Abstract

Early secretory and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized proteins that are terminally misfolded or misassembled are degraded by a ubiquitin- and proteasome-mediated process known as ER-associated degradation (ERAD). Protozoan pathogens, including the causative agents of malaria, toxoplasmosis, trypanosomiasis, and leishmaniasis, contain a minimal ERAD network relative to higher eukaryotic cells, and, because of this, we observe that the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum is highly sensitive to the inhibition of components of this protein quality control system. Inhibitors that specifically target a putative protease component of ERAD, signal peptide peptidase (SPP), have high selectivity and potency for P. falciparum. By using a variety of methodologies, we validate that SPP inhibitors target P. falciparum SPP in parasites, disrupt the protein’s ability to facilitate degradation of unstable proteins, and inhibit its proteolytic activity. These compounds also show low nanomolar activity against liver-stage malaria parasites and are also equipotent against a panel of pathogenic protozoan parasites. Collectively, these data suggest ER quality control as a vulnerability of protozoan parasites, and that SPP inhibition may represent a suitable transmission blocking antimalarial strategy and potential pan-protozoan drug target.

Keywords: intramembrane proteolysis, small molecule, target validation

Protozoan pathogens, including the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, constitute one of the most substantial global public health problems faced today. The emergence and spread of drug-resistant parasites has rendered many of the traditional chemotherapeutics clinically ineffective in many cases (1). Therefore, the identification and validation of novel Plasmodium molecular targets would greatly facilitate the discovery of new antimalarial drugs.

In the pathogenic stage, P. falciparum resides within an erythrocyte, which is elaborately remodeled by the parasite to allow the infected cell to escape immune detection and to facilitate nutrient uptake and waste disposal in a cell with normally low metabolic activity. A necessary component of the parasite’s capacity to inhabit the erythrocyte is the establishment of a unique parasite-derived protein secretory network that allows protein trafficking to destinations beyond the parasite, including a parasitophorous vacuole and erythrocyte cytosol and plasma membrane (2).

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the hub of the secretory pathway, where secretory proteins are folded and targeted for their respective destination. The ER is sensitive to changes in calcium flux, temperature, and exposure to reducing agents, and, in higher eukaryotes, these stressors elicit transcriptional and translational responses to stabilize already synthesized secretory proteins and decrease the load of translocation into the ER, a network collectively called the unfolded protein response (UPR). In addition to the UPR, there exists a coordinated and extensive monitoring system in the ER to ensure that terminally misfolded proteins or peptides are quickly extracted from this compartment and then degraded via the ubiquitin–proteasome system in the cytosol in a process known as ER-associated degradation (ERAD) (3). Studies in yeast and mammalian cells have shown ERAD to be a complex network that comprises compartmentally restricted and partially redundant protein complexes. During periods of ER stress, ERAD and UPR work together to achieve protein homeostasis within the ER (4–7).

P. falciparum lacks conventional transcriptional regulation and shows little coordinated response to internal or external perturbations such as heat stress or drug toxicity (8). Intriguingly, the transcription factors that initiate the UPR (IRE1, ATF6) in mammalian cells are absent from the genome of P. falciparum (9–11). Lacking any transcriptional response, the down-regulation of translation, identification, and subsequent disposal of misfolded proteins would be the parasite’s major compensatory mechanisms to maintain ER homeostasis during periods of ER stress.

Here we show through a bioinformatics analysis that the ERAD pathway of protozoan pathogens, including P. falciparum, is highly simplified relative to mammalian cells, and that P. falciparum is therefore vulnerable to small molecules that have been established to inhibit proteins within the ERAD system. In particular, malaria parasites within multiple life stages, along with other protozoan pathogens, are highly sensitive to the inhibition of one of these putative ERAD proteins, signal peptide peptidase (SPP), which we validate to act in this ERAD pathway through a variety of techniques, and further suggest that SPP inhibition may be a viable antiparasitic strategy.

Results

A Bioinformatics Approach Identifies Minimal ERAD Pathway in Protozoan Pathogens, of Which P. falciparum Shows Heightened Susceptibility to Inhibition.

A recent analysis of the UPR machinery in protozoan parasites revealed a distinct UPR characterized by the absence of transcriptional regulation and therefore entirely reliant on translational attenuation in response to ER stress (12). As a result of this, Leishmania donovani parasites have heightened sensitization to compounds that promote ER stress, such as DTT (reducing agent) (12). In yeast and mammalian cells, ER stress initiates UPR and ERAD in an intimately coordinated fashion, whereby the induction of one process increases the capacity of the other (5, 7). Thus, we reasoned that the modified response to ER stress in protozoan pathogens also likely extends to the ERAD pathway.

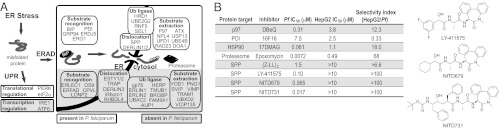

Our investigation of this hypothesis using standard orthologue detection tools revealed a striking lack of putative ERAD proteins in P. falciparum relative to the extensive mammalian network (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). All functional modules of the ERAD pathway (as named in ref. 7), including protein recognition, translocation, ubiquitin ligation, and protein extraction, showed far fewer orthologues in P. falciparum relative to the corresponding mammalian pathway. We expanded our inquiry to three other pathogenic protozoans, Toxoplasma gondii, Leishmania infantum, and Trypanosoma cruzi, to assess whether the reduction of the ERAD proteome is a common feature among protozoa (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). On average, each protozoan investigated showed a ∼50% to 60% decrease in orthologues shared with the mammalian ERAD system. As each of the genomes remains incompletely annotated, it may also be possible that some components from each organism are so divergent that they may have not been detected by our analysis. On the whole, the reduction in protozoan ERAD proteins suggests that the pathway as found in the parasites may be less dynamic than its mammalian counterpart, and that the loss of function of individual components of the protozoan pathway would severely compromise parasite viability.

Fig. 1.

P. falciparum has a minimal ERAD pathway and shows heightened susceptibility to inhibition of constituent proteins. (A) A bioinformatics analysis of ERAD in P. falciparum reveals a reduced number of ERAD orthologues in each functional module. Components of ERAD not identified in P. falciparum are sectioned in the shaded boxes, and proteins in white boxes have orthologues identified in P. falciparum. (B) Treatment of P. falciparum and human HepG2 cells with inhibitors of ERAD proteins reveals increased sensitivity of parasites vs. host cells. This is quantified by the selectivity index, which is a ratio of the IC50 for HepG2 cells divided by the IC50 for P. falciparum.

As a result of the inherent genetic intractability of P. falciparum, we undertook a small molecule-based approach to initially perform a small screen of well characterized inhibitors that target an array of ERAD pathway proteins. We focused on ERAD components identified in P. falciparum with known associated inhibitors, including heat shock protein 90 (13–15), protein disulfide isomerase (16), cytosolic AAA (ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities) ATPase p97 (or Cdc48; valosin-containing protein) (17, 18), ER intramembrane aspartyl protease SPP (19), and the proteasome. P. falciparum parasites were indeed susceptible to each of the inhibitors to varying degrees, and all compounds displayed IC50 values of less than 10 μM (Fig. 1B). In addition, each inhibitor was assayed against the human hepatocyte HepG2 cell line, and a selectivity index was produced to determine the fold increase in potency for the inhibitor toward P. falciparum vs. the human cell line. As predicted, the majority of compounds were more potent for P. falciparum vs. the human cell line (Fig. 1B). These data suggest that P. falciparum may be acutely susceptible to inhibition of the ERAD pathway, or to compounds that disrupt the homeostatic balance of the ER.

As P. falciparum was highly sensitive to the SPP inhibitor LY-411575, and this inhibitor showed no observable toxicity to host cells, we decided to focus on further chemical validation of P. falciparum SPP (PfSPP) as an antimalarial target. In addition, PfSPP is most similar to mammalian hSPP1, which is an aspartyl protease (∼40 kDa) in the same family as presenilin (PS). Because of the central role of PS in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease, a large number of inhibitors have been developed against this intramembrane aspartyl protease, and many of these inhibitors show cross-inhibition of SPP, including LY-411575. Therefore, we were able to “piggyback” on these efforts to screen a series of PS inhibitors based on the scaffold of LY-411575 in parasite replication assays. We show the top two hits, NITD731 and NITD697, which are potent against P. falciparum, with IC50 values of 17 nM and 65 nM, respectively (Fig. 1B), and not active at all against HepG2 cells, indicating a high degree of selectivity for malaria parasites over mammalian cells.

PfSPP Is a Component of ERAD and Its Role Can Be Inhibited by Small Molecules.

Recent studies in mammalian cells have established the necessity of hSPP1 during the process of dislocation during virus-mediated ERAD of MHC class I molecules (20–23). In addition, hSPP1 associates with a number of proteins required for ERAD, including ubiquitin ligase TCR8 and protein disulfide isomerase, and also assembles with misfolded membrane proteins (21, 22, 24, 25).

Recent studies have concluded that human hSPP1 and PfSPP are ER-resident proteins (26–28). We corroborated these findings by localizing PfSPP in parasites to the ER by indirect immunofluorescence by using a PfSPP antibody (Fig. S2). Throughout the parasite life cycle, we observed strict perinuclear localization of PfSPP in the ER, in accordance with what has been previously observed. Co-indirect immunofluorescence assays performed with an antibody to the resident ER protease plasmepsin V or the generation of a parasite line expressing HA-tagged PfSPP also confirmed ER residency, in agreement with previously published literature (26–28) (Fig. S2).

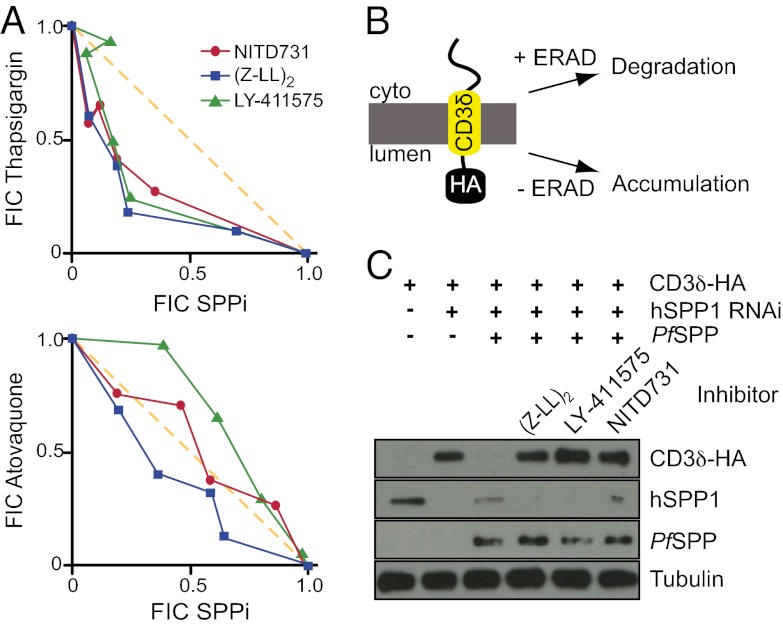

To assess the effect SPP inhibitors have on the ability of parasites to cope with ER stress, we treated P. falciparum parasites simultaneously with thapsigargin and SPP inhibitors and analyzed the effects of the inhibitor combinations for evidence of synergy. Thapsigargin causes the release of calcium from the ER, compromising the ER’s ability to produce properly folded proteins, and is lethal to parasites (Fig. S3) (29). The combination treatment of thapsigargin with the SPP inhibitors (Z-LL)2, LY-411575, or NITD731 produced synergistic parasiticidal effects beyond what would be expected by simply adding the effects of the individual compounds together (Fig. 2A). The results are presented as an isobologram of the varying ratios of the two compounds, in which points below the line of additivity indicate synergy. As a negative control, no synergy was seen with atovaquone (Fig. 2A, Lower), an antimalarial ubiquinone analogue whose mechanism of action involves the mitochondria (30). This suggests that the synergy between SPP inhibitors and thapsigargin is caused by the ER stress (thapsigargin) and the parasite’s compromised ability to manage it (PfSPP inhibition), which further connects PfSPP to a potential function within the parasite’s ERAD network.

Fig. 2.

SPP inhibitors sensitize parasites to ER stress and PfSPP facilitates the degradation of a canonical ERAD substrate. (A) Individual IC50 values against parasites were determined for each SPP inhibitor and thapsigargin, and for each inhibitor in combination with thapsigargin, at four different fixed ratios. The fractional IC50 value (FIC; IC50 of inhibitor in combination divided by IC50 of inhibitor alone) was determined for each inhibitor in each combination and plotted on the isobologram. The x axis indicates the FIC of the SPP inhibitors. The average ΣFIC for the SPP inhibitors with thapsigargin were 0.80, 0.72, and 0.79 for NITD731, LY-411575, and (Z-LL)2, respectively. The diagonal line represents a ΣFIC of 1, indicating additivity between the two inhibitors. Area below the line (i.e., ΣFIC of <1) indicates a synergistic combination. (B) Schematic of the CD3δ-HA ERAD assay. CD3δ-HA is degraded in the presence of a functional ERAD network and stabilized in its absence or inhibition. (C) U-2 OS cells actively degrade CD3δ-HA via ERAD, a process that can be abolished by the knockdown of hSPP1. This process can be rescued by the coexpression of PfSPP. SPP inhibitors block the PfSPP-mediated degradation of the substrate.

To provide a more direct link between PfSPP and its role in ERAD, we used an established ERAD assay, which makes use of an intrinsically unstable protein, CD3δ, that has been used previously to identify novel ERAD components and small molecules that inhibit the disposal of unstable proteins (31, 32). In this system, CD3δ is naturally degraded via ERAD when expressed in most cell lines. When ERAD is impaired, the CD3δ protein accumulates, which can be monitored by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2B).

Initially, we attempted to use this system by expressing CD3δ in P. falciparum or T. gondii but were unable to derive parasites that could express CD3δ, which may indicate how sensitive these parasites are to unfolded proteins in the ER. Therefore, we switched to a human cell line-based assay wherein CD3δ tagged with an HA epitope was transfected and assayed by Western blot. Upon treatment of transfected cells with the translation inhibitor cycloheximide, levels of CD3δ-HA decreased (Fig. 2C, lane 1). siRNA knockdown of hSPP1 abrogated degradation of CD3δ-HA, which produced a concomitant accumulation of CD3δ-HA protein (Fig. 2C, lane 2). This corroborates previous literature that showed that hSPP1 mediates ERAD of CD3δ (22). The loss of ERAD-mediated degradation of CD3δ-HA in cells in which hSPP1 was knocked down was rescued with the expression of a codon-optimized PfSPP (Fig. 2C, lane 3). In addition to the aforementioned genetic studies, treatment of the CD3δ-HA–expressing cells complemented with PfSPP with SPP inhibitors also resulted in the inability of the cells to degrade CD3δ-HA (Fig. 2C, lanes 4–6), confirming that these inhibitors impaired PfSPP function in ERAD. This suggests that PfSPP performs a similar role as its mammalian counterpart, and that inhibition of PfSPP likely restricts its ERAD function in P. falciparum.

SPP Inhibitors Directly Block PfSPP Activity in Heterologous Proteolytic Assay.

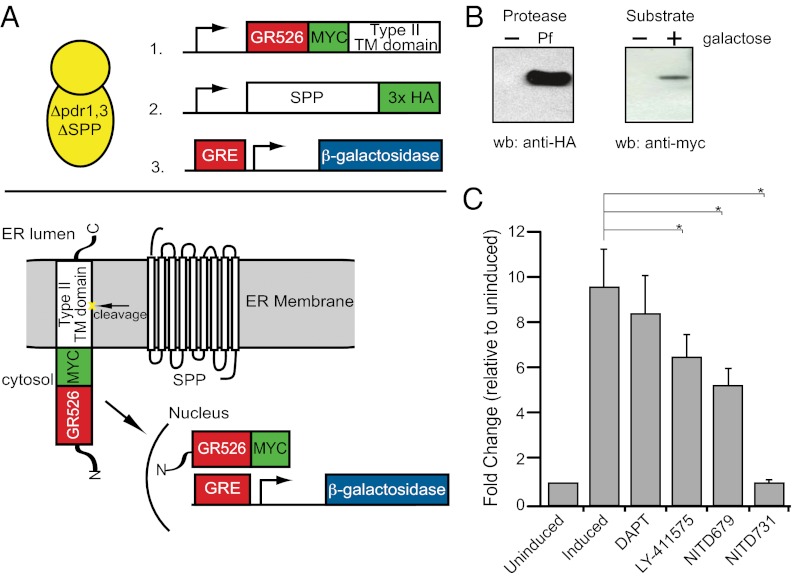

We next endeavored to assess whether our SPP inhibitors blocked the proteolytic activity of PfSPP. Therefore, we developed a cell-based SPP protease assay to interrogate its activity (Fig. 3A). Initially, we envisioned that we would build this assay in P. falciparum; however, genetic tractability was severely limiting, and PfSPP is an essential gene, so perturbations to this protein are lethal to the organism (33). To circumvent this difficulty, we designed the assay in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae because of the genetic manipulability of this system and because S. cerevisiae contains no PS orthologue (thus yielding lower potential background signal) and only a single SPP gene (rather than five as in mammalian cells). It is worth noting that previous reports indicated that there was no SPP in yeast; however, an SPP-like protein [YKL100c; i.e., S. cerevisiae SPP (ScSPP)] is encoded in the yeast genome that is homologous to human hSPP1 (Fig. S4). An ScSPP KO strain was made in the ∆pdr1,3 strain (a double-KO strain that lacks multidrug resistance pumps). The ∆spp yeast KO was viable and had no gross phenotypic differences compared with the WT strain. The ∆pdr1,3-∆spp strain was then transformed with the following plasmids: (i) a reporter consisting of glucocorticoid response element (GRE) fused to LacZ; (ii) a galactose-inducible expression plasmid with a truncated glucocorticoid receptor-fused C-terminal to the transmembrane domain of human CMV glycoprotein UL-40 (gpUL40), a canonical Type II transmembrane SPP substrate; and (iii) PfSPP codon-optimized for eukaryotic expression. Upon cleavage of the transmembrane domain by PfSPP (Fig. 3A, Lower), the glucocorticoid receptor is no longer anchored by the transmembrane domain of the substrate and translocates into the nucleus, where it binds the GRE that drives expression of β-gal. PfSPP activity is then determined by β-gal activity via the addition of a chemiluminescent substrate of β-gal.

Fig. 3.

PfSPP is an active protease inhibited by PS/SPP inhibitors. (A) In the yeast activity assay, SPP cleaves the substrate and releases GR526, which translocates to the nucleus and binds the GRE. Expression of lacZ is detected via a luminescent substrate. (B) Expression of HA-tagged PfSPP in the ∆pdr1,3-∆SPP yeast strain as detected by Western blotting for HA. gpUL40 is detected only upon induction of galactose, as detected by anti-myc Western blotting. (C) ∆pdr1,3 ∆SPP with an overexpressed PfSPP shows successful cleavage of the substrate, inhibition by 50 µM LY-411575, NITD679, and NITD731, but no change with the PS-specific inhibitor DAPT at 50 µM. The fold activity is a ratio of induced, induced plus 50 µM LY-411575, or induced plus 50 µM DAPT to uninduced. Mean IC50 ± SD is shown (*P < 0.05).

To test the activity of PfSPP, we used the engineered yeast ∆pdr1,3-∆spp strain containing the reporter and substrate plasmids and overexpressed PfSPP. The expression of PfSPP and substrate were detected by using a Western blot with anti-myc and anti-HA tag antibody, respectively (Fig. 3B). The results in Fig. 3C show that PfSPP is indeed an active protease that cleaves the GR526–gpUL40 substrate. We next confirmed that the SPP inhibitors LY-411575, NITD679, and NITD731 inhibited PfSPP activity. In contrast, the PS-specific inhibitor DAPT showed no inhibition of PfSPP (Fig. 3C and Fig. S5), illustrating that proteolytic activity of PfSPP is specifically inhibited by these small-molecule SPP inhibitors.

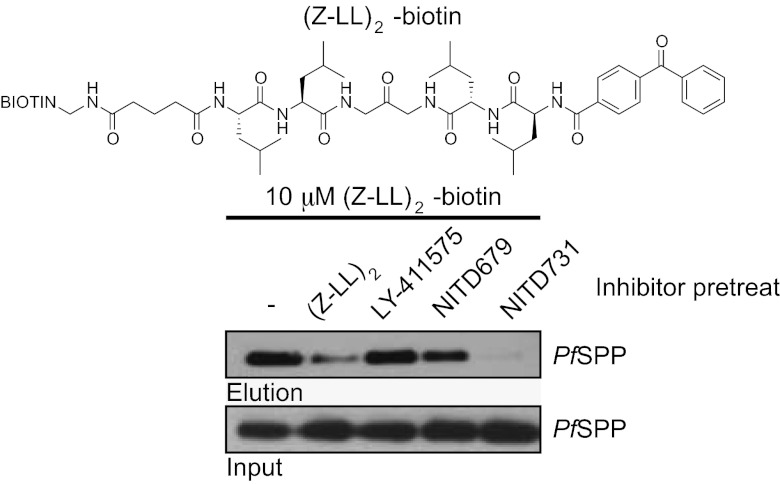

SPP Inhibitors Directly Bind PfSPP in the Malaria Parasite Proteome.

To provide a more direct link between the action of these SPP inhibitors on parasites with the putative endogenous target PfSPP, we synthesized an activity-based probe (ABP) based on the SPP inhibitor scaffold (Z-LL)2. A similar (Z-LL)2 ABP was originally used by Weihofen et al. to discover the SPP class of proteases (19). The (Z-LL)2 ABP contains a benzophenone moiety to allow covalent crosslinking of the probe to its target, as well as a biotin tag for affinity purification. Treating solubilized parasite lysates with our (Z-LL)2 probe confirmed that PfSPP is being directly targeted by (Z-LL)2 and our LY-411575–based compounds (Fig. 4). The first lane of the blot in Fig. 4 shows a successful immunoprecipitation/Western analysis of PfSPP, indicating that PfSPP is targeted by (Z-LL)2. Pretreatment with unbiotinylated (Z-LL)2 effectively competes for labeling of PfSPP against the biotinylated (Z-LL)2 probe, providing confirmation that (Z-LL)2 is not nonspecifically labeling PfSPP. Likewise, LY-411575, NITD679, and NITD731 compete for labeling in manner that is consistent with the relative potency of each compound against the parasite, confirming that these compounds do indeed bind PfSPP within the complex parasite proteome.

Fig. 4.

SPP inhibitors target PfSPP in a complex parasite proteome. Structure of the (Z-LL)2–based ABP used for parasite lysate labeling. Lower: 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate–solubilized membrane proteins were incubated with 10 μM of (Z-LL)2-biotin for 1 h, then irradiated with UV light. (Z-LL)2-biotin–labeled PfSPP was identified via immunoprecipitation/Western analysis using streptavidin agarose for immunoprecipitation and anti-PfSPP for Western blotting. Competition labelings were carried out by pretreating samples with 5× concentration of the indicated inhibitors.

Identification of PfSPP Inhibitor Target by Selection of Resistant Parasites.

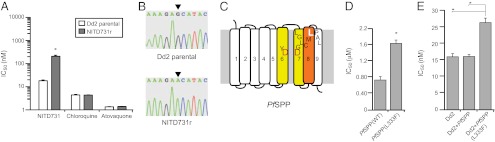

To complement the aforementioned ABP studies, we used also used a chemical–genetic approach to identify the parasite target(s) of NITD731 by the generation and sequencing of resistant parasites. Identification of genetic changes in the resistant parasite line provides details as to the potential molecular target(s) of the compounds in culture, and also other resistance mechanisms not directly related to direct inhibitor binding (34, 35). Drug-resistant parasites were selected by the application of sublethal amounts of the inhibitor over a period of months, with inhibitor concentration increasing concomitantly as parasite resistance increased. We successfully selected for resistant parasites to NITD731 (identified as NITD731r), and the resulting resistant line was found to be more than fivefold more resistant than the parental Dd2 clone (Fig. 5A). Assays of the resistant line with the antimalarial agents chloroquine and atovaquone showed no significant differences in sensitivities to these compounds (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Identification of SPP inhibitor targets in parasites. (A) Parasites grown in sublethal concentrations of NITD731 developed resistance to the compound, resulting in multifold increase in sensitivity vs. that of the parental line. The same parasites did not develop resistance to chloroquine or atovaquone. (B) Sequencing of the PfSPP gene from clones of each of the resistant lines revealed a G-to-A base mutation (in the reverse primer sequence) resulting in the nonsynonymous amino acid change, L333F. (C) The location of the L333 amino acid maps to transmembrane domain 8, upstream of the highly conserved PAL motif. (D) The L333F PfSPP mutant was generated for use in the yeast activity assay and shows a greater than twofold resistance to NITD731. (E) Introduction of the L333F transgene into Dd2 parental parasites confers resistance to NITD731. Transgenic parasites expressing the WT gene were also introduced as a control. Mean IC50 ± SD is shown (*P < 0.05).

To identify a genetic change in the pfspp gene (PF3D7_1457000) that conferred resistance to NITD731, we generated a clonal parasite line from the resistant parasite trial by limiting dilution. Sequencing analysis of the pfspp coding sequence revealed a single nonsynonymous mutation, L333F (Fig. 5B). From the PfSPP coding sequence, it is known that the L333 residue resides in transmembrane domain 8, near the highly conserved PAL motif, a hydrophobic region necessary for activity in SPP and PS (Fig. 5C). Unfortunately, no crystal structural yet exists for PfSPP, hindering predictions on the role of the L333 residue for the mechanism of PfSPP proteolysis.

To ascertain if there were any “off-target” mutations resulting from the in vitro selection protocol, we obtained whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data by using the Illumina platform for NITD731r. For NITD731r, we obtained 42× bulk genomic coverage with 90.8% of the genome covered by five or more high quality bases. This resistant clone was compared with WGS data for the parent Dd2 clone, for which we obtained 24× bulk genomic coverage with 71.0% of the genome covered by five or more high-quality bases. In total, 7,834 high-quality variants were found in the two sequenced strains. Of these variants, 7,831 are found in the parental and the resistant strain, and represent the genetic differences separating Dd2 from the 3D7 reference to which the strains were compared. The remaining three variants represent genetic differences between the parental clone and the resistant clone. One of these is the L333F mutation originally found in pfspp by Sanger sequencing. The other two mutations consist of an intronic mutation in PF3D7_0103500 and a nonsynonymous mutation in PF3D7_1135400 (Table S1). PF3D7_1135400 is annotated as a hypothetical gene in PlasmoDB 9.1, and may represent another direct binding target or may be strictly involved in a unknown resistance mechanism; however, that this gene is purely hypothetical limits our ability to analyze its role in this resistance mechanism.

To confirm the role of the L333F mutation in PfSPP that confers resistance in P. falciparum, we expressed the mutant PfSPP (L333F) in our yeast assay and analyzed the potency of NITD731. The IC50 in the mutant L333F PfSPP showed more than twofold increase vs. that of WT PfSPP (Fig. 5D). This change was not a result of different expression levels of either protein, as the total luminescence of episomally expressed PfSPP and PfSPP L333F was the same (Fig. S6).

We also wished to confirm the importance of this mutation in generating resistance in live parasites. To do this, the L333F PfSPP gene was amplified from cDNA of the resistant parasite line and ligated into an expression vector that would allow for transposase-mediated integration into a parasite genome (36). Transgenic parasites expressing L333F PfSPP or WT PfSPP were generated and were then assayed for replication while in the presence of increasing inhibitor concentrations. The transgenic L333F-expressing parasites showed a statistically significant increase in resistance to NITD731 relative to the parental Dd2 clone. The increase in resistance was not attributed to increased WT PfSPP expression, as parasites transfected with a WT allele showed no increase in its IC50. (Fig. 5E). The modest level of resistance observed in our transgenic line relative to the original drug-selected resistant parasite line may potentially be a result of low expression of the mutant PfSPP and simultaneous presence of the endogenous WT allele in our transgenic parasite lines. However, the data remain statistically significant and also are commensurate with the results of other studies of this kind in P. falciparum. Together, the resistance data from Fig. 5 along with direct binding data in Fig. 4 suggest that PfSPP is indeed a direct target of the lead compound NITD731 and is important to survival of P. falciparum parasites in culture.

NITD731 Is Potent Against Liver-Stage Malaria Parasites as well as Nonmalarial Pathogenic Protozoan Parasites.

Prevention of liver-stage development would lead to true causal prophylaxis and would interrupt transmission. Therefore, we assessed the efficacy of NITD731 against liver-stage parasites by using a high-content imaging assay that allows the investigation of compound efficacy against P. yoelii liver schizonts (37). We found that NITD731 was potent against exoerythrocytic parasites, with a comparable IC50 to that of the antimalarial drug atovaquone, one of the few commonly used antimalarial agents that has efficacy against this stage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of SPP inhibitors on P. yoelii liver-stage parasites

| Compound | Mean P. yoelli EEF IC50 ± SD, μM | HepG2 IC50, μM |

| Atovaquone | 0.0015 ± 0.00090 | >10 |

| NITD731 | 0.0078 ± 0.0018 | >10 |

| NITD679 | 0.047 ± 0.015 | >10 |

| LY-411575 | 0.048 ± 0.032 | >10 |

SPP inhibitor activity was assayed against P. yoelii sporozoites and host HepG2 cells. EEF, exo-erythrocytic form.

Because other apicomplexan and kinetoplastid parasites have SPP orthologues, we also assessed NITD731 against T. cruzi and T. gondii. NITD731 was especially effective against both parasite species (Table 2), suggesting that NITD731 represents a pan-antiprotozoan SPP inhibitor.

Table 2.

Potency of NITD731 against T. cruzi and T. gondii

| Parasite | Mean IC50 ± SD, μM | Host cell | IC50, μM |

| T. cruzi | 0.00081 ± 0.00065 | 3T3 | >10 |

| T. gondii | 0.071 ± 0.011 | U-2 OS | >10 |

T. cruzii amastigote/trypomastigote viability was assayed using bioluminescent determination of β-gal enzyme activity through a coupled reaction with firefly luciferase in parasites that harbor a β-gal gene. T. gondii viability was monitored using a transgenic line expressing a luciferase reporter gene.

Discussion

The identification of novel targets and antiparasitic compounds is a pressing need for infectious diseases of the developing world, and is made all the more urgent by the emergence of drug-resistant parasites. Here we show that the ERAD pathway represents an exploitable vulnerability in P. falciparum and other protozoan parasites. The absence of many mammalian ERAD orthologues in protozoans contrasts with the mammalian system, which is characterized by an integrated and redundant network topology. The potential lack of redundancy of the ERAD network in parasites may be manifested by their heightened sensitivities to the inhibitors of ERAD components relative to mammalian cells.

Of the candidate parasite ERAD targets, we confirmed a role for PfSPP in the turnover of an unstable membrane protein. The precise function of PfSPP in the recognition and degradation of aberrant membrane proteins remains unanswered. As SPP is a multipass transmembrane protein, it is tempting to think of SPP as a channel through which ERAD substrates translocate into the cytosol, the molecular identity of which has not yet been conclusively identified (38). However, this scenario is complicated by the protease active site that fills the hydrophilic intramembrane cavity of SPP.

We also show that PfSPP can be directly targeted by highly potent small molecules in P. falciparum by using a chemical biology approach, and that a single nonsynonymous point mutation within PfSPP was selected for by passage of parasites at sublethal doses of compound. In the generation of this resistant parasite, there was hypothetical protein that was found to contain nonsynonymous mutation. Given the purely hypothetical nature of this gene, it is hard to predict whether the corresponding protein is a direct target of NITD731 or is playing an indirect role in resistance, although, given its structure, it would not appear to be a channel or transporter.

Although an enzyme that may be essential to a pathological organism does not guarantee it is a suitable drug target, we believe focusing on PfSPP is worthwhile for several reasons. Perhaps most promisingly, there exists an extensive drug-discovery repositioning opportunity for potential SPP inhibitors in existing chemical libraries from pharmaceutical companies. PS and SPPs are part of the A22-family integral membrane aspartyl proteases; it is therefore likely that there exist numerous potent PfSPP drug-like inhibitors in PS-directed chemical libraries, reducing cost barriers for development (39–41). Indeed, LY-411575 was a product of previous a PS drug-discovery effort.

Worries about host toxicity by SPP inhibition are mitigated by the fact that knockdown of SPP is nonlethal in human cell lines. Furthermore, SPP inhibitors showed no toxicity when assayed against human cell lines (HepG2, 3T3, U-2 OS) as shown here, indicating a potential high therapeutic index for this class of compounds. Future screening against γ-secretase and PfSPP to identify compounds with activity biased toward PfSPP would help reduce risks associated with inhibition of Notch processing and other activities of γ-secretase.

Finally, our lead compound is lethal to chloroquine-resistant blood-stage P. falciparum, as well as liver-stage malaria parasites, with an IC50 against both stages that is comparable with only that of the antimalarial drug atovaquone. This suggests that PfSPP represents a causal prophylactic and transmission-blocking antimalarial target. It is also highly potent against a spectrum of pathogenic protozoan parasites. Thus, although further screening of drug-like molecules or medicinal chemistry optimization may be necessary for species-specific targeting and improved pharmacodynamic parameters, inhibition of SPP may represent a valid pan-antiprotozoan drug discovery strategy.

Materials and Methods

Details of parasite culture, including transfections, IC50 determinations, resistance generation, and WGS, as well as cell-based assays, are provided in SI Materials and Methods. Data were retrieved from the following sources: (i) National Center for Biotechnology Information (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), (ii) PlasmoDB (http://plasmodb.org/plasmo), (iii) TriTrypDB (http://tritrypdb.org/tritrypdb), and (iv) ToxoDB (http://toxodb.org/toxo). Database homology searching was performed by using OrthoMCL (www.orthomcl.org), BLASTP, and profile hidden Markov algorithms (42). Full methods are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Aaron Gitler (Stanford University), Michael Klemba (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University), and Randall Pittman (University of Pennsylvania) for advice and reagents. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants T32AI007532 (to M.B.H.) and 1R56AI081797-01 (to D.C.G.), the University of Pennsylvania Transdisciplinary Awards Program in Translational Medicine and Therapeutics Pilot Program (D.C.G.), the Penn Genome Frontiers Institute, Wellcome Trust Grant WT078285 (to D.C.G.), and support from the Medicines for Malaria Venture to the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation and the Novartis Institute for Tropical Diseases.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1216016110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dondorp AM, et al. The threat of artemisinin-resistant malaria. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1073–1075. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1108322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maier AG, Cooke BM, Cowman AF, Tilley L. Malaria parasite proteins that remodel the host erythrocyte. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(5):341–354. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MH, Ploegh HL, Weissman JS. Road to ruin: Targeting proteins for degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 2011;334(6059):1086–1090. doi: 10.1126/science.1209235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334(6059):1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travers KJ, et al. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2000;101(3):249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho P, Goder V, Rapoport TA. Distinct ubiquitin-ligase complexes define convergent pathways for the degradation of ER proteins. Cell. 2006;126(2):361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christianson JC, et al. Defining human ERAD networks through an integrative mapping strategy. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(1):93–105. doi: 10.1038/ncb2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozdech Z, et al. The transcriptome of the intraerythrocytic developmental cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 2003;1(1):E5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward P, Equinet L, Packer J, Doerig C. Protein kinases of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum: The kinome of a divergent eukaryote. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fennell C, et al. PfeIK1, a eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha kinase of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, regulates stress-response to amino-acid starvation. Malar J. 2009;8:99. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang M, et al. PK4, a eukaryotic initiation factor 2α(eIF2α) kinase, is essential for the development of the erythrocytic cycle of Plasmodium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(10):3956–3961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121567109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gosline SJ, et al. Intracellular eukaryotic parasites have a distinct unfolded protein response. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e19118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egorin MJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution, and metabolism of 17-(dimethylaminoethylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (NSC 707545) in CD2F1 mice and Fischer 344 rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2002;49(1):7–19. doi: 10.1007/s00280-001-0380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banumathy G, Singh V, Pavithra SR, Tatu U. Heat shock protein 90 function is essential for Plasmodium falciparum growth in human erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(20):18336–18345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pallavi R, et al. Heat shock protein 90 as a drug target against protozoan infections: Biochemical characterization of HSP90 from Plasmodium falciparum and Trypanosoma evansi and evaluation of its inhibitor as a candidate drug. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(49):37964–37975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.155317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffstrom BG, et al. Inhibitors of protein disulfide isomerase suppress apoptosis induced by misfolded proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6(12):900–906. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou TF, et al. Reversible inhibitor of p97, DBeQ, impairs both ubiquitin-dependent and autophagic protein clearance pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(12):4834–4839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung DW, Ponts N, Prudhomme J, Rodrigues EM, Le Roch KG. Characterization of the ubiquitylating components of the human malaria parasite’s protein degradation pathway. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e43477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weihofen A, Binns K, Lemberg MK, Ashman K, Martoglio B. Identification of signal peptide peptidase, a presenilin-type aspartic protease. Science. 2002;296(5576):2215–2218. doi: 10.1126/science.1070925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loureiro J, et al. Signal peptide peptidase is required for dislocation from the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature. 2006;441(7095):894–897. doi: 10.1038/nature04830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stagg HR, et al. The TRC8 E3 ligase ubiquitinates MHC class I molecules before dislocation from the ER. J Cell Biol. 2009;186(5):685–692. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SO, et al. Protein disulphide isomerase is required for signal peptide peptidase-mediated protein degradation. EMBO J. 2010;29(2):363–375. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bagola K, Mehnert M, Jarosch E, Sommer T. Protein dislocation from the ER. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(3):925–936. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crawshaw SG, Martoglio B, Meacock SL, High S. A misassembled transmembrane domain of a polytopic protein associates with signal peptide peptidase. Biochem J. 2004;384(pt 1):9–17. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schrul B, Kapp K, Sinning I, Dobberstein B. Signal peptide peptidase (SPP) assembles with substrates and misfolded membrane proteins into distinct oligomeric complexes. Biochem J. 2010;427(3):523–534. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krawitz P, et al. Differential localization and identification of a critical aspartate suggest non-redundant proteolytic functions of the presenilin homologues SPPL2b and SPPL3. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(47):39515–39523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casso DJ, Tanda S, Biehs B, Martoglio B, Kornberg TB. Drosophila signal peptide peptidase is an essential protease for larval development. Genetics. 2005;170(1):139–148. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.039933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marapana DS, et al. Malaria parasite signal peptide peptidase is an ER-resident protease required for growth but not invasion. Traffic. 2012;13(11):1457–1465. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Booth C, Koch GL. Perturbation of cellular calcium induces secretion of luminal ER proteins. Cell. 1989;59(4):729–737. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srivastava IK, Rottenberg H, Vaidya AB. Atovaquone, a broad spectrum antiparasitic drug, collapses mitochondrial membrane potential in a malarial parasite. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(7):3961–3966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiwari S, Weissman AM. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation of T cell receptor subunits. Involvement of ER-associated ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s) J Biol Chem. 2001;276(19):16193–16200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007640200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong X, Pittman RN. Ataxin-3 binds VCP/p97 and regulates retrotranslocation of ERAD substrates. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(16):2409–2420. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, et al. Plasmodium falciparum signal peptide peptidase is a promising drug target against blood stage malaria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380(3):454–459. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rottmann M, et al. Spiroindolones, a potent compound class for the treatment of malaria. Science. 2010;329(5996):1175–1180. doi: 10.1126/science.1193225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nzila A, Mwai L. In vitro selection of Plasmodium falciparum drug-resistant parasite lines. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(3):390–398. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balu B, Shoue DA, Fraser MJ, Jr, Adams JH. High-efficiency transformation of Plasmodium falciparum by the lepidopteran transposable element piggyBac. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(45):16391–16396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504679102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meister S, et al. Imaging of Plasmodium liver stages to drive next-generation antimalarial drug discovery. Science. 2011;334(6061):1372–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1211936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braakman I, Bulleid NJ. Protein folding and modification in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:71–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062209-093836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfe MS. Inhibition and modulation of gamma-secretase for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5(3):391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weihofen A, et al. Targeting presenilin-type aspartic protease signal peptide peptidase with gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(19):16528–16533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato T, et al. Signal peptide peptidase: Biochemical properties and modulation by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Biochemistry. 2006;45(28):8649–8656. doi: 10.1021/bi060597g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR. HMMER Web server: Interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Web server issue):W29–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.