Abstract

Her2/neu is a protooncogene often amplified and overexpressed in ovary and breast cancer cells. HER2/neu receptors - HER2/neu gene expression products stimulate signal transduction pathways leading to increased cell proliferation. The level of its expression is associated with cancer malignancy. Therefore, HER2/neu is an important indicator of cancer malignancy, as well as, a target for antibody guided cancer therapies. The main objective of this work was to develop molecular probes, which would report levels of HER2/neu gene expression and anatomical distribution of its products in vivo. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is particularly suitable for this endeavor, as it offers not only the best spatial resolution from all in vivo imaging modalities currently available, but also the topographic reference for location of these probes within anatomy of the human body. Superparamagnetic single chain variable fragment (scFv) antibodies targeting HER2/neu receptors were genetically engineered. They warranted high labeling specificity and affinity revealed with EDXSI, as well as, induced significant changes in relaxivity detected with NMR. This study demonstrated a proof of concept for using superparamagnetic scFvs in diagnostic evaluation of levels of gene expression products with NMR and MRI for planning receptor targeted therapies.

Keywords: HER2/neu, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, signal transduction, genetically engineered single chain variable fragment antibodies

INTRODUCTION

HER2/neu is a protooncogene often amplified and overexpressed in ovarian and breast cancer cells (Di Fiore et al 1987, Berger et al 1988, Guerin et al 1988, van de Vijver et al 1988, Slamon et al 1989, Nielsen et al 2007). The level of its expression is associated with cancer malignancy (Berchuck et al 1990, King et al 1992, Zagouri et al 2007, Robert & Favret 2007). The ovarian or breast cancer cells may have approximately 3×106 receptors - HER2/neu gene expression products - expressed from multiple copies of the gene, while healthy cells in these organs may have approximately 2×104 HER2/neu receptors on their surfaces. This leads to great increase in stimulations of signal transduction pathways, thus accelerated cell cycles and increased cell proliferation (King et al 1988, Lahusen et al 2007). HER2/neu positive cancers are the most invasive and have the worst prognosis. Therefore, levels of gene expression products and their distribution determined with monoclonal antibodies are of great diagnostic and prognostic value (Harris et al 1989). Furthermore, they are currently the primary target for antibody-guided, receptor-targeted therapies (Hudziak et al 1989, Jorgensen et al 2007, Park et al 2007, Allen et al 2007).

Surgical biopsies are the primary material used currently for diagnostic analysis in immuno- histopathology laboratories (Shin et al 2007, Tischkowitz et al 2007, Tuma 2007, Carney et al 2007). Many techniques dealing with the evaluation of gene expression and its products include real time qualitative PCR, DNA microarray, differential display, blotting, serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE), etc. Each technique relies upon testing ex vivo of a small tissue or cell sample from a particular anatomical location at the time of biopsy only. However, the cancer gene expression profiles change rapidly, so are the levels and distributions of gene expression products (Fink-Retter et al 2007, Moon et al 2007). Diagnosis and prognosis would be far more accurate, if they would be based upon the images of the entire cancer and projections of its kinetics upon the whole patient's pathophysiology.

In vivo molecular imaging of these antibodies would greatly facilitate such a diagnosis as well as reduce the patient's trauma. This could be done with antibody guided contrast in vivo in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI offers not only the best spatial resolution from all in vivo imaging modalities currently available, but also the topographic reference for location of these probes within anatomy of the human body. The antibody guided probes, could provide the information concerned not only with antigenicity per se, but also report quantitative differences in levels of expression, as well as presence of mutations, within architecture of the whole patient's body at once.

The main objective of this work was to develop antibody guided molecular probes suitable for studying functions and locations of the HER2/neu gene expression products in vivo with MRI.

For developing of new probes for in vivo MRI, it is worth to consider that registered contrast differences between various tissue compartments are generated by local differences in relaxivities of water protons between those compartments. These are translated into varying brightness of the image details on the MRI scanner's screen. Therefore, it is not as much the strength of the resonance signal itself, but rather the relative differences in signal intensity between various structures and/or in the signal to noise ratios that are the most essential properties in successful visualization of the analyzed features. Gadolinium (Gd), Europium (Eu), or Iron (Fe) atoms affect water proton relaxivities in their very immediate vicinities. 10-5 M of Gd is considered to be concentration threshold for inducing such a change in relaxivity of water, that it will be detected in MRI in vivo. If chelated into antibodies, these atoms indirectly report the presence of molecules that were targeted by these antibodies. Attempts to realize that idea were conveyed by randomly attaching reporters: Gd chelates, dendrimers, or Fe nanoparticles to monoclonal IgG antibodies, thereby introducing paramagnetic properties (Curtet et al 1985, Mendonca et al 1986, Linger et al 1986, Weissleder 1991, Unger et al 1999, Kobayashi et al 2003). Two main factors contributed to explanations why these attempts did not succeed. Random incorporation of reporters into IgG molecules led to compromised specificity of those antibodies, thus low specific binding signal and high background due to non-specific binding. Significant increase in size of antibodies due to incorporation of reporters and change of their properties led to steric hindrance and repulsion forces. I have promoted an entirely different approach to improving labeling effectiveness by genetic engineering heterospecific, poly-functional molecules (Malecki et al 2002). They were engineered to contain multiple, highly specific, separate domains assigned to their functions: scFv guided targeting domain, metal atoms chelating domains, signaling sequences, etc. Upon incorporation of Gd or Eu these molecules were gaining superparamagnetic properties without affecting their targeting functions.

The main hypothesis of this project was, that proportional increase in the number of HER2/neu receptors per one cell would result in the proportional increase in Gd atoms anchored via scFv to this cell, and that would result in a proportional increase in relaxivity of the surrounding water; thus leading to the proportional increase in the signal strength recorded with NMR of ex vivo samples or MRI in vivo.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Cell cultures

The cell lines TOV-112D CRL-11731 and CRL-11732 OV-90 were derived from primary malignant adenocarcinomas of the ovary at grade 3, stage IIIC. They were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of MCDB 105 medium and Medium 199, 85%; donor bovine serum 15% (ATCC). The cells were tumorigenic in nude mice. Cultured in soft agar they formed colonies and spheroids. The cells tested positive for HER2/neu and p53 mutation. The cell line NIH OVCAR3 HTB-161 was derived from the cells in ascites of a patient with malignant adenocarcinoma of the ovary. The cell line was grown in RPMI-1640 Medium (ATCC) supplemented with 0.01 mg/ml bovine insulin and donor bovine serum to a final concentration of 20%. These cells were positive for estrogen and progesterone receptor. They formed tumors in nude mice. They formed colonies and spheroids grown in soft agars. The cell line CRL-2340 HCC2157 was derived from the ductal carcinoma of the mammary gland tumor classified as TNM stage IIIA, grade 2, with lymph node metastasis. The cells were grown in a 1:1 mixture of Ham's F12 medium with 2.5 mM L-glutamine and Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium adjusted to contain 1.2 g/L sodium bicarbonate with additional supplements (ATCC). The cell line MCF7 HTB-22. The cells were positive for estrogen receptor and expressed WNT7B oncogene. The medium to culture this cell line was Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium (ATCC) with added following components: 0.01 mg/ml bovine insulin; donorl bovine serum to a final concentration of 10%. The cell line 184A1 CRL-8798 was originally established from normal mammary tissue and transformed with benzopyrene. The line appeared to be immortal, but not malignant. The line was grown in Mammary Epithelial Growth Medium (MEGM) (Clonetics) supplemented with 0.005 mg/ml transferrin and 1 ng/ml cholera toxin. The normal, adherent fibroblast cell line Detroit 573 CCL-117 was derived from skin. It was grown in Minimum essential medium (Eagle) in Earle's BSS with non-essential amino acids (ATCC), sodium pyruvate (1 mM) and lactalbumin hydrolysate (0.1%), 90%; fetal bovine serum, 10%. The cells were grown into spheroids within synthetic extracellular matrix.

Superparamagnetic single chain variable fragment (scFv) antibodies

Plasmid constructs were described in the details (Malecki et al. 2002). Coding sequences for variable fragment antibodies (scFvs) targeting HER2/neu selected from the surface displayed libraries were cloned in pM vectors designed with CMV immediate early promoter, SV40 poly(A) termination, hexahistidine, pentaglutamate, and selection neomycin-resistance coding sequences. Constructs for these scFv antibodies were electroporated into human myelomas (Malecki 1996; Malecki et al. 2002). Expressions of these constructs resulted in secretion of hetero-specific, poly-functional, mono-valent scFv antibodies. Chelating sites were saturated with metal ions: Gd, Eu, Tb. Purification from non-bound metal was performed on affinity columns. The antibodies were produced in modified roller bottles.

Freezing and freeze-substitution of cell spheroids

The details of the cryoimmobilization by freezing were described previously and are only briefly presented here (Malecki 1996). The cells injected into the chambers were rapidly frozen in nitrogen slurry down to down to -196°C. The frozen samples were plunged into methanol precooled to -90°C in the freezer (ThermoNoran). Temperatures were maintained at -90°C, -35°C, and 0°C for 48 hour. Infiltration with Lowicryl preceded polymerization with UV at -35°C and ultramicrotomy. Alternatively, critical point drying was followed by fast atom beam sputter coating.

Immunolabeling

Cell spheroids grown in culture were spun down at 300×g. The cells were resuspended in donor serum to which superparamagentic antibodies were added. Upon completion of labeling the cells were rinsed with PBS. They were studied with NMR or processed by freezing in preparation for LSCM or EDXSI. Alternatively, cell lysates electrotransferred onto PVDF membranes were immunolabeled with the scFv antibodies with or without chelated Gd, Eu, Tb atoms.

Determination of metal atoms incorporated into chelating sites

The number of atoms chelated into the metal binding domains of the scFv was determined by using a titration method based on a competition between GdCI3 and radioactive, carrier-free 153 GdCI3. Several aliquots of antibodies (25 ul) were incubated for 30 min with 100 ul of GdCI3 at various concentrations. The same aliquots were incubated for 30 min with 100 uCi of 153 GdCI3. Free Gd ions were complexed with 10 ul of 0.1 M DTPA. An aliquot of each solution was chromatographed on a silica ITLC (Gelman) support, using 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 5, as an eluent. Alternatively, the chelated sites were saturated with Gd. Subsequently, these samples were purified on the gels as outlined above. Finally, they were analyzed with electron energy loss spectral imaging or EDX to determine total C to Gd ratio or in other words, the number of Gd atoms per scFv molecule. Alternatively, the scFvs were altered through carboxyl terminal derivatization with 125 I and their chelated sites saturated with 153 Gd. Subsequently, these samples were purified on the gels as outlined above. They were analyzed on a multi-channel analyzer, which can display live full-energy spectrum 125 I at energy of 35 keV and 153 Gd at energy of 99 keV; thus it was able to distinguish these two isotopes (Packard Cobra Gamma Counter).

Native electrophoresis

2% agarose gel was poured using a 10 mM Tris, 31 mM NaCl buffer of varying pH, that did not contain any denaturing agents. The samples in their native state were loaded after mixing with glycerol to add density without denaturing the proteins. The gel was run in the same buffer used for pouring the agarose at 60 mAmps until the desired separation was reached. The gel was then stained for 30 minutes in Sypro Tangerine Gel Stain (Invitrogen) diluted in the running buffer before imaging using a FluorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

SDS-PAGE

Electrophoresis was run on 12% polyacrylamide gel. 0.75 thick combs with the 2mm lanes allowed loading standard, cell culture lysates. The samples, after mixing with SDS and DTT containing sample buffers (Sigma) were loaded into the wells. The gels were run using a Tris/Glycine/SDS/DTT running buffers. After the run, the gels were stained with colloidal silver or Sypro Tangerine for imaging using a FluorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Electrotransfer

After electrophoresis, the samples were immediately transferred onto PVDF. Immunoblotting was performed with the Mini Trans-Blot Cell (Bio-Rad) within CAPS: 10 mM 3-[Cyclohexylamino]-1-propanesulfonic acid (CAPS), Tris/glycine transfer buffer 25 mM Tris base, 192 mM glycine, pH 8.3. Prior the transfer the cooling units were stored with deionized water at 0°C. Immediately after electrophoresis the gel, membrane, filter papers and fiber pads were soaked in transfer buffer for 5-10 min. The pre-cooled transfer units were filled with cooled transfer buffer and electrotransfer proceeded at 350 mA.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy

The three-dimensional stacks of the cells labeled with scFv against HER2/ neu were imaged with the laser scanning confocal system - Odyssey on the inverted microscope – Olympus. Excitation wavelengths were used: 337, 488, 543, and 588nm. Images were acquired with Kernel filtration and deconvolution of the data followed by 3D or album display for analysis.

Nuclear magnetic resonance

The wide-bore nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer operated at 9T (Brucker) with a cage resonator was used to evaluate relative relaxivity of the samples based upon T1 measurements. T1 spin lattice relaxation times were calculated and using inversion recovery pulse sequence were measured using inversion recovery imaging with Tl= 50-4000 ms in 100 ms increments. T1 was also calculated from T1-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T1-FLAIR) sequence (Tr/Te/Flip = 2210/9.6/90), as well as standard T1-weighted imaging sequences (Tr/Te/Flip = 400/6/90).

Energy dispersive x-ray spectral imaging

Supramolecular analysis of labeling with the scFv against HER2/neu was performed on the Scanning Electron Microscope with Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectral Imaging System (EDXSI) -Hitachi 3400. Complete elemental spectra were acquired for every pixel of the scans to create the elemental databases. From them, after selecting an element specific energy window, the map of this element atoms’ distribution was calculated with ZAF correction (NIST). As the antibodies were tagged with atoms of Gd, Eu, etc - exogenous elements incorporated into their structure, so was the location of antibodies determined based upon the elemental maps (Malecki 1996, Malecki et al 2002).

RESULTS

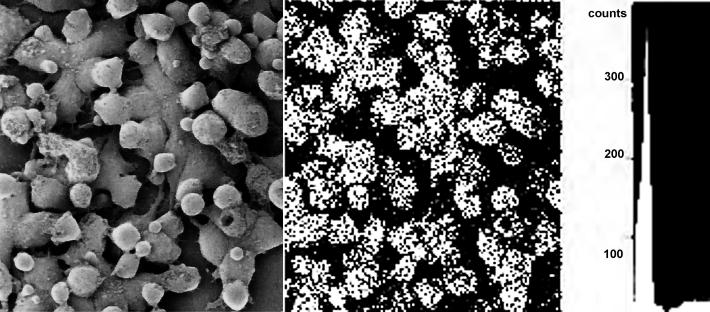

The major problem with designing new contrast agents for molecular imaging was lack of methods providing information concerned with their cell surface distribution and subcellular traficking at the supramolecular level. This situation changed since the introduction of the very sensitive methods of their detection in situ with EELSI and EDXSI (Malecki 1996, Malecki et al 2002). There, genetically engineered antibodies tagged with atoms of selected exogenous elements were localized within the three-dimensional architecture of cells and cell organelles to determine molecular mechanisms governing their bio-distribution and bio-compatibility. In this study, TOV-112D CRL-11731, OV-90 CRL-11732, CRL-2340 HCC2157, NIH OVCAR-3 HTB-161, MCF7 HTB-22, 184A1 CRL-8798, Detroit 573 CCL-117 cell spheroids were cultured and labeled with the anti-HER2/neu superparamagnetic scFv antibodies. These cultured cells were labeled with antibodies chelating Gd or Eu atoms. They were rapidly frozen. Frozen cells were freeze-substituted with no metal incorporation, infiltrated, and embedded. Distributions of antibodies, harboring metal atoms, in ultrathin sections or cell whole mounts were examined with elemental mapping systems. The antibodies chelating Gd atoms were anchored to the cell surface receptors. Therefore, they were visualized by mapping Gd (Figure 1). That could be only possible due to acquisition of the full spectrum for every pixel of the scan to create the elemental data base. Thereafter, an energy window selected for Gd allowed for extracting element distribution within the entire image to create element distribution map. This elemental map based antibody distribution was projected onto the cell surface ultrastructure to determine localization of superparamagnetic antibodies at the molecular level.

Figure 1.

The ovarian cancer cells TOV-112D CRL-11731 labeled with superparamagnetic scFv against HER2 harboring Gd atoms and imaged in Hitachi 3400 SEM with EDXSI. Secondary electron emission shows the cell surface ultrastructure (left). X-ray radiation at the specific for Gd atoms energy determines presence of scFv antibodies (middle). Gated elemental spectrum for Gd extracted from a pixel acquired with the beam parked over the scFv antibody chelated with Gd. Horizontal field width 65 microns.

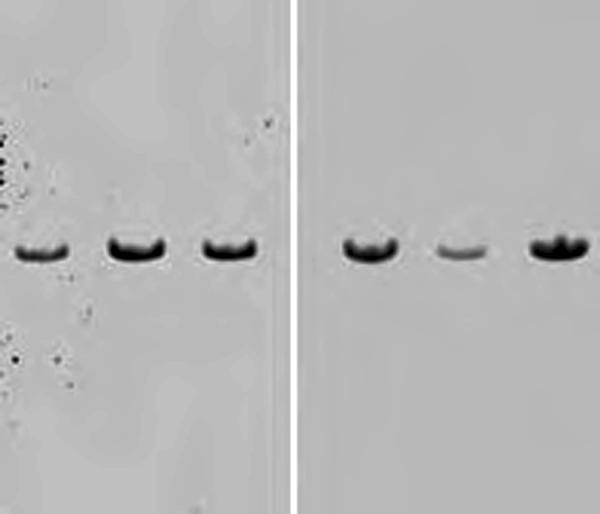

High specificity of superparamagnetic antibodies was also confirmed on Western blots from cell lysates. Exquisite single bands were clear indications of high specificity of the engineered antibodies (Figure 2). All the combinations resulted in the same labeling patterns. Importantly, the blots demonstrated that no other proteins in the entire cell lysate were labeled with our Gd chelated scFv antibodies. The antibodies retained specificity towards targeted receptors, even after Gd coordination. Moreover, the background was entirely label free.

Figure 2.

Immunoblot of the ovarian cancer cells TOV- 112D CRL-11731 and CRL-11732 OV-90 (lanes 1-2) and breast cancer cells CRL-2340 HCC2157 (lane 3) lysates were electrotransfered onto PVDF membrane and labeled with the anti HER2/neu scFv without (left) and with (right) chelating Gd or Eu atoms. Intentionally the space below and above the bands are not cut to show absence of any non-specific binding, but only specific bands are present. Chelation did not change the specificity of scFv antibodies.

The ultimate test for attaining the project's objective was the effect, which superparamagnetic antibodies, anchored to the receptors on cell surfaces, might have on local relaxivity. Table 1 shows the data from one of ten representative experiments. Refined measurements were conducted on wide-bore Bruker (Table 1). Importantly, we observed significant increase in water relaxivity. That resulted in change in relaxivity proportional to the number of the attached Gd chelated scFv antibodies. Relaxivity of water protons was about 200 mM-1 s-1 at 9.4T. The high relaxivity has to result in MRI contrast changes at antibody concentrations as little as 0.1 uM, which is sufficient for imaging of receptors in vivo. It was demonstrated that the scFv antibodies with Gd are capable of labeling cells in vitro. In our studies in cell culture, we have observed a significant contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) enhancement due to superparamagnetic antibodies. Therefore, these scFv-based receptor targeting contrast agents created a clinically relevant change in relaxivity detectable in NMR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differences in T1 relaxation times, between unlabeled physiological fluids and tissues versus cells labeled with the scFv superparamagnetic antibodies.

| Water | 3.210+/- 0.031 s | |

| Serum | 2.273+/-0.024 s | |

| Detroit fibroblasts culture | 1.598+/-0.015 s | |

| Ovarian cancer TOV-112D CRL-11731 | 1.303+/-0.011 s | |

| Ovarian cancer TOV-112D CRL-11731 + anti HER2 scFvGd | 393.626+/-0.028 ms | |

| Breast cancer CRL-2340 HCC2157 | 1.219+/-0.013 s | |

| Breast cancer CRL-2340 HCC2157 + anti HER2 scFvGd | 428.327+/-0.039 ms |

Measurements of T1 relaxation times change induced by GE paramagnetic antibodies in [s] by inversion recovery with 400MHz at 9.4T on 28mm wide-bore Bruker (p < 0.05).

To summarize, in this initial study, striking differences were noticed in the signal strength generated between unlabeled ECM, fibroblasts, ovarian and breast cancer cells after labeling with the scFv antibody chelating Gd – antibody guided contrast agent.

DISCUSSION

This work provides the proof of concept for using superparamagnetic antibodies in detecting differences in levels of gene expression products in cells in vitro and in vivo. Herein labeling of cell receptors with the scFv antibodies resulted in a dramatic shortening of T1. It was proportional to the number of Gd atoms harbored by the scFv antibodies and anchored to the cell surface receptors. The significant difference between the number of the receptors on surfaces of cancer and normal cells translated into the significant difference in the signal intensity between these cells. This work opened new avenues for in vivo studies involving antibody guided contrast.

Success of this work can be primarily attributed to the high specificity, affinity, and small size of the engineered scFv. Their high specificity resulted not only in heavy labeling of the HER2/neu receptors, but also in reduced non-specific labeling of other cells. Therefore, the signal-to-noise ratio was remarkably high. The high affinity of these antibodies was shifting the dynamic on/off balance; thus enhancing conditions for T1 acquisition. Finally, the small size of these scFv antibodies helped in their penetration into the depth of the cell spheroid cultures, as well as, in their packing onto the receptors. That increase in packing or labeling density was also seen on the images from Phosphorimager, LSCM, and EDXSI. The labeling density was much higher with scFv, than it was with Fab or IgG. In this study, it translated into the significant concentration of Gd atoms on surfaces of the cells. Higher number of antibodies, each harboring Gd atoms, resulted in significant changes of the relaxivity reflected in shortening of T1 and strengthening of the generated signal. This would be perceived as the bright spots on the screen of MRI scanners.

Specific signal-to-background-noise ratio is the main factor to discriminate, the structure, which is labeled with the element tagged recombinant scFv antibody guided contrast agent, from the unlabeled structures surrounding it. Therefore, the primary objective of this effort was to bioengineer antibodies in such a way that they would generate label-free background i.e., no non-specific labeling. As described earlier and applied here, it has been accomplished by selecting clones using short receptor domain sequence libraries, purification prior to and after derivatization, evaluation of antibody affinity on native electrophoresis and blue blots, and validation of the data with EDXSI. This complex approach resulted in very specific localization of the superparamagnetic antibodies on targeted HER2/neu receptors.

Improved packing of Gd atoms into chelating domains may enhance local relaxivity of water. Here, it has been accomplished by engineering metal binding domains into the scFv antibodies. Contrary to all of the other methods of antibody derivatization based upon random incorporation of chelating agents, which are changing properties of these antibodies, in this work the highly specific domains are specific and integral parts of superparamagnetic scFv antibodies, but completely separate from antigen binding domains. Therefore, they retain their bio-kinetic properties and antibody binding properties after incorporation Gd. Further, affinity purification, which follows derivatization, secures elimination of all molecules, which might have altered properties.

Above all, the main challenge, before engineering superparamagnetic antibodies for in vivo MRI, is to secure thermodynamic stability of Gd within chelating pockets. Harboring these metals within antibodies has to be extremely stable, so that release and/or transmetallation do not induce toxic effects.

I demonstrate a proof of concept for using the scFv antibody guided contrast agents for evaluating gene expression products. They warrant pursuing studies involving superparamagnetic antibodies in vitro and in vivo. The conclusions outlined above should serve as guides for their streamlining into in vivo molecular imaging endeavors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr Malecki acknowledges with thanks the generous support received from the National Science Foundation as the grants 9120056, 9522771, 9902020, and 0094016, from the National Institutes of Health as the National Biotechnology Resource Grant, the South Dakota Research Foundation, and from South Dakota Governor Michael Rounds as 2010 Seed Award. He also thanks Sarah Nagel and Chaitanya Dodivenaka for technical assistance. Dr. Malecki also thanks Dr. J. Markley and Dr. M. Anderson of NMRFAM for access to the instrumentation at the National Facility.

LITERATURE CITED

- Allen SD, Garrett JT, Rawale SV, Jones AL, Phillips G, Forni G, Morris JC, Oshima RG, Kaumaya PT. Peptide vaccines of the HER-2/neu dimerization loop are effective in inhibiting mammary tumor growth in vivo. J Immunol. 2007 Jul 1;179(1):472–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchuck A, Kamel A, Whitaker R, Kerns B, Olt G, Kinney R, Soper JT, Dodge R, Clarke-Pearson DL, Marks P, et al. Overexpression of HER-2/neu is associated with poor survival in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1990 Jul 1;50(13):4087–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger MS, Locher GW, Saurer S, Gullick WJ, Waterfield MD, Groner B, Hynes NE. Correlation of c-erbB-2 gene amplification and protein expression in human breast carcinoma with nodal status and nuclear grading. Cancer Res. 1988 Mar 1;48(5):1238–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney WP, Leitzel K, Ali S, Neumann R, Lipton A. HER-2/neu diagnostics in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(3):207. doi: 10.1186/bcr1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtet C, Tellier C, Bohy J, Conti ML, Saccavini JC, Thedrez P, Douillard JY, Chatal JF, Koprowski H. Selective modification of NMR relaxation time in human colorectal carcinoma by using gadolinium-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid conjugated with monoclonal antibody 19-9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(12):4277–4281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fiore PP, Pierce JH, Kraus MH, Segatto O, King CR, Aaronson SA. erbB-2 is a potent oncogene when overexpressed in NIH/3T3 cells. Science. Jul 10. 1987;237(4811):178–82. doi: 10.1126/science.2885917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink-Retter A, Gschwantler-Kaulich D, Hudelist G, Mueller R, Kubista E, Czerwenka K, Singer CF. Differential spatial expression and activation pattern of EGFR and HER2 in human breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007 Aug;18(2):299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin M, Barrois M, Terrier MJ, Spielmann M, Riou G. Overexpression of either c-myc or c-erbB-2/neu proto-oncogenes in human breast carcinomas: correlation with poor prognosis. Oncogene Res. 1988;3(1):21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fiore PP, Pierce JH, Kraus MH, Segatto O, King CR, Aaronson SA. erbB-2 is a potent oncogene when overexpressed in NIH/3T3 cells. Science. 1987 Jul 10;237(4811):178–82. doi: 10.1126/science.2885917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AL, Nicholson S, Sainsbury JR, Farndon J, Wright C. Epidermal growth factor receptors in breast cancer: association with early relapse and death, poor response to hormones and interactions with neu. J Steroid Biochem. 1989;34(1-6):123–31. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudziak RM, Lewis GD, Winget M, Fendly BM, Shepard HM, Ullrich A. p185HER2 monoclonal antibody has antiproliferative effects in vitro and sensitizes human breast tumor cells to tumor necrosis factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Mar;9(3):1165–72. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen JT, Nielsen KV, Ejlertsen B. Pharmacodiagnostics and targeted therapies - a rational approach for individualizing medical anticancer therapy in breast cancer. Oncologist. 2007 Apr;12(4):397–405. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-4-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BL, Carter D, Foellmer HG, Kacinski BM. Neu proto-oncogene amplification and expression in ovarian adenocarcinoma cell lines. Am J Pathol. 1992 Jan;140(1):23–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CR, Borrello I, Bellot F, Comoglio P, Schlessinger J. Egf binding to its receptor triggers a rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of the erbB-2 protein in the mammary tumor cell line SK-BR-3. EMBO J. 1988 Jun;7(6):1647–51. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Kawamoto S, Jo SK, Bryant HL, Jr, Brechbiel MW, Star RA. Macromolecular MRI contrast agents with small dendrimers: pharmacokinetic differences between sizes and cores. Bioconjug Chem. 2003;14(2):388–394. doi: 10.1021/bc025633c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahusen T, Fereshteh M, Oh A, Wellstein A, Riegel AT. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine phosphorylation and signaling controlled by a nuclear receptor coactivator, amplified in breast cancer 1. Cancer Res. 2007 Aug 1;67(15):7256–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linger EC, Totty WG, Neufeld DM, Otsuka FL, Murphy WA, Welch MS, Connett JM, Philpott GW. Magnetic resonance imaging using gadolinium labeled monoclonal antibody. Invest Radiol. 1985;20(7):693–700. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198510000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki M. Preparation of plasmid DNA in transfection complexes for fluorescence and electron spectroscopic imaging. In: Malecki M, Roomans G, editors. Science of Specimen Preparation for Microscopy and Microanalysis. Vol. 10. SMI Press; O'Hare: 1996. pp. 1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki M, Hsu A, Truong L, Sanchez S. Molecular immunolabeling with recombinant single-chain variable fragment (scFv) antibodies designed with metal-binding domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(1):213–218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261567298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendonca Dias MH, Lauterbur PC. Ferromagnetic particles as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging of liver and spleen. Magn Reson Med. 1986;3(2):328–330. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910030218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon YW, Jeung HC, Rha SY, Choi YH, Yang WI, Chung HC. Different criteria for HER2 positivity by IHC can be applied in post-chemotherapy specimens in determining HER2 as a prognosticator in locally advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007 Jul;104(1):31–7. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen KV, Jorgensen JT, Schonau A, Oster A. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007 Sep;131(9):1330. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-1330a-HEGFRT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JW, Melisko ME, Esserman LJ, Jones LA, Wollan JB, Sims R. Treatment with autologous antigen-presenting cells activated with the HER-2 based antigen Lapuleucel-T: results of a phase I study in immunologic and clinical activity in HER-2 overexpressing breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Aug 20;25(24):3680–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert NJ, Favret AM. HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2007 Apr;21(2):293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SJ, Chen B, Hyjek E, Vazquez M. Immunocytochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization in HER-2/neu status in cell block preparations. Acta Cytol. 2007 Jul-Aug;51(4):552–7. doi: 10.1159/000325793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, Holt JA, Wong SG, Keith DE, Levin WJ, Stuart SG, Udove J, Ullrich A. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989 May 12;244(4905):707–712. doi: 10.1126/science.2470152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischkowitz M, Brunet JS, Begin LR, Huntsman DG, Cheang MC, Akslen LA, Nielsen TO, Foulkes WD. Use of immunohistochemical markers can refine prognosis in triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2007 Jul 24;7:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuma RS. Inconsistency of HER2 test raises questions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007 Jul 18;99(14):1064–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger EC, Shen D, Wu G, Stewart L, Matsunaga TO, Trouard TP. Gadolinium-containing copolymeric chelates-a new potential MR contrast agent. MAGMA. 1999;8(3):154–162. doi: 10.1007/BF02594593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver MJ, Peterse JL, Mooi WJ, Wisman P, Lomans J, Dalesio O, Nusse R. Neu-protein overexpression in breast cancer. Association with comedo-type ductal carcinoma in situ and limited prognostic value in stage II breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1988 Nov 10;319(19):1239–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811103191902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissleder R. Target-specific superparamagnetic MR contrast agents. Magn Reson Med. 1991;22(2):209–212. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910220209. discussion 213-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Zografos GC. Precursors and preinvasive lesions of the breast: the role of molecular prognostic markers in the diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. World J Surg Oncol. 2007 May 31;5:57. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]