on increased AMP expression.

Fig. 5.

Reduced metabolic stores and spontaneous walking activity in aged flies showing Drs-GFP+ expression. (A) Glycogen content in GFP− and GFP+ w;Drs-GFP females at age 20 d and 40 d. n = 5 female flies, 3 replicates. (B) Triglyceride content in GFP− and GFP+ w;Drs-GFP females at age 20 d and 40 d. n = 5 female flies, 3 replicates. (C) Walking activity in GFP− and GFP+ w; Drs-GFP females at age 20 d (Left) and 40 d (Right). Spontaneous activity is significantly lower in Drs-GFP+ flies compared with Drs-GFP− flies (0.0043 ± 0.0011 cm/s at 20 d and 0.025 ± 0.007 cm/s at 40 d vs. 0.024 ± 0.006 cm/s at 20 d and 0.12 ± 0.03 cm/s at 40 d; n = 7 individual flies per time point and per condition; P < 0.01). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Finally, we sought to determine whether individual flies showing increased AMP expression during aging display alterations in spontaneous physical activity. We used video-assisted motion tracking to assay walking activity, speed, and distance in age-matched Drs-GFP+ and Drs-GFP− flies. As with other markers of aging, Drs-GFP+ flies displayed significantly less movement compared with age-matched Drs-GFP− flies at two different time points (Fig. 5C and Fig. S5B). Taken together, these results indicate that both reduced metabolic stores and decreased physical activity in individual flies are linked to the intestinal barrier dysfunction/increased AMP expression/impaired IIS (intestinal barrier dysfunction/AMP/IIS) axis of aging.

Discussion

A major challenge affecting our understanding of aging is to determine how the functional decline of different organ systems relates to the functioning and viability of the organism. In the present study, we used Drosophila as a model system to investigate the relationships among intestinal integrity, aging and death. We show that intestinal barrier dysfunction is linked to multiple markers of aging in Drosophila, including systemic metabolic dysfunction, increased expression of immunity-related genes, and reduced spontaneous physical activity. Furthermore, using two independent noninvasive approaches (Drs-GFP+ and a nonabsorbable food dye), we show that loss of intestinal integrity is tightly coupled to age-related mortality. Our findings suggest a means of identifying individual aged flies showing metabolic and inflammatory markers of aging based on the detection of intestinal barrier dysfunction. Interestingly, for certain markers of Drosophila aging (e.g., increased AMP expression), aged flies without detectable intestinal barrier defects show minimal changes compared with young flies. Thus, intestinal barrier dysfunction appears to be a better predictor of this marker of aging than chronological age.

Although our study supports the idea that intestinal homeostasis is an important determinant of fly lifespan, the proximal cause of death in aged flies remains to be determined. An important next step will be to examine the relationships between intestinal barrier dysfunction and the decline of other physiological systems in the fly. In addition, although we show that intestinal barrier dysfunction in aged flies is associated with increased AMP expression and impaired IIS, the cause-and-effect relationships remain unknown. Interestingly, activation of innate immune pathways has been implicated in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in mammals (27), and activation of the Toll pathway and the consequent induction of AMPs leads to reduced IIS in Drosophila (28). However, further work is needed to elucidate the temporal dynamics of the intestinal barrier dysfunction/AMP/IIS axis of aging. An interesting parallel to our findings is that a Drosophila model of infection-induced wasting showed metabolic changes overlapping with those linked to age-related mortality, impaired IIS, and reduced metabolic stores (29). Interestingly, intestines from aged flies contain higher counts of indigenous bacteria than their younger counterparts (22, 30), and this has been reported to influence epithelium renewal during aging (30). Thus, the role of the gut flora in the intestinal barrier dysfunction/AMP/IIS axis of aging is an interesting avenue for future exploration.

An additional set of questions concern the relevance of our findings to mammalian aging. Although the relationship between intestinal homeostasis and mammalian lifespan is less well understood, several age-related changes in the intestinal epithelium of rodents have been reported (9), including intestinal barrier dysfunction (31). The importance of the gut epithelium in human health is demonstrated by the growing number of disorders that have been linked to defects in intestinal barrier function, including intestinal or extraintestinal inflammatory disorders (32, 33), multiple sclerosis (34), chronic heart failure (35), cancer (36, 37), and Parkinson’s disease (38). In terms of mortality in humans, intestinal barrier dysfunction is reportedly common in critically ill patients and linked to development of the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (39–41). Moreover, a chronic state of inflammation (4) and the development of insulin resistance (5) are underlying factors in a wide range of aging-related human diseases. In light of our findings in Drosophila, it will be interesting to investigate the relationships among age-dependent changes in intestinal barrier function, inflammation, insulin resistance, and associated diseases of aging in mammals. Genetic interventions that enhance longevity are conserved from invertebrates to mammals (2); thus, it is possible that the pathophysiological underpinnings of aging are also conserved across great evolutionary distances.

Materials and Methods

Fly Stocks.

The standard laboratory strains w1118, Canton S, and wDahomey were used for detection of intestinal barrier defects during aging. w;Drs-GFP was used to examine Drs expression during aging. sdhB mutants and the genomic rescue control were described previously (20) and used to examine the impact of mitochondrial dysfunction on intestinal barrier function.

Smurf Assay.

Unless stated otherwise, flies were aged on standard medium until the day of the Smurf assay. Dyed medium was prepared using standard medium with dyes added at a concentration of 2.5% (wt/vol). Blue dye no. 1 and red dye no. 40 were purchased from SPS Alfachem, and fluorescein was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Flies were maintained on dyed medium for 9 h. A fly was counted as a Smurf when dye coloration could be observed outside of the digestive tract. To calculate the SIR, we plotted the average proportion of Smurfs per vial as a function of chronological age and defined the SIR as the slope of the calculated regression line. When the Smurf assay was performed on w;Drs-GFP animals, GFP expression level was scored before exposure to blue dye no. 1.

Identification of FluorSmurfs and Drs-GFP+ Flies.

Animals were sorted on ice and imaged using a Zeiss discovery v12 stereomicroscope. The Drs-GFP expression assay was conducted in a binary fashion. Animals were considered GFP+ when they showed GFP expression outside of the female sperm storage organ, previously described as a site of constitutive expression in these flies (26).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Reem Mehdoui for help with Drs-GFP fly work, Matthew Ulgherait for help with the initial characterization of Smurf flies, the Frye and Simmons laboratories for the use of their equipment, Matt Piper (University College London) for wDahomey flies, Marc Dionne (King’s College London) for Drs-GFP flies and helpful comments, and the University of California, Los Angeles Institute for Digital Research and Education Statistical Consulting Group for advice on statistical analysis. This work is supported by the National Institute on Aging (Grants R01 AG037514 and R01 AG040288) and the Ellison Medical Foundation. D.W.W. is an Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholar in Aging.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.S.S. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1215849110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kirkwood TB. Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell. 2005;120(4):437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenyon CJ. The genetics of ageing. Nature. 2010;464(7288):504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy MP, Partridge L. Toward a control theory analysis of aging. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:777–798. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.070606.101605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung HY, et al. Molecular inflammation: Underpinnings of aging and age-related diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 2009;8(1):18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lusis AJ, Attie AD, Reue K. Metabolic syndrome: From epidemiology to systems biology. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(11):819–830. doi: 10.1038/nrg2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pletcher SD, et al. Genome-wide transcript profiles in aging and calorically restricted Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Biol. 2002;12(9):712–723. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landis GN, et al. Similar gene expression patterns characterize aging and oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(20):7663–7668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307605101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris SN, et al. Development of diet-induced insulin resistance in adult Drosophila melanogaster. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822(8):1230–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkwood TB. Intrinsic ageing of gut epithelial stem cells. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125(12):911–915. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biteau B, Hochmuth CE, Jasper H. JNK activity in somatic stem cells causes loss of tissue homeostasis in the aging Drosophila gut. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(4):442–455. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi NH, Kim JG, Yang DJ, Kim YS, Yoo MA. Age-related changes in Drosophila midgut are associated with PVF2, a PDGF/VEGF-like growth factor. Aging Cell. 2008;7(3):318–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JS, Kim YS, Yoo MA. The role of p38b MAPK in age-related modulation of intestinal stem cell proliferation and differentiation in Drosophila. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1(7):637–651. doi: 10.18632/aging.100054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rera M, et al. Modulation of longevity and tissue homeostasis by the Drosophila PGC-1 homolog. Cell Metab. 2011;14(5):623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Libina N, Berman JR, Kenyon C. Tissue-specific activities of C. elegans DAF-16 in the regulation of lifespan. Cell. 2003;115(4):489–502. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durieux J, Wolff S, Dillin A. The cell–non-autonomous nature of electron transport chain-mediated longevity. Cell. 2011;144(1):79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biteau B, et al. Lifespan extension by preserving proliferative homeostasis in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(10):e1001159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rera M, Azizi MJ, Walker DW. Organ-specific mediation of lifespan extension: More than a gut feeling? Ageing Res Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: A dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green DR, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Mitochondria and the autophagy-inflammation-cell death axis in organismal aging. Science. 2011;333(6046):1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.1201940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker DW, et al. Hypersensitivity to oxygen and shortened lifespan in a Drosophila mitochondrial complex II mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(44):16382–16387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607918103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishii N, et al. A mutation in succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b causes oxidative stress and ageing in nematodes. Nature. 1998;394(6694):694–697. doi: 10.1038/29331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren C, Webster P, Finkel SE, Tower J. Increased internal and external bacterial load during Drosophila aging without life-span trade-off. Cell Metab. 2007;6(2):144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puig O, Marr MT, Ruhf ML, Tjian R. Control of cell number by Drosophila FOXO: Downstream and feedback regulation of the insulin receptor pathway. Genes Dev. 2003;17(16):2006–2020. doi: 10.1101/gad.1098703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang MC, Bohmann D, Jasper H. JNK extends life span and limits growth by antagonizing cellular and organism-wide responses to insulin signaling. Cell. 2005;121(1):115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teleman AA. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic regulation by insulin in Drosophila. Biochem J. 2010;425(1):13–26. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrandon D, et al. A drosomycin-GFP reporter transgene reveals a local immune response in Drosophila that is not dependent on the Toll pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17(5):1217–1227. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samuel VT, Shulman GI. Mechanisms for insulin resistance: Common threads and missing links. Cell. 2012;148(5):852–871. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiAngelo JR, Bland ML, Bambina S, Cherry S, Birnbaum MJ. The immune response attenuates growth and nutrient storage in Drosophila by reducing insulin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(49):20853–20858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906749106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dionne MS, Pham LN, Shirasu-Hiza M, Schneider DS. Akt and FOXO dysregulation contribute to infection-induced wasting in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2006;16(20):1977–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchon N, Broderick NA, Chakrabarti S, Lemaitre B. Invasive and indigenous microbiota impact intestinal stem cell activity through multiple pathways in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2009;23(19):2333–2344. doi: 10.1101/gad.1827009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz D, Hollander D, Said HM, Dadufalza V. Aging-associated increase in intestinal permeability to polyethylene glycol 900. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32(3):285–288. doi: 10.1007/BF01297055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farhadi A, Banan A, Fields J, Keshavarzian A. Intestinal barrier: An interface between health and disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18(5):479–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fasano A, Shea-Donohue T. Mechanisms of disease: The role of intestinal barrier function in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2(9):416–422. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yacyshyn B, Meddings J, Sadowski D, Bowen-Yacyshyn MB. Multiple sclerosis patients have peripheral blood CD45RO+ B cells and increased intestinal permeability. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41(12):2493–2498. doi: 10.1007/BF02100148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandek A, Rauchhaus M, Anker SD, von Haehling S. The emerging role of the gut in chronic heart failure. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11(5):632–639. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32830a4c6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin JE, et al. GUCY2C opposes systemic genotoxic tumorigenesis by regulating AKT-dependent intestinal barrier integrity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ullman TA, Itzkowitz SH. Intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(6):1807–1816. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forsyth CB, et al. Increased intestinal permeability correlates with sigmoid mucosa alpha-synuclein staining and endotoxin exposure markers in early Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12):e28032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris CE, et al. Intestinal permeability in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 1992;18(1):38–41. doi: 10.1007/BF01706424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doig CJ, et al. Increased intestinal permeability is associated with the development of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in critically ill ICU patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(2):444–451. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.2.9710092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fink MP, Delude RL. Epithelial barrier dysfunction: A1 unifying theme to explain the pathogenesis of multiple organ dysfunction at the cellular level. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21(2):177–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.