The pathology of postoperative granulomatous peritonitis is poorly understood, but a hypersensitivity reaction may be a likely mechanism. A patient's history is important, because surgeons should be aware of this rare cause of ascites.

Keywords: Granulomatous peritonitis, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Abstract

Background:

Granulomatous peritonitis may indicate a number of infectious, malignant, and idiopathic inflammatory conditions. It is a very rare postoperative complication, which is thought to reflect a delayed cell-mediated response to cornstarch from surgical glove powder in susceptible individuals. This mechanism, however, is much more likely to occur with open abdominal surgery when compared with the laparoscopic technique.

Methods:

We report a case of sterile granulomatous peritonitis in an 80-y-old female after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Management was conservative, and no relapse was observed after over 1-y of follow-up.

Discussion:

We propose that peritoneal exposure to bile acids during the laparoscopic removal of the gallbladder was the trigger of granulomatous peritonitis in this patient. Severe complications, such as peritoneal adhesions, intestinal obstruction, and fistula formation, were observed, but no fatalities were reported.

Conclusion:

We should be aware of this rare cause of peritonitis in the surgical setting.

INTRODUCTION

Granulomatous peritonitis has been described as a rare postoperative complication with clinical presentations, varying from life-threatening ascites to mild and nonspecific abdominal pain.1 Histologically, this disorder is characterized by a granulomatous reaction that is thought to reflect a delayed cell-mediated response in individuals hypersensitive to cornstarch.1 This indefinable condition is often confused with a malignancy, and a wide spectrum of infectious and noninfectious causes of peritoneal involvement need to be ruled out. The clinical relevance of granulomatous peritonitis is still undefined in the field of laparoscopic surgery, and its pathophysiology also remains uncertain. We report the case of a patient with severe, self-remitting granulomatous peritonitis following laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

CASE REPORT

An 80-y-old woman presented with a 2-wk history of lower abdominal pain, low-grade fever, and progressive abdominal swelling. A laparoscopic cholecystectomy had been performed 20 d earlier to remove gallstones; no gross bile contamination of the peritoneum or any obvious bile leaks were detected. In addition, no peritoneal or omental nodules were observed at that time. The postoperative course was unremarkable except for poor glycemic control that was managed with intravenous fluids and regular insulin. The patient was discharged free of symptoms 5 d after surgery. Her medical history included hypertension and diabetes that were controlled with glimepiride and ramipril. She denied taking any other drugs, including over-the-counter drugs, recreational medications, or herbal remedies, and had no personal or family history of gastrointestinal and liver disorders, serositis, or allergies.

Physical examination was normal except for a distended and diffusely tender abdomen with a shifting dullness. White blood cells (WBCs) were 12.8 × 103/L (normal, 4–10 × 103/L) with a normal differential value, erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 90mm/hr, and C-reactive protein levels were 12mg/dL (normal <0.5mg/dL). The remaining variables, including enzymes and liver and kidney function tests, were normal. An electrocardiogram and a transthoracic echocardiography were also normal. Ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging revealed abundant ascites and diffuse thickening of the omentum.

A paracentesis value of 1500mL showed that ascitic fluid contained 8200WBCs/mm3, with a normal differential and no malignant cells. Bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal culture and staining, were negative. Since abdominal swelling and tenderness were deteriorating, we performed a laparoscopy with a midline incision that revealed a large amount (4000mL) of green, turbid fluid in the peritoneal cavity along with diffuse and nodular thickening of the peritoneum and omentum. Microscopy of peritoneal biopsies showed many noncaseating, eosinophil-rich granulomas with sparse multinucleated foreign body giant cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages (Figure 1). Starch granules, vasculitis, and thrombosis were not present. There were also no signs of viral cytopathic effects or intracellular parasites. Special stains and cultures for microorganisms were also negative.

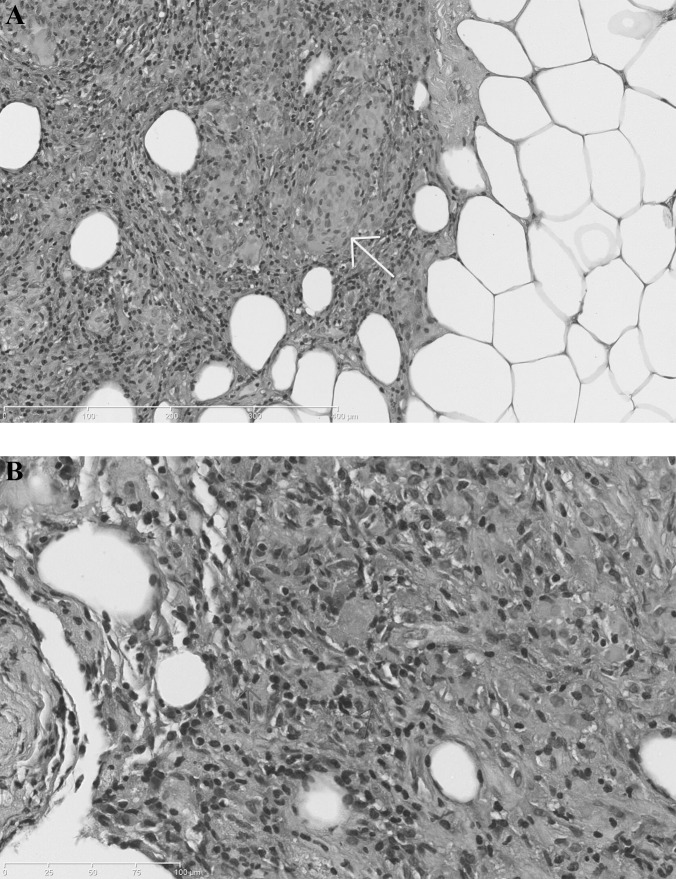

Figure 1.

Full-thickness biopsy specimen of the peritoneum. Fibrous-adipose tissue fragments partially lined by mesothelial cells with epithelioid giant cells granulomas (arrow) (Panel A, hematoxylin and eosin, 5 x). A higher-power view (40 x) shows numerous eosinophils (arrows), which are characteristically deep pink on staining with hematoxylin and eosin (Panel B).

After administering furosemide (50 mg daily) and spironolactone (100 mg daily for 2 wk), the patient recovered and no longer showed symptoms. Ultrasonography showed no ascites and diuretics were gradually tapered and interrupted after 6 wk. One year later, the patient was examined and appeared well with no evidence of ascites or active serositis.

DISCUSSION

Massive ascites was caused in this patient by a sterile granulomatous peritonitis that developed a few weeks after a minor laparoscopic cholecystectomy. She had no prior liver disease or any other risk factors for ascites. We also ruled out infectious, malignant, and idiopathic inflammatory conditions, including tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Crohn's disease, Wegener's granulomatosis, and lymphoproliferative disorders that may suggest granulomatous peritonitis. Clinical and pathological features as well as the timeline of the condition we observed in our patient were similar to those described in other reports on this rare postoperative complication.1 Of note is that only one previous report describes a patient who underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.2 The true extent of the incidence of postoperative granulomatous peritonitis is unknown, because milder cases may go undetected.

Laparoscopic surgery may affect both the integrity and biology of the peritoneum through a range of different mechanisms. Examples are increased abdominal pressure, insufflation of gases, most notably CO2, use of dissection devices, duration of procedure and temperature shifts, ultimately leading to peritoneal hypoxia, acidosis, and cell apoptosis.3 There is evidence from experimental models that a pneumoperitoneum, particularly if created with either CO2 or helium, may downregulate the inflammatory response after laparoscopic surgery through decreased production and release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 and increased production of transforming growth factor-β.4–6 CO2 pneumoperitoneum may also be associated with an increased formation of postoperative adhesions.7 Despite these advances in our knowledge of peritoneal metabolism and immunology, the pathophysiology of postoperative granulomatous peritonitis remains poorly understood with a hypersensitivity reaction being the most likely mechanism.8

Spillage of bile, sludge, or gallstones may occur during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, but they generally have no detrimental consequences in most patients. Of note, the peritoneal granulomas from the patient described by Merchant and colleagues2 stained for bile suggest that peritoneal exposure to bile acids may trigger a florid granulomatous reaction in susceptible individuals. This view is indirectly supported by the observation that the spillage of abdominal cysts into the peritoneal cavity during open or laparoscopic removal may also elicit a granulomatous inflammation of the peritoneum.9,10 Remarkably, no gross bile contamination of the peritoneum or an obvious bile leak was detected in our patient during the laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

The accidental intraperitoneal introduction of talc or corn starch from surgical glove powder has the potential to trigger a delayed hypersensitivity inflammatory response with formation of foreign body granulomas, peritoneal fibrosis, and ascites.1 The starch granules are usually readily identified in tissue sections when polarized light, periodic acid-Schiff, or iodine stains are used.1 This mechanism is more likely to occur with open than with laparoscopic surgery. In addition, talc or cornstarch granules were not seen in biopsy samples of peritoneum from our patient. Moreover, magnesium oxide and magnesium carbonate powder, added in concentrations varying between 2% and 30% as dispersing agents to the starch, may themselves produce a foreign body reaction that represents an additional confounding point.8 Other potential triggers of a hypersensitivity granulomatous reaction involving the peritoneum include chemical antiseptics, such as octenidine dihydrochloride and phenoxyethanol, which are commonly used for peritoneal lavage during abdominal surgery, iodinated contrast media used for hysterosalpingography, and cotton lint from disposable surgical drapes and laparotomy pads.11–13 Peritoneal dialysis may also cause granulomatous peritonitis.8

It is still unknown if the presentation and clinical course of postoperative granulomatous peritonitis is similar to those of other immune-mediated inflammatory peritoneal disorders, but observations from our case suggest they may differ. For example, our patient had no recurrence of ascites after the peritoneal fluid was mechanically removed, so we decided not to start the patient on corticosteroids or any other anti-inflammatory therapy. Watchful observation confirmed she achieved a full and complete recovery, and this spontaneous remission was maintained after more than 1-y of follow-up.

The risk of long-term sequelae in postoperative granulomatous peritonitis is still unknown. Severe complications, such as peritoneal adhesions, intestinal obstruction, and fistula formation have been described.1,14 However, no fatalities have been reported so far.1,14 Corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like indomethacin have been used in the treatment of this disorder, but it is unclear whether these strategies could prevent the formation of adhesion and fistulas.1

Contributor Information

Giuseppe Famularo, Internal Medicine, San Camillo Hospital, Rome, Italy..

Daniele Remotti, Pathology, San Camillo Hospital, Rome, Italy..

Michele Galluzzo, Radiology, San Camillo Hospital, Rome, Italy..

Laura Gasbarrone, Internal Medicine, San Camillo Hospital, Rome, Italy..

References:

- 1. Juaneda I, Moser F, Eynard H, Diller A, Caeiro E. Granulomatous peritonitis due to the starch used in surgical gloves. Medicina (B Aires). 2008; 68 (3): 222–224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Merchant SH, Haghir S, Gordon GB. Granulomatous peritonitis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy mimicking pelvic endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 96 (5): 830–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brokelman WJA, Lensvelt M, Borel Rinkes LHM, et al. Peritoneal changes due to laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25 (1): 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moehrlen U, Schwoebel F, Reichmann E, Stauffer U, Gitzelmann CA, Hamacher J. Early peritoneal macrophage function after laparoscopic surgery compared with laparotomy in a mouse model. Surg Endosc. 2005; 19 (7): 958–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. West MA, Hackam DJ, Baker J, Rodriquez JL, Bellingham J, Rotstein OD. Mechanism of decreased in vitro murine macrophage cytokine release after exposure to carbon dioxide: relevance to laparoscopic surgery. Ann Surg. 1997; 226 (2): 179–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mathew G, Watson DI, Ellis TS, Jamieson GG, Rofe AM. The role of peritoneal immunity and the tumour-bearing state on the development of wound and peritoneal metastases after laparoscopy. Aust NZ J Surg. 1999; 69 (1): 14–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Molinas CR, Campo R, Elkelani OA, Binda MM, Carmeliet P, Oninckx PR. Role of hypoxia-inducible factors 1 alpha and 2 alpha in basal adhesion formation and in carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum-enhanced adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery in transgenic mice. Fertil Ster. 2003;80(Suppl. 2):795–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dobbie JW. Serositis: comparative analysis of histological findings and pathogenetic mechanisms in nonbacterial serosal inflammation. Perit Dial Int. 1993; 13 (4): 256–269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kondo W, Bourdel N, Cotte B, et al. Does prevention of intraperitoneal spillage when removing a dermoid cyst prevent granulomatous peritonitis? BJOG. 2010; 117 (8): 1027–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takeuchi K, Deguchi M, Oki Y, Takekida S, Hamana S, Maruo T. Granulomatous chemical peritonitis on the ileocecum after laparoscopic surgery of an ovarian mature cystic teratoma: case report. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 29 (3): 185–186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Papp Z. Postoperative ascites associated with intraperitoneal antiseptic lavage. Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 105 (5): 1267–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eisenberg AD, Winfield AC, Page DL, et al. Peritoneal reaction resulting from iodinated contrast material: comparative study. Radiology. 1989; 172 (1): 149–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Janoff K, Wayne R, Huntwork B, Kelley H, Alberty R. Foreign body reactions secondary to cellulose lint fibers. Am J Surg. 1984; 147 (5): 598–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liebowitz D, Valentino LA. Exogenous peritonitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984; 6 (1): 45–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]