The authors maintain that laparoscopic diverticulectomy is a safe and feasible option that should be offered for patients with symptomatic gastric diverticulum.

Keywords: Laparoscopic gastric diverticulectomy, Abdominal pain, Dysphagia, Gastric, Diverticulum, Paraesophageal, Hernia stomach

Abstract

Background:

Gastric diverticulum (GD) is an extremely rare disorder that can easily be overlooked when investigating the cause of abdominal pain. Its diagnosis is founded on a history of gastrointestinal symptoms and a typically unrevealing physical examination, and diagnosis requires confirmation from UGI contrast studies, EGD, and CT scan. Symptomatic GD should be kept in consideration as a cause of abdominal issues, because not only is it treatable, but also complications of GD can be life threatening. The surgical treatment of GDs has evolved from thoraco-abdominal incisions in the early twentieth century to the laparoscopic approach used today.

Case Report:

The patient is a 45-y-old male presenting with a 4-mo case of dysphagia, small amounts of regurgitation, and abdominal pain but no other symptoms.

Results:

The patient was diagnosed with a gastric diverticulum, which was subsequently successfully treated with a laparoscopic gastric diverticulectomy.

Conclusion:

Laparoscopic gastric diverticulectomy is a safe procedure and should be considered as an option to treat symptomatic GD.

INTRODUCTION

A 45-y-old white male with no significant past medical history presented to his primary care physician with a 4-mo case of dysphagia, with associated intermittent regurgitation of solid foods in small amounts. He also suffered from intermittent abdominal discomfort primarily in the epigastric region. He indicated that he had no other symptoms, such as gastroesophageal reflux, fevers, weight changes, or any other gastrointestinal concerns.

His physical examination showed no significant findings. He appeared healthy and younger than his stated age and had a BMI of 23.5. His abdominal examination was unremarkable.

CASE REPORT

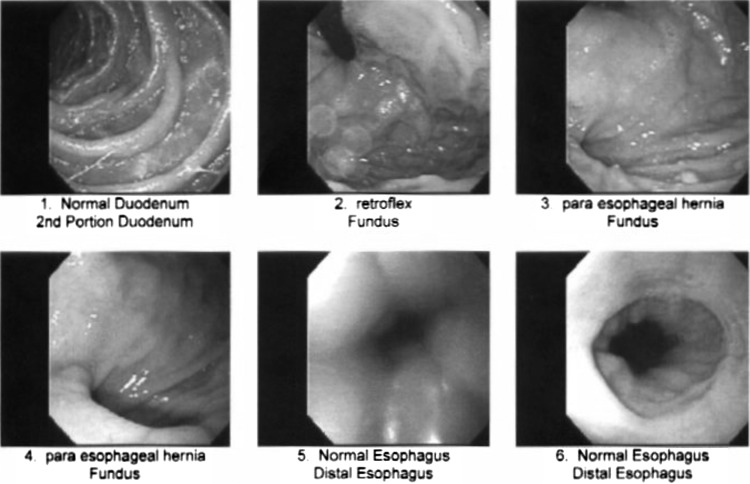

Initially, an EGD was performed that suggested a small paraesophageal hernia, but no other abnormality was identified (Figure 1). An upper gastrointestinal (UGI) contrast study demonstrated no paraesophageal hernia, but a 3-cm gastric diverticulum was identified along the fundus of the stomach (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

EGD findings. The patient's gastric diverticulum was misdiagnosed as a paraesophageal hernia.

Figure 2.

UGI contrast image of the gastric diverticulum.

Based on the patient's presentation and UGI findings, it was felt that the gastric diverticulum was the source of the patient's symptoms. He was subsequently taken to the operating room where a laparoscopic gastric diverticulectomy was successfully performed.

After general endotracheal anesthesia was initiated, the patient was placed in a modified lithotomy position and a nasogastric tube was inserted. A Veress needle was utilized to create the initial pneumoperitoneum with subsequent placement of all working ports. A liver retractor was used to adequately retract the left lobe of the liver. The greater curvature of the stomach was then mobilized by taking the short gastric arteries with a Harmonic scalpel. The stomach was rotated to expose the posterior aspect, eventually identifying the splenic hilum. Using blunt dissection, the GD began to come into view. The diverticulum was further posterior than anticipated, and this required complete mobilization of the posterior fundus. It was further freed from surrounding tissue with the Harmonic scalpel and blunt dissection. Next, a laparoscopic stapling device with staple-line reinforcement was used to fire across the gastric diverticulum including normal stomach tissue. The GD was then successfully retrieved with a laparoscopic pouch. The staple line was then carefully examined and tested by submerging the insufflated stomach under sterile irrigation to observe for bubbles. No evidence of a leak was present, and the insufflated stomach was then aspirated through the nasogastric tube.

The patient had an uneventful postoperative course. He was placed on a regular diet on postoperative day 2 and discharged to home on postoperative day 3. On his first follow-up visit, the patient was doing very well with no further symptoms.

DISCUSSION

When a symptomatic diverticulum arises in the stomach, it can become “a wayside house of ill fame,” as described by Michel in 1950.1 GDs are extremely rare but have been mentioned throughout the literature dating back to the first known descriptions by Moebius in 1661 and later by Roax in 1774.2 In one study, 0.02% of autopsies demonstrated GDs, and 0.04% of gastric radiographic examinations identified GDs.3 Rivers, Stevens, and Kirklin demonstrated a total of 14 reports of gastric diverticula; 4 came from 3,662 necropsies, and 10 were resected out of 11,234 exploratory laparotomies from the Mayo Clinic.4 Despite the potential presence of a GD throughout the life of a patient, the literature suggests that most symptomatic GDs are found in patients between 20 and 60 y.3,5 They are even more rare in the young; one study showed that only 4% of GDs occurred in patients below the age of 20.3 Furthermore, they are thought to have an equal incidence in males and females.6,7 Despite their rarity, GDs are important to keep in mind during diagnosis, as they harbor the same potential complications of other gastrointestinal diverticula, such as hemorrhage, perforation, obstruction, and malignancy, all of which can be life threatening.

Schmidt and Walters8 classified GDs as either true (congenital) diverticula or false (acquired) diverticula. False diverticula were further characterized as either the pulsation type or the traction type. True diverticula possess all layers of the gastric wall, and it is believed that these congenital diverticula occur as a result of the splitting of the longitudinal muscular fibers at the level of the cardia, leaving only the circular muscle fibers present in the gastric wall and thus creating a weakening that allows the diverticula to form during the fetal period. Fetal GDs have been reported by Reich,9 and Lewis described gastrointestinal diverticula in embryos as early as 1908.10 False diverticula, also known as acquired diverticula, do not carry all layers of the gastric wall. Pulsation diverticula are those that arise from increased intraluminal pressure, such as chronic coughing, obesity, and pregnancy. Traction diverticula arise from perigastric adhesions from concurrent diseases, such as peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, malignancy, gastroesophageal reflux, and cholecystitis.3,5

Most congenital diverticula (75%) are located on the cardia of the stomach, usually on the posterior wall below the GE junction.11 According to Michel, 65% of GDs are located near the lesser curvature of the posterior cardia.1 Most acquired GDs occur along the greater curvature of the antrum.7,11 However, GDs can arise virtually anywhere along the stomach.

GDs usually occur as an independent phenomenon, though there are reports of multiple GDs in patients.7 They have been described as pear-shaped, unilocular, and multilocular.1 Their necks can be small or wide, and it has been suggested that the size of the neck plays a role in whether or not symptoms will develop. Wide-neck GDs often go unnoticed perhaps because food and digestive juices are less likely to become trapped in the diverticula as easily as in a narrow-neck GD. Most true GDs are <2cm, with a range of 1cm to 3cm.7

Symptoms of GD are fairly consistently described throughout the literature. Vague upper abdominal and epigastric pain were present in 18% to 30% of cases,12 and patients also present with anorexia,13 nausea and vomiting,1 and even dysphagia.14 It has been suggested that food retention with subsequent distension of the GD could cause the pain.15,16 Food retention with subsequent release of gastric juices within the GD would cause inflammation leading to diverticulitis and possibly ulceration or hemorrhage.

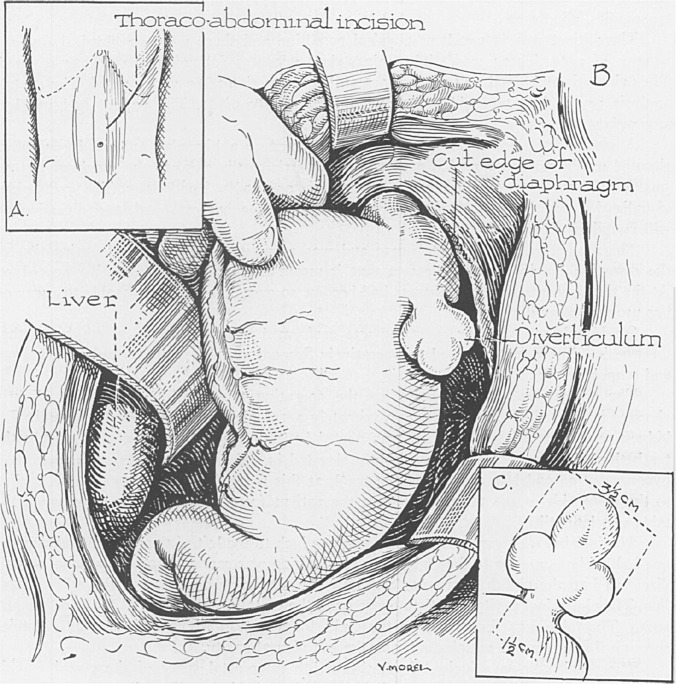

A GD diagnosis can be confirmed with UGI contrast studies, computed tomography scans, and upper endoscopies. It is paramount to obtain a lateral view on UGI contrast studies to observe the out-pouching of the diverticula on the posterior wall of the stomach (Figure 2).17 CT scans are also used to diagnose GDs; however, GDs have also been mistaken for adrenal masses.18 Most authors recommend EGD to confirm or rule out GDs, as this modality easily confirms the location and size of the GD and provides the opportunity to biopsy any concurrent pathology.

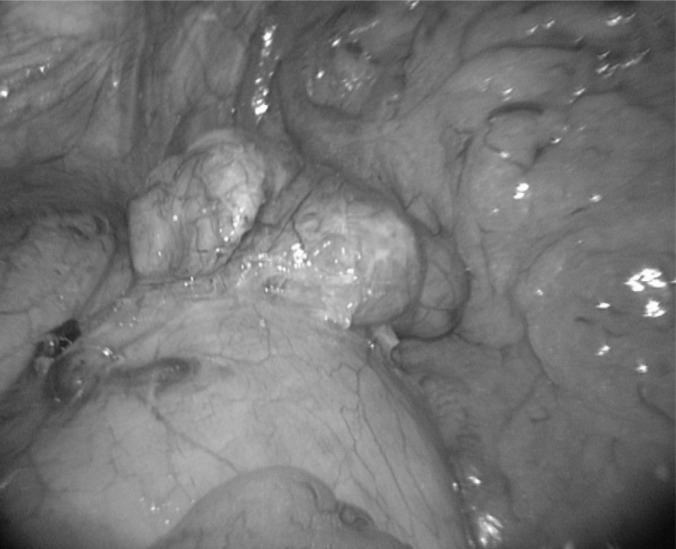

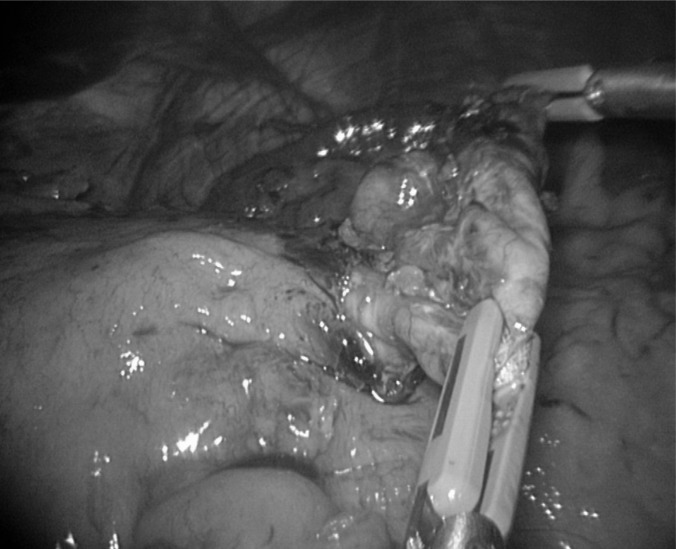

The treatment of a GD ranges from leaving asymptomatic GDs alone to treating symptomatic GDs with antacid therapy or surgery. Asymptomatic GDs do not require any treatment. However, routine surveillance with a periodic history and physical is recommended, given the potential for complications. Some authors support conservative therapy with antiacids,19 with the understanding that relief may be temporary. Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for symptomatic GD, with over 2/3 of patients remaining symptom-free after surgery.20 Several surgical approaches have been described including invagination of the GD as well as partial gastrectomy.21,22 In the mid 1900s, Humphreys advocated thoraco-abdominal incisions owing to their high posterior position on the cardia of the stomach (Figure 3).1,23 However, Walters at the same time supported an abdominal approach for surgeons more familiar with technical approaches to foregut pathology.24 Since the first successful laparoscopic resection in the late 1990s, this approach is now considered safe and feasible.13 Intraoperative endoscopy should be strongly considered for finding an elusive GD,13,14,25 as reoperation for posterior GDs have been reported26 (Figures 4, 5, and 6 show intraoperative photographs from our case report).

Figure 3.

Exposure of a trilocular gastric diverticulum through an abdominal thoracic incision (reproduced with permission from Michel M. Trilocular Gastric Diverticulum. Ann Surg. 1950.).

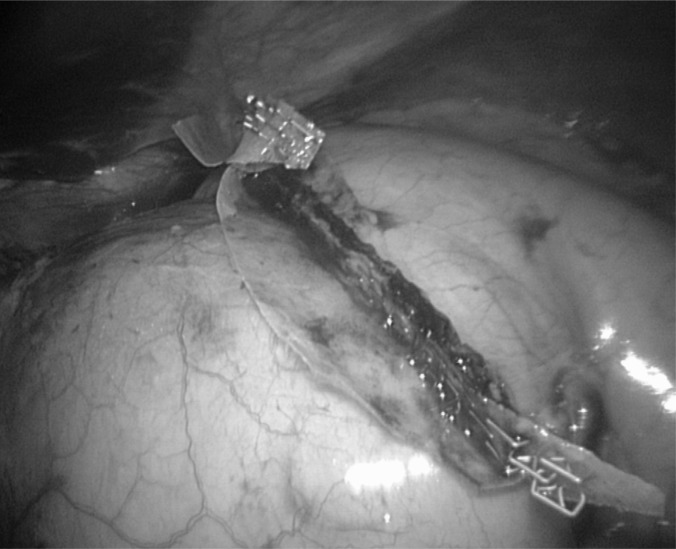

Figure 4.

Laparoscopic view of the posterior multilocular gastric diverticulum. Voeller, 2010.

Figure 5.

Exposure of the neck of the diverticulum for preparation of diverticulectomy. Voeller, 2010.

Figure 6.

Staple line of the gastric diverticulectomy. Voeller, 2010.

CONCLUSION

In summary, GDs remain a rarity in the etiology of abdominal pain, though it is a diagnosis that should certainly be considered for the patient with epigastric symptoms when all other more common pathologies have been ruled out. UGI and EGD play important roles in the diagnosis of GDs. Laparoscopic diverticulectomy is a safe and feasible operation that should be offered for symptomatic GD.

References:

- 1. Michel M, Williams W. Trilocular gastric diverticulum: treated by surgical extirpation through thoraco-abdominal incision. Ann Surg. 1950; 273–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moses WR. Diverticula of stomach. Arch Surg. 1946;52:59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Palmer ED. Collective review: gastric diverticula. Int Abstr Surg. 1951; 92: 417–428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rivers AB, Stevens GA, Kirklin BR. Diverticula of stomach. SGO. 1935;60:106 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schweiger F, Noonan J. An unusual case of gastric diverticulosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991; 86: 1817–1819 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donkervoort SC, Baak LC, Blaauwgeers JL, et al. Laparoscopic resection of a symptomatic gastric diverticulum: a minimally invasive solution. JSLS. 2006; 10: 525–527 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harford W, Jeyarajah R. Diverticula of the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. In: Feldman M, Friedman L, Brandt L, et al. eds. Sleisenger & Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 8th ed Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2006; 465–477 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmidt HW, Walters W. Diverticula of stomach. Surg Gynec Obst. 1935;60:106 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reich NE. Gastric Diverticula. Am J Dig Dis. 1941;8:70 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewis FT, Thyng FW. Regular occurrence of intestinal diverticula in embryos of pig, rabbit and man. Am J Anat. 1908;7:505 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kubiak R, Hamill J. Laparoscopic diverticulectomy in a 13-year-old girl. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006; 16: 29–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meeroff M, Gollan JRM, Meeroff JC. Gastric diverticulum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1967; 47: 189–203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fine A. Laparoscopic resection of a large proximal gastric diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998; 48: 93–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vogt DM, Curet MJ, Zucker KA. Laparoscopic management of gastric diverticula. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Technol. 1999; 9: 405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kilkenny JW., III Gastric diverticula: it's time for an updated review. Gastroenterology. 1995; 108: A1226 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tillander H, Hesselsjo R. Juxtacardia gastric diverticula and their surgery. Acta Chir Scand. 1968; 134: 255–264 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eastwood SR. Diverticulum of the stomach. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1929; 1234–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwartz AN, Goiney RC, Graney DO. Gastric diverticulum simulating an adrenal mass: CT appearance and embryogenesis. Am J Roentgenol. 1986; 146: 553–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rodeberg DA, Zaheer S, Moir CR, et al. Gastric diverticulum: a series of four pediatric patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002; 34: 564–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Palmer E. Gastric diverticulosis. Am Fam Phys. 1973; 7: 114–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brian JE, Jr., Stair JM. Noncolonic diverticular disease. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985; 161: 189–195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cosman B, Kellum J, Kingsbury H. Gastric diverticula and massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Surg. 1957; 94: 144–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Humphreys GH. An approach to resections of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Ann Surg. 1946;I24:288 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Walters W. Diverticula of the stomach. JAMA. 1946;131:954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim SH, Lee SW, Choi WJ, et al. Laparoscopic resection of gastric diverticulum. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Technol. 1999; 9: 87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith RS, Mortensen JD. Diverticula gastric cardia. NW Med. 1949; 48: 185–188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]